Pages 393-421

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

WARBOROUGH

Warborough is a rural parish midway between Dorchester and Benson (each c.3 km distant), characterized by a mainly flat, open landscape of large fields and riverside meadows. (fn. 1) The parish contains two formerly separate settlements: Warborough itself and, close to the Thames in the south, the hamlet of Shillingford. Following modern housing development, the two places now meet along the Thame-Wallingford road.

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Warborough formed a core part of Benson's extensive royal estate, and the Crown remained the major landowner until the 17th century. Subsequent lords of Benson retained land in the parish until the 1930s, but from the 16th century the most substantial estate was owned by St Johns College, Oxford. Consequently the parish has never had resident gentry. Its fertile soils and good communications supported a lively and socially mixed population, engaged in farming, crafts, and trade. Ecclesiastically it was a chapelry of Dorchester in the Middle Ages, and remained part of the peculiar of Dorchester until 1846. Religious Nonconformity was strong from the 17th century.

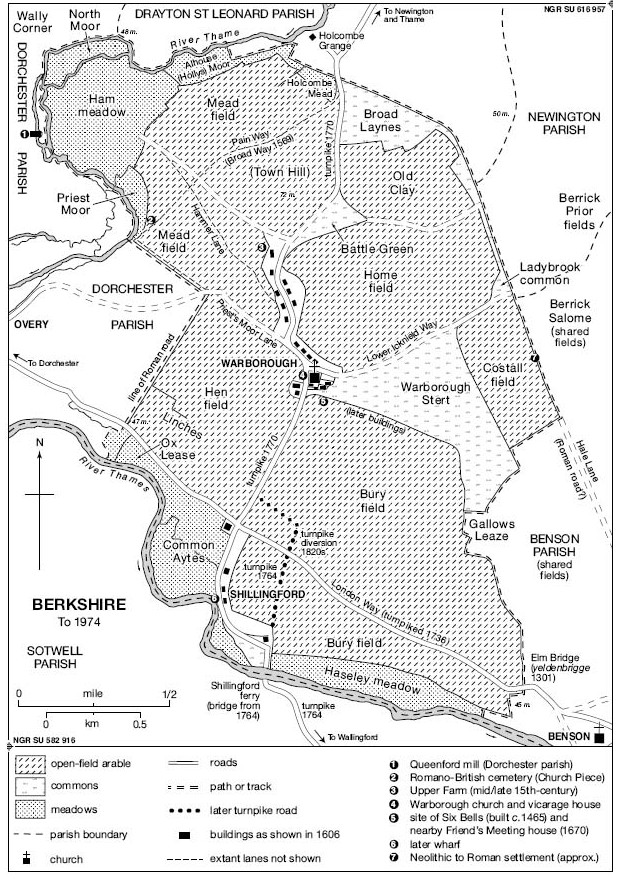

PARISH BOUNDARIES AND LANDSCAPE

Though subsumed within Benson manor by 1086, Warborough was probably already a clearly defined unit: that was certainly so by the 13th century, (fn. 2) and in 1606 its boundaries were mapped. (fn. 3) The parish remained substantially unaltered in 1878 when it comprised 1,697 a., much the same as its modern civil counterpart. (fn. 4)

Several sections of its boundaries (Fig. 108) are of considerable antiquity. The southern and much of the western boundary followed the midstream of the Thames, which formed Berkshire's shire boundary from the 9th century. Further north the river Thame probably formed the boundary between Warborough and Drayton St Leonard by 1086 (when Drayton belonged to the bishop of Lincoln's 90-hide Dorchester estate), although 13 a. of meadow on the Warborough side was shared between several parishes until transferred to Drayton in the 1870s. (fn. 5) Overy, on the Warborough side of the Thame, belonged to Dorchester probably before the 11th century, (fn. 6) and the rectilinear parish boundary near there is early, apparently following two stretches of Roman road. The long, straight boundaries with Newington and Berrick Salome in the north-east and east cut across former commons, likewise following the course of probable Roman roads. (fn. 7) The south-eastern boundary with Benson (dividing fields and commons) was more complex, but was firmly established by the 17th century and probably much earlier. (fn. 8)

The parish lies amidst the gently undulating landscape of the south Oxfordshire clay vale. It is mostly low-lying, with only a modest difference in height between its lowest point by the Thames in the south (at 45 m.) and the top of the only hill, Town Hill, north of Upper Farm (72 m.). (fn. 9) The geology is mainly gravel overlying clay and greensand, with gault clay in the north-east and alluvium by the Thames and the Thame; the soil is part loam and part clay. (fn. 10) The rivers and several small streams provided plentiful water, while culverts and ditches in Warborough village and by Warborough Green assist with drainage.

Most of the parish was organized in large open fields before late inclosure in 1853, but there was also a substantial amount of common pasture and riverside meadow. (fn. 11) The modern parish contains very little woodland (mainly recent plantation on Town Hill), and in the 1840s there was virtually none apart from orchards. (fn. 12) In the late 16th century tenants were required to plant trees to supply building timber and fuel. (fn. 13)

COMMUNICATIONS

Roads, Bridges, and River

The parish has long enjoyed good connections by road and river, including links with Wallingford on the Berkshire side of the Thames two miles south of Shillingford. The main modern routes through the parish are the Oxford–Henley road, which runs west– east, and the Thame–Wallingford road, running north– south through Warborough and Shillingford and over Shillingford bridge. Both roads broadly follow Roman or earlier routes, but with substantial deviations. The Roman west–east route ran north of the modern road, following Green Lane from Overy and Dorchester to pass the southern tip of what is now Warborough village, then crossing through Gallows Leaze. (fn. 14) Its medieval successor followed a more southerly course roughly along the line of the modern road through Shillingford, crossing the yeldenbrigge just over the Benson boundary. (fn. 15) The Thame road briefly follows the line of the Roman road from Fleet Marston (Bucks.) to Dorchester, before turning southwards to Warborough village and on to the Shillingford river crossing. The Roman route ran further west, crossing the Thames at the boundary between Brightwell and Sotwell (Berks.), and continuing to Silchester. Its line forms part of the parish boundary. (fn. 16)

Warborough parish c.1606, based on a contemporary map. (See also Plate 4.)

Shillingford bridge in the late 19th century, looking north-west from the Berkshire to the Oxfordshire bank.

The Roman river crossing was apparently supplanted in the Anglo–Saxon period by a ford at Shillingford ('Sciell(a)'s ford'), (fn. 17) probably in roughly the same area as the modern bridge, although the rivers course and depth have altered over the centuries. The route linking the Shillingford crossing to the Silchester road on the Berkshire side was called the 'bridge way' in the 10th century, suggesting a paved causeway built presumably to improve access to the Alfredian burh at Wallingford. (fn. 18) If so it was superseded in 1203, when a bridge was built over the river from Clapcot in Brightwell-cum-Sotwell (Berks.). (fn. 19) The bridge was last mentioned in 1370, and had probably been abandoned by the early 15th century; (fn. 20) it was replaced by a ferry established by 1354, (fn. 21) which remained in use until the 18th century and was described in 1692 as 'a great boat to waft over carts, coaches, horse and man'. (fn. 22) Both bridge and ferry were approached from the north along the curving southern stretch of Wharf Road, which was apparently cut off by river-bank erosion in the early 19th century. (fn. 23) In the 18th and 19th centuries an additional ferry ran from Keen Edge to the north-west. (fn. 24)

From the 18th centuryboth main roads were improved. The Henley road was turnpiked in 1736, and that from Shillingford to Wallingford and Reading in 1764, followed by its northern stretch to Aylesbury (via Thame) in 1770. (fn. 25) Shillingford ferry was replaced in 1764 by a timber bridge on stone piers (with its own toll gate), (fn. 26) and a new straight stretch of road was constructed to link it to the Henley road. (fn. 27) Old piles and beams dredged up from the river were presumably remains of its medieval predecessor. (fn. 28) The 18th-century bridge was replaced by a stone structure in 1826–7, (fn. 29) and a right-angled road was constructed north-east of Shillingford to bypass the Thame road's narrow southern junction with the Henley road. (fn. 30) The turnpike trusts were abolished in 1873–80, (fn. 31) and in 1890 and 1900 the bridge was repaired at the joint expense of Oxfordshire and Berkshire, the balustrades being renewed in 1929. (fn. 32) A traffic roundabout was constructed at Shillingford in 1977. (fn. 33)

Other early routes included the Lower Icknield Way, a Romanized routeway from Dorchester to Aston Clinton which ran eastwards along the present-day Henfield View and across the north of Warborough Green. (fn. 34) At Ladybrook Copse it crossed the Hale Farm road, a track linking the Henley road with the Fleet Marston road north of Town Hill, and forming a substantial stretch of Warborough's eastern parish boundary. That route survived as a lane until c.1800. (fn. 35) Minor lanes in the north-west were Hammer Lane, Pain Way, and Priests' Moor (later Avery or Overy) Lane, (fn. 36) which joins the Fleet Marston Roman road. Of those, Pain Way and Priests' Moor Lane are now bridleways. All three led to early cemeteries: Priests' Moor and Pain Way to the late Romano-British cemetery on the parish boundary at Church Piece (close to the river Thame), (fn. 37) and Hammer Lane past Church Piece towards the early Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Wally Corner (Dorchester). (fn. 38)

The Thames provided important additional transport. Goods were probably loaded and offloaded at Shillingford from an early period, and by the 18th century it had a wharf. (fn. 39) A replacement, perhaps necessitated by river-bank erosion, (fn. 40) was constructed at parish expense before 1838, when disputes over its management were lampooned in a cartoon and satirical verse by one of the local Tubb family. (fn. 41) The wharf was abandoned in the earlier 20th century. (fn. 42)

Transport and Post Office

In the later 19th and early 20th century daily carrier services to Wallingford were supplemented by services to Oxford and Abingdon on market days. (fn. 43) The parish benefited considerably from its proximity to the main Aylesbury–Reading and Oxford–London roads: numerous stage coaches passed through the parish in the late 18th and early 19th century, stopping at the Bell Inn in Shillingford (demolished in 1969), and probably at other hostelries in the parish, which were mostly located along the main roads. (fn. 44) The Great Western railway, opened in 1839–40, included a station just south of Wallingford, (fn. 45) and from the 1920s frequent daily buses connected Shillingford with Wallingford, Dorchester, Benson, Oxford, and Henley. (fn. 46) A weekly Newington to Wallingford service through Warborough (introduced in the 1940s) was later withdrawn, but in 2010 the Reading–Wallingford–Oxford bus still stopped at Shillingford every thirty minutes on weekdays. (fn. 47)

Mail was delivered from Nettlebed in the early 19th century, (fn. 48) and later from Wallingford. (fn. 49) A sub-post office in Warborough existed by the 1850s until the late 1980s, and was replaced first by a short-lived service in the Nag's Head pub, and later by one in the village hall (St Laurence Hall). (fn. 50) Shillingford had a smaller subpost office from the late 1890s to 1960s. (fn. 51)

POPULATION

Nothing is known about the size of the population before the 13th century. Seventy-seven tenants were mentioned in 1279, of whom 60 held land mainly in Warborough, and 17 in Shillingford; some (including several heads of religious houses) were non-resident, however, and an unknown number of subtenants and landless labourers were excluded. (fn. 52) In 1306 there were 36 taxpayers, 24 in Warborough and 12 in Shillingford. (fn. 53) The parish's agrarian economy seems to have remained fairly vibrant in the late Middle Ages, and population decline after the Black Death may have been limited, thanks partly to inward migration. (fn. 54) In 1377 poll tax was levied on 152 individuals aged over 14 (one of the highest numbers in rural south Oxfordshire), (fn. 55) and c.1480 Warborough had the most men fit for military service in Ewelme hundred. (fn. 56) The 1543 lay subsidy was paid by 31 heads of household. (fn. 57)

The population seems to have grown steadily to 1640 and beyond. (fn. 58) Baptisms consistently outstripped burials, and many families had five or more children, who mostly survived into adulthood. Nevertheless there was significant out-migration, while occasional periods of high mortality included the years 1643–4, when disease was spread by Civil War troop movements. The estimated adult population in 1676 was c.230, (fn. 59) and by 1761 the total population was 450 (322 in Warborough and 128 in Shillingford), rising to 526 by 1781. (fn. 60) Thereafter numbers grew from 535 in 1801 to 737 in 1841, and by 1851 Warborough contained 115 households, and Shillingford 44. (fn. 61) The 19th-century population peaked at 764 in 1861, falling to 658 by 1891 and to 585 ten years later, as agricultural depression prompted further out-migration. The first half of the 20th century saw little change, but thereafter new house-building fuelled a substantial rise from 700 in 1951 to 845 by 1971, and to 1,012 by 1981. In 2011 there were 987 inhabitants and 433 houses. (fn. 62)

SETTLEMENT

Prehistoric and Roman Settlement

The Dorchester area, at a nodal point for communications in the Upper Thames, was an important centre of Prehistoric activity, (fn. 63) and the parish contains numerous Prehistoric remains of which some are visible as crop-marks. A large multi-phase complex west of Warborough village, straddling the Dorchester boundary, (fn. 64) includes a probable Neolithic mortuary enclosure, (fn. 65) while a smaller enclosure east of Wharf Road in Shillingford may be of the same period. (fn. 66) Two long barrows used for communal burial are located towards the parish's south-east corner, (fn. 67) between two pairs of linear ditches, (fn. 68) and a third lies in the far north. (fn. 69) Excavation near the Berrick Salome boundary, east of Warborough Green, yielded direct evidence of small-scale late Neolithic and early Bronze-Age activity. (fn. 70) A series of ring ditches in and around the big mortuary enclosure seems to be remains of round barrows used for high-status Bronze-Age burials, (fn. 71) and a ring ditch, hut circle and enclosures are associated with the long barrow in the north of the parish. (fn. 72)

Later settlement in the Warborough area was presumably encouraged by proto-urban activity at Dorchester in the late Iron Age, and by the subsequent development of the Roman town. (fn. 73) Occupation at the site near the Berrick boundary intensified in the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age and continued uninterrupted through the Roman period, when an enclosed Romano-British settlement with a corn drier succeeded the open areas of Iron-Age settlement. (fn. 74) Further west there may have been Iron-Age settlement near Shillingford, (fn. 75) and some enclosures in the Dorchester-Warborough complex may also be Iron-Age, (fn. 76) while residual Iron-Age pottery was found at Church Piece. (fn. 77) Two further probable Romano-British settlements have recently been identified north of the Dorchester-Henley road, one (in the south-east) apparently an extensive settlement with surrounding enclosed fields, (fn. 78) and the other (west of the Thame road) possibly a smaller settlement or villa farmstead, approached along a trackway. (fn. 79) A large cemetery at Church Piece, with associated enclosures and buildings possibly including a villa, presumably served the inhabitants of Dorchester a kilometre west over the Thame. (fn. 80) The burials were east-west aligned and without grave goods, while most of the pottery is 4th-century. (fn. 81)

Anglo-Saxon Settlement

Little is known about early post-Roman settlement, though in the Dorchester area generally there was an overlap between sub-Roman and early Anglo-Saxon groups and cultures. Nevertheless, the mainly 4th-century Romano-British type cemetery at nearby Queenford Mill (Dorchester) appears to have been succeeded by an Anglo-Saxon-style cemetery at Wally Corner in the 5 th and 6th centuries, (fn. 82) and sunken-featured buildings tentatively identified at Church Piece may also date from the later period. (fn. 83) The extent and location of early Anglo-Saxon activity is difficult to determine, but a handmade biconical urn was found close to Hammer Lane, not far from Church Piece. (fn. 84)

Place-name evidence from the mid-to-late Anglo-Saxon period points to a well-organized and inhabited landscape, latterly forming part of the Benson royal estate. (fn. 85) The name Warborough ('watch hill') suggests a settlement near the barrow-shaped Town Hill, (fn. 86) possibly assigned a special role as a look-out point overseeing the neighbouring royal centre at Benson. Iron weapons found in the 19th century at Battle Green, near Town Hill, may have been Anglo-Saxon. (fn. 87) Shillingford was probably a subsidiary focus of settlement, limited by its rather marshy terrain. The creation of a burh at Wallingford at the end of the 9th century presumably encouraged the linear, mainly north–south, roadside settlement which later characterized both places. (fn. 88)

Development from the Middle Ages

By the late 11th century most farmsteads were probably spread along the Thame–Wallingford road. In the mid 12th century there was apparently a homestead at 'the Gare', along what was then described as the road from Warborough to Holcombe, (fn. 89) and a late 15th-century hall house (Upper Farm) survives by Little Green (next to Battle Green) at the villages northern end. (fn. 90) Several other late-medieval and 16th-century houses line the main road and the western edges of Warborough Green, at whose apex Warborough church was built by c.1200, probably encouraging further development there. (fn. 91) Houses in Shillingford were perhaps more loosely focused on the junction of the Wallingford and Henley roads, stretching southwards towards the river crossing.

A map of 1606 (fn. 92) shows c.14 houses between Battle Green (to the north) and Warborough church, together with the vicarage house, and a dozen mainly small houses at Warborough Greens western end, ranged around the island of land which included the churchyard. Further west across the road stood the parsonage barns and a large house (now demolished) belonging to St John's College, leased by Mr Deane. (fn. 93) Shillingford was represented by one large house south-west of the cross-roads, three others along the lane to the wharf, and an isolated building inland from the ferry, presumably the ferryman's house.

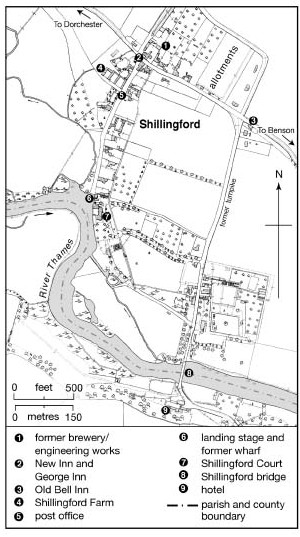

The density of settlement increased between the 17th and 19th century, (fn. 94) and by the mid-to-late 19th century Warborough was a polyfocal settlement stretching from the edge of Town Hill to a house called Oatlands, almost three-quarters of a mile to the south along the Thame road. In the north was a cluster of houses around Little Green (just south of Battle Green), but the densest concentration lay a quarter of a mile to the south, with one group of houses sited west of the main road, another around the church, and two more stretching eastwards along both sides of Warborough Green. Further south again were some more roadside houses and a malthouse and coal yard, the village's main farmhouses lying north of the church. Shillingford was a smaller settlement ranged around the junction of the Thame–Wallingford and Oxford–Henley roads, its two main clusters of houses stretching eastwards along the north side of the Oxford–Henley road (where a brewery was built in mid-century), and along the lane leading to the Thames-side wharf. A few houses stood on the turnpike road leading south-eastwards to Shillingford bridge. (fn. 95)

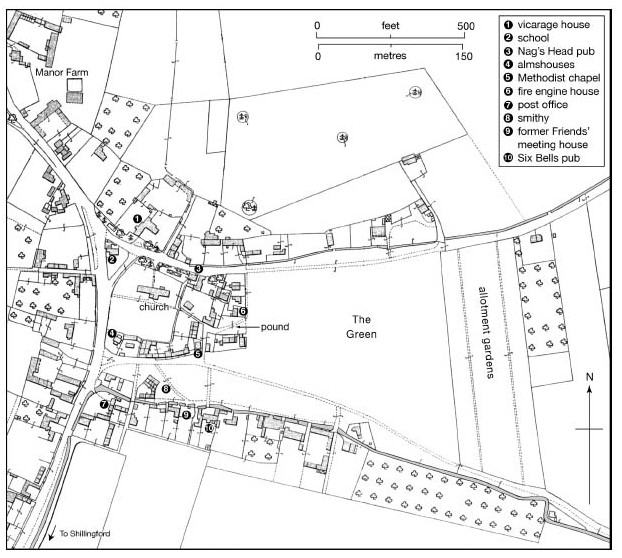

Warborough green in 1910, showing key buildings. (Compare Plate 4.)

Expansion during the 20th century linked both settlements along the west side of the Thame road. Warboroughs main growth came through council-house building on part of the former Hen field in the west, chiefly in the 1950S–60S, while in the 1960s– 70s a few other houses appeared further south along the Warborough–Shillingford road. (fn. 96) Shillingford saw intensive, mainly private, housing development north of the Henley road, with some additional large houses built on extensive plots between Wharf Road and the road to Shillingford bridge. (fn. 97) In all c.90 houses and flats (including 29 council properties) were built in the parish between 1969 and 1974, mainly in Shillingford; (fn. 98) later building was restricted both by local opposition, and by the establishment of a conservation area in 1978. (fn. 99)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Warborough is an attractive village which retains many 16th- to 18th-century houses along the Thame road and around the green. (fn. 100) The older houses are timber-framed, with infill of clunch rubble with brick dressings, perhaps replacing earlier wattle and daub. Many are rendered. Old plain-tile roofs are widespread, but some houses are thatched, including the Six Bells on the south side of the green. (fn. 101) A number of houses lie gable-end to the street, perhaps reflecting the development of house plots on former open-field land. Despite some 20th-century infill along the main road in the south, the main modern developments (Henfield View and Sinodun View) are tucked away behind the mid 18th-century Cricketers' Arms. (fn. 102) Shillingford, which includes many later 20th-century houses, gives a rather drab appearance from the main road, though Wharf Road retains some fine 18th-century buildings.

Shillingford in 1932.

The church apart, surviving medieval buildings include Upper Farm (in the north), 119 Thame Road, and the Six Bells (on the green). (fn. 103) Upper Farm is a high-quality four-bay house with a two-bay open hall and partial upper storeys, now dendro-dated to 1455–92. A brick chimney stack was inserted and the hall ceiled c.1600, and the timber-framed structure was encased in clunch when the house was enlarged in 1791, probably by the Saunders family. The house was gutted and converted to a barn in the earlier 20th century, but returned to residential use in the 1980s. (fn. 104) Amongst several 16th-century houses is the substantial, timber-framed Western House on the east side of the Thame road, now divided in two, which has been dendro-dated to 1574/5. (fn. 105)

In the 17th century lobby-entry plans became common, featuring in both new-builds and, through insertion of chimney stacks, in older houses such as 119 Thame Road. Surviving inventories suggest that most late 16th- and 17th-century houses included a hall and one or more chambers, while larger ones had additional parlours, kitchens and butteries. (fn. 106) Some also had separate malt houses, where brewing vessels, troughs, and barrels were kept. (fn. 107) Dwelling space was widely remodelled and extended in the 18th century, the period when many of the villages other houses were built. A number of 17th- to early 19th-century barns survive, including clunch and weather-boarded examples at Court Farm. (fn. 108) Twentieth-century buildings include a terrace of four whitewashed modernist houses south-west of the church, built as farm labourers' accommodation for St John's College, Oxford, in 1952, to designs by Lionel Brett (later Lord Esher). (fn. 109)

The area around the spacious and tree-fringed Warborough Green forms the centre-piece of the village. On the south side is a large farmhouse formerly called Beech House, now renamed 'The Manor', with a sizeable thatched barn adjacent. The house is substantially late 17th-century, but was altered in the 18th and 19th centuries; it appears to have been built by the Herbert (or Harford) family, some of whom are commemorated by grave slabs on the floor of the church tower. (fn. 110) Other houses around the Green were originally modest, and until their demolition in 1849 included twelve cramped cottages by the churchyard, known as 'The College'. (fn. 111) Two nearby almshouses were built by the perpetual curate Herbert White in the same year. (fn. 112)

Shillingford includes four substantial early-to-mid 18th-century houses: Shillingford Farmhouse, Riverside House, and The Loans (all on Wharf Road), and Shillingford Greenacre on Warborough Road. (fn. 113) All have symmetrical five-bay fronts and red brick dressings, most with flared headers. They are set amongst smaller houses of 18th-century and later date, and some outbuildings (including a granary and a coach house) have been converted to domestic use. (fn. 114) Shillingford Court, by the river, is a large late 19th-century house built by the wealthy tailor Frederick Mortimer, approached along a tree-lined drive off the Wallingford road, the latter now flanked by late 20th-century houses. (fn. 115) On the main Henley road a former local authority children's and (later) old peoples home called Caldicott House was converted into private housing in the 1970s. (fn. 116)

The box-framed 17th-century cross wing of 119 Thame Road (Ash Tree Cottage), adjoining a lower 15th-century hall range (left).

The Manor (Beech House) at Warborough Green, with its adjacent barn.

MANORS AND ESTATES

In 1086 Warborough formed part of the extensive royal manor of Benson. (fn. 117) The Crown retained the largest landholding in Warborough until the early 17th century, but granted land and rents to others including Godstow nunnery and Dorchester abbey. Their estates were initially regarded as still part of Benson, but by the end of the Middle Ages were treated as separate manors. As elsewhere on the Benson estate there was enduring ambiguity over rights of lordship and the ownership of particular areas of land, exacerbated by the complexity of local tenures and the number of small freeholdings.

After the Dissolution the Godstow and Dorchester estates were acquired by Sir Thomas White (d. 1567), who transferred them to his new foundation of St Johns College, Oxford. Protracted challenges to its title were eventually overcome, and in 1844 the college owned an estate of over 500 a., which it enlarged before selling up in the late 20th century. Lords of Benson manor retained a much diminished Warborough estate until the 1930s, when it was sold to St Johns.

MEDIEVAL ESTATES

The first large alienation of royal land in Warborough was an estate in Shillingford, given to the recently dedicated Benedictine nunnery of Godstow in the early 12th century. By separate grants King Stephen and Matilda gave the nuns 2½ hides and ½ yardland in Shillingford c.1136–41, comprising land which had previously been leased to Ralph the scribe for £2 12s. 6d. a year. In 1142–4 Matilda granted the nuns lordship (soke) and exemption from the hundred court, (fn. 118) while Walter, archdeacon of Oxford c.1150, gave additional land inherited from his aunt (amita) Brityna. (fn. 119) Part of the nunnery's estate was withheld by Geoffrey de Ivoi (d. 1178) as lessee of Benson manor, but was restored c.1160, (fn. 120) and later the nuns were said to hold the 'vill' of Shillingford. (fn. 121) In 1279 their estate was described as two carucates (c.240 a.) of former royal demesne and a few acres of other land, (fn. 122) but in reality it seems to have been regarded as a separate manor. Certainly in the late Middle Ages the nuns had their own court leet, (fn. 123) and the abbess paid a nominal quitrent to Benson manor. (fn. 124)

A second grant (of rent rather than land) caused considerable problems. In 1278 Edmund, earl of Cornwall, refounded the chapel of St Nicholas in Wallingford castle as a collegiate church, and the same year endowed it with rents in Warborough and Shillingford worth £40 a year, half of his total fee farm rent from Benson manor. (fn. 125) Part of the sum (£188s.) was paid by the tenants, and the rest by 18 lessees of the demesne. The rent seems to have represented the whole of Edmunds revenue from his Warborough estate, which in 1279 included 36 yardlands and over 84 a. of other land in the parish, and probably also the whole of Benson manors demesne arable there (184 a.). (fn. 126) In 1316 it was claimed that Benson with Warborough and Shillingford still belonged to the Crown, (fn. 127) but an inquisition of 1438 stated that the land and tenements yielding the £40 rent were completely separated from Benson. (fn. 128)

The abbot of Dorchester (already the owner of Warboroughs tithes and glebe) (fn. 129) headed the demesne lessees, and in 1276 Edmund of Cornwall gave the abbey another 4 yardlands in Warborough, (fn. 130) followed by additional small grants from other local landowners. (fn. 131) In 1535 the abbey received £12 17s. ½d. rent from its Warborough tenants, and paid £8 12s. 5½d. to Wallingford college and 18d. quitrent to Benson. (fn. 132)

LANDHOLDING SINCE THE DISSOLUTION

In 1536–9 Dorchester abbey and Godstow nunnery were dissolved and their properties taken into royal hands. (fn. 133) The manors of Warborough (190 a.) and Shillingford (324 a.) were mortgaged in 1544 to a syndicate of London merchants, headed by the haberdashers Thomas Blanke and Richard Allen; (fn. 134) the mortgage was not discharged, and ownership passed to the syndicate, subject to the £40 rent charge to the dean and college of Wallingford. That continued until the college was dissolved in 1548, after which a quitrent of £31 7s. 7d. to the Crown took its place. (fn. 135) Blanke bought out his partners, and in 1556 sold the manors to Sir Thomas White, a London alderman and merchant tailor, for £400. White then gave them to St Johns College. (fn. 136)

The colleges title to the Warborough estate and its claim to manorial rights were soon questioned. Blanke had already faced challenges from his tenants, and after the sale to St Johns the deputy steward of Benson manor warned them not to appear at the colleges Warborough court. (fn. 137) The dispute focused on former royal demesne called Bury lands, and in 1587 the college paid over £700 to acquire 12½ yardlands in Bury Field (found to have been 'concealed' from the Crown apparently by Blanke and Allen), and to extinguish the quitrent. The lands were to be held in free socage of the manor of East Greenwich. (fn. 138)

Subsequently William Tipper, a Londoner who had obtained a commission to reveal 'her Majesty's titles concealed or detained', discovered a technical defect in the conveyance to Blanke and his fellow merchants, and the queen dispossessed the college of both Warborough and Shillingford manors. (fn. 139) Tipper obtained a lease of lands recovered, before the manors were granted to him and his partner Robert Dawe in 1592. (fn. 140) The college bought them back in 1598–1601, (fn. 141) and, since the tenants' titles were invalidated by the new grant, was able to recover £50 for the renewal of leases for 25 yardlands. (fn. 142) In 1606 the college's title to certain freehold land in Warborough was said to be unknown, (fn. 143) but there were no further legal actions, and the college held courts baron for Warborough and Shillingford until the mid 19th century. (fn. 144) In 1836 its land lay mainly in open-field strips spread across the parish, with some concentration in Home, Middle and Lower Bury fields in the south, while its two chief properties were Upper farm and Shillingford farm. (fn. 145) In 1844 the estate totalled 566 a., (fn. 146) expanded by the purchase of 30 a. of common land and several smallholdings in the early 1850s, and of White's farm (c.50 a.) near Warborough Green in 1872. (fn. 147) By 1914 its estate exceeded 820 acres. (fn. 148)

A large part of the parish remained at least nominally Crown property in 1606, when a survey of Benson manor listed 51 holdings wholly or partly in Warborough parish, amounting to 1,048 a. and including freeholdings of 305 acres. (fn. 149) The Crown also retained Shillingford ferry and its fishery. (fn. 150) The boundaries of Benson manor could not be fully determined because its lands were so intermixed with other estates, however, and most tenants paid the bulk of their rents to St John's. (fn. 151) When the Crown sold Benson manor in 1628 only a limited amount of land in Warborough seems to have been included, (fn. 152) and in 1844 the Stapletons (as lords of Benson) owned only 165 a. there, the bulk of it comprising Court farm. (fn. 153) Before 1910 they added Manor farm (251 a., including 233 a. within the parish), (fn. 154) which was sold to St John's in 1937. (fn. 155)

The college sold most of its Warborough estate piecemeal in the 1970S–80S. Upper farm and other land (524 a.) was sold to J.P.D. Heyward in the early 1970s, (fn. 156) and in 1987 to the chairman of Midland Pig Producers Ltd, who retained it in 2010. (fn. 157) Shillingford farm (912 a., including over 700 a. in Warborough) was sold to Amey Roadstone Construction, which sold it to the tenant B.M. Cook in 1978, retaining gravel rights for sixty years. The Cooks added 120 a. in Berrick Salome in 1982, and retained the farm in 2010. (fn. 158) St John's sold the lordship of Warborough manor to C.S. Windebank of Manor Farm for £450 in 1972, (fn. 159) but retained nominal lordship of Shillingford manor. (fn. 160)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Warborough occupies a fertile part of the south Oxfordshire clay vale. The parish's economy was long based on mixed farming, supplemented by a lively trade and craft sector; there were no major resident landowners, and from the Middle Ages the chief cultivators were the customary tenants, leaseholders and small freeholders, farming scattered open-field strips until inclosure in the early 1850s. Thereafter holdings were consolidated, and by the mid to late 20th century two principal farms covered over half the parish. Farmers benefited from access to London by river and road, and from local markets including Wallingford, Abingdon, Henley, and Thame. The parish also had several inns and shops, and in the 19th century there was a brewery in Shillingford.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 108)

In the early 19th century the two settlements were surrounded by shared open fields, (fn. 161) with inclosures mostly restricted to closes and orchards (some of them of medieval origin) on the settlement fringes. (fn. 162) Meadows were located on the low-lying river floodplains, and commons were ranged around Home field in the north-east. Woodland was largely confined to trees in hedgerows.

An open-field system was functioning by the 12th century, (fn. 163) and may have been established considerably earlier. Three fields were mentioned in 1206, (fn. 164) and Shillingford, Warborough, Bury and Hem (or Hen) fields were named before 1350. (fn. 165) Bury field, described in 1336 as the Bury field of Benson and Warborough, (fn. 166) was perhaps created or reorganized when the Benson demesne was divided among local farmers in the late 13th century. Shillingford field seems to have included land in Hen field as well as Bury field, (fn. 167) while the nucleus of Warborough field appears to have been the later Home and Mead fields. Outlying fields may have been at least partly created through the ploughing up of waste, which was ongoing in the late 13th century. (fn. 168) Possible examples are Costall field (east of the Marsh), and Old Clay or Clay field, which cut into Broad Lanes common north of Home field. (fn. 169)

An estate map of 1606 shows six fields. (fn. 170) In the south was the large Bury field (east of the Thame road), said in the later 16th century to comprise 24 yardlands or c.576 a. of arable and 80 a. of meadow; (fn. 171) the acres, however, were allegedly of 'small measure', some no more than half statute acres. (fn. 172) West of the Thame road was the smaller Hen field, and further north were Home field, Mead field, and the small Costall and Old Clay fields. Most fields were by this time subdivided, (fn. 173) among them Bury field (which was split into three), and Home field (which included Chicks Hill field). (fn. 174) Hen field's southern part near the river Thame was called Linches, an area which had apparently been pasture c.1200. (fn. 175) A survey of 1698 gave a total of 72½ yardlands in the parish. (fn. 176)

Permanent grassland was fairly extensive, much of it low-lying land affected by flooding. The chief meadows were Haseley mead (36 a.), Common eyot (20 a.), and Farm mead (16 a.) by the Thames in the south, with North moor (17 a.), West moor (16 a.), and Hollys moor (13 a.) lying by the Thame in the north. Most meadowland was either commonable at particular times of the year (like Common eyot), or divided into lots attached to holdings in the open fields (like Haseley mead, attached to Bury field). (fn. 177) Commons, which totalled 146 a., spread eastwards from Warborough Green and Battle Green, (fn. 178) whose funnel-like shapes may have facilitated livestock movement. Intercommoning arrangements with Benson, Berrick Salome, Drayton, and Newington suggest that the commons once formed part of more extensive pastures shared between neighbouring settlements, (fn. 179) although the right of Warborough tenants to pasturage in the bishop of Lincoln's fee of Overy was contested in the late Middle Ages. (fn. 180)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

From the 11th to the late 13th century much land was managed as part of Benson manor, and included both demesne and tenant holdings. Benson's demesne arable was apparently concentrated in Bury field in the south of the parish, and in the 12th and early 13th century was sometimes farmed directly and sometimes leased. (fn. 181) When taken back in hand in 1178–9 it was sown with cereal crops and re-stocked with plough beasts, cows, sheep, and pigs. (fn. 182) The substantial piece of demesne granted to Godstow nunnery in the 1140s had previously been leased, and presumably the nunnery continued the practice. (fn. 183)

Little is known about tenant farming until 1279, when over 70 tenants held 36¼ yardlands and other land in Warborough and Shillingford. (fn. 184) In Warborough the abbot of Dorchester and 21 sokemen held 14 yardlands for 5s. assize rent and 2s. hidage per yardland, owing light mowing and carriage services, tallage, and suit of court. A group of 22 customary tenants (of whom several also held land as sokemen) held 11 yardlands for the same rent but slightly heavier services. A further 3¾ yardlands and 78 a. had been sublet, partly to a few free tenants, and were held by charter and money rents. In Shillingford 15 customary tenants held 6½ yardlands for similar services to those owed in Warborough, while the abbess of Godstow held 2 carucates of former demesne and a few odd acres, and the abbot of Osney a yardland of demesne. (fn. 185)

The grant of £40 rent to Wallingford castle chapel in 1278 led to considerable agricultural reorganisation. The demesne was leased to a group of 18 tenants headed by the abbot of Dorchester for £21 12s. a year, each lessee paying 24s. This was intended as a perpetual grant, and had more fundamental consequences than previous leases, notably the commutation of labour services for increased money rents. Some 33¼ yardlands were accordingly let on new terms: 6½ to eight men for £3 a year (10s. each), 15½ to 28 tenants in two separate groups for £9 6s. (12s. each), and the rest for varying amounts, along with smaller pieces of land and meadow. (fn. 186)

By the 13th century and probably earlier Warborough was a considerably larger and wealthier vill than Shillingford. (fn. 187) In 1306 there were twice as many taxpayers in Warborough as in Shillingford, (fn. 188) and in 1334 Warborough paid the substantial sum of £8 7s. 2d. in tax, compared with Shillingford's £1 17s. 8d. (fn. 189) Larger tenant holdings were also concentrated in Warborough, although individual farms varied in size across the parish, and many yardlands were subdivided, shared, or sublet. In 1279 the abbot of Dorchester and a local tenant each held two yardlands, while two tenants held 1½ and 1¼ yardlands respectively. Eight others (including the abbot of Osney) held whole yardlands, three had 5/6 yardland, and three had ¾ yardland. Another 28 tenants had a standard ½ yardland, though six held only ⅓, and three only ¼ yardlands. (fn. 190) The leading tenants' holdings were increased by the subsequent demesne lease.

The Black Death and its aftermath must have affected Warborough and Shillingford, although the high value of Warborough's tithes in the early 16th century suggests that dislocation was less severe than in Benson. (fn. 191) The parish retained a sizeable population of customary and other tenants, (fn. 192) who by and large continued to pay their rents. The £40 rent charge to Wallingford castle chapel was apparently still demanded in full, (fn. 193) and in 1443–4 Dorchester abbey's rent collector, Richard Osgood, reported fairly modest arrears of 19s. 6d. in Warborough, out of £8 13s. 5d. due. (fn. 194)

Medieval tenants presumably pursued the mixed farming evident on the demesne. Some leased additional pieces of meadow to provide for livestock, and pigs were kept. (fn. 195) From the later 14th century there may have been increased emphasis on grazing, but much cereal cultivation continued, (fn. 196) and there is no indication of large-scale inclosure or conversion of arable to pasture. Agricultural priorities on Godstow abbey's Shillingford manor may be reflected by the fact that in 1535 its lessee Ralph Randolph owed 16 qr of wheat and 16 qr of barley as his annual rent. (fn. 197) The closest market for surplus produce was Wallingford, though from the later 13th century Henley probably became increasingly important. (fn. 198)

Little is known about agricultural management, the main decision-making forums being presumably the Benson and Shillingford manor courts. (fn. 199) Yardlands lay intermixed in the open fields by the later Middle Ages, and tenants' animals generally shared the same pastures, (fn. 200) tenants of Godstow abbey and the lordship of Warborough reportedly sharing common rights across the parish from Lammas (1 August) to the Annunciation (25 March) in the 1470s. (fn. 201) Bury field was separately organized, however. (fn. 202)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

Farming in the post-medieval period continued within a customary open-field system, (fn. 203) with little sign of the piecemeal inclosure or engrossing which occurred in neighbouring Benson and Dorchester. (fn. 204) Most land was copyhold, and the chief landlords (St John's College, Oxford, and the lords of Benson manor) consequently received only a fraction of their estates' real value: even in the late 18th century very little land was leased at rack rent. (fn. 205) Nevertheless there were some freeholds and one or two leaseholds, and subletting seems to have been common, while copyholders themselves benefited from secure tenure and fixed rents. London's growing population continued to provide a large market for cereals, while towns like Abingdon and Henley created considerable demand for barley to supply their maltsters. (fn. 206)

In the late 1540s and early 1550s rents from the former Dorchester and Godstow abbey estates, then in Crown hands, amounted to just over £52. (fn. 207) Some rents were paid in arrears, as in other periods of disruption or weak supervision such as the early 1640s. (fn. 208) The largest single holding was Shillingford manor or farm, formerly owned by Godstow abbey, which like the Dorchester lands passed to St John's College; (fn. 209) in 1606 it comprised ten yardlands in Costall field, Chicks Hill, Old Clay, Town Hill, Hen field, and Shillingford field. (fn. 210) In 1535 the abbey's lessee paid a corn rent worth £6 8s. for the Shilllingford demesne, and tenants-at-will a further £2 12s. 8d., while in 1537 the entire estate was let for £9 0s. 8d. (fn. 211) By the late 1550s the farm was held by Sir Thomas White's nephews William and Edward Bridgeman, passing to their sister Amy, who married William Leech. Sir Michael Moleyns of nearby Clapcot (Berks.) bought the lease in 1602, paying St John's a £24 fine, (fn. 212) and though Amy later claimed precedence as Founder's kin, a settlement in favour of Moleyns's son was reached in 1620. (fn. 213) Presumably the farm was sublet.

Other late 16th-century holdings were mainly whole and part yardlands, held by two-or three-life copyholders and free tenants under St John's College and Benson manor. The holdings fell into two main groups: first, free tenancies and 'base-tenure' copyholds in fields outside Bury field (known collectively as 'home land' or 'home field'), (fn. 214) and second, copyholds in Bury field itself. The free tenants held their land for small quitrents, owing suit of court and paying half their rent as relief. (fn. 215) Base-tenure copyholds (which passed by custom to the youngest son) usually owed 12s. rent per yardland, along with suit of court, heriot, and a quarter of the rent as relief, (fn. 216) while yardlands in Bury field were held at will or by copyhold for 24s. 6d. a year, owing suit of court, entry fines, and heriot. (fn. 217) Some tenants in the later 16th century unsuccessfully claimed their Bury field land as freehold. (fn. 218)

A survey of Benson manor in 1606 (which excluded Shillingford farm and most of Bury field) listed 45 holdings situated wholly or mainly in Warborough parish, and held by 40 tenants. (fn. 219) In all, those comprised 20 copyholds held in base tenure (558 a.), 18 free holdings (305 a.), and seven copyholds of Bury field land granted at Benson court between 1593 and 1602 (185 a., including 162 a. in Warborough parish). Over all Warborough had a much higher proportion of copyhold land (60 per cent) than Benson itself, where over 80 per cent of land was freehold. (fn. 220) The largest single holding (196½ a. of freehold and base-tenure land) was that of Richard Spyer, who held additional land in Benson. (fn. 221) Other tenants with farms of over 40 a. were John Phelp or Janes (90¾ a., mainly base tenure), John Gammon (78 a., base tenure), William Hobbes (69¼ a., mainly freehold), William Bartlett (49½ a., base tenure), John Barrett (47½ a., copyhold), and William Warner (46 a., copyhold). The average tenant farm was 25½ a., and 18 individuals had holdings under 20 acres.

Some families retained their copyholds over long periods, (fn. 222) and few holdings seem to have been subdivided. (fn. 223) Subletting, by contrast, seems to have been common, the number of outsiders holding land increasing after the Civil War. (fn. 224) Entry fines for copyholds and leaseholds on the St John's College estate rose substantially after c.1740, when fines of £50–£200 became common, (fn. 225) while rents per acre of arable were estimated in 1751 at c.18s. (fn. 226) Some were lower, however, a holding of 26 a. being sublet in 1772 for only £16 10s.4 By 1785 some 12–15 larger occupiers of land were recorded in the parish as a whole, alongside numerous small ones. (fn. 227)

Farming remained mixed, with an emphasis on cereals. (fn. 228) Wheat and barley were the most valuable crops, much of the barley being malted, but rye, pulses, peas, and hemp were also grown. (fn. 229) In the 16th and 17th century most tenants had only a few animals, with cows kept in small numbers, and not many farmers having a hundred or more sheep. Nevertheless grazing was carefully regulated, and in the late 18th century fines were exacted for exceeding the 'ancient stint' of 30 sheep per yardland. (fn. 230) Many tenants had gardens and orchards, and some kept bees as well as the usual pigs and hens.9 Cheese-making was common.

Agricultural affairs were still at least partly managed by the Benson and Shillingford manor courts in the 16th and 17th centuries, (fn. 231) but thereafter decisions were taken mainly in the vestry. In 1698 a three-course rotation was being followed, leaving a third of land fallow each year; (fn. 232) nevertheless substantial areas of fallow were sown (or 'hitched') to improve fertility, especially with beans and clover. (fn. 233) Cropping practices presumably reflected soil variations across the parish. Bury field was said in 1590 to be light ground, with a bushel and a peck sufficient to sow every acre. (fn. 234) That and other land in the south was well suited to growing barley, while the heavier ground further north was good for corn and beans, despite needing draining in places. (fn. 235)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

In the first half of the 19th century Warborough supported an open-field farming community dominated by an oligarchy of substantial farmers. Inclosure was delayed by the continuing viability of open-field farming in a fertile area with good market links, the strength of customary tenure, the complexity of local landholding, and the lack of major resident landown ers. (fn. 236) Agricultural affairs continued to be managed by the vestry, (fn. 237) with occupation of open-field holdings determined by a parish terrier drawn up in 1819. (fn. 238) By 1837 farming was organized around a four-course system, with equal areas of 285 a. under (1) wheat, (2) barley, (3) pulses, and (4) clover, vetches, or turnips. Meadow (186 a.) provided hay, and commons (c.200 a.) were grazed by cows and sheep. (fn. 239) Wallingford probably remained the most important local market, though cattle, corn, wool and other produce was traded also in the parish, in nearby Dorchester and Abingdon, and at local village fairs. (fn. 240) Even so, falling tithe values in the 1820s–30s probably partly reflected low grain prices. (fn. 241)

In 1844 twelve farmers occupied three quarters of the parish (1,255 a.), (fn. 242) the largest holding being Harriet Beisley's (195 a.), which belonged mainly to the Stapletons and was later called Manor farm. (fn. 243) John Forty's 178-a. Shillingford farm included some consolidated blocks of land in Hen field, Costall field, and elsewhere. The other main farms were those of Joseph Ashby (139 a.), Richard Saunders (131 a.), Henry Saunders (the 117-a. Upper farm), Richard Swell (105 a., later called Court farm), John Beisley (the 88-a. Violets farm), Daniel White (81 a.), John Smith the younger (66 a.), Richard Hyatt (60 a.), Benjamin Tubb (49 a.), and William Watters (46 a.). Two farms (Richard Saunders's and John Smith's) were mainly owner-occupied, and a few were either predominantly copyhold or a mixture of freehold, copyhold, and leasehold. The majority were leased, however, some from freeholders, but most from tenants (and especially copyholders) of St John's College. Shillingford farm was sublet by its leaseholder James Fuller, who took it for twenty years in 1838 for a £320 fine. (fn. 244)

Inclosure, carried out in 1848–53 under the general inclosure Act of 1845, was almost certainly promoted by St John's and supported by other landowners and major occupiers, (fn. 245) and allowed proprietors to buy land as well as consolidating the position of the dozen leading farmers. By 1851 twelve farmers controlled 1,306 a. and employed 88 labourers, (fn. 246) and concentration of land in fewer hands continued gradually thereafter. By 1871 Henry Ashby was farming 320 a., Henry Beisley 277 a., and James Shrubb 200 acres, (fn. 247) and by 1901 there were eight farmers and two farm bailiffs. (fn. 248)

St John's, like many Oxford colleges, continued to issue 'beneficial leases' until the mid 19th century, (fn. 249) its tenants paying large entry fines (fn. 250) and nominal rents which sometimes still included a proportion of corn rent. (fn. 251) The college finally moved to rack rents from the 1850s, (fn. 252) much later than subletting tenants and smaller landowners. (fn. 253) During the late 19th-century agricultural recession, rents were reduced and some farmers failed, but problems were partly mitigated by the high quality of much of the land and the proximity of local market towns. (fn. 254) The parish saw much less of a switch to pasture and dairying than many nearby places, and 'old-fashioned' sheep-corn farming continued. (fn. 255)

By the 1910s there were four main farms, (fn. 256) of which Shillingford farm (c.544 a. in Warborough and Dorchester) had been held from St John's by Frank Shrubb since his father's death in 1886. Upper farm (308 a.) was leased from the college by L.B. Saunders, while Manor farm (262 a.) and Court farm (139 a.) were held of the Stapletons. In 1917 rent for Shillingford farm was increased from 25s. to 30s. per acre, but Shrubb struggled in the less favourable conditions of the 1920s and was bankrupted in 1930. Upper and some other farms similarly saw a rapid turnover of tenants during the 1920s, and rents had to be reduced. (fn. 257) Reduction of farming employment in the late 19th and early 20th century was partly offset by domestic and gardening work, as the number of private residents increased. (fn. 258)

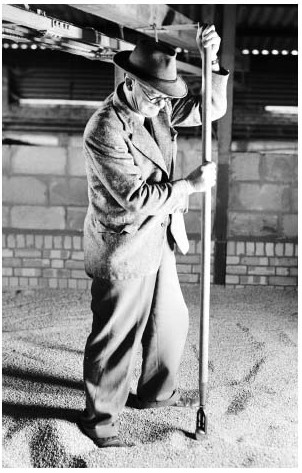

J.R. Warburton of Shillingford Farm inspecting grain samples, 1954.

In 1931 Shillingford farm (then 451 a.) was leased to J.R. ('Dick') Warburton, an agricultural engineer who remained until his death in 1959. (fn. 259) During his tenure the farm was enlarged to 792 a., encompassing most of the parish's southern half, and comprising (unusually for Oxfordshire) mainly grade one agricultural land. (fn. 260) The enlargement was partly achieved through St John's purchase of the Stapletons' estate, which added over 200 a. of strong, black land to the farm's north-east corner in 1937. The rent, initially 20s. per acre, rose by 1939 to 26s. 11d., slightly above the 1941 county average of 22s. 6d. (fn. 261) Warburton was an early exponent of mechanized grain production without livestock, and at first retained only four labourers; by the later 1930s, however, livestock had been reintroduced as an aid to soil fertility, and the number of workers was gradually increased to fourteen. Warburton struggled during the difficult early 1930s, supported by government wheat-deficiency payments. Thereafter he prospered, investing in improve ments (including 400-ton ventilated grain bins) which were partly reimbursed by the college. The college also paid for drainage and other structural improvements both at Shillingford and Upper farms, although farm roads remained poor. (fn. 262)

Warburton initially introduced a rotation of wheat, barley, and fallow, employing the latter (as well as chemicals) to tackle infestations of wild oats and charlock. From 1938–48 up to 110 a. were devoted to potatoes and market-garden crops, and by 1949 Warburton farmed 283 a. of barley, 188 a. of wheat, 80 a. of four-year pasture ley, 60 a. of clover, 44 a. of peas (sold for canning), and smaller areas of other crops and pasture. By 1957 he had added 91 beef cattle and a few pigs, and by then barley was being sold to major brewers, rather than (as earlier) to village maltsters. The pattern remained similar in 1961, when barley and wheat were supplemented by smaller areas of beans, hay, potatoes, rye grass, and pasture. (fn. 263)

From the late 1960s manpower on Shillingford farm fell gradually to only five labourers in 1969 and to two by 1979, echoing a reduction in labour-intensive crops such as potatoes and peas. The farm benefited from the higher yields provided by new strains of barley and wheat, and in 1978 achieved 47 hundredweights per acre of barley and 59 hundredweights per acre of wheat, considerably above the national average. (fn. 264) In 2006 it was leased to a contractor who farmed c.3,500 acres, including land in west Oxfordshire. The parish's second largest holding, Upper farm (235 a.), was for a time used for corn and beef cattle, and in the early 1970s became a large-scale pig farm with buildings on Town Hill. (fn. 265) In 2010 the manager and six staff kept 650 sows producing 15,600 bacon pigs per year, and wheat, barley and oil seed rape were grown for feed. A planned bio-gas plant was intended to generate electricity and to produce fertilizer from food waste and pig slurry. (fn. 266) Only one other small farm remained in the parish by the late 1980s, the rest of the land being cultivated from surrounding villages. The main crops were then wheat (709 a.) and barley (564 a.), and there were 191 a. of grassland, including rough grazing. (fn. 267) The area under wheat was subsequently increased.

TRADES, CRAFTS, INDUSTRY, AND RETAILING

The parish supported a fairly wide range of craftsmen and retailers from an early date, although even in the 19th century many of them were also involved in farming. During the Middle Ages several tenants were involved in brewing and baking, (fn. 268) and early 14th-century occupational surnames included 'fuller' and 'chapman'. (fn. 269) Shillingford had a watermill by the 13th century and perhaps in the 11th, (fn. 270) while fisheries in the Thames included one with a weir or fish trap ('wythegeyt') next to Shillingford bridge in 1310. (fn. 271) During the 17th century blacksmiths, masons, carpenters, wheelwrights, weavers, shoemakers, tailors, butchers, and maltsters were all recorded, (fn. 272) and though agriculture remained the main source of employment in the 19th century, rural craftsmen and traders continued to be well represented. (fn. 273) By the 18th century the two settlements also supported a number of public houses and inns, including several along the main Oxford–Henley road. (fn. 274) For much of the 19th century there were five or six pubs in operation, (fn. 275) and in 1895 the George in Shillingford was catering for boating parties and cyclists attracted by a nearby boat-hire business. (fn. 276)

Several maltsters operated during the 19th century, notably Benjamin Tubb (1768–1863), who bought Kentish hops and sold malt and barley in Maidstone, London, and the Midlands. (fn. 277) A brewery in Shillingford existed from the 1840s to 1890s, employing 21 workers in 1871; (fn. 278) the Field family, proprietors for most of that period, had premises in Wallingford, where they were also involved in the drapery business. (fn. 279) The brewery was subsequently replaced by the Shillingford Works, a short-lived brass foundry and electrical engineering works. (fn. 280) Maltsters, brewers, and local corn and coal dealers all benefited from the presence of Shillingford wharf, (fn. 281) which was used to ship coal, grain, malt, timber, and other goods, and which had a malthouse adjacent in 1848. (fn. 282) In 1771 1,050 tons of coal from London was offloaded at the wharf, (fn. 283) and three corn dealers lived in Shillingford in 1851. (fn. 284)

Several shopkeepers, bakers, and grocers continued in the earlier 20th century, but by 1973 only a village store and the sub-post office remained. (fn. 285) Some inhabitants worked as wood-carvers for a Dorchester firm, chiefly producing pine mantelpieces for export, (fn. 286) while in the south of the parish a carp fishery established in the 1950s was revived in 2003. (fn. 287) By 1978 many inhabitants commuted to Oxford, Cowley, Reading, or London, (fn. 288) and in 2001 76 per cent of those in work were employed in the service sector, most of them at managerial and professional level. The unemployment rate (1.8 per cent) was around the south Oxfordshire average, although below the wider south-east region figure of 2.3 per cent. (fn. 289)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Warborough was a vibrant 'open' parish by the 18th century: the major landowners were absentees, and the mixed population included numerous small freeholders as well as customary tenants, while a dominant farming sector was complemented by craft and trade activities. Nonconformity was also strong. (fn. 290) Good road and river communications strengthened links with nearby Dorchester, Benson, and Wallingford, and also with more distant places including London. The number of affluent residents increased in the late 19th century, and though village society remained socially mixed, from the 1960s the two settlements were linked by new houses built for commuters and professionals. Other prosperous incomers bought formerly modest houses around Warborough Green. (fn. 291)

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

Little is known about Warborough's social structure before the 13th century, although the Domesday population presumably included sokemen, villani, lower-status bordars, and some or all of the Benson estate's five servi or demesne workers. (fn. 292) By 1279 social stratification was reflected partly through types of tenure: a few held land freely by charter for small money rents, and a large group of sokemen and customary tenants owed limited labour services, commuted soon afterwards. The customary tenants also required the lord's permis sion to give their daughters in marriage. (fn. 293) Divisions were not clear-cut, however. Some tenants held land by more than one kind of tenure, and gradations in size of holding (which cut across tenurial distinctions) were equally important. Over two thirds of the tenant population held half yardlands or less, while c.15 per cent had whole yardlands, and a few leading individu als held more land or other assets. (fn. 294) The latter included William le Totere, a sokeman with two yardlands (one held freely), whose daughter married a Newington man in 1286. (fn. 295) Another was Richard Rastwold, a substantial Benson freeman who held a yardland, a mill, and other property in Shillingford. (fn. 296) The Rastwolds remained in the area in the 14th century. (fn. 297)

In 1306, 24 Warborough tenants paid between 7d. and 5s. 1d. in tax, the highest sum coming from Thomas Battle; in Shillingford, twelve taxpayers paid between 6d. and 3s. 5d., and the abbess of Godstow paid 11s. 4d. (fn. 298) The range of tenant wealth was fairly typical for the area, though Warborough taxpayers were consid erably better off than their Shillingford counterparts. Eighty per cent of the families taxed had been pres ent in 1279, and c.60 per cent remained in 1329, with greater continuity in Shillingford than in Warborough. (fn. 299) Unsurprisingly, turnover of population and social stratification seem to have increased after the Black Death. By 1380 the majority of taxpayers were newcomers, and some were clearly prosperous: John Reading, for instance, had three servants, and five others had one or two. (fn. 300) Nevertheless some long-standing families remained into the 15th century. Richard Osgood, for example, a Dorchester bailiff and rectory farmer in the 1440s, was presumably descended from the Osgoods mentioned in 1279. (fn. 301)

In the later Middle Ages Warborough and its church probably acted as a social and religious focus for inhabitants of the smaller settlement at Shillingford, although the latter had its own manor court. (fn. 302) There were also strong outside connections. Both places remained ecclesiastically dependent on nearby Dorchester, and until the mid 17th century many local people seem to have been buried in the churchyard there. (fn. 303) Landholding links persisted with Benson (the manorial centre) and Wallingford (the nearest market town), (fn. 304) while intercommoning continued with surrounding settlements. (fn. 305)

1500–1800

In the absence of resident gentry, local society continued to be headed by leading farmers. Some yeoman families remained through much of the period, among them the Gammons, Butlers, Hobbeses, and Beisleys, (fn. 306) of whom many served as churchwardens or overseers. The Beisleys were especially prolific, with branches involved in farming and building. In the 16th century Shillingford was dominated by the Randolphs, who were lessees of Shillingford farm and constables of the tithing group. (fn. 307) Warborough had a larger number of substantial tenants, including the long-standing Phelp family: in 1563 William Phelp held five yardlands from St John's College, (fn. 308) and in 1665 Richard Phelp had a house with eight hearths, and William Phelp one with four. (fn. 309) Even wealthier was William Beisley (d. 1684), a gentleman farmer who in 1681 devised an estate worth £1,200, (fn. 310) by far the largest recorded in the parish in the 16th or 17th centuries. Leading parishioners in the later 17th and 18th centuries included the Herberts, of whom several (including Rose Herbert in 1747) served as churchwarden. (fn. 311) Warborough's curates (or sometimes their substitute clergy) seem to have also developed close links with the local community, though from the mid 17th century they were in competition with Nonconformist ministers. (fn. 312)

The wealth of the leading farmers, like that of other inhabitants, was tied up mainly in agricultural equipment and produce. Probate inventories suggest an increase during the 17th century in the amount of domestic furniture, feather beds, linen, brass and pewter, but real luxuries, like silver, remained rare. (fn. 313) Only two inventories from the period 1600–40 were worth over £200, increasing to nine between 1640 and 1688; two of the highest, however, those of Thomas Hobbes (c.£270 in 1649) and his son Adam (£531 in 1666), included the lease of the parsonage at Overy (Dorchester), latterly worth £300. (fn. 314) In 1640–88, 23 out of 40 inventories were worth less than £50. (fn. 315) Craftsmen were fairly poor, and had few specialist tools. (fn. 316)

In the 16th and 17th centuries those making wills probably represented less than a fifth of the total population. (fn. 317) The rest, whose goods were probably worth less than £5, presumably included wage labourers, smallholders, and some widows, though copyholders' widows normally received their late husbands' lands for life. (fn. 318) There was apparently a considerable turnover among poorer inhabitants, especially when real wages were low, as in 1600–10. (fn. 319) Many girls and younger sons left the parish to become servants elsewhere. (fn. 320)

The geographical range of villagers' regular social and business contacts was relatively limited, although their frequency perhaps increased after the Civil War. (fn. 321) The places most often mentioned in probate and other documents were Wallingford, Watlington, Thame, Abingdon, Oxford, and villages in the surrounding clay vale. As elsewhere, a degree of social polarization may have occurred within the parish during the 17th century: among richer inhabitants there was apparently a strengthening of social contacts with their peers from a slightly wider area, and a weakening of ties of extended family. Nevertheless, strong elements of co-operation continued at all levels, as evidenced in the operation of open-field agriculture and small-scale village lending. There are few indications of serious social conflict, though Nonconformist worship troubled the incumbents and may well have created some wider tensions. (fn. 322)

In the 18th century the two settlements continued to be dominated by farmers, of whom some were accumulating larger holdings and could afford stone table tombs as memorials. Craftsmen, traders, and maltsters were also well represented. (fn. 323) The leading farmers and corn dealers kept a few servants and lived in larger and more elaborate houses, several of which were built in Wharf Road in Shillingford; new cottages and tenements also appeared around Warborough Green and elsewhere, as the number of agricultural labourers increased. (fn. 324) Pubs and inns provided a social focus, sometimes hosting pigeon-shooting competitions, auctions, and other events. (fn. 325)

Since 1800

Similar patterns continued in the early 19th century, when a dozen farmers and several others lived in fairly large and comfortable houses. The Tubbs, a well-connected family of maltsters, coal dealers, and farmers resident from c.1802, enjoyed frequent trips to Wallingford and other nearby towns and villages, as well as to London and further afield; (fn. 326) the men of the family were involved in reformist politics, especially James Tubb I (1763–1846), who lived in the parish from 1820 and was an associate of William Cobbett. (fn. 327) Below this village élite was a mixed group of smallholders, traders, and especially agricultural labourers, (fn. 328) the poorest of whom, in the absence of a paternalistic resident landowner, lived in 'The College', a 'nest of hovels' by Warborough church. (fn. 329)

A 'grand festival' to celebrate the passing of the Reform Act was held at Warborough on 14 July 1832, in which 'young and old, rich and poor' apparently joined together. (fn. 330) Nonetheless the social and economic changes of the period caused local tensions. (fn. 331) Farmers struggled to reduce high expenditure on poor relief, (fn. 332) and some labourers apparently sought to protect their interests against mechanization through what an unfriendly source called 'The Warborough Badger Club' or 'Crow Bar Society'. (fn. 333) This was allegedly full of 'cadgers' from 'The College' and, it was claimed, 'a fat old Tubb', presumably James. Tubb's reformism had its limits, since he prosecuted two rioters in 1828; (fn. 334) even so the absence of any prominent local champions of inclosure probably kept disturbances at a lower level than in neighbouring Benson. (fn. 335)

The complexity of social relations was further exposed at inclosure. The perpetual curate Herbert White defended the social interests of the poor and sought improvements in housing, (fn. 336) and he and Joseph Tubb (James Tubb I's nephew) resented what they saw as the greed of absentee landowners. Conversely other members of the Tubb family attended St John's College rent dinners and bought land at inclosure, (fn. 337) while White and Tubb's nostalgic and conservative defence of the traditional countryside moved them to oppose (unsuccessfully) the creation of allotments for the poor on part of Warborough Green. (fn. 338) White also tried to end a September Sunday fair held in connection with Warborough feast, partly because beer was sold there. (fn. 339)

In the later 19th century the parish's social character gradually began to change. The number of private residents rose from eight in 1853 to eighteen in 1883 (mainly in Warborough), and to 30 in 1911 (15 in each settlement). (fn. 340) Wealthier incomers were probably drawn by the parish's good transport links, stock of larger houses, attractive setting (including leafy roads, wide verges, and a fine green), and proximity to the Thames, with views towards Wittenham Clumps and the Chiltern Hills. (fn. 341) Nevertheless the bulk of the population continued to be of much more modest means, and were mainly employed in farming, trades, brewing, (fn. 342) and, increasingly, domestic service. Many had been born in the parish. (fn. 343)

In the earlier 20th century the population remained socially mixed, with many local families still involved in trades, retailing and agriculture. (fn. 344) A number of new council houses were built in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and larger-scale development in the 1960s–70s included some council houses and flats. (fn. 345) By 1970 there were few local tradespeople, however, and most of the population had been resident for less than twenty years. (fn. 346) The incomers were mainly affluent commuters, and the number of households in council-owned accommodation almost halved in the twenty years after 1981. In 2001 there were 302 owner-occupiers, 56 households renting from private landlords, and 47 renting from the local authority. (fn. 347)

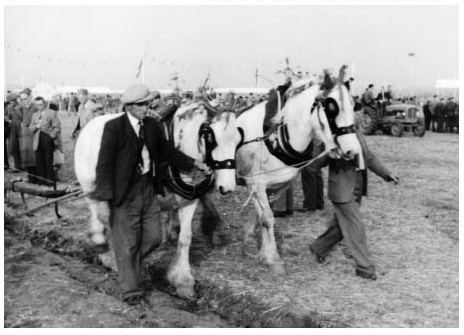

Participants in the fourth world ploughing contest, held near Shillingford in 1956.

Warborough continued to be the livelier of the two settlements and the main social focus for those living in Shillingford. In the earlier 20th century it had branches of the Mothers' Union and Women's Institute (formed in 1925), scouting and other youth clubs, and a successful country dance group. (fn. 348) Many such clubs met in the Greet Memorial Hall (a converted barn given by a local family of that name), in the Caldicott Hall (a former Methodist chapel), and from the early 1970s in the former National school (renamed St Laurence Hall). (fn. 349) Celebrations were held for national events such as the Silver Jubilee in 1935 and the coronation in 1953, while the world ploughing contest was held on farmland near the village in 1956, and the annual harvest festival remained an important social event in the 1960s. (fn. 350) In the early 21st century cricket, football, and other events took place on Warborough Green as they had in the 19th, (fn. 351) and there were numerous community groups. (fn. 352) From 1970 residents also grouped together to address concerns over housing development, road-building, traffic levels, and gravel extraction. (fn. 353) In the early 1980s the Nag's Head (or Dirty Nelly's) near the church had a reputation as a rough drinking pub, (fn. 354) but this had been shed before its closure in 2002. Several other pubs closed around the same time, though the Six Bells remained in 2015.

EDUCATION

In the 16th century a few parents paid to educate their children, (fn. 355) perhaps in the 'house for teaching boys good letters' located close to the church in 1606. (fn. 356) This may have been the long-established and popular unendowed day school mentioned in the early 19th century, which provided reading, writing and arithmetic to the 'better sort' and to poor children sent by the rector and others. (fn. 357) It was joined by a Sunday school in 1808. (fn. 358) Nonetheless, illiteracy seems to have been widespread. (fn. 359) By 1835 there were four day schools instructing 44 children at their parents' expense, and 71 children attended the Sunday school, which was supported by subscription. (fn. 360)

A National school was built in 1838–9, following fundraising by Herbert White, the perpetual curate. (fn. 361) The school, located on a small piece of land on Thame road near the church, was initially well regarded, (fn. 362) and in 1853 average attendance was around 70. (fn. 363) An infant classroom was added in 1871, increasing accommodation to c.130, (fn. 364) although daily attendance remained c.70–80. (fn. 365) In 1902 the school came under the authority of the county council, and in 1927 it was redesignated as a junior school; pupils aged over eleven had to cycle the 2 miles to Dorchester. (fn. 366) Pupils numbers totaled c.100–120 from 1900 to 1922, but declined thereafter, dropping from 68 to 51 in 1927–8. (fn. 367)

Under the 1944 Education Act the school became 'aided' rather than 'controlled', thanks partly to funds raised by the perpetual curate, Canon Barker. (fn. 368) Numbers were bolstered from 1934–57 by the presence of three county council children's homes in Shillingford. (fn. 369) The school was replaced in 1962 by the new St Laurence Church of England primary school, opened on a larger site at the southern end of the village, which had 65 pupils in 1979, 74 in 2002, and 41 in 2010. (fn. 370) A community playgroup for toddlers, established in 1966, became a formal pre-school in 2007, based in a building in the school grounds. (fn. 371) Most local children attended secondary school in Wallingford, though some went to private schools. (fn. 372)

POOR RELIEF AND CHARITIES

In the late 16th and early 17th century parishioners zade small bequests to the poor, (fn. 373) some of whom apparently lived in common-side cottages. (fn. 374) Bequests fell away after the Civil War, presumably because greater provision was made through the poor rate. (fn. 375) In the first half of the 18th century rates were low at just a few pence in the pound, (fn. 376) and in 1751 (when a roundsman system was in operation) they remained 'very moderate'. (fn. 377) Rates increased in the later 18th century and rose sharply by 1801, (fn. 378) presumably reflecting (as in other 'open' parishes) an increase in the laboring population. (fn. 379) From 1784 to 1794, 31 per cent of those buried in Warborough were paupers exempt from burial tax. (fn. 380)

By 1803 the poor rate of 7s. 11d. in the pound was the third highest in the hundred (after Ewelme and Nettlebed), (fn. 381) and expenditure remained high, despite a marked increase in pauper removals (fn. 382) and considerable expenditure on lawsuits. (fn. 383) Costs were particularly great in the 1810s, dropping substantially in 1821, but rising again in 1822. (fn. 384) A select vestry established in December 1821 may have helped prevent further sharp rises, (fn. 385) and the surplus of labourers had disappeared by 1851. (fn. 386) Formal responsibility for the poor passed to the Wallingford Poor Law Union in 1834. (fn. 387)

An endowed charity left by William Beisley was received from 1711, providing £5 a year for clothes for a dozen poor people. In the early 19th century tickets were issued for articles worth 8s. 4d. from a mercer's shop in the village, and from 1830 a bequest from the weaver John Sargood (d. 1826) augmented the charity by c.£3 a year, the clothes to go to ten poor inhabitants not on permanent relief. (fn. 388) Harriet Beisley of Sydenham left £400 in 1896 to provide coal for the poor at Christmas. (fn. 389) All three charities continued into the mid 20th century, but apparently ceased thereafter. (fn. 390)

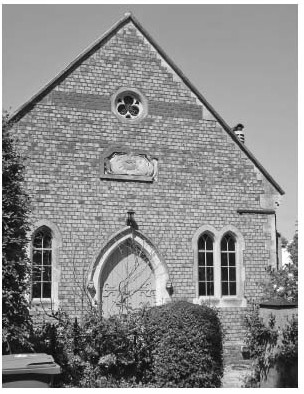

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

In the Middle Ages Warborough was a chapelry of Dorchester, but had its own endowment (appropriated to Dorchester abbey), and seems to have functioned largely as an independent parish, evolving eventually into a perpetual curacy. The parish remained under the jurisdiction of the peculiar of Dorchester until the early 19th century, its ecclesiastical revenues appropriated from the 1530s to Corpus Christi College, Oxford. During the 17th and 18th centuries the Anglican Church was unevenly served, latterly by pluralists, but there were improvements in the 19th and 20th centuries. Nonconformity was strong, first in the form of Catholic recusancy and later, from the 1650s, through Quaker and other Protestant meetings. By the 1850s there was a Baptist meeting house and a Wesleyan Methodist chapel, besides a long-established Friends' meeting house. Nonconformity died out in the early 20th century.

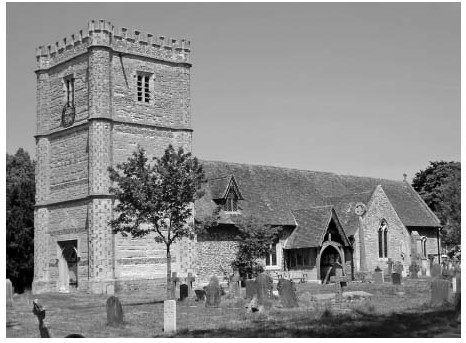

CHURCH ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

In the 11th century Warborough (as part of the Benson royal estate) was presumably subject to Benson church, and nominally remained so in 1279. By then, however, Benson's status had been downgraded following its grant to Dorchester abbey c.1140–2, apparently along with Warborough and its other dependencies. (fn. 391) Whether Warborough already had a chapel by that date is unclear, but parts of the surviving building date from c.1200, and its lead font may be slightly earlier. (fn. 392) The location of the church and early rectory house on Warborough Green, the presence of numerous free sokemen, and the absence of any manor house all suggest that its foundation may have been a 'communal' as much as a 'lordly' initiative. (fn. 393)

Warborough continued to be regarded as a chapelry of Dorchester throughout the Middle Ages, (fn. 394) and was usually described as part of Dorchester parish until the mid 17th century. (fn. 395) Before then wealthier inhabitants (and possibly others) were usually buried at Dorchester, and an obligation to maintain part of the railings of Dorchester churchyard survived into the 19th century. (fn. 396) In other respects Warborough effectively functioned as a separate parish from the medieval period. (fn. 397) It remained part of Dorchester peculiar until 1846, (fn. 398) although for some years before that it was at least partly under the bishop's jurisdiction. (fn. 399) The dedication to St Laurence seems not to be mentioned before the 18th century. (fn. 400)