Pages 275-302

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

NETTLEBED

Nettlebed lies in the Chiltern hills c.8 km north-west of Henley-on-Thames. (fn. 1) The village developed along the main Oxford-Henley road (turnpiked in 1736), and besides the church includes several former inns which served the coaching trade. Houses and farms elsewhere in the parish are more scattered, producing the dispersed settlement characteristic of the Chiltern uplands, but with loose clusters at Huntercombe End, Crocker End, and Soundess. During the 20th century the parish's convenient location and attractive surroundings encouraged residential development, more than doubling the number of households to almost 300.

Nettlebed's lords were mostly non-resident, but Manor Farm may mark a medieval manorial site, and other landowners established mansion houses at Soundess and Joyce Grove probably in the 17th century. The latter was rebuilt in Jacobean style in 1904–5. From the Middle Ages to the early 20th century Nettlebed was also an important centre of brick, tile, and pottery manufacture, providing alternative employment in what was otherwise (save for its inns and services) a predominantly agricultural parish.

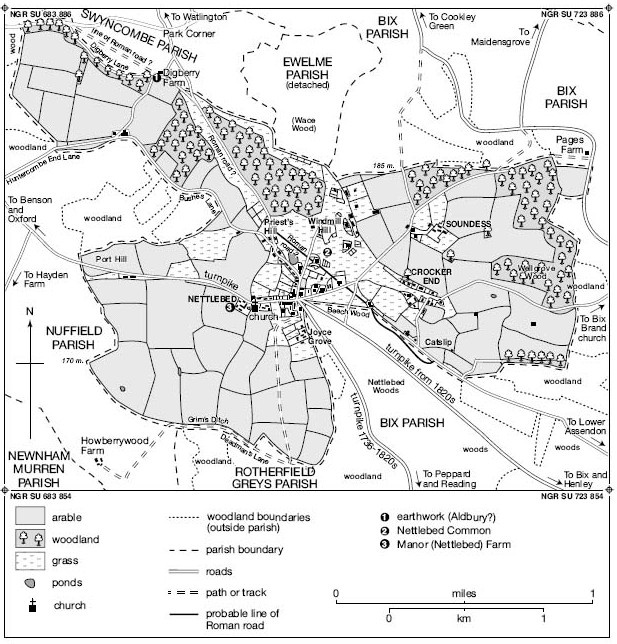

PARISH BOUNDARIES

Until 1952 the ancient parish covered 1,172 acres. (fn. 2) Its northern and eastern boundaries (with Bix and Rotherfield Greys) followed those of the hundred, mostly along woodland and field divisions, while other stretches followed the Iron-Age earthwork known as Grim's Ditch, and at Catslip the former Roman road from Dorchester to Henley (fn. 3) The northern boundary with Swyncombe followed Digberry Lane, while that to the west (with Nuffield) ran along Huntercombe End Lane and Bushes Lane, crossing the Henley road at Port Hill and following field divisions to Deadman's Lane.

Some of those boundaries were defined before 1086 by the creation of neighbouring estates at Bix, Rotherfield Greys, and Swyncombe, which probably accounts for a tongue-like incursion from Bix in the south-east, allocating valuable woodland to Bix's 11th-century manors. (fn. 4) A similar partition of resources on the west may explain a comparable incursion from Nuffield. Otherwise, Nettlebed seems to have emerged relatively late as a distinct territorial unit. A separate Nettlebed manor was carved from the Benson royal estate only in the mid-to-late 13th century, and though a church existed probably by the mid 12th century, its status was long in doubt and its ecclesiastical boundaries may not have been fully determined. The extent of Nettlebed's early open fields, if any, is also unknown. (fn. 5)

In 1952 the parish gained 349 a. (mostly woodland south-east of the village) from Bix, bringing its area to 1,521 a. (616 ha.). (fn. 6) Around 7½ a. (3 ha.) in the north-east was transferred to Bix in the early 21st century. (fn. 7)

LANDSCAPE

Nettlebed is a hilltop village towards the south-western end of the Chiltern hills. The parish's highest point, at Windmill Hill, reaches 211 m., and was the site of a warning beacon in the 16th century. A bonfire on the Malvern hills, 73 miles to the north-west, was reportedly seen from its summit in the 1850s. (fn. 8) The relief is uneven, especially on the parish's eastern side, where the ground falls steeply down a dry valley to c.115 m. at Wellgrove Wood. The village lies at c.180 m. on the edge of the Chilterns dip slope, which shelves south-eastwards to flatter ground by the Thames.

The underlying geology is chalk, but much of the parish, including the village and its associated settlements of Crocker End and Soundess, lies on an extensive mantle of clay-with-flints. The higher ground of Windmill Hill is capped by the older sandy clays of the Reading Beds and London Clay, providing the essential raw materials for the parish's long-standing brickmaking and pottery industries, (fn. 9) while rare interglacial deposits at nearby Priest's Hill have led to its designation as a Site of Special Scientific Interest. (fn. 10) As elsewhere in the Oxfordshire Chilterns the parish is extensively wooded, and marked (particularly around the common) by numerous former chalk and clay pits dug for both agricultural and industrial purposes. (fn. 11) Wells, clay-lined ponds, and rain-water cisterns remained the main source of water until the 20th century, (fn. 12) reputedly supplemented by an unidentified spring which never ran dry. (fn. 13) As at Nuffield, water may sometimes have had to be carted in. (fn. 14)

Nettlebed parish in 1840. (For common see also Fig. 80.)

The view from Windmill Hill was much admired in the late 19th century, (fn. 15) overlooking distinctive features of the parish's Chiltern landscape: woodland, heath, common, anciently inclosed arable fields, deep dry valleys, isolated farms, brick and tile kilns, and narrow, winding lanes. (fn. 16) Two medieval deer parks extended into the parish, (fn. 17) and the dissected and wooded hills continued to provide good hunting country, enjoyed by at least one of Nettlebed's 18th-century clergymen. Its remote and secluded character also sheltered highwaymen and thieves. (fn. 18) The present-day parish remains relatively unspoiled despite extensive house-building, with trees and undergrowth spreading across the commons former clay workings, and screening a water reservoir and pumping station at the former windmill site. (fn. 19) The common itself now forms part of the Nettlebed and District Commons, protected by Act of Parliament and totalling 560 a. in Nettlebed and neighbouring parishes. (fn. 20)

COMMUNICATIONS

Roads

The village developed along the Oxford-Henley road near its intersection with roads to Watlington and Reading. (fn. 21) The Henley road's Roman predecessor took a rather different course, running probably along a surviving lane at Catslip, although much of its route through the parish remains uncertain. (fn. 22) From the Middle Ages the Henley road formed part of a major route to London, (fn. 23) and was turnpiked in 1736, improvements c.1826–7 including a minor diversion on the parish's western edge at Port Hill. (fn. 24) The route was disturnpiked in 1873. (fn. 25) The Watlington road, crossing Nettlebed Common west of Windmill Hill, may have formed part of a prehistoric or Anglo-Saxon ridgeway, (fn. 26) and in the 13th century was apparently called Reading way (fn. 27)

Other probably medieval routes include lanes from Crocker End eastwards to Bix Brand church, and to the former Roman road at Catslip, while a lane from Nettlebed village leads north-eastwards past Soundess to Maidensgrove (in Pishill). (fn. 28) One of those was perhaps the medieval Cobbe Lane, rendered almost impassable in the late 14th century by the collapse of its banks. (fn. 29) Several roads in the parish's north-western part formed stretches of parish boundary, amongst them Huntercombe End Lane, which links the Henley and Watlington roads and may have been a focus of early medieval settlement. (fn. 30)

The main Henley, Watlington, and Reading roads were improved during the 20th century, and access roads to Crocker and Huntercombe Ends were maintained. Several lesser routes survived as footpaths or bridleways, some leading southwards to Highmoor, or northwards to Russell's Water and Cookley Green. (fn. 31)

Coaching, Carriers, and Post (fn. 32)

From the mid 17th century Nettlebed's location on a main Oxford-London road and postal route ensured that it was well served by coaches and carriers. A post-chaise operating between London and Faringdon was owned by a Nettlebed innkeeper in the 1750s, (fn. 33) when long-distance travellers frequently broke journeys at Nettlebed, (fn. 34) and by 1830 coaches to Gloucester, Stroud, and Holyhead passed through regularly. (fn. 35) Parish-based carriers serving Henley and Reading operated by the mid 1870s until c.1935, when they were superseded by motorized buses to Henley, Wallingford, Reading, and Watlington, established from the 1920s. Local bus services continued in 2011. (fn. 36)

In the 1660s post sent from Oxford reached Nettlebed twelve hours later. (fn. 37) A Nettlebed innkeeper served as postmaster by the 1670s, and the village remained a significant 'post town' throughout the 18th century. (fn. 38) By 1830 the post office (owned and run by William Rhodes) adjoined the Bull Inn on High Street, and distributed mail to surrounding parishes; (fn. 39) thereafter it remained the area's main office save for that at Henley, doubling from the 1870s as a money order office and savings bank, and from the 1890s as a telegraph office. (fn. 40) By the 1870s it had moved to Watlington Street, where it remained (except for a brief return to High Street in the early 20th century) until 2010. Thereafter it moved to the old school building on High Street. (fn. 41) Crocker End had a wall letter box by 1899. (fn. 42)

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

Prehistoric to Anglo-Saxon Settlement

Mesolithic flint-working sites found on Nettlebed Common were probably seasonally occupied by groups of hunter-gatherers, (fn. 43) and undated enclosures near Digberry Lane are of possibly Neolithic or Bronze-Age date, although their significance is unclear. (fn. 44) An earthwork on the parish boundary along Deadman's Lane is most likely an eastwards continuation of the Iron-Age Grim's Ditch, suggesting seasonal settlement in an area of upland grazing. (fn. 45) Roman activity is poorly attested except by the road and a 1st-century coin found in Nettlebed village, although evidence of settlement and industry has been found nearby. (fn. 46) A massive earthwork enclosure straddling the parish boundary at Digberry Farm (and enclosing c.10 a.) adjoins the probable Roman road, but is undated. (fn. 47) By the 13th century it was apparently known as Aldbury ('old burh or fortified enclosure'). (fn. 48)

Nettlebed's Anglo-Saxon place name means a place overgrown with nettles, (fn. 49) suggesting clearance of former waste. Early activity may be indicated by a 5th- to 6th-century pottery fragment found at Windmill Hill, (fn. 50) with later colonization perhaps associated with development of the Benson royal estate, to which Nettlebed belonged throughout the late Anglo-Saxon period. (fn. 51)

Population from 1086

Domesday Book and the Hundred Roll survey of 1279 both subsumed Nettlebed under descriptions of Benson manor, an unknown number of whose tenants may have lived in Nettlebed parish. (fn. 52) Only seven Nettlebed landholders were taxed in 1306, suggesting either a relatively small community or one in which most inhabitants were too poor to be assessed, (fn. 53) and mid 14th-century plague apparently reduced the population further: ruined houses were demolished in the 1360s, and in 1377 Nettlebed was again joined with Benson for collection of poll tax. (fn. 54) Consolidation of tenants' landholdings in the late 15th century suggests that population remained at low levels, (fn. 55) and in the early 16th century Nettlebed's taxes were assessed with those for other places: 39 heads of household contributed in 1524, and 19 (in Nettlebed alone) in 1543, (fn. 56) while 14 tenants held land at Soundess in 1537–8. (fn. 57) Sixty-three people were recorded in the parish in 1548, and 12 inhabitants paid tax in 1581, one of the highest figures in the hundred. (fn. 58)

From the 1650s baptisms consistently outnumbered burials, (fn. 59) with 32 households assessed for hearth tax in 1665, and 152 adults noted in 1676. (fn. 60) Around 60 houses and a population of 200 were reported in 1718, (fn. 61) and after a sharp fall in the 1740s average numbers of baptisms and burials both rose over the period 1750–99. (fn. 62) By 1801 there were 99 houses and a population of 501, reaching a peak of 754 (in 145 houses) in 1851. Thereafter numbers fell to 657 (in 151 houses) in 1881 and to 544 (133 houses) in 1901, partly reflecting agricultural depression. After a period of stability the population rose to 688 (in 184 houses) by 1951, following which boundary changes added 367 people from Bix. Nevertheless in 1961 there were only 758 people in 225 houses, falling to 677 (in 272 houses) by 1991. In 2011 the parish's population was 727, a total of 296 households. (fn. 63)

Medieval and Later Settlement

Medieval settlement remained dispersed, with at least four distinct areas inhabited in the Middle Ages: Nettlebed village, Huntercombe End (which lay mostly in Nuffield), Crocker End, and Soundess. The last was named after its medieval owners (the Soundy family), while the name Crocker End (recorded from 1416–17) suggests early association with Nettlebed's pottery and tile industry. (fn. 64) All four places were shown on 18th-century maps, when the small greens around which Crocker End and Huntercombe End developed remained clearly visible (see Fig. 75). (fn. 65) In the early 14th century there was also habitation near the Digberry Lane earthwork, possibly over the Swyncombe boundary around Digberry Farm. (fn. 66)

Nettlebed's main street c.1909, looking west; the pedimented front of the Bull Inn is on the left part way down.

Nettlebed village itself developed along the Henley-Oxford road, plots at its western end containing the church (established apparently by the late 12th century) and the adjoining Manor Farm (almost certainly on the site of medieval manorial buildings). (fn. 67) Probably it remained the most heavily populated area from the Middle Ages, and in 1840 contained 75 houses compared with Crocker Ends 25. (fn. 68) Soundess seems to have remained a sizeable settlement in the 1530s, when tenants' rents comprised the considerable sum of £5 16s. 11d. a year. (fn. 69) It was most likely cleared in the late 16th or early 17th century when the Taverner family built a mansion house there, and thenceforth Soundess formed a single estate or farm. (fn. 70) By the 17th century houses were also being built along the former Roman road at Catslip and Beechwood, on the roadside at Port Hill, and on Nettlebed Common by Windmill Hill; (fn. 71) colonization of the common was almost certainly promoted by the expansion of brickmaking, and the number of houses there subsequently increased from 12 in 1840 to around 20 by 1901. (fn. 72) Housing quality among the poor remained generally low, and sanitary provision inadequate. (fn. 73)

In the 20th century new private and local-authority housing was developed between Bushes Lane and Watlington Street, and on formerly open ground north of High Street. Smaller areas of infill included the former pottery works (closed in 1938), contributing to an over-all increase of c.75 households between 1961 and 2001. Some older properties were simultaneously restored and improved, many by affluent incomers. (fn. 74)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Nettlebed's buildings display little uniformity beyond that fashioned by individual builders and landowners. (fn. 75) Brick, much of it from local kilns, (fn. 76) is by far the commonest material, particularly along Nettlebed High Street where smart frontages featuring sash windows, symmetrical façades, and decorative use of red and grey brick reflect rebuilding during Nettlebed's prosperous coaching period. (fn. 77) Examples include Nettlebed House, Small House, 7 High Street, and the Rectory, (fn. 78) as well as the extended 18th-century frontage of the Bull Inn (Plate 10), with a central pediment over the carriage entry, and a roof constructed of imported Baltic pine. (fn. 79) Flint with brick dressings was also used to striking effect, as at Manor (formerly Nettlebed) Farm and the White Hart Hotel. (fn. 80) Surviving internal decoration includes an interlaced design enclosing a floral pattern in a first-floor chamber at the Bull, of a type common in 16th-century inns, while plaster heraldic panels survive in the cottage adjoining the White Hart, also in an upper-floor chamber. (fn. 81)

Earlier, timber-framing was also common. A small cruck-framed cottage at Crocker End, dendro-dated to c.1415, acquired a box-framed cross wing in 1441, (fn. 82) while 16th- or 17th-century timber-framing survives elsewhere at Crocker End, on Watlington Street, and at 15 and 17 High Street, sometimes associated (as at 7–8 Watlington Street) with up-to-date lobby entry plans. Most such framing was subsequently infilled with brick, or (as at 6 and 7–8 Watlington Street) rendered and whitewashed. (fn. 83) Rubble walls are rarer, exceptions including Bees Cottage in Crocker End and 25 High Street. (fn. 84) Tiles on abandoned houses were mentioned in 1363, (fn. 85) and were presumably locally made, although thatch was probably also common, and continued on some agricultural buildings into the early 19th century. (fn. 86) Dome-shaped and brick-lined water-storage cisterns survive at several cottages and farmhouses, many of them carefully constructed. (fn. 87)

From the 17th century modernization and rebuilding seems to have followed the usual pattern, including insertion of floors and chimneys and refronting in brick. (fn. 88) Nevertheless three quarters of houses assessed for hearth tax in 1665 remained small, assessed on only one or two hearths, while most larger houses (assessed on 3–12 hearths) included inns, farmhouses, and the outlying gentry residences at Joyce Grove and Soundess. Both those houses were rebuilt on a grand scale in the early 20th century, (fn. 89) new buildings in the village including the gothic-style flint-built school of 1846, and a distinctive Arts-and-Crafts working men's club designed by C.E. Mallows in 1912. (fn. 90) Most other 20th-century building was unexceptional.

MANORS AND ESTATES

Nettlebed belonged to the royal manor of Benson until the 13th century, (fn. 91) when a separate Nettlebed manor (held of the honor of Wallingford) was first created. Held from 1284 to 1362 by Rewley abbey, it subsequently reverted to the Crown, which granted it to royal servants until its acquisition by the Stonor family in the 16th or 17th century. They sold it in 1894 when it covered c.412 a. (just over a third of the parish), and during the 20th century it became absorbed into the Fleming family's large 'Nettlebed estate', which extended into neighbouring parishes. A nominal link with Benson continued in 1826, when jurors claimed that the whole parish remained within Benson manor's jurisdiction. (fn. 92)

Both Dorchester and Rewley abbeys acquired additional lands in the early 14th century, Dorchester's forming part of its larger estates at Huntercombe and Soundess. From the Dissolution Soundess (then called a manor) passed to mostly resident lay owners, and in the early 19th century covered over 320 acres. A few other freeholds were mentioned from the Middle Ages, and in the 1840s c.10 mostly minor owners had land in the parish. (fn. 93) Both Marsh Baldon and Huntercombe manors extended into Nettlebed, (fn. 94) while the tiny rectory estate (including 8 a. of grass and wood in the 1660s) belonged first to Dorchester abbey and later to the Stonors. (fn. 95)

NETTLEBED MANOR

In the mid-to-late 13th century Richard, earl of Cornwall, or his son Edmund, as lords of Benson, granted an independent manor of Nettlebed to John de Mandeville (d. 1275), who was succeeded by his under-age son John. (fn. 96) He may have been deprived, however, since in 1284 the manor was apparently included in a grant by Edmund to Rewley abbey, along with his 'whole wood at Nettlebed' and two parks called Highmoor. (fn. 97) The abbey acquired additional small parcels from two tenants-in-chief in 1303, when Edmunds widow Margaret claimed dower in a third of its alleged 2,000 a. of wood in Nettlebed and Benson. (fn. 98) In 1362 the abbey exchanged the manor for lands in Cornwall with Edward the Black Prince (d. 1376), whose widow Joan (d. 1385) was assigned it in dower. (fn. 99) Thereafter it reverted to the Crown and was given to Richard II's chamber knight Sir John Salisbury, executed in 1387. (fn. 100)

In 1393 the manor was bestowed for life on Thomas Hatfield, a minor member of Richard II's household, and in 1414 on another royal servant, William Bangor. (fn. 101) His life possession was confirmed in 1423 when his rent formed part of the dower awarded to Queen Catherine (d. 1437), (fn. 102) and in 1443 Henry VI re-granted the manor in survivorship to Bangor and a royal porter, John Watts. (fn. 103) From the late 15th to the mid 16th century the Crown leased the demesne to unnamed farmers and appointed bailiffs to collect the rents, (fn. 104) but in 1544–5 the manor was briefly granted to a London mercer, (fn. 105) and in 1547 to Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley. On his fall in 1549 it was granted to William Grey (d. 1562), Baron Grey of Wilton, and John Bannaster, for their service against the Scots. (fn. 106)

The date and circumstances of the Stonors' acquisition of the manor are uncertain: neither Sir Francis Stonor (d. 1564) nor his son Sir Francis (d. 1625) appear to have held it at their deaths, though both held lands in the parish. (fn. 107) In 1585, however, it was among manors forfeited by Lady Cecily Stonor (the elder Sir Francis's widow) for recusancy, and the Crown subsequently leased it to her son, who was then a conformist. (fn. 108) Sir Francis Stonor's lordship was contested by Thomas Box (d. 1610), who claimed that his father William had bought the manor from Grey and Bannaster: Box certainly owned land in the parish and was an active inclosing farmer, with interests in the woodland and former parks. (fn. 109) Whatever the case the Stonors regained possession, and from the mid 17th century until its sale in 1894 Nettlebed descended with Stonor manor. (fn. 110)

In 1894 the manor was bought by H.H. Gardiner, a London businessman who was forced to sell following financial losses. (fn. 111) Robert Fleming (1845–1933), a Scottish financier, bought the estate in 1903 and built a new mansion house at Joyce Grove, becoming the first resident lord since Box. In 1906 he surrendered his rights over Nettlebed Common, effectively causing the lordship to lapse. Fleming was succeeded by his son Philip, who in the late 1930s gifted the entire Nettlebed estate (then 2,000 a.) to his nephew (Robert) Peter Fleming (d. 1971). (fn. 112) The estate remained in the Fleming family in 2015.

A separate freehold at Joyce Grove (33 a. in 1840) was incorporated into the manor in 1895, together with an evidently substantial house. (fn. 113) Earlier owners included James Thompson of Wallingford, who acquired it in 1637, (fn. 114) and in the early 18th century (when it belonged to John Toovey) it was a farm called 'Russels house and close', which owed quitrent to the Stonors. (fn. 115) John was succeeded by Thomas Toovey (1766–1849) and his descendants, (fn. 116) and the estate was later occupied by various minor gentry until its sale to Gardiner. (fn. 117)

Manor Houses

John de Mandeville had a manorial curia and garden in 1275, (fn. 118) and in 1520 the king leased the 'site' of the manor (held separately from the demesne) to one of his servants. (fn. 119) It subsequently passed to the Stonors, whose 'manor house' at Nettlebed was mentioned in 1675. (fn. 120) Probably that was the later Nettlebed or Manor Farm, which lies next to the church on the south side of the Henley-Oxford road, and in the 1720s was the farmhouse for the Stonors' Nettlebed estate. (fn. 121) In 1894 it was sold with the rest of the Stonor lands, (fn. 122) but was separated from the Fleming estate in 1973 when it was sold with 5 acres. (fn. 123)

Manor Farm and its former farmyard, from the east.

The present double-pile house was built probably in the late 17th or early 18th century, and retains some 18th-century features. Two-storeyed with attics, and incorporating flint, red brick dressings, and a hipped tiled roof, it has a lobby-entrance plan built around a central brick stack The main five-bay range has modern mullion and transom windows to the ground floor and two-light casements above, while a band of brick separates the two storeys. One of two blocked openings at the rear was probably an oven. (fn. 124) In 1894 the house was surrounded by barns, stables, and other outbuildings, (fn. 125) and by the 1960s it was badly run down, with most of the front windows blocked and a ground-floor bay window added. (fn. 126) Thereafter it was restored and refenestrated.

Another building owned by the Stonors in 1725 stood next to the pottery kilns in the village centre, and was also known as the Manor House. (fn. 127) That was probably the house owned and occupied by Thomas Box in the early 17th century, which seems to have originated as a medieval cottage-holding known as the Lodge; if so, it was presumably associated with the nearby park. Box enlarged it in connection with his farming operations, (fn. 128) but by 1840 it was divided among five separate households, and in the late 19th century it was rebuilt as a single residence. (fn. 129) Of grey brick with red brick dressings, it was still called Manor House in the 20th century, (fn. 130) though after Box's death in 1610 it was no longer associated with the lordship.

Joyce Grove The large Jacobean-style mansion house at Joyce Grove was built for Robert Fleming in 1904–5 on the site of an earlier building, shortly after his acquisition of the Nettlebed estate. Built of red brick with Bath stone dressings and stone-slate roofs, it was designed by the architect C.E. Mallows (1864–1915) of Bedford and London, and enlarged after a fire in 1913. It was not, however, much liked by Fleming's descendants, and in 1940 was given to St Mary's hospital in Paddington as a convalescent home. The hospital later sold it to the Sue Ryder Charity. Two-storeyed with attics and highly irregular in plan, the house features a multiplicity of shaped gables, transomed and mullioned stone windows, and brick and stone chimney stacks, and has a balustraded parapet to the roof. The 13-bay east front includes two off-centre stone porches, the more ornate (on the right) giving access to the hall. An extensive service wing extends westwards from the main ranges south-west corner, while the interior retains good-quality Louis XV and Jacobean-style panelling and some large stone fireplaces. (fn. 131) Mallows also designed the entrance gates to High Street, and a lodge in Beaux Arts style on the Reading road. (fn. 132)

Joyce Grove in 1978, showing the west (garden) front.

The houses predecessor may have existed by 1665, when the hearth tax assessment listed several large houses in the parish. (fn. 133) A map of 1725 shows a three-gabled building, (fn. 134) which may have been rebuilt or remodelled following Thomas Toovey's death in 1849. (fn. 135) In the 1890s it was an 'old red brick mansion with modern additions', with a three-storeyed symmetrical front and prominent end-stacks. (fn. 136)

SOUNDESS 'MANOR'

Soundess manor, so-called from the 16th century, originated probably as a medieval freehold belonging to the Soundy family, who were locally established by the 1240s-50s. (fn. 137) In 1306 John Soundy was the parish's largest taxpayer, but in the later 14th century the estate was acquired by Dorchester abbey, which retained it until the Dissolution. (fn. 138)

In 1545 Richard Taverner bought Soundess from the Crown. (fn. 139) The family lived initially at Woodeaton (sold in 1604), but moved later to Soundess, which passed from Richard's fourth son Edmund (d. 1615) to his son John (d. 1674), to John's daughter Mary Harris (d. 1714), and to her son Taverner Harris (d. 1685). (fn. 140) John Wallis (d. 1717) acquired it through marriage, and was succeeded by his son John (d. 1754) and grandson Taverner (d. 1782), (fn. 141) who c.1755 sold it to Sambrooke Freeman (d. 1782) of Fawley Court (Bucks.). (fn. 142) In 1788 Sambrooke's successor sold the house and 633 a. (in Nettlebed and Bix) to the farmer John Sarney (d. 1796), whose descendants remained at Soundess until the 1850s. (fn. 143) Manorial rights were retained by the Freemans, who in 1853 sold them to C.E. Ruck Keene of Swyncombe. (fn. 144)

Both house and land were sold by Edward Sarney to E.D. Lyon in 1858, passing later to the Freemans' successor at Fawley Court, Edward Mackenzie (d. 1880). (fn. 145) In 1926 his son W.D. Mackenzie sold the then 1,350-a. estate to A.A. Dale, who retained it in 1941. (fn. 146) In the 1960S-70S it belonged briefly to one of the Fleming family, and in the early 21st century was bought by Captain Hon. Robert Yerburgh, son of the 2nd Baron Alvingham of Bix Hall. (fn. 147)

Soundess House In 1665 John Taverner was taxed on 12 hearths at Soundess, the highest assessment in the parish. (fn. 148) A bower in the garden was named after Charles Us mistress Nell Gwynne, who reputedly stayed there. (fn. 149) No other houses at Soundess were mentioned, and probably the remaining settlement was cleared when the mansion house was built. (fn. 150)

By the 1830S-40S the house was surrounded by farm buildings, (fn. 151) but after the construction of a separate Soundess Farm (by 1871) it was rebuilt as a gentleman's residence, and apparently enlarged in the early 20th century. (fn. 152) Later rebuildings (fn. 153) resulted by 2011 in a substantial irregular house of brick and mock timber-framing, with sweeping tiled roofs, tall brick chimney stacks, and multiple dormers above its two main storeys.

LESSER FREEHOLDS

Additional freeholds may have been created by the Crown before Nettlebeds separation from Benson, and included a few acquired by religious houses. Rewley abbey obtained land from Thomas Costard and Thomas Whale in 1303, which it retained (unlike the main Nettlebed manor) until the Dissolution, when its Nettlebed possessions passed to the Butler family. (fn. 154) Dorchester abbey acquired lands in Nettlebed and elsewhere from Sir John Stonor in 1317 in exchange for lands in Pyrton, (fn. 155) and in 1323 and 1338 received additional lands from the Veysyn family and others. (fn. 156) Presumably those were absorbed into its manors of Soundess and Huntercombe, which it also retained until the Dissolution. (fn. 157) Secular freeholders included Peter de Stanford (d. 1252), a clerk of the king's chapel, whose yardland in the parish passed to his brother Oliver. (fn. 158) John James (d. 1396) of Wallingford owned 40 a. of land and wood in Nettlebed and Bix, (fn. 159) Richard English (d. 1460) held a house and 16 a., (fn. 160) and William Stonor (d. 1494) held seven houses and gardens and 6 a. of meadow, which passed to his son and were presumably later absorbed into the Stonors' Nettlebed manor. (fn. 161)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century Nettlebed's economy combined industry, agriculture, and trade. Brick and tile-making and pottery production were undertaken on a considerable scale, employing specialized craftsmen and labourers and numerous part-time agricultural workers. Sheep-and-corn husbandry, and later dairying and pig breeding, were widely practised by tenant farmers, while landowners kept in hand valuable reserves of timber and wood. The villages position on the main Oxford-Henley road added a further element, with numerous inns, shops, and other services catering for visitors' needs as well as for the resident population. In addition the village served as a focus for surrounding parishes, reflecting its roughly central location between Henley, Wallingford, Watlington, and Reading.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 75)

From the Middle Ages Nettlebed's agricultural landscape was typical of the Oxfordshire Chilterns: predominantly arable, but with extensive commons and significant areas of woodland. Any open fields were inclosed at an early date: even in the 13th century a plot (placea) next to 'Piknotesfeld' was defined 'according to its metes and bounds', and by the 15th century most farmland probably lay in small hedged closes. (fn. 162) The arable occupied the lighter chalk and clay-with-flints soils to the west of the village and around Soundess, which were separated from each other by the commons and woods on the higher ground around Windmill Hill. (fn. 163)

In the mid 19th century around two thirds of the parish's cultivable land was arable, with the remaining third divided roughly equally between grass (including commons) and woodland. (fn. 164) Land use fluctuated, however: 18th-century maps show more woodland than later, while in the Middle Ages Rewley abbey's deer parks (called Highmoor) both extended into the parish. (fn. 165) Meadow was always in short supply owing to lack of running water, although some inhabitants cultivated small parcels. (fn. 166) Rights of common pasture were jealously guarded, and concern was sometimes expressed that the sandy heaths of Nettlebed Common were over-grazed. (fn. 167) In the 20th century agricultural and industrial decline enabled woodland to regenerate. (fn. 168)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

During the Middle Ages Nettlebed's inhabitants presumably practised the mixed farming characteristic of the area: surplus crops and wood found a ready market at Henley, and typical livestock included cattle, horses, pigs, and sheep. (fn. 169) From the 11th to the late 13th century the parish was managed as part of Benson manor, which appointed a Nettlebed forester. (fn. 170) Thereafter Nettlebed's non-resident lords generally leased their demesnes and collected rents from their free and customary tenants, while probably also keeping their woods in hand. (fn. 171)

Varying land values may have reflected different farming practices as well as differing soils. In 1252 Peter de Stanford's free yardland (30–40 a.), held for 8s. rent, yielded £4 or 21d.-28d. an acre, suggesting intensive cultivation possibly of hay. (fn. 172) By contrast John de Mandeville held 180 a. of demesne arable worth only 3d. an acre in 1275, with wood pasture worth 25. a year, while his manorial curia and garden were valued at 4s., and tenants' rents and services at £2 1s. 3d. When leased, the demesne's annual value was a modest 8 marks (£5 6s. 8d.). Mandeville's main landholdings lay elsewhere, and possibly he chose not to invest much capital in the management of his Oxfordshire manor. (fn. 173)

Profits fell further after the Black Death. In 1353 the manor was still worth £9 3s. 2d. a year, (fn. 174) but in 1363 the demesne lay untilled, and the Black Prince ordered that it be leased 'as profitably as possible', either for life or a term of years. Timber from abandoned houses was sold, and the tiles re-used at Wallingford castle. (fn. 175) Two years later wood from the manor was felled for sale, and as land values slumped the Prince reduced the rent for John James's freehold from 11s. 11d. to 6s. a year. (fn. 176) The Prince's widow Joan received £3 13s. 4d. from the manor in 1376–7, and Sir John Salisbury collected £3 2s. 4d. in the six months before his arrest in 1387, (fn. 177) while on its reversion to the Crown the manor was valued at £3 6s. 8d. a year. (fn. 178) A carucate (c.120 a.) held by Dorchester abbey was worth only 265. a year (c.2½d. per acre) in 1401, and by 1485–6 the lord's demesne lessee paid only £1 13s. 4d. (fn. 179) As earlier such low returns may in part reflect neglect by absentee lords, and whatever the case the manor's tenants presumably benefited from falling land prices.

Tenant agriculture was varied. Cattle, sheep, wood, and cereal crops (including barley for malting) were staples of the local economy, both for farmers' own subsistence and for sale at Henley, to the parish's brewers, and (presumably) to the brickmakers of Crocker End. (fn. 180) Occupational surnames included 'Shepherd' and 'at Orchard', (fn. 181) while tenants' obligations included fencing Rewley abbey's parks. Nevertheless in 1322 several local men were involved in damage to the abbot's property, including illegal felling of timber. (fn. 182) Woodland was often coppiced, Dorchester abbey reporting in 1401 that its wood was felled every ten years, presumably for fuel. (fn. 183)

Fifteenth-century tenants owed rents for crofts, groves, and named plots of land including Coopers, Egham, and Oakley, suggesting that the inclosed landscape of hedged fields and coppices shown on 18th-century maps was already in place. Formerly separate holdings were consolidated by prosperous freeholders including Edmund Rede (d. 1489) of Boarstall (Bucks.), William English, and Thomas Hay, who presumably sold surplus produce at local markets. (fn. 184) Some farmers also engaged in industry, the yeoman and potter John Lawrence taking a seven-year lease of the 'tile house' in 1480 for an annual rent of 125. and a day's service at harvest. (fn. 185)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

During the 16th century manorial profits began to recover in line with rising prices and population. In 1520 the royal servant Roger Whitton agreed to a rent increase of 3s. 4d. for the site of Nettlebed manor and land in Watlington, while the Crown undertook to provide timber and underwood for repair of cottages and fences, perhaps reversing former neglect. (fn. 186) By 1546–8 the demesne was leased for £2 3s. 4d. a year, rents from free tenants totalling £1 17s. 9d., and customary rents £1 6s. 8d., an over-all increase of 5s. 11d. since 1539. (fn. 187) At Soundess, Dorchester abbey received £5 16s. 11d. rent from 14 free and customary tenants in 1537. (fn. 188) Wood sales provided additional income: coppice wood from Rewley abbeys lands was sold annually, while the Crowns woods were managed by the bailiff of Watlington as in the late 15th century (fn. 189) Nevertheless most rents fell below market values. Copyholders of Marsh Baldon manor occupied several holdings in Nettlebed (some with barns or other buildings) for rents averaging 10s. 6d. a yardland, low enough for at least one tenant to profit by subletting. (fn. 190) Profits were also reduced by occasional wood thefts, as in 1517 when William Butcher stole 2s.-worth of underwood belonging to the lord of Marsh Baldon. (fn. 191)

The parish had the usual hierarchy of yeomen, husbandmen, and labourers, although many inhabitants also engaged in crafts and trades. Six inhabitants assessed in 1543 on goods worth £10-£20 included William Butler (d. 1560), a potter from a long-standing Crocker End family; his relative Thomas (d. 1596) was a yeoman farmer, however, while later family members included a husbandman, carpenter, maltster, and bricklayer. (fn. 192) Seven taxpayers assessed on goods worth £3-£6 may have included less wealthy husbandmen and part-time farmers similarly engaged in trade, while six others with goods worth £1-£2 were possibly small-holding commoners and labourers. (fn. 193) Among the latter class Saunder Cocke, a Crocker End day labourer, left goods worth £12 5s. 4d. in 1609, including grain, wool, sheep, tools for felling wood, and some modest household possessions. (fn. 194) Over all, around half the parish's surviving 16th- and 17th-century wills represent those engaged primarily in farming (yeomen, husbandmen, and labourers), the rest representing craftsmen and tradesmen. (fn. 195)

Farming practice remained typical of the Oxfordshire Chilterns. (fn. 196) Thomas Butler (d. 1596), who probably held former Rewley abbey land, was primarily an arable farmer, leaving £15-worth of grain and four ploughhorses together with plough-gear, carts, and harrows. His few cattle, sheep, and pigs presumably provided milk, meat, and wool, but a more lucrative activity was probably wood cutting, represented by £8-worth of billet and faggots for fuel, and some planks, boards, slats, and posts. (fn. 197) Other early 17th-century farmers pursued similar practices, while a few also grew hemp, hops, and vetches, and made beer, butter, cheese, and bacon. (fn. 198)

The only resident landowner was Thomas Box (d. 1610), whose house (a former cottage-holding called the Lodge) lay close to the then surviving 'North' and 'South' parks, having perhaps originated as a residence for Rewley abbey's park-keeper. (fn. 199) Both parks were enclosed with great ditches' as in the Middle Ages, and were still held in severalty. Box enlarged the Lodge with barns, stables, orchards and a garden, and reportedly built houses on the common for his tenants; certainly he kept cattle, sheep, and pigs there, and was accused by inhabitants of overgrazing, inclosing without consent, and inhibiting their common rights. (fn. 200) One of his main activities was probably selling wood in Henley and London: in 1591 he bought 60 a. in the South park from Evan Arden of Henley, and in 1603 sold wood from adjoining land in Rotherfield Greys and Bix to two Londoners. (fn. 201) The Stonors pursued similar policies following their acquisition of the manor, and in the late 17th and 18th centuries wood from Nettlebed was sold in significant quantities, some of it through their Henley wharf. (fn. 202)

The Stonors' principal property was Nettlebed farm, a group of contiguous closes derived probably from the medieval demesne, and covering c.300 a. in the south-west of the parish. (fn. 203) In the late 17th century it was let for £75 a year, and in the early 18th (to Richard Wade) for £81 7s. 6d. (fn. 204) Joseph Clark, the tenant in the 1780s, continued the parish's traditional mixed farming, maintaining barns, granaries, and stables together with a cowhouse, pigsty, and woodhouse, and pursuing dairying including cheese-making. (fn. 205) The other large farm was Soundess, where the Sarneys grew wheat, barley, oats, and peas, and maintained a brewhouse. (fn. 206) In all a total of 13 Nettlebed yeomen left wills in the 18th century, (fn. 207) and in 1730 agricultural improvements (including use of manure) were said to have successfully improved yields of corn and grass. (fn. 208) A hiring fair was established in 1754, and a livestock fair in 1773. (fn. 209)

Alongside the larger farmers were some lesser tenants occupying small parcels of inclosed arable called 'lands'. (fn. 210) Others probably held only a cottage and garden, grazing livestock and gathering wood on the commons, (fn. 211) while many worked as hired labourers. One in 1694 was accused of sheep stealing, (fn. 212) and by the end of the period poverty was a serious concern. (fn. 213)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

Nettlebed farm and Soundess remained the parish's largest farms in the 19th century. At Soundess Edward Sarney made improvements in the early 1800s, extending the arable, planting swedes as cheap fodder for sheep, and experimenting with different types of fertilizer. (fn. 214) The family continued there as owner-occupiers until the 1850s, farming c.320 a. within the parish and a further 230 a. outside, and employing 25 labourers in 1851. (fn. 215) Sheep-and-corn husbandry was continued by their successors in 1861, supplemented by a few dairy cattle and pigs. (fn. 216)

On the Stonors' Nettlebed farm (310 a.) the Glasspools employed up to 17 farm hands between the 1850s and mid 1870s, when around a third of Nettlebed's households remained directly dependent on farm work chiefly as agricultural labourers. (fn. 217) In 1862 the Glasspools' rent was £387 10s., and the lease included rigorous terms and conditions. (fn. 218) Smaller landowners included Thomas Toovey at Joyce Grove (33 a.) and the lord of a 150-a. Nuffield estate, while several smallholders (mostly occupying 20 a. or less) combined farming with other occupations. (fn. 219) The Stonors exploited much of the parish's woodland directly, felling timber and large quantities of beech poles or other underwood for sale. (fn. 220)

In 1842 the parish was around two thirds arable, with a standard four-course rotation of wheat, barley, turnips, and clover. Farming was considered to be of a 'high and superior character', although the sheep pasture was generally poor. (fn. 221) Wheat, barley, oats, and turnips remained the principal crops in the 1870s, when almost 690 a. were cultivated, and c.300 a. of pasture provided grazing for horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs. By 1880, however, numbers of dairy cattle had increased by a quarter and the sheep flock had more than doubled, as Nettlebed's farmers (like those elsewhere in the region) responded to agricultural depression by shifting to livestock husbandry. (fn. 222) Despite such difficulties farming remained the parish's single largest occupation in 1891, providing employment for around a quarter of those in work. (fn. 223) Seventeen allotments on the village's western edge (mostly of less than ¼ a.) provided additional resources for landless labourers or craftsmen. (fn. 224)

The Glasspools continued at Nettlebed farm until the early 20th century, their rent reduced by 1894 to only £208. (fn. 225) Soundess was leased to a succession of tenants, who employed progressively fewer workers as the farm's acreage shrank. (fn. 226) On both farms oats, turnips, and other fodder crops increasingly replaced wheat and barley, while the area under grass expanded to support dairy cattle, sheep, and a few pigs. The number of regular farm workers fell to just twelve by 1930. (fn. 227)

In 1941 Soundess was run on 'sound lines' by its owner-occupier A.A. Dale, who employed five workers and owned two tractors. Wheat and barley occupied three fifths of the farm's 74 a. of arable, with a further 139 a. grazed by a herd of almost 60 cattle reared on the farm, and by a similar number of sheep. Over 260 pigs were also kept. The larger Nettlebed farm (347 a.) employed eleven workers, growing wheat and oats and running a substantial dairy herd and sheep flock. The farm was well managed, using fertilizers to produce good corn crops'. (fn. 228)

Similar farming continued after the war, with two fifths of the cultivable area (205 a.) cropped with barley, oats, and wheat in 1960, and over 290 a. laid down to grass. Cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry were managed by a small labour force of seven. Three farms occupied a similar over-all acreage in 1970, when one was mostly dairy, another specialized in pigs and poultry, and the third was a part-time smallholding. The last tenant of Manor (formerly Nettlebed) farm left in 1970, and by 1980 only 65 a. were cultivated from within the parish. Land formerly belonging to Manor farm and Soundess nevertheless remained in use, worked as part of larger estates based in neighbouring parishes. (fn. 229)

TRADES, CRAFTS, SHOPS, AND INNS

Nettlebed's position on a major long-distance route, centrally placed amongst surrounding market towns, led to its emergence as a small-scale trade and service centre for a wider area, certainly by the 17th and 18th centuries and probably during the Middle Ages. Woodland crafts and the important brick and pottery industry added to its diversity. Some of the craftsmen recorded on Benson manor in the 13th century possibly lived at Nettlebed, (fn. 230) and by the late 14th century, despite the parish's low ranking in early 14th-century taxation lists, (fn. 231) brick and pottery manufacture was well established (below). An equally prominent trade was brewing: in 1296–7 seven Nettlebed brewers (a large number for so small a place) were presented at Benson manor court, (fn. 232) suggesting passing roadside trade, while the surname Hostiler (recorded in 1440) may indicate an early inn. (fn. 233) One called the George was certainly functioning by 1500, when the tenant threatened to destroy it perhaps in a dispute over rents. (fn. 234) Lesser beersellers probably also served the fluctuating population of brick and tile-makers around Crocker End. More standard rural craftsmen included a Nettlebed smith selling locks to the Stonor family in 1477. (fn. 235)

Brewing continued in the 16th century, (fn. 236) other 17th-and 18th-century tradesmen including blacksmiths, butchers, tailors, cordwainers, carpenters, bricklayers, colliers or charcoal-makers, and a wheelwright. (fn. 237) A few (like the brickmaker Thomas Willis in 1627) were also involved in farming, (fn. 238) although in 1607 an impoverished basketmaker left only £8-worth of modest household goods and the remaining term on his cottage lease. (fn. 239) The largest-scale businesses remained the village's inns, of which the Lion was named in the mid 16th century and the Bull (owned by the Stonors) from the 17th, when it was temporarily sequestered for payment of recusancy fines. (fn. 240) Both David Gascoigne at the Bull and Timothy Holding at the White Hart (taxed respectively on ten and five hearths) issued trade tokens, (fn. 241) while John Meade's inn in 1684 included several heated chambers all with their own names. (fn. 242) Coaching's 18th-century expansion was reflected in the Bull's large-scale remodelling (fn. 243) and in the appearance of new inns including the Nag's Head and the Peacock, whose keeper John Holding operated a post-chaise service. Even so most inns changed hands with some frequency (fn. 244) Specialized grocers were recorded from the 1720s, perhaps also catering partly for travellers as well as for the surrounding area, while one in 1797 had London connections and belonged to a London benefit society (fn. 245)

In 1811, two fifths of families were chiefly employed in trade, manufactures or handicraft, and by 1831 the number exceeded those relying mainly on agriculture. (fn. 246) Coaching collapsed soon after, (fn. 247) but six pubs (including former inns) continued in 1851, along with bakers, butchers, shoemakers, and wheelwrights, while several women worked as dressmakers and laundresses. (fn. 248) A saw mill for cutting brush boards was 'recently built' in 1847, and by the later 19th century woodworkers such as sawyers and chair turners were relatively numerous. (fn. 249) In 1891 around three quarters of workers were employed in non-agricultural occupations, of whom about a third were in domestic service, a third sold everyday goods and manufactures, and another third specialized in woodland crafts, brickmaking, and pottery production. (fn. 250)

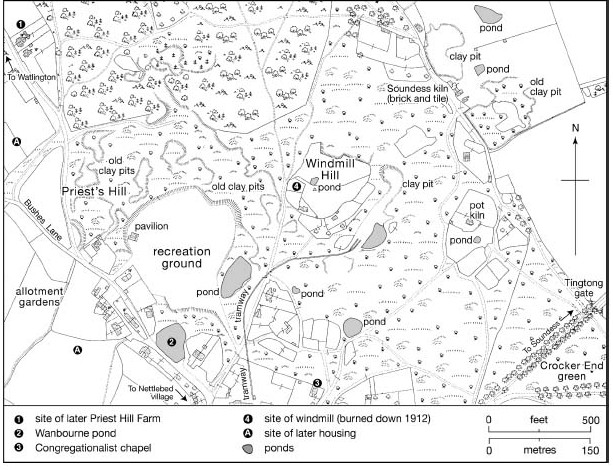

Brick and pottery workings on Nettlebed common in 1918, showing the tramway running to the Nettlebed Pottery near the village (to the south). The recreation ground was laid out by Robert Fleming c. 1904–5 in a heavily quarried area.

During the 20th century the village gradually became more residential and less commercial, as access to shops in Henley and Reading improved. Before the Second World War at least 20 local businesses remained, including a baker, butcher, grocer, and hairdresser. The village also supported three building firms, two motor-car garages, a bank, a doctor's surgery, and several pubs. (fn. 251) In the 1950s small shops and business premises were still said to 'flourish with wide rural support', but as car use increased many closed down. In 2011 most remaining businesses were located on High Street, including the White Hart, a village shop and post office, a cafe and delicatessen, a reproduction furniture business, and a petrol station and motor garage. Some outbuildings at Manor Farm were converted into offices. (fn. 252)

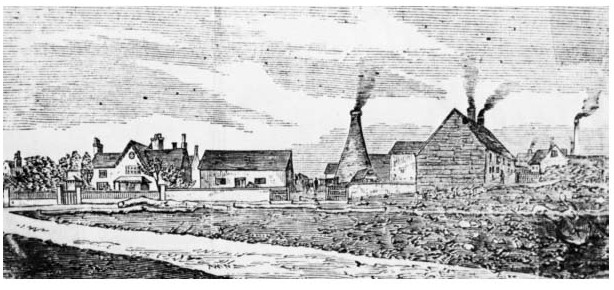

BRICK AND TILE-MAKING

Brick and tile manufacture was presumably encouraged by easy availability of clay, sand, and wood, the lack of good building stone, and local demand from high-status landowners including the Stonors and the Crown. In 1365 Nettlebed kilns supplied some 36,000 tiles to Wallingford castle, and in the early 15th century tiles were sent to building works at Abingdon abbey and Great Milton, (fn. 253) while in 1416–17 Thomas Stonor bought 200,000 bricks from a kiln at Crocker End for work at Stonor Park. In England this was still a new technology, and highly-skilled Flemings may have been hired as overseers. (fn. 254) Three tilers or brickmakers (tegulatores) paid 205. for permission to dig clay (and sand) at Nettlebed in 1485–6, and similar licenses bought by freeholders such as Thomas Hay and Benedict Wheeler suggest that they, too, were involved in the industry (fn. 255)

Nettlebed Pottery c. 1900–10, looking north from the Henley road.

From the early 17th century local brickmakers were mentioned regularly, among them the Sarneys of Rotherfield Greys. Robert Sarney (d. 1667) had a house and kiln at Nettlebed, leased from the Stonors with the right to dig clay and chalk on the common, and the family was probably typical in combining brickmaking with farming. (fn. 256) Three kilns are shown on a map of the Stonor estate in 1725: one by the church belonged to the 'kilnman John Shurfield (d. 1722), while two others (at the junction of the Henley and Watlington roads) were held by William Percy and Thomas Wood. Other kilns stood probably at Crocker End and Soundess. (fn. 257) Bricks from Nettlebed were renowned for their strength, which was attributed to the quality of the clay. (fn. 258)

During the 19th century the Nettlebed industry expanded. Eight brick- and tile-makers were mentioned in 1841, some holding plots on the common which were used for digging sand and clay. (fn. 259) By 1851 the number of operators had doubled, and William Thompsons 'Nettlebed Pottery' employed 30 men and 25 boys. (fn. 260) At Soundess Farm 100,000 bricks were ready for sale in 1861, (fn. 261) and a similar number of bricks and substantial quantities of lime were made annually for the Stonors. (fn. 262) By then clay pits covered large parts of the common around Windmill Hill, from which Thompson laid a tramway to his kilns in the centre of the village. (fn. 263) Control over the digging of sand and clay was sold with the Stonors' estate in 1894, (fn. 264) although by then brickmaking had begun to decline, probably through increased competition. Even so many thousands of bricks were still sent to towns such as Reading and Maidenhead in the early 20th century. (fn. 265) Brick production at Nettlebed finally ended in 1938, and only a single large kiln (just north of High Street) has been preserved. (fn. 266)

POTTERY-MAKING

Pottery manufacture probably took place alongside brick and tile-making, being reliant on similar materials. The industry apparently flourished in the 14th and 15th centuries, when a kiln operated on the Swyncombe boundary, although in 1485–6 Richard Newmer was unable to pay all of his rent for digging clay and sand on the common, (fn. 267) while the potter John Lawrence was accused of failing to maintain his 'tile house' as required by his lease. (fn. 268) By contrast the potter William Butler (d. 1560) was among the parish's wealthiest taxpayers in 1543. (fn. 269)

Thereafter there is little specific evidence of the industry, although as potters and brickmakers often used the same kilns the occupations may have sometimes been combined. A potter was gaoled in 1789 for setting fire to a building in the village, (fn. 270) and in the 19th century the Thompsons' Nettlebed Pottery and the 'Pot Kiln at Crocker End both produced pottery as well as bricks. (fn. 271) Thomas Hobbs, potter and brickmaker, employed ten men and two boys in 1851, and in 1891 his successor made red earthenwares. (fn. 272) The kilns continued after the Stonors' estate sale in 1894, but pottery production ceased before the First World War. (fn. 273)

MILLING

A windmill on Windmill Hill existed probably by 1639, (fn. 274) and in 1695 was leased by the Stonors for £12 10s. a year. (fn. 275) In the 19th century it was replaced by an octagonal smock mill with a revolving upper part, which was brought to the site from Watlington; (fn. 276) the Stonors leased it to a succession of millers including (from 1868) Charles Silver, who complained in 1890 that the tramway to the brickworks was damaging traffic to the mill. (fn. 277) In 1894 Silver paid c.£113 a year for the then 10 horse-power mill and adjoining cottage, which were both sold as part of the Stonor estate. (fn. 278) He continued as lessee until shortly before the mill burned down in 1912. (fn. 279)

Nettlebed windmill in 1907.

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

In the 13th and early 14th century Nettlebed supported a small and seemingly impoverished community of free and customary tenants, holding first of Benson manor, and later of the newly created Nettlebed manor or of the parish's various lay and ecclesiastical landowners. (fn. 280) Only seven inhabitants were prosperous enough to pay tax in 1306, of whom the wealthiest was the freeholder John Soundy (of Soundess), paying 3s. 8d. Two others paid 14d. and 18¼d., and four between 5d. and 10d., making Nettlebed one of the poorer parishes in the hundred. (fn. 281) Many inhabitants were presumably ordinary peasant farmers, although the village's location on the main Henley road, combined with its emerging brick and tile industry, probably gave it a special social character. (fn. 282) Two of its taxpayers were apparently incomers from neighbouring Bix and Witheridge Hill, (fn. 283) and offences recorded at the Benson manor court in 1296–7 suggest (besides widespread brewing) the tensions inherent in a community made up partly of migrants and travellers. (fn. 284) The industrial population was probably focused around Crocker End, although settlement generally was dispersed, as later. (fn. 285)

Few freeholders apart from the Soundys appear to have been resident, although the lord John de Mandeville's maintenance of a manor house in 1275 may indicate either occasional visits, or the presence of a resident bailiff or lessee. (fn. 286) The freeholder Peter de Stanford (d. 1252) held office in the king's chapel, while his brother Oliver may have been a chancery clerk, (fn. 287) and later landowners, too, included outsiders such as the Redes of Boarstall (Bucks.). (fn. 288) Members of the Stonor family or their representatives visited the village occasionally, making purchases from local traders. (fn. 289) Earlier, the presence of Rewley abbeys deer parks seems to have caused some ill feeling, a number of local men being accused in the 1320s of burning the abbots buildings in Nettlebed and felling his timber. (fn. 290)

As elsewhere the Black Death initiated a long-term fall in population and creation of larger holdings, (fn. 291) accompanied probably by increased migration. Inns serving traffic on the Henley road became established during the 15th century, (fn. 292) and Nettlebed continued to attract commercial brewers, of whom John Cornish and John Shalden were possibly both outsiders. (fn. 293) The industrial population also included some firmly rooted families, however, the Eghams (who gave their name to a local grove) occurring as tilers in 1398 (when Thomas Egham was accused of inferior workmanship), and as brewers in 1440. (fn. 294) Robert Egham was demesne farmer in 1456–7. (fn. 295)

1500–1800

Tenant farmers, craftsmen, and industrial workers at the kilns continued to make up the bulk of Nettlebed's population in the post-medieval period, with social continuity provided by such long-standing families as the Blackalls (15th-16th centuries), (fn. 296) Goswells (16th-17th centuries), (fn. 297) Butlers (16th-19th centuries), (fn. 298) and Holdings (17th-19th centuries). (fn. 299) In the 1660s three quarters of householders (24 in all) were still taxed on only one or two hearths, with seven of those excused payment on grounds of poverty (fn. 300) Some housing for poor families may have been provided on the commons, (fn. 301) and the poor were often remembered in local wills, while some were buried at the parish's expense. (fn. 302)

As earlier, the parish's wealthiest and most eminent landholders were probably non-resident, among them Sir Adrian Fortescue (husband of Anne Stonor), and the gentlemen John Loveles, John Vemey, and Philip Smith. The last named was assessed in 1581 on goods worth the remarkably large sum of £55, (fn. 303) and was probably the London haberdasher who acquired a lease of Fillets manor in Henley in 1574. (fn. 304) Some such people may have been outsiders investing in the parish's lucrative woodlands. More important locally were the Taverners and their successors at Soundess, who were probably responsible for clearance of the medieval settlement there when Soundess House was built in the early 17th century (fn. 305) The Taverners witnessed local wills and left money to the poor, (fn. 306) while John Taverner was high sheriff of Oxfordshire in 1662, (fn. 307) and his successor Taverner Harris (a 'factious gentleman' and a whig) was MP for Wallingford, dying of smallpox in 1685. (fn. 308) Memorials in the church testify to the family's high standing within the community. (fn. 309) Comparable were the Tooveys at Joyce Grove, whose house was reputedly visited by both William III and Queen Anne, presumably as a convenient stopping-place on the London-Oxford road. (fn. 310)

Less harmonious relations were experienced by the landowner Thomas Box (d. 1610), who in an acrimonious dispute over common rights inclosed land and a pond used by tenants for their water supply, and challenged their right to gather wood for fuel and repairs. The tenants, who included a local yeoman, husbandman, tailor, and two labourers, responded by breaking his fences and impounding his sheep, which he released by force. (fn. 311) Box's claims to the lordship were successfully challenged by the Stonors of Stonor Park, who mostly kept themselves aloof from parish affairs, although their estate was carefully managed. (fn. 312)

Several inns operated during the 16th and 17th centuries, (fn. 313) though not all enjoyed a good reputation. Innkeepers in the 16th century were accused of sheltering vagabonds, serving horse-bread, and making excessive profits, (fn. 314) while in 1627 the sheriff of Oxfordshire, required to lodge Sir Erasmus Dryden at Nettlebed, reported that 'there is no house of any sort fit to receive him in that place, which is one of the meanest villages in the county'. (fn. 315) An innkeeper in 1690 was reported for receiving men of 'bad conversation'. (fn. 316) Conditions had presumably improved by the mid 18th century, when the rector of Nuneham Courtenay regularly dined at Nettlebed's inns on his journeys to and from London. (fn. 317) Other visitors included the German traveller Karl Moritz, who in 1782 (having found Henley 'too fine') lodged comfortably in one of the village's inns, where a party of militia soldiers was 'making merry'. The occupants of a passing post-chaise were met 'with all possible attention', and at church on Sunday Moritz noticed that the parish's farmers dressed 'with some taste, in fine good cloth'. (fn. 318)

Nettlebed's location on a major route also brought less welcome consequences, not least during the Civil War. Royalist forces (accompanied by the king) stayed at Nettlebed for several days in April 1643 following a failed attempt to relieve Reading, and in May Parliamentary forces also lodged in the village, where lime was requisitioned and several soldiers killed or captured. (fn. 319) The following year several Parliamentary commissioners had 'very bad quarter' at Nettlebed, 'which is but a small country village', though they were 'cheerful in their mean quarter and entertainment'. (fn. 320) Soldiers were camped in the parish church, where they damaged memorial stones by lighting fires. (fn. 321) The road also attracted criminal elements: several highway robberies at or near Nettlebed were reported in the mid 18th century, (fn. 322) and though the highwaymen were usually outsiders, some inhabitants also engaged in opportunistic thefts from passers-by (fn. 323)

The parish's social make-up changed little during the 18th century, when the Tooveys at Joyce Grove and the Wallises at Soundess remained its most eminent inhabitants. (fn. 324) John Wallis (d. 1717), a wealthy landowner with friends in London, was a son of the celebrated mathematician and cryptographer John Wallis (d. 1703), who stayed at Soundess in old age and took an interest in local politics. (fn. 325) Later the house and land were leased by the non-resident Freemans as a working farm, tenanted by the prominent Sarney family. (fn. 326) Both the Sarneys and Thomas Toovey engaged in recreational hunting, and during the later 18th century the Stonors and Freemans appointed gamekeepers to control poaching on their estates. (fn. 327) Occasional crimes included sheep-stealing, assault, fraud, and arson, while the mutilated body of a murdered child was found in the parish in 1754. (fn. 328)

Since 1800

In the early 19th century Nettlebed remained a notable stopping-place on the London-Oxford road and a minor commercial centre for surrounding parishes, its population growing from 500 in 1801 to over 600 by 1831, and peaking at 754 twenty years later, when it was one of the hundred's largest villages. (fn. 329) More than half the population were then still native to the parish, with over three quarters born in Oxfordshire; nevertheless Nettlebed continued to attract outsiders, including a West Indian housekeeper, a Leicestershire schoolmistress, and an itinerant cordwainer who had worked in Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, and Liverpool. (fn. 330) The village was also beginning to attract a few wealthier residents and professionals, amongst them the London surgeon William Penlington, who married into a local family. (fn. 331)

In 1813 a maypole stood at the villages eastern edge, while the main street had a 'remarkably clean and neat appearance', its shops and inns giving the air of a 'bustling town'. (fn. 332) The end of coaching in the 1840s presumably had a detrimental effect, although six public houses still served the parish in 1851, of which the White Hart, Cross Keys, Bull, Nag's Head, and Red Lion all lay along High Street. The Rising Sun was on Watlington Street. Most publicans were incomers, though long-settled in the village, the chief exception being George Smeed of the Bull, who was recently arrived from Godalming (Surrey). (fn. 333) The inns provided lodgings for workers, including brickmakers from Ipsden and South Stoke and shoemakers from Maidenhead (Berks.), and like the larger houses created employment for servants. Domestic staff at Soundess were mostly local, although at Joyce Grove the cook was from Suffolk and the footman from Hampshire. (fn. 334)

After 1832 the village served as a polling station venue for county elections. (fn. 335) A petty constable routinely dealt with theft, poaching, and other crimes from across the area, (fn. 336) while offenders were sometimes also prosecuted by village tradesmen. A county police station was opened on Watlington Street in the early 20th century. (fn. 337) The former hiring fair was gradually transformed into an annual pleasure fair held in late October, its stalls attracting numerous visitors, (fn. 338) while in 1871 a small group of gypsy hawkers and musicians encamped presumably on the common. (fn. 339) A short-lived benefit society mentioned in 1848 was followed by others (based at the Red Lion or the Bull) in the 1870s and 1890s, the last of which continued in 1918, (fn. 340) while a cricket club was established c.1870. (fn. 341) A village band was re-formed in 1875, when mummers still visited houses and pubs before Christmas. (fn. 342)

Throughout that period the village became increasingly gentrified: a dozen residents enjoyed a private income by 1901, while the proportion of people in domestic service had doubled from 5 to 10 per cent over the previous fifty years. Less than half the population was then native to the parish, with just under a third drawn from outside the county, including some from Ireland, Canada, and the United States. (fn. 343) Change continued in subsequent decades, the number of residents with private means doubling to 24 by 1935. (fn. 344) Resident gentry over the period included the Mackenzies at Soundess (occupied by W.D. Mackenzie in the early 1890s), and the Flemings (as lords) at the newly built Joyce Grove. (fn. 345)

Robert Fleming (d. 1933) made a considerable contribution to village life, providing a recreation ground on a heavily-quarried part of the common soon after his arrival to replace the former cricket pitch near Joyce Grove. A pavilion was added in 1910, and Fleming continued to support the club financially (fn. 346) More significantly, management of the common was vested by Act of Parliament in a body of conservators charged with keeping it open for the public. (fn. 347) Fleming also built the working men's club or village hall (opened 1913) on High Street, used by a variety of local clubs and societies and showing early educational films, (fn. 348) while his wife paid regular visits to the school, distributing toothbrushes and powder. More controversially Fleming closed down the Red Lion because of noise at closing-time, and tried also to end the October fair. (fn. 349)

Sixteen parishioners were killed in the First World War and at least eleven in the Second, when the parish witnessed the arrival of military personnel, evacuees, and prisoners of war. (fn. 350) The coronation of 1953 was marked by a parade, dancing, and fireworks on Windmill Hill, (fn. 351) while social life in the later 20th century continued to focus on the village hall, sports clubs, shops, and pubs, enlivened by a number of well-known 'local characters'. (fn. 352) The former Red Lion was briefly converted into an art gallery in the late 1960s, (fn. 353) leaving the White Hart as the villages only remaining pub in 2011. The parish continued to attract wealthy incomers including the naval officer J.E. Broome (d. 1985) and the actor George Cole (d. 2015), (fn. 354) although the community remained socially mixed, with c.15 per cent of houses rented from the local authority in 2001. (fn. 355) In 2011 the village supported a doctors surgery, a Women's Institute, and a wide range of local societies and events; the Women's Institute (established for 60 years) closed in 2013, but was replaced by a Friendship Club. (fn. 356)

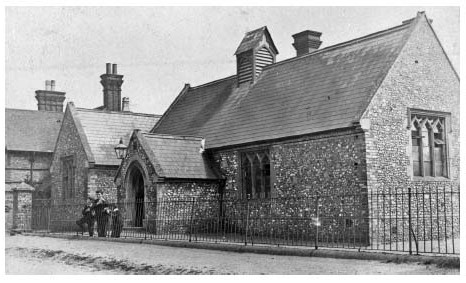

Nettlebed school (built 1846) in 1904, looking south-east.

EDUCATION

A Nonconformist academy at Nettlebed was run by the Independent minister Thomas Cole from 1666 to 1674, while in 1667 the churchwardens reported an unlicensed Anglican teacher. (fn. 357) A schoolmaster was mentioned in 1755, and a girls' boarding school operated from 1760 to 1763. (fn. 358) In 1808 the parish supported two boys' boarding schools and another for girls, a day school, a dame school, and a Sunday school; (fn. 359) all probably continued in 1818, though none was endowed, and the poor were said to lack 'sufficient means of education'. (fn. 360) A ladies' boarding school was mentioned in 1829, and a gentlemen's boarding school in 1830: (fn. 361) the latter was run by Robert Fisher, and by 1841 had expanded to take in 24 boys and 19 girls aged from 6 to 16, instructed by four teachers. Two other teachers also lived in the parish. (fn. 362)

Nettlebed Board (later Primary) School

A day and Sunday school linked to the National Society was built on High Street in 1846, on land donated by Thomas Lewis. Supported by subscriptions, collections, and school pence, it had c.45 pupils in 1867, (fn. 363) and was enlarged in 1872. In 1875–6, however, it was closed at the ratepayers' request and transferred to a School Board, amid rancorous exchanges. (fn. 364) Following further enlargement c.116 boys and girls attended in 1894, when the school received a government grant of c.£90. (fn. 365) Improvements followed under the headmaster Thomas Johnson, who was, however, later accused of improper conduct, and was dismissed in 1915. (fn. 366)

The school benefited from Robert Flemings philanthropy, and in 1927 he provided adjoining land for a new county council school, the old building becoming a church hall. The new school admitted pupils from Nuffield and Bix, and inspectors' reports in the 1930s were generally favourable. (fn. 367) In 1959 the school was reorganized as a primary school, which in 2011 taught 108 mixed pupils aged 4 to 11, the older children attending schools in Henley. In 2005–6 the school was rebuilt to the south of the 1920s building, which was replaced by new housing, while the original school was converted into shops. The new school doubled as a community centre out of school hours. (fn. 368)

CHARITIES AND POOR RELIEF

From the 16th century several of Nettlebed's inhabitants made small cash bequests to the poor, among them the landowners Thomas Box, Taverner Harris, and John Wallis. (fn. 369) Ralph Warcopp (d. 1605), of English in Newnham Murren, left 20 nobles (£6 13s. 4d.) for setting the poor to work with flax, hemp, and wool, to which Robert Butler (d. 1621) added a further 6s. 8d. (fn. 370) The charity was not mentioned later, and no others were endowed until the 19th century, although Nettlebed was among several parishes eligible to nominate candidates for an almshouse at Upper Assendon established by Sir Francis Stonor (d. 1625) in 1620. (fn. 371)

In the late 18th century the cost of poor relief was mostly funded by parish rates, and fell from £150 in 1776 to an average of £112 in 1783–5. (fn. 372) Expenditure increased dramatically (to £305) in 1803, mainly because 245 non-residents received support; otherwise only 47 people (including 20 children) were relieved permanently, and 35 occasionally, in all c.16 per cent of the population. Costs rose further to an average of £438 in 1813–15, when 28 people were relieved permanently and 32 occasionally, c.13 per cent of the population. (fn. 373) Thereafter expenditure fluctuated considerably, increasing from £375 in 1816 to £603 in 1818, then falling to £417 in 1821 and £378 in 1823. The annual average from 1816 to 1824 was c.£463, falling to £398 in 1825–32. In 1834 costs more than halved to £194, after which Nettlebed became part of the newly established Henley Poor Law Union. (fn. 374) Several inhabitants were subsequently admitted to the union workhouse. (fn. 375)

Later charities were established under the wills of James Champion (d. 1860) and Elizabeth Lewis (d. 1867). In the early 20th century Champions produced £2 11s. a year for distribution in bread and 305. for the Sunday school, while Lewis's provided £8 17s. a year for twelve 'deserving' men and women. (fn. 376) Both continued in 1995 as part of the Nettlebed United Charities, which included a third eleemosynary charity set up by John Ward, and were regulated under a revised Charity Commission Scheme of 1973; the United Charities were dissolved in 1996, however. (fn. 377) Registered Nettlebed charities in 2010 included the Nettlebed Medical Surgery Trust (with income of £11,965), a sports association (£49,684), and the friends of Nettlebed school and of a local pre-school. (fn. 378) The Nettlebed School Trust provided grants for people up to 25 years of age. (fn. 379)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

In the Middle Ages Nettlebed was a chapelry of Dorchester, but had its own small endowment (appropriated to Dorchester abbey), and probably functioned as an independent parish, evolving later into a perpetual curacy. From the 13th century the benefice was usually held with Pishill (another chapelry of Dorchester), although the living remained a poor one. The parish remained under the jurisdiction of the peculiar of Dorchester until 1846, and the benefice was formally separated from Pishill in 1853. (fn. 380)

Until the benefice's separation and the building of a vicarage house in 1866, Nettlebed was served mostly by part-time, non-resident chaplains, who rarely remained in the parish for long. Inhabitants complained of the clergy's neglect, and supported and maintained the church in other ways. Roman Catholicism and Protestant Nonconformity were briefly evident in the 17th century, and a Congregationalist chapel was built in 1838. The parish church was rebuilt in 1845–6.

CHURCH ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

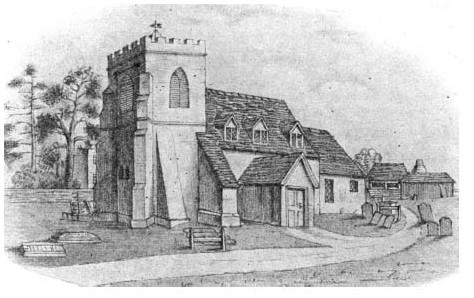

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Nettlebed belonged to the royal manor of Benson, and was probably subject to Benson church. It was still claimed as a chapelry of Benson (with Henley and Warborough) in 1279, but from c.1140–2 its ecclesiastical revenues were appropriated to Dorchester abbey along with Benson's. (fn. 381) A church at Nettlebed probably existed by that date or very soon after: a Norman font and fragments of a 12th-century tower may survive from the medieval building, (fn. 382) which was presumably established by the Crown, by an unknown tenant or feoffee, or by Dorchester abbey.

From the 13th century the churches of Nettlebed and Pishill were valued together, and Dorchester abbey probably appointed a single priest to serve both. (fn. 383) At the Dissolution the combined endowment of Nettlebed and Pishill was sold to a lay impropriator, (fn. 384) and thereafter the living became a donative curacy, developing later into a perpetual curacy served by a 'vicar'. The bishop did not institute to the benefice until the 19th century. (fn. 385) The church's dedication to St Bartholomew is recorded from the early 18th century. (fn. 386)

In other respects Nettlebed seems to have enjoyed full parochial rights, including baptism and burial. (fn. 387) After its separation from Dorchester peculiar it became part of the rural deanery of Cuddesdon (1846–52), and later of Nettlebed (1852–74) and Henley (from 1874). (fn. 388) From 1977 its priest-in-charge also served the benefice of Bix-with-Pishill, and from 1978 that of Highmoor, until in 1981 the three benefices were formally united under a rector based at Nettlebed. Rotherfield Greys was added to the living in 2003, and Nuffield from 2006. (fn. 389)

Advowson, Glebe, and Tithes

Throughout the Middle Ages Nettlebed church remained in the patronage of Dorchester abbey. No formal presentations were made, however, and the benefice was probably served by non-resident secular chaplains, (fn. 390) a wrongful presentation by the king in 1394 being successfully revoked. (fn. 391) After the Dissolution the advowson passed to Roger Hatchman of Ewelme, to the Taverners of Soundess, (fn. 392) and (by 1615) to Francis Stonor (d. 1625), whose family retained it until the early 19th century. (fn. 393) As Roman Catholics the Stonors may, however, have regularly granted the patronage to others, including the University of Oxford, and it is unclear how often they acted as patron themselves. (fn. 394)

In the 19th century the advowson was bought by Nettlebed's incumbent T.L. Bennett (d. 1844) of Highmoor Hall. Thereafter it changed hands frequently and was held (inter alia) by the dowager Lady Farquhar, H.A. Baumgartner (vicar 1881–1908), J.C. Havers of Joyce Grove, and the Church Patronage Trust, which remained a joint patron of the united benefice in the early 21st century. (fn. 395)