Pages 1-21

Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

Introduction

By the late eighteenth century the built-up area of Clerkenwell covered barely half the parish. Its growth since the Dissolution had been slow and accretive, nucleated on the former precincts of monastery and nunnery, and spread along the old highways and Fleet river. Densely built and densely inhabited, it had become increasingly industrial. The northern half of the parish, the subject of the present volume—in modern terms roughly the area north of Rosebery Avenue—remained essentially open country. Its character was mixed. On one hand were rubbish dumps, brickworks and livestock-pens. On the other was an Elysium of grassy meadows above the city, dotted with bowling greens, spas and other places of refreshment.

In contrast to slow growth to the south, the building-over of this northern tract was accomplished in just two or three generations. At the northernmost part the suburb of Pentonville, effectively an outgrowth of Islington, was a creation of the last third of the eighteenth century. But for much of the area development was then impossible, and might have remained so indefinitely but for the introduction of cast-iron water mains.

It was their installation around the New River Company's reservoirs in 1810–19 that freed for building what had become a 100-acre bubble in the capital's otherwise all-encompassing outward growth. For two hundred years, proliferating lines of wooden pipes had run across these fields to take New River water to London. Competition from other water companies finally forced the switch to more efficient iron piping. A single durable iron main, buried under a street, might take the place of many less reliable elm pipes on or near the surface. As luck would have it, this technological advance coincided with the end of a long war. The widespread building boom that grew through the decade up to 1825, feeding as it did the renewed appetite of the London economy for houses and yet more houses, made bricks and mortar irresistible to the handful of major corporate and private landowners in northern Clerkenwell. It is with the development and redevelopment of these estates that much of the present volume is concerned.

For topographical coherence, some districts first developed in the early nineteenth-century are described in volume xlvi (Ill. 1). These include the Woods Close estate of the earls and marquesses of Northampton, centred on Northampton Square; the frontages to the upper reaches of St John Street; and the Brewers' Company estate east of St John Street. Conversely, the present volume takes in the much older-developed area west of Farringdon Road, formerly called Coldbath Fields.

Most of northern Clerkenwell is residential, and this introduction confines itself largely to housing and planning—that of Georgian estate development and subsequent redevelopment, notably public housing of the twentieth century. To set the scene, it also deals briefly with the pre-development character of the area. The background to redevelopment in the twentieth century is discussed in relation to the area's changing status and, finally, recent changes are outlined. For a general introduction to the whole parish of Clerkenwell, and to its industrial, commercial, public and institutional buildings the reader is referred to volume xlvi.

The area before c. 1820

Medieval ownership of the fields of northern Clerkenwell was split between the two twelfth-century monastic foundations to the south. St Mary's nunnery had a swathe across the middle of the parish, later to be divided as the Baynes—Warner, Skinners' Company and Northampton estates, including Woods Close to the east (Ill. 3). The hilltop fields further north pertained to St John's priory. These became known as the Commandery Mantells, and were later to be divided between the Lloyd Baker, New River Company, Brewers' Company, Penton and Angel Inn estates.

The land was probably in arable use during the medieval period, and then essentially pasture by the sixteenth century. Several windmills, raised on circular mounds, were built by, or in the course of, the fourteenth century. A sixteenth-century depiction shows that one, where St John Street now meets Myddelton Street, was a wooden post mill; it had gone by 1624. Another, across the road about where the Northampton Institute was later built, appears to have been a brick structure. There were windmills on the west side of Coppice Row (Farringdon Road), while just outside the parish, on the east side of Goswell Road, the raised ground level of another and the name Mount Mill survive. (fn. 1)

The high ground of north Clerkenwell abounded in springs. Medieval London supplied itself with water from the vicinity, and the Charterhouse had its own supply piped from a spring at the White Conduit, just beyond the parish boundary near what is now the junction of Penton Street and Barnsbury Road. Water supply took on a new importance in 1613, with the opening of the reservoir and Water House at New River Head, for the storage and distribution of water channelled to London from Hertfordshire. This privately run waterworks was vital to the metropolis, but proved a cuckoo in the nest for local landowners.

As the New River Company prospered, New River Head was enlarged and the Water House embellished. The sumptuous Oak Room of 1693 survives within the former Metropolitan Water Board Offices which replaced the old building in 1914–20. An overflow or outer pond spread over more than an acre beside the original circular reservoir, and from the early eighteenth century water was pumped (initially by windmill) to a higher-level pond to provide a better head for supplying the West End. An ever-denser network of pipes crossed the fields to south, west and east of New River Head and, following the introduction of a steam-powered pump in 1766, subsidiary ponds were dug along some of the routes.

There was one important exception in this early picture of a sparsely populated area, largely given over to pasture and water-supply. This was at the north-eastern edge, where one side of Islington High Street fell within Clerkenwell parish. Islington was the first independent village north of London, and the high street was a busy halting point on a medieval main route linking Hertfordshire and the north with the livestock market at Smithfield and the City. Here, at the junction of four north-south roads, a strip of houses and inns had grown up by the fifteenth century. The street continued to flourish and by 1714 the west side boasted three big inns, the Angel, Peacock and White Lion, with an all-but-continuous thirty-bay frontage. Close by, sheep pens and cow layers continued into the nineteenth century, and the surrounding fields were let for grazing.

A more ephemeral presence was a significant section of the Civil War 'lines of communication', the ring of fortifications hastily flung up round London, Westminster and Southwark in 1642–3 as a defence against Royalist attack. From Mount Mill Fort, a large enclosure on the east side of Goswell Road, the main rampart line ran northwest up to the former mill mound on the west side of St John Street, which was named Waterfield Fort. The rampart continued along what are now the routes of Myddelton Street and Exmouth Market to the Coppice Row mound, where another battery and breastwork on the site of the Mount Pleasant Sorting Office was known as Pindar of Wakefield Fort. A spur rampart also ran north along the line of Amwell Street to the Fort Royal, a substantial structure with four demi-bastions, approximately where the west side of Claremont Square stands. (fn. 2) This was 'most rare and admirable' and 'marvellous perspicuous and prospective, both for city and countrey, commanding all the other inferiour fortifications near and about'. (fn. 3) In 1647, once victory was secure, this fort was demolished, and all other traces of these works have since gone.

Reservoirs and livestock apart, northern Clerkenwell was, above all, a playground in the two centuries before it succumbed to house-building (Ill. 2). Sadler's Wells is the great survivor of a raft of spas and other pleasure grounds. Southern Clerkenwell too had its recreations, with traditions of bear- and bull-baiting, cock-fighting and wrestling antedating 1600, and northern Clerkenwell had a share of such boisterous sport, including ponds for duck-hunting with dogs. But water tended to attract gentler pursuits, such as angling. Bowling greens, a typical suburban feature, were also present by the late sixteenth century.

It was the prevalence of springs that lay behind a cluster of health-promoting enterprises in the late seventeenth century: Sadler's Wells, where chalybeate water was found in the early 1680s beside a music-house of a decade earlier; New Tunbridge Wells or Islington Spa, where another spring was unearthed around 1684; London Spaw, where a medieval well was re-opened in 1685; and the Cold Bath, established in 1697, another ancient well rediscovered. The Cold Bath had (and retained) austere medicinal purpose, but the other resorts were essentially for pleasure, offering coffee, dancing and gambling besides the waters, some of which soon dried up. They had modest entrance charges and were unselective as to clientele. Already in the 1690s they were known for dissoluteness. Bad repute endured, but fashions were followed, and these out-of-town resorts permitted rare and remarkable laxity in social distinctions. New Tunbridge Wells enjoyed a subversive heyday of royal patronage in 1733, and Thomas Rosoman cut his managerial teeth at the disorderly New Wells 'Interlude House' of 1735, before going on to remodel Sadler's Wells in emulation of Vauxhall. A number of other resorts grew up from existing taverns, including Sir John Oldcastle's, the Cobham's Head, Merlin's Cave and (just into Islington parish) the White Conduit House, with a range of entertainments including music and fireworks.

The 1760s saw a whirl of improvements, with some substantial building projects and something of a shift towards indoor activities, bringing politeness and depravity into overt, and therefore uncomfortable, embrace. Bagnigge Wells tea-gardens, just outside the parish in St Pancras, had opened in 1759. There and at the English Grotto, where a newly dug pond generated an 'enchanted fountain', water was again an essential part of the attraction. Rosoman rebuilt Sadler's Wells in 1764, and among other new enterprises was the Belvidere, with its bun-house and teagarden, on the north side of the New (Pentonville) Road. Most ambitiously, and at the cusp of northern Clerkenwell's fortunes as a place of entertainment, the Spa Fields Pantheon was built in 1769. This domed and galleried neo-Classical rotunda, built in imitation of Ranelagh, at first drew thousands for tea and 'company', but closed within a decade. Things had got out of hand. Magistrates, the press and unfavourable comparison with the contemporary Oxford Street Pantheon—'Pantheons: The Nobility's, Oxford Road; the Mobility's, Spawfields'—put a lid on the Pandora's box of class miscegenation. (fn. 4)

2. Pleasure gardens, spas, inns and taverns in and around northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville before 1800

As Pentonville began to encroach, from the late eighteenth century, the resorts faded. New Tunbridge Wells carried on, diminished, up to 1840. Sadler's Wells, having had great popular success with the original clown, Joseph Grimaldi, and spectacular aquatic shows, went into decline in the 1820s. Outdoor recreation went on until the building-over of the fields. Near Bagnigge Wells an 'archery target ground' used by the Light Horse Volunteers existed for some years in the early nineteenth century. A grace note to this early history, harking back to the healthful origins of the spas, was the open-air gymnasium of the London Gymnastic Society, established in 1826 near the site of Percy Circus, for young working men to boost their physical and moral well-being. It was short-lived.

Alongside the fun and games, eighteenth-century outer Clerkenwell was also, like many other districts just beyond London, a place for less attractive establishments: 'Mount Pleasant', an ironically named dump, the parish workhouse, a smallpox hospital, a distillery and a prison (the Middlesex House of Correction) were concentrated in the area around the present junction of Farringdon Road and Rosebery Avenue. Brickmaking long antedated housebuilding locally, and from 1769 there was a large tile works near the site of Granville Square (London houses were roofed with tiles well into the nineteenth century). Even so, Spa Fields, as the western part of the Northampton lands around what is now Wilmington Square had come to be known, was still an open enough space in late 1816 and early 1817 to host mass assemblies of popular radicalism. By 1818 the ground was in the hands of brickmakers, and another intended gathering could not take place.

Estate development

Clerkenwell was at first slow to grow northwards from its nucleus around the parish church. The pipes and reservoirs of the New River Company, spread over the intermediate fields, were a major impediment. Legal restrictions on suburban growth may also have had some effect before the 1680s when Compton Street was laid out on the southern margins of the Northampton Estate's Woods Close property; a few scattered cottages around Merlin's Cave thereafter were probably encroachment. Any more coherent speculation may simply have been uneconomic before 1719 when building, deferred since 1692, began in earnest on the Baynes—Warner estate. There several streets were laid out around the Cold Bath, and building continued into the 1740s. Some of the houses survive in Mount Pleasant. Even more modest initiatives followed to the east on Northampton land in the 1750s and 60s, in the shape of Rosoman's Row and Brayne's Row. Something of the latter, which originally had front gardens and views across Spa Fields, survives on the south side of Exmouth Market.

All this was small-scale compared to the development of Pentonville on the estate of Henry Penton, which stretched from Islington High Street to Maiden Lane (present-day York Way). The key to its development was the coming of the New Road in 1756, to which Penton's land had a large frontage. Running from Paddington to the Angel, well north of previous urban limits, the New Road was formed not to improve access to the districts along the way, but as a bypass to keep traffic, especially livestock, out of the West End by funnelling it through Clerkenwell. In due course this influential project opened the way for a northward leap in development. But that was not how it was seen at first.

Pentonville to start with was not really part of the metropolis. With its elevated position giving views over the city, and fresh, breezy air, this was, indeed, much of its appeal. After a slow start, it grew steadily, at first as an anonymous adjunct of Islington, acquiring its name only in the 1780s.

The first building agreement came in 1764 with the general post-war upturn in building, but despite the auspicious times it was 1769 before work actually began, the first houses being in a terrace set well back from the highway, as the New Road Act required. Subsequent early development was concentrated near the resorts on Penton Street, leading north from the Belvidere tavern to White Conduit Fields and the open country beyond. Building reached a peak in the 1780s, petering out thereafter as war again claimed finance's priority. There were plain terraces, somewhat irregular and without great aspiration, but among them a number of good-sized houses had big bow windows for the enjoyment of views, and there were some substantial villas, such as Hermes Hill House, which had a landscaped garden. The westernmost part of the Penton estate, sold off in 1806–7, was not built up until much later and, with industry hard by, its character was poorer.

That Pentonville was strung along a major new road perhaps obviated any requirement for a square, and the grid of streets that began to emerge in the 1770s was centred on the pre-existing line of Penton Street. It grew up in phases, and responsibility for the layout remains unclear. Though the surveyor James Carr was involved around 1780, it is not evident that he had any significant enduring role. Aaron Henry Hurst's architectural input into the area only came later, and seems not to have gone far beyond designing Pentonville Chapel. Pentonville's simple block-by-block regularity is a point of interest because the 1760s had been an obsessively rationalizing decade as regards improvements to London, yet grid layouts remained unusual in its environs away from the West End. But too much should not be read into it. The shape of the estate lent itself to this sort of street-pattern, and any superficial resemblance to contemporary urban planning, such as the layout of Edinburgh's New Town, begun in 1767, is perhaps merely coincidental.

By the 1790s Pentonville was a fully-fledged suburb with prosperous inhabitants, its identity reinforced by possession of a chapel-of-ease. It extended westward to present-day Killick Street, and it reached south of the New Road down what are now King's Cross Road, Penton Rise and Weston Rise. After 1815, as new streets filled the intervening ground south to old Clerkenwell, the name of Pentonville was naturally assumed by the inhabitants of the new neighbourhoods. Pentonville, once more or less synonymous with the Penton estate, came to designate most of northern Clerkenwell. Such was the dominance of the name that, by the 1840s, King's Cross Road was sometimes called Lower Road, Pentonville, and Islington High Street was referred to as Pentonville High Street.

3. Principal landholdings and owners in Clerkenwell, c.1800

The first signs that Clerkenwell and Islington would eventually join up, and the latter be fully annexed to London, came naturally around the course of the two main roads, St John Street and Goswell Road. Two developments on the Brewers' Company land, Gwynne's Buildings on Goswell Road (1765) and Rawstorne Street, begun in 1789, hard up against the north side of Woods Close, provided an abutment for the first bridging of the gap. In 1791 Edward Boodle and Samuel Pepys Cockerell launched a project for covering Woods Close with streets and houses, so as to address Lord Northampton's financial difficulties. A dispute ensued with the New River Company, whose lease of land there around its south-easterly main from New River Head was soon to expire. The company was able, in effect, to hold the Estate at bay by invoking the dire consequences of impeding the City's water supply. It was 1805 before building began at Northampton Square, the centrepiece of a revised plan aligned to the existing water mains. This project was essentially complete by 1815, but most of northern Clerkenwell remained open: a prime development opportunity on the edge of built-up London, enclosed by houses to south, north and east.

The New River Company itself owned about half of this open land. From 1805 it faced stiff competition from other water companies, and modernization became imperative. It was evident that the introduction of efficient castiron pipes, begun in 1810, would allow further gain through land development. The company's surveyor, William Chadwell Mylne, quickly prepared first plans for streets, but little was done before an upswing in the building market. From 1819 progress was frenetic, with around 400 houses covered in by 1829, the best of them around Myddelton Square, in which a church had been built.

Neighbouring landowners were not idle through the boom years that followed the post-war housing shortage. The Northampton Estate found a developer, John Wilson, to undertake the transformation of Spa Fields, seen through from 1817 with Wilmington Square at its centre. The Skinners' Company began an equivalent project on its field in 1818, through its surveyor William Jupp and another developer, James Whiskin. The Lloyd Baker family was slowest off the mark. After much dithering, the laying out of its hillside ground to the west of New River Head was taken in hand in 1819, under the ostensible control of the surveyor John Booth who, in an echo of the laying out of Northampton Square, was obliged to situate and shape Lloyd Square so as to permit free access to another water main. The decade to 1821 saw the number of houses in the parish rise by more than a thousand, a 29 per cent increase from 4,166 to 5,382, and the following decade witnessed an equivalent absolute increase to 6,537. By this time the population of Clerkenwell had more than doubled from 23,396 since 1801. (fn. 5)

Development was held up by the general collapse of the building market from 1825, and Clerkenwell's last substantial pieces of open ground to the north-west were not built up for many years. The last phase saw the building of Granville Square on the Lloyd Baker estate (1839–43), much of Northdown Street in west Pentonville (begun much earlier but then left until this same period), and Percy Circus and Holford Square on the New River estate (1838–53). In the meantime, areas which had been on the periphery of built-up Clerkenwell, notably the Seckford estate and Northampton land south of what is now Exmouth Market, were improved through redevelopment around new roads.

The planning of northern Clerkenwell between the 1760s and the 1850s bequeathed to the area a townscape that has been widely admired since the 1920s, extensive redevelopment notwithstanding. Even judged against West End standards there are terraces, squares and other set pieces with dignity, grace and even grandeur. However, as Ian Nairn said of Myddelton Square and Lloyd Square: 'They need to be seen as part of an unselfconscious chain, not as isolated architectural specimens'. (fn. 6)

Pentonville offered a specimen of plain, rational, orthogonal planning. But in suburban developments after 1815, a more enterprising geometrical layout was taken for granted. Squares were de rigueur, when there was room. When not, on the Skinners Company and Seckford estates, streets were made to intersect at acute angles. There were other significant differences of approach. For the Northampton estate S. P. Cockerell advocated a balance between better houses on central squares and lesser houses for tradespeople and labourers at the margins. This prescription was not followed elsewhere. Indeed, the Lloyd Baker Estate shut the door firmly on possible contamination, declining to provide links to the Northampton estate north of Wilmington Square, where standards were thought to be threateningly low.

It was the emergent specialism of estate surveyorship that was the key to success. No one proved abler here than W. C. Mylne, who, though first and foremost a water engineer, kept development on the New River estate carefully geometrical and closely controlled for fifty years. Boodle and Cockerell, who was a superior architect, fared less well as controllers, if only for want of assiduity. Yet difficulties with water pipes were elegantly resolved in the diagonal offset of Northampton Square. John Booth and his son William Joseph Booth achieved similar success with Lloyd Square, where a scheme for a crescent was rejected. Their slow but competent progress was closely watched by the Lloyd Baker family up to 1830. Perhaps most masterful was the resolution of Percy Circus, on a hillside site, by Richard Cromwell Carpenter with Mylne. There another pipe along the diagonal of Prideaux Place and Vernon Rise necessitated awkwardly irregular entry points, which probably inspired the resort to a circus in the first place.

There was an exceptional degree of liaison and co-ordination between the major estates in the years around 1820. This is most obviously manifest in the way that Mylne and the Booths managed the interfaces between the New River and Lloyd Baker estates, adopting each other's idioms for the sake of integrated and continuous elevations on Amwell Street, Great Percy Street and Cumberland Gardens. Similarly, Cockerell and Mylne appear to have collaborated in the radial layout whereby Tysoe Street and Garnault Place mirror each other on either side of a junction that was intended to have a semi-circus. Another semi-circus was projected by Cockerell for the west end of Spencer Street. Neither materialized.

After all the house-building the district was left with little open space. Pentonville gradually filled up, and there was no more than a modest churchyard around Pentonville Chapel. Elsewhere, one early nineteenth-century square (Claremont) was opportunistically built round a reservoir, and two others (Myddelton and Granville) had much ground taken by Commissioners' churches even before most of their houses had been built. John Wilson's failure to secure a road link across the House of Correction (Mount Pleasant) site combined with a depressed market in 1828 to persuade a new generation in control of the Northampton estate to permit a reduction in the size of Wilmington Square.

At the level below that of the surveyors the mechanics of development were variously handled. In just two places—the Northampton Estate's Spa Fields and the Skinners' Company estate, both begun around 1818—were the building projects sub-contracted to a single developer. Elsewhere the estate surveyors attempted to maintain control over numerous small undertakers, the usual late-Georgian mixture of men in the building trades and others for whom investment in building was effectively commodity speculation. Watch- and clockmaking was Clerkenwell's most important trade, and a number of entrepreneurs from that background duly became speculative developers. Alexander Cumming was perhaps the first major instance of this. Of Scottish origin, he had been in London for many years and maintained a high standing in his trade when, in 1779, he acquired a large parcel of Penton land. He took another, and his brother John a third, in 1786, and these were seen through to development on either side of a street bearing their name. The brothers Thomas and Richard Carpenter, the latter the father of the architect Richard Cromwell Carpenter, were of local origin. Sons of a watch-case maker, they kept up that trade and also tried their hands speculating with livestock, and as developers, Thomas at and around Northampton Square in 1804–10, Richard at Arlington Way in 1822–4.

Many investors moved in from neighbouring parishes. In the late 1780s Joshua Hodgkinson, a lime burner and bricklayer, took his building activities from St Pancras eastwards into Pentonville, and more than twenty years later a group of businessmen with links to the window-glass trade moved north from Holborn. It was a Holborn grocer, Henry Minter Fyffe, who took on redevelopment of the Angel Inn in 1819, and a relative, Edward Cowper Fyffe, was a major developer on the New River estate until he fell bankrupt in 1824. The usual eighteenth-century practice of work-for-work agreements, or cross-contracting consortia of tradesmen, endured here and there, even into the 1820s. There was some, but not great, continuity of building personnel as activity moved from one estate to another. In particular, a number of the more ambitious builders on the New River estate also worked on the Lloyd Baker estate. Bankruptcies were frequent and disruptive. After the financial crisis of 1847 the New River Company turned to one substantial figure, James Rhodes, to sort out its last vacant plots.

The New River and Lloyd Baker estates were the most tightly controlled, but even there irregularity and corruption crept in, from the innocence of builders who made their own houses a bit wider or taller than those of their neighbours, to the culpability of embezzlement, the most egregious example of both being John Scott, a brickmaker, who fled his big Claremont Square house in 1834 having taken some £10,000 from parish funds. A year before, James Blackburn, the developer of two sides of Lloyd Square, had been transported to Tasmania for forgery.

Leasing policy was, of course, a major aspect of estate management. Length of term mattered, as the Skinners' Company found in the 1820s. Its relatively short 70-year lease to Whiskin proved a hobble as it compared unfavourably to the longer terms (up to 99 years) being offered on neighbouring estates, and probably doomed its estate to irredeemable inferiority. The Penton Estate's failure to synchronize lease-expiry dates caused problems later. Strictness of control in the timing of the grant of leases was just as crucial. Relatively lax, the Penton and Northampton Estates signed leases before houses were completed, or even, in some cases, begun, and then failed to impose or enforce covenants against back-building or infill development. In contrast, the New River Company only granted leases once houses had been covered and certified by the district surveyor, and was tenacious in enforcing covenants.

It was back-building more than any other single factor that sowed the seeds for decline. Already before 1815, as across much of London, speculators desperate for a return in difficult times intensified development by squeezing courts of two-room houses for the poor into gaps between streets. These instant slums appeared south of what became Exmouth Market, and in much of Pentonville. A high proportion of the 846 houses built in Clerkenwell in the first decade of the nineteenth century were of this nature. Thereafter Mylne and others at the New River Company ensured that this kind of low-class house-building was prevented, to protect the value of their investment in development. Similar acumen on the Lloyd Baker estate may have been more rooted in old-world snobbery sitting in Gloucestershire, but it had a broadly similar effect, ensuring a predominance of middle-class occupancy, and relatively long-lasting respectability. The Northampton Estate did not learn this lesson, and mean infill around Northampton Square and Wilmington Square carried on up to about 1830.

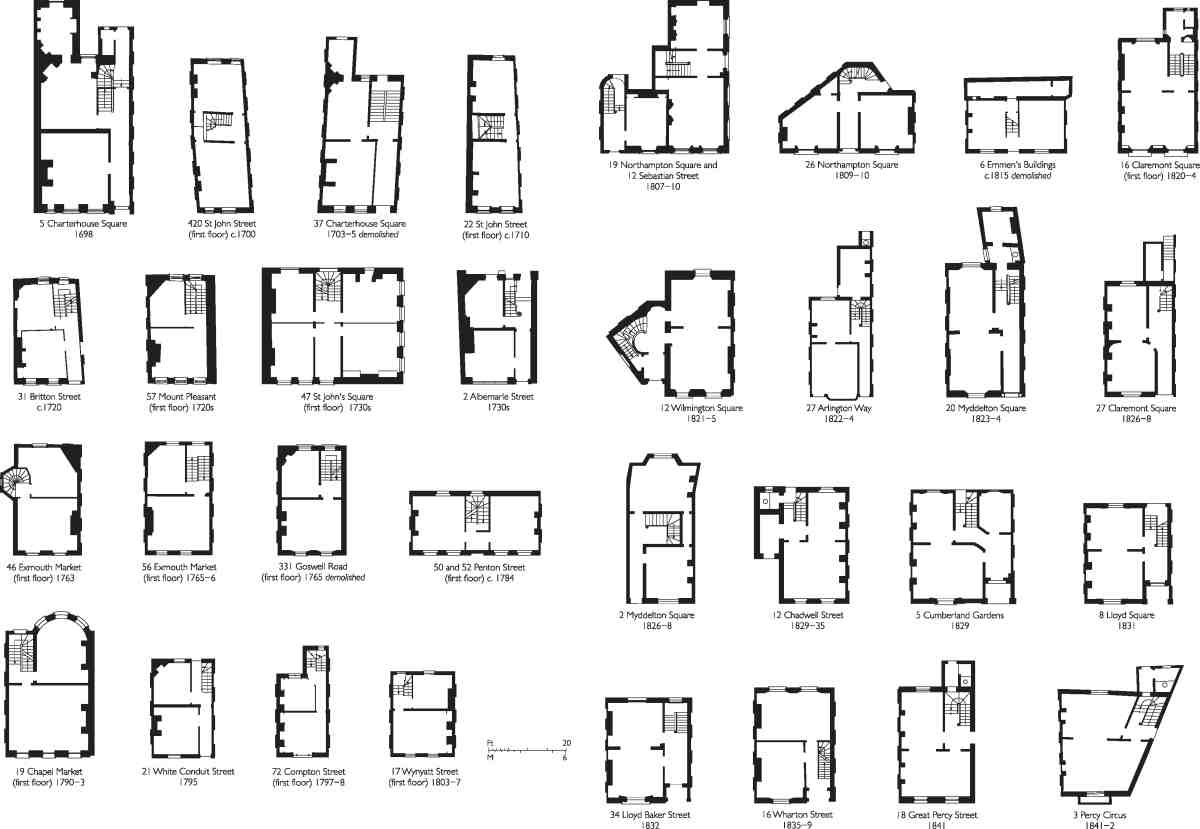

4. Clerkenwell house plans, showing range of archetypes and variants, 1690s to 1840s. Plans are of ground floor unless otherwise indicated

Leaving aside the smallest one-room-plan houses, often no more than 10ft square, which do not survive, and for which plans are seldom to be found, the laying out of individual houses in Georgian Clerkenwell is readily tracked (Ill. 4). Plans followed a typical pattern of development for London north of the Thames, though not without some interesting variation. At both ends of St John Street there are typically late seventeenth-century central-staircase plans, a form that persisted throughout the eighteenth century in shop-houses and where frontages were narrow. At Charterhouse Square and on early eighteenth-century streets, such as Britton Street and Mount Pleasant, the rear-staircase plan that was becoming the West End standard was introduced. There were few deviations from this basic type later on, though, unlike in the West End, angled rear stacks remained the norm up to about 1800, to cope with relatively narrow (16–17ft) plots. Opportunities to enlarge back rooms were taken in the later eighteenth century, when space permitted, as at No. 46 Exmouth Market and No. 19 Chapel Market, where a full-height rear bow briefly gave views across Islington's fields; and when very narrow plots forced improvisation to escape the cramping consequences of the rear-staircase layout, as at No. 72 Compton Street. Sometimes width was not a constraint. Double-fronted single-pile houses were built in Penton Street in the 1780s, and, much later (around 1830) and less expansively, where plot depth was lacking, on the Seckford estate and in Buxton Street on the Brewers' Company estate. Generous plot-width characterizes the Lloyd Baker estate's unusually proportioned houses. However, builders complained that these wide properties were hard to let, and managed to negotiate some reduction in scale. In the late 1830s Thomas Herridge deployed front staircases on the north side of Wharton Street, where there were long gardens with, for a short while, open land beyond, and at least one house on Lloyd Square (No. 21) has a central-staircase plan. Irregular plot shapes were also something of a Lloyd Baker specialty, right angles being scarce in the layout of its streets. Similarly, corner entrants at Northampton Square and Wilmington Square necessitated some improvisation, as did an odd junction of large and small houses where Northampton Square meets Sebastian Street. W. C. Mylne and the New River Company adhered to greater standard-plan regularity, even in the segments of Percy Circus, though they did use end-of-terrace side entrances and ensured that back projections were added, for water closets.

Attention has already been drawn to the success and value of northern Clerkenwell's estate architecture as townscape, but it remains to give some brief consideration to 'architectural specimens'. Viewing these in a broad sweep, there is a simple contrast between, on one hand, the plain surveyors' elevations by the anonymous and the ponderous (from Pentonville through to Mylne and embracing later Cockerell) and, on the other, the young-man's flair that found expression on the Lloyd Baker estate and in Percy Circus, with the work of W. J. Booth and R. C. Carpenter. Thus, taken in isolation, some streets, however handsomely proportioned, have or had the dispiritingly monotonous impact conveyed by Sir John Summerson's remark about Georgian Dublin, 'one damn house after another'. The early nineteenth-century streets of the Skinners' Company estate and Myddelton Street area all once had the standardized aspect that led Victorians to call the Building Act of 1774 the 'Black Act', though it was the increasingly efficient capitalization of building, not legislation, that was the main cause of this. The uneven rooflines and plot-widths of Chapel Market are a reminder that late eighteenth-century Pentonville retained something of the harmonious variation seen in earlier Georgian building, as on the Baynes—Warner estate.

Continuous first-floor blind arcading lifts many terraces away from monotony. Cockerell, when relatively young, had helped to introduce this treatment to north London, probably taking his cue from George Dance the Younger's east side of Finsbury Square of the 1780s, though it had already been tried by James Carr in the 1790s at Newcastle Place in southern Clerkenwell. It appeared at Northampton Square from 1805, and spread wildly, well beyond the confines of these volumes. Although absent from the earliest New River Company developments, it became standard after 1815 and continued in use even into the 1830s, there and on the Seckford estate.

Cockerell seems otherwise scarcely to have engaged with Clerkenwell's architectural appearance, and it is tempting to absolve him from responsibility for the weak 'palace fronts' of Wilmington Square. His son, Charles Robert Cockerell, a yet better architect, took on the Northampton surveyorship only in 1827, too late to have any impact there. He delegated responsibility for the redevelopment of the Seckford estate thereafter to James Noble, a competent understudy. Mylne, on the other hand, was omnipresent for five decades—committed and steadfast, but unimaginative. Yet, for all its regularity, its stock brick and stock ironwork, the New River estate has great appeal when examined closely. Much of this lies in idiosyncrasies of detail that would have irked Mylne.

The Lloyd Baker estate's widely appreciated 'pedimented style' was probably due to the youthful imagination of W. J. Booth, and devised around 1819 in a conscious effort to set the estate apart. Eminently suited to picturesque repetition in hillside terraces, on Lloyd Baker Street it used the by-then standard blind arcading in a novel form. The consistent use of this style on the estate throughout the 1820s is made the more charming by many minor adjustments made to cope with changing levels and irregular plots. Architectural inspiration appears to have deserted the Booths in the 1830s, their designs slacking off in the very plain Granville Square.

In the last phase of estate development architectural panache was supplied by R. C. Carpenter. For a few years from 1838, before he was able wholly to devote himself to Gothic Revival ecclesiastical architecture, he lent his shrewd eye to the Italianate style for the Percy Arms public house, a careful pastiche of Barry's Travellers' Club, before moving on to Percy Circus and the delightful resolution of that complex architectural problem. Robert McWilliam's terrace of c. 1840 that marks the completion of Pentonville on Northdown Street presents an isolated Greek Revival flourish.

Social character and perceptions

No sooner had it been completed than northern Clerkenwell, or Pentonville, as Victorians knew it, began to shift in character. It is the perceptions of those who leave written testimony that endure, and the rhetoric of decline has perhaps been heard too often. Money did move away, and poverty did increase, but the population has always been socially diverse. There were some solid middle-class beginnings, and the first inhabitants of the new houses included many professionals, and not a few writers. But even in the 1820s this was too far east to be properly fashionable; a decade later Dickens jibbed at the rents.

Perspectives and tastes differed. In 1853 a correspondent to The Builder wrote that Clerkenwell 'embraces in its

higher portions, on the heights of Pentonville, some of the most salubrious and pleasant squares and semi-suburban

retreats that are to be found in the metropolis'. (fn. 7) But to the barrister John Hodgkin, from a talented Quaker family

that lived in Penton Street from about 1798 to 1814, the area had lost its charms as he looked back from the 1860s:

take a glance at a district formed by striking a circle with the radius of a mile, and the New River Head as a centre, & you

will find one of the most uninteresting and least agreeable regions which can be found in the dull belt of faubourgs which

separates the active heart of the city from the first patches of green fields, cockney gardens, & suburban villas. Sixty years

ago my father used to delight in describing our residence … as situated on the top of the first hill north of London. This

expression now seems as if it could only have been used in burlesque, quite appropriate as it was then. (fn. 8)

Whether as barristers, doctors, merchants, artists, printers, publishers, booksellers or watchmakers, Pentonville's more prosperous residents worked, frequently from their homes. This may have been anticipated, as the area has little of the domestic stabling that commuters would have desired. Print artists were a notable part of the gradual northwards migration of Clerkenwell's specialist skills. From late eighteenth-century concentrations on Brayne's Row (now Exmouth Market), Rosoman's Row (Northampton Road) and the south side of Pentonville Road, artists and engravers spread on to new streets in the nineteenth century. Amwell Street was for many years home to George Cruikshank, as well as to others less renowned—some, like Cruikshank, with radical leanings. Another newly professionalized design trade was also well represented in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, when the area was home to a number of architects, many of them minor practitioners.

Clerkenwell's metal-based trades also expanded northwards as development took place, and domestic industry continued to be the norm. Watchmakers, silversmiths, jewellers, carvers, gilders, penmakers, brass founders, scientific and surgical instrument makers, barometer and chronometer makers, all could be found living and working in and behind the new houses. By the 1840s watchmaking was well established on Exmouth Market and Pentonville Road, as well as in Wilmington Square, Myddelton Square and Holford Square, and it was dominant around Northampton Square. Borchert Brunies, a German 'fancy whalebone worker', was the first resident of Percy Circus in 1842, and instrument makers included Antonio Pastorelli, a barometer maker on Wharton Street. Such occupancy spread through the later decades of the nineteenth century and was increasingly characterized by immigrants, notably French and Swiss, as at Myddelton Square. Artificial-flower making was widespread, and especially concentrated at Wilmington Square from the 1850s, largely in the hands of French and German immigrants. The same might be said of furriers at Northampton Square in the late nineteenth century.

As skilled manufacturing spread few streets remained purely residential. The highly specialized nature of many

small-scale activities must have given an esoteric, even occult, atmosphere to buildings that, before appreciation of

Regency and Victorian architecture revived in the later twentieth century, were commonplace or quaintly old-hat.

Arthur Machen, who returned again and again in his writing to the districts of St Pancras, Islington and especially

northern Clerkenwell, recalled his discovery in about 1894 of the district east of King's Cross Road:

I shall never forget the awe with which I first came upon the other Baker Street, the Baker Street which would never enter

any taxi-driver's mind; those houses climbing up the hill into Lloyd Square, stucco houses with classic pediments, but all tottering, askew, and falling into decay: the jerry building of 1820–30. And, I remember, seeing on one of the leaning and doubtful doors here the brass plate of someone who said that he was a 'Buhl Maker'. I wonder. Did someone really labour in that

forsaken, climbing street in that rich eighteenth-century art of brass and tortoiseshell, fashioning curious cabinets and

escritoires! How unlikely it seemed … (fn. 9)

There was art and craft, but there was also dearth and distress. Beside manufacturing and middle-class residents whose houses were not used for work, the area also had a strong working-class presence, from clerks to labourers. The Spa Fields Meetings of 1816–17 left an imprint, as displayed in the character of Zachariah Coleman, William Hale White's fictional Rosoman Street printer. (fn. 10) Alongside artisan radicalism was growing poverty. Mean courts were already widespread by 1830, and such poor accommodation continued to be built up to the 1860s: on the Penton estate in the Weston Rise area and to the north-west, as at the misleadingly named North Avenue of 1845. Spa Cottages, a similar enclosed court, filled up the last of the New Tunbridge Wells site in 1840, and Rydon Crescent of 1859–62, just to the north, was only marginally better.

A measure of the disregard that goes with lowly status was the overfilling of Spa Fields burial ground, where horrific practices were exposed in the 1840s. A decade later Henry Mayhew found the Cold Bath area to be 'dingy and distressed', and conditions across Clerkenwell prompted concerns about sanitation in 1864. (fn. 11) The area was acquiring new and poorer residents, many of them displaced by clearances and road improvements elsewhere. These pressures tended to move from south to north, but even the New River and Penton estates had always had mixed populations. In Pentonville Road, the London Female Penitentiary, an evangelical reformatory for prostitutes, was established in 1807; the similar Home for Penitent Females in White Lion Street opened in 1844. The closure of these institutions in 1883–4 came at a time when the Penton estate was increasingly populated by unskilled labourers such as porters and carmen, and concerns about poor housing in more southerly districts were coming to a head. Immigrants, notably Russians, Poles, Germans and Italians, were generally poor. The Italians were concentrated in the streets to the south of Mount Pleasant, in the spread of Little Italy north from Holborn. Initially this substantial community included numerous craftsmen, but it was later more typically characterized by street vendors.

Between 1841 and 1881 Clerkenwell's population grew by about 20 per cent, but the total number of houses in

the parish remained broadly static. Higher-density lodging-houses, slums and model dwellings proliferated. (fn. 12) Some

houses had been lodging-houses from the first, often run by women, and typical of much of the rest of London;

in the 1870s it was claimed that as many as three-quarters of London houses were divided as lodging-houses. (fn. 13)

Lodgers included students, immigrants and young professionals, men such as Herbert Spencer at Holford Square

in 1847, Walter Sickert at Claremont Square in 1880–1, and V. I. Lenin at Holford Square in 1902–3, as well as the

downwardly mobile, like the fictional Rev. William Merrydew who, in moving to Percy Circus, believed that:

he and his daughter would be making "a change for the better," instead of taking a big step down the social ladder, as some

might fancy. He expatiated on the comparative salubrity of the situation at Pentonville. It was not so fashionable as

Kensington, but it was almost as fresh, for it occupied the only high ground between Kensington and the city; and it was

much more convenient than Kensington for the theatres, the shops, the streets, and all the daylight and gaslight distractions

and dissipations of town. Then that view from the top of Great Percy Street which they had before they went into the house!

It was almost as extensive as that from Highgate Hill. (fn. 14)

The boarding-house was a less respectable denomination in the sliding scale of multiple occupation. Granville Square became packed with them, and by 1860 there was at least one in Wilmington Square. In the courts behind that square and in many other places even the meanest houses came to be divided, generating classic slum conditions, with a family to a room, some rooms being as small as 9 ft by 8 ft. Crime and vice were endemic, and George Gissing's The Nether World of 1889 was largely set locally. The story places Bob Hewett, a coin counterfeiter, in a slum cottage on Merlin's Place, and describes the dark purlieu of Myddelton Passage, where, in reality, bored policemen gouged their collar numbers into a brick wall.

Model or industrial dwellings were an important aspect of rising densities, sometimes conceived as improvements, sometimes simply as private infill speculations. Of the former type was Cobden Buildings on King's Cross Road, one of the earliest developments by Sydney Waterlow's Improved Industrial Dwellings Co., which moved on to work with the Northampton Estate in the 1870s. Private tenements included model dwellings on Hermes Street, built for Thomas Flight, a slum landlord on a large scale, to designs by Banister Fletcher, the architect and promoter of the Sanitary Dwellings Co., which built more blocks near by.

House farming, by which unscrupulous landlords split properties, often on the ends of leases, for renting to the greatest possible number of tenants, exacerbated overcrowding. This was a much wider problem, but when the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes was formed in 1884, with the local MP William T. M. Torrens as a member, the notoriety of such abuses on the Northampton estate led to its selection as one of the leading case studies. Clerkenwell Vestry was exposed as dominated by house farmers and the Estate escaped primary blame, though its slack management had contributed to decline. Lord Northampton's son, Lord William Compton, told the Royal Commission that many regarded model dwellings as 'a sort of prison; they look upon themselves as being watched'. (fn. 15) On the estate the clearance and redevelopment approach was discredited, and direct management of the kind favoured by Octavia Hill was preferred as a way towards gradual improvement. Elsewhere blocks continued to be an attractive option for those who could afford the relatively high rents, but were not well-off enough to move to better housing in the suburbs. More were built in the years around 1890, notably by the Artizans', Labourers' and General Dwellings Co., at Coldbath Buildings, Gray's Inn Buildings and Northampton Buildings.

The first two of these blocks were a consequence of the formation of Rosebery Avenue, begun in 1886 and completed in 1892. The last of Clerkenwell's major road improvements, this municipal initiative brought further slum clearance around the western parts of its route. More and better model dwellings arose at the hands of James Hartnoll, whose Rosebery Square Buildings were of a higher specification, each flat having its own WC and scullery. Hartnoll was also responsible for Barnstaple, Bideford and Braunton Mansions, middle-class residential blocks (sometimes called French flats) of a yet higher standard, and, in principle, profitability. These gave the lie to equivalence between block-living and low status, but their sites had been intended for people displaced by the road improvement, who were obliged to move elsewhere. This almost certainly contributed to the deterioration of the area to the north.

There, on the Penton estate, mixed habitation had long since included cottage courts and model dwellings, as well as dense multiple occupation in houses; in 1885 No. 13 Chapel Street housed 36 people sharing one WC. Yet, until about this time, substantial houses on Cumming Street and Rodney Street maintained carefully laid-out gardens. Leases were falling in, though not together so as to enable coherent redevelopment. By 1891, when the parish as a whole had significantly fewer (14 per cent) houses than it had had a decade previously, White Lion Street was accommodating about ten people per house, as opposed to about seven fifty years earlier. (fn. 16)

Circumstances combined to bring sharp change for the worse around 1900. As the assistant priest at St Philip's,

Granville Square, said in 1898, 'the whole parish is reported to be going down'. (fn. 17) The collapse of watchmaking in

the face of foreign competition was a factor:

Many of the houses are now used for other purposes, while in the case of those still devoted to the old crafts the master-men

no longer, as a rule, live over their shops, and the artisans find their homes elsewhere. Their place has been taken by a lower

class, policemen, postmen and warehousemen at the top, casual labourers at the bottom. It may be said that those who work in

Clerkenwell do not sleep there, and those who sleep do not work there. The district is no less respectable, but is certainly poorer. (fn. 18)

This alludes to another change. Improved public transport was enabling all but the poorest to move away and to commute back for work. For the first time, the census of 1891 found that the population of the parish had declined, a trend that was to continue. The lure of new suburbs drew tradesmen from rooms above the shop to a villa near the bus stop. The introduction of electric trams in 1900 made the suburbs even more convenient. Asking the Penton Estate for a rent reduction and help with repairs, a lessee of houses in Donegal Street and Penton Place wrote in 1910 that 'I shall be thankful to you, as the neighbourhood is deteriorating, owing to the Electric Traction, making it easier, and cheaper, for people to get further away'. (fn. 19)

Despite their negative image, model dwellings continued to draw other working people away from subdivided, dilapidated old houses. Lodging-houses became uneconomic and old buildings, often shoddily built by later standards, were wearing out, placing a burden on lessees faced with demands for repairs. Where new long leases were granted, in return for substantial repairs and modernization, lessees had to pay high premiums and substantial ground rents on top of the costs of these improvements. Demographic change left them financially exposed. One class that suffered particularly was the leasehold landlord with a number of houses let on yearly tenancies, for it was the relatively affluent yearly tenant who was particularly likely to move away. As old tenants left, houses or large apartments could often only be let in rooms on weekly tenancies—an altogether riskier and less lucrative arrangement. In this unstable market, bad tenants tended to drive out good, and the effect was exacerbated by generally poor economic conditions. Rowdy neighbours discouraged investment in rebuilding or improving old houses, producing a spiral of decline.

In 1904, upon the municipalization of water supply, the New River Company was reformed to continue as a property company. Thereafter, as leases fell in, it kept its houses under direct management, undertaking repairs and some outright conversions into flats. The company also built anew on Cruikshank Street in 1909–10, putting up maisonette flats with a hint of neo-Tudor style, in an attempt to hold on to some of the area's aspiring residents in what it called 'the best residential quarter left in Finsbury'—note the new appellation. This was a unique initiative locally, so the buildings, of a type common to London's Edwardian working-class suburbs, look oddly out of place. The Northampton Estate intended similar redevelopment on Margaret (Margery) Street before war intervened. Instead, it carried out the area's first lateral flat conversions, at Wilmington Square in 1920, an example followed by the New River Estate, which also redeveloped some sites with blocks of flats in the 1930s, at Prideaux Place and Claremont Close, again in a suburban manner. The Lloyd Baker Estate built a block of flats for middle-class tenants, the neo-Georgian Archery Fields House, in 1938–40. By this time public housing, discussed hereafter, had become a presence.

The name Pentonville had retreated to its original bounds. In its eastern, predominantly commercial part the Penton Estate was able to bring about extensive rebuilding, much of it on a more or less like-for-like basis, up to the 1930s. Much of this, in Chapel Market and White Lion Street particularly, has survived.

Further south things were more static. In 1906 Geraldine Mitton remarked on how the 'small squares' north of

Lloyd Baker Street had the 'air of being in a back-water … deserted and very quiet'. This she attributed to the

steepness of the ground being a discouragement to traffic. (fn. 20) Arthur Machen was more lyrical and more enthusiastic, describing an approach from King's Cross Road:

Then a steep hill rises before you, and a green grove. The hill is Great Percy Street, the grove stands in the midst of Percy

Circus. The architecture here seems to be of the 1810–50 period; and now, I would say, we are come into the Silent Land.

Here should the studious man dwell, this is the very place for the poor student … whose needs are peace and a short distance from the British Museum. There is hardly anybody about … there are no shops here to draw people; there is deep,

leafy silence.

For trees grow everywhere in this happy place. They lean over garden walls, they congregate together in hushed squares, they swell richly from little patches of odd ground, from behind railings, in every unexpected corner, and there are short flights of steps which lead to mysterious alleys or passages or byways going to nowhere in particular; here, too, you shall find unexpected ash groves and sweet quivering poplars and little houses strangely tucked away. Here is no jangle of the tram, here no motor-'bus snorts and rattles as the gear is changed. In half an hour's walk I saw neither taxi nor car of any sort; for the storms of our age do not beat upon this place. (fn. 21)

Later, in the 1920s, the architect George Llewellyn Morris also found much to appreciate, not just in a more considered analysis of the area's architecture, novel enough at this date, but also in the outdoor social life of Wilmington Square on a Saturday, though he did not fail to see poverty too. (fn. 22)

Again, perspectives differed, and others could not see beyond poverty. In Riceyman Steps (1923) this was not a happy place. Arnold Bennett noticed 'squalor and foulness', and Riceyman Square, based on Granville Square, was 'decrepit, foul, and slatternly'. A decade later the board game Monopoly bestowed lowly status on Pentonville Road and the Angel. Bomb damage followed, and after the war Harold Clunn found the area north of the Pentonville Road—with the exception of Chapel Market—'a scene of great desolation', with a large slum-clearance area flanked by bombsites. (fn. 23)

For the journalist and folk-singer Bert Lloyd in 1951, Pentonville was a place of vigour, 'one of the last atolls of the old-time cockney life'. His eyes found solace in the townscape around Chapel Market: 'these have not the forlorn abandoned look of many London back streets. Something of the old elegance stays with them in the cut of a doorway or the harmony of a terrace-row. The face may be smudged but the air is still there. They are streets of character, lived in by people of character'. (fn. 24)

By this time the roots of that character had grown deep. Working-class people had not only the houses, but also well-established street markets, chain stores, pubs, cinemas and other entertainments. Chapel Street had been a market since the 1860s, and Exmouth Street was quickly adapted as another once Rosebery Avenue freed it from heavy traffic in 1892. Name changes formalized these markets in the late 1930s. Among the earliest of all Sainsbury's shops was that opened on Chapel Street in 1882, and other multiples were quick to target the area's population; the Marks and Spencer on Liverpool Road originated as a penny bazaar in 1914. From 1896 Frank Job Chambers's patent iron shopfronts popped up as a 'cheap and temporary' presence on awkward small plots along Rosebery Avenue. A number are still in place. Manze's stewed-eel and pie house, opened in 1898 at No. 74 Chapel Street, is another survival, as is Clark's at No. 46 Exmouth Market, originally run by the Manze family in the 1930s.

Pubs, some of which traced their origins back to the spas, continued to thrive and were sometimes rebuilt on an ambitious scale. That does not imply local prosperity (quite the reverse), but it does counter an impression that the place had become a desert. From the Coach and Horses on Ray Street and the London Spa of 1897–8 northwards to the White Lion and the Angel of 1898 and 1903 respectively, there are buildings of some exuberance. In later times this spirit was contained, and there were nods in the early 1920s towards temperance in the shape of the 'family café' at New Merlin's Cave and the conversion of the Angel into a Lyons' Café. A decade later there was a harking back to the days of inns at the neo-Tudor Pied Bull, but the sobriety of neo-Georgian became more usual. By the 1950s the area's pubs were much reduced in number.

Pre-eminent among local places of entertainment was Sadler's Wells, which in 1844 had been revived as a Shakespearean theatre. It staggered on precariously through the Victorian period, with Deacon's Music Hall opposite. Use as a music hall and cinema came and went; around 1900 the 'Wells' was a popular local refuge, its social character indicated by a stall selling two-a-penny boiled pigs' trotters. (fn. 25) After a period of closure and dereliction Lilian Baylis and others rebuilt it as a 'people's theatre' in 1930–1.

Around 1910, when cinema-going became more a necessity than a luxury for London's working class, several purpose-built premises arrived. (fn. 26) The grandest of these was the Angel Picture Theatre of 1911–13, an initiative by Abraham Davis whose high-minded purposes were realized through the formation of the Social Service Educative Entertainment Co. Ltd. The cinema has gone, but its tower, never functional other than as a landmark, survives on Islington High Street.

There had been many other well-meaning initiatives aimed at Clerkenwell's working-class population, not least the opening of churches, missions and schools; these are dealt with in the introduction to volume xlvi. Mention must also be made of another important phenomenon—redevelopment with factories and other purpose-built commercial premises. From the 1890s to the 1930s much of Rosebery Avenue, particularly the middle stretch, was given over to such buildings, and through the same decades Pentonville Road was much transformed for all manner of manufacturing and warehousing. Lewis Solomon and Herbert Wright were the architects most often employed. Given the state of the housing market, the landowning estates preferred commercial to residential use of their property in the years around 1930, and government planners also saw Finsbury's future as commercial. Domestically based industries were now in acute decline, though some trades survived through expansion into purpose-built premises. Easton Street was all but wholly redeveloped in the 1920s and 30s, for metal spinners, boiler makers, razor-blade makers and printing-ink manufacturers; and the Temple Press, which had been based on Rosebery Avenue, built itself huge premises between Bowling Green Lane and Northampton Road in 1938–9. After the war, housing became a priority, and the London County Council and Board of Trade combined to prevent further industrial development in Finsbury.

Public amenities and housing up to the 1930s

Despite being exposed in the 1880s as supine and self-serving, Clerkenwell Vestry had not been entirely inactive during the later nineteenth century in trying to ameliorate social conditions. In the 1860s drinking fountains were put up here and there, and a 'make-belief garden' was formed on the site of Spa Fields burial ground, where a mortuary was also built in 1876. Open spaces were scarce and that problem was addressed in the immediate aftermath of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes. In 1885 the gardens at Northampton Square and Wilmington Square were made over to the public through the privately funded Metropolitan Public Gardens Association. These gardens were closed to unaccompanied children, so the MPGA also made the former burial ground a children's playground. Efforts were made a few years later to secure part of the Middlesex House of Correction site at Mount Pleasant as more public open space. Instead, the entire site was used for a vast postal sorting office, and the London County Council created Spa Green Gardens near by, alongside the new Rosebery Avenue. Ground cleared for the creation of Rosebery Avenue at the west end of Exmouth Market was acquired by the Vestry as an open space. The MPGA also took on the churchyard of St James's, Pentonville, making it into a public garden.

There were other manifestations of a new civic optimism. In 1890 the Vestry built Clerkenwell Free Library, the first public library in Britain to adopt the open-access system; and from 1893 it put up a new home for itself, replacing the 'smallest and worst Vestry Hall in London' with the picturesque building on Rosebery Avenue that soon became Finsbury Town Hall. An architectural lead for this had come from E. W. Mountford's bold Northampton Institute, across St John Street, which brought first-class facilities for technical education and recreation to Clerkenwell's young people.

However, suburban flight was reducing their numbers significantly. From a peak of 65,380 around 1881, Clerkenwell's population had declined by 1911 to 57,121—a fall of 17 per cent—to a level close to what it had been in 1841. Even so, there were still places with high densities, and while the population decreased further, so did the number of houses, as land was given over to purely commercial use. In the 1930s Finsbury, despite its population having all but halved since 1901 (metropolitan decline exceeded only in the City), had the most acute overcrowding of any London borough, with 'bad patches' to the south and north of what remained 'the best residential district', immediately south of Pentonville Road. (fn. 27)

Housing was thus a matter of abiding public concern. The LCC built Mallory Buildings on St John Street in 1904–6, but was otherwise inactive as a housing provider in Clerkenwell in its early years. Another special initiative, a philanthropic venture, was the Mary Curzon Hostel for Women of 1912–13 on King's Cross Road. During the first quarter of the century housing was still generally left to the landowners, to improve or not, with little external engagement. There were several reasons why Finsbury Council was slow to pick up the baton of housing improvement: little ground on which to build, little money available to do so, and, of course, war. Afterwards, in 1919–20, the Northampton Estate offered the council sites for building, but it could not afford or was not prepared to buy them. A primary restraint was the legislative framework which, until 1930, provided neither subsidies nor ways round the re-housing implications of slum clearance. But this was a general problem. Locally, the political climate was not, in any case, conducive to action. A presumption on the part of central government and landowners in favour of commercial redevelopment in Finsbury was a deterrent, and from 1906 to 1928 the council was controlled by those allied to the Conservatives, Municipal Reform and the Ratepayers' Association. The borough's first Labour MP was elected in 1923, and its first Labour administration only came five years later.

The years around 1930 were Finsbury's first golden age of municipal building. A Maternity and Child Welfare Centre was built on Pine Street in 1926–7, and in the same years the council built Grimaldi House and Mandeville Houses in Pentonville, following adjacent Islington Council's example in both its approach to housing and its employment of E. C. P. Monson as architect.

In 1930 Finsbury Council, led by Alderman William Martin, acquired three largely cleared acres between Margery Street and Lloyd Baker Street. There it built the Margery Street Estate, completed in 1933, with Monson as architect. A statement of intent by Finsbury's first Labour administration, the first phase, unusual for being mostly maisonettes, was built to far higher specifications than those countenanced by the LCC, particularly as regards space allocation. This inevitably landed the council in trouble. As the site had already been cleared it did not qualify for central-government slum-clearance subsidies, and, in a clash between aspiration and accountancy that was to recur, the District Auditor forced a scaling back of standards in the later blocks along Lloyd Baker Street, built after the Ratepayers returned to power in 1931. That one of these blocks was named Riceyman House seems remarkable, given Bennett's unfavourable picture of just a decade earlier.

Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Police had built Charles Rowan House near by in 1928–30, to provide flats for nearly a hundred married policemen, the joint largest such concentration in London. The council took a site to the south for the Merlin Street municipal baths of 1931–3, Clerkenwell's first. Out of doors, the garden at Holford Square was made into a public bowling green in 1934 (a revival of one of the area's historic amenities, and the only municipal facility of its kind in central London), and work on the new Spa Fields Recreation Ground began in 1936.

It was in the years before, during and immediately after the Second World War that Finsbury gained renown for a radical and socially progressive attitude to public health and housing provision, through a series of high-profile modernist projects designed for the borough by the architectural practice Tecton, led by Berthold Lubetkin. Their significance calls for discussion here in some detail.

The contribution of Berthold Lubetkin and Tecton

The schemes of radical architecture planned and carried out for the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury between 1935 and 1958 by the practice of Lubetkin and Tecton and its successor-firm, Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin, have an abiding place in the annals of British modernism. These projects, their reforming agenda and the unorthodox partnership built up between Berthold Lubetkin and the borough are here set against the local backdrop. For an account focusing upon the art and personality of the dynamic Lubetkin, readers are referred to John Allan's meticulous biography of that architect. (fn. 28)

Four major projects were planned and realized for Finsbury under Lubetkin. The first and smallest of these, the Finsbury Health Centre, was followed by two large flatted estates of council housing, ultimately known as Spa Green and Priory Green, planned before the Second World War but executed after it in altered circumstances. After them came a final post-war housing estate, consisting of Bevin Court with two small outliers. In addition, in 1938–9 Lubetkin and his colleagues devised an unofficial planning project for the borough known as the Finsbury Plan, and were involved in the championing of deep air-raid shelters which drew Finsbury into a confrontation with official government policy. During the war, Lubetkin personally designed the short-lived Lenin memorial installed in Holford Square in 1942.

Though one other housing scheme was mooted, no new commissions came to Lubetkin from Finsbury after 1950, by which time he had largely withdrawn from professional prominence, though not from active practice, having formed a new working relationship with Francis Skinner and Douglas Bailey. Most of that partnership's later housing work was carried out for the borough of Bethnal Green.

Lubetkin's association with Finsbury began in 1935, some three years after he had founded his group-practice of Tecton. On the strength of an ideal project for a tuberculosis clinic, the firm was identified by the chairman of the Public Health Committee, Dr Chuni Lal Katial, as potential architects for the new health centre he was promoting. The Labour Party had not then long returned to local power. In response to Finsbury's grave deficit in health and housing, it was embarking on an accelerated version of the reform agenda that had marked its first term of office.

Katial (1898–1978) was Lubetkin's original client and ally in Finsbury. Originally from the Punjab, he had only recently moved to the area. He settled in London about 1929, at first running a medical practice in Canning Town, where he brought Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin together during the former's London visit of 1931. (fn. 29) Though health was his initial concern, he was also on Finsbury's Housing Committee. So it was to Katial and the Town Clerk, Arnold James, that Lubetkin first suggested modern flats for the borough, soon after his appointment to the health centre in 1935. A new Housing Act of that year directed local authorities to survey and tackle overcrowding. Finsbury was keen to act, but Katial told Lubetkin in March 1936 that an overture to Tecton then would be 'too early', as the London County Council was interested in building itself: 'I explained that we would like to have a go on it as LCC not always up to date', Lubetkin noted. (fn. 30)

Two months later James conferred with him about a possible ten-storey block or blocks with lifts, probably for a site at the corner of Pentonville Road and St John Street. (fn. 31) It came to nothing, but in October 1936 there is the hint of a site in Southampton Street (about then to become Calshot Street), Pentonville. (fn. 32) That appears to mark the start of the grandest of Lubetkin's engagements for Finsbury, the Busaco Street housing scheme, eventually Priory Green. Once Tecton were appointed to rebuild the Busaco Street slum in Spring 1937, intensive research on sociology and planning followed, led by Lubetkin's partner Francis Skinner. (fn. 33) It bore fruit in the first of the long, detailed reports that accompanied each major stage of Tecton's oft-revised housing propositions for Finsbury. (fn. 34)

From the start, Tecton's housing designs embodied higher standards of accommodation and facilities than were usual in British council housing, and were replete with technical and social novelties. But Lubetkin and his young architect-colleagues were by no means enlightening a hitherto benighted borough. The generosity of provision at Margery Street was, in fact, a hard act to follow; maisonettes were not here a novelty. Nevertheless, the intensive focus on the planning and servicing of flats, palpable from the start of Tecton's Finsbury projects, was new.

So too was the structural thinking in all the schemes, the Finsbury Health Centre included. That entailed an evolving collaboration with the engineer Ove Arup. Until 1938 Arup was an employee of J. L. Kier & Co., the concrete subcontractor for the health centre and, after the war, for Spa Green and Priory Green. After Arup left Kiers to set up a consultancy, he and his colleagues worked up the ingenious concrete structure of the two estates in that capacity. The main novelty in the estates as built was the concrete 'box frame', whereby continuous cross walls and floor slabs replaced a skeleton frame or a structure with load-bearing external walls. That method, so it was argued, would avoid the obstruction of beams and columns within the building, and release the main façades to find their own expression and lively patterning in Lubetkin's hands.

The box frame, though influential and much publicized, took time to establish. The 1938 design for Busaco Street (Priory Green) was premised on some kind of concrete skeleton frame with infill panelling; and when Sadler Street (Spa Green) was revived in 1943, the initial idea there was to give it solid external walls, like Highpoint One (1933–5), the former of the two famous blocks of luxury flats at Highgate in which Lubetkin and Arup worked out new ways of planning and erecting tall apartment buildings. Not until 1944, when Arup wrote a memorandum setting out the principles of the box frame, as he christened it (in America it was usually termed egg-crate construction), was this method developed into a general construction system for tall flats. Spa Green marked its first large-scale trial, and Priory Green continued it. (fn. 35) In the event, the process of building the two estates did not prove totally successful. Partly for personal and partly for practical reasons, Lubetkin abandoned Arup for his final Finsbury project, Bevin Court.

Lubetkin and Tecton were acutely aware of the publicity potential of their pre-war designs in furthering a socialist agenda for reform. One early Tecton memorandum on Busaco Street is marked 'Propaganda re Council Elections'. (fn. 36) The scheme was indeed first published by the Finsbury Labour Party in their organ, the Finsbury Citizen, in advance of the elections of November 1937, at which Labour was again returned. Also mentioned there as an earnest of the Council's zeal in rehousing was the smaller Sadler Street clearance scheme between Rosebery Avenue and St John Street, later Spa Green. (fn. 37) Sadler Street had not yet then been assigned to Tecton, but they were confirmed as its architects in 1938 after the election. Thereafter the two schemes' progress was entwined, though Spa Green had the happier subsequent history.

At the political level Tecton's housing projects were championed by Harold Riley, leader of Finsbury Council from 1934 to 1945 and at first the chairman of its pre-war Housing Committee. Over time, Lubetkin's plans for the borough became bound up with Riley's rise and fall. Riley had been Labour's parliamentary agent in Finsbury since 1922 and masterminded the party's local election victories in 1934 and 1937. (fn. 38) His uncompromising socialism chimed with Lubetkin's own ardent nature. In both of them the instinct for leadership could turn into truculent independence.

A hint of that came in January 1939, when the Architectural Review prefaced its publication of the Finsbury Health Centre with a brief article called 'Finsbury Makes a Programme'. There Tecton analysed the social composition of the borough and sketched out a plan for distributing modern public services, mostly health facilities and air-raid shelters. (fn. 39) This so-called 'Finsbury Plan' had no official status and went no further as a whole; Allan suggests it may have been an 'operation codename' used privately by Lubetkin and Riley for their longer-term intentions. (fn. 40)

The air-raid component, however, was real and active. Following the Munich crisis of September 1938, Tecton were appointed by Finsbury to survey the borough and make 'a comprehensive report upon the measures necessary to be taken for affording protection to the civil population from hostile attack from the air'. (fn. 41) Lubetkin and his colleagues relished that type of broad research project, and tackled it with address. The report, issued in February 1939, recommended a complete local survey of existing basements which could be used for ARP purposes. It was followed by a second in which Tecton, working with Ove Arup, advocated the provision of fifteen deep underground shelters across the borough, at a cost of well over a million pounds. The effective publicity attracted by this plan annoyed the Government, which had opted for a policy of dispersal combined with light shelters. Experts and politicians were therefore invoked to condemn Finsbury's scheme. (fn. 42)

After the initial controversy Lubetkin took limited interest in the ARP battle. But Riley was not to be deterred from translating his propaganda triumph into action. The sequence of ensuing events on Finsbury Council has been studied by the late Catherine Steeves, though the following summary departs in some particulars from her interpretation. (fn. 43) Acting ultra vires, Riley and Arnold James committed council expenditure to embarking on the first of the projected deep shelters at Busaco Street in the summer of 1939. Though it did not get far, the gesture was sufficient to bring surcharge and disqualification upon Riley and James four years later. The Garnault Place Control Centre, a two-storey bunker under Finsbury Town Hall, was built to Tecton's designs in 1939–40; it survives as a disused space, and a reminder of this saga.