Pages 192-234

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

EWELME

The attractive village of Ewelme lies amongst the Chiltern foothills, its celebrated 15th-century almshouses (which incorporate some of the earliest brickwork in Oxfordshire) extending up a hillside to the church. (fn. 1) Further down, the stream from which the place name derives (fn. 2) flows alongside the village street, incorporating watercress beds developed in the 19th century. Resident medieval lords included Geoffrey Chaucer's son Thomas and granddaughter Alice de la Pole, duchess of Suffolk: their elaborate tombs survive in the church, and in the 16th century the de la Poles' substantial manor house (now mostly demolished) became an occasional royal residence. The village has always been predominantly agricultural, however, and its cottages and farmhouses are otherwise characteristic of the area.

PARISH BOUNDARIES

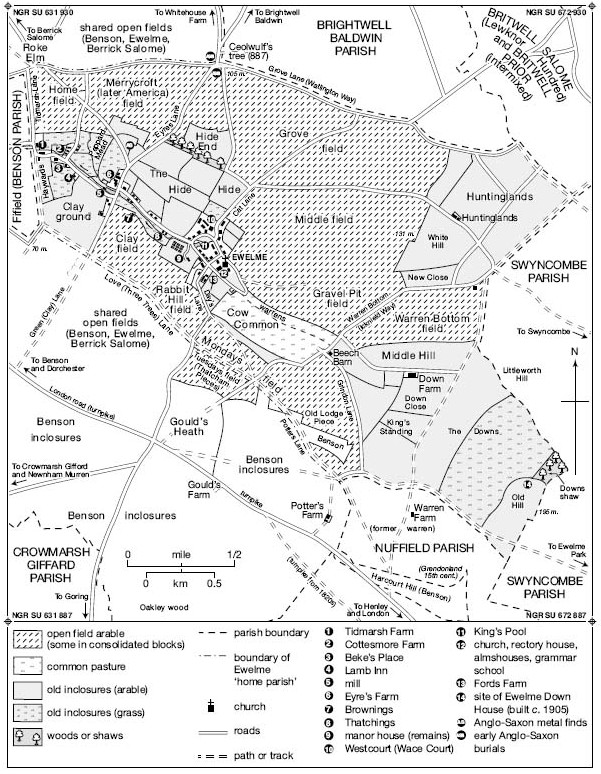

In 1840 Ewelme parish covered 2,376 acres. On the north-west and south-west, where it shared open fields with Benson and Berrick Salome, there was no clear linear boundary until inclosure in 1863, (fn. 3) the parishes' intermingling reflecting their close association with Benson's Anglo-Saxon royal estate (see Fig. 4). (fn. 4) A core area known as the 'home parish' was more sharply defined (Fig. 50), following Grove Lane on the north, Tidmarsh Lane on the west, and Love and Potter's Lanes on the south, while the irregular eastern boundary followed paths or field boundaries to bring in Ewelme Downs in the south-east, and an area known as Huntinglands in the north-east. (fn. 5) The home parish's antiquity is unclear, but its fields were independently administered, and probably it reflected medieval arrangements. (fn. 6)

Some of the boundaries around Huntinglands and the Downs were perhaps adjusted during late medieval inclosure, (fn. 7) and in the 15th century areas known as Heydon and Grendon still straddled the south-eastern boundary, the former extending into Ewelme park in Swyncombe parish, and Grendon into the later Warren farm in Nuffield parish. Both the park and Warren farm became attached to Ewelme manor in the later Middle Ages, but remained outside the parish. (fn. 8) The 19th-century acreage also included 124 a. of former woodland at Westwood near Bix (three miles to the east), and 3 a. of detached riverside meadow in Drayton St Leonard, both of which had probably formed outliers of one of Ewelme's four late Anglo-Saxon estates. Other parish outliers included premises in Benson and Roke, and Whitehouse Farm near Berrick Salome, apparently all reflecting early manorial connections. (fn. 9)

At inclosure the boundaries with Benson and Berrick Salome were redrawn, creating a parish of 2,495 a. which, reflecting earlier complexities, included 226 a. scattered in twelve detached areas. Changes in 1882 reduced it to 2,487 a., while rationalization in 1932 removed the remaining detached parts (including Westwood and premises at Roke) and brought in other areas, reducing the parish to 2,350 acres. (fn. 10) Alterations in 1993 brought in Harcourt Hill and the former Warren farm south of Ewelme Downs, leaving Ewelme with 2,842 a. (1,150 ha.). (fn. 11)

LANDSCAPE

The parish's eastern part - inclosed by the late Middle Ages - rises onto the Chiltern foothills, reaching 131 m. near Huntinglands and 190 m. at Ewelme Downs. Its flatter western part, dominated by open fields until the 1860s, extended towards the Thames floodplain, the home parish's western boundary lying at 65 metres. The village itself occupies a gently descending valley, whose flanking slopes reach over 100 m. to the north and south. (fn. 12) The underlying geology is mostly chalk, though much of the village (including the church and main street) lies on tongues of gravel, (fn. 13) and clay was reflected in early field names, particularly south of the village. (fn. 14) In 1839 the soils were characterized as typical of the area, well suited to sheep-corn husbandry. (fn. 15)

Ewelme 'home parish' c.1800. (For shared fields see Fig. 4 and Plate 7; for Wace wood (detached) see Figs 75 and 103.)

The village pond and roadside stream are fed from springs within the village, and several others formerly rose amongst the Chiltern foothills, occasionally causing flash floods. (fn. 16) Twentieth-century gravel extraction allegedly lessened their flow, reducing available pasture. (fn. 17) The springs' importance is reflected in the villages name, from the Anglo-Saxon aew(i)elm (a spring); (fn. 18) from the Middle Ages, however, the name was frequently corrupted to Newelm, apparently influenced by the presence of numerous elms around the manor house and village. (fn. 19) The pond itself was called Queens (and later Kings) Pool by the 1570s, from association with the nearby royal manor house. (fn. 20)

COMMUNICATIONS

The village lies along one of several roads radiating eastwards from Benson, connecting with Pyrton and Watlington and, further east, with the Chiltern uplands. (fn. 21) The northernmost road (the modern B4009) passes the probable hundredal meeting place, (fn. 22) and was presumably important from an early date. In the 19th century it was called Watlington Way or Grove Lane, and formed part of the parish boundary (fn. 23) South of the village, the lane which formed the home parish's southern edge may mark the course of the Roman road from Dorchester to Henley; (fn. 24) the medieval Henley (and London) road ran further south along Beggarsbush Hill, however, and was turnpiked in 1736. (fn. 25) Intersecting those roads east of Ewelme village is the ancient Icknield Way, which passes along Warren Bottom following the Chiltern scarp. (fn. 26)

The village was linked to the major routes and surrounding settlements by a dense network of roads and lanes, of which many survived inclosure as roads or bridleways. (fn. 27) The most important include the now-metalled Firebrass Hill and Eyres (formerly Mill or Watlington) Lane, both running north-east to Watlington, while the metalled Days or Fords Lane climbs south up a deep hollow way to join the former London road. Surviving tracks include Potters and Grindon Lanes, both running south-east towards former farms, Ewelme park, and the London road, while Rumbold's, Cottesmore, and Tidmarsh (or Roke) Lanes run north towards Whitehouse Farm, Holcombe, and Berrick Salome. (fn. 28) Rumbold's Lane formed part of a late Anglo-Saxon route linking vale and upland, while Cottesmore Lane may be a continuation of a minor Roman road through Newington parish. (fn. 29) The main village street was called the 'London highway' in 1710, (fn. 30) and remained a recommended trunk road until 1969 when, following local protests, traffic was diverted along the present B4009. (fn. 31)

Two carriers were noted in the 1780s, of whom William Bond ran a service through Dorchester to Oxford. (fn. 32) The family continued as carriers (and later publicans) until the 1860s, and their successors the Cherrills in the 1930s. (fn. 33) By then a bus service begun in 1920 ran to Wallingford three times a week. (fn. 34) The nearest railway stations were at Wallingford (opened in 1866) and Watlington (opened 1872), which imported coal and exported watercress and other produce. A Ewelme–Watlington link proposed in 1881 came to nothing, and both stations closed in the 1950S-60S, leaving a station at Cholsey 5 miles away (fn. 35) A post office run by a Ewelme grocer existed by 1847, when letters were delivered through Wallingford; before 1903 it became a money and telegraph office, moving later from premises on the main street to the former Wesleyan chapel. (fn. 36) It closed in 2000 following a change of ownership. (fn. 37) Buses to Wallingford, Benson, and Henley continued in 2015.

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

Prehistoric to Anglo-Saxon Settlement

Isolated finds of Neolithic tools and pottery probably reflect small mobile groups passing between the chalk downlands and Thames floodplain. (fn. 38) No Bronze- or Iron-Age settlement is known, although a circular cropmark south of the village may be prehistoric, and there have been isolated Iron-Age finds. A substantial Romano-British presence seems likely given the terrain, the proximity of the Dorchester-Henley road and Icknield Way, and a large number of Roman finds including pottery, coins, and metalwork, unearthed within the village, west of Eyres Lane, and close to the Roman road. (fn. 39) No settlement has yet been discovered, although the presence of coins and (possibly) a votive figurine has prompted speculation that a small shrine may have been associated with local springs. (fn. 40)

A 5th- to 6th-century Anglo-Saxon cemetery was established on high ground north-west of the modern village, adjoining early routeways and the later parish boundary. Significant 8th- and 9th-century metal finds a little further south include 8th-century coins and several pins, strap ends, and hooked tags: their quantity suggests a place of trade or (possibly) tax collection, associated presumably with the adjacent royal centre at Benson, or with the probable hundredal meeting place to the north. Associated settlement may have lain close by on the modern villages western edge. (fn. 41) The area was separated from Benson before the Norman Conquest, perhaps initially as a 20-hide unit, and by 1086 comprised four separate estates each with a manorial centre. (fn. 42) By then there was almost certainly settlement around the modern village, which may have adjoined a late Anglo-Saxon 'hide farm' recalled in the field name 'the Hide'. (fn. 43)

Population from 1086

By 1086 Ewelme's four manors had 46 recorded households, amongst the highest concentrations in the hundred. (fn. 44) During the 12th and 13th centuries the population probably grew: over 80 tenants were noted in 1279, although an unknown number of the freeholders may have lived elsewhere. (fn. 45) Mortality during the Black Death was severe, rents on one manor falling by 59 per cent; (fn. 46) nonetheless in 1377 there were 84 taxpayers aged over 14, making Ewelme the fifth or sixth largest settlement in the hundred. (fn. 47) From the mid 15th century its reduced population was swelled by de la Pole servants and retainers, almsmen, and grammar-school pupils, (fn. 48) and the village apparently maintained its ranking in the 16th century: (fn. 49) by then numbers were probably rising again, fuelled partly by immigration. (fn. 50) In 1662 there were at least 38 houses, and 150 'conformists' (probably adult men and women) were noted in 1676. (fn. 51) Over 70 families were reported in 1738, and c.65 houses (some in multiple occupation) in the 1760s–80s. (fn. 52) By 1801, 86 houses accommodated a population of 490, comprising 99 familes. (fn. 53)

The population continued to grow during the 1810s– 40s and (more slowly) in the 1850s–60s, reaching 691 (in 154 houses) by 1871. Thereafter agricultural depression prompted a fall to 473 by 1901 and to 426 by 1921. A small increase in the 1930s was followed by more sustained growth after the Second World War, accelerated by new house-building: a population of 471 in 1951 grew to 810 in 1971 and to 1,103 in 2001, the number of dwellings rising from 154 to 422. Presumably that figure included some RAF housing on the parish's southern fringe, adjoining RAF Benson. In 2011 the population was 1,048, comprising 387 households in 410 houses. (fn. 54)

Village Development

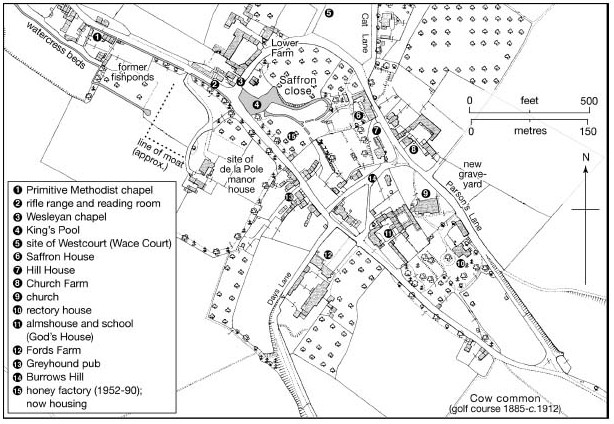

The village's elongated, polyfocal layout (Figs 50–2) was probably established by the 13th century. The church (founded by the 1180s and probably much earlier) (fn. 55) stands partway up the hillside on the northern edge of what may once have been a long linear green or enclosure, now bounded by Parson's Lane and by the village street in the valley bottom. (fn. 56) A substantial wall excavated south-west of the church may mark one of the early manor houses, and another (Wace Court or Westcourt) stood immediately north-west of Parson's Lane. A third perhaps stood south of the main street, on the site of the de la Poles' 15th-century successor. (fn. 57) Pottery finds suggest 13th- and 14th-century occupation across that area and along the village street at Brownings. (fn. 58) Further west, medieval settlement extended along the Fifield road perhaps as far as Tidmarsh Lane, encompassing late medieval homesteads at Cottesmore Farm, Beke's Place, and near the mill. (fn. 59) Outlying farmsteads on the eastern downlands are suggested by the 13th-century surnames 'of Heydon' and 'of Grendon', although none seem to have survived into the late Middle Ages. (fn. 60)

Ewelme village from the south-west c.1880, showing the church and grammar school (centre right), Fords Farm with its roadside barns along Days Lane (bottom right), and Church Farm and its barns (top left at the top of the hill).

Ewelme village and the former manorial site in 1910.

Those farms apart, late medieval depopulation (fn. 61) probably affected the density rather than the overall layout of settlement. During the 1430s–40s the de la Poles replaced buildings below the church with the brick-built almshouses and grammar school, and built or rebuilt the large manorial complex south of the village street. (fn. 62) The rest of the village was unaffected, however, and 18th-century maps confirm that settlement still extended from Tidmarsh Farm to the edge of the cow common, with houses loosely scattered along both sides of the village street and, higher up, along Parsons Lane and Burrows Hill. (fn. 63) The manor house was mostly demolished c.1612, (fn. 64) while a demesne barn near the grammar school was rebuilt as cottages c.1650–82. (fn. 65) A vacant area in Saffron Close (on Parsons Lane opposite Westcourt) resulted from a fire in 1755, which destroyed 13 houses and associated farm buildings. (fn. 66) Early street names included Court or Cat Lane (named from Wace Court) and Burrows Hill (leading up past the church), while Parsons Lane, bordering the rectory house, was formerly the 'upper road'. (fn. 67)

Outlying downland sites included Huntinglands (which had a stone house and barn by 1681) and Down Farm, probably both developed from post-medieval field barns. (fn. 68) A 'warren house' and a nearby old lodge' (near the Nuffield boundary in the south-east) were mentioned in the early 17th century, by which time the lodge had been demolished. Some of its materials were re-used in a nearby lodge at Grendon, perhaps Warren Farm in Nuffield. (fn. 69) Further north, a predecessor of Whitehouse Farm existed by 1681, set amidst the shared open fields. (fn. 70)

Nineteenth- and early 20th-century changes included demolition of Westcourt and the mill, conversion of the stream to watercress beds, (fn. 71) and increasing infill, while an isolated country mansion was built on the Downs c.1905. (fn. 72) Road surfacing transformed the alternately muddy and dusty village streets, (fn. 73) while mains electricity was available from 1932–3, (fn. 74) and mains water and drainage from c.1953, (fn. 75) replacing wells, streams, and ponds at constant risk of pollution. (fn. 76) Further change followed the development of RAF Benson from 1937 and its expansion to the Fifield road in 1942, prompting demolition of the Lamb Inn, Eyre's Farm, and several other buildings. (fn. 77) Large compounds built for service personnel from the 1960s lay mostly south of the parish boundary, however, largely preserving Ewelme's rural setting. A few council houses were built on Green Lane in the 1920s, and more off Cat Lane in the 1940s–50s, followed by small private developments at Chaucer Court (the site of Westcourt) in 1966–8, and east of King's Pool (replacing a vacated honey factory) c. 1992–3. (fn. 78) Over all the number of houses more than doubled between 1961 and 2001, (fn. 79) loss of elms in the 1970s further altering the village's appearance. (fn. 80) The watercress beds, abandoned in 1988, were restored by the Chiltern Society following an appeal launched in 1999. (fn. 81)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Ewelme's best-known buildings are the medieval almshouses, school, and church, together with the largely demolished 15th-century manor house. (fn. 82) Its farmhouses and cottages are more typical of the area, combining timber-framing (much of it in elm), flint, chalk clunch, and (latterly) brick. Those of late medieval or 16th-century origin include Old Mill House, Brownings, and Thatchings, all originally timber-framed. The first incorporates a high-status 3-bayed hall-house of late 15th-century date, which includes raised cruck trusses and was perhaps (like nearby Beke's Place) attached to a substantial medieval freehold. Floored over in the 16th–17th century and later encased in brick, it was extended into a small gentry house c.1890–1900, probably for Edward Birkett or Charles Schunk. (fn. 83) Thatchings, a smaller 3-bayed house of 1½ storeys, has a timber-framed core behind a clunch façade with brick window-dressings, and retains some early thatch smoke-blackened from an open hearth. (fn. 84) The two-storeyed Brownings, the only house south of the village stream, has been partially underbuilt in brick, and has brick infill to the framing and a half3-hipped tile roof. At the rear is a massive chimneystack constructed mostly of clunch, with squared limestone quoins. Nearby Brook Cottage (formerly Smockacre) also retains a probably 16th-century timber-framed core. (fn. 85)

Most houses seem to be 17th-century and later, (fn. 86) the majority walled in clunch or flint with brick dressings. Poor-quality timber-framing continued, however, (fn. 87) while some better façades feature patterning in red and grey brick. (fn. 88) Larger farmhouses include Fords (Plate 9), a substantial rubble and brick house of probably 17th-century origin, which was remodelled for John Lane in the 1780s and extended for the Franklins in the 19th century. (fn. 89) Probably of similar date are Lower and Church Farms on Parsons Lane and the Old Mansion at Cottesmore. (fn. 90) Surviving agricultural buildings reflect the arable-based mixed farming which characterized Ewelme from the Middle Ages. (fn. 91) A barn at Cottesmore has been dendro-dated to 1602, (fn. 92) while the 18th-century farmyard at Fords includes a former granary, stables, and nine-bay aisled barn, all now converted to other uses. (fn. 93) Two large rubble-and-brick barns formerly belonging to Westcourt are of similar date. (fn. 94) All are tiled, although thatched farm buildings were formerly common. (fn. 95) Numerous labourers' dwellings include the thatched, 1½-storey King's Pool Cottage at the bottom of Parson's Lane, enlarged by a farmer in the 1780s and let to a carrier. (fn. 96)

New 19th-century buildings included the brick-built Wesleyan chapel of 1826 (now a shop), (fn. 97) and some older buildings were remodelled or extended for better-off inhabitants, amongst them High House (with its stuccoed front, bay windows, and portico) for one of the Eyre family (fn. 98) New labourers' housing included Forge Cottages, erected next to a surviving brick- and stone-built forge with a cheap, rendered timber frame whose joists were subsequently reinforced with castiron railway lines. (fn. 99) By contrast, late 19th-century infill included some imposing 2½-storey estate cottages built on the main street around the 1880s, combining brick with decorative use of stone, and featuring gothic porches and elaborate chimneys. (fn. 100) Piecemeal additions of varying quality continued throughout the 20th century, houses on the new developments being generally of standard design. (fn. 101) A functional brick-built village hall was erected in 1981, and acquired an external mosaic (by a local artist) in 2000, depicting village scenes. (fn. 102) Outside the village, a large mockTudor mansion designed by Walter Cave was built at Ewelme Downs in 1905, commanding spectacular views, (fn. 103) while Whitehouse Farm ('new erected' in 1803) was remodelled in 1891, and extended northwards (as a private house) in 1990. (fn. 104)

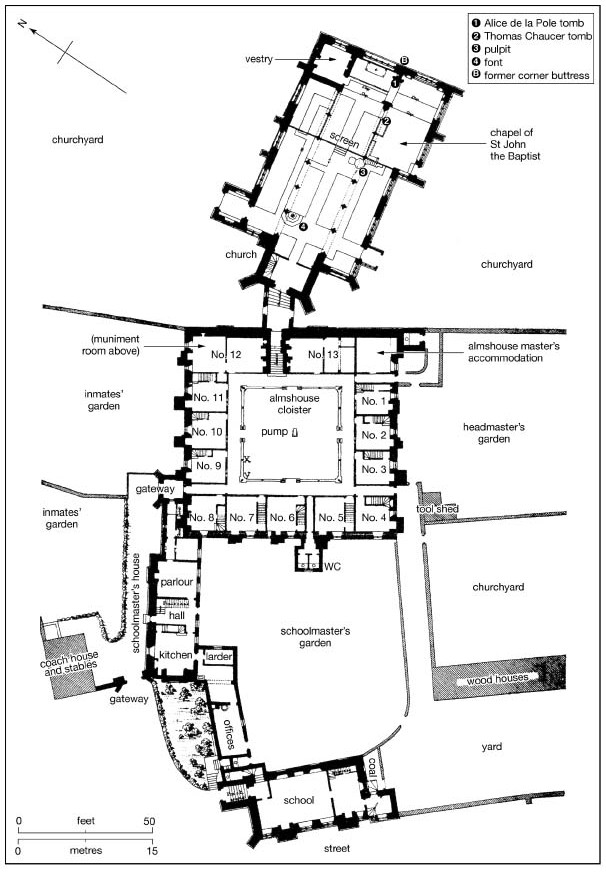

Almshouses and Grammar School (fn. 105)

The almshouses and associated school were built by William and Alice de la Pole in stages between 1437 and the mid 1450s, alongside construction of a lavish new manor house and substantial remodelling of the church. (fn. 106) The earliest phase (probably completed by c.1442) was the almshouse cloister immediately south-west of the church, followed by an abutting grammar masters house running down the slope to a battlemented gateway and, at the bottom of the slope, the school. Like the manor house the buildings incorporate some of the earliest brickwork in the county, its use becoming more extensive in the later phases. (fn. 107)

Ewelme church, almshouses and school in 1858, adapted from a contemporary plan by F.T. Dollman.

As first built the almshouse cloister (Fig. 59) included accommodation for 13 almsmen, ranged around a courtyard and accessed from a covered walkway with a pentice roof. (fn. 108) Eleven of the units comprised a single upstairs and downstairs room linked probably by a recessed stair or ladder, with a stone window (possibly glazed) in the external wall, a timber-mullioned window to the cloister, and a fireplace possibly on each floor. Two units in the north-east range comprised adjoining ground-floor rooms. Between them a stairway leads up to the church through a covered passage, flanked on the left by a first-floor common hall, and on the right by what appears to have always been the almshouse masters accommodation. (fn. 109) The hall retains its original roof and a fireplace against the north wall; its westernmost bay was partitioned as a strong-room, probably by 1459–60 when alterations were made to the 'inner chamber'. (fn. 110) The masters accommodation was probably also heated and possibly included a ground-floor kitchen, but later alterations have obscured its layout. The cloisters external walling is mostly rubble (formerly rendered), with brick used sparingly and for effect, while roofs were tiled from the outset. The central well is original, and was replaced with a pump by the 1820s. (fn. 111)

The south-west porch (Plate 13), with its Flemish-inspired decorative brickwork, is an addition associated with the adjoining domestic range, which was probably allocated to the grammar master from its construction and may have also included rooms for guests and entertainment. The 15th-century part comprises a three-bay timber-framed house encased in contemporary brick, with a narrower annexe of similar construction linking it to the cloister through surviving 15th-century doorways. Blocked windows are visible in the north-west wall, and a massive chimney stack in the south-west gable wall is original. The roof was originally open to the apex, and some timbers at first-floor level retain traces of early 16th-century painted decoration. (fn. 112) A two-storeyed block at the south-east corner was added in 1773–4, (fn. 113) when the older part was remodelled and probably refenestrated.

The two-storeyed brick-built school (Plate 12) (fn. 114) appears to have originally been freestanding, and though functioning by c.1454 may have been the last part to be completed. Stone-mullioned windows with distinctive pointed-arched lights and cinquefoil heads light each floor, and the south front (to the street) features two massive chimney stacks, one with diaper patterning. Heraldic shields displaying the de la Pole, Chaucer, and Burghersh arms are modern replacements of 15th-century originals. Entry is through a heavily altered two-storey porch in the west gable, to the north of which are remains of a medieval spiral stair; the upper floor remains open to its fine timber roof, which has double rows of purlins with windbraces, and moulded arch-braced collar trusses. Both floors were heated, one (perhaps the upper) probably originally providing dormitory accommodation, and the other the main teaching space. (fn. 115)

Periodic repairs to all the buildings were noted from the 16th century, including unspecified (but probably largely cosmetic) alterations to the cloisters and walkway, renewed fenestration, and reordering of the cottage interiors and almshouse masters accommodation, while a clock was mentioned c.1567–1723. (fn. 116) Nonetheless the fundamental layout remained unaltered until a major remodelling in 1970, which reduced the original 13 units to eight. (fn. 117) The school (largely derelict in the early 19th century) was reordered as a National schoolroom c.1830 and subsequently as a primary school, necessitating new stairs and other internal alterations. (fn. 118) The former schoolmasters house (linked to it by a low service range by the 1820s) (fn. 119) became part of the school in 2010, and new classrooms were added on the east in 1999. (fn. 120)

MANORS AND ESTATES

Ewelme belonged in the late Anglo-Saxon period to the Benson royal estate, (fn. 121) from which four separate Ewelme manors were carved before 1086. Their high Domesday assessment (20¾ hides) suggests that some parts lay outside the parish, (fn. 122) and in the 13th century they included woodland near Bix, premises at Roke, and land at Cookley in Swyncombe. (fn. 123) Before the early 14th century the manors were combined into two large estates held by the resident Burghersh and Wace families, and from the early 15th those were merged by the Chaucers and their successors the de la Poles, dukes of Suffolk, who built a lavish new manor house.

After the family's fall the manor forfeited to the Crown, which in 1540 made it the centre of an honor combining the estates of the duchy of Cornwall with the ancient honor of Wallingford. (fn. 124) Ewelme manor itself was sold piecemeal in 1627–8, the Crown retaining only the lordship, the manor house, and what became Warren farm in Nuffield; much of the remaining land became focused on Wace Court or Westcourt (one of the earlier manor houses), and passed in the 18th century to the mostly non-resident Cope family. In 1840 they owned 1,183 a. (just over half the parish), let mostly to tenant farmers. The rest was divided among three sizeable Ewelme freehold farms, some large Benson farms, and more than 40 smaller holdings. (fn. 125) The Crown sold its remaining property in 1817, and the Westcourt estate (following some further enlargement) was largely broken up in the late 19th century.

MANORS TO 1434

The Despenser-Burghersh manor

In 1086 an estate of 4¾ (later 5) hides was held by the king's servant Robert son of Ralph. (fn. 126) The Despensers of Great Rollright acquired it in or before the 12th century, holding it with land in Gloucestershire by serjeanty of acting as the king's despenser or steward: probably the lordship passed to Simon (fl. 1120–30), Thurstan (fl. 1153–77), and Aumary Despenser (fl. 1180–1204), and in 1217 (after various custodies) to Aumary's son Thurstan (d. 1249), (fn. 127) followed by his widow Lucy. (fn. 128) By then the family's Ewelme holdings included an additional ½ knight's fee held of the earl of Oxford and 1/10 fee held of the honor of Nottingham Peverel, making them Ewelme's largest landholders. (fn. 129) In 1265 Thurstan's son Adam (d. 1295) forfeited his lands for involvement in the Barons' revolt, and in 1267 paid £500 for their recovery. By the 1290s he was in financial difficulties, and in 1294 he sold the manor to the royal clerk John Bacon. (fn. 130)

In 1297 Bacon enfeoffed his brother Sir Edmund (then overseas on royal service) for £20 annual rent. (fn. 131) Edmund was granted free warren in his demesne lands of Ewelme in 1310, and the following year settled the manor on himself and his wife Joan; (fn. 132) their daughter and heir Margery predeceased them, and on Edmund's death in 1336 his son-in-law William de Kerdeston (d. 1361) obtained custody during the minority of his and Margery's daughter Maud. (fn. 133) She and her husband John de Burghersh were in possession by 1343 when their son John was born at Ewelme, but both died in 1349 presumably from plague. Wardship and manorial revenues were granted to relatives until 1366, when the younger John secured possession. (fn. 134) He died in 1391 leaving two underage daughters, of whom Maud (d. 1437) married Thomas Chaucer (d. 1434), eldest son of the poet Geoffrey, and himself a prominent politician and administrator. (fn. 135) Maud's sister Margaret and her husband John Arundel (d. 1423) gave up their half-share in 1417 in return for £8 13s. 4d. annual rent. (fn. 136) Chaucer expanded his estate by buying the other Ewelme manor (below) and the neighbouring manor of Swyncombe, where he created a park, and at his death he held over 1,000 a. of demesne in the two places. By then the former Despenser manor was held as ¼ knights fee rather than by serjeanty. (fn. 137)

The Wace manor

A separate 5½-hide estate was held in 1086 by the Norman tenant-in-chief Walter Giffard, and of him (with other Oxfordshire manors) by Hugh de Bolbec. (fn. 138) Half of the Giffard estates passed in the 1190s to the earls of Pembroke, who remained overlords in the 1240s. The Bolbec tenancy passed with the barony of Whitchurch (Bucks.) to the de Veres, earls of Oxford, whose overlordship continued in 1372. (fn. 139)

William Wace occupied the manor as a knights fee by the 1220s-40s, (fn. 140) and he or a namesake was lord in 1279. Besides its detached woodland the manor then included a holding at Cookley Green in Swyncombe, occupied by a free tenant as ⅓ knights fee. (fn. 141) Gilbert Wace was mentioned in 1309–10 (fn. 142) and another William in the 1320s–50s, (fn. 143) his son Sir Gilbert succeeding before 1360. That Gilbert served in various official capacities, and also rented the Despenser manor for 20 marks a year. In 1397, when old and infirm, he conveyed most of his lands to Thomas Chaucer for a £20 life annuity, and following his death c.1409 the Wace manor remained part of Chaucer's Ewelme possessions. (fn. 144)

A separate ½ knight's fee, held of the earldom of Oxford by the Despensers in the 13th century, derived presumably from the same Domesday estate. It seems to have subsequently become part of the Burghersh and (later) Chaucer manors, along with 3 yardlands belonging to the earldom. (fn. 145)

Other manors

Of the two other Domesday estates, one (rated at 8 hides) was held before the Conquest by Ulf, and after it by the Fleming Gilbert of Ghent (de Gand) and his tenant Robert of Armentères. (fn. 146) Appurtenances included a house in Wallingford. (fn. 147) The overlordship remained with the Ghent barony of Folkingham (Lincs.), which was divided among coheiresses in 1298. The Armentères' interest descended through the male line until the 1270s, when it passed through marriage to the de Lisles of Kingston Lisle (Berks.). Their interest was still recorded in the 1360s. (fn. 148)

By the 13th century the 8 hides had been divided into smaller estates held of the overlords by undertenants. Organus Pipard held a knight's fee of the Ghents in 1235–6, which passed by 1242–3 to Henry son of Robert, and by 1279 to Henry's unnamed heirs. By then it was reckoned at ½ knight's fee and contained 3 hides made up mostly of free tenures, of which some (held by Walter of Huntercombe and Bec abbey) lay possibly in Nuffield or Swyncombe. A separate Ghent estate, reckoned in 123 5–6 at ¼ knight's fee, was held by the de Sandford family, and in 1279 (when held of the earl of Oxford) comprised 4 yardlands held by 11 free tenants. Other Ghent/ Armentères lands were held by Henry son of Judocus (¼ knight's fee in 1235–6) and Robert de Haltested' or Halensted' (⅓ fee in 1242–3), while William Wace held some small parcels in 1279. (fn. 149) All those estates were apparently absorbed into the two main 14th-century manors. (fn. 150)

The fourth Domesday estate, assessed at 2½ hides, was held in 1086 by Ranulf Peverel (d. c.1091), a major tenant-in-chief in East Anglia. Ranulf's son William died before 1129/30, when most of the family's estates were back in Crown ownership. (fn. 151) The manor was not mentioned later, and was probably absorbed into the Despenser-Burghersh holdings. (fn. 152)

A separate ½ knight's fee held by the Montsorel family in the 13th century was apparently derived from a 2-hide estate held by Theoderic the goldsmith in 1086, when it was recorded under Benson. The fee was held of Hampstead Norris manor (Berks.), where Theoderic also had property. (fn. 153) The overlordship passed with Hampstead to the Cauz and Sifrewast families, of whom John de Montsorel held the estate in 1242. (fn. 154) William de Montsorel still held it for scutage in 1285, (fn. 155) but it too seems to have become absorbed into the other manors.

EWELME MANOR FROM 1434

After Thomas Chaucer's death the combined Ewelme and Swyncombe estate passed first to his widow Maud and in 1437 to their daughter Alice, the wife of William de la Pole, earl (and later duke) of Suffolk. (fn. 156) In 1440 the de la Poles added adjoining land in Nuffield, south of Ewelme Downs, (fn. 157) where they probably created a warren. (fn. 158) Their Ewelme building projects were interrupted by Williams exile and assassination in 1450, but Alice successfully preserved the ducal estates, largely by abandoning the family's long-standing Lancastrian loyalties in favour of new Yorkist alliances. In 1475 she was succeeded by her son John (d. 1492), 2nd duke of Suffolk and brother-in-law to both Edward IV and Richard III. (fn. 159) He was succeeded by his younger son Edmund, who was demoted to the rank of earl by Henry VII and fled abroad in 1501, prompting seizure of his estates. Formally attainted in 1504, he was imprisoned from 1506 and executed in 1513. (fn. 160)

Ewelme was one of several manors vested in trustees for the life of Edmund's widow, (fn. 161) but the Crown nevertheless administered the manor directly. (fn. 162) In 1525 Henry VIII granted it to Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk, with appendages in neighbouring parishes, but in 1535 demanded its return in exchange for lands elsewhere. (fn. 163) Subsequently it formed part of the settlement on Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I) in 1550, (fn. 164) and on Charles, Prince of Wales (later Charles I) in 1619. (fn. 165) In 1627–8 the Crown sold it piecemeal, (fn. 166) retaining various fee farm rents which were also later sold; (fn. 167) otherwise it kept only the manor house site (11½ a.) with its much-reduced buildings, the warren (137 a.) in Nuffield parish, and manorial rights, including certainty payments and a few small quitrents. (fn. 168) All those premises and rents were leased, for much of the 18th century to the non-resident Hucks family, (fn. 169) and in 1817 they were sold with remaining Crown property in Wallingford and vestigial rights associated with the honor of Ewelme. (fn. 170) The lordship of Ewelme was bought separately from the house and land, first by Jacob Bosanquet and in 1821 by the earl of Macclesfield, whose successor was still deemed lord in 1939. (fn. 171)

THE WESTCOURT (WACE COURT) ESTATE

Following the break-up of Ewelme manor a large estate became centred on Wace Court or Westcourt, the former manor house of the Wace family. (fn. 172) By the early 16th century Wace Court farm was a major leasehold of c.368 a., made up chiefly of former demesne and let on long leases to gentry or their subtenants. (fn. 173) In 1628 it was sold to the tenant Bartholomew Hone for £400, reserving £25 17s. 4d. rent to the Crown; (fn. 174) the rent was later sold, and remained payable in the 19th century. (fn. 175) Hone mortgaged the estate, and after his death in 1650 his widow and sons sold it to Francis Martyn of Over Winchendon (Bucks.), who moved to Ewelme and added other properties. By his death in 1682 the estate covered c.1,265 a., half of it inclosed, and was held with several fee farm rents from other estates. Under Martyn's will the estate was briefly divided amongst relatives, but from 1683 it was reunited by Thomas Tipping of Wheatfield, who settled at Westcourt and served as MP for Oxfordshire and later for Wallingford. In 1687 he sold the estate to his brother William, who enlarged it further and died in 1729. His successor was his granddaughter Penelope, the only child of his daughter Penelope and her husband the Hon. Harry Mordaunt. (fn. 176)

Penelope (d. 1737) married Monoux Cope (d. 1763), eldest son of John Cope, Bt, of Bramshill (Hants). From them the estate descended with the baronetcy, passing to John Mordaunt Cope (d. 1779), his cousin Richard (d. 1806), Richard's nephew Denzil (d. 1812), and Denzil's brother John (d. 1851). (fn. 177) Under family trusts Denzil's widow Dorothea received a £500 annuity, and by her will left the reversion after Johns death to her nephew Francis William Lock Ross (d. c.1861). He left it to his wife Anna Maria (d. 1865) with remainder to his cousin Henry William Francis Greatwood, who in 1875 sold it for £39,000 to Thomas Taylor of Aston Rowant. After the 1730s–40s none of the owners lived in Ewelme, and the estate (1,180 a. in 1875) was mostly let to tenant farmers. (fn. 178) Taylor (d. 1892), a Lancashire mill owner, built up extensive estates in the south-west Chilterns, (fn. 179) and in Ewelme added Eyres farm (c. 200 a.) and Cottesmore farm (157 a.) and some cottages and gardens, along with Ewelme Park farm in Swyncombe. (fn. 180) From 1881 his property was increasingly mortgaged, (fn. 181) and c.1890–2 the Ewelme estate was sold off in parcels, chiefly to tenants. (fn. 182)

MANOR HOUSES AND RESIDENCE

Ewelme's Domesday lords held extensive estates elsewhere, but as all four manors had land in demesne they probably included manor houses. The Waces resided from the 12th or early 13th century to the early 15th, (fn. 183) and the Despensers and their successors to the mid 14th, (fn. 184) followed, from the 1390s, by the Chaucers and de la Poles. (fn. 185) The latter built a lavish new house which, during the 16th century, became an occasional royal residence. (fn. 186)

The Waces' house occupied a site adjoining Parsons Lane on the villages north-western edge. (fn. 187) The location of the Despenser–Burghersh manor house is unknown, but may have been partway down the hillside below the church, where excavation uncovered a substantial flint and mortar wall with late 13th- or early 14th-century finds; (fn. 188) if so the buildings had gone by the 1430s-50s when they were replaced by the almshouses and school, (fn. 189) leaving a large demesne barn nearby. (fn. 190) An alternative site is that of the de la Poles' large moated complex in the village's lower part, (fn. 191) though whether that overlies earlier manorial buildings is unknown.

With the manors' gradual unification most of the earlier sites presumably became redundant. The Waces' house survived as a farm- and (later) gentry house, but from the mid 15th century Ewelme's only manor house was that built by the de la Poles. Most of the buildings there were demolished in the early 17th century, leaving a fragment which was remodelled as a private house in the 1830s.

Ewelme Manor House ('Ewelme Palace') (fn. 192)

The House to 1612 The de la Poles' new manor house was a lavish aristocratic complex, (fn. 193) influenced in part by Henry VI's buildings at Eton College (with which William de la Pole was involved), and making extensive use of brick, which was still virtually unknown in Oxfordshire. (fn. 194) Building probably began in the mid 1440s after William became a marquis, (fn. 195) and the family was regularly resident thereafter. (fn. 196)

The 15th-century buildings (fn. 197) were grouped around two adjoining courtyards south of the village street, the main domestic ranges within a moat, and ancillary buildings around a base court to the east. Entry was through a two-storeyed gatehouse probably on the base court's east side. The main house seems to have been quadrangular, with a regular and probably symmetrical groundplan incorporating a great hall, parlour, chapel, and (apparently) separate suites of rooms for male and female members of the household. (fn. 198) Like Eton's Cloister Court it was brick-built with stone windows, doorways, and buttresses, and was richly furnished with tapestries and painted or moulded family devices, (fn. 199) while the hall was spanned by unusual wrought- or cast-iron beams. (fn. 200) A keeper of the garden mentioned in the 1530s suggests landscaping, (fn. 201) and in 1649 an orchard west of the moat contained ten regularly arranged fishponds which survived in 1817. (fn. 202) A 'fair park' mentioned by Leland was probably Ewelme park up on the downs. (fn. 203)

Ewelme manor house in 1729: the former base-court lodging range from the north-east, with remains of the main house's moat to the right. (For site see Fig. 52.)

Following the Crowns seizure of the de la Pole estates the house became an occasional royal residence. Henry VIII stayed there in 1518 and on several later occasions, (fn. 204) its convenient location being presumably one of the reasons he recovered the manor from Charles Brandon. Brandon himself lived there regularly from 1525–35, and claimed (besides enlarging Ewelme park) to have spent £1,000 on the house, although the king insisted that the buildings still needed expensive repair. (fn. 205) Elizabeth I visited in 1568 and 1570, but by then the buildings were increasingly run down, and by 1609 they were 'ruinous and totally decayed'. (fn. 206) Most were demolished soon after 1612 when a detailed survey was made of the buildings and fittings, leaving the gatehouse (removed before 1649), and a single brick lodging range which formerly closed the base courts south side, preserved only because sale of materials was thought unlikely to cover the cost of demolition. (fn. 207)

The Site from 1612 Though in Crown ownership until 1817, from the 17th century the site was leased to non-resident gentry with the warren and, by the 18th century, with the remains of Wallingford Castle. (fn. 208) The Ewelme premises were sublet to local tenants, who exploited the grounds and fishponds and used the former lodging range for menial purposes: in 1649 part was a pigeon house, and before 1715 part was used as a laundry. (fn. 209) The ranges higher-status western part was used for manor and honor courts by the early 17th century and, under the terms of Crown leases, into the 18th, (fn. 210) one reason, perhaps, for its survival. In 1786 the range was adapted to accommodate parish paupers. (fn. 211)

In the 17th century the lodging range still contained five rooms on each floor, adjoining the 'house' or room where the manor courts were held. Access was originally by an external wooden gallery, which survived in 1612. (fn. 212) A drawing of 1729 (Fig. 54) shows a long two-storeyed block with upper and lower rows of doors and windows, each serving a two-bay room heated by chimney stacks in the rear wall; a small roof-opening near the east end perhaps reflected the range's brief use as a pigeon house. A grander door and window at the west end marked the three-bayed upper hall in which the courts were presumably kept. (fn. 213) By 1821 much of the range had lost its upper storey, leaving only the two westernmost lodging rooms (one on each floor) and the upper hall. Those retained their medieval north doorways and some medieval window-openings, together with a puzzling post-medieval chimney stack on the western gable above three tiers of windows. (fn. 214)

The site was bought in 1817 by Edward Rudge (d. 1835), (fn. 215) whose son Edward remodelled the ranges west end as a small gentry house which he occupied with his family and servants. (fn. 216) The interior was completely reordered, creating a central entrance hall with a projecting brick porch. Service ranges at the rear were added or remodelled, a new staircase was inserted, and sash windows replaced the surviving medieval openings, of which some remain visible in outline. The rest of the range was removed around the same time, and the moat and fishponds filled in. (fn. 217) The houses three westernmost bays retain the high-quality 15th-century arch-braced roof of the former courthouse, incorporating a double row of purlins supported by sharply curved wind braces, while the houses eastern part (over the former westernmost lodging chamber) retains a 15th-century roof of different character. (fn. 218) In 1868 the premises were acquired by the Ewelme Almshouse Trust, (fn. 219) which leased it to resident tenants and remained the owner in 2015. An extensive restoration was carried out in 1975–6 under the supervision of Messrs King and Chasemore. (fn. 220)

Wace Court (Westcourt)

Wace Court (so called by the 1430s) (fn. 221) was the Wace family's principal residence probably by the 13th century. In 1434 both it and the Burghersh site were reportedly worth nothing, (fn. 222) but the Chaucers must have occupied one of them, and Wace Court continued as a leasehold farmhouse following the building of the de la Poles' new complex in the 1440s. Lessees included Thomas Spyer (fl. 1515), in 1522 the courtier Henry Norris (who served as bailiff, woodward, and keeper of the park), in 1535 the duke of Suffolk's steward Thomas Carter, and from 1571 members of the Mercer family, (fn. 223) who evidently lived there. (fn. 224) In 1609 the buildings included a six-bay dwelling house, five- and six-bay barns, a stable, and a dovecot, brewhouse, and gatehouse. (fn. 225)

Wace Court (Westcourt) from the south-west in 1764. The farmyards lay off to the left.

The Hones lived there by the 1620s, (fn. 226) followed from c.1650 by Francis Martyn, who largely rebuilt it. In 1662 it was taxed on 19 hearths, and at his death was described as a 'new brick house' with a 'well-planted' walled garden, three great barns, six stables, a pigeon house, and two yards surrounded by farm buildings. (fn. 227) Mid 18th-century drawings show a south-facing H-shaped house of two storeys and attics, opening to a forecourt garden. The central hall was flanked by projecting parlours and dressing rooms, with services around a rear courtyard and barns and cottages in two large yards to the west. (fn. 228) The Tippings lived there until 1729, followed by Monoux and Penelope Cope, (fn. 229) but by the 1750s the farm buildings were let to local farmers and the house to Hildebrand Jacob (d. 1790), Bt, (fn. 230) who laid out an avenue of limes to the east. (fn. 231) After his death the site was leased to farmers and as school accommodation, (fn. 232) and though the house was reportedly still standing in the 1850s, by the 1870s it had been demolished, leaving adjacent agricultural buildings and a cottage called The Mount. (fn. 233) In the 1960s a new housing estate (Chaucer Court) was built on the site, and The Mount was demolished, surviving barns being converted for domestic use. (fn. 234)

OTHER ESTATES

Ewelme's manors included numerous free tenancies by the 13th century, although few exceeded a yardland or are traceable as stable holdings. (fn. 235) By the 15th century several large leaseholds were also emerging, (fn. 236) of which some became sizeable freeholds following the manors break-up in 1627–8.

'Cottesmoreslondes' (mentioned from 1476) belonged presumably to the medieval Cottesmore family, recorded as prominent landholders from the 14th century to the 16th. (fn. 237) By the 1510s 'Cottesmore farm' was let on long leases for £6 (later £6 10s.) a year, and in 1609 totalled 270 a.; 16th-century tenants included members of the locally important Simms, Spindler, Slythurst, and Marmion families. (fn. 238) In 1627 it was sold to the tenant Andrew Field, reserving the fee farm rent to the Crown, (fn. 239) and in 1673 it was among Ewelme premises sold by Gilbert Crouch, gentleman, to the judge Sir Matthew Hale, (fn. 240) whose son Edward (d. 1682) and his descendants lived there until the 1740s. (fn. 241) The estate passed later to the farmer William Read (d. 1767) and his descendants the Greenwoods and Heaths, between whom it was divided in the 1770s-80s. (fn. 242) In the later 19th century it was absorbed into Thomas Taylor's Ewelme estate as a 157-a. farm. (fn. 243)

A comparable holding was accumulated by the medieval Beke family, who were recorded in the 14th and early 15th century (fn. 244) and lived presumably at Bekes' Place on the Fifield road. (fn. 245) By the 1510s the 'tenement and lands called Bekesplace' were let for £4 2s. to the Haywards and (later) Hatchmans, and in 1627 they were sold to George Carleton, gent, passing by the 1650s (with over 100 a.) to Mary Dunch of Newington. (fn. 246) In 1699 the freehold was bought by Charles Eyre of Goulds Farm, one of a prominent family of Benson and Ewelme yeomen who were already lessees. Thereafter it became part of the emerging Eyres farm, an accumulation of freeholds which exceeded 200 a. by 1840 and 300 a. in 1874, when it was bought by Thomas Taylor. (fn. 247) The Eyres' main farmstead was at the bottom of Eyres Lane, and Bekes' Place (latterly called the Tavern House from its proximity to the Lamb Inn) was demolished in 1876. (fn. 248) The holding still owed a fee farm rent of £8 4s. (then payable to Francis Martyn) in 1682. (fn. 249)

The third major freehold in 1840 was Fords or Days farm (then 161 a.), focused on a large 17th- or 18th-century farmhouse in the village's lower part. (fn. 250) Presumably it derived from a leasehold called Fords Place by 1515, (fn. 251) or from an apparently different leasehold occupied by Thomas Ford for 305. rent in 1609 and sold in 1627. (fn. 252) The holding subsequently passed from Francis Martyn (d. 1682) of Westcourt to his nephew Edward, (fn. 253) and to the prosperous Ewelme yeomen John (d. 1701) and Robert Day (d. 1728), (fn. 254) followed before 1745 by the Bruchs of Wallingford. (fn. 255) They leased it until 1784 when it was sold to the Ewelme farmer John Lane (d. 1790), followed by his relatives the Franklins and, from 1904, by the Edwardses, (fn. 256) who remained there in 2013.

A holding focused on the outlying Whitehouse Farm was separated from the Westcourt estate in 1631, passing to the Blackalls and, in 1803, becoming part of the Lowndes Stones' Brightwell estate. Known formerly as Cadwell's, it may have derived from lands held of the Despensers by Roger of Cadwell in 1279, and by 1681 included a house surrounded by 20 a. of inclosures. (fn. 257) The name Whitehouse was established by 1767. (fn. 258) A few acres owned by Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1840 belonged to its Berrick Salome and Benson estates, while a 107-a. estate at Westwood farm, acquired in the 18th century by the Freemans of Fawley Court (Bucks.), lay in Ewelme's detached part adjoining Bix and Nettlebed. (fn. 259)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIGS 4 AND 50)

The parish's varied landscape extends from the vale to the Chiltern foothills, suggesting a planned allocation of resources when Ewelme's late Anglo-Saxon estates were created. (fn. 260) Open-field arable dominated the western part until 1863, the parish's strips either scattered amongst the large shared fields of Benson, Ewelme, and Berrick Salome, or lying more closely grouped within the 'home parish'. (fn. 261) A surviving common occupies a shallow valley south-east of the village, beyond which rise Ewelme Downs and Huntinglands, both inclosed for pasture by the 15th century. Limited meadow was available near the village stream and in detached areas by the Thames and river Thame, (fn. 262) while fishponds were mentioned in the Middle Ages, (fn. 263) and private fishing rights in the stream in the 19th century. (fn. 264) Detached woods lay near Bix and in neighbouring Swyncombe, which was held with Ewelme in the later Middle Ages.

In 1840 the parish was 85 per cent arable, with around 1,000 a. (almost half the cultivated area) still lying in open fields. (fn. 265) The proportion of pasture was probably greater in the late Middle Ages, with downland closes used for grazing. Even so, extensive arable most likely characterized Ewelme for much of its history.

Open Fields, Pastures, and Meadow

Ewelme may have had its own core fields (distinct from Benson's) by the 13th century, when land near the mill lay in 'Ewelme fields'. (fn. 266) By the 17th or 18th century there were at least eight 'home fields' of varying size, including Home and Merrycroft (later America) fields north-west of the village, Grove, Middle, and Gravel Pit (earlier Church or Warren) fields to its north and north-east, and Clay, Rabbits Hill, and Monday (or Munday) fields to its south. Warren Bottom field lay east of Warren Bottom road. (fn. 267) In 1771 the home fields were reckoned at 1,260 a. and formed three groups, each following a separate four-course rotation. The westernmost group included Scaldhill field (shared with Benson and Berrick Salome), but otherwise the fields formed an independent unit. (fn. 268) Nevertheless many Ewelme holdings included additional strips in the shared fields. (fn. 269)

By the mid 18th century the home fields included some sizeable blocks of consolidated land, which may have included medieval demesne. (fn. 270) Smaller strips of ½ a.–2 a. survived into the 19th century, but consolidation continued during the 1840s-60s, facilitated by the fact that much of Ewelme remained in single ownership. By the 1880s the fields (though never formally inclosed) (fn. 271) had been thrown into a few large private closes, and in 1891 the changed landscape was recognized in a new tithe apportionment. (fn. 272)

Common grazing was permitted after harvest in both the shared (or 'intercommoning') and home fields, (fn. 273) while some private closes were commonable from Lammas (1 August). (fn. 274) Permanent pasture included the 53-a. cow common by the village, (fn. 275) which by the 17th century belonged to the Westcourt estate, and was open for parishioners' cattle from March or May to 29 September. The rest of the year it was grazed by sheep, but appears (as later) to have been reserved for the owner of Westcourt or his lessee. (fn. 276) A similar arrangement continued in the 1880s, when 13 farmers retained a total of 58 cow commons there from 12 May to 11 October. (fn. 277) Additional commoning was allowed in the warren at Grendon (in Nuffield parish), which belonged to Ewelme manor from the 15th century; in 1721 (when the land became arable) £4 of the rent was awarded to Ewelme's common herdsman in recompense, and by 1817 the lessee was required to provide a bull for Ewelme cow common. (fn. 278) Disputes over commons arose intermittently from the Middle Ages, (fn. 279) and in 1898 attempts to undermine smaller freeholders' rights on the cow common met with strong opposition. (fn. 280)

The largest common meadows lay outside the home parish near the Thames, where those with strips in the shared fields presumably had rights. (fn. 281) Meadow in Ewelme itself was confined chiefly to small demesne parcels, including 28 a. itemized in 1086; (fn. 282) a reported 80 a. of 'hilly meadow' in 1356 was more likely inclosed downland pasture, (fn. 283) although Cottesmore and Westcourt farms each had 11 a. of private meadow in the 17th century. (fn. 284) The meadows' scarcity attracted high prices, with some on the Chaucer manor in 1434 valued at 12d. an acre compared with 2d. for arable and 1d. for pasture. (fn. 285)

Early Indosures, Parks, and Warrens

By the late 18th century the home parish included 800 a. of inclosures chiefly on the eastern downlands, with some others around the village and at Cottesmore. (fn. 286) Most probably dated from the later Middle Ages, when the Wace and Burghersh manors included an estimated 260 a. of inclosed demesne pasture probably also on the downs. (fn. 287) The chief motive was presumably sheep grazing, though the name Huntinglands (for a 100-a. area in the north-east) may indicate an undocumented park; (fn. 288) the nearby Ewelme park (in Swyncombe) was certainly established in the early 15th century, and the name King's Standing (on Ewelme downs) may imply its later encroachment into Ewelme. (fn. 289) An adjacent rabbit warren at Grendon (in Nuffield) was probably created after the de la Poles acquired land there in 1440, (fn. 290) and later warrens at Rabbits Hill and Middle Hill were probably also medieval, the Middle Hill warren covering 55 a. in 1649. (fn. 291) From the 17th century the inclosed downlands (c. 500 a. in all) belonged to the Westcourt estate, and formed the basis of some large leasehold farms. (fn. 292)

Some large closes further west were probably associated with the Waces' medieval manor house, the mill, or the medieval farms at Cottesmore and Bekes' Place. (fn. 293) A few crofts were mentioned from the 13th century, (fn. 294) and in 1609 several copyholders had small pasture closes adjoining their houses. (fn. 295) Otherwise the only sizeable private closes were consolidated holdings in the open fields, estimated at 155 a. in 1771. (fn. 296)

Woodland

Three of Ewelme's manors included woodland in 1086, (fn. 297) although much may (as later) have lain outside the parish. William Wace's 60 a. in 1279 was probably at Westwood (formerly Wace's wood) near Bix, while a Wace tenant at Cookley had 32 a. presumably in Swyncombe. (fn. 298) Another 30 a. on the Despenser and Pipard manors may have been in Swyncombe or at Heydon on the Ewelme-Swyncombe boundary (fn. 299) Much larger amounts of woodland were recorded in the 15th century when Swyncombe and Ewelme manors were held together, but its whereabouts were not specified. (fn. 300)

Adam Despenser's tenants in 1279 included Jordan the forester, (fn. 301) and in the 14th and 15th centuries the woods, though not especially valuable, provided demesne wood-pasture and coppice wood. (fn. 302) In the 16th and early 17th century the Crown appointed high-status keepers to administer the Ewelme manor woods in Swyncombe and beyond, (fn. 303) and by then there were periodic timber sales to the navy or for making buildings, barrels and boards. (fn. 304) Ordinary tenants may have benefited less from the woodland, although in 1535 a lease of Wace Court included the right to take firewood and timber for repairs from Swyncombe wood, (fn. 305) and in 1555 a Ewelme yeoman killed a neighbour with a forest bill. (fn. 306) In the 1570s the woods were generally coppiced on a 7-year cycle, (fn. 307) and in 1623 comprised beech and oak. There were then 'diverse husbandmen desirous to buy [trees] for their necessary uses', the woods lying 'near unto the vale country'. (fn. 308)

The detached woods were separated from Ewelme manor in the early 17th century, (fn. 309) leaving only hedgerow trees and a few small shaws within the parish. Closes adjoining Ewelme manor house in 1649 included 94 elms and 20 'short trees' for fuel, (fn. 310) while Westcourt had a few small orchards and copses. (fn. 311) By the 1770s the only sizeable coppice was a 7½-a. shaw made up of beechwood, (fn. 312) with fuel presumably bought in or taken from hedgerows. (fn. 313) The parish contained little more woodland in the early 21st century, when there were a few small scattered plantations and a slightly larger wooded area around Ewelme Down House. (fn. 314)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

In 1086 all four Ewelme manors had demesne farms worked by up to four families of slaves or servi and stocked with 1 or 2 ploughteams, while tenanted land was divided among 23 villani and 16 lower-status bordars. Over all there were 17½ ploughteams (7 on the demesnes and 10½ shared by tenants), though as the combined manors had land for 24 ploughs they were apparently not all being fully exploited. The small Peverel manor had doubled in value since 1066 (to £4), while the others had retained their values of £5–£6. (fn. 315) An independent pre-Conquest farm may be recalled in the field name 'the Hide' (for an inclosed area north of the village street), (fn. 316) but if so it had apparently been absorbed into one of the manors.

The late 13th-century tenurial pattern was more complex, suggesting intervening fragmentation and subinfeudation, creation of free tenancies, and perhaps some over-simplification in the Domesday description. (fn. 317) Of 51 tenanted yardlands, (fn. 318) 9¼ were held in villeinage by c.15–16 tenants (most of them on the Despenser and Pipard manors), who owed rents and relatively light harvest services. (fn. 319) Individual villein holdings ranged from whole yardlands (apparently c.40 a.) (fn. 320) to ¼ yardlands, and there were a dozen or more cottagers who presumably had only gardens. The other 41 yardlands were held freely for rent and suit of court (and sometimes for hidage and scutage) by c.60 tenants, not all of them resident, whose individual holdings ranged from a few acres to 2 yardlands or more. Some such families featured amongst Ewelme's wealthier taxpayers in the early 14th century, (fn. 321) and benefited from an active local land market. (fn. 322) Large-scale demesne farming continued. Both the Despensers and the Waces had 10 or more yardlands in hand (the former under three different overlords), and woodland too was directly managed. Demesne labour was presumably bought in as required, tenant services on the Wace manor being apparently available from only two villein holdings and a few cottagers. (fn. 323)

Early 14th-century subsidies suggest that Ewelme was among the area's more prosperous and populous parishes, (fn. 324) and in 1336 the large sum of £120 was paid for custody of Edmund Bacons manor, (fn. 325) which may have yielded up to £20 a year. (fn. 326) Mid-century plagues had a long-lasting impact, however. Mortality in 1349–50 reduced the same manors free and customary rents from £4 115. to only 375. (the victims including the lord and his wife), (fn. 327) and thereafter Ewelme's population probably remained below 13th-century levels until the 18th century (fn. 328) In closure of downland in the east of the parish (for grazing and possibly as parkland) probably followed. (fn. 329) Even so rents on the combined Chaucer manors rose to £7 by 1434, (fn. 330) and demesne farming apparently continued, since in 1397 Thomas Chaucer sold nine horses and all his corn in Ewelme to the local freeholder William Beke for 41 marks (£21 6s. 8d.). (fn. 331) At Chaucer's death his combined Ewelme demesnes totalled 260 a. of arable, 260 a. of pasture, and an acre of meadow, supplemented by detached woodland. (fn. 332) By then some of the large, partly inclosed freehold and leasehold farms visible in the 16th and 17th centuries were probably also emerging. Turner's (in Benson) was mentioned from the 14th century, (fn. 333) and a settlement of de la Pole lands in 1476 mentioned various other holdings including Cottesmoreslondes (later Cottesmore farm), Brittoneslondes, Derkeslondes, Croucheslondes, and Turkevileslondes, in Ewelme, Benson, Newnham Murren, and Nuffield. (fn. 334)

The size of the open fields suggests that grain production was paramount, although a late 12th-century grant of demesne tithes mentioned corn, lambs, piglets, cheese, and wool, (fn. 335) and pastoral farming probably expanded in the late 14th and 15th centuries, particularly on the newly inclosed grazing lands. The de la Poles had long-standing connections with the international wool trade, and in 1448 William (d. 1450) became governor of the wool staple at Calais. (fn. 336) Herbage and pig-grazing in Ewelme park (in Swyncombe) was mentioned in the 16th century, (fn. 337) and tenants' common rights recorded in the early 17th century (for sheep as well as cattle) probably had medieval antecedents. (fn. 338) More generally the presence of gentry and aristocracy presumably boosted local demand and employment at least sporadically, particularly during the de la Poles' great building campaigns of the 1430s-50s. (fn. 339)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

In the 16th and early 17th century most inhabitants still occupied small or moderately sized copyhold farms, granted usually for three lives and held for modest rents, varying entry fines, and heriots payable in cash or livestock. In 1609 there were 27 such tenants, (fn. 340) of whom half a dozen had only a cottage with an acre or two. By contrast Richard Eyre and William Poxon had over 60 a. and two others over 30 a., chiefly in the common fields. Much larger were the leaseholds centred on Cottesmore (270 a.) and Westcourt farms (338 a.), the latter run by the resident Mercer family, and made up mostly of inclosed demesne. In 1581 William Mercer was Ewelme's weathiest inhabitant, and Maximilian Mercer (d. 1614) left goods worth the exceptional sum of £859, including a valuation of £600 for the Westcourt lease. (fn. 341) The parish's detached woods were generally kept in hand and administered (with Ewelme park) by high-status royal officials, though in the later 16th century they were sometimes leased. (fn. 342)

The break-up of the royal estate in 1627–8 (fn. 343) probably accelerated accumulation of larger holdings, reflected in the presence of some prosperous farmers. John Eyre (d. 1684) and John Potlock (d. 1698) each left goods worth over £100, while James Warner (d. 1677) and John Day (d. 1701) left over £200, and John Warner (d. 1685), exceptionally, £552, much of it in livestock and agricultural produce. (fn. 344) Westcourt, too, remained the centre of a large commercial farm under Francis Martyn and the Tippings, (fn. 345) though by the mid 18th century much of its land was leased. By the 1780s there were 6 or 7 substantial freehold or leasehold farms including Cottesmore (split between Richard Greenwood and John Heath), Eyres' (owned and run by Charles Eyre), Fords (let to Edward Leaver), and Tidmarsh's. (fn. 346) Fords (172 a.) was let for c.10s. an acre, fairly average for middling-quality open-field arable. (fn. 347) Thomas Heath held two formerly separate farms from the Copes (possibly 650 a.) together with Warren farm in Nuffield, and as later some Benson farms extended into Ewelme. Smallholdings continued, though by then many inhabitants were labourers with only small gardens or closes and limited common rights, (fn. 348) a situation reflected in relatively high poor relief costs. (fn. 349)

Farming remained mixed with an arable bias, though sheep-rearing and dairying were important, and dung (for fertilizer) was sometimes itemized in inventories. (fn. 350) In 1683 the large Westcourt estate supported 100 sheep and a few cows and pigs worth £80 in all, compared with 156 a. of corn worth £280. (fn. 351) James Warner (d. 1677) had nearly 300 sheep, 17 cattle, and 21 pigs, together with 48 a. of wheat, barley, peas, and vetches. (fn. 352) Similar farming on varying scales was common from the 16th century, with many lesser inhabitants owning a few livestock and poultry (fn. 353) Several farmers made cheese or cider (fn. 354) and there was some bee-keeping, (fn. 355) while lesser crops included woad, hops, and hemp, mentioned occasionally along with spinning wheels for linen or wool. (fn. 356) Malt was mentioned from the 1530s, (fn. 357) made sometimes on a commercial scale: Westcourt and several other farms had malthouses in the 17th century, (fn. 358) and in 1695 the maltster John Lane left 33 qrs worth £33. (fn. 359) Crop rotations were adjusted by common agreement in the 1780s, when it was decided to plant the 420-a. fallow with clover or other artificial grasses. The remaining cultivated fields were divided between wheat and barley (210 a. each) and beans or similar (420 a.). (fn. 360) The Eyres and Heaths were by then employing shepherds, of whom some were housed on the Downs. (fn. 361)

Markets (besides Benson) may have included Wallingford, Watlington, Henley, Oxford, and Abingdon, in all of which a Ewelme tanner was owed debts in 1556. (fn. 362) Through Henley, some malt and other produce was probably destined for London, where a few Ewelme inhabitants had family connections. (fn. 363) Individual fortunes nevertheless fluctuated. Civil War disruption seriously affected the miller and presumably local farmers, (fn. 364) while in 1755 at least 20 inhabitants suffered losses totalling £487 following a major fire. (fn. 365) A flash flood in 1749 caused damage at Fords Farm, (fn. 366) while another farmer lost £150-worth of uninsured corn and equipment in 1766. (fn. 367) Farming standards also varied, with Fords reportedly 'ill cultivated' by its lessee Edward Leaver in the 1770s-80s. (fn. 368)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

The Greenwoods, Eyres, and Heaths continued into the 19th century, but increasingly Ewelme farming was dominated by the Franklin family. John Franklin (d. 1824) took over Fords on his uncle John Lane's death in 1790, and by 1840 his sons John, William, and Joseph farmed 1,580 a. (two thirds of the parish) as freeholders and lessees, based respectively at Fords, Lower Farm on Parson's Lane, and New (later White) House on Cat Lane. In 1851 they employed 84 labourers between them. (fn. 369) The family's dominance continued until the 1880–90s, when Fords was leased to a tenant and the incomer Herbert Orpwood (d. 1935) took over Lower and several other farms. (fn. 370) Other prominent 19th-century farmers included the Wallingford-born Thomas Bishop Greenwood (farming c.300 a. latterly from Mill House), while Eyres farm (200–250 a.) was run successively by the Heaths and Deverells, Septimus Garlick, and William Bryant, and the smaller Cottesmore farm by Greenwood and (by 1871) William Atkinson. Some leading Benson farmers (notably the Newtons) also farmed land in the parish. (fn. 371)

Ewelme watercress beds c.1895, looking south-east. Brook Cottage (Smockacre) is visible just left of the stream.

In 1830 the Franklins and John Eyre joined those opposing Thomas Newtons attempts to force inclosure of the shared open fields. (fn. 372) Consolidation of Ewelme's home fields continued piecemeal, however, (fn. 373) and when the shared fields were inclosed in 1863 John Franklin received 104 a. for his freehold land there, and a trustee under Eyre's will 82 acres. (fn. 374) Despite those changes arable-based sheep-corn husbandry continued. Cash crops (principally barley and wheat) still accounted for half the agricultural land in 1889, with another 300 a. producing fodder crops including turnips and swedes, and 177 a. of permanent grass supplemented by 268 a. planted with clover or sainfoin. Livestock included over 1,300 sheep and lambs, 145 pigs, 60 cattle (26 of them in milk), and 44 horses. (fn. 375) Some individual farms were predominantly arable, (fn. 376) though Robert Franklin, with 100 a. of pasture on the Downs, was a substantial mixed farmer. Even so by 1883 he was suffering from the agricultural depression, causing his stock to be distrained to meet rent arrears exceeding £2,000. Still farming in 1891, he moved later into non-agricultural activities. (fn. 377) New initiatives included development of a watercress business by the Smiths of Lewknor and South Weston, who were established at Brownings by 1881, and created cress beds along the roadside stream probably in stages. (fn. 378) The business continued until 1988, with cress initially transported from Watlington station for sale in the Midlands, Covent Garden, and Oxford. (fn. 379) Commercial nurseries north of the main street were established by Stewart Paget before 1899, growing cucumbers and tomatoes under glass. (fn. 380)

The Orpwoods remained Ewelme's largest farmers in the early 1940s, running 862 a. between them from Lower farm, Levers, and Huntinglands. Cottesmore farm (291 a.) was run by Oliver Medley as tenant, Fords (145 a.) by John Edwards (whose family moved there in 1902), and Down farm (286 a.) as a hobby farm by Alexander Gemmell of Ewelme Down House. The Winfields ran 139 a. with Ewelme dairy, and Brownings and Ewelme Manor had 30 a. between them (mostly pasture). (fn. 381) Some arable was laid to grass in the earlier 20th century, (fn. 382) but the parish's over-all balance remained little altered, with around a third under permanent or artificial grass in 1902, 1930, and 1941. In the latter year the parish supported 213 cattle, 406 sheep (a drop from nearly 2,000 forty years earlier), 93 pigs, and over 1,000 poultry; the chief crops were still barley, wheat, and oats, together with fodder crops and small quantities of potatoes. Four farms had tractors, and only 36 workers were employed, falling to 11 by 1960. (fn. 383)

Forge House and its smithy in the early 20th century, with the smith Edward Godden and his wife outside.

Huntinglands was acquired c.1945 by the Watlington-based Roadnight family, which used it for intensive outdoor pig-rearing. (fn. 384) The Orpwoods sold up in 1957, leaving Fords as the largest village-run farm: there, Bill Edwards (occupying 1,200 a. by 1983) specialized in cereals, pig-rearing, and beef cattle, introducing sheep from the 1960s, and trout-farming (in tanks associated with the watercress beds) in the 1970S-80S. The much-reduced farm continued in the early 21st century, run alongside a bed-and-breakfast business, and with its 18th-century farmyard buildings converted to holiday cottages. (fn. 385) Down farm was c.300 a. in 2013, though by then much of Ewelme was farmed from outside the parish. (fn. 386) Most of the area's small local markets had also closed, although some produce was sold through a recently opened farm shop at Britwell Salome. (fn. 387)

TRADE, CRAFTS, AND RETAILING

Medieval occupational surnames included smith, carpenter, and tailor, (fn. 388) and several inhabitants (including women) brewed ale. (fn. 389) A 'merchant' (John Dyer) with Henley and London connections was mentioned in 1421, (fn. 390) and an inn existed by the 16th century (fn. 391)

From the 17th and 18th centuries blacksmiths, carpenters, wheelwrights, shoemakers, and tailors were regularly recorded, with one or more of each probably operating at any given time. (fn. 392) Forges occupied various locations on the village street, (fn. 393) with another (recorded from 1673) at Cottesmore. (fn. 394) Less usual craftsmen included a tanner (d. 1556), (fn. 395) a laceman (mentioned 1684), (fn. 396) a staymaker (mentioned 1776), (fn. 397) and masons (d. 1608 and 1739), (fn. 398) while gravel pits were mentioned from the early 17th century (fn. 399) Shops became established by the 18th century, presumably selling groceries and serving both Ewelme and neighbouring parishes: in 1786 there were four between the Greyhound Inn and Tidmarsh Farm. Contemporary tradesmen included a carpenter, a wheelwright, two shoemakers, a tailor, a butcher, a baker, two carriers, and a possibly itinerant bricklayer, (fn. 400) while two blacksmiths included one of the Jacob family, recorded as smiths from the 1630s-1790s. (fn. 401)

A similar range of trades continued in 1851, when there were still 3 blacksmiths (one of whom sold beer), 2 shoemakers, 2 bakers-cum-grocers, and a tailor. Thomas Garlick at the Greyhound was both innkeeper and butcher, while the wheelwright John Hathaway (at Thatchings) had expanded into iron-founding and agricultural machine-making. A few women worked as dressmakers, and 25 (plus two men) as domestic servants. (fn. 402) Brakspear's Brewery opened a small distribution depot behind the Shepherds Hut pub before 1901, managed by the former farmer Robert Franklin, (fn. 403) and c.1900 Sidney Heather started a drapers business at London House (near the Greyhound), which included millinery and boot-repair and served surrounding villages. It continued in 1939, along with grocers' and bakers', a sweet shop, a smith and carpenter, an agricultural engineer, and a motor garage. Thereafter traditional crafts declined and, as transport improved, local shops gradually closed, one near the school briefly becoming a pottery (fn. 404) A thatcher continued in the 1980s, (fn. 405) and Ewelme Village Store (run on a non-profit basis) in 2015. (fn. 406)

After the Second World War RAF Benson provided additional employment, partly counterbalancing declining agricultural work. (fn. 407) A honey factory started at Ewelme in 1952 employed 50 local people by the 1970s, having sold its hives and switched to bottling; it closed in 1990, and moved to Wallingford. (fn. 408) Gravel-quarrying south-east of the village was intensified from 1947 by Grundon's, which later exploited the quarries for waste disposal, and in 1999 opened a nearby recycling facility (fn. 409) Ewelme Coachworks (offering commercial vehicle repair) continued behind the former garage in 2013, (fn. 410) though long before then most inhabitants worked outside the village. (fn. 411)

MILLING

Two freehold corn-grist mills were recorded in the 13th century, of which one (on the Montsorel fee) owed 2d. hidage and scutage, and the other (on the Despenser manor) 55. rent a year, paid to the Knights Templar of Cowley (near Oxford) as intermediate lords. (fn. 412) The Montsorel mill was not mentioned later, but the second (by the stream along the Fifield road) continued until the 19th century (fn. 413) By 1350 the rent was 65. 8d., paid directly to the lords of the Despenser manor, (fn. 414) and in the 16th and early 17th century the double mill and attached mill house were usually let for 21 years at £7 6s. 8d., with substantial (though varying) entry fines. (fn. 415) In the 16th century it included both malt and wheat mills. (fn. 416)

After the Crown's sale of Ewelme manor the mill passed to various owners, who let it to local millers. (fn. 417) By 1673 it was a triple mill, (fn. 418) and in the 19th century a gabled two-storey house abutted the mill buildings. (fn. 419) By then, however, lessees generally occupied a larger house across the road, using the 'mill cottage' for employees or storage. (fn. 420) In the 1840s James Ashby (d. 1849), mealman, held the mill with both houses and 36 a. from Thomas Bishop Greenwood, (fn. 421) whose family moved to Ewelme as resident farmers and millers in the 1850s. (fn. 422) Though the mill cottage burned down in 1881, (fn. 423) the mill itself apparently continued under John Slade; (fn. 424) it was finally demolished in the 1890s, when the watercress beds were extended along the millstream. (fn. 425)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages