Pages 368-392

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

SWYNCOMBE

Swyncombe lies in the Chiltern hills c.5 km south of Watlington and 11 km north-west of Henley-on-Thames. (fn. 1) Settlement is scattered amongst the hamlets of Cookley Green, Park Corner, and Russell's Water (which lies mostly in Pishill), and the population has probably never exceeded its mid 19th-century peak of 446, when all but a few households worked in the parish's woods, farms, and brick industry. More recently the parish's typical Chiltern setting has attracted affluent commuters working in professional and managerial occupations. Swyncombe House (the former manor house), adjoining the church in what is now a secluded location, was occupied from the 16th century by minor gentry, but burned down in 1814 and has since been twice rebuilt. Ewelme park in the south of the parish, originally a medieval deer park, acquired a much larger mansion house in the earlier 17th century, but that too was demolished within a few decades, and replaced only in 1913.

PARISH BOUNDARIES

In the late 19th century the ancient parish covered 2,708 a., forming a relatively compact block. (fn. 2) Parts of the boundary followed early routes, notably Icknield Way in the north-west, sections of roads linking Britwell Salome, Russell's Water, and Watlington in the north and north-east, and Digberry Lane on the south. (fn. 3) The eastern boundary with Bix and a detached part of Ewelme traced a less regular course through woods and fields, while the south-west boundary near Ewelme park partly followed the contours of Harcourt Hill. From there the boundary ran northwards across the downs to rejoin Icknield Way, leaving the Chiltern foothills (Ewelme Downs) within Ewelme parish.

The northern and eastern boundaries coincided with those of the hundred, which were established before the Norman Conquest and possibly by the 9th or 10th century. (fn. 4) Elsewhere the boundaries derived presumably from those of the local estates carved from Benson before and after the Conquest, amongst them the 2½-hide Swyncombe manor, which existed by 1086, possessed a church soon after, and probably covered most (though not all) of the later parish. (fn. 5) Adjustments may have followed the relatively late creation of estates in neighbouring Nettlebed and Nuffield and the creation of Ewelme park, (fn. 6) but otherwise the parish's boundaries were probably broadly established by the 12th or 13 th century.

In 1952 the parish absorbed 868 a. from Bix, including woods, farms, and houses at Maidensgrove, bringing the area to 3,576 a. (1,447 ha.). (fn. 7) Around 20 a. (8 ha.) in the south-east were transferred to Bix in the early 21st century. (fn. 8)

LANDSCAPE

The parish extends from the scarp to the summit of the Chiltern hills, and lies mostly on chalk, capped along the ridge by a mantle of clay-with-flints. The relief is uneven, and from Cookley Green (at 224 m. almost the highest point in the parish) the land falls north-westwards to 140 m. at North Farm and 111 m. near Warren Bottom in Ewelme, giving spectacular views across the vale. In between, the deep dry coombs of Swyncombe Downs create a secluded and intimate landscape typical of the Chilterns (Plate 1), although one generally more wooded from the late 19th century than earlier. (fn. 9)

The church and manor house lie at c.160 m. in a sheltered hollow (Fig. 104), from which the ground rises southwards to a plateau of c.200–215 m. at Park Corner and Ewelme park. Remnants of the wooded parkland survived in the 19th century, when tree stumps marked parts of the parish boundary amidst open arable closes, while 20th-century plantations (including larch and conifers) provided more modern coverts for fox-hunting and shooting. (fn. 10) As elsewhere in the Chilterns, tanks and wells were the only water source until piped supplies became available by the 1930s. (fn. 11)

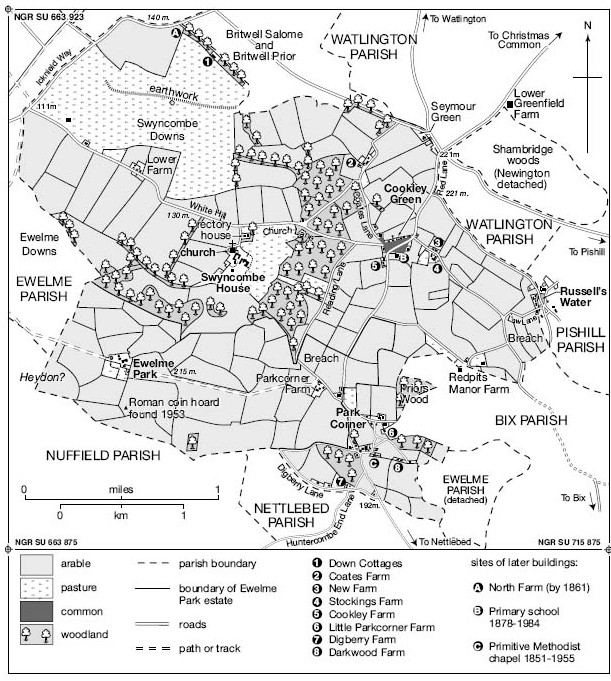

Swyncombe parish in 1839, showing boundaries, land use, and some later buildings.

COMMUNICATIONS

The ancient Icknield Way, running along the foot of the Chiltern scarp, (fn. 12) marked the parish's north-western boundary, while the Roman road from Dorchester to Henley probably crossed its south-western corner near Ewelme park, continuing roughly along the line of Digberry Lane between Swyncombe and Nettlebed. (fn. 13) From the Middle Ages the chief route through the parish ran north–south from Watlington to Nettlebed, partly along a ridgeway called Red Lane, from the colour of the subsoil. The hamlets of Cookley Green and Park Corner both developed alongside it, (fn. 14) and in the 1230s the stretch near Digberry Farm was apparently called Reading way. (fn. 15) Branch roads included parallel north-south routes called Coates Lane and Reading Lane, the east-west Church Lane and White Hill (which joined Icknield Way), a medieval road to Bix with a link (Law Lane) to Russell's Water, and a track to Ewelme park, which continued along the Ewelme–Nuffield parish boundary. (fn. 16) All those survived in the early 21st century as unnumbered roads or bridleways, connected by a dense network of footpaths; the Watlington–Nettlebed road (the modern B481) remained, however, the most important through–route. (fn. 17)

A carrier from Watlington to Reading passed through the parish on Saturdays in the mid 19th century, while a service from Park Corner (operated by the local Hayes family) ran to Henley on Thursdays (market day), continuing until the 1890s. (fn. 18) Thereafter inhabitants presumably used carriers from Nettlebed and Watlington. (fn. 19) Motorized buses ran between Watlington and Reading from the 1920s, (fn. 20) and an occasional service from Cookley Green and Park Corner continued in 2011. Post was delivered from Nettlebed in the 19th century, and later from Henley. A sub-post office at Park Corner opened in the 1850s, managed first by the blacksmith Stephen Wixen, in the 1860s by the farmer John Parker, and by women from the 1880s; a post and telegraph office at Cookley Green succeeded it in the early 20th century, (fn. 21) continuing until 1967. (fn. 22) A second sub-post office at Russell's Water was short-lived. (fn. 23)

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

Prehistoric to Anglo-Saxon Settlement

Flint axes and other implements of Mesolithic to Neolithic date have been found on the northern, east-ern, and western edges of the parish, together with a probably Bronze-Age flint dagger tip. (fn. 24) On the southern boundary with Nettlebed prehistoric enclosures and other features have been identified from cropmarks, (fn. 25) and in the north a prehistoric ring ditch lies next to Icknield Way. (fn. 26) A late 3rd-century Roman coin hoard discovered along the Roman road south of Ewelme park may indicate passing traffic rather than settlement, although Roman occupation is known in the vicinity. (fn. 27) Two significant earthworks remain undated, one of them a boundary dyke running along the northern edge of the downs for about a mile, and commanding Icknield Way. Sherds of Iron-Age pottery have been found nearby. (fn. 28) A massive square enclosure at Digberry Farm is equally enigmatic. (fn. 29)

Anglo-Saxon exploitation is reflected in the parish's place names. Swyncombe means swine valley (the element cumb being particularly characteristic of the Chilterns), while Cookley is probably Cue's lēah (or wood-pasture), incorporating the same personal name as nearby Cuxham. Several field names also include Anglo-Saxon elements. (fn. 30) Park Corner was known in the 18th century as Stanley or Stanvill, the Anglo-Saxon stān referring presumably to the area's abundant flint. (fn. 31)

Population from 1086

No tenants were recorded on the manor in 1086 when it was presumably administered as demesne, although the late 11th-century church suggests a small resident population. (fn. 32) Around 26 tenants were named c.1248, and in 1279 there were 10 serfs (servi) and 11 cottars, suggesting a total population of 80–100. (fn. 33) Seven people including the prior of Bec (as lord) paid tax in 1306, but mid 14th-century plague seems to have had a serious long-term effect, since in 1377 only 16 adults aged over 14 paid poll tax. (fn. 34) In 1524 the parish was taxed with places in Nuffield, and few Swyncombe people contributed to the lay subsidies of the later 16th century. (fn. 35)

Thereafter the population rose slowly, with baptisms usually outnumbering burials. (fn. 36) Thirteen households were assessed for hearth tax in 1662, 90 adults were mentioned in 1676, and a population of c.200 was reported in 1718, (fn. 37) the estimated number of houses rising from 40 in 1738 to 50 in 1759, and to 55 in 1771. (fn. 38) By 1801 there were 53 occupied houses and a population of 285, rising to 70 houses and 367 people thirty years later. The population peaked at 446 in 80 houses in 1861, falling to 308 (in 72 houses) by 1891. During the 20th century the population fluctuated between 342 (in 1901) and 280 (in 1981), the number of households rising from 79 to 102 over the same period. In 2011 a total of 250 people occupied 106 houses. (fn. 39)

Looking south-east to Swyncombe church (centre bottom), Swyncombe Home Farm, and Swyncombe House, set in a hollow amidst the tree-covered Chiltern slopes. The former rectory house is at bottom left.

Medieval and Later Settlement

As elsewhere in the Chiltern uplands, medieval settlement was dispersed (Fig. 103). The origins of individual hamlets and farmsteads are generally untraceable, although some must have existed by the late 11th century when the present church was built. Any tenant housing next to the church was probably removed in the 16th or 17th century when the manor house was rebuilt by resident lords, (fn. 40) and in the early 18th century around half the parish's 40 houses were at Park Corner, with a further eight at Cookley Green and the same number at Russell's Water, the rest of which lay in Pishill parish. The houses at Cookley Green and Park Corner were arranged around small greens, (fn. 41) while a few additional cottages were built on the edges of commons or in the woods. (fn. 42) A lodge in Ewelme park existed probably from the park's creation in the 14th or early 15th century, and in the early 17th century was briefly superseded by a short-lived but exceptionally large mansion house. Coates (or Bacon) Farm (north of Cookley Green) was established by the 16th century and possibly in the Middle Ages, (fn. 43) while small-scale medieval settlement at Heydon may have straddled the western boundary with Ewelme. (fn. 44)

In the mid 19th century Park Corner (including Digberry Lane) remained the largest hamlet, containing c.25 of the parish's 80 houses. Cookley Green and Russell's Water each contained c.18 households, while the remainder lay dispersed at Swyncombe House, the rectory house, Ewelme park, Lower Farm, Coates Farm, Seymour Green, and Down Cottages (on the Britwell Salome boundary). (fn. 45) Cookley Green was the site of the schools, though other foci (including pubs, shops, and chapels) remained divided between there, Park Corner, and Russell's Water. (fn. 46) The settlement pattern remained largely unchanged thereafter, the number of houses increasing to only 85 until the boundary changes of 1952. (fn. 47) Subsequent decades witnessed relatively little new development. (fn. 48)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Swyncombe's vernacular buildings are broadly typical of the Oxfordshire Chilterns. Farmhouses and cottages of outwardly 17th- to 19th-century date are thinly scattered throughout the parish, built mostly of brick, flint, and clay tile. Though varying in size and style, none (with the exception of Swyncombe House and Ewelme Park) (fn. 49) stands out as particularly distinctive. The early 18th-century Park Corner Farm, flint-built with brick quoins and dressings, brick stacks, and a tiled hipped roof, is typical of the better tenanted farmhouses. Two-storeyed with attic gables, it has a three-bay front and a double-pile plan, its rooms lit by windows with 19th- and 20th-century sashes and casements. (fn. 50) In the 19th century it was covered with ivy, and its enclosed yards included brick and timber barns, stables, and sheds, variously roofed with tile, slate, or thatch. (fn. 51) Later outbuildings used 'iron and other materials'. (fn. 52)

On the same estate the 18th-century Ewelme Park Farm, of rendered brick with a tiled gabled roof, (fn. 53) was superseded in the late 19th century by a larger brick and slated residence. The original farmhouse was subdivided for use as labourers' accommodation, supplementing several tied cottages which were let on service tenancies into the mid 20th century. (fn. 54) On the Swyncombe manor estate, the 17th-century Home Farm was extended and remodelled in the 19th century, though the flint, brick, and tile of its main ranges remained wholly characteristic. (fn. 55) Among the estate's farm buildings, the 17th-century aisled barn of four bays with a queen-post roof at Coates Farm is particularly impressive. Built on a brick and flint base, it is weatherboarded with a tiled roof. (fn. 56) Timber and thatch were probably once more common on both estates, and at Lower Farm were used in the barns and stable mentioned in the late 18th century. (fn. 57)

Other 18th-century farmhouses include Darkwood and Little Parkcorner (or Chear's) Farms, built in different styles but using the same materials of brick, flint, and tile. Decorative features at Little Parkcorner Farm include segmental brick arches over windows and door, while Darkwood Farm has a notable M-shaped gabled roof. (fn. 58) Such buildings reflected the widespread agricultural prosperity of the period, when the profits of farming enabled landowners to replace the small, old-fashioned houses mentioned in mid 17th-century hearth taxes and inventories with more modern and comfortable residences. (fn. 59) Rebuilding also extended to many of the parish's cottages, of which several were newly built or substantially enlarged in the 18th century. (fn. 60)

The number of inhabited houses rose from 53 in 1801 to 80 in 1851, although the increase did not always keep pace with population: in 1831 some 88 families were accommodated in only 70 houses. (fn. 61) Like the earlier buildings most were of brick and flint and were unexceptional, and at the beginning of the 20th century many still belonged to the parish's major landowners. (fn. 62) By then population was falling, leaving houses vacant: twelve in 1881, eight in 1891, and six in 1901. (fn. 63) A few council houses were built at Park Corner in the 1920s, and private development in the 1970S–80S raised the number of households from 95 to 113. Nonetheless the parish's built character remained substantially unchanged. (fn. 64)

MANOR AND ESTATES

What became Swyncombe manor was separated from Benson before the Norman Conquest, when it was assessed at 2½ hides. (fn. 65) Probably it included most of the later parish, with the exception of a few medieval freeholds, some holdings at Cookley Green, and possibly some woodland, which until the 1620s belonged to Ewelme or Benson manors. (fn. 66) Ewelme park in the south (created in the 14th or 15th century) became an independent estate in 1627, and in 1839 covered c.620 a., just under a quarter of the parish. Swyncombe manor then covered 1,600 a., and three freeholds (possibly all of medieval origin) 310 a., two of them remaining in separate ownership in 1910. (fn. 67) Bec abbey established a manor house by the 13th century on a site still occupied in 2015, while a short-lived 17th-century mansion for Ewelme park was succeeded by a new country house in 1913. (fn. 68)

SWYNCOMBE MANOR

In 1066 Swyncombe may have belonged to the prominent royal official Wigod of Wallingford, passing after the Norman Conquest to Miles Crispin. (fn. 69) Before 1086 Miles and his mesne tenants (Hugh fitz Miles and Richard fitz Rainfred) granted it to the Norman abbey of Bec, which held it until its confiscation in 1404 during the wars with France. (fn. 70) In 1410 the king confirmed its grant by Thomas Langley, bishop of Durham, to John, later duke of Bedford, (fn. 71) who probably sold it to Thomas Chaucer (d. 1434) and his wife Maud (d. 1437), the owners of neighbouring Ewelme. (fn. 72) Thereafter the manor passed with Ewelme to the de la Poles, until both estates were seized by the Crown in 1501. (fn. 73)

In 1519 the king leased Swyncombe to Anne Broke (d. 1532) and the courtier Henry Norris, (fn. 74) and in 1525 granted the reversion (with Ewelme) to Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk, and his wife Mary, the king's sister. (fn. 75) In 1534 Brandon leased Swyncombe to his treasurer Thomas Carter (d. 1551) for 40 years, before returning both manors to the Crown in 1535 in return for lands elsewhere. (fn. 76) In 1565 Elizabeth I granted reversion of the lease to John Fortescue, master of the wardrobe, for 21 years from 1575, renewing the grant in 1582 and 1591 for a further 60 years. (fn. 77) Fortescue was succeeded in 1607 by his wife's nephew Sir Edmund Fettiplace (d. 1613), whose successor (his nephew Francis Fettiplace, d. 1671) bought the manor from the Crown in 1627. (fn. 78)

Francis's son Bartholomew Fettiplace (d. 1686) was succeeded by three daughters, among whom the manor was divided. In 1694 it was reunited in the possession of Katherine Fettiplace's husband Charles Dormer (d. 1728), whose son sold it in 1732 to Samuel Greenhill (d. 1754). (fn. 79) Greenhill's son sold it in 1758 to George Ruck (d. 1763), whose daughter Mary married Benjamin Keene (d. 1837). (fn. 80) Keene was succeeded by his second son, Revd Charles Ruck Keene (d. 1880), by Charles's son Edmund (d. 1888), and by Edmund's son Charles (d. 1919). (fn. 81)

In 1921 trustees for Charles's daughter Betty sold the manor to Sir Charles Cottier (d. 1928), and in 1929 it was bought by Charles Christie-Miller (d. 1976), (fn. 82) whose son (William) John (d. 1999) rebuilt Swyncombe House. Following the death of John's widow Kathleen in 2004, the house and most of the estate passed to his nephew Samuel Fielden, save for a smaller part held in trust by Stephen Christie-Miller. (fn. 83)

Manor House (Swyncombe House)

Bec abbey's manor house or curia was mentioned in 1279, and accommodated the abbey's officers along with visiting monks. (fn. 84) In 1324 it was worth 35. a year with its curtilage, garden, and dovecote. (fn. 85) The house was probably occupied by Anne Broke in the 1520s and Thomas Carter in the 1540s, (fn. 86) but in the mid 16th century it was 'ruined and in decay', and may have been rebuilt or remodelled by Thomas's son Brian, who was given oak and beech timber by the Crown. (fn. 87)

Swyncombe House before its destruction by fire in 1814.

The building survived until 1814 when it was destroyed by fire. A sketch (Fig. 105) based on an earlier drawing shows a two-storeyed main range of seven bays with twin-gabled attics, suggesting 17th-century remodelling. An elaborate, probably 16th-century two-storeyed porch with an arched entrance occupied the right-hand bay, and was elaborately decorated with pilasters, a frieze, and heraldic devices, some of them reportedly associated with the Brandons. Horizontal string courses marked the first and attic floors, while five corkscrew-shaped stacks surmounted an apparently tiled roof. Further large ranges to the rear incorporated a rounded, possibly medieval corner turret. (fn. 88) In 1662 the house was taxed on twelve hearths. (fn. 89)

A successor, built c.1840 for Revd Charles Ruck Keene, was of red brick in a Jacobean style (Fig. 106). The entrance front faced south-east and included three shaped gables, a central porch beneath an oriel window, and flanking four-light mullioned-and-transomed windows to the ground floor. Above a string course were similar three-light windows to the first floor, with two-light mullioned windows to the attics. The string course continued to the north front, where five narrow bays with similarly shaped gables were lit by two- or three-light mullioned-and-transomed windows. The roof bristled with numerous tall stacks. (fn. 90)

In 1978 permission was given to demolish the house, which was replaced by a smaller residence in Georgian style; one of the architects was the interior designer David Hicks (d. 1998). Of red brick with stone quoins, it has five bays, two storeys, and a hipped roof and tall end stacks. A central doorway with a wrought-iron porch is flanked by six-over-six sash windows, with five similar windows to the floor above. (fn. 91) As earlier, the former home farm's farmhouse and extensive farm buildings adjoin to the north-west (Fig. 104).

OTHER ESTATES

Ewelme manor included holdings at Cookley from the Middle Ages until 1627, when the manor was sold off in parcels. (fn. 92) From the early 15th century the newly created Ewelme park also descended with Ewelme, until its sale as a separate estate in the 17th century (below). Freeholds at Heydon (on the Ewelme boundary) were mentioned in the 13th century, (fn. 93) and Coates Farm near Cookley was named probably after the freeholder Ralph de Cotes, who married the daughter of another freeholder, Maurice de Swyncombe (d. before 1219). (fn. 94) Wallingford priory owned Prior's wood on the parish's eastern edge, (fn. 95) while Benson manor retained a small woodland parcel at Cookley in 1606. (fn. 96)

Three freeholds recorded in 1839 may have also been of long standing. Thomas Cottrell owned 188 a. at New farm in Cookley Green, part of an estate focused on Redpits (in Bix) which was mentioned from the 16th century. (fn. 97) Thomas Toovey, one of a long-standing local family which provided one of Swyncombe's 18th-century rectors, owned Little Parkcorner and Digberry farms (51 a. in total), but lived at Joyce Grove in Nettlebed. (fn. 98) Darkwood farm and land at Park Corner (67 a.) were owned by John and Charles Parker, whose estate was later incorporated into Swyncombe manor by Revd Charles Ruck Keene. (fn. 99)

Ewelme Park

Ewelme park (later Ewelme Park farm) lay in the south of the parish, bordering Ewelme and Nuffield. A park belonging to Bec abbey, recorded in 1314 when a tenant was caught grazing his pigs there, was possibly in the same area, (fn. 100) but if so it was extended before 1440, when the 'new park called Heydon park' stretched from the parish's western boundary presumably as far as Park Corner. (fn. 101) Probably the new park was created by Thomas Chaucer (d. 1434), who had recently acquired Swyncombe manor, and was known to contemporaries as a lover of hunting. (fn. 102) Charles Brandon enlarged it further in the 1520s–30s, adding another part of Heydon Ground. (fn. 103) From 1535 it reverted to the Crown with the rest of Ewelme and Swyncombe manors, and was administered by a succession of high-status keepers including the Knollys family of Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 104)

In 1627 the park was sold by Charles I, passing soon afterwards to Thomas Howard (d. 1669), earl of Berkshire, who built a new mansion house. The estate was then reckoned at 895 acres. In 1675 Thomas's son sold it to Robert and William Pinsent of Wiltshire, who converted the remaining parkland to tillage. (fn. 105) Two farms and farmhouses remained in the mid 19th century, when the estate belonged to Edward Hulton; (fn. 106) later owners included Thomas Taylor of Aston Rowant, who sold it in 1889, and Walter Heriot, who built the present Ewelme Park House in 1913. (fn. 107) The estate was sold in 1934 following Heriot's death, and later belonged to the Misses Keyser and to Lt-Col Walter d'Arcy Hall. In 1960 it was bought by Michael Colston, the owner in 2012. (fn. 108)

Ewelme Park House A lodge existed probably by the later Middle Ages, and was repaired by the Crown in the mid 16th century when it was occupied by the park's keepers or by other royal officials. In 1609 it was said to be in good repair. (fn. 109) Before 1649 the earl of Berkshire built a 'new brick house' worth £4,000, which in 1662 was assessed on 41 hearths, making it one of the largest houses in the county. (fn. 110) After the earl's death the Targe and magnificent house' quickly decayed, however, and by the early 18th century it was 'entirely pulled down and the surrounding land cultivated. (fn. 111)

The present house was built in 1913, probably on or near the site of its 16th- and 17th-century predecessor. Designed by the architect L. Stanley Crosbie (d. 1962) in a neo-Tudor style, the first floor of the central range is timber-framed, and flanked on its east and west sides by projecting wings creating an H-plan. Most of the walls are roughcast, and the sweeping roofs are slated. The wide north-facing entrance front is bounded by a spacious courtyard, while inside, an impressive full-height drawing room with a minstrel's gallery and barrelled ceiling is lit by an 18-light mulhoned-and-transomed window. (fn. 112) The house overlooks the valley which ran through the medieval park, sweeping down the Chilterns scarp towards Ewelme village.

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Farming has always dominated Swyncombe's economy, and in the 20th century remained the main source of employment within the parish. Sheep-and-corn husbandry was widespread as elsewhere in the area, while cattle-rearing and dairying were also significant, and expanded during the late 19th-century agricultural depression. By then around ten inclosed farms of varying size were scattered across the parish, most of them let to tenants, although landowners generally retained control of the parish's extensive woods. Woodland trades and crafts flourished from the Middle Ages, and in the 19th century, when wood-related crafts expanded considerably, several women were employed chairmaking, while a small brickmaking industry at Russell's Water operated from the 1740s to 1850s. In the 20th century the range of trades and crafts diminished and the parish became more purely agricultural, although by then the majority of inhabitants worked elsewhere in unrelated occupations.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 103)

From the Middle Ages the parish contained a mixed landscape of extensive chalk downland, open and inclosed arable fields, extensive woodland, and (from the 14th century) at least one deer park. In closure of the irregular open fields was a gradual process. As early as 1230 Bec abbey was inclosing the demesne with ditches and suppressing common rights there, (fn. 113) but open fields were still mentioned in 1596 and 1609, and common pasture rights persisted during fallow. By then large areas also lay in closes, however, and the landscape of later maps was spreading inexorably across the parish. (fn. 114) An exception were the downs in the parish's north-western corner, which in 1839 still covered 373 a., (fn. 115) and were used mostly for sheep-grazing. (fn. 116)

Field names such as stocking and breach suggest woodland clearance both before and after the Conquest. (fn. 117) No woodland was recorded in Domesday Book, but Bec abbey held some in the later Middle Ages, and in 1288–9 sold produce worth £2 65. 7d. (fn. 118) Probably the medieval woodland was coppiced as in the 16th century, when wood was cut every 7–9 years and then fenced to protect the regrowth. (fn. 119) The woods also provided pasture: in 1609 the lessee of Swyncombe wood had commons there for all manner of livestock, and another tenant for his sheep. (fn. 120) In the 18th century most of the woodland lay along Coates and Reading Lanes and in the parish's southern part near Bix and Nettlebed, (fn. 121) and in the 19th and 20th centuries it was extended by plantations, covering c.240 a. in 1839 and 280 a. by 1878. (fn. 122) The medieval Ewelme park stretched across the parish's southern part from the Ewelme boundary to Park Corner, but was entirely cleared for arable by the later 17th century. (fn. 123)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

In 1086 Bec abbey's manor included 10 a. of meadow and land for 2½ ploughteams. None were in use, but as the manor's value had risen from £2 in 1066 to £3, (fn. 124) probably it was used for grazing livestock (especially sheep) and as a source of wood. (fn. 125) The monks held a three-day fair on 16–18 June, most likely for selling sheep after shearing: the fair was confirmed by King John in 1203, on payment of 5 marks (£3 65. 8d.) for a palfrey. (fn. 126) In 1227 it was said to be damaging one held on the same days at Wallingford, and was prohibited; undeterred, the monks secured consent to hold a similar fair on 3–5 July, moved to 6–8 July in 1234. In 1288–9, when it was held before the gate of the manor house, it raised 75. in tolls. (fn. 127)

During the 13th century sheep-and-corn husbandry was widely practised, and woodland was carefully managed: in the 1240s tenants were fined at the manor court for damaging the abbeys corn, illegally grazing sheep in its pasture, and stealing its wood. (fn. 128) At least 26 tenants were named c.1248, each holding yardlands and crofts, (fn. 129) although the manor may have been reorganized before 1279, when ten serfs or servi each held ¼ yardland (8 a.) for standardized services, and eleven cottars held crofts. (fn. 130) Serfs were allowed common pasture for a horse, six oxen, six pigs, and fifty sheep, and were rewarded in kind for some labour services. (fn. 131) The latter were heavy, including ploughing, harvesting, sheep-shearing, and carting, while the abbey levied pannage for the right to pasture pigs. (fn. 132)

The abbeys demesne contained two carucates (c.256 a.), which in 1288–9 produced almost 88 qrs of wheat, 72 qrs of barley, 67½ qrs of oats, 49 qrs of mancorn (a mixture of rye and winter barley), and smaller quantities of dredge (spring barley and oats), peas, and vetches. (fn. 133) Most was consumed on the manor, sales of grain producing only £3 155. 7½d., less than 10 per cent of total receipts. Sales of wool and fleeces generated £6 2s. 5d., livestock £2 14s. 5d., and wood £2 6s. 7d., with smaller sums raised from the sale of milk, butter, honey, and hens. Tenants' rents, by contrast, contributed around half the manors income. The demesne was managed by a bailiff, who after deductions delivered £8 125. 3¼d. to the abbeys priory at Ogbourne (Wilts.). (fn. 134)

In the 1290s the monks leased the manor (excluding tenants' rents) to John Romayn of Chinnor for £10 a year, the demesne then including 300 a. of arable, 100 a. of inclosed pasture, 5 a. of meadow, 18 cattle, and 579 sheep. (fn. 135) A modest valuation of 3d. per acre of arable was characteristic of the area, although the meadow's scarcity raised its value to a more impressive 35. per acre. The demesne additionally included common pasture worth 45. 6d., wood valued at 135. 4d., and a dovecot. (fn. 136) By 1324 some land had fallen out of cultivation and its value had shrunk, while a countrywide decline in rural fairs was reflected at Swyncombe by the collection of a paltry 15. in tolls. The monks' withdrawal from demesne farming may, however, have provided opportunities for their tenants. The sum raised from villeins' rents increased and free tenants (paying rents totalling 51s. 10d.) were mentioned for the first time, while an increase in court fines perhaps reflected a more active land market. (fn. 137)

The Black Death apparently led to long-term population loss in Swyncombe, (fn. 138) and in the 15th century the trend towards livestock farming at the expense of arable continued. The manor's meagre land values in 143 5 – 100 a. of arable worth 2d. an acre and 300 a. of pasture worth 1 d. an acre – suggest that agricultural productivity remained at a low ebb, (fn. 139) while the creation or extension of the deer park similarly points to the availability of cheap land and a decline in arable farming. (fn. 140) Henry Adene (d. 1507), who bequeathed 500 sheep, may not have been typical, though his prosperity hints at the likely scale of Swyncombe's pastoral husbandry in the later Middle Ages. (fn. 141)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

From the 16th century Swyncombe's economy was based on sheep, cattle, corn, and wood, with sheep pastured on the downs, and livestock grazed also on the fallow and in the woods. Arable, pasture, and meadow lay mostly in closes, of which some were planted with woodland. (fn. 142) In 1534 Thomas Carter (d. 1551) paid £9 a year for a 40-year lease of the manor's demesne, herbage, and pannage, (fn. 143) and though the rent fell to £8 5s. under his son, Thomas was assessed on goods worth the substantial sum of £60 in 1546–7. His will suggests that he lived at Swyncombe in considerable comfort, presumably in the manor house. (fn. 144)

Among the parish's other farmers, John Barnade (d. c.1556) occupied Coates Farm, though his wealth at death (£14 14s. 8d.) was unexceptional.. (fn. 145) By contrast the yeoman William Mosden (d. 1575) left goods worth over £148, implying significant economic and social differences in the parish. (fn. 146) John Cooper (d. 1546) of Cookley Green combined farming with work as a miller and blacksmith, and made several bequests of sheep, but left goods worth only £7 3s. 4d. (fn. 147) His son Robert (d. 1596), who called himself yeoman, held arable in the common fields, reared cattle and sheep, and sublet two houses to his Cookley neighbours. (fn. 148)

Woodland was leased by the Crown and coppiced on a regular cycle. Timber was reserved, although the manors lessee was entitled to estover (wood for repairs). (fn. 149) In 1621 around 100 a. of Swyncombe wood was 'thin set' with 574 beech, 74 oak, and 106 ash, (fn. 150) while at Ewelme park the earl of Berkshire owned timber and wood worth £500, £60 more than the valuation placed on his 1,000 a. of arable, which were worth 75. or 105. per acre. (fn. 151) Some of his Ewelme park land was farmed by the prosperous yeoman Robert Carey (d. 1650), whose assets at his death (worth £140 125.) included 26 a. sown with oats and a further 13½ a. sown with wheat, barley, peas, and vetches. Careys ploughs, harrows, and dung carts were maintained using oak and ash poles, his pigs provided bacon, and his cattle provided dairy produce including cheese made in the buttery. Fuel included bavins cut from the woodland. (fn. 152)

Seventeenth-century farm sizes probably varied considerably. The labourer John Jemmett (d. 1639) and his son Robert (d. 1675) were smallholders, with only a few livestock and a plot of land quicksetted round'. (fn. 153) The husbandman Thomas Foster's lease was worth a modest £6, and at his death in 1630 he left wheat, barley, and peas worth only £5 10s., together with 44 sheep worth £14. John Wright (d. 1668), one of the Fettiplaces' tenants, may have occupied more land, but like Foster practised sheep-and-corn husbandry and kept few cows or pigs. (fn. 154) Cattle-rearing was more prominent on the Ewelme Park estate, where farms seem to have been larger and tenants richer. Carey was succeeded there by John Hall (d. 1650), while a second farm was occupied by William Pool (d. 1636) and his son Woolstone. In 1676 the latter's crops and livestock were worth the substantial sum of £190. (fn. 155)

By the 18th century large leasehold farms were also emerging on Swyncombe manor. The former demesne (c.700 a.) produced an annual rent of £240, and before 1736 was divided into two large farms occupied by Stephen Bacon and Thomas Hussey for £180 and £120 a year. Coates farm brought in £70 a year, and the smaller farms held by John Cottrell and John Lovegrove £10 and £4 8s. respectively. (fn. 156) Despite the increase in size, farming continued largely as earlier. Sheep and corn were the main source of Henry Boulters wealth in 1721, while John Hussey (d. 1728) additionally reared cattle and pigs. (fn. 157)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

In the early 19th century the parish contained at least ten farms. Three (Lower, Cookley, and Coates) were leased from Swyncombe manor, whose Home farm was managed by a bailiff. The Ewelme Park estate was leased as Ewelme Park and Parkcorner farms, while Little Parkcorner and Digberry farms were held from Thomas Toovey of Joyce Grove in Nettlebed, and New farm from the owner of Redpits (in Bix). Darkwood farm was owner-occupied, and other land was managed from Russell's Water. (fn. 158) Farm size varied greatly. In 1839 Lower farm (by then incorporating Coates) covered 812 a., some of it on Swyncombe Downs, while five others totalled 188–358 a., and three only 20–40 acres. (fn. 159) Some farms changed hands regularly when leases expired: at least eight tenants occupied Lower farm during the 19th century, although Ewelme Park farm remained in the hands of the Saunders family for several decades. (fn. 160)

Swyncombe's farmland was not naturally fertile, and in the early 19th century wheat was sown only every five or six years. Careful manuring was required to support the crop, a technique which Arthur Young observed with approval on Lower farm in the 1810s. Even so, in 1839 the tithe commissioner considered that most farms were slovenly tillaged'. (fn. 161) By 1851 an estimated 92 labourers were employed on eight farms covering c.2,200 a. in all, (fn. 162) and a similar acreage was reported in 1870 when around three fifths (1,340 a.) was arable, growing wheat, oats, barley, and fodder. The rest (830 a.) was either fallow or permanent pasture. Livestock totalled 2,384 sheep, 178 pigs, 75 horses, and 60 cattle, distributed among the eight chief farms and two smallholdings. (fn. 163)

Sheep-and-corn husbandry continued during the agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, though with a noticeable shift towards dairying: in 1910 less than half the cultivable area was arable, with larger quantities of oats and fodder crops sown in place of wheat and barley. Sheep numbers had fallen to c.1,500, while the cattle herd (including milking and breeding stock) stood at 172. The appearance of 30 a. of cherry orchards was characteristic of the area, (fn. 164) and woodland remained important. Prior's wood belonged to absentee landowners until 1902 when it was sold to Charles Ruck Keene, (fn. 165) and in 1921 timber on the Swyncombe estate was valued at the enormous sum of £31,910. (fn. 166)

Farms in the early 20th century were leased from the same large estates, but with some changes. On Swyncombe manor, Lower farm (322 a. in 1910) was reduced in size and eventually taken in hand, along with the existing Home farm (162 a.) and recently-created North farm (144 a.). (fn. 167) The estates other farms – Coates (217 a.), Cookley (114 a.), Darkwood (61 a.), and Stockings (100 a.) – remained tenanted. Ewelme Park farm (233 a.) was managed by its owner Walter Heriot, but Parkcorner farm (344 a.) was leased, and so too were the Joyce Grove estates small Digberry and Little Parkcorner farms (20–24 a.). Another 168 a. belonging to Redpits farm were in hand. (fn. 168)

In the 1920s–30s sheep, corn, and cattle remained dominant, (fn. 169) with some specialization. In 1942 the mostly arable Lower farm (313 a.) was 'well run' by its tenant Arthur Morris, while at Ewelme Park (627 a.) the foreman William Cook managed a substantial arable acreage and a pedigree herd of Jersey cattle. Pigs, poultry, and cattle were fattened on the owner-occupied Darkwood farm (48 a.), and at Little Parkcorner farm (32 a.) the owner Alfred Aley sold milk from a small dairy herd. A more traditional balance of sheep, corn, and cattle was maintained on the Christie-Millers' Home farm (209 a.) and on Cookley farm (120 a.), which suffered from lack of capital, while on Coates farm (311 a.) the land was particularly cold, requiring a long period laid down to grass in order to regenerate the soil. (fn. 170)

In the later 20th century the proportion of arable increased, reaching c.57 per cent by 1970. Barley production in particular expanded, accounting for over half the sown acreage in 1960, and around three fifths ten years later, although wheat was predominant by the 1980s. Oilseed rape was introduced as elsewhere, altering the colour of the landscape. (fn. 171) Farm size remained variable, with many farmers continuing to specialize: by 1970 the parish supported two dairy farms, two cereal farms, two pig or poultry farms, and another rearing cattle, together with one mixed and two part-time farms. A similar pattern persisted in the late 1980s, when ten farms employed a total of 37 workers. (fn. 172)

TRADES, CRAFTS, AND RETAILING

Crafts and trades were practised from the Middle Ages, many of them reliant on the parish's woodland. The occupational surnames Carpenter, Collier, Cooper, Forester, and Smith were recorded in the 13th and 14th centuries, (fn. 173) with Collier (meaning charcoal maker) persisting as a field name. (fn. 174) Small-scale brewing also continued throughout the Middle Ages. (fn. 175)

A horse-mill existed by the 1530s, owned by the lessee of Swyncombe manor (Anne Broke) and used perhaps for grinding malt. John Cooper later left the mill house and mill horse to his son Robert, who retained the tenancy in 1574. (fn. 176) Another horse-mill, making oatmeal, was owned by Eleanor Norcott (d. 1656), and several malt mills (probably hand-powered) were mentioned in the 17th century. (fn. 177) John Cooper also held a forge, (fn. 178) while the Norcott family included successive carpenters. (fn. 179)

Eighteenth-century craftsmen included the blacksmith Thomas Cottrell (d. 1768) and the carpenter Richard Pink (d. 1758), while Henry Newell (d. 1714), an edge tool maker, left a workshop and grindstone house to his son. (fn. 180) John Lloyd ran a public house in the 1750s–60s, and Robert West (d. 1784) of Park Corner was a shopkeeper, (fn. 181) while a brick kiln at Russell's Water was established from the 1740s. (fn. 182) Even so in 1801 only seven people (2.5 per cent of the population) were employed primarily in trade or craft, and in 1821 only 4 out of 64 families. (fn. 183) The smith Stephen Wixen had a forge at Park Corner, (fn. 184) and by 1841 there were five blacksmiths, three sawyers, two brickmakers, carpenters, and shoemakers, and a tailor, wheelwright, and woodman. Henry Earl was a publican at Park Corner, and Hannah Morris a grocer at Cookley Green. (fn. 185) Ten years later c.10 per cent of inhabitants were craftworkers, including eight women making chairs, two lacemakers, two needlewomen, two thatchers, and a hurdle-maker. (fn. 186)

The chair-making industry declined over the following decades, along with other woodland occupations such as sawyer. Brickmaking at Russell's Water also faded away, the brickmakers supplementing their income by working as agricultural labourers. The range of occupations mentioned in the 1860s–70s, including dressmaker, glazier, and plumber, diminished towards the end of the century as the population fell and became more dependent on farm work and domestic service. Grocers shops at Cookley Green and Russell's Water closed, although at Park Corner the blacksmith William Wixen also sold beer, and a slightly wider range of shops and trades continued in the Pishill part of Russell's Water. (fn. 187)

Before the Second World War Park Corner retained an off-licence at the forge, a sand and timber merchant's yard, and a builder's and decorator's. (fn. 188) Following the closure of the Cookley Green post office in 1967 little non-agricultural employment remained, however, the parish becoming increasingly populated by commuters, and dependent on nearby towns for its shops and services. (fn. 189)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

Most of Swyncombe's medieval inhabitants were unfree tenants of Bec abbey. In the 13th century a distinction was made between the abbey's serfs (or servi), with holdings measured in yardlands, and cottars, who held smallholdings called crofts. Both types of tenant were heavily burdened by cash rents and labour services, but the serfs probably had a stronger commitment to farming than the cottars, who must have depended for part of their income on wage labour or non-agricultural activities. The contrast is suggested by fines levied at the manor court. Hugh Pick and Roger Puke, both cottars, were each caught stealing the lord's wood, while John de Fonte and Henry de la Dene, both serfs, were fined for grazing their livestock in the lord's pasture. (fn. 190)

The manor may have been reorganized between c.1248 and 1279, when services were apparently standardized and individual exemptions removed. (fn. 191) The appearance of free tenants in the early 14th century points to further change, perhaps reflecting the leasing of former demesne lands or the granting of permission to clear and cultivate land in the woods. (fn. 192) Nevertheless tax returns do not suggest any great prosperity. Apart from the prior (who paid 75. yd.) only six inhabitants were wealthy enough to be taxed in 1306, paying an average of 9½d. each, and in 1334 Swyncombe's payment of 225. comprised under 2 per cent of the total raised from the hundred. (fn. 193) Manor court proceedings continued to be dominated by infringements of the abbey's rights and property, while a few cases reflected the sometimes violent disagreements which arose between tenants. With population high and land in short supply most holdings were inherited rather than bought and sold, and at least one tenant was fined for illegally seizing land belonging to another. Competition for resources was particularly pronounced in years of hardship, even the rector trespassing on the lord's land during the great famine of 1316. (fn. 194)

Bec abbey maintained a manor house near the church, where courts were presumably held and where visiting monks were accommodated in comfortable surroundings. In 1288–9 more than £29 was spent at the house, in addition to payments to the bailiff and steward: in all, more than three times the manorial profits delivered to the abbey's priory at Ogbourne (Wilts.). The house, garden, and dovecot lay within an enclosure or cloister (claustrum), and the household was equipped with brass pots and other utensils. Tenants services' included carrying the monks' clothes (pannos) and other items to their manors at Ogbourne and Ruislip (Middx). (fn. 195)

As elsewhere, pronounced late medieval population decline provided opportunities for inclosure, accumulation of holdings, and conversion of arable to sheep pasture. (fn. 196) Further change followed Bec abbey's forfeiture of the manor in 1404 and its transfer to the Chaucers of neighbouring Ewelme. (fn. 197) Thomas Chaucer witnessed a land grant at Swyncombe in 1408, perhaps at the manor house, (fn. 198) but as the family lived in Ewelme itself the Swyncombe house was presumably leased then or soon after. Chaucers greatest impact was almost certainly the creation of Ewelme park, which took large swathes of Swyncombe parish out of cultivation. (fn. 199)

1500–1800

The Crowns seizure of Swyncombe manor in 1501 probably had little direct effect, since the manor was generally leased until its sale in 1627. Its 16th-century lessees were frequently resident, however, amongst them Anne Broke (d. 1532), the widow of a royal serjeant-at-arms, who lived with her maids and servants presumably at the manor house near the church. In 1524 she paid £2 10s. tax, when many others paid only 4d. Though buried in Ewelme church she was godmother to Richard and John Mosden (who farmed probably at Redpits), and left a silver-gilt goblet to the duke of Suffolk's treasurer Thomas Carter (d. 1551), who became lessee after her death. (fn. 200) He too was the parish's wealthiest taxpayer, assessed on goods worth £60, and enjoyed many of the trappings of a country gentleman. (fn. 201) The Roman Catholic Fettiplaces (who leased and later bought the manor) were probably continuously resident during the 17th century, (fn. 202) their steward William Bastian (d. 1663) being buried in the parish. (fn. 203) Francis Fettiplace was taxed on 12 hearths in 1662, double the assessment of the parish's next largest house. The grandest residence by far, however, was the earl of Berkshire's short-lived mansion at Ewelme park (built before 1649), whose quite exceptional 41 hearths made it one of the largest in the county. (fn. 204)

The manor's free tenants and copyholders displayed a considerable range of wealth and status. The yeoman William Mosden (d. 1575) was one of the parish's wealthiest farmers, employing five servants, and was a generous benefactor on friendly terms with the wealthy Ralph Spyer of Huntercombe. (fn. 205) Thomas Dowberry (taxed on £5-worth of goods in 1546) and George Anderson (taxed on £3-worth in 1581) were probably of similar standing, and Anderson oversaw Mosden's will. (fn. 206) Less well-off were John Barnade of Coates, John Cooper, and John Leafe (who had interests at Finstock), (fn. 207) while the copyholder Thomas Wanbourne, who paid 4d. tax in 1524, occupied only a cottage and close for the lives of himself and his wife. (fn. 208) Similar disparities continued in the 17th century, when the wealthy John Hall (d. 1650) of Ewelme park left goods worth more than £311, mostly grain, livestock, and farming equipment; (fn. 209) a few other yeomen left goods worth over £100, although most inhabitants' were worth less than half that amount. Even so only three houses noted in 1662 had more than three hearths, suggesting that even better-off farmers occupied relatively modest dwellings. Robert Jemmett (d. 1675), assessed on two hearths, had a hall and buttery with chambers above, while John Wright (d. 1668), assessed on three, had an extra chamber above the milk house. (fn. 210) A few squatter cottages were built on the commons or in the woods, though by the 18th century the commons were inclosed and the houses presumably subject to rent. (fn. 211)

Local wills reveal the usual family, social, and trade networks both within and outside the parish. John Carpenter's executor in 1638 settled debts in Cookley Green, Great Haseley, Maidensgrove, and Watlington, while John Wright (d. 1668) owed money in Greenfield (in Watlington) and Chinnor. (fn. 212) Intermarriage was common: Prudence London (d. 1663) was related to the local Halls and Jemmetts, while Richard Norcott (d. 1676) was godfather to members of the Benwell and Wheeler families. (fn. 213) A few such families remained for several generations, among them the Halls, Husseys, and Norcotts, (fn. 214) while even some poorer families were of long standing. Robert London (d. 1609) left goods worth only £5, while his descendant John London (d. 1710), a labourer, was little better off. (fn. 215)

In 1738 the rector reported that his parishioners were mostly poor labourers and a few better-off farmers, while the resident lord Samuel Greenhill enjoyed an income of £400–500 a year. (fn. 216) Leading farmers included Thomas Rose (d. 1778) of Coates farm, whose stock and furniture were auctioned after his death, (fn. 217) while William Crook (d. 1756) left a 'considerable estate' at Park Corner, although he came originally from Watlington. (fn. 218) Turnover amongst the principal farmers was high, only Henry Benwell and Thomas Cottrell remaining in the early 19th century from those listed in 1785. (fn. 219) Poverty amongst the parish's lesser inhabitants led by the 1770s to exceptionally high poor-relief costs, (fn. 220) and fuelled occasional wood stealing and poaching. (fn. 221) Social life is poorly recorded, although alehouses may have provided a focus: John Hussey's cottage included a brewhouse and drink-house in 1728, and in the mid 18th century John Lloyd was a licensed victualler. (fn. 222)

Swyncombe House in 1896, as rebuilt for Revd Charles Ruck Keene c.1840.

Since 1800

Swyncombe retained resident gentry throughout the 19th century in the form of the Keenes and their successors at Swyncombe House. Out of c.22 contributors to the parish's land tax, Benjamin Keene (d. 1837) paid three fifths of the total for the manor's woods and farms, and was both an active magistrate and often resident. (fn. 223) His son Charles (d. 1880) consolidated the estate, buying up additional cottages and land, (fn. 224) and in 1851 occupied the rebuilt Swyncombe House with his wife, three children, and fourteen servants, including a butler, housekeeper, cook, laundress, lady's maids, and footmen, most of whom were recruited from outside the parish. (fn. 225) An ordained clergyman, he was not always on good terms with Swyncombe's Scottish rector, the 'proud and poor' Hon. Henry Napier (1826–72). (fn. 226) His grandson Charles Ruck Keene (d. 1919), a captain in the Royal Fusiliers, let the house to the retired shipping merchant Emil Reiss, German-born but then a naturalized British subject, who in 1901 lived there with his family and 21 servants. (fn. 227)

The parish's farms and rural industries attracted migrant workers, so that by 1851 only around half the inhabitants were parish-born. Most tenant farmers and many of those involved in the brick and chair-making industries were incomers, while the schoolmistress Catherine Williams had been born in Newfoundland. The population grew steadily until 1861, when numbers began to decline in common with most other rural parishes: over thirty years Swyncombe lost almost a third of its population, and by 1891 only 30 per cent of inhabitants were native to the parish, suggesting that migration had increased. (fn. 228) Poverty was probably the main driver, Charles Ruck Keene observing that many Swyncombe families were reliant on their children's earnings in order to support themselves. (fn. 229) In 1891 around two thirds of households were still partly or wholly dependent on agricultural labour, while other inhabitants worked in traditional rural crafts. (fn. 230) The agricultural year dictated the rhythms of daily life, the rector noting in 1866 the effect that the corn and hay harvests, village feasts, and the change of farm servants at Michaelmas had on church attendance. (fn. 231)

Despite the fluid population, the Ruck Keenes and a few other landowners adopted a traditional and paternalistic role within the community. A few cottages were owned by Walter Heriot of Ewelme Park and Mary Hallett of Redpits, but most of the housing stock was still rented from Charles Ruck Keene, (fn. 232) who in 1897 hosted an entertainment for parishioners to mark Queen Victorias jubilee. Emil Reiss similarly opened Swyncombe House to celebrate his daughters marriage. (fn. 233) Even so the working population displayed some independence. Nine candidates stood for the new parish council in 1894, among them a gardener and a labourer, and of the five men elected three were farmers, one a carpenter, and one the blacksmith-cum-beer-seller William Wixen. (fn. 234)

During the First World War Swyncombe House was requisitioned for use as a Red Cross hospital. (fn. 235) Of its later owners Charles Christie-Miller (who bought it in 1929) (fn. 236) served for 35 years as chairman of the parish council, whose business in the 1920s included deliberations regarding new council houses at Park Corner and Russell's Water. (fn. 237) By 1931, those had led to a small increase in the number of households. (fn. 238) A cricket club was established c.1920, playing near Cookley Green, while a social club continued until 1948 and a boy's football club until 1953. (fn. 239) A few non-farming newcomers settled before the Second World War, amongst them Swyncombe's local historian (and long-term churchwarden) John Bridge. (fn. 240) During the later 20th century the trend continued, with large numbers of retired people and commuters buying and often enlarging the parish's older houses, despite the relative lack of new house-building other than a few scattered groups of council houses. (fn. 241) Clubs and societies met mostly at the school, mission room, or village hall in Russell's Water (built in 1975), and in 1977 included a cricket club, youth club, Silver Threads club, village hall committee, and the Friends of Swyncombe school. (fn. 242) The parish council remained an important focus of community life in the early 21st century, overseeing the cricket pavilion and other amenities, and organizing a variety of social events. (fn. 243)

EDUCATION

Until the 18th century education received little attention from Swyncombe's absentee rectors. Thomas Toovey (rector 1723–56) claimed that the parish's poor labourers 'cannot afford their children time to go to school', and that few sent them to be catechized. (fn. 244) George Ruck (d. 1763), who acquired Swyncombe manor in 1758, paid for the teaching and clothing of c.10 children, (fn. 245) but in 1808 the rector William Woodroffe (1801–26) reported only modest private provision by himself and those parents 'capable of teaching'. The lack of anything more formal was attributed to the parish's widely dispersed settlement, which was 'most inconvenient... for collecting children together for instruction'. (fn. 246)

A Sunday school established by Woodroffe c.1817 taught c.30 children supported by subscriptions, (fn. 247) and in 1830 a Church of England day school on the north side of Cookley Green was opened using an educational charity established under Woodroffe's will. (fn. 248) Its long-serving master Robert Holland taught children from the age of five, but few remained after the age of ten, and attendance was reduced outside the slack winter farming season. (fn. 249) The Sunday school and a night school run by the rector occupied the same building. (fn. 250) A separate 'domestic training' or 'industrial' school (on the south side of Cookley Green) was opened in 1846 by Revd Charles Ruck Keene, (fn. 251) as an attempt to overcome the widespread practice of employing children in agriculture: pupils worked on Ruck Keene's Swyncombe estate during intervals in their teaching, the money earned providing a vital source of family income. (fn. 252) The school received a government grant, set at £33 in 1860 when it also received £48 in fees and donations, and in 1871 it taught 17 boys and 22 girls. (fn. 253) The rector had no involvement, despite the school having Anglican affiliations. (fn. 254)

In 1878 the school was rebuilt and reorganized as an Anglican primary school, replacing the old Church of England school which subsequently became an Anglican mission room. Proceeds from its sale endowed a charity to fund the education of poor children. (fn. 255) The new school had accommodation for 111, and an average attendance in 1889 of 82; (fn. 256) it was further enlarged in 1893–4, when income from grants and voluntary contributions exceeded £283. (fn. 257) Under the master James Hibbs it made good progress, but from 1894 it suffered from frequent changes of staff, (fn. 258) and though linked to the National Society in 1903 it was described the following year as in a 'very backward state'. (fn. 259)

Reports over the period 1909–33 were generally satisfactory, despite continuing problems of high staff turnover and large mixed classes. (fn. 260) In 1937 the school was reorganized for mixed junior and infant children, with seniors attending Rotherfield Central School, which caused numbers to fall from 57 to 20. (fn. 261) During the late 20th century the Friends of Swyncombe School raised funds for its upkeep, holding a fair on the green in 1974. (fn. 262) Numbers were sometimes increased by the children of Travellers camped at Christmas Common (in Watlington), but in 1984, with only three local children enrolled, the school was closed. (fn. 263) The educational charities established by William Woodroffe and from the sale of the old school continued (as the Swyncombe Educational Charity) until 2005, when the remaining funds were spent and the charity was wound up. (fn. 264) The charities had formerly yielded c.£15 a year in the early 20th century. (fn. 265)

A Sunday school continued in 1948 when the newly formed parochial church council assumed responsibility, and in 1955 had an average attendance of c.30. (fn. 266) Technical classes funded by the county council in 1895 were not repeated. (fn. 267)

CHARITIES AND POOR RELIEF

A few one-off bequests to the poor were made in the 16th and 17th centuries. Anne Broke (d. 1532) gave 2 bu. of malt to every household in Cookley Green, (fn. 268) while William Mosden (d. 1575) left £2 for the poor at his burial, and £20 to be distributed in sums of 205. a year. (fn. 269) John Carpenter (d. 1638) left a total of £7 115. for the poor, Bartholomew Fettiplace (d. 1686) £15, and the rector William Duke (d. 1696) £5, other bequests amounting to 205. or less. (fn. 270) The parish's sole endowed charity was established by the lord Francis Fettiplace (d. 1671), who left £10 to be lent out at interest, with the proceeds divided annually among the poor by the parish overseers. By 1738 all memory of its foundation was lost, although interest of 105. a year was still being distributed. In 1758 the money was borrowed by a labourer who was unable to repay it, and the charity ceased. (fn. 271) Offertory money collected in church was usually also given to the poor, (fn. 272) although the rector Thomas Toovey (1723–56) declined to make collections on the grounds that 'few care to be distinguished for their poverty'. Parishioners, he claimed, would either give when they can't afford it', or refuse to attend because 'they would not publicly proclaim their inability or poverty'. (fn. 273)

The sums raised from such initiatives were negligible, and from the 17th century the overseers and churchwardens collected parish poor rates on the usual pattern. (fn. 274) In 1776 annual spending on the poor totalled £215, the highest sum in Ewelme hundred, rising to £225 in 1783–5 (fn. 275) and £392 in 1803, when 43 people (including 17 children) received regular out-relief, and 47 occasional relief: in all, almost a third of the population. Costs rose less sharply to £446 in 1813, and fell to £378 in 1815, when c.13 per cent of the population received help: 25 people permanently, and 15 occasionally. (fn. 276) From 1816 post-war slump increased distress, raising expenditure to almost £600 in 1819 (c.35s. per head of population). From 1822, as agriculture recovered, it rarely exceeded £450 or 255. a head. (fn. 277)

In 1834 Swyncombe became part of the new Henley Poor Law Union, (fn. 278) and in 1845 two cottages formerly used to house the poor were sold to Charles Ruck Keene. (fn. 279) Inhabitants regularly entered the union workhouse, where c.40 died between 1837 and 1943. (fn. 280) The church continued to distribute alms, including old fencing from the churchyard, which in 1861 was given to the rector for the benefit of the poor and was presumably distributed as fuel. (fn. 281)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Swyncombe had its own church by the late 11th century, when it belonged to Bec abbey. The living (a rectory) was one of the poorest in the deanery, and few of its medieval incumbents were particularly distinguished. In the 14th century the advowson was confiscated by the Crown, and from the 16th century most rectors were presented by the Lord Chancellor on the Crowns behalf. The Reformation caused considerable disruption including a ten-year vacancy, and Catholicism persisted during the 17th century, encouraged by the resident Fettiplaces, who maintained a private chapel. Protestant Dissent remained minimal until the 19th century, when a Primitive Methodist chapel was established at Park Corner. The benefice remained independent until 1985, when it was merged first with Britwell Salome and later with a team ministry based at Watlington.

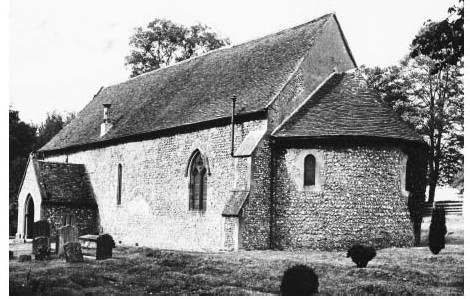

CHURCH ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

Swyncombe's late 11th-century church contains a font of similar date, and may have been fully independent from its foundation. (fn. 282) Its endowment was tiny, however, and the surviving small, plain building was perhaps originally intended only for the abbeys local servants and estate workers. (fn. 283) The dedication to St Botolph (d. 680), an East Anglian abbot, is unusual in Oxfordshire, and perhaps reflects East Anglian connections via the nearby Icknield Way. (fn. 284) Certainly the dedication must be medieval, since Bec abbeys 12th-century annual fair at Swyncombe was held at the time of St Botolph's feast (17 June). (fn. 285)

The parish belonged to Henley rural deanery until 1852, and later to those of Nettlebed (1852–74) and Aston (from 1874). Its ecclesiastical boundaries were expanded in 1973 by the addition of part of Pishill around Russell's Water and Maidensgrove, (fn. 286) and in 1985 the benefice was united with Britwell Salome, the ecclesiastical parish taking in parts of Watlington, Bix and Pishill, and a detached part of Ewelme. (fn. 287) In 1997 it was united with the combined benefice of Watlington, Pyrton and Shirburn to create the new benefice of Icknield. (fn. 288)

Advowson, Glebe, and Tithes

Bec abbey was patron in 1239, and presumably from the church's foundation. (fn. 289) The Crown confiscated the advowson during the wars with France, and between 1374 and 1400 the king presented every rector. (fn. 290) In the 15th century, however, the advowson passed with the manor from John, duke of Bedford, to Thomas Chaucer and his successors, (fn. 291) Sir Thomas Wentworth presenting for one turn only in 1526 or 1527 by grant of Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk. (fn. 292) In 1535 the Crown recovered the advowson with the manor, and remained a joint patron of the united benefice in 2009. In practice the patronage was usually exercised by the Lord Chancellor. (fn. 293)

The rectory was valued in 1254 at only 4 marks (£2 13s. 4d.) a year, one of the lowest assessments in Henley deanery. (fn. 294) Late 13th and early 14th-century valuations put it slightly higher at £4 13s. 4d., excluding a £2 pension to Bec abbey, (fn. 295) and a similar valuation was returned in 1428. In 1526 the benefice was still worth only £5 6s. 8d. gross, rising to £8 by 1535. (fn. 296) The glebe comprised only an acre on which the rectory house, garden, and outbuildings were laid out, (fn. 297) though by the early 19th century the tithes generally yielded over £300, and were commuted in 1839 for a rent charge of £415. (fn. 298) Even so during the agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th century the rector's net income rarely reached £250, rising to over £400 from the 1920s, but falling to £340 in the 1940s. (fn. 299) In 1956 the living was raised to £550 a year in an attempt to attract a new rector. (fn. 300)

Rectory House

In 1662 the rectory house was assessed on two hearths, suggesting a very modest residence which, like its successor, stood probably a little way north of the church and Swyncombe House. In 1685 it was 'in good repair', (fn. 301) but by c.1734 it was greatly decayed' and was repaired by Thomas Toovey (rector 1723–56), who lived there briefly (fn. 302) Thereafter it was often vacant, and by 1778 it was no longer fit for use. (fn. 303) Repairs were carried out during the 1780s–90s, but in 1802 it remained in a 'ruinous state'. (fn. 304)

A new red-brick and tiled house was built the following year by the Oxford architect Daniel Harris, incorporating a study, two parlours, a kitchen, and a thatched barn and new stable. (fn. 305) Henry Napier (rector 1826–72) nevertheless claimed that the house was dilapidated and the rooms 'very small and inconvenient', and in 1827 the architect Thomas Plowman considerably enlarged it, creating a 'picturesque asymmetrical' entrance front with a central porch and projecting pedimented bay. (fn. 306) Further major work was undertaken in 1951–2 when the rear was demolished, the remodelling incorporating plans drawn up by the architect Lionel Brett (d. 2004) in 1945. (fn. 307) Napier's drawing room, dining room, study, and kitchen were retained. (fn. 308) The house was sold following Swyncombe's incorporation into the Icknield benefice in 1997. (fn. 309)

PASTORAL CARE AND RELIGIOUS LIFE

The Middle Ages

Twenty-eight rectors of Swyncombe are known before the Reformation. The earliest, Laurence de Stoke (rector 1239–68), was typical of the parish's 13th- and early 14th-century clergy, both by being in minor orders at his presentation and by being university-educated. (fn. 310) Robert Nel (rector 1279–1305) was similarly described, while his successor John de Henney (1305–8) was an Oxford graduate. (fn. 311) William de Wanating (rector 1268–?79), a deacon at his presentation, came probably from Bec abbey's Berkshire manor of Wantage, while John Hende (rector 1357–?74) hailed from the Bec manor of Bledlow (Bucks.), and John de Stanford (rector 1308–19) and William de Stanford (instituted 1319) possibly both came from Stanford in the Vale, very close to Wantage. (fn. 312) In the 1330s Stanford was in the service of the prioress of Goring. (fn. 313) Of eleven rectors presented by the Crown between 1374 and 1400, none remained in post for more than a few years: most were priests from other dioceses who exchanged their living for that of Swyncombe, and John Forster (rector 1391–2), formerly of Glendon (Northants.), was an Oxford graduate. (fn. 314) John Carswell (rector 1410–?31) was presented by John, duke of Bedford. (fn. 315) Two medieval bells suggest either lordly patronage or initiatives by parishioners. One, bearing an inscription to Jesus, was forged in the early 14th century probably at a provincial foundry, while the other may be the work of the bellfounder John Barber (d. 1404) of Salisbury or a successor. (fn. 316)

Later 15th-century rectors included John Seynesbury (d. 1454), who also served Ewelme and was first master of the almshouse there. (fn. 317) As earlier, several incumbents were Oxford graduates, among them John Getour (1456–73), who was later appointed to Bix, and William Synger (1481–93), who held Swyncombe in plurality with Erdington (Warws.). (fn. 318) Long-serving incumbents included Peter Benson (rector 1493–c.1526), who on his retirement received an annual pension of £2 10s. (fn. 319) His successor Richard Moke witnessed the will of Anne Broke (d. 1532), lessee of the manor, who left a chalice, altar cloth, and vestments to the church, and property to fund a taper to burn before the sacrament during mass on Sundays and holy days; she also gave the rector a horse worth £1 for a mortuary, and £1 in cash for prayers for her soul. (fn. 320) A further hint of pre-Reformation practices survives from the late 16th and early 17th century, when mention was made of an unidentified building 16 ft by 12 ft at which offerings to St Botolph were formerly made. (fn. 321)

The Reformation to 1800

Anne Brake's gift did not survive the Reformation: in 1553 the parish's chalices and surplices were removed, although the two bells were left hanging in the porch. Her property given to support the taper was confiscated in 1574. (fn. 322) The rector Richard Moke may have supported reform (fn. 323) and resigned in 1556, when William Green was presented by Princess Elizabeth. His incumbency seems to have been extremely brief, and possibly he was forced out by Marian persecution. For a decade Swyncombe was left vacant until the appointment of Ambrose Lancaster (rector 1566–82), who also served as vicar of Watlington. (fn. 324) In the meantime the cure was presumably served by neighbouring clergy.

Lancaster subscribed to the Elizabethan Settlement, but the parish remained religiously divided. William Mosden (d. 1575), who left 205. to the church, was almost certainly a Protestant, but at least one gentleman recusant was resident in 1586. (fn. 325) Edmund Hitches (rector 1582–1601) was reported to be 'sufficient in learning, but scandalous in behaviour', a comment possibly on his morals, but perhaps also hinting that he did not fully conform to current Anglican practice. (fn. 326)

In the 17th century the parish became a minor centre of Roman Catholic worship. The widow Agnes Deane was heavily fined for recusancy in the 1620s, (fn. 327) but a more important influence was the encouragement of the Fettiplaces, lords of Swyncombe from 1607. (fn. 328) Three papists were reported in 1676 and four in 1679 and 1706, worshipping probably at the Fettiplaces's private chapel. (fn. 329) Nevertheless Francis Fettiplace (d. 1671) was buried in the chancel of the parish church. (fn. 330) Small-scale Protestant Nonconformity was also evident, with four Dissenters mentioned in 1676 and three in 1683. (fn. 331)

Religious diversity was probably encouraged by absenteeism. Richard Broughton (rector 1601–6) employed a curate, (fn. 332) and his successors Robert Barnes (1606–12) (fn. 333) and Daniel Jones (1612–59) apparently made little impression, the latter living in Ewelme where he was master of the grammar school. (fn. 334) Richard Shepherd, who witnessed local wills in 1634 and 1638, was probably his curate. (fn. 335) Nathaniel Lane (rector 1660–6) probably resided, (fn. 336) but Samuel Everard (1666–88) and William Duke (1688–96) both also lived in Ewelme, where they occasionally officiated and where Everard, too, was grammar master. (fn. 337) Of their curates David Roberts was particularly long-serving, witnessing local wills in 1674 and 1686, and living probably at the rectory house. He was buried in the parish in 1691, owed £4 105. in wages. (fn. 338) Everard nevertheless responded personally in 1682 to an enquiry by the bishop about an alleged case of sexual misconduct. (fn. 339) Parishioners continued to request burial in the churchyard, but few made bequests to the church and nothing is known about the state of the fabric or the provision of services. (fn. 340)

A similar pattern continued throughout the 18th century. Daniel Ayshford (rector 1696–1723) was a pluralist who employed curates, (fn. 341) while Thomas Toovey (1723–56) was vicar of Watlington, and resided only briefly at Swyncombe. (fn. 342) On Sundays he officiated personally, delivering a sermon at morning service, but on his own admission it was 'not often that we have any congregation on afternoons, especially in the winter', which Toovey put down to the church's isolation and to previous neglect. Week-day services were rare and the parish's children were seldom catechized, while holy communion was celebrated four times a year, attended by 40–50 communicants at Easter and 10–12 at other times. (fn. 343) Toovey claimed that Roman Catholicism and Protestant Nonconformity had all but vanished, (fn. 344) and soon after his appointment donated a surviving silver chalice. (fn. 345)

Philip Billingsley (rector 1756–71) lived at Newington where he was rector, and in 1759 employed an unlicensed curate living at Britwell Salome. (fn. 346) A later curate (also unlicensed) lived at Dorchester. Services remained unaltered, with irregular attendance. (fn. 347) Under Thomas Stevens (rector 1771–87) the curate abandoned any pretence of holding an afternoon service in winter, living a mile from the parish because the dilapidated rectory house was deemed uninhabitable. (fn. 348) Stevens' short-lived successor Joshua Kyte appointed a curate on his institution in 1788, (fn. 349) while John Marshall (1789– 1801) tried to justify his non-residence by observing that apart from the living's inconvenient location, 'the necessaries of life could not be procured nearer than Nettlebed or Henley'. Somewhat disingenuously he added that 'it has always been the policy in that parish to keep the rector at a distance'. (fn. 350)

Since 1800

During the 19th century standards gradually improved under several long-serving resident rectors. William Woodroffe (rector 1801–26) struggled to overcome parishioners' habitual non-attendance, reporting in 1808 that age, infirmity, and distance kept many from the church. By 1817 most inhabitants attended on Sunday mornings, but few returned in the afternoon, and the average number of communicants had risen from 6–8 to only 10–12. (fn. 351) Further improvement was reported in 1820, when Woodroffe's 'ill health and declining years' forced him to employ a curate living at Ewelme. (fn. 352)

The Hon. Henry Napier (rector 1826–72) attracted larger congregations, holding a Sunday service on winter afternoons in the schoolroom at Cookley Green, and introducing a monthly communion. (fn. 353) Attendance was chiefly affected by the cycle of the farming year. (fn. 354) The bishop judged Napier'painstaking, earnest, [and] zealous', though 'full of prejudice against everything new', (fn. 355) and though he undertook two restorations of the parish church he refused to enlarge it. (fn. 356) A silver chalice and paten were donated during his incumbency, joining an almsdish given by Woodroffe in 1817, and Napier also produced a major historical study of Swyncombe and Ewelme parishes. (fn. 357)

Despite this resurgence Protestant Nonconformity gained new followers from the early 19th century. Woodroffe reported 'many enthusiasts' in 1808 and a 'few Methodists' in 1820, though no meeting house or resident preacher. (fn. 358) A Wesleyan Methodist chapel was built at Russell's Water (within Pishill parish) in 1836, (fn. 359) and in 1851 a small Primitive Methodist chapel opened at Park Corner. (fn. 360) Dismissed by Napier as 'ranters', the Primitive Methodists initially aroused 'warm opposition, but later received considerable support from local farmers and labourers. (fn. 361) Both chapels subsequently belonged to the Thame and Watlington Methodist circuit, the Park Corner chapel continuing until 1958. (fn. 362)

The pattern of worship established by Napier (two Sunday services and a monthly communion) continued under Rowland Smith (rector 1872–91). (fn. 363) His successor Charles Irwin (rector 1892–1948), in an attempt to overcome the long-standing problem of the church's remoteness, opened a mission room at Cookley Green, besides increasing the number of services and restoring the church roof. (fn. 364) Influenced by the Oxford Movement, he established an enduring High Church tradition which seems to have proved popular with parishioners. One of the Dixon family donated a silver paten in 1899, and following Irwin's death after 56 years in the parish a memorial tablet was erected at the parishioners' cost. (fn. 365)

In replacing Irwin the PCC proposed that Swyncombe's priest-in-charge Kenneth Jenkins should hold the benefice in plurality with his existing living of Ewelme, although the bishop preferred a union with Pishill. In the event neither scheme was approved, and after some delay Percy Underhill was appointed rector (1952–5). (fn. 366) His successors were Basil Andrewes (1956– 62) and John Riccardi Saint-Nicholas (1962–80), who was credited with reviving the parish's spiritual life and shared in its community activities. (fn. 367)