Pages 342-367

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

NUFFIELD

Nuffield lies in the Chiltern hills c.6.5km south-east of Wallingford and 11 km north-west of Henley-on-Thames. (fn. 1) The village, on the common's south side next to the church, is largely a 20th-century development: settlement before then was more scattered, comprising isolated farms and roadside cottages of which several, including the Crown Inn, lay along the main Oxford–Henley road. The economy was almost wholly agricultural until recent times, supporting at least six large farms in the mid 19th century, although the population comprised only 46 families in 1851 and even fewer by 1900. Subsequent residential development increased the number of households to 162 in 2001. (fn. 2)

The parish is widely associated with the motor-car manufacturer and philanthropist William Morris (1877–1963), Viscount Nuffield, who from 1933 lived at Nuffield Place. The house itself was built in 1914 by Lutyens's pupil Oswald Milne, who also designed the neighbouring Huntercombe Place. A Second World War internment camp near the latter became a borstal and, in a much expanded form, remained a prison in 2015. Other institutional buildings included an architect-designed clubhouse for the socially exclusive Huntercombe golf course, established on Nuffield Common in 1901, while Huntercombe Place later became a nursing home. (fn. 3)

PARISH BOUNDARIES

In the late 19th century Nuffield's long thin parish covered 2,104 acres. (fn. 4) The southern boundary with Newnham Murren followed that of the hundred, rising south-eastwards up the Chiltern scarp to the church, then descending the gentler dip slope towards Highmoor (in Rotherfield Greys parish). The western boundary with Benson contained a large indentation excluding former pasture at Harcourt Hill, (fn. 5) while the short northern boundary with Ewelme followed a track to Ewelme park in Swyncombe, possibly preserving part of the former Roman road from Dorchester to Henley. (fn. 6) The northern boundary with Swyncombe, adjoining Ewelme park, was marked partly by tree stumps, a characteristic feature of former medieval parkland. The irregular eastern boundary with Nettlebed followed roads, tracks, and woodland divisions, and that with Rotherfield Greys a dry valley called Stony Bottom. (fn. 7)

Some of those boundaries almost certainly derived from those of estates created before 1086, including a small estate at Gangsdown in the parish's western part. Huntercombe (in the east of the parish) remained part of the Benson royal estate until the 12th century, however, and though Nuffield church probably existed by then, its ecclesiastical parish seems to have remained fluid until at least the 1180s. (fn. 8) A path near Hayden Farm was associated with rogation-tide perambulations in the 1520s, (fn. 9) while the boundary at Harcourt Hill was disputed in the 1590s. (fn. 10)

In 1932 the parish gained 34 a. from Benson at Harcourt Hill, while larger changes in the 1990s took in land from Stoke Row and Crowmarsh in the south, and from Benson in the west, transferring Harcourt Hill and the former Warren farm to Ewelme. In 2011 the modified parish covered 3,190 a. (1,291 ha.). (fn. 11)

LANDSCAPE

Nuffield is a typical Chiltern parish of dissected hills and dry valleys, lying mostly on chalk, but with a mantle of clay-with- flints extending westwards from the Nettlebed and Rotherfield boundaries to Nuffield Common and Huntercombe Place. The common's sandy soils are particularly dry and porous, well suited for its current use as a golf course. The church sits nearby atop a small patch of older clay, at 212 m. the highest point in the parish. Chalk valleys separate it from Harcourt Hill (186 m.) and Warren Hill (172 m.) in the west, the ground falling to 110 m. near Mogpits on the border with Benson. From Gangsdown Hill (203 m.) and the Huntercombe plateau the ground shelves south-eastwards to 170 m. at Howberrywood and 122 m. at Stony Bottom. (fn. 12)

Flints were used in local buildings and for mending roads, while chalk was dug from small pits for spreading over fields. (fn. 13) Wells and ponds remained the only water source until a mains supply became available in the 1920s: in 1898 the ponds were cleaned out by the parish council, but inadequate storage meant that in times of drought some farmers still had to cart water from Ewelme. (fn. 14) Woodland was most extensive on the clay soils in the east, and a deer park was maintained at Huntercombe in the Middle Ages. By the 18th century much of the woodland had been cleared for farming, however, and only a relatively small area remained around Huntercombe End. (fn. 15) Later plantations of beech, oak, and whitebeam lent the landscape a verdure that was admired in the 19th and 20th centuries, and also provided for hunting. (fn. 16) A windmill stood on the common or heath from the Middle Ages, but had long disappeared by the golf course's creation. (fn. 17)

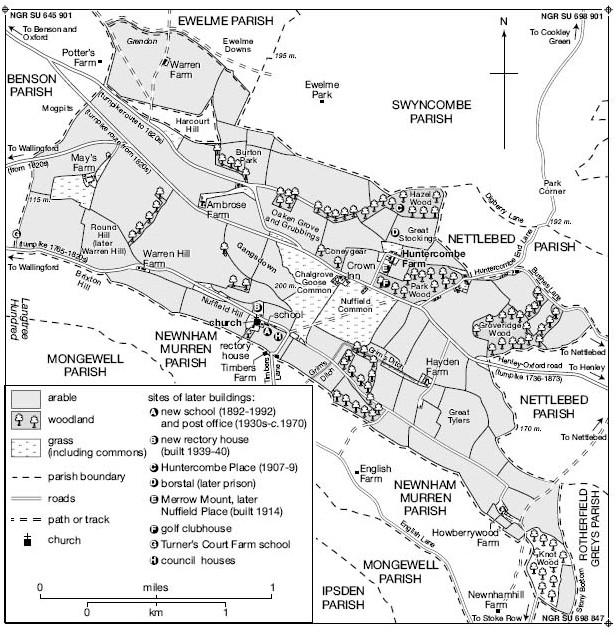

Nuffield parish in 1838, showing boundaries, land-use, and some later buildings.

COMMUNICATIONS

The main road through the parish from the Middle Ages was that from Henley to Oxford (turnpiked in 1736), which descended Gangsdown Hill to leave the parish near Potter's Farm (in Benson). In the 1820s the turnpike was partly diverted along a straighter road further south, passing Ambrose Farm and joining the old road near Gould's Grove. North of May's Farm it met a new improved turnpike road to Wallingford. The route was disturnpiked in 1873, and in the early 21st century formed part of the A4130 from Wallingford to Henley; the old course below Harcourt Hill survived as part of a long-distance recreational byway. (fn. 18) A parallel route to Wallingford passed the parish church and descended Nuffield Hill, leaving the parish at Turner's Court. In 1765 it was turnpiked to connect the Henley–Oxford road with the Wallingford–Wantage turnpike, but its use diminished following the changes of the 1820s. (fn. 19)

The road crossing Nuffield Common connects southwards along Timbers Lane with Ipsden Heath and Stoke Row, and northwards (along Huntercombe End Lane) with Park Corner and Cookley Green, in Swyncombe parish. Possibly that route formed part of a prehistoric ridgeway along the crest of the Chiltern hills, running parallel to the Icknield Way. (fn. 20) A road from Huntercombe End via Hayden Farm to English Farm (in Newnham Murren) was clearly marked on 18th-century maps, but in the 1750s was blocked for some years by a farmer, and was later reduced to a bridleway. Access from the main roads to other isolated farms was by paths and tracks, of which most survived in the early 21st century. (fn. 21)

No local carriers are recorded, inhabitants presumably using those which passed along the Henley–Oxford road. Bus services began in the 1920s and continued in 2011, when hourly buses to Henley and Wallingford stopped at the Crown public house. (fn. 22) Post was delivered in the 19th century from Nettlebed, and later from Henley; a letter box was located near the Crown from the 1870s, and in the 1910s another was provided at the school. The nearest post offices were at Nettlebed and Wallingford until the 1930s, when a sub-post office was opened in Nuffield's former school building. It closed c.1970. (fn. 23)

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

Prehistoric to Anglo-Saxon Settlement

A few scattered finds of Neolithic artefacts and prehistoric pottery suggest occasional occupation. (fn. 24) The most notable archaeological feature, however, is the Iron-Age Grim's Ditch, a probable tribal boundary which includes a small southwards projection where it crosses the Chiltern ridgeway, before entering the parish to the east of Timbers Farm and continuing south-eastwards to Hayden Farm. Openings at the corner of the projecttion suggest that it controlled movement, possibly of transhumant livestock between the Chilterns and the Thames. (fn. 25) Evidence of Roman activity is largely absent, save for an early 2nd-century Roman coin found near Harcourt Hill close to the Dorchester–Henley road, and a nearby coin hoard in Swyncombe. (fn. 26)

Anglo-Saxon activity (though not necessarily settlement) is indicated by the names of the parish's principal settlements. Nuffield (originally Tuffield) means tough open pasture, characteristic of the poor-quality grazing on the Chiltern ridge. The names Huntercombe (huntsmen's valley) and Gangsdown (Gangwulf 's valley) are equally typical of the Chilterns, the elements cumb (bowl-shaped valley) and denu (long valley) both being found throughout the region. (fn. 27) The form and extent of Anglo-Saxon settlement remains uncertain, but probably comprised scattered farms, perhaps (as later) with separate foci on a common or green. Possibly the parish was colonized from estate centres at Benson and Chalgrove: Huntercombe remained a 'hamlet' of Benson in 1279, while Gangsdown was associated with Chalgrove manor from the 1060s. (fn. 28)

Population from 1086

By 1086 Gangsdown supported four bordars and three servi, while Huntercombe's population was probably recorded under Benson. (fn. 29) In 1279 c.17 tenant households were mentioned at Gangsdown, and a further 21 on Huntercombe manor, (fn. 30) despite only five people paying tax there in 1306. (fn. 31) Huntercombe remained the slightly larger settlement after the Black Death, with 20 inhabitants paying poll tax there in 1377, and 17 (probably reflecting evasion) in 1381. Comparable numbers for Gangsdown were 11 and 7. (fn. 32)

In 1524 a total of 26 taxpayers lived at Huntercombe, Gangsdown, Swyncombe, and Cookley Green, (fn. 33) and 11 tenants held land in Huntercombe in 1537–8. (fn. 34) Only two taxpayers were named in the 1540s and four in 1581, (fn. 35) although by then population had begun to rise, with baptisms usually outnumbering burials. (fn. 36) In 1665, although the hearth tax listed only 9 houses in the parish, Huntercombe manor alone contained at least 15, (fn. 37) and 52 adults were mentioned in 1676. (fn. 38) Twenty houses were reported in 1738 and 23 in 1774, (fn. 39) and by 1801 there were 29 houses and a population of 139, rising to 198 people (in 39 houses) by 1821. The 19th-century population peaked in 1861 when 259 people occupied 41 houses, falling to 203 (in 40 houses) by 1901, partly because of agricultural depression. (fn. 40)

The 20th-century population was inflated by institutional residents at Turner's Court Farm School on the Nuffield–Benson boundary (opened in 1912), and at the Huntercombe borstal and prison (opened 1946). Total population rose from 215 in 1921 to 384 in 1931, of whom only 250 people were private residents. Their number remained little changed in 1951, but reached 402 ten years later following house-building in Nuffield village. Total population over the same period rose from 587 in 77 houses to 633 in 119 houses, peaking in 1971 at 656 people in 140 houses. Of those, 180 were male inmates of the farm school and borstal. Thereafter the private population changed relatively little until 2001–11, when numbers rose from 412 in 162 houses to 552 in 207 houses. The prison population increased from 242 to 387 over the same period. (fn. 41)

Medieval and Later Settlement

As elsewhere on the Chilterns medieval settlement was dispersed, and its precise form is impossible to reconstruct. At Huntercombe End on the border with Nettlebed, the 21 houses mentioned in 1279 probably clustered partly around a small green, while the contemporary manor house almost certainly occupied the site of Huntercombe Farm. The 17 households on Gangsdown manor may likewise have been scattered in small groups around the extensive Nuffield Common, especially on its north side near the road, (fn. 42) where inhabitants of Chalgrove (to which manor Gangsdown belonged) enjoyed long-standing grazing rights. (fn. 43) Other houses stood perhaps near the 12th-century church on the common's south-western edge, (fn. 44) and some isolated farms were also of medieval origin. William de la Hyde perhaps occupied Hayden farm, while Ralph de la Mare probably gave his name to May's (formerly Mare's) farm, both of which existed by the 15th century. (fn. 45) In the west of the parish, settlement at Grendon (around the later Warren Farm) extended into Ewelme and Benson in the 13th and early 14th centuries, but was apparently abandoned by the 1440s. (fn. 46) Settlement elsewhere may have also shifted focus, although suggestions that the 'villages' of Gangsdown and Huntercombe were deserted or severely shrunken during the later Middle Ages (fn. 47) are unfounded.

The broad settlement pattern appears to have changed little by the 19th century, when half of the 46 households recorded in 1851 were located at Huntercombe End and Gangsdown Hill, with the other half scattered across the parish in isolated farms, around the church, and in roadside cottages, including several at Port Hill in the east and Brixton Hill in the west. (fn. 48) Before the First World War two substantial villas – Huntercombe Place and Merrow Mount (later Nuffield Place) – were built to the north and south of the late 17th-century Huntercombe Farm, and a few other middle-class houses were added at Huntercombe during the 1930s, followed after the Second World War by a small housing estate north of the recently opened borstal. (fn. 49) The other main focus of early to mid 20th-century expansion was east of the church, which included some council housing. Together those areas accounted for the bulk of the increase from 46 houses in 1921 to 60 in 1931, 77 in 1951, and 119 by 1961. (fn. 50)

The prison and farm school created notable concentrations of population, and after the farm school closed in 1991 it was replaced by upmarket housing. Nevertheless settlement outside the village remained largely dispersed in the early 21st century, with small groups of houses scattered along roads and tracks. Clusters from west to east included those at May's Farm, Brixton Hill, Warren, Nuffield, and Harcourt Hills, Hayden Farm, Huntercombe End, and Port Hill. (fn. 51)

Looking south-west from Huntercombe prison (foreground) across the Oxford–Henley road, with Nuffield common and village at top left. Nuffield Place is left of the prison near the trees.

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Until the 20th century brick, flint, and timber were the most widely available and commonly used building materials, and were variously employed in farmhouses, cottages, and outbuildings. A survey of Huntercombe manor in 1766 suggests that the most substantial houses were brick-built and tiled, among them Huntercombe Farm. Its 18th-century red-brick front survives, together with its hipped slated roof, while its other walls are mostly flint. Other houses mentioned in 1766 were brick-panelled (i.e. timber-framed with brick infill), either tiled or thatched, and in various states of repair. Several cottages in particular were described as mean, ruinous, and tumbling down. (fn. 52)

Like Huntercombe Farm the parish's other surviving farmhouses suggest considerable prosperity, but display little in the way of grandeur or pretension. At Howberrywood the 17th-century farmhouse is of knapped flint with red brick dressings and a tiled roof, and on the Henley–Oxford road the Crown public house (originally timber-framed but now encased in brick and flint) is of similar style and date (Fig. 99). Timber-framing was used also at the 16th-century Hayden Farm, where the irregular close studding is infilled with brick and two panels are rendered. Barns at Howberrywood and Huntercombe Farms, set on flint bases with red brick dressings, are timber-framed and weather-boarded, while granaries of similar materials are supported on staddle stones. (fn. 53) May's Farm (burned down in 1902 and rebuilt on a different plan) appears on a map of 1635, depicted with a gabled front. That too was brick-built and tiled, with barns and other outbuildings of brick, timber, and thatch. (fn. 54) Probate inventtories and the hearth tax suggest that the broad run of the parish's 17th-century houses were relatively small and simply furnished, often with only a hall and buttery and chambers above. (fn. 55)

In the early 20th century three large houses were designed by Edwin Lutyens's pupil Oswald Milne. His first commission was Huntercombe Place, designed for the merchant banker William Brooks Close in Artsand-Crafts style in 1907–9. Of two storeys with attics, the house is of red brick with half-timbered gables, brick mullioned windows, and a complex tiled roof with elaborate brick stacks. A red-brick forecourt wall separated the reception rooms (to the west) from the service wing, which included a three-storeyed water tower, while the angled porch with four-centred arch opened into an oak-panelled hall, with decorative plasterwork by the Bromsgrove Guild. (fn. 56) Soon afterwards Milne designed the clubhouse for Huntercombe golf club (Fig. 100), its two projecting gabled wings flanking a long first-floor balcony across the central bays, whose steeply-pitched roof is surmounted by a small bell-turret. William Morris added a wing on the west when he bought the club in 1925. (fn. 57) Milne's final work in the parish was Merrow Mount, which later became Nuffield Place (described below). (fn. 58)

Other 20th-century buildings were more nondescript, and by the 1960s the village's council houses were in poor repair, with crumbling brickwork, shrunken woodwork, and inadequate insulation. Improvements were finally made in 1980. (fn. 59) A new single-storeyed and timber-built golf clubhouse was opened nearer the village in 1964, with large windows, a tiled roof, and a central clock turret, (fn. 60) while at the prison (opened near Huntercombe Place in 1946) most of the wartime internment buildings were replaced in the later 20th century by accommodation and administrative blocks in stark functionalist style. (fn. 61) Buildings at Turner's Court Farm School (lying mostly just over the boundary in Benson parish) included three-storey accommodation blocks, workshops, and offices (Fig. 15), but were mostly replaced by upmarket housing in the 1990s. (fn. 62)

MANORS AND ESTATES

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Nuffield belonged to Benson's royal estate. (fn. 63) A small estate at Gangsdown, separated before 1066, was absorbed after the Norman Conquest into Chalgrove manor, with which it passed in the late 15th century to Magdalen College, Oxford. A separate manor at Huntercombe was created probably in the 12th century, and passed in 1330 to Dorchester abbey, returning to lay ownership at the Dissolution. The two manors were combined in 1900, and were later bequeathed by William Morris (Viscount Nuffield) to Nuffield College, Oxford. Medieval lords of Gangsdown were mostly non-resident, but Huntercombe had a manor house (on the site of present-day Huntercombe Farm) from the 13th century to the late 17th, and from 1933 Morris lived at the modern Nuffield Place. Long-standing freeholds meant that manorial lands covered less than a third of the parish in the 1890s, (fn. 64) and landownership over all remained fragmented. (fn. 65)

GANGSDOWN MANOR

In 1066 a hide at Gangsdown was held freely (with Berrick Salome) by Ordgar, who after the Norman Conquest held it under the Norman baron Miles Crispin. (fn. 66) Miles's estates (which formed the core of the later honor of Wallingford) included Chalgrove, of which Gangsdown became a member, passing c.1190 to Hugh de Malaunay, and in 1231 to Drew Barentin, John de Plessis, and William de Huntercombe. (fn. 67) In 1233 it formed part of the partition of Chalgrove between the Barentin and Plessis families, and followed the descent of their Chalgrove manors: by 1279 it was held jointly by William Barentin and Margaret de Plessis, (fn. 68) and in 1290–1 a legal challenge by Hugh de Malaunay's heir Robert was defeated. (fn. 69) In 1485–7 it formed part of the Chalgrove estate acquired by Magdalen College, Oxford, which in 1564–8 added the parts held by George Pudsey and Lincoln College, Oxford. (fn. 70) Magdalen's combined Gangsdown estate became focused on Hayden farm (200 a. in 1838), (fn. 71) but in 1900 was absorbed into Huntercombe manor by the Chiltern Estates Company (below). (fn. 72)

HUNTERCOMBE MANOR

Huntercombe manor was probably separated from Benson by the Crown in the 12th century, and given to William Percehay, whose daughter married Eustace de Huntercombe. Their son William de Huntercombe (d. 1240) held a hide and half a yardland there, the overlordship of which was given by the king to the bishop of Carlisle. (fn. 73) William was succeeded by his son William (d. 1271) and grandson Walter (d. 1313), whose heir – his nephew Nicholas – sold most of the manor to Dorchester abbey in 1330. (fn. 74) The abbey held it until the Dissolution, and in 1545 it was sold by the Crown (with Soundess in Nettlebed) to Richard Taverner. (fn. 75)

In 1550 Taverner sold the manor to its former lessee Thomas Spyer (d. 1572), who was succeeded by his son Ralph (d. 1589) and grandson Thomas (d. 1591). (fn. 76) Thomas's son Ralph (d. 1623) was a minor, whose wardship and marriage were granted to his mother's second husband George Carleton of Brightwell Baldwin. (fn. 77) Ralph's son John Spyer (d. 1674) was succeeded by four daughters, among whom the manor (then c.740 a.) was divided. (fn. 78) The youngest daughter Elizabeth married (as her second husband) William Gibbons (d. 1728), whose daughter Mary married Richard Jones (d. 1742) of Ramsbury (Wilts.). Their interest passed to Richard's brother William Jones (d. 1753), whose daughter Elizabeth married William Langham (d. 1791) of Raunds (Northants.). He took his wife's surname, and later became a baronet. (fn. 79)

Elizabeth Jones died in 1800 possessed of the whole manor, which was divided between her nieces Frances and Elizabeth Burdett. (fn. 80) Elizabeth married Sir James Langham (d. 1833) of Cottesbrooke (Northants.), 10th baronet, whose son Sir James Hay Langham (d. 1893) inherited the reunited estate. His heir was his nephew Sir Herbert Hay Langham, 12th baronet, (fn. 81) who in 1894 sold it to H.H. Gardiner, purchaser of Nettlebed manor. Gardiner transferred Huntercombe in 1900 to the Chiltern Estates Company (of which he was a director), but in 1903 the estate was mortgaged to the Norwich Union insurance company, which foreclosed in 1907 and in 1925 sold the manor to William Morris (d. 1963), later Viscount Nuffield. He added Nuffield Place, and on his death left both house and land to Nuffield College, Oxford. (fn. 82) The college sold most of the estate in 1979, when it was managed from Timbers Farm in Newnham Murren. (fn. 83)

Manor House

No evidence has been found of a Norman castle at Huntercombe supposedly destroyed in the 12th century. (fn. 84) Nevertheless a manor house occupied by the Huntercombe family existed by the late 13th century, probably on the site of Huntercombe Farm, and in 1313 included a hall, chambers, chapel, kitchen, outbuildings, and garden. (fn. 85) A deer park lay adjacent. (fn. 86) The house may have been maintained by Dorchester abbey for its bailiffs and lessees, and was presumably taken over and probably rebuilt by the Spyers family in the 16th or 17th century. (fn. 87)

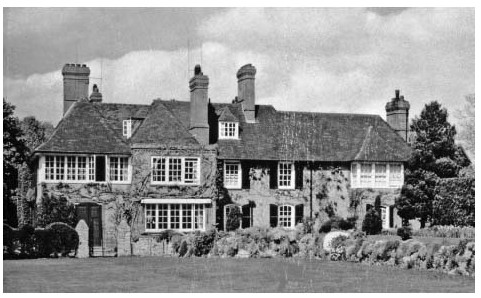

Nuffield Place (formerly Merrow Mount) from the south in 1960.

In 1665 the house (taxed on 10 hearths) (fn. 88) included a three-storeyed main range of three bays with a central porch, brick stacks, and a tiled roof, flanked by gabled and possibly projecting cross-wings (Plate 5). Outbuildings enclosed within strong courtyard walls may have included a barn, stable, and granary, and a gaol was added c.1650. (fn. 89) The Spyers' successors were non-resident, and in the late 17th or early 18th century the house was replaced by the present Huntercombe Farm. (fn. 90)

Nuffield Place

Nuffield Place, built in 1914 for the shipping magnate Sir John Bowring Wimble, was designed by Edwin Lutyens's pupil Oswald Milne (1881–1968), and originnally comprised a small L-shaped country house called Merrow Mount. (fn. 91) Influenced by Norman Shaw (d. 1912) as well as Lutyens, Milne included tall, narrow oriel windows, and used light-blue bricks with a soft bloom to contrast with the bright red quoins and other dressings. William Morris bought the house in 1933 and extended and modernized it: the ground-and first-floor verandas were walled in and roofed, and new rooms were added to the eastern side, producing a substantial and irregular building with sweeping tiled roofs, tall brick stacks, and several dormers above the two main storeys. The formal seven-bay west front, complete with sundial, remains the most impressive, though Morris's changes unbalanced Milne's original symmetry. Less imposing are the long and irregular garden-facing south front and the narrower north-facing entrance. (fn. 92) Nuffield College made a few structural alterations after receiving the house in 1963, but left its contents and furnishings untouched, allowing occasional public access through volunteers. In 2011 it gave the house to the National Trust, which opened it to the public the following year having embarked on a £600,000 fundraising programme. (fn. 93)

OTHER ESTATES

Medieval Freeholds

The site of Nuffield church (close to the southern boundary) may have belonged in the 12th century to the Bolbecs of Crowmarsh Gifford, (fn. 94) and throughout the Middle Ages the parish contained numerous freeholds of which some became absorbed into the two main manors. In the early 13th century William son of Geoffrey held 11/2 yardlands at Gangsdown, which his successor Alexander, a Wallingford vintner, defended against claims by Drew Barentin and John de Plessis. (fn. 95) Land at Gangsdown belonging to Robert of Ewelme was bought by John Carbonel in 1281, and may have been acquired by Thomas Barentin in the 1340s, (fn. 96) while in 1342 Philip de Englefield sold land at Gangsdown to Edmund de Bereford (d. 1354), which also passed later to the Barentins. (fn. 97) John James (d. 1396) of Wallingford built up a separate estate from the 1350s, for which he obtained free warren in 1394; (fn. 98) the estate included land in the west of the parish at May's Farm, and descended to James's great-grandson Edmund Rede (d. 1489) of Boarstall (Bucks.). (fn. 99) The Waces' and Chaucers' Ewelme and Swyncombe manors also included appurtenances in Nuffield, (fn. 100) and in 1440 the Chaucers' successor William de la Pole bought land at Grendon on the western boundary from the hospital of St John the Baptist in Wallingford. (fn. 101) Some woodland remained attached to the Crown's Benson manor in the 1430s. (fn. 102)

Other ecclesiastical landowners included Dorchester abbey, which acquired land in Huntercombe from Elias de Pishill and Henry le Veysyn in 1330 and 1338. (fn. 103) The Trinitarian friars of Oxford acquired lands and rents in 1359. (fn. 104) Wallingford priory and Goring priory also had interests, the latter holding the rectory estate from 1215 until the later 15th century. (fn. 105)

Later Freeholds

After the Dissolution Goring priory's possessions (distinct from the rectory) passed to Andrew Lydall and his heirs, (fn. 106) while Warren farm (137 a.), derived from the Grendon land sold to the de la Poles, remained attached to Ewelme until its sale by the Crown in 1817. (fn. 107) May's farm (459 a. in 1838) probably belonged to Edmund Rede's successors until 1579, when it was bought by William Dunch of Long Wittenham. In 1698 it passed by marriage to the Bisshopps of Parham (Sussex), and in 1838 was held by Mary Butler; it remained separate from the main manor in the 20th century, and for a time belonged to Turner's Court farm school. (fn. 108) Other freeholds were smaller, and from the late 18th century belonged to a succession of mostly absentee landlords, among them the bankers Joseph (d. 1814) and George Grote (d. 1830) of Badgemore. (fn. 109) In the early 20th century they included Howberrywood farm (158 a.), owned by Robert Fleming of Joyce Grove, 280 a. belonging to the neighbouring Ewelme Park estate, 105 a. owned by H.W. Wells of Wallingford, and 75 a. belonging to G.J. Inman of Highmoor Hall. (fn. 110) The glebe, restored to the rector from the late 15th century, covered c.60 a. near the church. (fn. 111)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century Nuffield's economy was predominantly agricultural, supporting half a dozen large farms in the 1850s. Sheep-and-corn husbandry was common, declining only during the agricultural depresssion of the early 20th century, when dairying expanded. Most farms were tenanted, although landowners usually kept in hand their valuable reserves of timber and underwood. A very limited number of trades and crafts served the local farming community and passing traffic on the Henley–Oxford road, site of the parish's only public house. As agricultural employment declined in the 20th century new opportunities arose at the golf club, farm school, prison, and nursing home (at Huntercombe Place), though in the early 21st century most inhabitants worked in professional occupations outside the parish.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 96)

From the Middle Ages Nuffield's once extensive woodlands, especially in the east of the parish, were gradually cleared and probably inclosed for farming, the process reflected in later field names such as Great and Little Stockings, the Grubbing, Oaken Grove field, and Knot Wood piddle. (fn. 112) Evidence of medieval open-field systems is lacking: tenants' yardlands may once have been farmed in common, but land surrounding the parish's dispersed farmsteads was almost certainly always held in private closes. (fn. 113) In the 1230s the lord William de Huntercombe (d. 1240) was licensed to inclose a large area of woodland with a ditch and hedge and to assart and cultivate it, (fn. 114) which if widely practised would account for the inclosed landscape of later maps. (fn. 115)

The boundaries of the medieval deer park surrounding Huntercombe manor house are unknown, but must have included Park Wood and the Lawn. Its origins lie probably in a royal grant of 114 a. of wood to William de Huntercombe in 1235, for which his heir paid £2 relief, and which apparently extended into Nettlebed and Swyncombe parishes towards Park Corner. (fn. 116) A forester mentioned around that time may have been employed to manage it. (fn. 117) Parkland belonging to neighbouring Swyncombe also extended into Nuffield (at Burton Park and Park Corner), while later field names suggest the presence of medieval rabbit warrens (Coneygear, Warren Hill), small-scale hay production (Haycroft, the Meadow), quarrying (Chalk Pit close, Pit ground), and tile-making (Great Tylers). (fn. 118) Nuffield Common covered c.113 a. in the centre of the parish, and in the absence of open fields provided the only significant area of common grazing. (fn. 119) Chalgrove's rights of common in Gangsdown are implied in extents and charters, (fn. 120) though to what extent they were exercised is uncertain.

In 1838 around four fifths of the parish's cultivable land was arable, with the rest divided roughly equally between grass (including commons) and woodland. (fn. 121) Arable farming remained dominant until the early 20th century, when the nationwide agricultural depression encouraged an increase in dairying and a conversion to grazing land. During the Second World War some grassland was ploughed up to meet the increased demand for food, and in the later 20th century the arable acreage was extended further. A few fields were also set aside for woodland plantations. (fn. 122)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

Demesne and tenant farming in Nuffield was typical of the area. A large arable acreage was cultivated by a combination of customary, family, and hired labour, while sheep were kept to manure the fallows and to provide meat, milk, and wool. Lack of hay and water probably limited the number of other livestock (especially cattle) that could be fed over winter, although some hay was brought in from neighbouring parishes. Grain (ground at the manorial windmill) was probably mostly consumed in the parish, judging from Nuffield's low levels of taxable wealth. Woodland was carefully managed by hired woodmen, generating income from sales of underwood, while Groveridge wood (in the south-east) remained under Crown management in 1438, as part of Benson manor. (fn. 123)

In 1086 the small Gangsdown manor contained land for two ploughteams, one (on the demesne) run by three servi, and the other (on the tenants' land) shared by four bordars. Pasture covered 24 a., and the manor's annual value (as in 1066) was 20s. (fn. 124) By 1279 the demesne was leased: ¾ yardland to two customary tenants, and the remaining 1¼ yardlands to unnamed free men, although 20 a. of wood was still managed directly by a woodman, who was entitled to collect foliage and graze livestock. Seven customary tenants paid cash rents totalling £2 18s. 7d., and between them provided ten workers for the lords' 'great harvest boonwork'. The manor's ten free tenants paid cash rents only, amounting to £3 19s. 3d. (fn. 125)

At Huntercombe, the lord (Walter de Huntercombe) held a hide and 100 a. in 1279, half in demesne and half occupied by five free and 16 customary tenants. The latter paid cash rents totalling £1 16s. 9d., mostly for smallholdings of 3 a. or less, as well as rents in kind including bread, ale, capons, and poultry. They also owed heavy labour services, especially at harvest when, between them, they provided the equivalent of c.65 days' work. Less onerous labour services included sheep-washing and shearing, haymaking, and weeding, while Robert Lovekin had to bring a horse and cart to carry dung to the fields, make four hurdles for the lord's sheepfold, carry wood for a day, fetch a cart-load of hay from Newnham Murren, make a quarter of malt and take it to the mill, and harrow and plough. The five free tenants paid rents totalling £2 4s. 9d. and a pound of cumin. (fn. 126)

In 1306 Walter de Huntercombe paid 4s. 2d. tax on his moveable possessions, the highest assessment in the vill, while four others (probably tenants) paid a further 4s. 2d. in all, suggesting a poor community with little capacity to generate surplus wealth. (fn. 127) On Walter's death in 1313 his 200 a. of demesne arable were worth a modest 3d. an acre, while his park generated underwood sales worth 1s. 8d. a year. In contrast to earlier, nine free tenants paid rents totalling £1 13s. 6d., and a single customary tenant and ten cottars paid £1 13s. 4d. in rent and 1s. 8d. for harvest works. The apparent conversion of customary land to free tenure, together with a 13s. decline in over-all rental income, suggests that the manor's tenants had won concessions, possibly because they were growing poorer. Certainly the manor's total recorded value had halved from c.£15 a year in 1271 to only £7 10s., for reasons which are not clear. (fn. 128)

By 1330 (when the manor was sold to Dorchester abbey) it included 200 a. of arable, 16 a. of woodland, 15 a. of parkland, and the rents of ten free tenants, the whole valued at £4 4s. 9d. A carucate (c.120 a.) and rents worth £1 6s. 2d., presumably from the customary tenants, were reserved to Nicholas de Huntercombe. (fn. 129) This further depreciation in the manor's value since 1313 presumably reflected either poor estate management or agricultural misfortune, and perhaps encouraged Nicholas to sell. Certainly in 1334 the vill contributed only 12s. 6d. to the lay subsidy, less than 1 per cent of the total for the hundred. (fn. 130)

After the Black Death Dorchester abbey's servants or lessees continued to grow wheat, barley, and oats, £5-worth of which were destroyed during a raid by Nicholas de Huntercombe in 1375, along with a cow, five heifers, twelve geese, and a pig. A bullock belonging to the tenant John Fairman was also killed. (fn. 131) During the 15th century wood sales still provided landowners with an intermittent income when woodland was sufficiently mature to be cut, (fn. 132) and individual farms were mentioned for the first time, amongst them May's (occupied by John Kentwood in the mid 15th century and by Robert Cheyne in 1492), (fn. 133) and Hayden farm (leased to the husbandman John Limebrenner). Limebrenner's annual rent fell from 20s. in 1465 to 17s. 8d. in 1476 and 11s. 4d. in 1483, demonstrating the falling land values typical of the period. (fn. 134) Permission to hold an annual Nuffield fair on 1 August was granted to the Trinitarian friars in 1366, but no evidence of its existence has been found. (fn. 135)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

The mixed farming of the Middle Ages continued in the period 1500–1800, with dairying probably increasing alongside traditional sheep-and-corn husbandry. Owners of Huntercombe manor held a large demesne farm which from the mid 17th century was usually leased, while the manor's tenanted land was gradually consolidated into a smaller number of larger holdings. Farms such as May's, Hayden, and Howberrywood are less well evidenced, but were usually also leased. Wood sales remained an important source of income for landowners, while grazing on Nuffield Common was carefully regulated by the manor court.

During the 1530s Dorchester abbey leased the Huntercombe demesne to Thomas Spyer for £3 6s. 8d. a year, collecting rents totalling £3 18s. 2d. from the tenants of ten copyholds and two freeholds. (fn. 136) The manor was probably especially valued for its woodland: when sold to Richard Taverner in 1545 it contained seven named woods, of which one was leased to a local tenant, Thomas Andrew. Other coppices included Park Wood (part of the medieval deer park, though probably no longer used for hunting), and Cony Herthe or Coneygear, whose name implies use as a rabbit warren. (fn. 137) In 1569 Richard Spyer sold wood from Huntercombe to a Wallingford river trader. (fn. 138)

The Spyers continued to run Huntercombe farm directly, Thomas Spyer (d. 1572) making several bequests of sheep, cattle, and wheat. (fn. 139) Earlier a woman's pigs were impounded following damage done to his corn, but were restored on payment of a fine. (fn. 140) Other farms, including May's and Magdalen College's Hayden farm, were probably leased, (fn. 141) John Matthew (d. 1569) of May's leaving substantial stock worth £328, encompassing breeding cattle, c.320 sheep, barley, and malt. At a lesser level the husbandman John Croxford (d. 1570) left goods worth £14 10s. and a share-farming agreement, while the labourer John Halley (d. 1587) bequeathed modest goods worth under £5, including a cow, a bullock, and six sheep. (fn. 142)

John Spyer retained 495 a. of Huntercombe farm in hand in 1665, including the manor house and grounds (5 a.), arable and pasture (265 a.), and woodland (225 a.). A further 243 a. were leased to c.12 customary tenants in plots ranging from 2 to 47 acres. Tenants were admitted for life at the lord's will or by copyhold for three lives, for which they paid an initial entry fine or heriot, an annual cash rent, two capons or pullets at Christmas, and a day's service at harvest. Among them was John Lewis, who in 1640 took a house and 18 a. for the lives of himself, his wife Margaret, and son John at an annual rent of £5, paying £20 at admission, and promising to hedge his inclosure. Closes over all varied greatly in size, but were typically 5–20 a., with few exceeding 30 acres. Unlike in the Middle Ages, only a small amount of land was held by free tenure. (fn. 143)

Spyer may have commissioned the survey of 1665 in readiness for leasing his home farm, since soon afterwards the manor house was occupied by Edward Leaver. His kinsman Robert Leaver occupied the 472-a. May's farm, (fn. 144) which had additional land in Benson and included 106 a. of woodland: both May's and Huntercombe farms were then more heavily wooded than later, despite some earlier clearance. (fn. 145) Magdalen College grubbed up another 30 a. near Hayden Farm later in the century, and c.1700 let the farm for seven years at £50 a year. The college retained its timber and underwood, but allowed the tenant sufficient wood for fuel, repairs, and maintaining fences. (fn. 146) Howberrywood farm, covering 46 a. in ten closes in the far south-east of the parish, was also leased. (fn. 147)

Seventeenth-century inventories illustrate the mixed farming typical of the Chilterns. Sheep were the most common livestock, producing wool which was often spun by household members. Small numbers of valuable dairy cattle supported cheese-making, and many inhabitants kept a few poultry and pigs (for bacon). Horses were generally used for ploughing and carting. The main cereal crops were barley (some of it malted), wheat, and rye, with oats, peas, vetches, and hay grown for fodder; sheep were folded on the arable using hurdles, while manure was also carted to the fields in dungpots. Farming was sometimes combined with craftwork, as by the pickmaker William Croxford (d. 1639) and the wheelwright Robert Fennell (d. 1644), while at least one inhabitant kept bees on a commercial scale. Debts owed by the husbandman Philip Croxford (d. 1667) reveal the small-scale credit networks which must have been common, with modest sums owed to (among others) Nuffield's rector, a local blacksmith, and a Henley widow. (fn. 148)

In the 18th century the acreage of Huntercombe's demesne farm remained unchanged, though small-scale woodland clearance continued, and tenants' lands were consolidated into five principal holdings of 20–73 a. each, a single smallholding of 3 a., and several cottage holdings. Leases in the 1760s were renewed for terms of between 8 and 19 years at rents of c.10s.–16s. an acre, while woodland was kept in hand and coppiced every eight years, producing an annual income of c.£175. (fn. 149) Tenants enjoyed unlimited grazing rights for cattle on Nuffield Common, though pigs had to be ringed and sheep were stinted, with heavy fines for those caught agisting non-commonable sheep. An unsuccessful challenge by the lord against one inhabitant's sheep-grazing was followed in 1770 by his purchase of the grazing rights attached to particular holdings. Tenants of May's farm held limited common rights in the common's western part, though in the late 18th century tenants of Hayden farm may have had their rights curtailed. (fn. 150)

Huntercombe farm changed hands regularly in the 18th century, as lords sought to maximize the rent. Joseph Goodchild of Woodcote took over from Francis Steel in 1762, paying £135 a year or c.10s. an acre. In 1772 (shortly before the expiry of Goodchild's 11-year term) William Newell of Redpits in Bix offered 14s. an acre for the farm, but apparently lost out to Henry Read; he in turn was succeeded by John Lewis, one of a long-standing local family who took a 14-year lease in 1784 at an annual rent of £178 10s. (fn. 151) Half a dozen other farms were similarly leased by the parish's largely absentee landowners, (fn. 152) amongst them the newly created Warren farm, whose ancient rabbit warren was ploughed up in the 1720s. (fn. 153) The manor's cottagers paid annual rents of 2s. 6d., 5s. or 10s. for poor and run-down houses on the common, though one, the labourer Richard Arthur (d. 1789), also held houses in Benson and Nettlebed. Possibly he sublet his Nuffield cottage to a neighbour or itinerant farm hand. (fn. 154)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

Arable farming reached its peak in the mid 19th century, when six large farms were run from the parish. Huntercombe farm (248 a.) was retained by John Lewis until the 1830s, when the lord resumed the former practice of leasing it to short-term tenants. Thomas Cozens employed 10 labourers there in 1851, when the farm was over 90 per cent arable. May's (459 a.), Hayden (200 a.), and Howberrywood (182 a.) farms were also chiefly arable, and following the departure of some long-standing tenants were similarly leased for relatively short terms. (fn. 155) The 135-a.Warren farm (wholly arable in 1838) was sold to its tenant John Franklin in 1817, while Warren Hill farm (87 a.) was sold to an owner-occupier in 1833. Smaller farms were run by tenants of the Crown Inn (63 a.) and glebe (60 a.), although the independent Ambrose farm (carved from May's) proved short-lived. (fn. 156)

In 1837 about a fifth of the parish's arable was sown with wheat (338 a.), with smaller quantities of barley, seeds, turnips, sainfoin, oats, and vetches. Another 113 a. were bare fallow. (fn. 157) By 1870 the fallow was almost eliminated, although a larger area of grass (240 a.) was mown for hay. Wheat, barley, and oats remained the main cereal crops, occupying almost two thirds of the sown area, with turnips, swedes, and rape grown for fodder. Sheep were the principal livestock, with an aggregate flock of 824; almost a hundred pigs and 42 horses were also kept, although the dairy herd numbered only twelve. Little immediate change took place following the onset of agricultural depression soon after, and in 1900 sheep-and-corn husbandry remained widespread, while dairying had barely increased. No allotments were provided for poorer inhabitants, and there was little diversification into other crops or fruit. (fn. 158)

Farm work remained the main source of employment for around two thirds of Nuffield's inhabitants throughout the 19th century, the rest employed in domestic service or trades and crafts, and a very few in professional occupations such as medicine or teaching. (fn. 159) Nuffield Common remained an important resource for many, who cut furze there for fuel, grazed sheep and goats, and occasionally poached rabbits; (fn. 160) such practices were largely ended by its sale in 1894 and by the subsequent construction of the golf course, (fn. 161) while agricultural employment, too, began to decline, signalled by the closure of Huntercombe farm in 1896 and the sale of its stock. In 1901 the farmhouse was occupied by the newly-arrived steward of the golf club, and by 1930 the number of regular farm workers in the parish had fallen from around 50 to 19. (fn. 162)

In the early 20th century the parish's principal farms remained Hayden, Howberrywood, May's, Warren, and Warren Hill, all of them tenanted, while substantial acreages were managed from Ewelme Park, Timbers, and Turner's Court farms in neighbouring parishes. (fn. 163) Extensive consolidation took place before the Second World War: Warren farm was taken over by Ewelme Park and its farmhouse converted into cottages, while May's and Warren Hill were bought by Turner's Court farm school. (fn. 164) Agriculture also became more pastoral as the depression squeezed arable farmers' profits. Between 1910 and 1930 grass increased from less than a third to around three fifths of the parish's cultivable land, while the sheep flock fell from 1,335 to 92, and the cattle herd grew from 44 to 247. Substantial numbers of pigs and poultry were also kept. (fn. 165)

Amalgamation meant that by 1941 several of the parish's farms were managed from beyond its borders as part of more extensive operations. Benson's Turner's Court farm (847 a.), including May's and Warren Hill, was c.50 per cent arable with a pedigree herd of Ayrshire cattle, and was run as a training colony for boys aged 14–18, who did most of the work under the supervision of instructors. (fn. 166) Newnham Murren's Timbers farm (514 a.), which included the former glebe and part of the manorial demesne, was owned by Viscount Nuffield and leased to the long-standing tenant Bob Hayward, who sold wholesale milk from a large dairy herd of Shorthorns. Sheep, pigs, and poultry were also kept, and a system of ley farming was adopted whereby the arable was laid to grass for 7, 13, or 20 years. (fn. 167) The Flemings' English farm (444 a.), incorporating Howberrywood, was mostly a dairy farm before the war, though by 1941 the tenant had reduced the stock and ploughed up a considerable acreage of grass. Smaller farms included Hayden (183 a.) and Huntercombe End (136 a.), the latter run as a hobby farm by a retired businessman: both pursued largely dairying, with some cultivation of fodder crops. In all c.40 workers were employed on the parish's farms. (fn. 168)

The former Crown Inn by the Oxford– Henley road, adjoining a former smithy.

During the later 20th century arable farming steadily increased. At Timbers in 1958 the emphasis was still on milk, beef, lambs, pigs, and poultry, though more than a third (185 a.) was under wheat. (fn. 169) Thereafter the parish's total acreage devoted to cereal crops (mainly barley and wheat) rose from about two fifths in 1960 to two thirds in 1970, falling back to a half by 1988. By then wheat had overtaken barley, accompanied by new crops including oilseed rape, while the area of woodland was considerably enlarged. Over the same period (1960–88) the number of cattle fell from 600 to 257, while sheep, pigs, and poultry all increased: some farms specialized in poultry or livestock, and in all the sector employed 26 farmers and workers. Sales by landowners, including that of Timbers farm in 1979, meant that more than 90 per cent of the parish's farmland was owner-occupied. (fn. 170)

TRADES, CRAFTS, AND RETAILING

From the Middle Ages Nuffield was predominantly agricultural, and few trades and crafts are recorded. The Crown Inn by the Henley road existed by the 1720s and probably much earlier, (fn. 171) and was sometimes later managed with an adjoining smithy. (fn. 172) Seventeenth-century craftsmen included a pickmaker who left shop timber and working tools worth £7, and a wheelwright whose customers included the lord John Spyer and a Dorchester man. (fn. 173) Woodmen and blacksmiths were mentioned in the 18th century. (fn. 174)

In 1801 six people (just 4 per cent of the population) relied mainly on trade or craft, and only 4 out of 42 families in 1821. (fn. 175) Resident tradesmen twenty years later included three smiths, two brickmakers, two grocers, two shoemakers, a baker, and a potter, although some probably worked in neighbouring Nettlebed. (fn. 176) In 1851 c.14 per cent of inhabitants were tradespeople, among them a laundress, a seamstress, and two sawyers, while other late 19th-century occupations included those of carpenter, cabinet maker, gardener, and brazier. The blacksmith William Francis opened a grocer's shop on Gangsdown Hill in the 1870s, and though it closed following his death his forge next to the Crown Inn was continued by his sons, remaining open until the late 1920s. (fn. 177) A motor garage and petrol filling station opened around the same time may have taken over some of the forge's work, and continued until the late 20th century. A shop run by Arthur Stallwood in the 1930s was probably short-lived, (fn. 178) although the newly opened post office continued until c.1970. (fn. 179)

The golf club and farm school provided additional employment in the early 20th century, supplemented by the prison (opened in 1946) and Huntercombe Place (converted into a nursing home in 1989–90). (fn. 180) Following the post office's closure the parish lacked shops, although the Crown remained popular until its closure in 2013, and an antiques centre was mentioned in 1992. (fn. 181) In the early 21st century most working inhabitants were employed in managerial or professsional occupations outside the parish, though around 100 people occupied lower-skilled or more routine jobs. (fn. 182)

MILLING

A mill mentioned in 1279 was presumably a predecessor of the manorial windmill recorded in 1586, which continued throughout the 17th century. (fn. 183) It reportedly stood on Nuffield Common west of the 'rough road' to the church, its remains still discernible in the early 20th century. (fn. 184) Nonetheless it appeared neither on estate maps of 1665 and 1770 nor on 18th-century county maps, (fn. 185) and no further references have been found.

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

Nuffield's scattered medieval population comprised mostly free and customary tenants of Gangsdown and Huntercombe manors. (fn. 186) Gangsdown's seven villein tenants in 1279 held between 3 a. and 1¾ yardlands each for cash rents and light labour services, exacted presumeably on the lords' demesnes in Chalgrove, where tenants also attended the manor court. Their neighbours included ten free tenants who together held around two thirds of Gangsdown's farmland in parcels of between 1/4 yardland and 31/4 yardlands. One (Hugh Colegrim) held under a probably non-resident intermediary and occupied an additional customary holding, while the holdings of two other free tenants were to be held in villeinage after their deaths, for reasons which were not given. The recent division of Chalgrove manor meant that around half the tenants (both free and unfree) held of one of the manors' two halves, with just a handful holding of both. (fn. 187)

Huntercombe's sixteen unfree tenants in 1279 were mostly heavily burdened smallholders, owing rents in cash and kind, and a variety of labour services exacted on their resident lord's demesne. Most held only ½ a. to 3 a., and must have been extremely poor, supplementing their income by labouring or non-agricultural activities. A partial exception was John White, who had 18 a. and paid tax in 1306, suggesting that he produced a marketable surplus. Five free tenants held a yardland or half yardland, and one sublet 2 a., although the 6d. tax paid by the freeholders Walter Field and Walter Coleman in 1306 suggests very modest prosperity. The community was probably close-knit, its villein tenants including four members of the Cook family, three Berkers (meaning shepherd), and two Lovekins. (fn. 188) Even so some people (as later) probably occupied isolated outlying farms. (fn. 189)

Given their surname the lordly Huntercombe family were presumably both local and resident, and maintained a deer park and a manor house. (fn. 190) Walter de Huntercombe (d. 1313) was often away on royal service, however, and in 1304 trespassers broke into his park, killed deer and horses, and assaulted the manor's servants. (fn. 191) Walter's successor Nicholas de Huntercombe may have been involved in a similar raid on Rewley abbey's Nettlebed property in 1322, in which several Huntercombe men participated. (fn. 192) His heavy debts forced his sale of the manor to Dorchester abbey in 1330, although he may have continued to live in Nuffield as the abbey's subtenant. (fn. 193) A later Nicholas de Huntercombe disputed the abbey's title, and in 1375 led an attack on its property with 40 armed men: the gang fortified the manor house and remained there for a fortnight, plundering and destroying goods and threatening to kill the abbot and his servants. (fn. 194)

The 1381 poll tax was paid by seven inhabitants in Gangsdown and seventeen in Huntercombe, but while the latter paid the standard amount of 1s. per head, at Gangsdown the tax was levied unevenly amongst household members, presumably reflecting a community decision. Thus William Merche paid 2s. as head of household, leaving his sons Thomas and William to pay 6d. each, while William at Hyde (almost certainly an occupant of the outlying Hayden Farm) paid 2s. 4d. for himself and his wife, reducing his daughter's share to only 8d. Half of the parish's taxpayers at that date were married couples, with only a quarter not part of a family group. William at Hyde was probably descended from customary tenants recorded in 1279, and William Costard may have been a descendant of one of the rioters of 1322. Few resident families were of such long standing, however, and Huntercombe taxpayers such as the Butlers, Carters, Hays, Martins, and Smarts were almost certainly newcomers, reflecting the typical changes which followed the Black Death. (fn. 195)

1500–1800

In the early 16th century the parish's wealthiest inhabitant was Thomas Spyer, lessee of Dorchester abbey's Huntercombe farm. The family came from Ewelme, with which they initially maintained close ties following their purchase of Huntercombe manor: (fn. 196) Thomas (d. 1572) was buried at Ewelme, and left money to the churches of Ewelme, Benson, and Nettlebed. His son Ralph (d. 1589), though also buried at Ewelme, remembered Nuffield's church and poor in his will, (fn. 197) and other family members showed increasing local attachment, the husbandman Ralph Spyer and his widow Joan (d. 1557) being both buried at Nuffield. Their wills were witnessed by parish neighbours, (fn. 198) amongst them Robert Eyre (one of the few parishioners to rival the Spyers in wealth), and John Matthew (d. 1569) of May's farm. (fn. 199)

Matthew's descendants seem not to have remained in the parish for long, and rapid turnover of families (already evident in the later Middle Ages) continued into the early 16th century, when taxpayers holding land under Dorchester abbey included Thomas Andrew, Thomas Belson, John Castle, and Thomas Sharp. Their surnames recurred only rarely in later decades, with only William Willis apparently establishing a local dynasty. (fn. 200) By contrast the later 16th century saw the appearance of several long-lasting families, including the Croxfords, Fennells, and Halleys. The Croxfords and Halleys intermarried, their wills demonstrating a typical mix of close local connections and of tenurial and family links outside the parish. (fn. 201)

The Spyers continued as resident lords and large-scale farmers into the mid 17th century, although during Ralph Spyer's minority Huntercombe manor house was occasionally occupied by some of the Carletons of Brightwell Baldwin. One was Dudley Carleton (d. 1632), future Viscount Dorchester, who enjoyed 'airing himself on the Chiltern hills'. (fn. 202) Ralph (d. 1623) recovered possession in 1611, but his son John Spyer (d. 1674) preferred Holcombe Grange in Drayton St Leonard, and in 1665 leased the manor house to Edward Leaver, (fn. 203) one of a prominent Nuffield family which in the 17th and 18th centuries occupied both May's and Huntercombe Farms. Both were among the parish's larger houses, taxed respectively on ten and three hearths. (fn. 204)

By contrast most other houses in the parish were taxed on only one or two hearths, although their occupants included some prosperous farmers. Philip Croxford (d. 1667), taxed on one hearth only, left goods worth c.£141, while Christopher Hedges (d. 1684), assessed on two, left over £327-worth. Their possessions, however, consisted chiefly of grain and stock rather than household goods, and probate documents confirm that many of the parish's 17th-century houses were both small and modestly furnished. (fn. 205) Poorer inhabitants included the labourer William Halley (d. 1675), who occupied a run-down cottage and left goods worth only £11 3s. (fn. 206) Another poor labourer, left partially incapacitated by a gun accident and in debt to a surgeon, was unable to support his wife and six children. (fn. 207)

Two soldiers killed during the Civil War were buried in the parish in 1643, presumably following a skirmish, and in 1648 the inhabitants were forced to contribute £4 10s. to the garrison at Wallingford. (fn. 208) More normal daily life was regulated by the Huntercombe manor court, which enforced removal of nuisances, prohibited subletting and encroachments on the waste, policed grazing, and ordered repair of houses. Ralph Willis was required to fill in holes made by his pigs rootling on the common, and another inhabitant (John Small) was presented for keeping an unlicensed alehouse, while stocks and a ducking-stool were mentioned in 1645, and a prison in 1650. Such courts provided a social focus for a scattered community, although their sessions were relatively infrequent, and were probably less important for tenants of other landowners. (fn. 209) The church, too, provided only a partial focus, with some parishioners (as in the Middle Ages) attending nearer churches elsewhere. Conversely, some outsiders worshipped at Nuffield. (fn. 210)

Poverty and crime remained prominent concerns in the 18th century. Charity towards those deemed a burden was sometimes withheld: a man with four young children had his allowance stopped in 1701, while in 1727 an Irish widow's sick child was removed from the Crown Inn to Ewelme, and left under a wall in the snow. (fn. 211) Movement of migrant workers was carefully monitored, a labourer hired by John Croxford at Thame hiring fair remaining in the parish for only a year before being removed to Bix. Others returned to Nuffield from parishes no longer able to support them, including Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 212) Occasional instances of theft and violence included highway robbery and poaching, (fn. 213) to combat which the then non-resident lord employed a gamekeeper. Recreational hunting was pursued both by the rector and by the tenant of May's farm. (fn. 214)

Most tenant farmers in the early 18th century were moderately prosperous, the yeoman John Halley (d. 1723) leaving goods worth £44 15s. 6d., although only the lessees of Huntercombe farm were conspicuously well off. (fn. 215) As larger farms emerged social and economic differences probably increased: surviving 18th-century wills include several made by labourers, men who generally had some land or goods but who presumably worked for wages rather than on their own account. Examples include Ralph Warner (d. 1770), a smallholder and labourer on the Huntercombe estate, and his relative Richard Arthur (d. 1789). (fn. 216) Over the period long-standing families such as the Croxfords and Fennells gradually gave way to newcomers such as the Husseys and Goodchilds, although the Willis family continued. (fn. 217)

Since 1800

The largest proprietors in the early 19th century were the non-resident lord, the occupants of May's, Huntercombe, and Howberrywood farms, and (as holder of the glebe and tithes) the rector, each of whom paid between £10 and £20 land tax. (fn. 218) Together they were major employers of labour and servants: in 1851 May's farm alone employed 33 labourers, and 24 live-in servants were reported over all. Many lesser inhabitants endured considerable hardship, and in 1851 eleven were specifically described as paupers. (fn. 219) Poverty fuelled continuing acts of petty violence and theft: in 1820 the bailiff of May's farm suspected a hired carter of stealing wheat, while in 1828 two labourers stole bacon, bread, and cheese from William Hussey. (fn. 220)

Despite the continued turnover of surnames, in the mid 19th century more than half the population had been born in the parish, with around 86 per cent drawn from within Oxfordshire. Others came mostly from Berkshire, with very few from further afield. Change in subsequent decades was gradual, and in 1891 three quarters of inhabitants were still county-born. (fn. 221) The parish's community life is poorly recorded, but was most likely dominated by church and pub. An apparently short-lived Friendly Society was mentioned in 1891–5, (fn. 222) and cricket was played on the common c.1900, when inhabitants were assured that games would continue following the construction of Huntercombe golf course. (fn. 223)

Huntercombe Golf Club opened in 1901, its course designed by the golf professional Willie Park junior. (fn. 224) Its wealthy clientele contributed to the parish's incipient gentrification, which was accelerated by the building of small country houses at Huntercombe Place and Merrow Mount (Fig. 98). (fn. 225) William Morris bought the golf club in 1925, living in its architect-designed clubhouse (Fig. 100) before moving to Merrow Mount (renamed Nuffield Place) in 1933. (fn. 226) His renowned philanthropy extended to his adopted parish, where he made gifts to the church and school and paid for Christmas parties and treats for the children. (fn. 227) His attempt to compensate inhabitants for loss of common rights was not wholly successful, however, and residents continued to cut gorse and dump rubbish on the common to the annoyance of the golf club. (fn. 228) The farm school at Turner's Court had little social impact, its boys (many of them from difficult backgrounds) looking mainly to Wallingford for outside entertainment. (fn. 229)

Huntercombe golf club's former clubhouse, designed by Oswald Milne, and occupied by William Morris 1925–33.

During the Second World War Huntercombe Place was requisitioned, and an internment camp (which briefly held Rudolf Hess) was set up in its grounds. The site reopened as a borstal in 1946, to the reported horror of Morris's wife Lady Nuffield, (fn. 230) and in 1983 inhabitants expressed concern at plans to increase the number of inmates to 240, claiming in 1992 that expansion had led to an 'intolerable increase in noise'. (fn. 231) The prison (Fig. 97) remained a young offender institution until 2010, when it reopened as a Category C adult prison with a capacity of 372, holding foreign nationals facing deportation. (fn. 232) Huntercombe Place itself was converted in 1989–90 into a nursing home for 54 residents, (fn. 233) while Nuffield Place opened as a National Trust property in 2012. (fn. 234) Despite the professional background of many inhabitants the continued availability of council houses ensured that the parish remained socially mixed, and in the 1960s–70s between a quarter and a third of households claimed coal money. (fn. 235) The parish council was active in organizing events, improving services, and tackling local problems including vandalism and litter. (fn. 236)

EDUCATION

A charity providing £30 a year to clothe and educate ten poor children (five boys and five girls), and to apprentice two of them annually, was established by Elizabeth Gibbons (née Spyer) and her husband in 1707. (fn. 237) It was not mentioned later, and perhaps never took effect. Offertory money was sometimes used to place poor children in school in the 1750s, while in 1802 some children attended school in a neighbouring parish, probably Nettlebed. (fn. 238) A Nuffield day school supported by the rector and parents existed by 1808–15, teaching up to 20 young children, but closed by 1818 when the poor were 'ready to embrace any means of education which are offered them'. (fn. 239) A school mentioned in 1823 may have been even more short-lived. (fn. 240)

The former school in Nuffield village, built in 1892 and closed in 1992.

A new Anglican day school supported by voluntary contributions opened in Nuffield in 1832, attended by 14 boys and 21 girls. Several more children attended Sunday school, while an infant school taught 3 boys and 4 girls at their parents' expense. (fn. 241) A schoolmistress mentioned in 1841 lived presumably in the teacher's house east of the church; the adjoining school had c.45 children in 1853, when the mistress was the long-serving Charlotte D'Oyly, who remained for around twelve years. (fn. 242) The Sunday school had 70 children the following year, while members of a twice-weekly winter evening class run by the rector were reportedly 'attentive and thankful'. (fn. 243) The evening classes ended in the 1880s, but the Sunday school continued. (fn. 244)

In 1860 the day school received a government grant of £14 10s., donations of £26 7s., and fees of £7 14s. 8d. Average attendance fell to 30 by 1871 when the school apparently lacked a certificated teacher, (fn. 245) and in 1874 (as at Nettlebed) the ratepayers proposed a School Board, which took over the school's management two years later. (fn. 246) In 1892 a new Board school was opened a little further along the street, brick-built and with a central bell-turret and two classrooms; in 1894 it was only half full, however, with an average attendance of 47. Half of its £90 annual income (spent mostly on the teacher's salary) was raised locally, the rest coming from government. (fn. 247) Staff turnover was high, (fn. 248) but in the early 20th century average attendance rose to c.60 and the government grant to £89, and in 1914 (when it was run by the local authority) the inspector reported positively. (fn. 249)

Later reports were mixed, and in the mid 1920s the school suffered from severe bouts of sickness. The headmistress struggled to teach a mixed-ability class aged from seven to fourteen, and in 1929 the school was reorganized for mixed junior and infant children, the seniors going to Nettlebed. Under a new headmistress the children made impressive progress, undermined in the later 1930s by her frequent ill health, (fn. 250) and in 1931 Viscount Nuffield made a donation to the sports fund, his first gift to the school. (fn. 251) The school continued (latterly as a primary school) until 1992. (fn. 252)

CHARITIES AND POOR RELIEF

Some of Nuffield's earliest charitable bequests came from owners of English farm in Newnham Murren. Ann Eton (d. 1547) left a cow and 6s. 8d. to Nuffield's poor, while Ralph Warcopp (d. 1605) left £10 for distribution at his burial and 20 nobles (£6 13s. 4d.) to set the poor to work with flax, hemp, and wool. (fn. 253) In the 18th century the churchwardens and overseers distributed the interest to poor families not on poor relief, but by the 1760s the charity had been lost through insolvency. (fn. 254) Ralph Spyer (d. 1589), lord of Huntercombe, left 10s. to the poor, followed by comparable bequests by the rectors Robert Butler (d. 1609), Robert Godfrey (d. 1659), and Robert Sawyer (d. 1668), (fn. 255) while Mary Spyer (d. 1699) left an annual £5 rent charge to apprentice a poor child to an urban trade. The charity was properly applied in 1738 but was rarely used by the late 18th century, with no applications between 1803 and the early 1820s. (fn. 256) It was still mentioned in 1852, but seems to have lapsed thereafter. (fn. 257)

A workhouse at Satwell in Rotherfield Greys parish briefly housed Nuffield's poor in the 1740s, (fn. 258) and by the late 18th century the cost of parish poor relief was c.£144 a year, (fn. 259) rising to £251 by 1803; 57 people (including 24 children) were then receiving permanent relief, and 14 were helped occasionally, over all an unusually high proportion of the population (51 per cent). Eighteen non-residents were also helped, suggesting considerable hardship among the parish's agricultural workers. (fn. 260) Expenditure more than doubled to £554 in 1813, when 22 people were relieved permanently and 35 occasionally, c.37 per cent of the population. (fn. 261) It then fell to £352 in 1815, fluctuating considerably (from £345 to £518) until 1823, with an annual average of c.£431. Costs thereafter became less variable, averaging £474 to 1832. In 1834 they were £369, (fn. 262) responsibility passing thereafter to the new Henley Poor Law Union. (fn. 263)

During the 20th century Lord Nuffield funded a coal charity, which was intended to replace parishioners' rights to cut wood on Nuffield Common. In 1962 a total of 39 inhabitants met the twelve-months' residence requirement, and received 6s. 2d. each. Following Lord Nuffield's death the charity was continued by Huntercombe golf club, which contributed £12 a year, and in 1979 proposed ending the charity in return for a one-off payment of £100 to the parish council. Instead it was decided that £12 a year should be paid into a village fund rather than distributed to parishioners. (fn. 264) Other late 20th-century charities were established using funds from the sales of Nuffield primary school and Turner's Court farm school. (fn. 265)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Nuffield had its own church by the early 12th century. The benefice was appropriated in 1215 to Goring priory, and vicars were appointed until the late 15th century when it reverted to being a moderately endowed rectory. In the meantime Trinitarian friars from Oxford obtained the advowson from Goring priory in 1362, and perhaps maintained a house in the parish, where they also held land. Nuffield's later rectors were generally well educated and included some non-resident pluralists, and after the Reformation neither Catholicism nor Protestant Nonconformity gained much ground until the 19th century, when Dissent surfaced briefly. The benefice was absorbed from 2006 into a large team ministry.

CHURCH ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

Though probably formerly dependent on Benson, Nuffield acquired its own church by the early 12th century, the date of the earliest surviving fabric and of the cylindrical Norman font. (fn. 266) Its jurisdiction seems at first to have extended southwards into Mongewell, whose dead were buried at Nuffield or Newnham Murren until Mongewell church became independent c.1184. (fn. 267) The founder may have been one of the Bolbecs of Crowmarsh Gifford, since Walter Bolbec gave both Crowmarsh and Nuffield churches to Goring priory some time before 1181, most likely in the early 12th century. (fn. 268) In 1215 the nuns were licensed to appropriate it to provide for their clothing, and the bishop ordained a perpetual vicarage, (fn. 269) but in the later 15th century both arrangements lapsed for unknown reasons. The influence of the Trinitarian friars (patrons from 1362) may account for a change in the church's dedication from St Peter to the Holy Trinity. (fn. 270)

The ecclesiastical parish continued unaltered after the early Middle Ages, remaining in Henley rural deanery except for a short-lived transfer to the deanery of Nettlebed (1852–74). The church retained its own incumbent until 2006, when the rector of a large benefice based at Nettlebed was appointed priest-in-charge. (fn. 271)

Advowson

Goring priory retained the patronage until granting it to the Trinitarian friars in 1362. (fn. 272) The friars presented for the last time in 1510, and in 1551 the king granted the advowson to Sir Thomas Wroth, knight of the privy chamber. (fn. 273) He immediately sold it to the lord of Huntercombe, Thomas Spyer, the patron in 1556, and thereafter it descended with the manor. The king presented during minorities in the Spyer family, nominating George Carleton (the future bishop of Chichester) in 1609 even though the advowson had been included in the wardship granted to Carleton's relative George Carleton of Brightwell Baldwin. (fn. 274)

The bishop of Oxford presented in 1662 claiming that ownership of the advowson was in doubt, but it was recovered by John Spyer before the next presentation in 1668, and passed first to his widow Mary, and then jointly to William Gibbons and Richard Jones, the husbands respectively of John Spyer's daughter and granddaughter. In 1760 the patron was Dame Katherine Champion, Richard Jones the younger's widow, from whom it passed (with the manor) to William Langham (d. 1791). Elizabeth Langham (née Burdett) leased and then sold the patronage, which was held by Henry Hopkins and Robert Fisher in 1826. She later recovered it, and in the late 19th century the Lord Chancellor presented on behalf of Sir James Hay Langham, who was declared insane. (fn. 275)

In 1894 the advowson was sold with the manor to H.H. Gardiner, and subsequently passed to the Norwich Union insurance company. It was not bought by William Morris, and in 1930 was sold by Sir George Morse to the Revd P.E. Warrington. He gave it in 1937 to the Martyrs' Memorial and Church of England Trust, the patrons in 2008. (fn. 276)

Glebe, Tithes, and Vicarage

Though not wealthy, in the mid 13th century Nuffield was among the better-off benefices in Henley deanery, valued in 1254 at 10 marks (£6 13s. 4d.) a year, the same as Bix Brand and Rotherfield Greys. In 1291 its valuation was only £4 8s. 4d., including 10s. owed to Wallingford priory and 5s. to Dorchester abbey; (fn. 277) both payments were for tithes, of which the priory's (in Gangsdown) had perhaps been given by Miles Crispin. In 1341 glebe and small tithes made up £2 13s. 4d. of the income, and the earlier valuation of £3 13s. 4d. (excluding the priory's and abbey's portions) was repeated in 1428. (fn. 278) In 1526 the living's gross income was reckoned at £8, and in 1535 at £9. (fn. 279)

The endowment included a sizeable glebe. Walter Bolbec's gift of the church to Goring priory included half a yardland, a house (masura), and a hide containing a furlong (cultura) extending from the church to the 'old ditch'. (fn. 280) The patron of Mongewell church gave an additional yardland before 1184, in return for Mongewell's parochial independence. (fn. 281) By the 17th century the glebe comprised five contiguous closes called Priest field, West field, North field, Rattles, and Rye piddle, estimated at c.50 a. and located along the parish's southern boundary close to the church. In 1805 roughly the same area (reckoned at 60 a.) was ring-fenced, and later leased. The glebe was sold in 1924. (fn. 282)

The vicarage ordained in 1215 was worth 5 marks (£3 6s. 8d.) a year, and included altar dues, some glebe (with buildings and gardens), and grain tithes from specified lands. (fn. 283) In 1291 it was nevertheless assessed at only £1. (fn. 284) The parish's remaining tithes were retained by Goring priory, and were excluded from its grant to the Trinitarian friars in 1362, although the nuns later gave 15s.-worth of tithes in Nuffield and Goring to St Frideswide's priory, Oxford. (fn. 285) The Crown gave Wallingford priory's 10s.-worth of tithes in Gangsdown to Thomas Wolsey, archbishop of York, in 1528, and to St George's Chapel, Windsor, in 1532, (fn. 286) while the payment to Dorchester abbey (then 2s. 6d. a year) passed to Richard Taverner with Huntercombe manor. (fn. 287)

Those payments apart, from the 15th century both tithes and glebe belonged to the rector. In the early 19th century the living was valued at c.£300 depending on the harvest, (fn. 288) and in 1838 the tithes were commuted for a £446 rent charge, contributing to a gross income of £521 in 1860. (fn. 289) In 1900 the rector's net income was only £220, rising to £517 in 1935 but falling to £406 in 1951–2. (fn. 290)

Rectory House

The now-demolished rectory house stood in extensive grounds south-west of the church, and in 1602 had an adjoining barn, stable, orchard, and garden. (fn. 291) That was presumably the brick-and-flint house with a tiled roof mentioned in 1805, which was considerably enlarged by William Toovey Hopkins (rector 1826–67): in 1847 he was said to occupy a 'pretty residence', recently built. Further improvements were carried out in 1874 and 1897, after which the house was described as a 'plain building in the Georgian style', cement-faced and slated. (fn. 292) By the early 20th century it was too large for the rector to maintain, and in 1937 it was demolished. A new five-bayed rectory house of brick and tile was built opposite the church in 1939–40, with a central pedimented doorway. (fn. 293)

PASTORAL CARE AND RELIGIOUS LIFE

The Middle Ages