Pages 52-83

Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

CHAPTER II. Exmouth Market Area

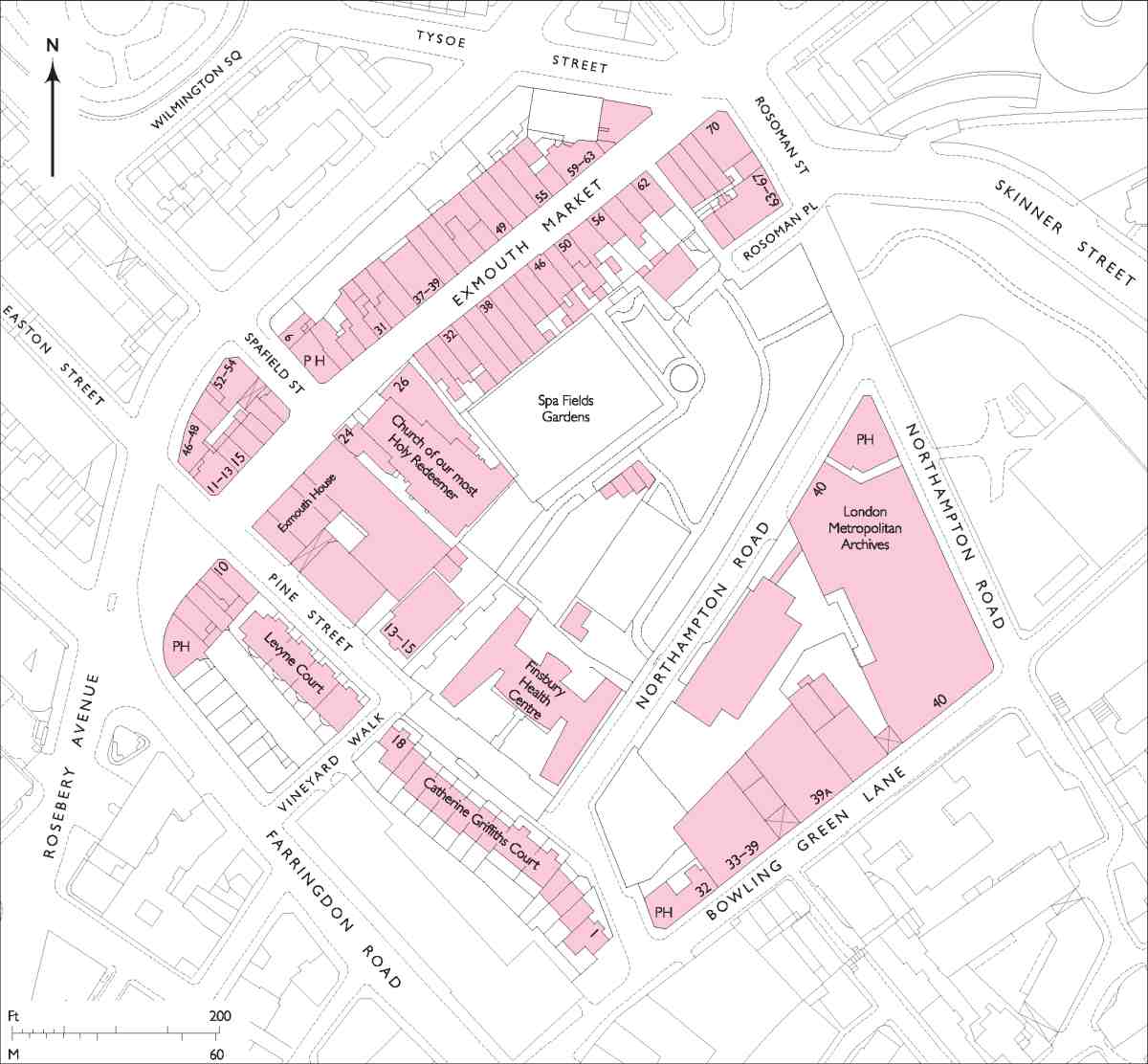

47. Exmouth Market area

This chapter describes the southern portion of the area once known as Spa Fields, which was the western of the two Clerkenwell estates formerly owned by the Marquesses of Northampton (Ills 47, 58). The larger northern portion is treated in Chapter X. An account of the eastern estate (Woods Close, now the Northampton Square area) is given in volume xlvi, Chapter XI, along with more detailed discussion of the ownership and management of the two Northampton estates generally.

Spa Fields took its name from the London Spaw, a public house, so called from 1685, where water from an ancient spring was sold for its medicinal properties. Before the dissolution of the monasteries Spa Fields was called Hyelie (hilly) Field or Lilliefield, and belonged to St Mary's nunnery immediately to the south. Roughly oblong in shape and about 29 acres in extent, it stretched northwards uphill from what is now Bowling Green Lane, and, again in modern terms, westwards from Rosoman Street and Amwell Street to Farringdon Road. It was probably used as arable, and by the sixteenth century as pasture; parts were used for brickmaking after the Dissolution. A piece to the south-west was, until c. 1800, a vineyard, said to have had monastic origins. (fn. 1)

The property came into Northampton hands through the marriage of the 2nd Lord Compton, later 1st Earl of Northampton, to Elizabeth Spencer, daughter and heiress of Sir John Spencer who had bought it in 1599. From Elizabeth's son Spencer Compton, the 2nd Earl, it descended to subsequent earls and, later, marquesses as parts of the Northampton settled estates. (fn. 2)

Tea-gardens and other resorts grew up in this area from the late seventeenth century, and house-building began to take off in the second half of the eighteenth century, spreading as these attractions went into decline. Historically, the line of what is now Exmouth Market marks the division between this early house-building and the much more extensive development to the north that followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars. But while the two sides of the street were built up in different periods, they were topographically part of a continuum extending north over the rest of the old Spa Fields. There Wilmington Square, conceived in 1817, was the centrepiece of a collection of new streets.

The creation of Rosebery Avenue in 1889–91 and subsequent rebuilding effectively destroyed this continuity, of which the only obvious relics today are the interrupted lines of Pine Street-Easton Street, Spafield Street-Yardley Street and Tysoe Street. The survival of Wilmington Square, and the building of much public housing, means that the area north of Rosebery Avenue is predominantly residential, belonging in its general character with that whole tranche of northern Clerkenwell between King's Cross Road and upper St John Street.

In contrast, the Exmouth Market area today is both mixed in character and more tightly defined, especially on the north and west where Rosebery Avenue and Farringdon Road are major topographical divides. It contains two of Clerkenwell's outstanding architectural monuments: Tecton's Finsbury Health Centre of 1935–8, in Pine Street, and J. D. Sedding's Church of the Holy Redeemer, in Exmouth Market, opened in 1888. Also here is the principal historic records office for London, the London Metropolitan Archives in Northampton Road. Exmouth Market is the most important and characterful street here, and the only one to preserve the scale and a significant amount of building fabric from its first development, begun in the 1760s. It is now largely pedestrianized, as is Pine Street, and a general absence of vehicles is one of the characteristics of this entire area. South of Exmouth Market, in and around Northampton Road, twentieth-century redevelopment has left a mixture of municipal and formerly industrial building, all of it lowrise and with much open space.

The following account starts with some investigation of the several spas and pleasure grounds in this area prior to systematic development, before dealing with the later history of one of these sites: the Spa Fields Pantheon and its gardens, later an infamous private burial ground and now part of Spa Fields Gardens. This is followed by accounts of the individual streets and their buildings: Exmouth Market, the north side of Bowling Green Lane, Northampton Road and finally Pine Street.

Spas and other places of resort

Spas, tea gardens and all manner of places for pleasure and recreation once characterized Clerkenwell (see page 2), and here there was a particular concentration from the early seventeenth century, peaking around 1740 and dying out by 1800. Through this period there was a shift from basic outdoor pursuits, on ground and water, to indoor diversions that appealed to more developed tastes. The entertainments were largely associated with the leisure time of London's working population. Others, therefore, held them in low esteem.

By 1676 there were three bowling greens on the north side of the roadway that has become Bowling Green Lane and Corporation Row, opposite a bear garden, a prison (Clerkenwell Bridewell) and a workhouse. (For the south side of Bowling Green Lane see volume xlvi, Chapter I). At least one of these 'greens' was in fact a 'bare', laid out with gravel rather than turf. (fn. 3) On the west side of Bridewell Walk (now the east arm of Northampton Road) there were two public houses linked to these greens. One, close to the site of its successor (Nos 33–39 Northampton Road), was known as the Red Lion by 1720, and had a pit for cockfighting; the other, to the south and perhaps a later arrival, was the Mason's Arms. Around 1750 Thomas Brayne, a stonemason, held this, with a yard and the bowling green behind. In 1759 the property passed to his son, Joseph, who was to figure large in subsequent development. (fn. 4)

Beyond the bowling greens, on what is now Spa Fields Gardens, were ducking ponds, used from at least the midseventeenth century for the popular sport of setting dogs on to ducks. These ponds, one large and the other small, may have replaced the ducking pond displaced by New River Head in 1613 (see Chapter VI). They were in the grounds of an isolated public house (on the site of No. 26 Exmouth Market) known as the Dog and Duck or Ducking Pond House, which faced a footpath and Spa Fields (Ill. 48; see also Ills 208, 215, pages 165, 171). (fn. 5) Around 1730 Benjamin Wicks, a vintner, improved these grounds, making a single large rectangular ducking pond amid gardens, arbours and orchards (Ill. 50). In 1756 Thomas Rosoman, owner-manager of Sadler's Wells Theatre, took a 99-year lease of the premises, undertaking to replace the buildings. The new Dog and Duck was a substantial brick house (see Ill. 52), and the grounds behind, incorporating a skittle ground, were maintained as 'Rosoman's Gardens' throughout the 1760s. The path in front (what is now Exmouth Market) was occasionally used for horse and donkey racing as part of the venue for the Whitsun Welsh or Gooseberry Fair. (fn. 6)

London Spaw

48. View from Spa Fields looking south-east by Wenceslaus Hollar, 1665, with Old St Paul's in background. The Dog and Duck to right, and the Fountain (later the London Spaw) at far left

49. 'East view of the London Spaw', 1731

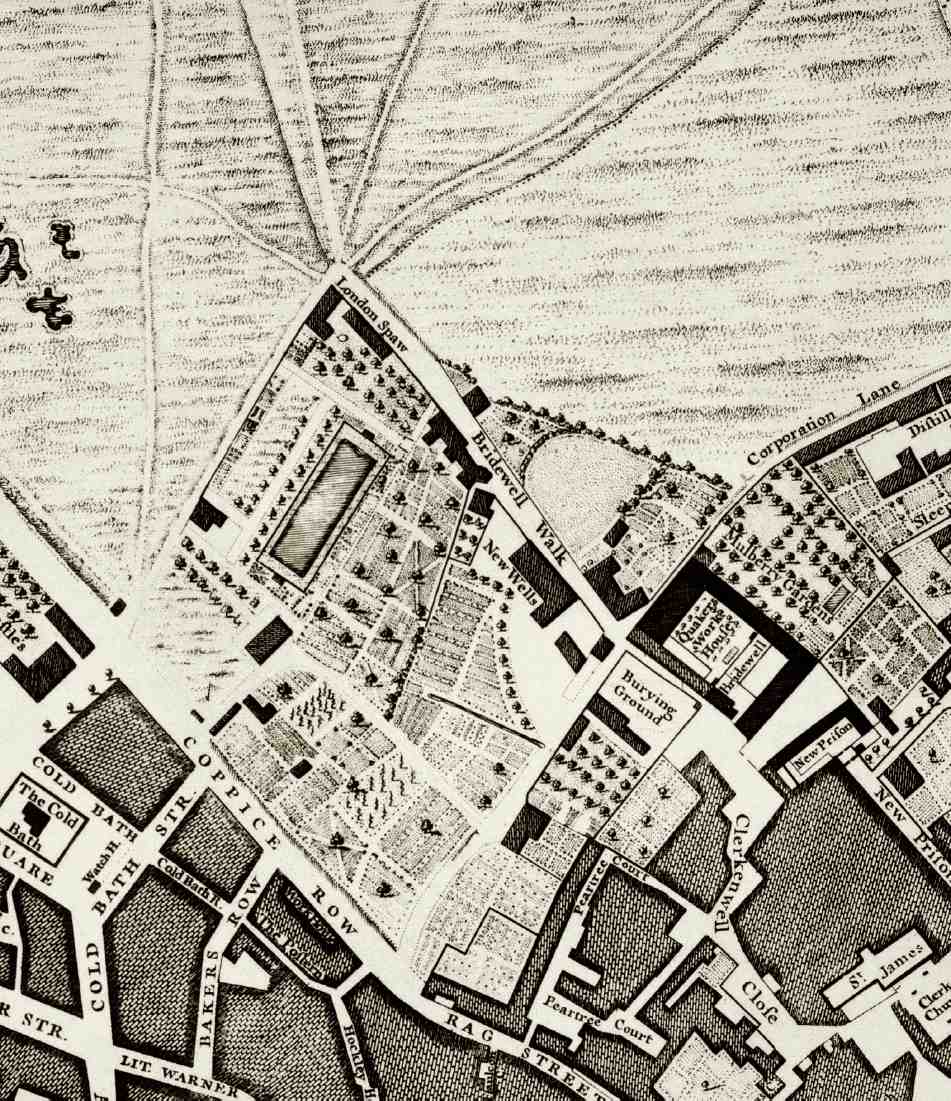

50. Exmouth Market area. Excerpt from Rocque's map of 1746

To the north-east, where this path met Bridewell Walk and

other paths that fanned out to the north and east, the

London Spaw (so spelt until the nineteenth century) commanded a junction, as its successor (see No. 70 Exmouth

Market, below) still does. This establishment is said to

have early thirteenth-century origins as a place dispensing

chalybeate waters. A timber public house, there by the

1660s, was known as the Fountain (Ills 48, 49). The name

London Spaw was adopted in July 1685 by John Halhed,

the vintner and victualler who was then the proprietor,

allegedly with support from the scientist Robert Boyle

who, it was claimed, had found the water in the well immediately below this building to be the best of the locally discovered 'medicinal iron waters'. (fn. 7) The designation was

perhaps intended as a contrast to the newly discovered

Islington Spa (New Tunbridge Wells) and Sadler's Wells

(see Chapters III and V), to emphasise relative accessibility from the metropolis; indeed, as a foreign tourist

observed in 1693, 'Cette maison est la première où la ville

commence'. (fn. 8) There was another skittle ground, and, by

way of further attraction, the garden was made an

orchard, and the water was given to the poor without

charge. (fn. 9) London Spaw enjoyed success as a popular resort,

and in 1733 it was written:

Now sweethearts with their sweethearts go

To Islington or London Spaw,

Some go but just to drink the water,

Some for the ale which they like better. (fn. 10)

51. The London Spa, at corner of Exmouth Street (right) and Rosoman Street (left). Watercolour by J. P. Emslie, 1897, shortly before demolition

The London Spaw was rebuilt in brick in 1766–8, by John Wilkinson, its proprietor, with John Cole, a Whitecross Street bricklayer, and John Horn, another bricklayer who became a victualler and ran the establishment thereafter. It continued to incorporate a skittle ground, and was used by the Northampton Estate as its local base, for the collection of rents and other estate management. The spring dried up in the early years of the nineteenth century, but the alehouse endured. (fn. 11) It was rebuilt again in 1835, by Richard Erlam who enlarged it westwards (Ill. 51). (fn. 12)

New Wells

The early 1730s were the heyday of Islington Spa, when the patronage of Princesses Amelia and Caroline gave a new cachet to the area's sometime disreputable entertainments, and new investment was attracted. Dr Joseph Hooke, a St Pancras physician, opened the New Wells in 1735, in Bridewell Walk on what had been the Red Lion Bowling Green, the present-day site of Finsbury Business Centre (Ill. 50). On a 21-year lease he built an 'Interlude House' (that is, a theatre, interludes being popular comical or farcical stage plays) to compete with Sadler's Wells; there may never have been any waters here. Hooke appears to have encountered difficulties in 1737–8, probably falling foul of the prohibitions on theatrical performance imposed by the Licensing Act of 1737, and quit the site in 1739. (fn. 13) The theatre's most celebrated entertainment, in 1738, was 'A Hint to the Theatres; or Merlin in Labour, with the Birth, Adventures, Execution and restoration of Harlequin', a satirical dig at Walpole (Merlin) and the 1737 Act. In later years there was also a small zoo, with exhibits that included a crocodile and rattlesnakes, and a 'Merlin's Cave' was added to the gardens. From 1737 Hooke (no longer a doctor but a victualler) also held the public house in northern Spa Fields known as Merlin's Cave (see page 240). (fn. 14)

By 1744 Thomas Rosoman had become the manager of the New Wells, which continued to host a lively mix of low and infamously disorderly diversions: topical song, tumbling, 'Grand Dances (both Serious and Comic)', and a concluding pantomime with Rosoman as Harlequin, his most famous role. In 1745 there was an acrobatic giant, a tightrope-walking 7 ft 4in. fifteen-year-old. Rosoman moved on to Sadler's Wells in 1746 and the New Wells closed in 1747, save for a short-lived revival in 1750 under Thomas Yates, who ran the Red Lion adjoining to the north. The theatre was converted for use as a Wesleyan tabernacle in 1752, but had been demolished by 1756 for the building of Rosoman's Row (see below). (fn. 15)

Spa Fields Pantheon

The Spa Fields Pantheon was the most ambitious of Clerkenwell's various pleasure pavilions, and a noteworthy structure of which too little is known. It was built in 1769 on part of the gardens at the Dog and Duck, run since the mid-1750s by the theatre-manager and developer Thomas Rosoman, and followed the rebuilding of both Sadler's Wells Theatre (by Rosoman), and the London Spaw. The Pantheon opened early in 1770 as a 'Tea Drinking House for the Entertainment of Company', under the management of, and ostensibly built by, William Craven, victualler, on a 21-year lease from Rosoman. (fn. 16) It was said to have cost 'upwards of £6,000', (fn. 17) and while the source of this capital is unknown, involvement on the part of the wealthy Rosoman might be supposed. Craven's lease was witnessed by Joseph Brayne, a stonemason who had recently built houses on Rosoman's ground east of the Dock and Duck (see Nos 28–44 Exmouth Market, below).

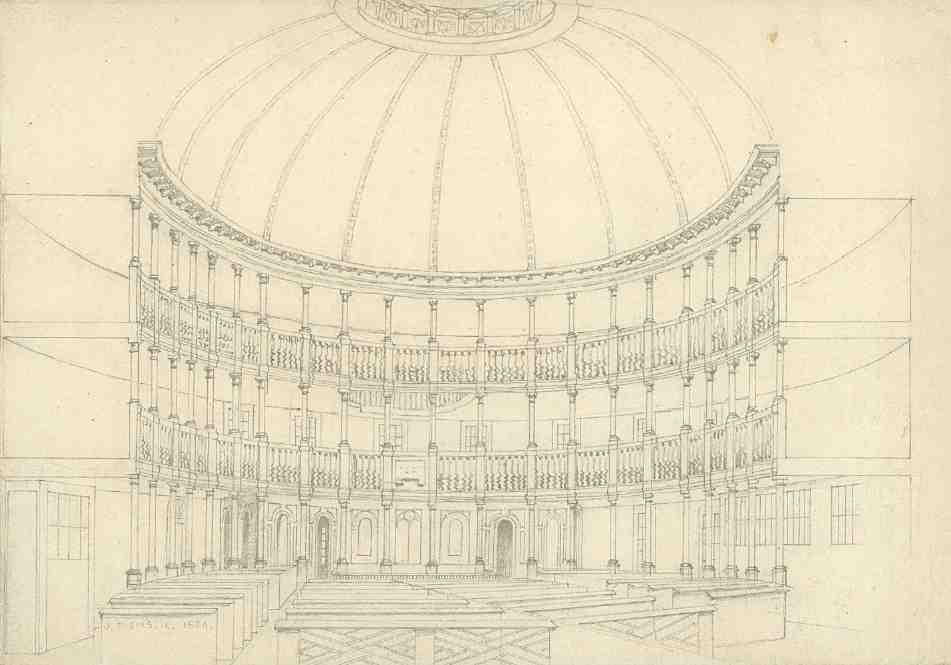

The Pantheon was a substantial domed drum (Ills 52–54). (fn. 18) In function, date and name it was a parallel to James Wyatt's Oxford Street Pantheon of 1769–72. Its form, all but purely circular, was more comparable to that of the earlier Ranelagh Rotunda, and it was sometimes referred to as a rotunda. Externally it was not greatly prepossessing. It had semi-circular projections to front and back, for entrance porches and staircases, the front one with battlements. There were antique busts or vases round the cornice, and atop the dome was a trumpeting figure of Fame. Inside, by contrast, the building had unity, with proportions that C. R. Cockerell admired as 'remarkably agreeable', finding that 'the way in which the cornice and dome meet the eye … is something very delightful'. (fn. 19) Pinks called the interior 'most imposing' and 'extremely chaste and elegant'. (fn. 20) It was essentially a theatre in the round, with two continuous tiers of balustraded galleries overlooking a central floor of 50 ft diameter under a ribbed dome that rose to a height of 80 ft. Three tiers of superimposed Classical columns, thirty-two at each level, supported the galleries and dome. Record drawings made prior to demolition show these as having been of 4in. diameter, and alternately free-standing and attached to reinforcing piers on the outside of the circle (Ill. 54). (fn. 21) The form and dimensions of these columns, and the colouring in one of the drawings, are strongly suggestive of iron, though they are not specifically labelled as such, while other columns in the building are. Nor is it entirely clear that the tiered columns were part of the original construction. Records of alterations made to the building do not mention them, however, and such expensive work seems unlikely in view of the short-term tenure of the building. If they were indeed iron, and original, this would have been an early and startling use of structural cast iron. A few church galleries of the 1770s were supported on such columns, but this would represent a bold use of superimposed iron columns not otherwise known to have been adopted before Henry Holland's Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, of the early 1790s.

52. Spa Fields Pantheon. In 1783, following conversion to use as a chapel. The house to the left was previously the Dog and Duck, rebuilt in 1756

53, 54. Spa Fields Panthoen. Interior view, plan and constructional detail made prior to demolition in 1886

The dome presents a comparably tantalising glimpse of constructional innovation. Its framing, it seemed to Cockerell, included '6 kicks or purlins bolted in [the] centre of each compartment', (fn. 22) and presumably jointed into the sixteen ribs or principal rafters. Evidently all curved, these members must have been made of timber, and relatively lightweight. It is not known how this was achieved, but lamination has been suggested. (fn. 23) This, too, would be without known British precedent, but might have been managed as short sections of planks pegged together, on the lines of a system invented by Philibert de l'Orme and revived in Paris in the 1760s. (fn. 24)

An architect for the Pantheon has not been identified, but William Newton can be suggested as a candidate. Born in Holborn, Newton had been apprenticed to William Jones, the designer of the Ranelagh Rotunda, of which Newton published an engraving in 1761. His Londonbased career was marked by structural expertise, innovation that included experimentation with iron, an interest in Roman buildings, especially after a visit to Rome in 1766, and a predilection for domed circular spaces. He also wrote and published (Commentaires sur Vitruve) in French. (fn. 25)

The Pantheon appears to have been designed as a theatre, its form dictated more by a desire for good visibility than by the simple requirements of assembly and tea drinking. The extensive galleries, which did have seating, can only have been intended for the viewing of 'performances'. Yet Rosoman would not have wanted theatregoers drawn away from Sadler's Wells, and theatre use was not licensed. This was a complementary kind of theatre where the 'company' was the show. There was organ music, and there were further seats on the floor, ranged around a central chimney-less stove with multiple fireplaces, as at Ranelagh. Early descriptions evince nothing more than a vast and crowded drinking house, where tea, coffee, negus, punch and port were served. In the former Dog and Duck, adjoining, there were 'several genteel tearooms'. Craven also inherited Rosoman's four-acre pleasure garden, and this was comprehensively improved, with the former ducking pond reinvented as a boating canal, sneeringly dismissed as 'about the size of a butcher's tray', (fn. 26) with a summer house and a statue of Hercules at either end, and alcoves and seats around. (fn. 27)

The Pantheon represents the cusp and downward turn of Clerkenwell's pleasure-ground era. Attracting crowds of more than a thousand it enjoyed commercial success, but of a kind that was quickly found disreputable and, in the face of a hostile press, ultimately unsustainable. 'Here, apprentices, journeymen and clerks, dressed to ridiculous extremes, entertain their ladies on Sundays; and, to the utmost of their power, if not beyond their proper power, affect the dissipated manners of their superiors'. (fn. 28) In 1772 a report of loose women ('Pray, Sir, will you treat me with a Dish of Tea?') amid 'Disorder, Riot and Confusion', (fn. 29) was followed by a ban on use of the organ on Sundays. Attempts to raise the tone failed and Craven was bankrupted in 1774. The building was sold to Thomas King, the comic actor who had taken over Sadler's Wells in 1771. (fn. 30) He could not improve the Pantheon's reputation and it closed in 1776.

Spa Fields Chapel

The former Pantheon was briefly used as a depot for the sale of carriages. Then, in 1777, it was taken over by a group of evangelicals called the Clerkenwell Society, who adapted the 'colonnade of profaneness' (fn. 31) for low-church Anglican use and named it Northampton Chapel. Success in attracting worshippers provoked a dispute with the Rev. William Sellon of St James, Clerkenwell, who forced the closure of the unconsecrated building in 1779. Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, who was on the look-out for London premises, intervened and took it on herself, reopening it as Spa Fields Chapel and drawing congregations of up to 2,000. Taking up residence in the adjoining house (the Dog and Duck), she claimed it to be her private chapel. This attempt to outflank opposition having failed, she seceded from the Established Church and in 1783 founded the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion as a separate dissenting denomination. In 1787 she took over the long lease which had been granted in 1780 to Murdo Mackenzie, the carriage salesman who had arrived in 1777, and Stephen Maberley, a currier. Lady Anne Erskine joined her in the house, and was left in charge when the Countess died there in 1791. (fn. 32)

A wealthy and influential congregation thus established itself in an area with a rapidly growing population in which Nonconformity was strong. Early in its life as a chapel the dome-top statue was removed, and around 1805 a lantern was formed. In 1845–6, when the chapel gained its first permanent minister, the entrances and internal lighting were improved, the latter with 'a monster ring of gas jets'. (fn. 33) In 1855, when a new 31-year lease was granted, there were more substantial repairs and alterations, with Thomas William Constantine as architect, and R. D. Lown as builder. Constantine proposed inserting oculi in the dome, but this was not done. The works did include a modest entrance porch and a two-room school to the rear, an earlier schoolroom in the house being displaced by shops. One of the first pupils to use these rooms was the future playwright Arthur Wing Pinero. (fn. 34) A heavy pedimented portico was added in 1867 (Ill. 55), when a red-granite obelisk was erected to the memory of the Countess. (fn. 35) The lease was not renewed, the Marquess of Northampton having promised the site for the church that was to become Holy Redeemer (see below). Adaptation of the former Pantheon for Anglo-Catholic use was, unsurprisingly, rejected, and the building was demolished in 1886. A replacement chapel for the Connexion was built in Wharton Street (see page 288).

55. Spa Fields Chapel in 1886

Spa Fields Burial Ground

With the conversion of the Pantheon to a chapel, the old pleasure grounds attached to it were disused. By about 1787 Mackenzie and Maberley had let it become a private burial ground, unconnected with the chapel itself. Covering two acres, it lay behind a row of houses along the south side of what was to become Exmouth Street, and was soon all but wholly enclosed by more houses (Ill. 56). (fn. 36) Speculative burial grounds like this provided a cheaper alternative to London's overcrowded churchyards, much used by the poor. The Spa Fields ground had taken an estimated 80,000 interments by the early 1840s. In the early years Joseph Naples, a gravedigger, began a noted career here as a body snatcher or 'resurrectionist', robbing graves to meet demand from the anatomy schools. (fn. 37) The former pleasure ground became a hellhole, at which yet more nefarious practices were exposed in 1843, once the question of burials in towns had become a subject of Parliamentary attention. (fn. 38) There were up to forty burials a day, gravestones being moved about to create an impression that parts of the ground were empty (Ill. 57). To accommodate new arrivals, bodies were exhumed nightly, and chopped up and burned with their coffins in a 'bonehouse'. The resulting stench reportedly drove nearby residents who could to move away, others to despair at the health implications. In 1845 the case went before magis trates, with representations led by Robert Watt of No. 40 Exmouth Street (see below). Reuben Room, a gravedigger, spoke of his working practices: 'I have been up to my knees in human flesh by jumping on the bodies so as to cram them into the least possible space at the bottom of the graves'. Dr George Alfred Walker, founder of the Society for the Abolition of Burials in Towns, took up the cause. It was widely publicised and Walker himself published Burial-Ground Incendiarism. The last fire at the Bone-House in the Spa-Fields Golgotha, or the minute anatomy of Gravedigging in London in 1846. Charles Bird, the manager, pleaded guilty to one charge and was replaced, but the establishment was not forced to close. Legislation was opposed as an infringement on liberty and an inconvenience to the poor, but this case was a stepping-stone towards the closure of 'intramural' town graveyards and the Burial Act of 1852, which set up machinery for the establishment of new burial grounds in London under the control of local Burial Boards. (fn. 39)

56. Exmouth Market area, extract from Thomas Hornor's Plan of the Parish of Clerkenwell, 1813

The burial ground was closed in 1853. By the 1860s gravestones had been removed and a 'make-belief garden' formed, but the plants died. (fn. 40) For several years the Vestry struggled to find a location for a mortuary, until 1876 when the 3rd Marquess of Northampton permitted this facility to be placed along the south side of the former burial ground (see Ill. 58), provided it was 'somewhat more ornamental than is usual with such structures'—he intended laying out a recreation ground. H. Saxon Snell was the architect, and James Patten the builder, of a low Italianate building with twin dead-houses linked by a veranda and a disinfecting chamber under a cistern in an east tower (Ills 59, 80). The Vestry was pleased with the mortuary, judging it 'second to none in the metropolis'. It was later used as Finsbury Council's cleansing station. (fn. 41)

57. Spa Fields Burial Ground in 1845

Spa Fields Gardens

The intended adaptation of the burial ground as a public open space became possible through the formation of the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association in 1883 and passage of the Disused Burial Grounds Act in 1884. (fn. 42) In the context of official criticisms of housing conditions on the Northampton estate, Lord Northampton and the new association collaborated on opening Northampton Square and Wilmington Square gardens to the public. But these were closed to unaccompanied children, and to compensate for this the burial ground was made into a children's playground in 1886. Having drained, levelled and gravelled the site, the association provided 'gymnastic apparatus' (Ill. 59), an early instance of such outdoor public provision in London, and a drinking fountain, which is still extant. (fn. 43) The new Spa Fields Play Ground attracted crowds of children, and Charles Booth's social surveyors adjudged it 'a great help to the district'. (fn. 44) A drill hall was erected alongside the mortuary, and the open space was also used as an artillery ground by the Finsbury Rifles and, later, by the Territorial Force Association for the County of London. (fn. 45)

In 1923 the Northampton Estate and Finsbury Council agreed a scheme for enlarging and recasting the playground as a recreation ground and gardens. This was begun in 1936, with the laying out of flowerbeds and paths with a public shelter to the east, and the provision of conveniences, new swings and a slide to the west, near the new Finsbury Health Centre, and the old mortuary (Ill. 80). Following clearances in the 1950s the ground was extended up to Northampton Road and Rosoman Street, and the mortuary was replaced with a tennis court. (fn. 46)

Spa Fields Gardens, as it became, was again recast and refurnished in 2006–7, with new landscaping, including undulating 'ridge and furrow' hillocks and grapevine pergolas, designed by Parklife Ltd for Islington Council and EC1 New Deal for Communities. A pyramidal structure comprising a community room, park-keeper's store and toilet, and ranger's office above, is being built at the time of writing (2007). Described as a 'hut', it has been designed by Studio Idealyc and erected by the Albany Construction Co. (fn. 47) For the extension of Spa Fields Gardens, on the east side of Rosoman Street and Northampton Road, see page 94.

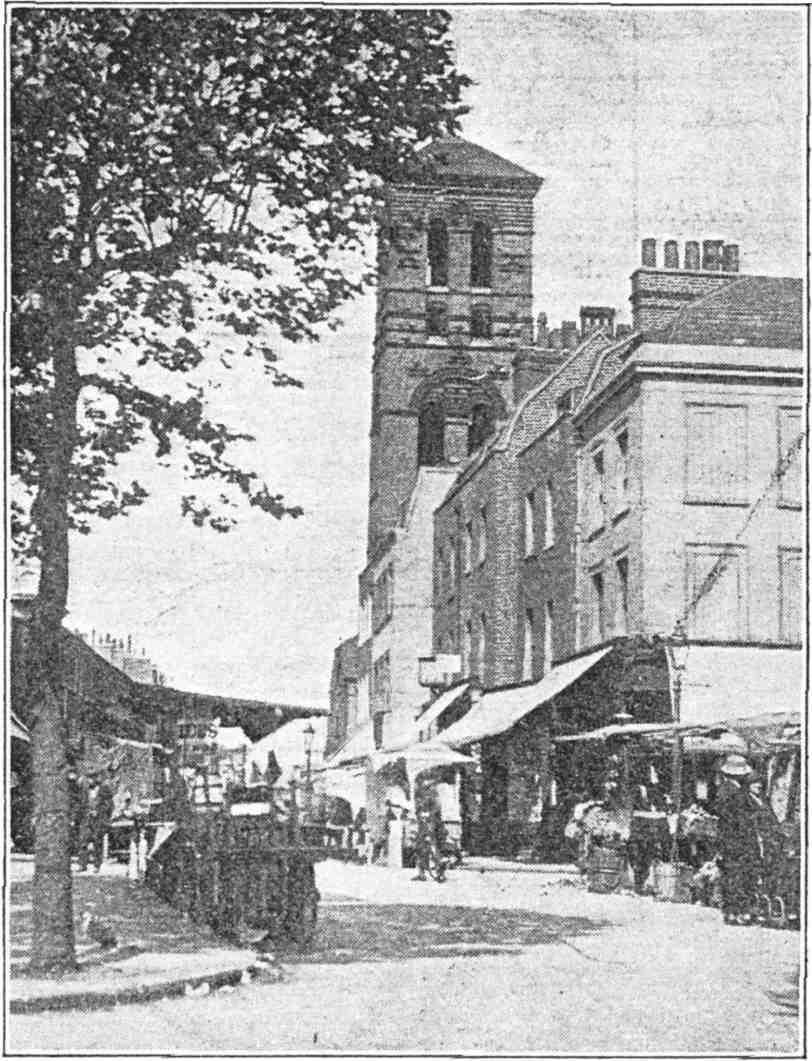

Exmouth Market

Exmouth Market, 'now at the epicentre of trendy Clerkenwell', (fn. 48) is a busy commercial street, the present vitality of which arises from a regeneration project of the 1990s. This followed the decline of the working-class street market that had taken root here in the 1890s, alongside shops that had origins in the early decades of the nineteenth century. The street's development history is complex, with distinct stories for the south and north sides.

It begins on the south side with Thomas Rosoman's 99-year lease in 1756 of the Dog and Duck property (No. 26), which had 325 ft of frontage to the north. Joseph Brayne, the stonemason who may in the 1750s have been involved in the building of Rosoman's Row (see below), took a 90-year lease from Rosoman in 1763, and developed most of the frontage east of the tavern. Ten substantial houses (Nos 28–46) were up by 1766, and immediately became known as Brayne's Row (not to be confused with Baynes Row to the west). These all faced an open field, along with other new buildings to the east, at Nos 56 and 58 of 1765–6, the London Spaw, rebuilt on the corner in 1766–8, and four houses of 1768–9 on the site of Nos 64–68, built along with four others round the corner facing Rosoman Street. To the rear, smaller houses followed along Northampton Row about 1771 (Ill. 56). (fn. 49)

58. Exmouth Market area c. 1894

To the west the first buildings on the sites of Nos 2–22 were known for a time as Spa Place. The Exmouth House site (Nos 12–22) was first built up in the 1780s (Ill. 60), as was Chapel Street (later Chapel Row), by a consortium of tradesmen led by Joseph Wood, carpenter, of St Sepulchre. (fn. 50) The site of Nos 4–10 Exmouth Market was developed in 1789–90 by Samuel Gray, builder, and redevelopment of the western corner by Richard Parker, a City carpenter, followed in the 1790s. His buildings replaced, and were set back from the line of, a turnpike house on Coppice Row (Farringdon Road). (fn. 51)

59. Spa Fields Play Ground, c. 1890, with the Clerkenwell mortuary behind

In 1816–21 the north side of the road was laid out and built up as a broadly uniform terrace to create Exmouth Street. Unlike those of Brayne's Row these houses were designed to include shops, needed because this was to be the southern rim of the Northampton Estate's large Spa Fields development of about 400 new houses (see Chapter X). This project was all handled through an overall agreement and lease of 1817, the developer being John Wilson, a plumber and glazier who became a builder and let the ground on underleases. The name of the new street was chosen in 1816 to honour Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth, who won a battle at Algiers that August to enforce a treaty abolishing Christian slavery, returning to England a hero. (fn. 52)

The buildings of 1816–21 that were Nos 1–9 Exmouth Street were demolished in the 1860s for the building of the Metropolitan Railway's eastern tunnel. They were rebuilt in 1872–3, and demolished about 1890 to make way for Rosebery Avenue. Six shop-houses were built as Nos 11–21 Exmouth Street in 1817–19 in a speculation by Thomas Gooch, a Coppice Row watchmaker who had a hand in much of the development of the north side of Exmouth Street. The corner plot occupied by No. 23 Exmouth Street and No. 6 Spafield Street was first built up in 1817–19, with Thomas Wilson of Yardley Street as the builder, working under Gooch. The south end of Yardley Street was renamed Spafield Street in 1936, and No. 6 survives with a late nineteenth-century iron shopfront made to a patent design by F. J. Chambers; several of these were installed in other small shops close by fronting Rosebery Avenue (see page 122). The corner shop-house (No. 23) became the Exmouth Arms beerhouse about 1863 and was subsequently redeveloped. The shop-houses at Nos 25–57 stand largely as built in 1817–21. The three plots at Nos 59–63 Exmouth Market were leased to Gooch in 1816 and built up in 1817–21 along with Nos 5 and 7 Tysoe Street, by John Howard, plumber and glazier. (fn. 53)

The other parts of the Spa Fields development are now separated by Rosebery Avenue, the formation of which took traffic away from Exmouth Street and led to the establishment of the street market to which the presentday name refers (Ills 47, 58). Most of Exmouth Market's Georgian buildings survive, generally with standard tworoom rear-staircase layouts behind 16–17 ft fronts, but with much alteration and piecemeal rebuilding.

Limited redevelopment in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries included new factories and flats above shops, but the most prominent change was the replacement of Spa Fields Chapel with the Church of the Holy Redeemer.

The small open space at the west end of the street was one of the clearance sites left by the making of Rosebery Avenue. In 1898 the Corporate Property Committee of the London County Council recommended its sale to F. J. Chambers, who had taken on a number of small plots on either side of the road and built shops there (see page 122). (fn. 54) Instead the full council approved a lower offer from the Vestry, which had been trying to acquire the site for several years and now, with financial support from the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association, wished to lay it out as open space with trees and seating (Ill. 61). The banally named 'Plot of Land' was opened with some fanfare in February 1899. (fn. 55)

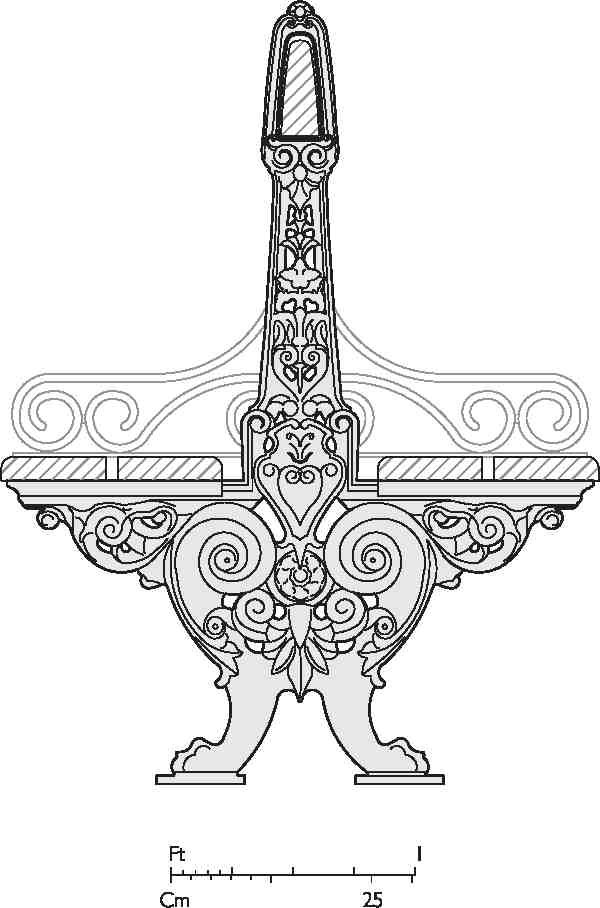

A centrepiece was provided in the shape of a large iron 'refreshment lamp' installed by the Pluto Hot Water Syndicate Ltd. (fn. 56) This lamp-cum-vending machine dispensed, for a halfpenny, a cup of tea, coffee or cocoa, or a quart of boiling water (Ill. 62). It was not, however, a success, being removed in October of the same year. (fn. 57)

60. Exmouth Market in 1931. Nos 12–22 (demolished) to right of tower of Holy Redeemer

South side

No. 2 was built with the Clerkenwell Tavern on the Farringdon Road corner in 1871–3, following the construction of the Metropolitan Railway's eastern tunnel below. This was part of a larger speculation by George Day, a Camden builder, who stayed on to run the public house, which was later extended to incorporate No. 2 (see Survey of London, volume xlvi). No. 4 was rebuilt in the late 1860s, in yellow stock brick with stucco architraves, again in connection with the building of the Metropolitan Railway. (fn. 58)

The red-brick faced block of flats at Nos 6–10 was built in 1903–4 for G. H. Schofield, to designs by C. Bell, Withers & Meredith, architects. It comprises six twobedroom flats, known as City Mansions, with shops below. (fn. 59)

Exmouth House (Nos 12–22) is a large factory quadrangle of 1930–1. A four-storey block faced in red brick, it was speculatively built for R. Dudley, to the designs of Wills & Kaula, architects, by Higgs & Hill Ltd. (fn. 60) Early tenants of upper-storey sections included makers of corsets and loudspeakers and the block always incorporated shops. Sold to Derwent Valley Holdings by the Northampton Estate in the late 1980s, Exmouth House was refurbished and embellished as an office building in 1993–4, through ORMS architects for Colebrook Estates. (fn. 61) It retains a good reconstituted-stone shopfront at its north-west corner (No. 12) where there used to be a bank. The sky-sign comprising the building's name is not an original feature.

61. Bench, Exmouth Market open space

62. Inauguration of the Pluto Hot Water lamp, Exmouth Street, 1899

The nine houses at Nos 28–44 were built following Joseph Brayne's 1763 lease from Thomas Rosoman; a plaque on the front of No. 34 reads 'Brayne's Buildings 1765' (Ills 63, 67). They were also known as Brayne's Row. Brayne built these houses with a number of other tradesmen, evidently operating in a consortium, the others taking underleases. His partners included Richard Singleton, bricklayer; George Travell, carpenter, of Holborn; and Thomas Weatherill, plasterer. (fn. 62) These were originally flat-fronted eight-room houses, of three storeys with basements. They were built with angle fireplaces to the rear, as in the street's other surviving houses of the 1760s (Ills 64, 65). No. 28 retains a plat band between its upper storeys, returned on its flank wall to Spa Fields Lane, but its stuccoed front has had its windows enlarged, for margin-glazed sashes. All the other fronts, save No. 34, which has also been stuccoed, have been rebuilt, No. 30 probably in 1913, No. 32 perhaps c. 1980. There has also been rebuilding to the rear, and mansard attics have been added on Nos 34–40: at No. 34 perhaps by and for John Dore in 1836, and since recontructed; at No. 38 in 1889; and at No. 36 since 1991. Nos 42 and 44 appear to have been completely rebuilt. (fn. 63)

No. 46 is the earliest surviving building in Exmouth Market. It stands forward from, is bigger than and marginally antedates Brayne's Row. It was built in 1763 following a lease in March of that year from Rosoman to Richard Ambler, a Clerkenwell gentleman, who was the first occupant. His property had a 47 ft frontage that included the site of Nos 48 and 50. This allowed the house, otherwise laid out like the row's other houses of the 1760s, to have a villa-like full-height canted bay on its east side, for a winder staircase (Ill. 64). (fn. 64) This was cut down and replaced in 2000–1 when the upper storeys were converted to flats, linked to No. 48, and an attic floor added; the work was overseen by Carden & Godfrey, architects. (fn. 65)

63. Exmouth Market looking west in 1968. Nos 28–60 (right to left) in background

64, 65. First-floor plans of No. 46 (left) and Nos 56 and 58 Exmouth Market, as built

Greatly divergent in building lines and heights, Nos 48–54 are later Georgian infill between houses of the 1760s. No. 54 was built in 1792, as a low three-storey house with a steeply pitched gambrel roof to the rear. Nos 48 and 50 were added in 1833–4, and, unlike their neighbours, probably always incorporated shops, No. 48 having only two storeys with garrets and No. 50 taking essentially the same form as the nearby houses of seventy years earlier. A late eighteenth-century 'cottage', set well back behind Nos 48 and 50, survived until the 1860s when its access passage was blocked with the two-storey extension to No. 54 that is now No. 52. (fn. 66)

Nos 56 and 58 (Ill. 65) were built as a pair in 1765–6 by John Wilkinson, the victualler who redeveloped the London Spaw in 1766–8. He was the first occupant of No. 58. (fn. 67) These houses were a bit larger than those of Brayne's Row, with four full storeys and 18 ft fronts. No. 56 retains its original closed-string staircase, with robust vase balusters. In the early nineteenth century the first-floor windows were cut down for the present larger sashes, work perhaps done for Joseph Grimaldi (see below). The upper parts of the front wall and the east parts of the back wall were rebuilt in 1925, and No. 58 has been wholly refronted. No. 60 was built about 1780 as one of a pair with No. 62. Its front wall was rebuilt in 1927. (fn. 68)

66. The former London Spa in 2006

67. Nos 34–56 Exmouth Market in 2006

Nos 62–70, together with Nos 69 and 71 Rosoman Street are a single development of 1898, the last incarnation of the London Spa (see above). The whole of this corner property was then given its present form by Henry Hobson Finch, proprietor of the public house (Ill. 66). This was a bold improvement in an attractive Wrenaissance idiom, by the architects W. A. Aickman and J. K. Bateman, in red brick with ample dressings, including heavy moulded cornices and a pilastered green faience ground storey. The group's mass is twice broken, by a step down in height at No. 71 Rosoman Street, and by a passage between Nos 62 and 64 Exmouth Market. This large public house continued to incorporate the Northampton Estate's 'audit rooms'. (fn. 69) The London Spa name was lost in 2002 when the pub became a restaurant, though six flats above are still known as London Spa Court.

Nos 63–67 Rosoman Street is a factory block of 1933–4, built by Henry Kent Ltd for Edward Delfosse, whose Ormond Engineering Co. Ltd, manufacturers of screws and radio components, had several other lightengineering premises in north Clerkenwell. It has a vertically glazed stair bay to the north and a deep four-bay return to Rosoman Place. (fn. 70) In the 1990s the building was converted by Magri Developments to Spa Heights, loftstyle apartments. (fn. 71) Adjoining to the west is No. 2 Rosoman Place, also built in 1933–4 for the Ormond Engineering Co., probably as offices, though it appears as a two-bay three-storey house in an odd early nineteenth-century manner. (fn. 72) No. 1 Rosoman Place is another brick-faced four-storey factory, built in 1903–4 when it formed part of Northampton Row, for William Arthur Fincham & Co., fancy-box makers, with H. Yolland Boreham as architect, and Sabey & Son as builders. (fn. 73) It has been converted to office use.

North side

The island block comprising Nos 11–21 Exmouth Street and Nos 46–54 Rosebery Avenue was redeveloped in 1929–30 as four-storey red-brick-faced factory and shop premises, for which Herbert A. Wright was architect, and A. Class & Son the builders. (fn. 74)

No. 23, the Exmouth Arms, was rebuilt in a neoGeorgian style for the Camden Brewery Co. in 1915–16, by the Bedfordshire builders S. Redhouse & Son (Ill. 68). The large lettered green-tile panel on the canted corner was altered following a takeover by Courage, perhaps in 1935. (fn. 75)

Nos 25–41 make up the western part of a long flatfronted terrace. This was built in 1817–21 under John Wilson and Thomas Gooch in two takes, the larger one comprising Nos 29–41. Josiah Trustrum, a City carpenter, was responsible for Nos 29–35 and involved with Nos 25 and 27. He also completed Nos 37 and 41, which James Norris, a local builder, had begun. No. 39 was built by John Sanguine, an Aldersgate carpenter. (fn. 76) No. 29 has been relatively little altered, and some early twelve-pane sash windows survive on the first floor at No. 35. Nos 25 and 27 and 37–39 have been wholly re-fronted, the latter in 1924 when they were made a single property. (fn. 77)

The main eastern section of the terrace, at Nos 43–57 (Ill. 69), was built simultaneously, in 1817–20, and as broadly uniform, under George Goodwin Esq, of Chapel Street, Grosvenor Place. (fn. 78) No. 45 was finished after the others, in 1821, by James Fisher, a carpenter of Tabernacle Row. Who built the others is not known. Nos 45–49 and 57 have relatively little-altered brick fronts, while Nos 43 and 51–55 have long been stuccoed, though only recently painted in bright colours. Only Nos 45–51 have attics, recently remade and enlarged. No. 55 had to be repaired in 1918 following air-raid damage. (fn. 79)

68. The Exmouth Arms, No. 23 Exmouth Market, in 2006

Nos 59 and 61 were rebuilt in 1924 for David Greig, the chain-grocer, to simple neo-Georgian designs from his firm's architects' department, headed by P. Woollatt Home. The builders were J. Greenwood Ltd. The premises were branded with a ceramic plaque and with thistles on the facia consoles. No. 63 was rebuilt in 1912 as a humble two-storey butcher's shop. (fn. 80)

The triangular corner plot occupied by Nos 65–69 was developed in 1818–19 with three houses, two facing Tysoe Street (formerly Nos 1 and 3), with a yard to Exmouth Street. John Breeze, a carpenter of Pollen Street, Hanover Square, was the builder. (fn. 81) The slightly bowed corner here relates to a circus proposed for this junction by the Northampton Estate surveyor, S. P. Cockerell (see page 243). (fn. 82) Nos 65 and 67 are infill of the yard from 1831–2, and may never have been more than two low storeys. (fn. 83)

Nos 1–7 Tysoe Street adjoining is a red-brick factory of 1919–20, built by William Downs Ltd for Comoy & Co., briar-pipe makers, as an extension to their premises at Nos 72–82 Rosebery Avenue. It was converted to 'live/work' apartments by Galliard Homes in 2000–1. (fn. 84) Across the junction the triangular corner site at Nos 2–4 Tysoe Street was redeveloped in 1930–1 for Kerr's Bakeries, with G. H. Carter Ltd as builders. (fn. 85)

69. Nos 41–61 Exmouth Market in 2006

Early occupants

When new in the 1760s, Brayne's Row had views across the fields to the north, and was seemingly in prosperous singlefamily occupation. Isaac Mainwaring, a saw-maker of some substance (see page 89) and an early chairman of the Clerkenwell Society at what became Spa Fields Chapel, was among the first residents, at what is now No. 30 Exmouth Market. A number of artists established themselves here, perhaps selling from their ground-floor rooms, though they did not have shopfronts. By 1775 James Slade, a painter, was in No. 38 where in 1781 Robert Pollard, an engraver and print seller, followed, setting up 'one of the most versatile and enterprising studios in town'. (fn. 86) Pollard moved to No. 58 in about 1790, where he continued until 1810. His youngest son, James Pollard, who gained eminence as a coaching and sporting artist, was born in Brayne's Row in 1792. No. 62 was occupied by another well-known engraver, Richard Earlom, from about 1800, when he took the premises from his father, William Earlom, up to his death in 1822. From c. 1795 No. 40 was occupied by John Caley, an antiquary and archivist of public records. His house contained a significant library and drawings collection, as well as many important historic manuscripts and indices, functioning as a kind of public record office subject to Caley's granting access. He expanded into No. 42 in the early 1820s, and died at No. 40 in 1834. (fn. 87)

Joseph Grimaldi, the actor and original pantomime clown, moved into this somewhat artistic milieu in 1818, to No. 56, where he remained until 1828. He arrived when the immediate area's entertainment character had gone, and as the land to the north was being laid out as a sober suburb. But Grimaldi had local roots, his career following that of his father. He performed regularly at Sadler's Wells as a child in the 1780s and 90s, lived in Penton Place (c. 1794–9), at No. 44 Penton Street (1799–1800), and after the death of his wife, at No. 4 Baynes Row. He later moved away from the area, but returned to Sadler's Wells in 1818, having bought a share in the theatre. Disability forced him to stop performing in 1825. His last residence in 1835–7 was also local, at No. 22 Calshot Street. In 1938 the London County Council, failing to identify the Exmouth Market house, commemorated him with a plaque on the Calshot Street house, demolished in 1960. The present blue plaque at No. 56 Exmouth Market was put up by English Heritage in 1989. (fn. 88)

Shops and the street market

From 1819 the newly formed Exmouth Street became a shopping centre. The first purpose-built shops here were on the north side of the street, and served mainly the new area then building to the north. Because of their function these houses lacked the forecourts that buffered the shopless houses of Brayne's Row. A chemist and surgeon occupied the corner shop at No. 23 from 1819, while among other first occupants were a cabinet-maker (No. 27), a broker cum carpenter and turner (No. 53), and a shoemaker (No. 63). Among early specialist tradesmen were the bookbinders Euphan and Archibald Leighton, soon E. Leighton & Son, subsequently in the 1840s Leighton & Eeles. Starting at No. 47 from 1819 and quickly expanding into No. 45, they were among the first firms to market cloth for bookbinding. In 1847–9 Austin Holyoake, the radical printer and publisher, took over No. 47, from where he produced The Reasoner. (fn. 89) Other specialists present by the 1840s included Galley & Co., barometer and looking-glass makers, at No. 37. There were also carvers and gilders at Nos 31 and 53, and a lapidary at No. 57. Many of these north-side houses soon developed workshops on their small gardens. (fn. 90)

Retailing on the north side of Exmouth Street led to changes in occupancy opposite. By 1825 No. 22 was a 'capital grocer's shop'. (fn. 91) Shops began to appear on the Brayne's Row forecourts from about the early 1830s, when Nos 48 and 50 filled in the last gap on the south side with houses probably incorporating shops. Robert Watt, variously described as a silversmith, jeweller, watchmaker, pawnbroker and general salesman, took No. 40 after the antiquary Caley's death in 1834 and built over the forecourt. Skilled trades concentrated in the Brayne's Row houses, between ordinary shops in the smaller properties at either end of the street. Around 1840 trades on this side included: jeweller (No. 28), plumber and zinc worker (No. 34); lapidary (No. 36); pen maker (No. 38); artist (No. 46); brass founder (No. 54); and carpenter and builder (No. 60). Some gentility still hung on then, but by 1848 No. 56, apparently the street's last singly occupied house without a shop, had been taken by John Rushbrook, a tailor. It had been broken into four households by 1860. (fn. 92)

By the time the Northampton Estate granted new leases in 1856, all the Brayne's Row forecourts had been built over. New shopfronts appeared in the early 1850s at Nos 31, 36, 38, 40, 50 and 59. Portions of the facias survive at Nos 38 and 40, the latter with 'Medcalf' butcher's-shop lettering, perhaps from a 1928 refitting. (fn. 93) The food and drink trades were in increasing evidence. A pork butcher leased No. 42 from 1855–6, while a cheesemonger took No. 46, which continued as a cheesemonger's into the twentieth century. Catering had begun to extend beyond the public houses, with dining and coffee rooms at Nos 27 and 35 by 1850. In 1860 No. 32 was an 'alamode beef house', No. 55 had become more coffee rooms, and No. 51 was another beer-house, the Morton Arms. By 1870 an Italian confectioner occupied No. 30, and No. 39 was another coffee house in the 1870s. The partly surviving shopfront at No. 58 may date from 1868 when work for William Alpheus Higgs & Co., grocers, was supervised by William Smith, architect. No. 42 housed 23 people in four households in 1881, but this was exceptional, as the houses above the shops were on the whole not particularly densely occupied. Indeed, a shift away from residential use can be dated from 1889 when No. 53 was converted and became an outlet of Home & Colonial Stores, the street's first chain store, without residents on the premises. (fn. 94)

Selling from the pavements had been complained of in the late 1830s, and probably continued intermittently. The formation of Rosebery Avenue aroused opposition from shop-owners, who feared loss of trade if Exmouth Street ceased to be a main traffic route, but were equally against its incorporation into the new road, as this would have entailed the redevelopment of one or other side. Yet the new road made it possible for Exmouth Street to become officially a market street, 'whose character it already has'. (fn. 95) At the request of a ratepayer group the Vestry approved a trial, and costermongers were admitted from July 1892, just after Rosebery Avenue opened to traffic. (fn. 96)

The market flourished for eighty or more years (Ills 60, 63). By 1896 'Trucks and stalls with wares of all kinds lined the narrow road, and there seemed scarcely a square yard without a person on it'. (fn. 97) Geraldine Mitton described Exmouth Street in 1906 as 'one of the market streets of the poor … Stalls of fruit and vegetables, of cat's meat and embroidery, jostle one another'. (fn. 98) A contemporary novel evokes an evening scene here with 'naphtha lamps flaring, the smell of butchers' shops, the pease pudding, gutters full of vegetables'. (fn. 99) The market continued and the street was formally renamed Exmouth Market in 1938.

The lure of the market evidently made the shops more lucrative, attracting further 'multiples'. In 1907 Liptons the tea merchants took Nos 52 and 54. David Greig occupied No. 61 by 1910 as a cheesemonger, and rebuilt Nos 59 and 61 in 1924 as a kind of proto-supermarket. Branches of other chains arrived: Boots (No. 18), Pearks' Dairies (No. 48), the Maypole Dairy (No. 47) and the British Shoe Co. (No. 68) by 1921; with the Midland Bank (No. 12) and F. W. Woolworth (Nos 20–22) following in the 1930s. A few new specialist shops also made their mark. Among them was Brandstater's at Nos 33 and 35, which maintained a wide reputation as a working-class outfitter, specializing in caps, up to the 1960s. The firm dated back to 1902, when Jacob Brandstater established a draper's shop at No. 33. By 1914 the premises had spread to No. 35 and acquired a new shopfront. (fn. 100) No. 46 became a stewed or jellied eel shop in the 1930s. It long remained in the hands of the Manze family, which also had premises in Chapel Market (see page 399) before becoming Clark's Pie & Mash & Eels Shop in 1962. Its interior, little changed today, is a token relic of local working-class culture. (fn. 101)

Decline came sharply in the 1970s to both shops and the street market, where in 1984 there were only six stalls left on about 100 pitches. (fn. 102) Islington Council tried to revive the market in 1986–8 with repaving and a 'relaunch', also aiming to stimulate greater use of empty upper storeys over shops. But the number of vacant properties increased. In 1992, when the street was included in the new Rosebery Avenue Conservation Area, it was said to be 'a squalid and filthy slum'. (fn. 103)

The Northampton Estate having sold off its Clerkenwell freeholds after the Second World War, the Debenham Property Trust became the principal property owner in Exmouth Market. It sponsored a fresh initiative in the early 1990s under the watchword of 'cultural regeneration'. Islington Council became a partner in this effort to reduce the number of empty shops (sixteen in 1996). In a planning policy change of 1996, mixed use was encouraged, especially restaurants and upper-storey flats. New lighting and street furniture modified the streetscape in 1996–7, when pavements were also widened. Despite this the street market finally withered away, causing some local resentment. The project was not explicitly designed to bring about gentrification, but that was the result. (fn. 104)

Among numerous new restaurants, the well-known Moro was an early arrival in 1997. The chains followed, from Pizza Express, since gone, to Starbucks and Subway. Other new shop uses were largely aimed at young, welloff customers. Façades and facias were transformed with brightly coloured stucco and much lower-case lettering (Ill. 69). By 2006 Exmouth Market, 'an awful dump 15 years ago that is now becoming a groovy little shopping street', (fn. 105) could present itself as 'a burgeoning area of fashion and lifestyle boutiques, designer furniture, health and beauty specialists, unique gift shops, interior design and a wide range of exciting cafes, bars and restaurants'. (fn. 106) Against this backdrop, the Exmouth Market Traders' Association initiated a limited revival of the street market on Saturdays.

The following table sets out the changing use of shops in Exmouth Market during the past century.

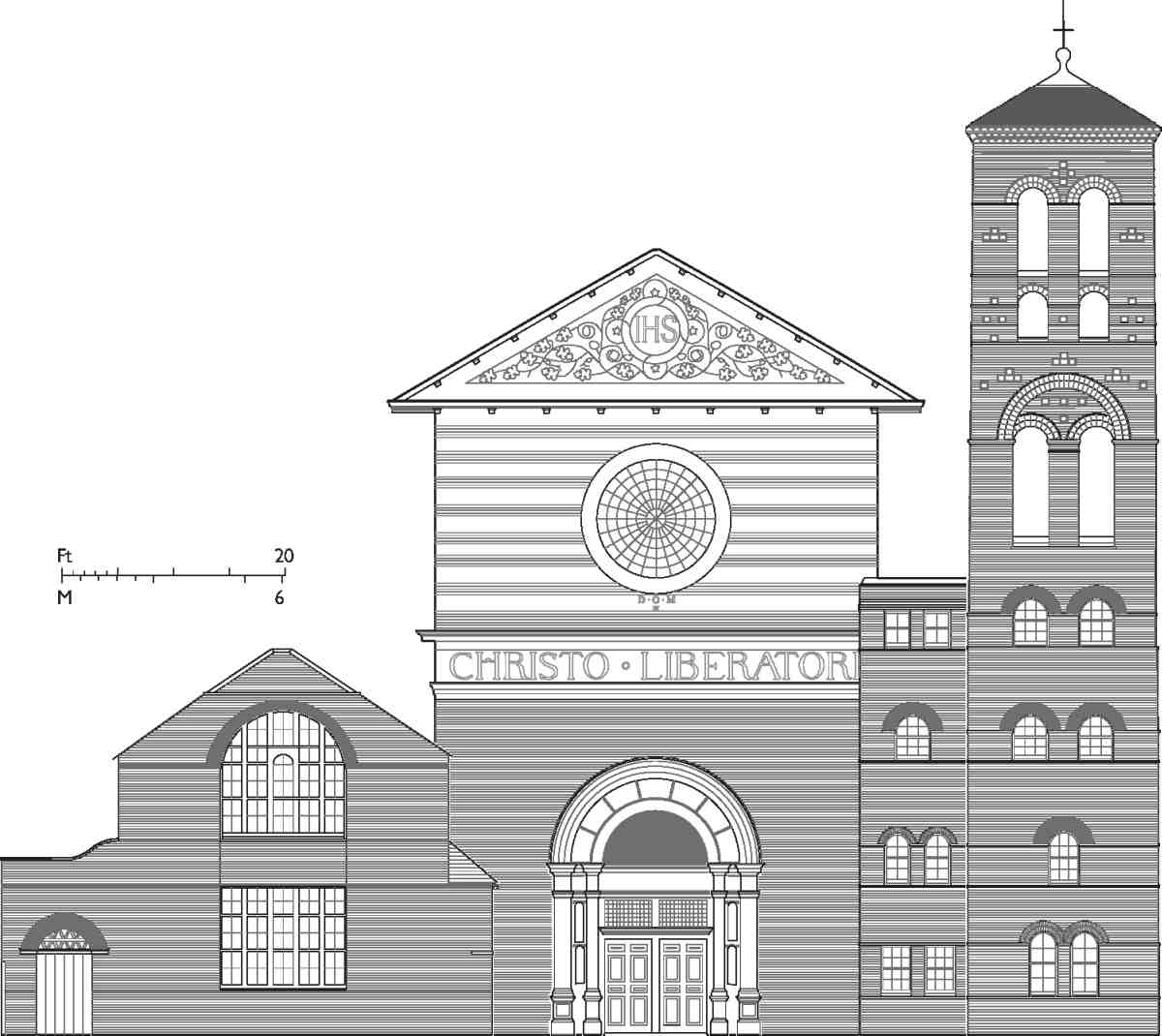

70. Church of Our Most Holy Redeemer. Front elevation, with parish hall (left), clergy house and campanile (right). J. D. Sedding, architect, 1887–91; enlarged by Henry Wilson, architect, 1894–1916

Church of Our Most Holy Redeemer

A notable monument to Anglo-Catholic enthusiasm, this church was designed by J. D. Sedding and started in 1887–8. It remained incomplete until 1894–5 after Sedding's death, when the (liturgically) east end was extended by his former assistant Henry Wilson. The campanile, with the clergy house which forms its lower stages, was a later conception. Built in 1905–6, it too was designed by Wilson, who added the third part of the ensemble, the parish institute of 1915–16, and made a few later additions to the church.

With Holy Redeemer, Sedding put into practice his view that the Italian Renaissance, the 'living, traditional style of Europe', was the style best suited to cramped urban sites, and best able to satisfy the 'craving of the modern mind for vastness, size and space'. (fn. 107) When the design was published (Ill. 71), the architect E. J. Tarver hailed Sedding as 'a convert to the modern school'; and Walter Pater, while clinging to the belief that Gothic would remain the natural style of the sacred, found the new building 'a very successful experiment'. (fn. 108) But William Woodward, an architect who lived not far away in Granville Square, expressed a more conservative view when he called it a 'hideous structure'. (fn. 109)

The parish of Holy Redeemer was created by an Anglo-Catholic faction from St Philip's, Granville Square. Vestments and ritualistic practices had been introduced there in the 1850s by the Rev. Warwick Wroth. In succession to Wroth, Anglo-Catholics became well established in the district, which offered opportunities for missionary work among the poor.

In 1874 a mission was set up in the southern end of St Philip's parish, with premises close to Exmouth Market in John Street (since obliterated by Rosebery Avenue), and later Tysoe Street. The leading figures involved were two curates from St Philip's, first Nathaniel Poyntz and then Edward Vincent Eyre, in due course the first vicar of Holy Redeemer. There was a link between the mission and the Sisters of Bethany, the Anglican nuns whose House of Retreat was close by in Lloyd Square. (fn. 110) From the start, the aim seems to have been to divide the parish. Though Wroth's successor at St Philip's, the Rev. R. H. Clutterbuck, appears initially to have been in favour of setting up a new church he came to see it as a rival. His concern proved wellfounded, for in 1936 St Philip's was closed and the two parishes were reunited under Holy Redeemer.

Church of Our Most Holy Redeemer, Exmouth Market, J. D. Sedding, architect, 1887–91

71. Early design of interior, perspective by Gerald Horsley, 1887

72. View at time of consecration in 1888

73. Detail of baldacchino and capital. F. W. Pomeroy, sculptor, 1888

74. West end in 1994, showing font and organ gallery

With the promise of an endowment from Lucy Nicholson, a benefactress of the Sisters of Bethany closely involved in the new mission, Clutterbuck himself set the ball rolling. In December 1875 the Ecclesiastical Commissioners gave approval to a new district, provisionally named after St Ambrose. After several false starts, the scheme was revived in 1882. By this time Clutterbuck was in open opposition, but his objections were overruled and in June the new district of Holy Redeemer was constituted. (fn. 111) Miss Nicholson was given the right to nominate the first minister, the patronage then passing to a group of High Church associates. Eyre was confirmed as first incumbent. In the meantime, with her financial support, a mission house and chapel had been opened in 1880 at No. 21 Wilmington Square. The chapel, initially dedicated to St Etheldreda but soon renamed Most Holy Redeemer, took on the status of temporary parish church. (fn. 112)

Already controversial locally, the project caused further dissension when the boundary of the new district was redrawn to include Spa Fields Chapel, which was offered by the Marquess of Northampton as a site for the church in May 1884. This took a bite out of the existing district of St James and a petition of local people warned against the 'bitterness and strife' that the new church and its 'extreme High Church' clergy would provoke. (fn. 113)

Fund-raising and design were held up until 1886, when the enlargement was finally approved. By then any idea of adapting Spa Fields Chapel had been discarded. A building committee was set up and Sedding, whose contacts among the promoters and their circle were numerous, was appointed architect.

Prominent on the committee were the leading lay AngloCatholic, the 2nd Viscount Halifax, and Canon Henry Scott Holland, founder of the Christian Social Union. The Dean of St Paul's and the principal of Pusey House in Oxford were also members, as was Capt. F. T. Penton, the Pentonville landowner and Finsbury MP. (fn. 114) Influential in matters of taste seems to have been the treasurer of the building fund, Eyre's friend F. A. D. Noel, who interested himself in Italian architecture and was for many years a parish worker and later non-stipendiary curate.

The nave of Holy Redeemer was built by James Morter of Stratford, at a cost of £10,564 (more than twice the estimate, due in part to the need for deep foundations, as the site proved to be made ground). (fn. 115) The foundation stone was laid by William Gladstone in August 1887, and the new building, with a temporary east wall, as yet sparsely furnished but unequivocally High-Church with its baldacchino, Stations of the Cross and temporary confessional, was consecrated by Bishop Temple on 13 October 1888. (fn. 116)

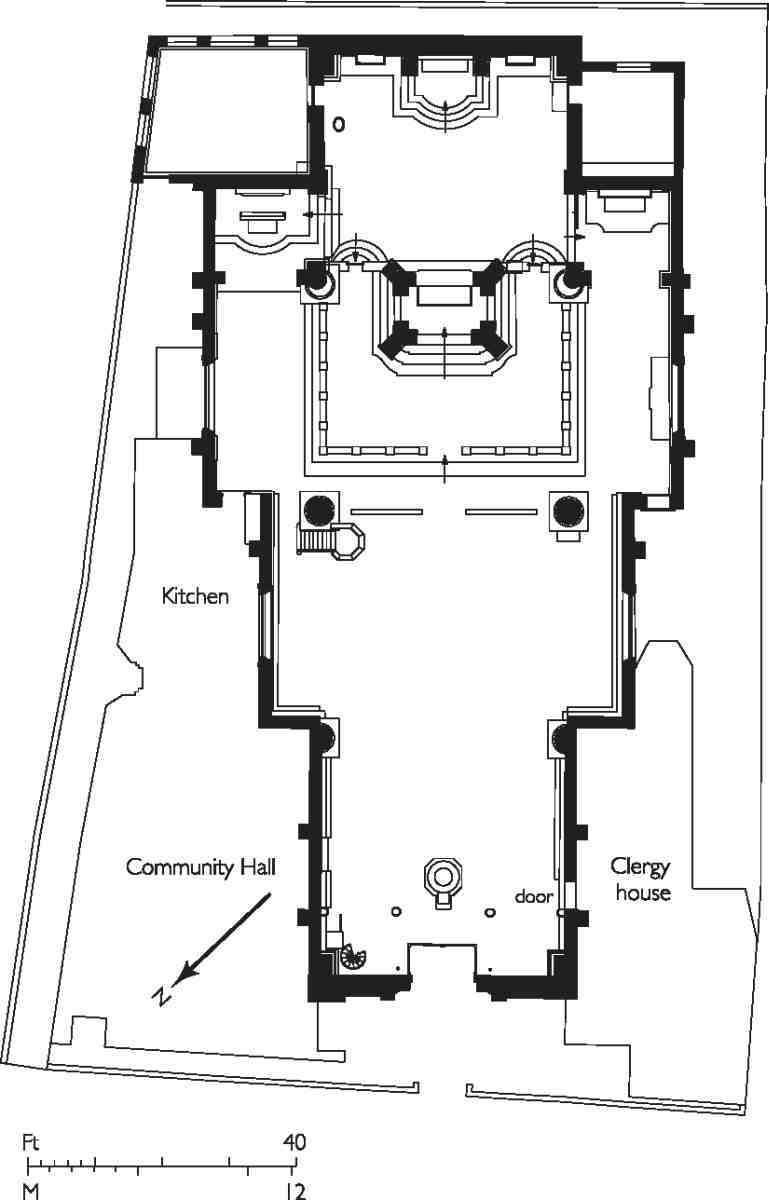

75. Holy Redeemer, plan

The exterior of the church is built largely of London stock brick, with side walls banded in red brick. The front is tall and narrow, with a deep-eaved pediment containing in carved relief the monogram IHS wreathed in trailing vines, and plain Portland stone banding (Ills 70, 76). Across the main cornice is incised christo liberatori, in giant lettering, concluding the legend d(eo) o(ptimo) m(aximo) et begun unobtrusively above. This inscription, conspicuously absent from the earliest published view of the exterior (Ill. 72), was described as a 'recent' addition in 1890. (fn. 117) The entrance is marked by a shallow recess of stone in round-arched, Quattrocento style, infilled with red rubbed bricks.

Inside, there is a small draught-lobby, the upper part of which is original; the glazed doors were installed in 1973. The west gallery for choir and organ, approached by a spiral iron staircase, is also original. (fn. 118) The body of the church consists of four bays divided by giant columns carrying a continuous entablature, from which spring plaster rib-vaults (Ill. 77). According to an Edwardian source the columns and entablature are of concrete encasing steel stanchions and girders, but iron may be more likely at the original date of construction. (fn. 119) The second bays open up into narrow aisles, the third into short transepts. The compression of the essentially cruciform plan (Ill. 75) at the west end left space for parish buildings on either side.

Contemporary and later writers have found affinities with the interiors of several of Wren's City churches. (fn. 120) Whether this was in Sedding's mind, however, is not certain. One hint of Wren's influence in matter of detail is given by the high oak dadoes to the aisles and bases of the giant columns, a treatment used by Wren which had been revived by G. G. Scott junior at St Agnes, Kennington, in the 1870s.

76. Holy Redeemer, view from north in 2004

Other sources for the style of Holy Redeemer are suggested in an appraisal of Sedding's work published not long after his death by his former pupil J. P. Cooper, with Wilson's assistance. This relates how the design for Holy Redeemer originated as an idea for a 'cheap church' Sedding had mentioned to the vicar of St Mary's, Cardiff, Father Griffith Jones, as suitable for a new mission church, probably in 1884. Subsequently he was commissioned to design the new church, St Dyfrig's, Cardiff, producing however a florid late Renaissance scheme, which was rejected and replaced by the Gothic design eventually built. The Clerkenwell church, claimed Cooper, was the rejected scheme 'grown almost beyond recognition, and with the Italian element left out'. On a later visit to Cardiff, Sedding allegedly told Fr Jones that 'I have put up your church of St Dyfrig's at Clerkenwell'. (fn. 121)

There are confusing elements to this story, since Holy Redeemer is both simpler and on the face of it more Italian in spirit than the rejected St Dyfrig's design. (fn. 122) Holy Redeemer does share with that design its plan and the character of its nave colonnade, but perhaps has more in common with the initial 'cheap church' concept. Father Jones had supposedly spoken of his projected church as a 'barn'. In the use of this word there may be an echo of the fourth Earl of Bedford's famous injunction to Inigo Jones concerning St Paul's, Covent Garden. The deep eavespediment at Holy Redeemer does indeed recall that of St Paul's. Before it became cloaked in by other buildings it must have had a rather barn-like look, as it still does seen from across Spa Fields Gardens (Ill. 78).

Three successive designs for the church are said to have been drawn up by Sedding, and though the evolution of the final scheme is uncertain, the result was unquestionably compromised by shortage of funds. According to Sedding's friend, the architect Charles Lynam, 'Everywhere, even outside, there is an evident struggle of mind to achieve a power of expression out of the commonest materials'. In the planning, too, there seems to have been comparable struggle. 'I have a letter from the designer', wrote Lynam, 'in which he states, with remorse, that no one knew the difficulties he experienced in this case'. (fn. 123)

The design exhibited at the Royal Academy and published in 1887 is either the first or the second scheme. Drawn by Sedding's friend Gerald Horsley, the perspective (Ill. 71) shows a lavishness of decorative treatment far removed from the bleak-looking interior of 1888: ashlarfaced walls, banded columns, ornate frescoing on the east wall behind the high altar, and more elaborate furnishings. While the shape of the church shown is essentially as built in 1887–8 and extended by Wilson, there are two significant differences. The fourth bay in the perspective is occupied by the chancel (with the organ and choir stalls to one side), instead of by a separate chapel, and there is a change of level after the first bay, so that the entrance end of the church has more the character of a vestibule or narthex than part of the nave proper. The effect is to increase the dramatic effect of the interior.

By the time the church came to be built this design had been substantially modified. It had been decided that the future fourth bay would be used for a 'morning chapel', and therefore the high altar and baldacchino were from the start in their intended permanent and isolated position, although standing at first against a temporary wall of wood and corrugated iron which was removed on the construction of the fourth bay. (fn. 124) It was presumably for this reason that the choir and organ were banished to a west gallery— a rare arrangement in Anglican churches at that date. (fn. 125)

How Sedding himself envisaged the future arrangement of the fourth bay after the first three had been completed remains unknown. It would have been expected that the church would be embellished in time as funds permitted. To some extent that is what happened: the wainscotting, for instance, was carried out piecemeal over many years, and as late as 1906 the subject of frescoing the walls was still in mind. (fn. 126) Likewise economy presumably dictated the relatively cheap wood-block flooring, anticipating a later and richer treatment. Two important decorative elements in the published scheme were, however, executed at the outset: the elaborate capitals of the nave columns, modelled by the art-sculptor Frederick Pomeroy, and the baldacchino, also with capitals by Pomeroy (Ills 73, 77). (fn. 127)

77. Holy Redeemer, interior in 2007

78. Holy Redeemer, view from Spa Fields Garden in 2007. Bay on left added in 1894–5

By 1892 Sedding was dead. The outstanding building debt had been paid off and Henry Wilson, his former assistant, was engaged to complete the church (Ill. 78). The work was carried out by T. Rider & Son of Southwark in 1894–5. (fn. 128) The new fourth bay was given over to a Lady Chapel, entered by way of two new vestibules opening off the transepts. Externally, Wilson's work is identical to Sedding's, though with the affectation of putlog holes.

In 1922 the north transept and vestibule were converted by Wilson into a war memorial chapel, dedicated to All Souls, with a mortuary chamber built out of the body of the church and screened by doors under the transept window. John Garlick & Co. were the contractors. (fn. 129) The wainscotting and mortuary doors are of Italian walnut, and the east end of the chapel is paved in white marble inlaid with green cipollino marble. In 1927 the mortuary chamber was decorated by Arthur Black with two murals based on Fra Angelico's work at the convent of San Marco, Florence. (fn. 130)

The oak-panelled sacristy, at the north-east corner of the church, was built in 1925 to replace a makeshift temporary structure. Wilson seems to have had no hand in it, the plans being drawn up by a builder connected with the church, F. T. Foulger. The contractors were Sims & Russell. (fn. 131)

Fixtures and furnishings (fn. 132)

Baldacchino (Ill. 77). Designed by Sedding, this is a close copy of the baldacchino in Santo Spirito, Florence, by the baroque sculptor Giovanni Caccini. Sedding seldom copied, and this may be why the Building News felt the baldacchino lacked 'that intense originality and "go" which usually characterised his work'. (fn. 133) Presumably Sedding was aware that the original in Santo Spirito was of later date than Brunelleschi's church (which is not otherwise a model for Holy Redeemer), and aimed at a similar contrast between a plain architectural context and the richness of the baldacchino. In its original form it consisted of the front half only, which was set against the temporary east wall, and extended to make a free-standing structure when the wall was taken down and the Lady Chapel created in the 1890s. The original capitals, and possibly the later ones, are by Frederick Pomeroy. Two gilded angel figures were mounted over the columns in 1892, and similar statues added after the baldacchino was enlarged; their authorship is not known. The enlargement involved the reconstruction of the dome itself on smoother, more inflated lines than the original. Sedding's dome, decorated with a gold cross, was shallower, with a slight depression at the top, and finished to imitate green copper fish-scale plates. Surmounting the baldacchino today, an ill-considered substitution for the cross, is a copy of the statue of the Risen Christ made by Henry Wilson for Tonbridge School in 1927. This was originally installed as part of a memorial to the first vicar, Edward Vincent Eyre (d. 1925), on the pedestal of one of the nave columns, with an ornamental cross as a backdrop.

High altar. The original modest altar was lengthened and re-cased in 1939 in green, yellow and white marble. It is decorated in relief with the symbols of the four Evangelists. The marble altar steps were installed the previous year.

Cancellum. Of pale grey marble with scagliola panels, this is of Italian manufacture and was installed in 1890 at the expense of F. A. D. Noel. It was extended along the north and south sides of the sanctuary in 1938, when the sanctuary was paved with black and white marble.

Pulpit. This is the original wooden pulpit of 1888, very plain, a panelled octagonal drum on columnar base, with a sounding-board hung from the nave column. It was presumably intended to be embellished or replaced.

Font. 1908–9, by Henry Wilson. At west end. Octagonal, monumental, of Portland stone (Ill. 74).

Piscina. Small seventeenth-century marble font from the Church of St Giles, Cripplegate, now used as a piscina in the Lady Chapel.

Stations of the Cross. Painted and gilded plaster in low relief. 1930–1, by J. E. Crawford.

Confessional. 1937, of panelled timber, in the south aisle.

Organ. On gallery at west end. From the Chapel Royal, Windsor. Rebuilt by Henry Willis & Son, 1888 and installed 1889; renovated and enlarged by Gray & Davison, 1927.

Altar and reredos, All Souls Chapel. White alabaster altar, with walnut reredos framing a semicircular bas relief Pietà in bronzed plaster, a copy of Wilson's bronze for the chapel of Welbeck Abbey.

Altar, Lady Chapel. Panelled in walnut. By G. E. Sedding (J. D. Sedding's son), 1913. The original altar was reinstalled at St Barnabas, King Square, Finsbury.

Reredos, Lady Chapel. Designed by Wilson, 1909, made by Traske & Co. Aedicular, of carved oak, incorporating a copy of Perugino's Virgin and Child in the National Gallery.

Magdalene Chapel (end of south aisle). The altar table, reredos and canopy are from a side chapel at St Philip's, Granville Square.

Sacred Heart Altar (north side in front of pulpit). 1955. Elaborately carved and gilded altar with scrolled retable, including antique panels.

Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham (south side of nave). 1962, with pedimented aedicule in walnut.

Crucifix. Free-standing, of c. 1922. Originally in mortuary chamber beyond north transept (now at West end near font).

Clergy house and parish hall

In 1898, the debt incurred in completing the church having been cleared, thoughts turned towards building a clergy house and a parish institute. By 1900 Eyre was preparing the congregation for the expense of a campanile soaring over the proposed house. (fn. 134) Consideration was also given to a porch or arcade in front of the church, to unite all three buildings with a common approach. (fn. 135) But it was not until 1905–6, soon after Eyre had retired, that the house could be built. Henry Wilson was the architect, and the contractors were Prestige & Co. of Pimlico. (fn. 136)

Built of London stocks with dressings of tile and red Fareham brick, (fn. 137) the clergy house occupies a narrow, tapering site. It is comparatively plain but for the upper stages of the bell-tower, where the use of flat and halfround tiling provides a richly ornamental texture. The tower's basilican-Lombardic style clashes with the Renaissance lines of Holy Redeemer. A connecting wing of the house uncomfortably overlaps the edge of the church façade (Ills 70, 76).

Inside the main feature of interest is the front staircase, of very plain Arts-and-Crafts character, constructed around a framework of four newel posts.

While the clergy house was in progress, a temporary iron parish hall was put up on the other side of the church. A fund-raising campaign for a permanent building was launched early in 1914, overseen by Lord Halifax. The iron building was sold for war use, and in December 1915 work on the permanent hall began, to be completed the following June. Wilson was again the architect, and the contractor John Garlick & Co. (fn. 138)

The parish hall, while harmonising with the church and clergy house in its materials, has little of their Italianate character. The plain brickwork in London stock is relieved by arches and banding in red tilework. In addition to the main hall the building originally included Sunday School classrooms and a billiard-room for the use of the clergy. (fn. 139)

Northampton Road Area

The area south and west of Spa Fields Gardens has lost all physical trace of its pre-twentieth-century character (Ills 47, 58). The trapezoidal block bounded by Northampton Road and Bowling Green Lane is largely occupied by buildings of the 1930s, principally the bulky Finsbury Business Centre. In Pine Street the revolutionary Finsbury Health Centre of the 1930s, and a slightly earlier maternity clinic, face the most reactionary of lowrise public housing from the late twentieth century.

The north—south arm of Northampton Road was the southern stretch of Rosoman Street until 1985. It was Bridewell Walk in 1755, when Thomas Rosoman took a 99-year lease of the whole plot south of the Red Lion tavern (site of the New Wells, see above). Some small houses had been built in the early 1750s to the north of his ground, and he followed these within a year or two with fourteen houses in what became Rosoman's Row. The name Rosoman Street was adopted in 1774. Rosoman himself had a house here throughout the 1760s. John Barnes, a watchmaker, occupied another that had 'sundry additions made on the Top of the same for a Workshop'. (fn. 140) Another clockmaker, Ainsworth Thwaites, was at the south end of the row, where his successor firm, Thwaites & Reed, stayed up to the 1880s. (fn. 141) Rosoman Street 'soon became the residences of retired tradesmen'; (fn. 142) among these was William Walker, an innovative engraver, who lived here in the years up to his death in 1793. Other residents in the years around 1780 included the engravers Richard Earlom (see above) and Robert Laurie; Ann Heydon, an enameller; Thomas Dobson and Robert House, watchmakers; James Omwer, a lapidary, and William Starling, a painter. (fn. 143) In his 1887 novel The Revolution in Tanner's Lane, William Hale White (Mark Rutherford) placed Zachariah Coleman, his fictional young printer and radical, in a house on Rosoman Street in 1814. At the south end of the street the Mason's Arms, later the John of Jerusalem, was rebuilt in 1854. (fn. 144)

Various cottages were built piecemeal on the land to the west of Rosoman's Row from the 1780s up to about 1810 (Ill. 56). A slaughterhouse was built on the north side of Bowling Green Lane in the 1780s, and back-to-back dwellings were built in the 1790s by James Aris (Aris Buildings and Lock's Buildings, later Gardens). Rosoman Mews and Fletcher Row were also formed in this period. The Northampton Estate and its surveyor, S. P. Cockerell, were then implementing planned 'improvement' of the Woods Close field, east of St John Street, but had no control over what was happening here under Rosoman's leases. (fn. 145)

79. Nos 47–57 Northampton Road in 1956. Demolished

By 1834, when the lease of a strip between the Rosoman lands fell in, the Estate had decided to cut through the chaos, by widening the path known as Garden Walk to form the main east—west arm of Northampton Road, with a southwards cut to Bowling Green Lane. An agreement for building along the new road was made with John Wilson, the developer of Spa Fields, now resident in Wilmington Square. To make way for the road the Red Lion was moved somewhat to the north in 1834–6 to become No. 23 Rosoman Street. (fn. 146)

80. Nos 35–65 Northampton Road, backs seen from Finsbury Health Centre, c. 1938, also showing Spa Fields Play Ground and former Clerkenwell mortuary. Demolished

Northampton Road was not properly formed until 1848–53, when Wilson and George Capron were the main builders of three-storey terraces, working under James Noble, the estate surveyor (Ills 79, 80). The fronts of these houses were unusual. Nos 37–45 were one window wide with pediments and possibly keystones over the first-floor windows. The adjoining row at Nos 47–57 had austerely brick-fronted upper storeys, in which broad sashes with margin lights were set back in recessed planes framed by pilasters and topped with rows of diglyphs. The simplified Classical detail recalls the houses overseen by Noble twenty years earlier in and around Sekforde Street in southern Clerkenwell (see Survey of London, volume xlvi).

Following the expiry of the Rosoman leases in 1854–5, more redevelopment was undertaken by Herbert Williams and Thomas Greenwood, surveyors. Douglas Place was built in 1854–8, by Thompson and Crosswell, of Islington. The back-to-backs were replaced, and Aris's Row became Howard's Place, the east side of which was developed in 1855. The south side of Fletcher Row was built up in the late 1850s, with William Partridge and William Crutch as builders. These houses were generally about 15 ft by 24 ft on plan, of two storeys, with small yards containing a washhouse and a privy. (fn. 147)