Pages 22-51

Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

CHAPTER I. West of Farringdon Road

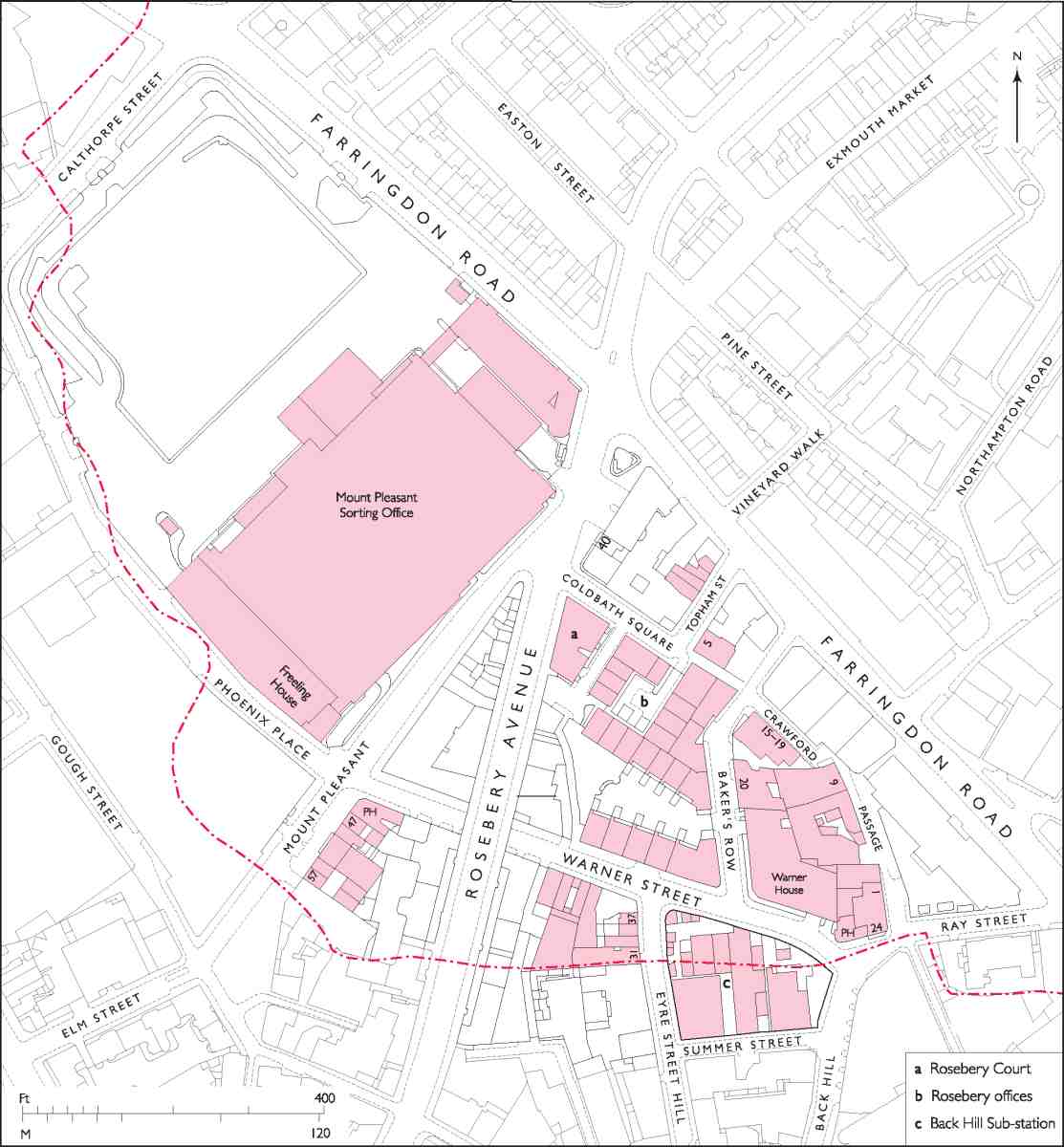

6. Mount Pleasant and Rosebery Avenue area. Broken red line shows former Clerkenwell parish boundary

The area described in this chapter lies at the western edge of Clerkenwell, merging indistinctly to the south and west with Holborn and St Pancras. The old parish and modern borough boundaries here follow essentially the line of the Fleet river, a rough arc sweeping from Farringdon Road north of Calthorpe Street and back to Farringdon Road south of Ray Street (Ill. 6). This small district was formerly known as Cold Bath or Coldbath Fields, and (together with some acres adjoining in the Gray's Inn Road area of Holborn) was a single landholding until the 1780s, successively the Baynes-Warner and Jervoise estate, when the north-eastern half was sold for a new county prison; the remainder was broken up in 1811.

Today, Coldbath Fields has long since lost not only its name but, through redevelopment and road improvements, any sense of separate identity or special character. Both were once quite marked. Then on the outskirts of the metropolis, the south-eastern part of the estate was developed from 1719 with terraces of small and middlingsized houses centred on the Cold Bath, a privately run hydropathic establishment opened in the late 1690s. Part residential suburb, part spa, part place of recreation and amusement with many hostelries, the new neighbourhood was before very long almost engulfed by less agreeable developments. On the north-western ground, now largely occupied by Mount Pleasant Sorting Office, a distillery was built in the 1730s, and a smallpox hospital in the 1750s. These were joined towards the end of the eighteenth century by the prison, the Middlesex House of Correction, which became notorious for the brutality of its regime. South of the Cold Bath, near the old and insalubrious quarter called Hockley-in-the-Hole, the parish workhouse, built in the 1720s, was greatly enlarged in 1790.

Prison, workhouse, hospital and distillery had all gone by the end of the nineteenth century, along with the Cold Bath itself, but the locality did not recover anything like its old character. The creation of Farringdon Road in the 1860s and 70s, and Rosebery Avenue in the 80s and 90s, involved a great deal of reconstruction, most of it on a far bigger scale than hitherto, with blocks of industrial dwellings much in evidence. By the time Rosebery Avenue was built, the houses once inhabited by prosperous bourgeois had long been taken over as workshops and warehouses, or had sunk to low-class lodgings. By the turn of the twentieth century, too, the area was becoming almost wholly absorbed into the immigrant quarter spreading north from Holborn and Saffron Hill known as 'Little Italy'.

There are two major excisions from the account given here: Rosebery Avenue itself, which is dealt with in Chapter IV, and the present-day buildings on the west side of Farringdon Road between Ray Street and Rosebery Avenue, described above with the rest of Farringdon Road in volume xlvi of the Survey of London.

Coldbath Fields: the Baynes—Warner or Jervoise estate

The name Coldbath Fields was applied in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to the area of some eighteen acres between the Fleet (or Turnmill Brook), where the Clerkenwell parish boundary ran, and the high road to St Pancras north of Ray Street. (fn. 1) This land, formerly known in whole or part as Windmill Hill, belonged until the dissolution of the monasteries to St Mary's nunnery, whose precinct lay on the east side of the high road. It was acquired in 1600 by Robert Harvey of Bedfordshire, with other land in Clerkenwell or Islington, from one Nicholas Bagley. (fn. 2) In 1692 the greater part of the estate was let on a 99-year lease by a later Robert Harvey to John Henley of Lambeth, a merchant taylor, three-quarters of his interest being as trustee for Walter Baynes, lawyer, of the Middle Temple. Three and a half years later Harvey sold the freehold of the entire estate in equal shares to Henley and Baynes for £1,650. (fn. 3)

At the time of the sale, the land was mostly taken up by two fields of pasture: Gardiner's Field to the north and the larger Sir John Oldcastle's Field to the south. There was a cluster of buildings and a large rubbish dump or laystall in the south-eastern corner, in the area of Hockleyin-the-Hole. Chief of these buildings was the Cock inn, the forerunner of the present-day Coach and Horses in Ray Street. Another inn, Sir John Oldcastle's, stood some way north of Hockley-in-the-Hole, fronting the St Pancras road at the boundary between the two fields: the site is now occupied by the post office at the southeast corner of the Mount Pleasant postal depot. At the north end of Gardiner's Field was a spot known as Black Mary's Hole or Well, according to one account named after a black woman, Mary Woolaston, who had rented a spring there from the Harvey family and made a living selling the water. About 1697 Baynes created a new conduit or reservoir at Black Mary's Hole for public use, at the same time exploiting another spring a little south of Sir John Oldcastle's to supply a more ambitious commercial venture of his own: the eponymous Cold Bath. (fn. 4)

Henley and Baynes's intentions in acquiring the property in the first place were presumably directed towards some sort of development, for the 1692 lease provided for the erection of buildings (other than 'common brewhouses'). It also allowed digging for gravel—there were well-established gravel pits on the northern part of the estate near Sir John Oldcastle's and Black Mary's Hole (where in 1673 the pioneer archaeologist John Conyers discovered what were thought to be elephant bones from the imperial Roman army). (fn. 5) However, the only new building erected before the 1720s (by which time Henley had long since disposed of his share of the property) was the Cold Bath itself.

Henley sold his share in 1703 to John Greenwood, mercer, and John Warner, banker and goldsmith, for £2,200. Warner, apparently persuaded by Baynes that the estate would one day become valuable building land, bought out Greenwood, leaving himself and Baynes as joint owners, and at about the same time Baynes and Warner acquired another 4¼ acres of land adjoining to the west, in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn (the Claypitt or Clayfield, later known as the Gray's Inn Lane estate). (fn. 6) Warner died in 1721, soon after the south-eastern part of the estate was laid out for building. His share in the property passed to his son Robert, and subsequently, via Robert's daughter Kitty, to her husband Jervoise Clarke (later Jervoise Clarke Jervoise), of Idsworth Park, Hampshire, and their son Thomas Clarke Jervoise. (fn. 7)

The fact that the freehold was held jointly caused friction. Not only was Baynes of the opinion that he deserved a bigger share of the property, as recompense for his input of money and effort in promoting its development, but he was frustrated by what he saw as Robert Warner's obstruction of further improvement. In 1736, after years of litigation over the proposed division of the estate into two separate freeholds, he sold his share in a number of properties (including Sir John Oldcastle's, the Cobham's Head public house and the workhouse) to Warner for £1,900. But the dispute continued after Baynes's death in 1745, at the age of 91, when the remnant of his share passed to his son Walter. (fn. 8)

Walter Baynes junior called in the 'Skillful and experienced Surveyor' Robert Morris, a man with particular knowledge of London estates, who concluded that it was impossible to split the estate fairly. The chief problem seems to have been the Cold Bath, and the risk of its being damaged by possible interference with the source of the cold spring, or the establishment of a rival bath at Black Mary's Hole. A deal to sell the entire estate and split the proceeds was called off by Warner in 1747. (fn. 9)

Baynes died at Bath in 1775, his share of the estate passing into the hands of trustees to be mortgaged or sold to pay his debts. (fn. 10) Most of the large north-western portion of the estate was sold in 1787 to the Middlesex justices as the site for the new county House of Correction. (fn. 11) The remaining Baynes shares in the Coldbath Fields and Gray's Inn Lane estates were put up for auction in 1787–8, where they were bought by Jervoise Clarke Jervoise for £8,400 and £3,450 respectively. (fn. 12)

With Jervoise's death in 1808, ownership of both shares in the estate passed to Thomas Clarke Jervoise, who died childless the following year leaving the property to the offspring of his brother-in-law, the Rev. Samuel Clarke, who subsequently adopted the surname Jervoise. In 1811 the estate was broken up at auction, realizing £76,970. Any remaining properties were disposed of gradually over the next few years. (fn. 13)

Between Farringdon Road and Mount Pleasant

The small, roughly triangular area between present-day Mount Pleasant and Farringdon Road north of Ray Street comprises the south-eastern half of the former Coldbath Fields. This was where Baynes and Warner's house-building activities began in the early eighteenth century around the Cold Bath, erected some years before (Ill. 7).

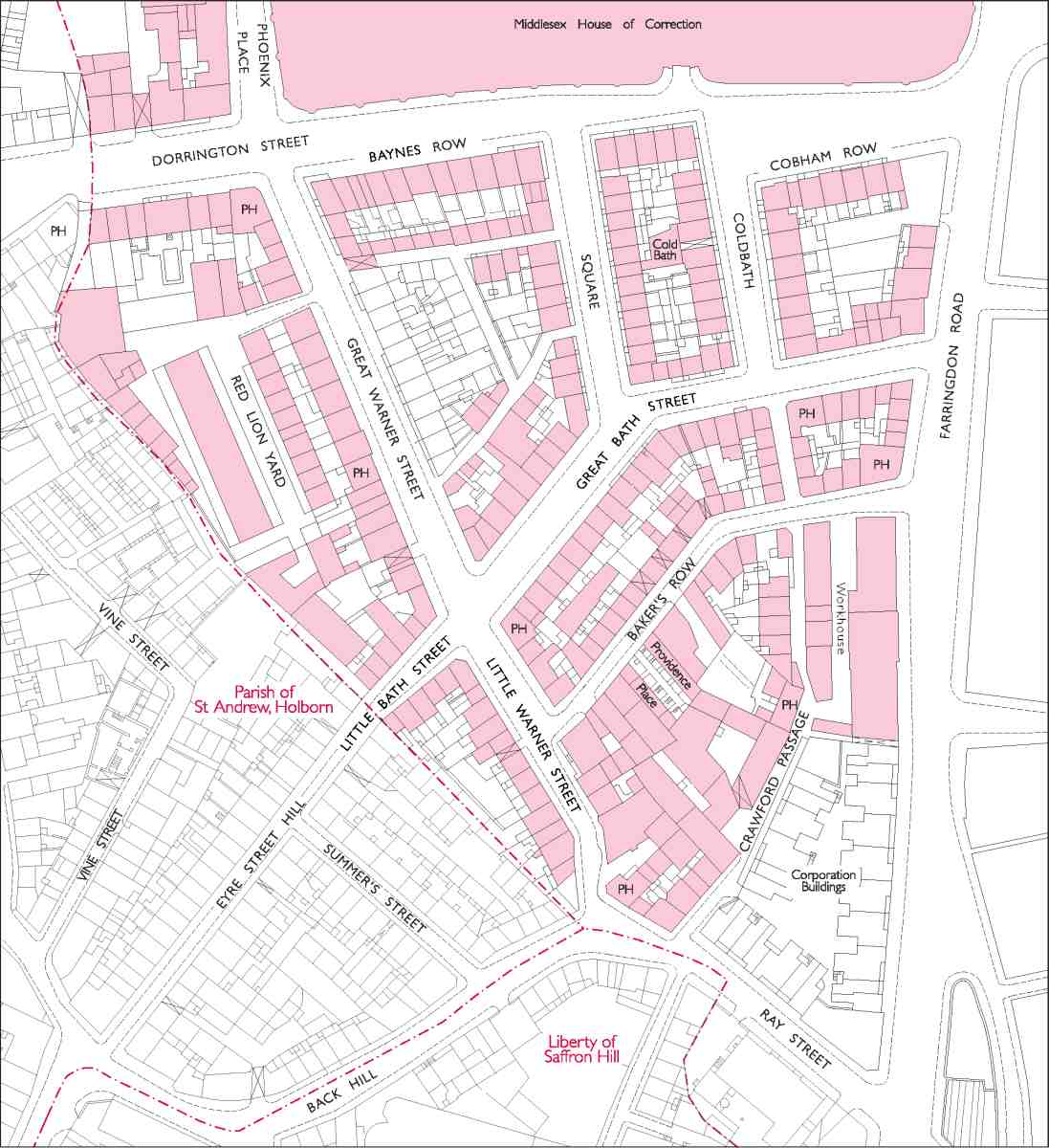

7. The former Baynes-Warner or Jervoise estate, c. 1874

The Cold Bath, 1697–1887

In 1697 Walter Baynes came up with the idea of converting the 'antient Conduit and Spring' near Sir John Oldcastle's, which had run waste for many years, into a cold bath for medical treatment. John Henley, the coowner of the ground, doubted the project was commercially viable and declined to take part, but Baynes went ahead with a small syndicate, including his old friend, John Warner, the goldsmith who subsequently acquired Henley's share in the estate, and John Sly, a haberdasher, (fn. 14) who acted as trustee for the syndicate (and later resided in one of the first houses built in Dorrington Street). It was probably Baynes who recruited a leading medical man in the field of hot and cold bathing, Dr Edward Baynard, of London and Bath, to help promote the bath in return for a share of any profits.

The partners, with a lease from Baynes and Henley, soon replaced the old conduit with a bath and some sort of bath-house at a cost of only £50, but without resident staff and adequate facilities for patients it was not a success. The next year a brick dwelling-house was built at the bath and a resident manager appointed. In the early 1700s, however, with the bath still not paying and the manager wanting more money, Baynes, a practising lawyer, took the step of moving with his family from the Temple to take up residence at the bath-house, which he greatly enlarged with dressing-rooms, a buttery and other accommodation for patients. He put the final cost of the building, including his improvements, at £1,100, of which £150 was paid by Warner. From then until his retirement in the 1730s, Baynes combined his legal work with the duties of Master of the Cold Bath, in which he was assisted by his wife. Henry Million, his legal clerk, was also in residence by 1720. (fn. 15) Not surprisingly, the arrangement involved 'great Inconveniency'. Baynes gradually bought out the partners, whose faith in the venture seems never to have been more than tepid, and Baynard too, eventually bringing the loss-making business round. By the late 1740s, after Baynes's death, the bath had become a valuable property bringing in an annual rent of £120. (fn. 16)

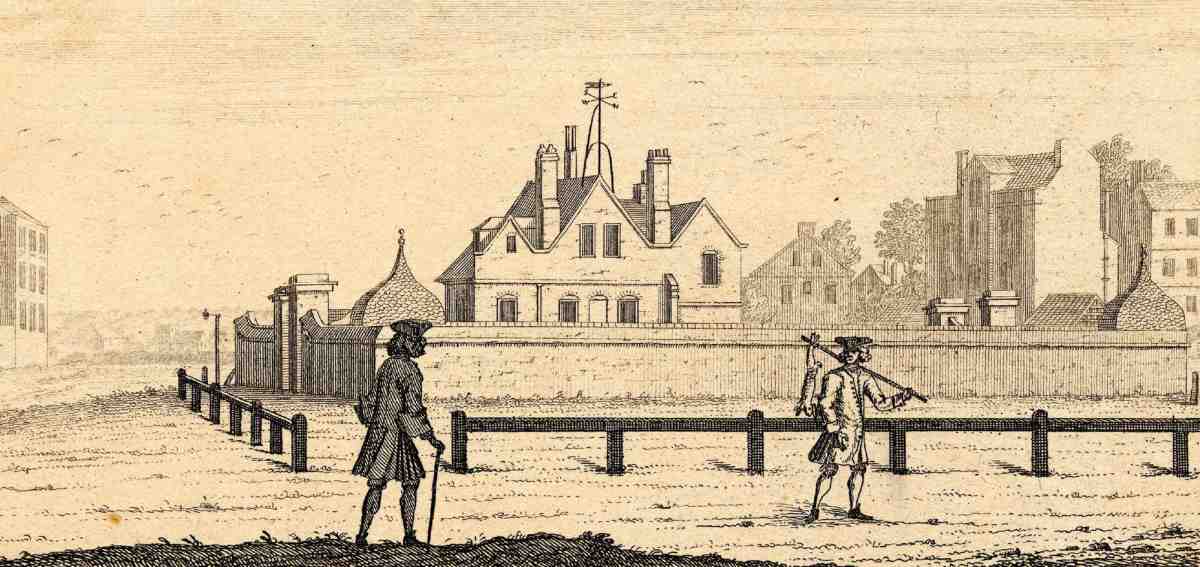

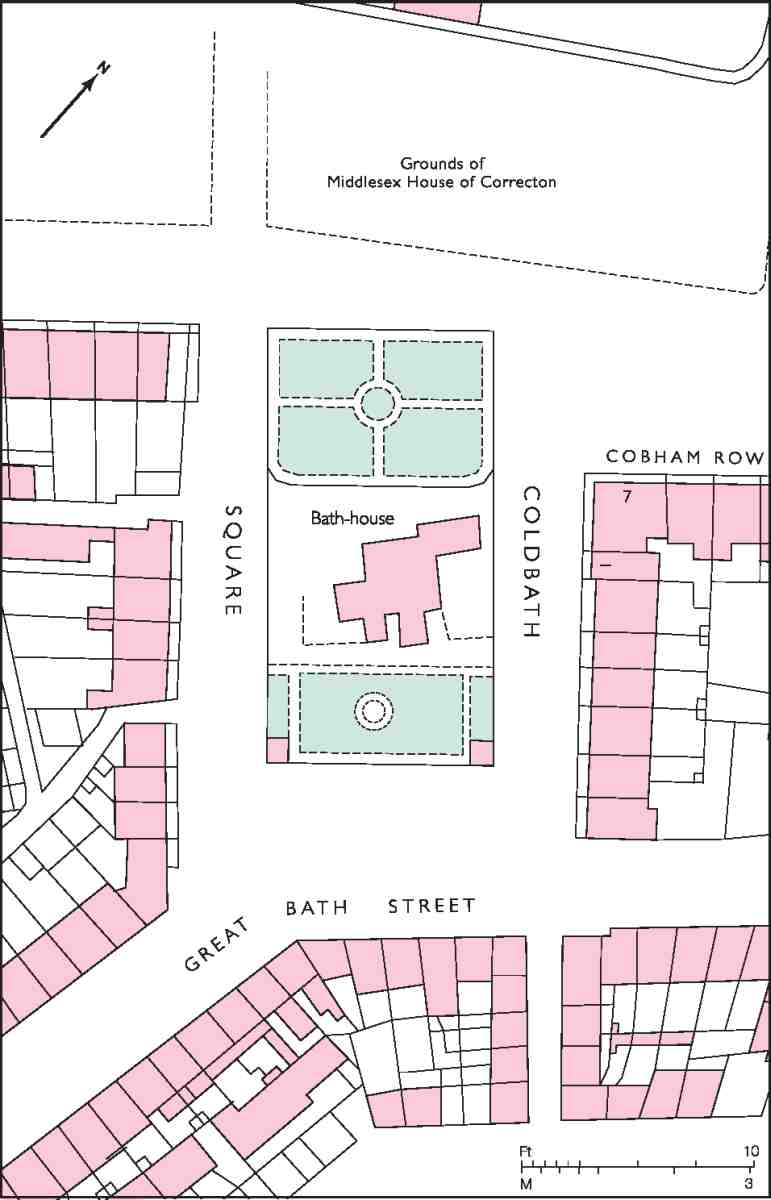

In the early years, the Cold Bath stood in a small paled–in garden, but with the start of building development on the estate in 1719 the garden was enlarged and surrounded with a brick wall, to become the nucleus of Coldbath Square (Ill. 9). (fn. 17) Illustration 8 shows the bath-house after this alteration, with ogee-roofed gazebos at the southern corners of the walled garden. Various further additions appear to have been made to the bath-house in the course of the eighteenth century, producing a rambling, irregular-looking building. Particulars drawn up at the time of the dispersal of the Jervoise estate in 1811 mention a long narrow hall and four rooms on the ground floor, with a 'good' staircase, and five rooms on the first floor. The ancillary accommodation included two kitchens, a pantry, arched wine-cellars, three dressing-rooms and a pump room. The bath itself was a 'spacious' pool constructed in marble, and filled to a depth of 4 ft 7 ins by the spring, which was said to supply 20,000 gallons of water daily, 'strongly impregnated with Steel and Sea Salt'. A Victorian illustration shows the bath, possibly in its original form, with steps in one corner, galleries on two or three sides, and water gushing in from an ornamental spout (Ill. 10). (fn. 18)

8. The Cold Bath seen from the south, 1731

9. The Cold Bath, Coldbath Square, c. 1808

Baynes's house seems to have survived essentially intact until 1814, after its acquisition by the London Fever Hospital (explained below), when the building was partly demolished. It is not clear whether the house was rebuilt or only altered when the Cold Bath was subsequently cloaked in by new houses, in 1818–19. Additional baths were probably constructed at this time: Thomas Cromwell, in the 1820s, wrote of facilities for showers and warm baths besides cold. (fn. 19)

One of a number of baths and spas opened in England in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the Cold Bath was more specifically a medical establishment than some of the London bagnios—often doubling as brothels—which included cold plunges among their attractions. As the 'most noted and first about London', Baynes's bath played a significant part in what was seen at the time as the 'revival' of cold bathing as a treatment for illnesses and infirmities, a practice (with Classical antecedents) which had apparently fallen into decline with the Reformation and the closure or abandonment of many ancient holy wells. Baynes's own interest in the subject may have stemmed from his origins in the north country—he was the son of a gentleman of Laingley, Yorkshire—where the cold-bathing tradition had remained alive. St Mungo's Well, one of the most famous cold baths in England, was situated near Harrogate, and in Harrogate itself a cold bath was promoted by Dr John Neale, son of George Neale who was instrumental in developing Harrogate spa in the later seventeenth century. (fn. 20)

The Cold Bath at Clerkenwell, celebrated in verse by

Sir Richard Steele, (fn. 21) was promoted by Baynes as 'the best

remedy' for a preposterously wide range of conditions:

Dissiness, Drowsiness, and heavyness of the head, Lethargies,

Palsies, Convulsions, all Hectical creeping Fevers, heats and

flushings, Inflammations and ebullitions of the blood and

spirits, all vapours, and disorders of the spleen and womb, also

stiffness of the limbs and Rheumatick pains, also shortness of

breath, weakness of the joints, as Rickets, etc., sore eyes,

redness of the face, and all impurities of the skin, also deafness, ruptures, dropsies and jaundice. It both prevents and

cures colds, creates appetites, and helps digestion, and makes

hardy the tenderest constitution. (fn. 22)

Dr Baynard, who evidently recommended it to his clientele, described the regime followed in 1699 by a particular patient, a woman suffering from (inter alia) hysteria and fits: twenty-two visits to the Cold Bath in the space of a month, dipping herself six or seven times every morning, 'without staying in the Water any longer than the time of Immersion'. (fn. 23) Admission to the pool about this time cost 2s, or 2s 6d if the patient required lowering into the water by means of a chair suspended from the ceiling. St Bartholomew's Hospital paid three guineas a year for the use of the bath by its patients, plus a guinea for Baynes's servants. (fn. 24)

The building continued in use for cold and warm baths until its closure in 1886 or 1887, when along with much of Coldbath Square it was pulled down for the construction of Rosebery Avenue. The price of a bath fell to just sixpence, but to the end the essentially medical character of the establishment seems to have been preserved, and the bath was used by patients from the Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest at Brompton, and elsewhere. (fn. 25) In 1885 the proprietor asserted that the cold spring remained in constant use, 'and still retains its medicinal and curative properties'. By this time, however, the name Cold Bath had been superseded by the more enticing 'Nell Gwynne baths', after 'a nude figure, on porcelain', an old if not original decoration at the baths, said to depict Nell Gwyn. (fn. 26)

At the sale of the Jervoise estate in 1811 the Cold Bath, garden and some vacant ground adjoining the southeast end were bought by the Institution for the Cure and Prevention of Contagious Fevers (London Fever Hospital). The institution had been looking for a site in the vicinity of the House of Correction for the past couple of years for a 'House of Recovery' for typhus victims, to replace its existing building in Gray's Inn Lane. (fn. 27) It was thought at first that the bath-house could simply be adapted, but in 1814 (progress having been held up by the protracted completion of the purchase) plans for a new building were drawn up by the surveyors Joseph Wigg and William Brooks. Part of the bath-house was then pulled down to provide materials for enclosing the vacant ground, but enough was left standing 'as is necessary for the use of the Bath, and for the residence of the persons who may inhabit the premises'. (fn. 28)

10. Excerpt from a handbill for the Cold Bath, 1873

The new hospital, on a larger scale than originally envisaged, would have had wards for scarlet fever as well as typhus patients. However, the institution's view that the site was 'peculiarly eligible' on account of its airy situation was not shared by the people of Clerkenwell, who saw risks to health and property values in opening such an establishment in what they saw as a particularly crowded neighbourhood, and the project had to be abandoned. Fortunately the governors of the St Pancras Smallpox Hospital came to the rescue, offering one of their two buildings at Battle Bridge (present-day King's Cross) for the House of Recovery, and this remained the London Fever Hospital for over thirty years. (fn. 29)

Following an unsuccessful attempt to sell the site at auction, in 1818 the Fever Institution let it on lease to a builder, James Pitcher of Upper Thames Street, who erected twenty-eight houses there, numbered in Coldbath Square. (fn. 30) The old bath-house appears to have been altered or rebuilt at this time, Pitcher undertaking to 'complete a Building calculated for the public use of the Cold-bath'. (fn. 31)

In 1887–8, following the clearance of the property by the Metropolitan Board of Works for what was to become Rosebery Avenue, two tenement blocks, Coldbath Buildings, were built on the site of the bath and square by the Artizans', Labourers' & General Dwellings Co. Ltd. Each comprised four floors of dwellings above ground-floor shops and commercial premises. They were designed by the architect F. T. Pilkington, in the style he used for many of the company's developments, with eccentric, outsize detailing in red artificial stone. The buildings, latterly known as Springfield Court, were demolished in 1982 and the site was subsequently redeveloped as part of the 'Rosebery' scheme (see below). (fn. 32)

11. Cobham Row and the east side of Coldbath Square, 1887. The double-fronted corner house is No. 7 Cobham Row; adjoining to the left is No. 6 (the present No. 40 Rosebery Avenue); first Clerkenwell Fire Station (1873) at far left

12. Little Warner Street, east side, looking south towards Ray Street, c. 1875; house at left with quoins and classical doorsurround is No. 6

Building in Coldbath Fields, 1719–c. 1743

The Cold Bath had been established well over twenty years when, in 1719–20, the development of the estate was begun, with the erection of houses in Dorrington Street, now part of Mount Pleasant (see Nos 47–57 Mount Pleasant, below). As with the Cold Bath enterprise, the driving force seems to have been Walter Baynes, and he subsequently laid claim to being the sole 'improver' of the estate, negotiating with builders and others and overseeing the legal side of the development. Among other things, he claimed to have persuaded the inhabitants of the Eyre Street neighbourhood to replace a footbridge over the Fleet at the end of Eyre Street with a brick road-bridge, thus allowing the continuation of Eyre Street northwards over the Cold Bath estate, as Little and Great Bath Streets (Ill. 7). (fn. 33) Warner, however, does not seem to have been entirely supine, erecting one house (the present No. 49 Mount Pleasant) entirely at his own expense, and sharing, presumably with Baynes, the cost of another in order to encourage interest in the estate from builders. With these exceptions, almost the whole of the estate development was carried out on 61-year building leases (Clerkenwell Workhouse, uniquely, was built on a lease for twice the usual term). In order to prevent interference with the Cold Bath spring, leases of the houses near by carried a covenant against digging deeper than three feet. Warner and later his son Robert also helped the development along by lending money to the builders so they could continue working. (fn. 34)

The surveying and setting-out of the ground for building was done by Richard Grimes, a carpenter of St Bartholomew Close (later of Warner Street), (fn. 35) who also helped draw up agreements with builders. For these ser vices he was paid £142. Grimes himself was one of the principal builders on the estate in the 1720s. The street pattern, in particular the lines of Mount Pleasant and Warner Street, seems to have been based to some extent on existing field paths and was presumably partly dictated by the hilly terrain. There was some difficulty in devising a plan to incorporate the Cold Bath, and the solution arrived at involved the expensive work of enlarging and walling-in the garden to make it the centre of the intended 'Cold Bath Square'. (fn. 36)

Following the completion of the Dorrington Street houses, nothing further seems to have been erected until 1724–6, when most of Great and Little Bath Streets, the west side of Baker's Row, the south side of Great and Little Warner Streets, and parts of Baynes Row and Cobham Row (at first called Baynes Street) were built up. (fn. 37) Another lull in the second half of the 1720s was followed by a longer phase of building activity, lasting throughout the 1730s and into the 1740s. (fn. 38) By this time the immediate vicinity of the Cold Bath was covered 'with handsome regular Buildings, and may very well pass for a fine Square'. (fn. 39)

As the qualification in this early description indicates, Coldbath Square was in terms of formal planning a compromise. It was not really a square at all, but rather (in its original form) two unequal rows of houses looking on to the walled garden of the Cold Bath, above which rose the rather eccentric gabled bath-house. Some smaller terracehouses in Great Bath Street took the place of a third side to the square, while the fourth, to the north-west, remained open. The square was not built in one phase. On the south-west side the middle part of the row, erected c.1732, was flanked by houses built c. 1726 as part of the development of Baynes Row and Great Bath Street. The north-east side was mostly of c.1736. The large house at the north end, No. 7 Cobham Row, with a flank front to the square, was built in 1728, and its back yard filled in with another house, later numbered 1 Coldbath Square, about 1789 (Ill. 11). (fn. 40)

Building leases were taken by a fairly large number of builders and allied tradesmen, the most prominent being Richard Baker of St Pancras, carpenter (after whom Baker's Row is named); John Pankeman, bricklayer, who along with Richard Grimes built much of Warner Street; and several members of the Warden family, active principally in and around Bath Street and Bath Row (originally called Warden's Passage). Thomas Dorrington, the City bricklayer who gave his name to Dorrington Street, took leases of a couple of houses only and does not seem to have been involved after the initial phase of building.

The best houses were in the vicinity of the Cold Bath, away from Hockley-in-the-Hole and the workhouse. An exception was the double-fronted house, now demolished, at No. 6 Little Warner Street, on the corner of Baker's Row (Ill. 12). This was erected in 1743, the building lessee, and probably first occupant, being a carpenter, Richard Thomson. (fn. 41)

Stables in Red Lion Yard

In 1725–6 the carpenter Richard Grimes built extensive stables and coach-houses in Red Lion Yard, behind the houses in Dorrington Street and the south side of Warner Street. These were probably substantially the same buildings still standing in the 1860s, when their picturesque appearance and insanitary condition—the upper floors were then in use as family apartments and workshops— caught the attention of The Builder (Ill. 13). However, they may have been altered, even rebuilt, about 1790, when they were let on long lease to two carpenters of Great Warner Street, Robert Gradey and Robert Johnson. (fn. 42) From the description and illustration published in 1865, the stables would appear to have been essentially if not entirely wooden structures, though insurance records describe Grimes's newly finished buildings as half brick, half timber. There were two ranges, one with a very deeply projecting roof, the other with less overhang to the roof and an open gallery along the upper floor. (fn. 43)

13. Stables in Red Lion Yard, 1865. Demolished

Social character and notable residents

Walter Harrison, writing in 1775, found the streets around Coldbath Square 'chiefly inhabited by tradesmen', and this seems to have been the case ever since the houses were first occupied. (fn. 44) Just a couple of titled residents appear in the eighteenth-century ratebooks: Sir Tanfield Lemon, 4th Bart., the son of a London apothecary, who lived in Cobham Row in the 1750s, and Lady Lowther, the widow of Sir Christopher Lowther, 3rd Bart., who lived in Bath Street from the 1730s until her death c. 1753. (fn. 45)

Jane Lewson, who lived on the south-west side of Coldbath Square and died there in 1816 allegedly at the age of 116, was a noted eccentric. She is said to have come there as the young bride of a wealthy merchant, and to have continued living there after being widowed at the age of 26. (This 90-year residence is not supported by the ratebooks, however, which show her at Coldbath Square only from about 1770.) 'Lady Lewson', as she was known, was always dressed in the style fashionable in her youth, and never washed, being convinced of the great risk to health posed by water—living opposite the Cold Bath for so many years this was something she was in a position to judge.

No. 7 Cobham Row, one of the largest houses on the whole estate, was used for several years from 1760 by the Foundling Hospital as its 'Inoculation House' for treating children against smallpox. The existence of the smallpox hospital on the opposite side of the road no doubt suggested this choice of location. In the 1830s the householder was William Pinks, probably the father of William Pinks the Clerkenwell antiquarian, who was born in Great Bath Street in 1829. (fn. 46)

Other residents of note include: the writer Eustace Budgell, a relative and friend of Joseph Addison, at Coldbath Square from 1733 to 1736; Henry Carey, the poet and musician, in Dorrington Street from the 1730s until his suicide in 1743 (though he is traditionally said to have died in Great Warner Street); (fn. 47) Henry Bone RA, enamel painter to George III, at Great Bath Street in 1784; and the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, who died in 1772 at his lodgings in the house of Richard Shearsmith, a perukemaker, at No. 26 Great Bath Street. (fn. 48)

Some impression of the early character of Coldbath Fields can be taken from the prevalence of inns and alehouses there, at least two of them with pleasure grounds for musical concerts, fireworks and other diversions. A few of these inns—Sir John Oldcastle's, the Cock and the Pickled Egg in what is now Crawford Passage—predated the building development under Baynes and Warner. At Sir John Oldcastle's, the 1746 summer season of musical entertainment included—alongside such romantic fare as 'Come Rosalind' and 'Observe the fragrant Blushing Rose'—a new song by John Lockman, set to music by Handel: 'From Scourging Rebellion and baffling proud France', a paean to the Duke of Cumberland. (fn. 49)

Opposite Sir John Oldcastle's was the Cobham's Head at No. 1 Cobham Row, built about 1725. (Oldcastle and Lord Cobham were one and the same man, the Lollard martyr and folk-hero, who according to tradition once lived near by, possibly at the house which later became Sir John Oldcastle's inn). Like the older establishment, the Cobham's Head had a garden at the rear, with gravelled walks, a grove of trees, and in addition a 'fine Canal stock'd with very good Carp and Tench' where guests might fish. Similar musical entertainment to that at Oldcastle's was on offer in the 1740s, including songs from Handel oratorios. An organ was installed in the house in 1744 for musical evenings with firework displays in the garden. (fn. 50) In the 1770s the pub had rooms for billiards and shuffleboard, and several skittle-grounds. (fn. 51)

At Hockley-in-the-Hole, the Cock inn is traditionally said to have had a yard for bear- and bull-baiting, and there was also a cock-pit in Pickled Egg Walk. A sharp distinction must have existed between the rather select attractions in the vicinity of the Cold Bath and the olderestablished, barbaric sports that flourished in this southern area until the middle of the eighteenth century.

Clerkenwell Workhouse

Fourteen years before its closure in 1879 Clerkenwell Workhouse was condemned by the Lancet as one of the two worst poor-law establishments in London, 'fit for nothing but to be destroyed'. It was ill-planned, cramped and poorly ventilated, the foetid air alive with the 'shrieks and laughter of noisy lunatics'—one in seven of the 560 inmates being insane. This 'tall, gloomy brick building' stood on the site now occupied by Nos 143–157 Farringdon Road. (fn. 52)

14, 15. Clerkenwell Workhouse, Coppice Row, in 1882, shortly before demolition, and (below) ground plan in 1874

The original structure—a 'large, plain, commodious brick house'—was erected in 1727, after several years' search for a suitable location; an infirmary was built at the rear in 1729. The site, fronting what was then Coppice Row, was taken on a 122-year lease from Walter Baynes and Robert Warner. (fn. 53)

In 1774, with a rising problem of poverty in Clerkenwell, the parish obtained an Act of Parliament for improving poor-relief arrangements, including the enlargement or replacement of the workhouse. (fn. 54) But it was not until 1790 (and after a further local Act), that anything was done. The existing workhouse was more than doubled in size, making a long, roughly symmetrical building, with a grandly pedimented central section for staff and administration, flanked by dormitory wings: the old building survived as the male wards, the original division between (presumably) male and female accommodation remaining apparent in plan and elevation (Ills 14, 15). A laundry was added to the south of the infirmary in 1829. (fn. 55)

The workhouse was badly affected by the excavation for the Metropolitan Railway in the 1860s, and was only saved by a system of underpinning devised by the architect W. P. Griffith, later augmented by shores and tie-rods. (fn. 56) Proposals were made in 1868 to pull down the workhouse and put up a new one at Highgate, but these came to nothing, and in the following year the Clerkenwell Board of Guardians became part of the Holborn Poor Law Union. (fn. 57) In 1879 plans for complete rebuilding on the site were prepared. The new building, which was to have included relief offices and dispensaries, would have been eight storeys high, with the paupers occupying the five upper floors. This scheme was vetoed by the Local Government Board, on the grounds that the development was too much for such a small and constricted site. A new Holborn Workhouse was subsequently built in Merton, and offices and a dispensary in Clerkenwell Road (see Survey of London, volume xlvi). The redundant building was finally demolished towards the end of 1883. (fn. 58)

The site was occupied from 1885 by a temporary iron board school, before being redeveloped in the 1890s with warehouses, numbered in Farringdon Road; for these buildings see Survey of London, volume xlvi. (fn. 59)

The district after 1811

A small amount of building took place on the Jervoise estate towards the end of the eighteenth century as old leases fell in, with several houses being rebuilt in Great and Little Bath Streets and Great Warner Street, for example. (fn. 60) Also, by 1803 some vacant land at the northeastern end of Baker's Row had been developed with warehousing and two courts of small cottages, Providence Place and Charles Place. (fn. 61) But for the most part the estate at the time of its sale in 1811 was as first developed in the 1720s–40s. The first significant change to follow the sale was the building over of the garden at the Cold Bath, which quite destroyed any sense of a formal square.

By the mid-nineteenth century Coldbath Fields had to a large extent lost its residential character and most of the houses were used as workshops, warehouses or shops. Henry Mayhew, writing in the 1850s, found the former 'capital town mansions'—a slightly exaggerated description of the houses near the Cold Bath—'dingy and distressed', in use as old furniture stores or lodging-houses for single men. But there were also many of the specialist craftsmen found throughout Victorian Clerkenwell, such as jewellers, cabinet makers and scientific-instrument makers. (fn. 62) The construction of Farringdon Road and the Metropolitan Railway in the 1850s and 60s involved the almost complete redevelopment of Coppice Row, and brought about large-scale commercial and industrial building in and around Crawford Passage and Ray Street. Even more destructive was the creation of Rosebery Avenue in 1885–92.

Where pockets of old buildings survived, they were likely to be occupied by Italian immigrants, living in crowded and insanitary conditions, and chiefly employed in the ice-cream trade, or other street-based activities such as organ-grinding, the hawking of plaster figures and, in the winter, hot-chestnut vending. The Italian quarter had spread north here from its original nucleus in and around Hatton Garden and Saffron Hill, established by northern Italian craftsmen—scientific-instrument makers, glassblowers, engravers, mirror-makers—in the 1820s and 30s. Swollen by successive waves of migrants, increasingly of unskilled workers from the poorer, southern Italian regions, and driven out of Holborn by slum clearance and improvements, the Italian community was at its peak in the first three decades of the twentieth century (Ill. 16). (fn. 63)

There were highly skilled Italian craftsmen in the Coldbath Fields district, but ice-cream was by far the dominant trade. By c. 1900 there were thought to be more than 900 ice-cream barrows in Clerkenwell, many of them wheeled out from the Warner Street area, where ice-cream was made in makeshift factories in back-yards and livingrooms (Ill. 17). (fn. 64)

16. Italian procession in Farringdon Road, July 1933

17. Italians in Caroline Place, off Baker's Row, c. 1900. At the far left is a barrow with metal canisters used for ice-cream

In the late 1890s one of Charles Booth's researchers

found pockets of very rough and criminal elements

throughout the area, both Italian and English. A few years

earlier, in April 1894, an Italian anarchist was arrested with

a bomb on his way to his lodgings in Warner Street. (fn. 65) In the

1920s Arnold Bennett drew a picture of a sordid locality:

Coldbath Square easily surpassed even Riceyman [i.e.,

Granville] Square in squalor and foulness; and it was far more

picturesque and deeper sunk in antiquity, save for the huge,

awful block of tenements in the middle. The glimpses of interiors were appalling. At the corners stood sinister groups of

young men, mysteriously well dressed, doing nothing whatever, and in certain doorways honest-faced old men with mufflers round their necks wearing ancient pea-jackets. (fn. 66)

The area suffered badly in the Second World War. In September 1940 and May 1941 high-explosive bombs caused considerable damage in Warner Street, near the Rosebery Avenue viaduct, and by the end of the war much of Coldbath Square, Baker's Row, Topham Street and Warner Street had been declared clearance areas. (fn. 67) The war also saw the end of the Italian colony as it had been. Many of the inhabitants were interned or deported to Canada and Australia, and after the war the Italian community in Clerkenwell began to disperse to outlying parts of London and beyond. With the decline in industrial activity some former industrial buildings have been converted to apartments in recent years.

Standing Buildings

Very little building fabric of earlier date than Rosebery Avenue remains throughout the district. Of the original early Georgian development, the only buildings to survive more or less intact are Nos 47–57 Mount Pleasant (see below). One of the houses in Cobham Row, rebuilt or largely rebuilt in the early nineteenth century, survives as No. 40 Rosebery Avenue (see page 136), as does a short row of similar date at Nos 33–37 Eyre Street Hill (below); but most of the old houses have been pulled down long ago and the sites merged for building factories and warehouses.

All the eighteenth-century public houses in the area have been rebuilt or have disappeared entirely. The Apple Tree in Mount Pleasant was rebuilt in the 1870s (see below), and the Coach and Horses in Ray Street in 1897 (Ill. 18). (fn. 68) The Horseshoe and Magpie at No. 5 Topham Street, rebuilt for Watneys in 1939 in very plain neoGeorgian, remained a pub until recent years, and is now converted to offices. (fn. 69)

18. The Coach and Horses, Ray Street, in 2006

In the vicinity of Ray Street, Warner Street and Crawford Passage are a number of fairly large mid Victorian and later commercial and industrial buildings, replacing many small houses, cottages and workshops. Adjoining the Coach and Horses, the building numbered 24 Ray Street and 1 Crawford Passage dates from 1892, and was first occupied by Maclure & Co., lithographers. (fn. 70) Nos 2–5 Crawford Passage comprise a range of warehousing and factory buildings, erected in 1877 and converted into flats in 1996–7. They appear to have been built for the engineer Frederick George Underhay, manufacturer of valve water-closets. (fn. 71) No. 6 Crawford Passage is of similar date, and occupies the site of the Pickled Egg, which closed about 1874. (fn. 72) Nos 15–19 Baker's Row (Caslon House) was built on a bombed site in 1956–7 as a joinery works for J. Wardley & Sons Ltd, manufacturers of X-ray protective panelling, screens and cabinets. The second floor was added for the firm in 1976. (fn. 73) No. 20 Baker's Row, another very plain industrial building, dates from 1876 and was occupied from then until the early 1950s by Ramsden, Lankester & Co., an old-established firm manufacturing colourings for wine and spirits. (fn. 74)

19. Nos 47–57 Mount Pleasant (left to right) in 1947

Nos 47–57 Mount Pleasant

This short row of houses, the last substantial remnant of the original Baynes—Warner estate development, was coincidently the first part to be built, in 1719–20 (Ills 19, 21). It was built under the name Dorrington Street, and renumbered as part of Mount Pleasant in 1875, along with Cobham Row and Baynes Row. Several of the houses were complete by June 1720, and all but one were inhabited by mid-1723. (fn. 75) At the east end, on the corner of Warner Street, the Apple Tree public house was built in 1725–6; another house, latterly No. 59 Mount Pleasant, was added at the west end c. 1796. (fn. 76) This house was demolished in the late 1950s, along with Nos 61–75 Mount Pleasant (across the parish boundary, in Holborn), to make way for a block of flats, Laystall Court. (fn. 77)

20. Nos 55 and 57 Mount Pleasant, first-floor plans in 2004

Dorrington Street was named after a City bricklayer, Thomas Dorrington, who himself leased two of the houses, Nos 55 and 57. (fn. 78) The other building lessees were William Newman, joiner, of St Clement Danes (No. 47) and Thomas Scott, mason, of the City (No. 51). No. 49 was built at his own expense by John Warner as 'pumppriming' for the development generally. Leases of the adjoining houses describe No. 53 as having been built by the carpenter and surveyor Richard Grimes, and as no building lease seems to have been made out to him, this house may have been the one known to have been built at Warner and Baynes' joint expense with the same purpose. (fn. 79)

21. Mount Pleasant in 1879, looking south from the corner with Phoenix Place

The houses are typical of the best parts of the estate: three-storeyed, with cellars (some with later attics), three windows wide on frontages of 16–18 ft, conventionally planned with side-passages and dog-leg staircases, and lined with plain deal panelling. Unlike the rest of the row, Nos 55 and 57 were built as a mirrored pair (Ill. 20).

On the front of Nos 55–57 is a stone tablet inscribed 'Dorrington Street 1720', with a surround and entablature of moulded brick. A similar tablet survives from the demolished houses north of Warner Street, originally to have been Baynes Street but later called Baynes Row. Now painted over, it is mounted on the loading-bay wall of the present Nos 29–39 Mount Pleasant, on the corner of Warner Street. It was taken from the old No. 41 Mount Pleasant on this site, where it was set beneath a more elaborate panel of moulded brick incorporating the initials of the builder, John Pankeman, and the arms of the Tylers' and Bricklayers' Company. (fn. 80)

No. 51 was occupied from the end of the eighteenth century by John Pyrke, a tea-urn maker. He took over No. 53 as well in the 1830s, and the firm of John S. Pyrke & Sons continued at both houses, which were thrown into one, until the late nineteenth century. Pyrkes were presumably responsible for the stuccoing of the fronts. The houses remained in single occupation until recent years, latterly as the premises of O. Committi & Son Ltd, makers of barometers, thermometers and spectacles. They were converted for residential use in 1996. (fn. 81)

Apple Tree public house, No. 45 Mount Pleasant

The building lessee of the Apple Tree, together with two adjoining houses in Warner Street (later Nos 2 and 4), was Joseph Sage, a plasterer. He insured the new tavern in 1726 for £400. (fn. 82) According to Pinks, the landlord 'at one time' was the Islington strongman Thomas Topham, after whom Topham Street is named. (Topham, who killed himself in 1749 after murdering his wife, performed a prodigious weight-lifting feat in Great Bath Street in 1741 to celebrate Admiral Vernon's capture of Carthagena from the Spanish—raising three hogsheads of water on a specially constructed scaffold.) His name never appears in the ratebooks at the property, however. (fn. 83) In later days the Apple Tree was apparently a favoured first resort for discharged prisoners from the House of Correction across the road, and as a gimmick handcuffs were used as bellpulls in the taproom. (fn. 84)

The pub, which had been 'newly fronted and modernised' about 1848, was rebuilt in 1872 (Ill. 22). The twostorey extension was built in 1925, in the same style, replacing Nos 2 and 4 Warner Street. (fn. 85)

The Rosebery development

The site of Coldbath Buildings, together with the area adjoining to the south and east bounded by Warner Street and Baker's Row, was redeveloped in 1988–90 by Kinson Property Ltd, in partnership with the merchant bank Guinness Mahon. Built to designs by the Kinson Group, the new development, named Rosebery, comprises threestorey light-industrial units on Baker's Row and Warner Street, four-storey office units arranged in a courtyard on Coldbath Square, and a six-storey residential block, Rosebery Court, facing Rosebery Avenue (Ill. 6). (fn. 86)

22. The Apple Tree, Mount Pleasant, in 2006, showing Warner Street frontage

23. Warner House, Warner Street, in 2006

24. Warner House, interior before conversion

Warner House, Nos 43–49 Warner Street

This is an early and slick example of the 'loft' genre in London, dating from the mid-1990s. A stylized Modernist conversion of a modest industrial building of the 1930s, Warner House (sometimes called the Warner Building) draws its inspiration particularly from Richard Meier's High Museum in Atlanta of 1980–3 (Ill. 23).

Warner House (its original name) was erected in 1937–8 for Shropshire House Ltd, to designs by Waite & Waite of Cavendish Square. It was built with a reinforced-concrete frame, faced externally in stock brick, and reinforced-concrete floors and roof on the recently developed 'Diagrid' system, avoiding the need for internal supports (Ill. 24). The contractors were E. A. Roome & Co. Ltd. Among the first occupants were printers, manufacturers of lenses and clothing, and the Post Office Stores Department. The printing firm remained at the building until the late 1980s. (fn. 87)

The conversion to loft apartments was designed and carried out in 1993–6 by Eastglen Property Services Ltd, in conjunction with GJP Practice and Vincent Grant Partnership. This involved the addition of a steel-framed penthouse floor of double height (curved at the corner, unlike the lower storeys), with flying buttresses. The original small-paned steel windows were replaced, and the walls rendered white. Inside, the individual apartments, sold as shells, range in size from 700 to 2,000 sq.ft. (fn. 88)

Nos 31–37 Eyre Street Hill

These few modest buildings are the last remnants of Little Bath Street, which was laid out in the mid-1720s at the southern end of the Baynes—Warner estate, next to the Fleet, as a continuation northwards into Clerkenwell of Eyre Street (now Eyre Street Hill, see Ill. 25); they were renamed and renumbered in 1937. Today the oldest structures are the small, single-bay houses with shopfronts at Nos 33–37, dating from the early nineteenth century and fairly typical of the rebuilding that took place in the area at that time. Nos 33 and 35 were erected as a pair around 1812 by Thomas Abbott, builder, of Leather Lane. (fn. 89)

By about 1900 these properties were at the centre of the Italian colony, and were populated mostly by families of ice-cream vendors and street-hawkers. (fn. 90) Chiappa Ltd, a well-known firm making and repairing pianolas, barreland fairground-organs, was based at the present No. 31 from about 1877 (originally as Chiappa & Fresani). Still operating in the late 1980s, the firm was the last of its kind in Britain. Their factory-workshop, rebuilt probably in the 1910s or 20s, has since closed and been converted, though its facia has been retained. (fn. 91)

25. Nos 31–37 Eyre Street Hill (left to right) in 2006

Back Hill electricity sub-station, Warner Street

This complex dates mostly from 1956–7, when the London Electricity Board extended an earlier yard established in the late 1920s by its predecessor, the London County Council's County of London Electric Supply Co. The 1950s buildings, designed by the LEB's Architect's Section, are of reinforced-concrete and steel frame construction with elevations of buff-coloured brick and glass block. They match the original building in the southeastern corner of the site (Ill. 26). (fn. 92)

26. Back Hill sub-station in 2006

North of Mount Pleasant

Eighteenth-century building in Gardiner's Field, north of Dorrington Street and Baynes Row, was mixed, consisting of a few houses, a distillery, a hospital for treating and inoculating against smallpox, and, towards the end of the century, the biggest development, a prison. It was never likely that the new residential suburb on the Baynes—Warner estate would extend much over this northern area, the ground being poor for building, uneven and badly drained, and long used for dust-heaps and laystalls. Even after the biggest of these tips, the 'Mount Pleasant', was cleared for the building of the prison, one large mound remained, just over the parish boundary in St Pancras; and refuse continued to be dumped in the Fleet and outside the prison walls into the 1820s and 30s. (fn. 93) Almost the whole of Gardiner's Field was eventually subsumed by the prison during the Victorian period, and the prison itself was completely redeveloped in the early twentieth century by the Post Office.

West of the prison site, the remnants of the original eighteenth-century building and nineteenth-century rebuilding survived until recent years. The oldest buildings now standing on the north side of Mount Pleasant are parts of the postal sorting office dating from the 1920s.

27. No. 6 Mount Pleasant, part of Bowen & Co.'s Phoenix Brass Foundry, in 1965. Demolished

Phoenix Iron Foundry site

In 1734 William Vernon, distiller, took a lease from Baynes and Warner of the ground on what is now the corner of Mount Pleasant and the west side of Phoenix Place, backing on to the Fleet ditch to the north and west. There were then several houses, and a building described as having been used recently as a lamp-black house. As the lease was for 51 instead of the usual 61 years these had very likely been recently completed under an old building agreement. (fn. 94) A distillery was built here about 1740, occupied for some years by Maynard & Co. (fn. 95) This was converted to, or rebuilt as, the Phoenix Iron Foundry, probably about 1808. This was the date on a Coade stone plaque, decorated with cannon balls and gun-barrels, formerly over the entrance to the works, latterly Bowen & Co.'s Phoenix Brass Foundry, at No. 6 Mount Pleasant (see Ill. 27). (fn. 96)

Phoenix Place seems to have originated as a cul-de-sac giving access to part of the foundry premises, and was later extended along the west side of Coldbath Fields Prison to link up with Calthorpe Street. The Phoenix works was extensively rebuilt in the early 1850s with new furnaces and a substantial warehouse along Phoenix Place, which survived until the 1960s. (fn. 97) All the buildings on this site have long been cleared and it remains vacant.

London Smallpox Hospital

The charitable institution known variously as the London Smallpox Hospital or the Middlesex County Hospital for Smallpox and Inoculation was established in 1745–6, reputedly the first foundation of its kind in Europe. A series of houses was occupied in the West End, Finsbury and Bethnal Green, none of them for long, and in 1748 plans were made to erect two separate buildings, for inoculation and for the treatment of smallpox victims, on fifteen acres of land in Clerkenwell belonging to the Rev. John Lloyd—the future Lloyd Baker estate. (fn. 98) Evidently nothing came of this scheme, and by 1750 the institution was running premises at three locations elsewhere: an inoculating-house in Old Street; a house in Frog Lane, Islington (now Popham Road), for receiving inoculated patients once symptoms had appeared; and a receivinghouse near by for patients afflicted with the full-blown disease, in Lower Street (now Essex Road). (fn. 99) In 1752 the trustees of the institution acquired the lease of the Sir John Oldcastle's property in Coldbath Fields, not far from Lloyd's ground, converting a 'spacious building' there. Elms were planted to screen the new hospital from the inn, which appears to have stood very close, a little to the north. The hospital opened in March 1753, taking patients from both Frog Lane and Lower Street. (fn. 100)

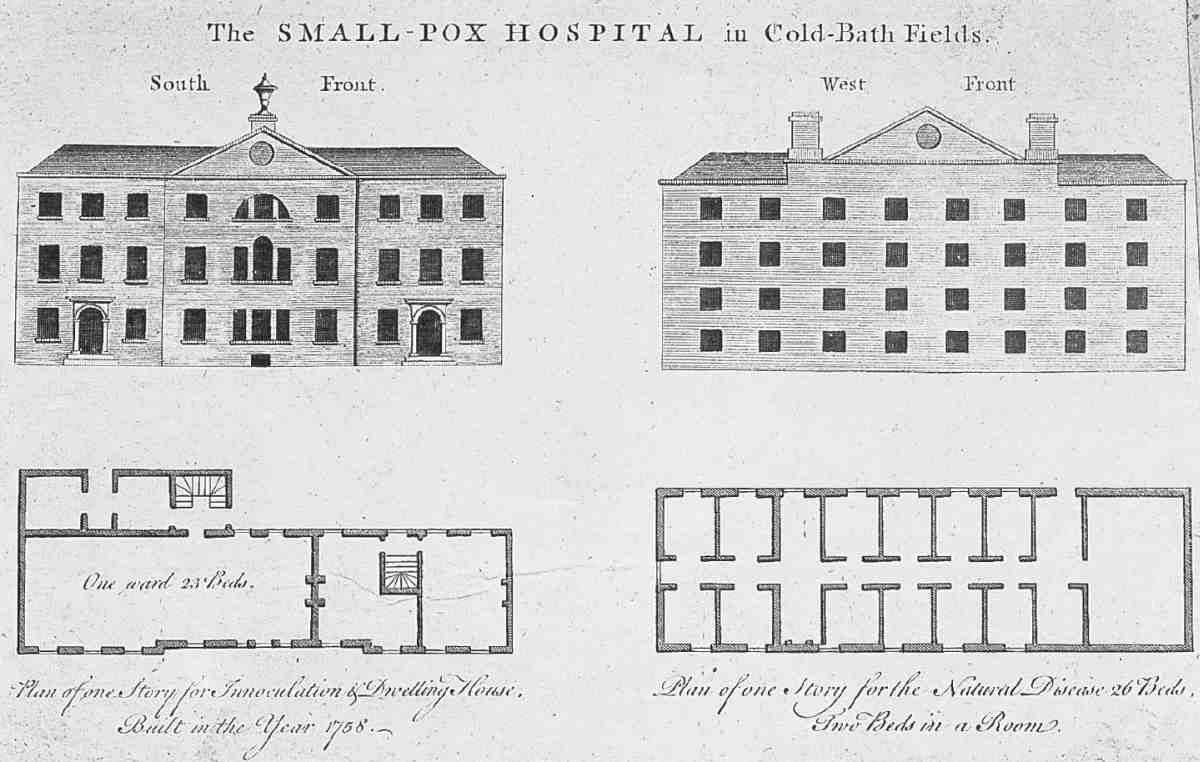

28. Smallpox Hospital, Coldbath Fields, elevations and first-floor plans, c. 1760

There was immediate opposition. The Vestry filed a bill of injunction in Chancery to stop the hospital going ahead, citing the 'terror' of the disease in the neighbourhood and threats by tenants to leave. Lord Hardwicke, presiding, refused an injunction, instead praising the new establishment and the appropriateness of its situation. Local opposition persisted once it had opened; discharged patients came in for abuse, and were obliged to leave under cover of darkness for their safety. (fn. 101)

The constructional history of the hospital is far from clear, but it is evident that the original building was either rebuilt or altered and enlarged over the next few years, perhaps from 1754 when the head lease was assigned to the trustees, certainly by c. 1761 when a new long lease was granted by Robert Warner, the freeholder. (fn. 102) (If rebuilt, it almost certainly stood on the old foundations, for in outline it matched closely the footprint of a building in the same position shown on Rocque's map published in 1747.) (fn. 103)

Plans and elevations probably published around this time, for fund-raising or other publicity purposes, show the two ranges of the L-shaped building; the main (south) range, comprising inoculation wards and staff quarters, is stated to have been built in 1758 (Ill. 28). The west wing, mostly divided into two-bed sick-rooms, is not dated, and had perhaps not yet been completed. As built, this wing was, like the main range, of two full floors and an attic, not of four low floors as indicated on the drawing (Ill. 29). However, all three floors had the small windows shown on the drawing, perhaps to screen patients from the outside world. If light and views were not a priority, fresh air evidently was, for the hospital was fitted with Dr Hale's ventilators and trunking. (fn. 104)

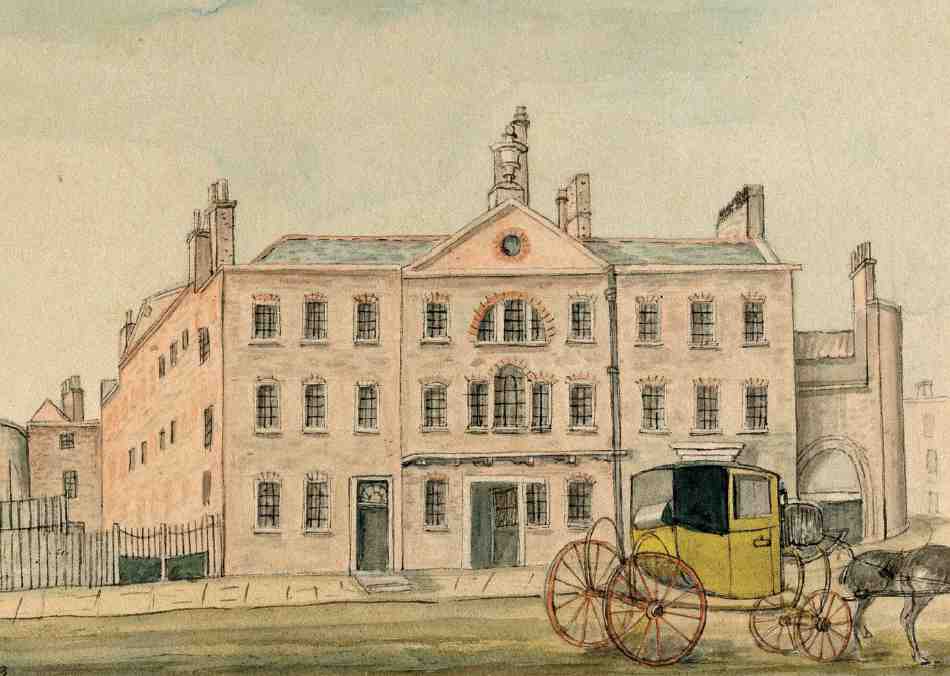

29. Former Smallpox Hospital, Coldbath Fields, south elevation in 1823. Demolished

Sir John Oldcastle's, described in the 1761 lease as 'very ruinous', (fn. 105) was demolished in 1762 and a wash-house and laundry for the hospital built in its stead. (fn. 106)

In 1793–4 a new smallpox hospital was erected at St Pancras, on freehold land owned by the governors. The redundant Coldbath Fields building was subsequently used as a distillery, and for other commercial purposes, until the mid-1860s, when it was demolished for an extension to Coldbath Fields Prison. (fn. 107)

Oldham Place and Oldham Gardens

In 1813 the one-time smallpox hospital was acquired by James Oldham Oldham, a trustee of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, with a view to its being used as the site of a replacement for Spa Fields Chapel in Exmouth Street (Exmouth Market). (fn. 108) Oldham died in 1823, having given the property to the Connexion, and the yard and garden were let as building lots. Oldham Place and Oldham Gardens, a row of houses with cottages behind, were built here in 1824–8, the speculation of Christopher Cockerton, a painter of Aldersgate Street. (fn. 109)

With the incorporation of the hospital site into the prison in the 1860s, Oldham Place and Gardens became half encircled by the prison wall, as if in a cliff-side cove. Oldham Gardens was pulled down in the early 1890s for the development of Mount Pleasant Sorting Office. The houses in Oldham Place, from 1883 Nos 161–179 Farringdon Road, renumbered 177–195 in 1898, were demolished c. 1900 for the extension of the adjoining parcel-sorting office (see Ills 32, 36). (fn. 110)

Coldbath Fields Prison

Coldbath Fields Prison was built in 1788–94 as the Middlesex House of Correction, replacing the seventeenth-century Bridewell in Corporation Row. It was one of many prisons erected in England during the last three decades of the century, in large part in response to the penal reform campaign of John Howard, whose ideas about design and planning it was intended to embody. But it was no model prison. The completed building was a cutdown version of that planned, and to some extent badly built. The first governor, Thomas Aris, a baker who supplied bread to the county gaols, proved corrupt and incompetent, and the prison soon acquired a reputation for brutality, mismanagement and overcrowding. Before long, too, it was being used for the detention without trial of suspected traitors—political prisoners who endured the same harsh regime as convicted felons. With its bad reputation came its nickname the Bastille (later corrupted to the Steel). However, reforms were put in hand under Colonel G. L. Chesterton, governor from 1829, who managed to turn it into reputedly the best-managed prison in London. (fn. 111)

Among those held at Coldbath Fields prison were Leigh Hunt's brother John, convicted of libelling the Prince Regent as a 'fat Adonis of fifty', and the Cato Street conspirators.

The buildings were much added to during the nineteenth century, with cell wings on a new radial plan, and treadmill houses as part of the apparatus of hard labour. They were demolished from the late 1880s as the site was redeveloped by the Post Office for parcel sorting and other purposes under the name Mount Pleasant, the ironic appellation of the rubbish-tip formerly on the site.

Design of the new prison, initially intended for the Bridewell site with some enlargement, was overseen by a committee of justices convened in January 1784. Among their number were the architects Sir Robert Taylor, James Paine, Robert Mylne and Henry Holland. (fn. 112) But it was another member, the architect-developer Jacob Leroux, who drew up the first plans. Two outside architects, James Burton and Robert R. W. Brettingham, submitted designs of their own, prompting the committee to hold a public competition, for which twenty entries were received. This was won in December 1784 by Aaron Henry Hurst, whose plans drew heavily on the work of William Blackburn, the architect who had most successfully realized Howard's ideas on separate or 'cellular' accommodation.

Gardiner's Field was suggested as a better site by Mylne and, with Howard's endorsement, the ground was purchased in 1785–6, for £4,350. (fn. 113) Hurst's scheme, having survived both a charge of plagiarism brought by Blackburn and the change of site, was altered by Leroux, with suggestions from others on the committee. It was this revised scheme which was engraved by Charles Middleton in 1787–8 for the use of prospective tenderers. (fn. 114) Although some contemporary accounts name Paine or Taylor as the architect of the prison, it is clear that neither had more than an advisory role. (fn. 115) Considerable changes to the published design were made during construction by Thomas Rogers, the county surveyor, who took over from S. P. Cockerell as clerk of works at the end of 1789.

Though much larger and more airy than Corporation Row, the site was a difficult one. Not all of the ground acquired by the county was used: the prison walls formed a nearly rectangular enclosure in the middle of Gardiner's Field, set well back from Bagnigge Wells Road and Baynes Row, but extending westwards to the bank of the Fleet. Close to the river it was marshy and steeply sloped, requiring deep, arched foundations and much building-up with earth: the finished building was said to have 'as many bricks laid under ground … as appear in sight'. (fn. 116) Trenches as deep as 25 ft had to be cut through the soil to reach the clay bed, work for which the labourers demanded and received increased wages. Some levelling of the Mount Pleasant dust-heap had already been carried out by the last tenant of Gardiner's Field, and what remained was now used as infill. The ground works were not, however, successful and twenty years on the prison was showing serious decay, partly the result of unstable foundations. Excavations in 1994 revealed the deep foundations to have been made of soft red brick; on the drier, eastern part of the site extensive use had been made of timber piling and planking. (fn. 117)

While the foundations were expensive and difficult, the construction above ground was fraught with problems too, the work being hampered in 1790–2 by shortages of materials. Long spells of wet weather resulted in a dearth of bricks, and those available were of poor quality. Stone, too, proved hard to obtain. In particular, shipments of Purbeck stone from Messrs Chinchens of Swanage were held up by a combination of contrary winds and fear of pressgangs. In the end, the building had to be completed without much of the intended stone detailing, leaving its elevations of grey stock brick severely plain. (fn. 118)

Rising costs provoked accusations of jobbery and fraud on the part of the builders and their suppliers, even of collusion by magistrates. With the long delays and increasing expense it became necessary to make drastic cuts to reduce the scale of the work. The final cost, including purchase of the site, was between £70,000 and £80,000, much of it raised through a tontine secured on the county rate. (fn. 119)

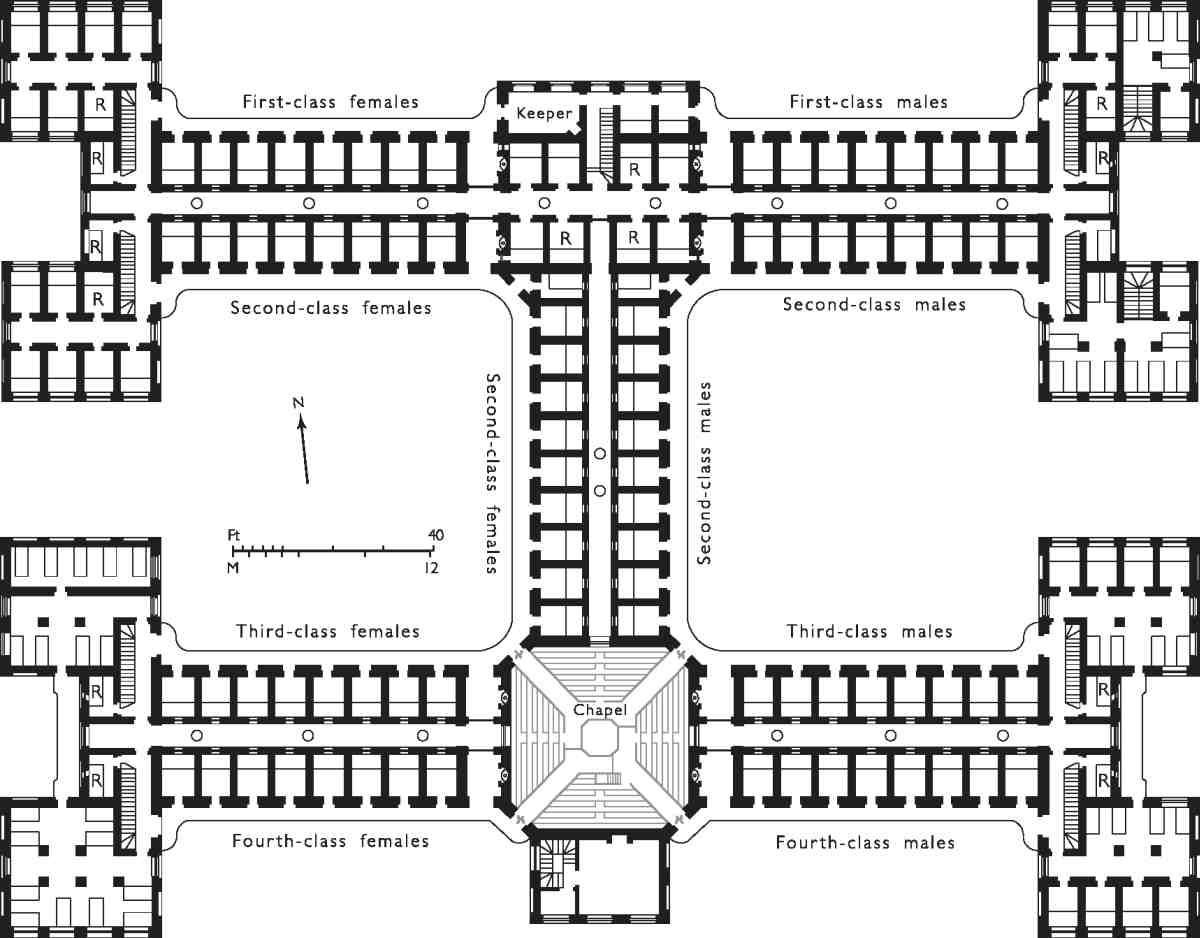

No plans of the building as completed survive, but later plans and views give a general impression (Ills 30, 32). (fn. 120) The first floor as proposed to be built is shown in Illustration 31. This was for males; female prisoners were to have occupied the floor above, while much of the ground floor would have been given over to arcaded workrooms and stores, called 'working piazzas' by Leroux. This arrangement, a standard feature of prison-building at the time, would have been well suited to the damp site. Overall, the design, with its slightly elaborated H-plan, bears strong similarities to William Blackburn's design for Gloucester County Gaol (1785–91). The majority of the cells were arranged on either side of corridors for the warders (the 'keeper's passages'). Small circular gratings on the corridor side of these cells would have provided fresh air, via a series of iron-barred openings in the corridor floors, but little or no natural light, and were presumably intended as well to allow observation of the cells by the warders. Access to and from the cells, however, was to have been via outside galleries or walkways: ensuring that the prisoners of different categories on either side of the corridors were isolated from each other. (fn. 121)

The most drastic change made by Rogers was the omission of almost the entire second floor, of which only the upper chapel was retained. But it was also necessary to make significant changes to the planning of the ground and first floors. What survived intact was the overall footprint of the building, though the small ground-floor pavilions or lodges, shown closing the uprights of the 'H' on the published block-plan and elevations, were omitted.

The second-floor cells having been lost, it became necessary to convert some of the ground-floor arcades into single cells; as it was the overall capacity was reduced from about 400 prisoners to 328. (fn. 122) For further economy, the proposed access galleries were dispensed with and the cells turned round so that the doors opened off the corridors. On the ground-floor, the cell-doors did open on to the yards, but this arrangement was changed in the early 1800s after a number of escapes. In addition to 200-odd single cells, there were several larger, communal rooms, presumably housed in the short corner wings, one of which, on the upper floor, was later used for holding state prisoners. A proposed detached infirmary was also abandoned, and the governor's house was built smaller than planned.

The entrance gateway, on the south side, was of Portland stone, and ornamented with sculpted fetters. These decorations, and the inscription '1794 Middlesex House of Correction 1866' were removed when the Post Office took over the site. The gateway was finally demolished in February 1901 (Ill. 34). (fn. 123)

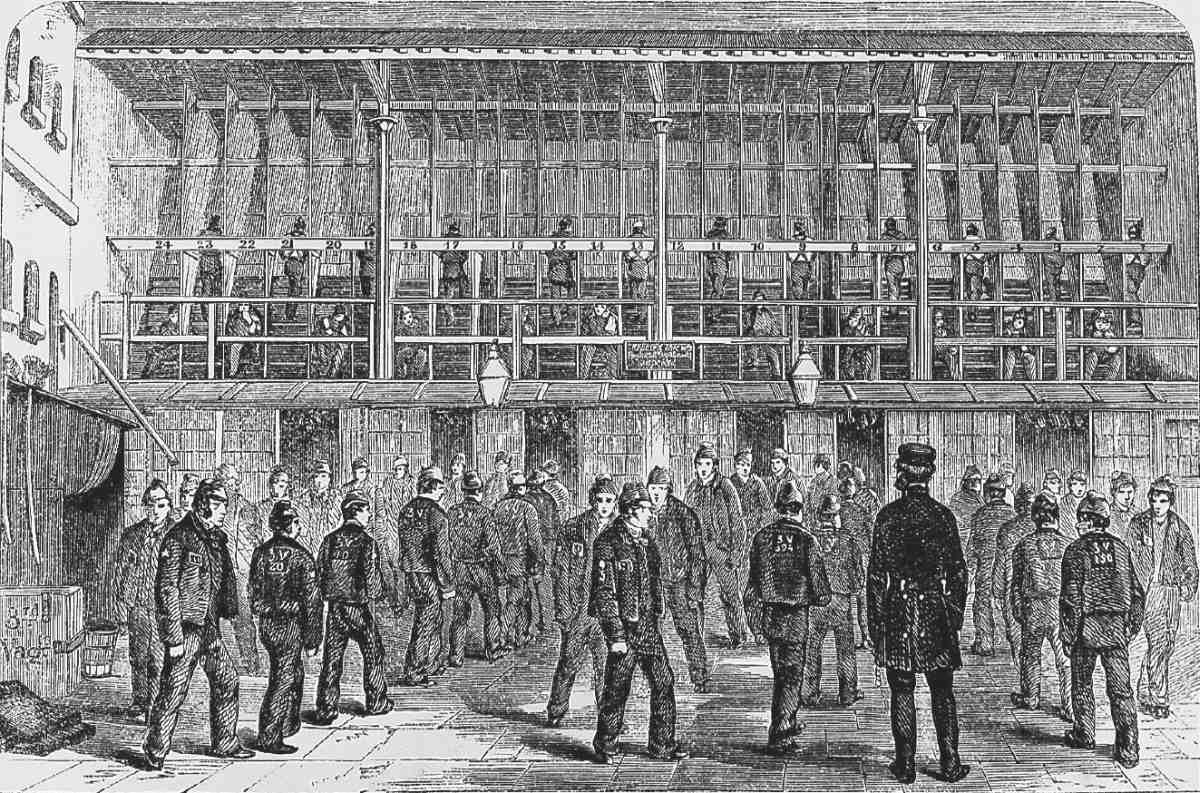

Coldbath Fields' grim reputation was reinforced by the regime of hard labour introduced in the early 1820s. Central to this was the treadwheel. The first was installed in 1822 to designs by its inventor (Sir) William Cubitt; more were added in the 1830s (Ill. 33). These early wheels served no practical purpose, resistance being provided by an adjustable horizontal revolving beam or 'sail', but in later years a single large treadwheel was used to grind corn for bread baked at the prison. (fn. 124) The last to be built, in 1882, was the largest in the country, and could take over 350 men. It was re-erected at Pentonville after the closure of Coldbath Fields. (fn. 125) Other forms of correctional 'discipline' included the entirely futile hand-crank (a drum embedded in a box of sand or gravel, which prisoners turned by hand, for about 8½ hours a day) and 'shot-drill' (the lifting and lugging at command of cannonballs from one end of a patch of ground to the other, and back again). Productive labours included mat-making, washing, cleaning, tailoring and oakum-picking. The workrooms were decorated with quasi-inspiring texts ('Behold how good and pleasant it is for brethren to dwell in unity'), said to be a peculiarity of this prison.

Coldbath Fields Prison. Demolished

30. Coldbath Fields prison, from north-west, c. 1810, with part of the Fleet river in foreground

31. First-floor plan, as designed 1788. 'R' denotes rooms for 'refractory' or difficult prisoners; circles in the corridors are grated openings

32. Bird's-eye view of prison at its greatest extent, 1885

33. Treadwheel, Third Vagrants' Yard, c. 1862

34. Former prison gateway, c. 1900

In 1834 the silent system of management was adopted, officers and selected inmates being posted in the rooms to prevent any communication between prisoners by word, sign or gesture. (fn. 126)

The 1820s saw a great increase in the numbers of prisoners and the prison was enlarged accordingly. In 1823 Robert Sibley, the county surveyor, was asked to design buildings for Coldbath Fields to accommodate women prisoners and vagrants, and the following year work began on a new boundary wall, eighteen feet high and enclosing the whole of the county's land at Gardiner's Field. (fn. 127) Work on the wall was suspended for a few months in 1824 while a new road behind the prison was in contemplation. This would have connected the Marquess of Northampton's ground with Lord Calthorpe's estate to the west (see page 243), but it was not proceeded with, though a sewer was built along the route, which still runs beneath Mount Pleasant sorting office. In 1825 the justices acquired a strip of land from Calthorpe on the west bank of the Fleet, still open at this point, diverting the river to a new covered sewer outside the new prison wall. Hone's Table Book illustrates the wall under construction, perched on high arched foundations. (fn. 128)

The proposed vagrants' annexe, designed by Sibley, was not erected until 1830, and stood at the southwest corner of Gardiner's Field, where the new prison wall had been carried on alongside Baynes Row. It was planned on the new radiating principle, with wings extending from a central core. A similar building for female prisoners followed in 1831–2 on the Bagnigge Wells side of the site, this by Sibley's successor William Moseley. (fn. 129) This was later the 'misdemeanants' prison, women being no longer sent to Coldbath Fields from 1850.

Further enlargement in the 1860s increased accommodation from about 900 cells to over 2,000, finally covering with buildings almost the whole area now occupied by Mount Pleasant sorting office, including most of the old smallpox hospital site (Ill. 32). This was the work of the then county surveyor, F. H. Pownall. The enlargement began in 1863–6, with more radial cell wings on former garden ground to the north, the cells planned under the guidance of Joshua Jebb, architect of the influential Pentonville Prison (1840–2). (fn. 130)

In 1866–70 Pownall added another 500 cells in two more ranges, including a long gallery or 'central avenue', in order to comply with legislation requiring all prisoners to be accommodated in single cells. (fn. 131) With the acquisition of the former smallpox hospital, the site was extended south and east, the old gateway being re-erected as part of a group of buildings including houses for the warder and gate-keeper. A large new range was erected in the courtyard behind, comprising staff rooms and offices beneath a lofty chapel. Brick built, with minimal stone dressings, this was of the plainest description of Gothic. Part of the hospital site was used for a new governor's house, in Italian-Gothic style (see Ill. 37). (fn. 132)

The Prison Act of 1877 transferred the administration and ownership of local prisons from county authorities to a new Prison Commission, under the Home Office. Most of London's outdated prisons were closed by the Home Office in the 1880s, the last inmates leaving Coldbath Fields at the end of October 1885. (fn. 133)

Hopes were entertained that the nine-acre site would be used for working-class dwellings or as a park, both much needed locally. The transfer of redundant prison sites to the Metropolitan Board of Works had been one of the recommendations of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes, enshrined in the 1885 Housing of the Working Classes Act. The MBW, however, declined to purchase the site, feeling that adequate provision for dwellings had been made in connection with its proposed new road, the future Rosebery Avenue. The county of Middlesex, too, was not interested in its re-acquisition, which could only have been made at a very high valuation of £186,900 (£120 per cell), set by the 1877 Prison Act. Its purchase by the Post Office from the Home Office was for just £96,000. Though the Post Office began using part of the site in 1887, the legislation needed to authorize the sale was not completed until 1889. London MPs (other than those holding government office) made a last-ditch attempt to save the site as an open space, petitioning the Treasury in June. (fn. 134) While this failed, provision was made in the Post Office Sites Act (1889) for the LCC to acquire part of the old prison for a public open space, or £10,000 to provide one elsewhere; this enabled the LCC to create Spa Green Gardens in Rosebery Avenue (see page 139). (fn. 135)

Mount Pleasant Sorting Office

Mount Pleasant, the Post Office's central sorting depot in London, is a byword for postal activity, famous for its frenetic Christmas workload. Six thousand men and women were once employed here in its Postal, Engineering, Stores and Customs departments. Though much run down since then, it retains its long-standing position as the largest mail-handling centre in the country. It is also the home of the British Postal Museum and Archive (Freeling House), opened in 1992. (fn. 136)

The importance of the facility has never been matched by its external appearance. In 1900, well before the present batch of buildings was erected, The Times dismissed the then newly completed Parcel Office as no more than 'a commodious shed'. (fn. 137) The unprepossessing yet not unmemorable combination of big buildings and open space that confronts the visitor to this vast site today is unlikely to survive much longer. At the time of writing (2007), there are plans for a mixed-use redevelopment of at least part of it, including the construction of a new mail-handling centre. (fn. 138)

Occupying the whole quadrilateral formerly taken by Coldbath Fields Prison, and bounded by Farringdon Road on the east, Mount Pleasant on the south, Phoenix Place on the west and Calthorpe Street on the north, the site of the sorting office divides visually into two parts. Clustered at its south end, massive blocks run westwards down the hill from the corner of Rosebery Avenue and Farringdon Road, where a post office for public use prefaces the small est of them. Built between 1920 and 1937, they are all in the inter-war economy style of the Office of Works. Their framed structures are rendered, with residually classical elevations and giant pilasters marking the main southern fronts along the sharp descent down Mount Pleasant. To the rear they present an uninterrupted north front of more than 150 m. Additions atop and around these blocks, plus unsympathetic alterations and a general lack of maintenance, have rendered this potentially monumental complex merely shabby.

35. Mount Pleasant Sorting Office, mail-van park and depot

The remainder of the site, perhaps 15,000 square metres in extent, consists on first impression of a disorderly parking lot enclosed by a high wall with piers and railings and a perimeter road immediately behind. Further back is a lower wall of modern date, shielding a large sunken yard. Here, visible only from the air or the north-west, vans and lorries are marshalled for basement access to the main sorting blocks (Ill. 35). From the architectural standpoint the sole feature of interest on this northern part of the site is the perimeter wall, essentially of late Victorian or Edwardian date but much damaged and altered. The best of the stone piers, topped with balls, are on the Phoenix Place side close to the main traffic entrance.

Early history, 1887–1900

It was in the 1880s that the Post Office bought the redundant Coldbath Fields Prison and redeveloped it as a central depot under the name of Mount Pleasant. The site was obtained principally for parcel and letter sorting, but brought together a number of functions from various locations, including telegraph engineering and storekeeping (Ill. 36).

Both the acquisition and the change of name— 'Coldbath Fields' being too tainted by association for respectable clerks to stomach—were due in large part to Frederick Ebenezer Baines, an Assistant Secretary of the Post Office and Inspector-General of Mails, who had organized the parcel-post service introduced in 1883. The potential of the former prison appears to have caught Baines's attention in January 1887, more than a year after its closure. 'Our first vital requirement', he wrote, 'is more space—in a convenient and central position if you will, but, anyhow or anywhere, more space'. (fn. 139) A single location was particularly needed for sorting and distributing parcels going to and from King's Cross, Euston and St Pancras stations, then dealt with chiefly by depots at King's Cross and Euston Square. The Polygon, adjacent to Euston station, had been considered as a site, and Baines, too, had pressed for the acquisition of Christ's Hospital in the City (later used for the King Edward Street extension to the General Post Office in St Martin's-leGrand). He thought also of Smithfield or 'the cheaper localities east or west of Aldersgate Street'.

Coldbath Fields had the double advantage of being very spacious, at some 7½ acres, and close to both the railway termini and St Martin's-le-Grand. This made it ideal not only for the parcel centre, but for taking on some of the huge letter-sorting activity at the General Post Office. As Baines recalled, the Secretary to the Post Office, Sir Arthur Blackwood, 'had no respite from my urgent appeals for its acquisition. He and the Postmaster—General listened and approved'. (fn. 140) By May 1887, the purchase of the prison from the Home Office had been agreed with the Treasury.

In the first instance, portions of the prison buildings were adapted for post-office use. Plans were drawn up by (Sir) Henry Tanner, Principal Architect to the Office of Works, for converting the treadmill house into a temporary parcel-sorting office, and the work was pushed forward to meet the coming Christmas rush. (fn. 141) In 1888 the prison chapel was taken over by the Money Order department, previously at St Martin's-le-Grand, while the kitchen, bakery and some cells north of the chapel were allocated to the Controller of Postal Stores. The gates, gatehouses and governor's house on Mount Pleasant were also initially retained.

36. Mount Pleasant Sorting Office, block plan in 1896

37. Mount Pleasant, looking west at junction with Rosebery Avenue, 1919. Former prison governor's house (far right) and adjoining early Post Office buildings, Mount Pleasant. All demolished. Bideford Mansions, Rosebery Avenue, at left

Some of these buildings, notably the Gothic-tinged chapel block and the governor's house, survived until after the First World War. But most of the southern part of the site was soon covered with new buildings for Post Office Telegraphs. The Telegraph Superintending Engineer's department was housed in a plain building at the corner of Rosebery Avenue and Farringdon Road. West of the former governor's house at the top of Mount Pleasant, a number of large buildings, mostly of four storeys, were erected in 1890–1 to Tanner's designs for the manufacture and storage of insulated cable and other telegraph plant. (fn. 142) The frontage building along Mount Pleasant, of austere brickwork with sash windows and occasional gables, was probably typical. Early in 1901 the prison gateway was pulled down to make way for an eastward extension to the telegraph factory. (fn. 143) As part of this new building the main entrance was shifted to the east, next to the former governor's house (Ill. 37).

Parcel Office (demolished)

The most important new building in the early phase of operations was the Parcel Office, begun in 1889 and completed in June 1900. The main purpose of this vast redbrick edifice, built in stages and covering the whole centre and northern end of the site, was to provide large expanses of open floor for the labour-intensive work of sorting.

The chief interest in the design of the Parcel Office is in the way large areas on three levels were lit naturally without recourse to a central light-well. An early plan by Tanner, made in May 1887, suggests a plain building of square outline two storeys above ground, broken up internally by a series of large single-storey sorting areas under glass roofs. (fn. 144) As executed, this plan was much modified. The four corners of the square were extended outwards to form pavilions providing offices and other accommodation, while along the centres between the pavilions were inserted large projecting loading bays for mail-vans with glass-canopied roofs, somewhat suggestive of a railway terminus (Ills 38–41).