Pages 69-86

A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Originally published by Oxford University Press for Victoria County History, Oxford, 1981.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Gloucestershire. All rights reserved.

In this section

Fairford

FAIRFORD, which grew up at a crossing of the river Coln 13 km. east of Cirencester, was a market town and borough by the 12th century. The town, situated in an area of sheep-farming, prospered in the early 14th century and considerable growth followed a revival of its economic fortunes in the late 15th century. At that time John Tame, a sheepfarmer and wool-merchant, began rebuilding the church, which became famous for its stained-glass windows. Later the town, whose economy depended partly on its position on major routes, was primarily a market and shopping centre of local importance. In the 18th century there was some roadside building east and west of the town which in the 20th century was developed as a residential area.

The ancient parish, which covers 1,624 ha. (4,012 a.) and touches in the south-west the boundary of Wiltshire, is irregular in shape with a peninsulated part extending south-eastwards across flat meadow land near the river Coln. The river bisects the parish from north to south before turning south-eastwards to form part of the southern boundary. Elsewhere the boundaries follow the river and the Droitwich—Lechlade salt-way on part of the north, water-courses on the south and east, and field boundaries. (fn. 1) The land falls gently from 122 m. in the north to 76 m. in the south-east. The river valley lies on the Great Oolite or Forest Marble but elsewhere the land is formed by cornbrash or, in the south, by Oxford Clay. (fn. 2) The clay is overlaid in places by gravel beds which were used for road repairs by 1770 (fn. 3) but large-scale excavation did not begin until 1944 when, during the construction of Fairford airfield in Kempsford, pits were opened by the Whelford road. (fn. 4)

The river divides the parish into the tithings of Milton End, to the west, and East End, in each of which there were open fields and commons until the inclosures of the 18th century. Meadow land and pasture is found by the river, especially in the southeastern part, where agricultural land has disappeared since the mid 20th century to make way for the gravel workings which have changed the character of the countryside; some disused workings have been landscaped and adapted for recreation and nature conservation. (fn. 5) In the north Lea wood, the principal area of woodland, was mentioned in 1592 (fn. 6) and covered 65 a. in 1840 when the parish had a total of 148 a. of woods, (fn. 7) including later-18th-century plantations in Fairford park immediately north of the town. (fn. 8) Andrew Barker inclosed the park around his new manor-house in the late 17th century, (fn. 9) and by 1763 an obelisk had been built to terminate a view from the house through a deer-park which had been created in the park-land to the north. (fn. 10) In the 1780s the park was landscaped by William Eames (fn. 11) and enlarged, after a road diversion east of the river, (fn. 12) to include c. 200 a. (fn. 13) In the deer-park, which covered 54 a. in 1840, (fn. 14) an American Air Force hospital was laid out during the Second World War, after which its buildings housed a centre for Polish refugees. (fn. 15) The huts had been demolished by 1977.

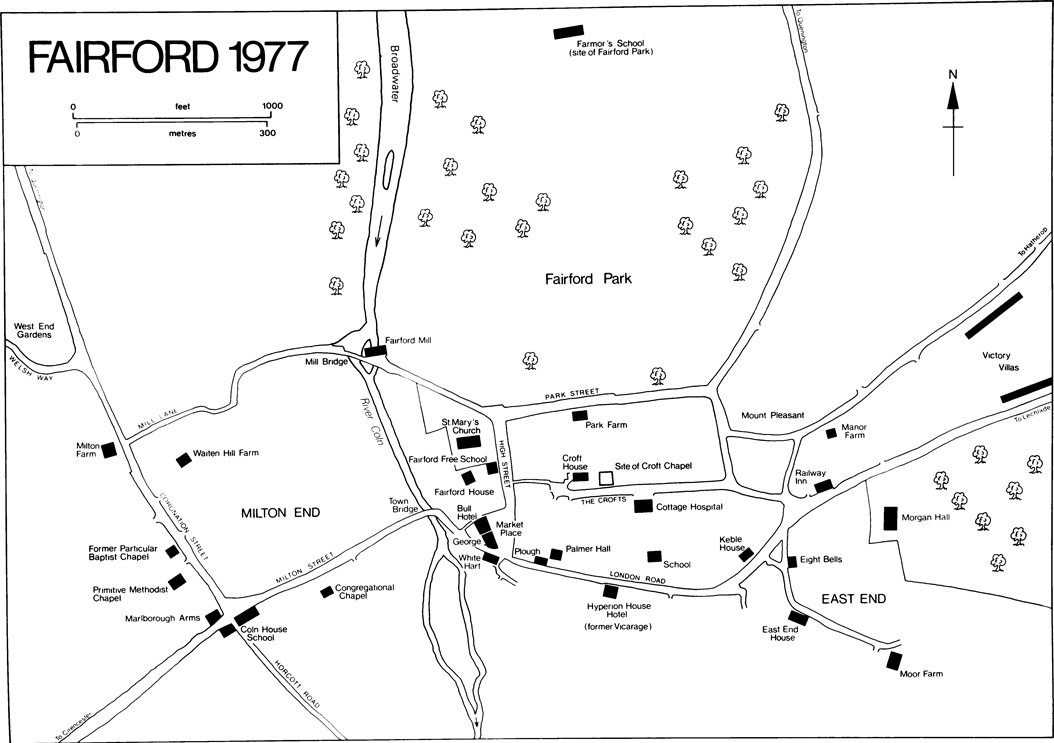

Fairford 1977

The Coln has long been known for its trout. (fn. 16) A fisherman lived in Fairford in 1381 (fn. 17) and an emblem of that trade is carved on the church tower. The fishing rights were let with the demesne from the late 15th century (fn. 18) but in the early 17th Fairford inhabitants had by custom a day's fishing at Whitsuntide. In the mid 1680s Viscount Weymouth, lord of Kempsford manor, claimed fishing rights in the river south of the town. (fn. 19) By the late 17th century the course of the river above the town took in a mill leat. (fn. 20) In the 1780s that stretch of the river was made into a feature of the park, being formed into Broadwater, which contains two islands and is spanned at the southern end by an 18th-century bridge. (fn. 21) The cascade feeding it had been constructed by 1757. (fn. 22)

The parish is named from a ford across the Coln, (fn. 23) which was entered by the Cirencester—London road at a point where a bridge had been built by the late 12th century. (fn. 24) The bridge had 4 stone arches when Leland saw it in the early 1540s (fn. 25) but has been rebuilt several times. (fn. 26) The road, for the repair of which members of the Tame family made bequests in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, (fn. 27) was turnpiked between Cirencester and St. John's Bridge in Lechlade in 1727. (fn. 28) West of the Coln it was joined by the Gloucester—London road, which remained important in the late 18th century (fn. 29) and was known as the Welsh way from the Welsh drovers who followed it. An alternative way into the town from the Gloucester road was provided by Mill Lane which by the early 18th century crossed the river by a substantial bridge. (fn. 30) East of the river a road to Eastleach has disappeared since 1770 and the Quenington road (fn. 31) was diverted eastwards in 1785. (fn. 32)

The town has had an important role in servicing road traffic: in 1699 a stage-coach service to Gloucester called there and in 1713 Cirencester coaches. (fn. 33) The town had a post office by 1729. In 1754 a Fairford man started a fortnightly stagewaggon between Gloucester and Oxford with a weekly service to Gloucester, and in 1781 a firm of carriers was operating between Gloucester and London. (fn. 34) In the later 18th century coaches running between Cirencester and London and between Bristol and Oxford served the town, on which several other services were based. (fn. 35) In 1873 the East Gloucestershire Railway Co. opened a branch line from Witney (Oxon.) (fn. 36) to a terminus east of the town. (fn. 37) The line closed in 1962. (fn. 38)

Early evidence of settlement in the parish is provided by a pagan Saxon cemetery north-west of the town. (fn. 39) The town had evidently been established at the river crossing by the mid 9th century (fn. 40) and the lords of the land exploited the commercial possibilities offered by that position before a royal grant of markets in the early 12th century. (fn. 41) By the end of that century a borough had been laid out east of the crossing (fn. 42) where a triangular market-place stretched south of the main road, which originally ran due east from the bridge along the lane called the Crofts. The area of burgages, which numbered 68 in 1307, (fn. 43) included a street running ESE. from the southern apex of the market-place and the eastern side of High Street, which ran northwards from the market-place to the church. The market-place was reduced in size by infilling of the western and, to a much lesser degree, eastern parts; that may possibly have occurred during the economic revival of the town which had begun by the late 15th century. Later the main road was diverted along a road from the town bridge to the southern end of the marketplace and the road further north disappeared. At the same time the road leading ESE., called Vicarage Street in 1662 (fn. 44) and later London Road, replaced the Crofts as the through route. Park Street, running eastwards from the northern end of High Street and known until the late 19th century as Calcot Street, (fn. 45) was recorded in the later 16th century. (fn. 46)

The old part of the town appears to have been largely rebuilt in the later 18th century and the 19th but one house north of London Road contains a 14th-century doorway. South of the market-place the White Hart, with a jettied upper storey, probably dates from the 16th century or earlier. West of the market-place the George, which retains a timber-framed upper storey, is also of an early date, as is the Bull to the north, which has been enlarged at several rebuildings. East of the market-place is a substantial mid-18th-century house. The former free school is also of that date. Seven cottages north of Park Street, which were in ruins by 1754, (fn. 47) were evidently replaced by the row built at the end of the 18th century. In High Street, where one building retains some 17th-century features, are two buildings rebuilt in Gothic style, one as a police station and petty sessional court in 1860 (fn. 48) and the other, a bank, in 1901. (fn. 49) Other 19th-century buildings include, south of London Road, the Hyperion House hotel, formerly the vicarage, and, south of Park Street, Park Farm, near which some houses were built in 1977.

South of the church Fairford House, which has a main, late-18th-century, front of five bays with central entrance and pediment, was greatly extended to the north in the 19th century. The other principal residence is Croft House, north of the Crofts. The central portion of the south front is a small three-bay house of the 18th century. Additions made for Jonathan Wane by Richard Pace in 1826 consisted of single-storey bow-fronted extensions to the south elevation and a new staircase hall and service range behind. (fn. 50) The house, which was the home of the landowner Robert S. Mawley in 1851, (fn. 51) passed to Albert Iles (d. 1863), whose wife Ellen (fn. 52) made it a private asylum for 4 women in 1866 when the bowfronted extensions were raised to two storeys. (fn. 53) It reverted to domestic use in 1893. (fn. 54) In a corner of the extensive gardens is an early-18th-century gazebo.

West of the river in Milton End, which was mainly built as a roadside suburb of cottages and small houses in the 18th century and later, (fn. 55) the oldest surviving building is a 17th-century house with three gables north of Milton Street, the Cirencester road. A large green, which apparently extended along both sides of the Gloucester road and was part of the Milton End common, was probably used by the Welsh drovers to pasture their cattle when stopping at the town. The green, much of which was evidently inclosed by an agreement of 1633, (fn. 56) was represented in 1977 by a small area east of the road. Building along the road had begun by the later 18th century. (fn. 57) It was named Coronation Street to commemorate Queen Victoria's coronation. (fn. 58) Most buildings in Milton End date from the 19th or early 20th century, including a house in the western angle of Coronation Street and the Cirencester road which was restored by Arthur Charles King-Turner. (fn. 59) Milton House, north of Milton Street, which belonged under long lease to William Thomas (d. 1859), Baptist minister of Maiseyhampton, (fn. 60) and was the home of professional men in the later 19th century, (fn. 61) was demolished after 1911. (fn. 62) Milton Farm, north-west of Milton End, dating from a mid-19th-century rebuilding, may occupy the site of the house recorded at Middleton c. 1100. (fn. 63) Waiten Hill Farm east of Milton Farm was rebuilt in 1894. (fn. 64) At Westend Gardens, which in 1880 included several buildings by the Quenington road, (fn. 65) an ornamented wall around a late-19th-century house may have been reset.

East End, a scattered group of houses around a green on the London road, includes substantial dwellings built by the wealthier inhabitants in the 18th century. To the east Morgan Hall, presumably the messuage called Bakers in 1590 and part of a leasehold estate which passed to the Morgan family and was sold by Robert Morgan to John Raymond in 1775, (fn. 66) includes a long range with three short western wings. A block of four bays was added to the east in the later 18th century when the older part was refaced. (fn. 67) In 1838 the park east of the house, which was then called Fairford Lodge, included c. 16 a. (fn. 68) South of the green an early-17th-century house survives in the east wing of Eastend House, the main part of which, added in the late 18th century, has three storeys and a main, south front of three bays. In 1901 a two-storeyed range was added to the west of the main front and behind it a new entrance hall. (fn. 69) North of the London road Keble House was built with two storeys and attics in the later 18th century for the Keble family, prominent in local affairs since the late 15th century. (fn. 70) From the late 1780s it was the home of John Keble, vicar of Coln St. Aldwyns (d. 1835), (fn. 71) whose son John (1792–1866), the Tractarian, lived there in 1838. (fn. 72) The house, which by 1840 was occupied by Charles Cornwall, still belonged to the Keble family in 1977 when part was let as a separate dwelling. To the north-east is a substantial 17th-century house with 19th-century bay-windows. By 1840, when it was the Baptist manse, it had been replaced as a farmhouse by the 19th-century Manor (formerly Eastend) Farm to the north-east. (fn. 73) In the south-east Moor (formerly Beaumoor) Farm dates from the 18th century. A row of cottages built south-west of Keble House c. 1870 (fn. 74) has the same stucco decoration as cottages north of Eastend House, some of which were derelict in 1977. A pair of estate cottages east of the green was built in 1907. (fn. 75)

To the north the area between the Quenington and Hatherop roads was developed from the late 1780s. The main residence, Mount Pleasant House, is an early-19th-century building with a south front of three bays. The original plan of Mount Pleasant Buildings to the east, built in 1835 by Thomas Jones, contained 16 cottages in four identical rows, one of which was rebuilt as three dwellings after 1873. (fn. 76) Another row was derelict in 1977. In the 20th century the town has been enlarged considerably by council and private building, particularly between the London and Quenington roads in East End. Council building, which began there with Victory Villas, completed in 1921, included a few houses built in 1947 nearer the town centre south of London Road. Some private housing had been provided at Westend Gardens by 1959 when it was said that 145 houses had been built recently in the town. (fn. 77) In the 1960s private building continued in those three areas and bungalows were built south of Milton Farm. (fn. 78)

There are few outlying buildings. At Long Doles in the south-eastern corner of the parish a farmhouse, which had been built by 1770 (fn. 79) and was part of the leasehold property of Joseph Cripps in 1840, (fn. 80) had been destroyed by fire by 1940. (fn. 81) The outbuildings of Leafield Farm in the northern part of the parish include a long, early-18th-century range of cartsheds and stables. South-west of the town at Burdocks a cottage, which in 1838 belonged to William Thomas's leasehold estate, (fn. 82) was replaced in 1911 by a large house, in the Queen Anne style, designed for J. Reade by Guy Dawber. (fn. 83)

In 1327 81 inhabitants were assessed for the subsidy (fn. 84) and in 1381 at least 180 for the poll tax. (fn. 85) In 1551 c. 260 communicants lived in the parish (fn. 86) and although in 1563 there were said to be only 27 households (fn. 87) there were 220 communicants in 1603 (fn. 88) and 100 families in 1650. (fn. 89) The population rose from about 660 c. 1710 (fn. 90) to about 1,200 by c. 1775. (fn. 91) From 1,326 in 1801 it increased to 1,859 by 1851 but then fell to 1,654 by 1861, mainly because of the removal of paupers from the private asylum, described below. It had dropped to 1,404 by 1901 and 1,347 by 1921. In 1951, following the establishment of the airfield in Kempsford and the refugee camp in Fairford park, it was at a peak of 2,439. After falling to 1,602 by 1961 it had risen to 1,804 by 1971. (fn. 92)

The parish maintained a fire-engine by 1783 (fn. 93) and for the fire brigade formed in 1867 a second-hand machine was bought. (fn. 94) The town was lit by gas supplied by a company established in 1852 (fn. 95) with works south of the market-place (fn. 96) and taken over by the Swindon company in the late 1930s. (fn. 97) Electricity, which had been brought to the town by the Wessex Electricity Co. by 1931, (fn. 98) was not applied to street lighting until 1970. (fn. 99) A drainage system built for the town centre in 1905 was extended after the Second World War. (fn. 100) In 1920 the town's water-supply came from a spring at the old mill north-west of the church (fn. 101) but in 1943 the War Department built a new system from the cascade feeding Broadwater. (fn. 102) A cottage hospital which opened in 1867, north of Park Street, (fn. 103) moved in 1887 to a new brick building on the site of the parish workhouse in the Crofts. (fn. 104)

In 1419 an inn was recorded in Fairford (fn. 105) where there were at least three in 1563 (fn. 106) although only two innkeepers were listed in 1608. (fn. 107) By the late 17th century road-traffic was served by several inns around the market-place. (fn. 108) Seven innkeepers were licensed in 1755 (fn. 109) and twelve in 1891. (fn. 110) The Swan, which had opened on the east side of the marketplace by 1610, (fn. 111) was used for assemblies (fn. 112) and was the calling place of Cirencester and Gloucester coaches. (fn. 113) It closed in the later 18th century after the property had been divided. (fn. 114) The Bull, which had opened by the mid 17th century (fn. 115) and was used for meetings by 1730, was the chief inn of the town by the late 18th century when it was used for concerts and petty sessions. (fn. 116) With the George, recorded from 1634, (fn. 117) it catered for coaches (fn. 118) and in both inns and in the White Hart, which had opened by 1750, (fn. 119) the parish officers met in the later 18th century. (fn. 120) The inns remained at the centre of the town's social life well into the 19th century, the George being used for balls in the early 1840s. (fn. 121) The Red Lion, north of Milton Street, was recorded in 1740 (fn. 122) but had closed by 1767. (fn. 123) The sites of the Cross Keys, opened by 1754 and rebuilt as a private house c. 1790, and the Hare and Hounds, where the parish officers met from 1777, are not known. (fn. 124) East End had the Eight Bells by 1863. (fn. 125) The Bull Tap, south-east of the town bridge and recorded in 1876, (fn. 126) was rebuilt as a private house in the 1970s. (fn. 127) In 1977 the George, Bull, White Hart, and Eight Bells remained open with the Marlborough Arms in the Cirencester road, the Plough inn in London Road, and the Railway inn in East End.

Parish friendly societies were recorded between 1750 and 1906. (fn. 128) A mechanics' institute with reading-rooms, founded by 1856, has not been traced after 1863 (fn. 129) but in the late 1930s there was a reading-room, situated next to the George. (fn. 130) In the mid 19th century Croft Hall was built south of the Crofts for public meetings (fn. 131) but in the early 20th it became a private house. (fn. 132) Another building at the west end of the town was used for concerts at the end of the 19th century. (fn. 133) Palmer Hall, the gift of Col. A. J. Palmer, opened in London Road in 1936 and became the chief centre for social events. (fn. 134) There were several printers in the town in the later 19th century (fn. 135) and in 1877 the Fairford Herald was being published. (fn. 136)

An annual carnival, inaugurated in the 1890s to raise money for the cottage hospital, (fn. 137) was held until c. 1936. (fn. 138) By the late 1960s a traction engine rally had been started. (fn. 139) A cricket club had been formed by 1902 with grounds in the park at the eastern end of Park Street, (fn. 140) and a bowling club by 1935 with a green east of Eastend House. (fn. 141) Fishing, sailing, and water-skiing clubs made use of the old gravel pits in 1977.

Alexander Iles, who was caring for insane people by 1821, founded the Retreat, a private asylum in Milton End, the following year. (fn. 142) It was extended in 1829 when it had 20 patients and the number increased considerably, mainly by the admission of paupers, some of whom were employed on the Iles family's farm or in gardening or housework. (fn. 143) There were 187 patients in 1851, (fn. 144) but 104 were transferred to the Wiltshire and Worcestershire county asylums the following year and 21 to the Gloucestershire asylum in 1859. The Retreat, which had 42 patients in 1872, (fn. 145) was sold to A. C. King-Turner in 1901 (fn. 146) and closed c. 1944. (fn. 147) The buildings housed a riding school until bought by the county council, which in 1949 opened Coln House School there for educationally subnormal children. (fn. 148)

Royal visitors to Fairford have included Edward I in 1276 (fn. 149) and Henry VIII in 1520. (fn. 150) In 1830 agricultural labourers rioting in the surrounding countryside destroyed threshing-machines on the premises of two Fairford machine-makers. (fn. 151)

The politician Wills Hill, earl of Hillsborough (1718–93), was born at Fairford and took the name of the town for his viscounty in 1772. (fn. 152) Also born in Fairford were the missionaries John Thomas (1757–1801) and Abraham Cowley (1816–?87). (fn. 153)

Manors and Other Estates

Gloucester Abbey apparently had an estate at Fairford when it granted ten 'cassati' of land there to Burgred, king of the Mercians 852–74, in return for certain liberties. (fn. 154) Before the Conquest the manor of FAIRFORD, which comprised 21 hides, including land in Eastleach Turville, was held by Brictric son of Algar. It was granted to the Conqueror's queen Maud, at whose death in 1083 it passed to the Crown, from whom the Fairford land was held by Humphrey in 1086. (fn. 155) The manor, which had been granted to Robert FitzHamon by 1100 (fn. 156) and was assessed at 1½ knight's fee in the early 14th century, (fn. 157) descended with Tewkesbury manor as part of the honor of Gloucester until 1314, (fn. 158) except that Hawise, widow of William, earl of Gloucester (d. 1183), retained rights in Fairford where she made a grant of a burgage. (fn. 159)

Fairford had passed to Hugh le Despenser in right of his wife Eleanor, sister and coheir of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester (d. 1314), (fn. 160) by 1320 when they granted the manor to the elder Hugh le Despenser. (fn. 161) In 1327 the Crown granted it to Alice, widow of Edmund, earl of Arundel, for her maintenance, but it was restored to Eleanor the following year. (fn. 162) She retained it until her death in 1337 and her son and heir Hugh le Despenser, (fn. 163) Lord le Despenser (d. 1349), was succeeded by his nephew Edward le Despenser, a minor. (fn. 164) Edward died in 1375 (fn. 165) and the manor was held in dower by his wife Elizabeth (fn. 166) (d. 1409). Her grandson Richard le Despenser died in 1414 leaving as his heir his sister Isabel, who married first Richard de Beauchamp, earl of Worcester, and second Richard de Beauchamp, earl of Warwick (d. 1439). (fn. 167) She settled the manor on feoffees before her death later in 1439 when she was succeeded by her son Henry, earl of Warwick. (fn. 168) Henry, created duke of Warwick in 1445, died the following year and Fairford passed with the earldom to his daughter Anne (fn. 169) (d. 1449) and then to his sister Anne. After the death of the elder Anne's husband Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, in 1471, Fairford was allotted to George, duke of Clarence, who had married Isabel, one of Warwick's daughters and coheirs. He forfeited his lands upon attainder in 1478 (fn. 170) and, as his son and heir Edward was a minor, the Crown leased the demesne the following year to John Twyniho and his son-in-law John Tame. (fn. 171)

John Tame (d. 1500) continued to farm the demesne after Henry VII's accession (fn. 172) when the manor was restored to Anne, dowager countess of Warwick, who made it over to the Crown. She regained some rights from 1489 until her death in 1492. (fn. 173) In 1532 John Tame's son Sir Edmund secured a lease of the demesne for 21 years (fn. 174) and after his death in 1534 his wife Elizabeth assigned it to his son Edmund, (fn. 175) who became a knight and died in 1544. The younger Sir Edmund's widow Catherine (fn. 176) married Walter Buckler and in 1547 the Crown granted them the manor in fee as part of an exchange. (fn. 177) Walter, later knighted and a privy councillor, (fn. 178) was dead by 1554 when Catherine settled the manor on herself and Roger Lygon, her third husband, and granted the reversionary right to her brother Sir Walter Dennis and his heirs. (fn. 179) Roger survived Catherine (fl. 1578) (fn. 180) and the manor had passed to Sir Walter's grandson Walter Dennis by 1587 when it was settled on his marriage to Alice Grenville. They quitclaimed it in 1590 to Sir Henry Unton and John Croke who sold it the following year to Sir John Tracy of Toddington. (fn. 181) Sir John was succeeded later in 1591 by his son John, who became a knight and by 1631 had made over the land to his son Sir Robert. (fn. 182) Sir John, who retained the manorial rights, (fn. 183) was created Viscount Tracy of Rathcoole in 1643 but his estates were sequestered the following year. Sir Robert, his heir, (fn. 184) as a result of a debt incurred for delinquency, sold the manor in 1650 to Andrew Barker. (fn. 185)

Andrew (d. 1700) (fn. 186) was succeeded by his son Samuel (fn. 187) who died in 1708 leaving two daughters, Elizabeth (d. 1727) and Esther. Esther, who married James Lambe of Hackney (Mdx.) (fn. 188) (d. 1761), (fn. 189) left the estate at her death in 1789 to her nephew John Raymond on condition that he took the additional name of Barker. John (d. 1827) was succeeded by his son Daniel Raymond-Barker who died later that year leaving as his heir his son John Raymond Raymond-Barker (d. 1888). His son Percy Fitzhardinge Raymond-Barker (d. 1895) was succeeded by his son Reginald, (fn. 190) whose estate covered over 3,157 a. in 1914. (fn. 191) In 1945 his representatives sold the estate of c. 2,400 a. to Ernest Cook who included it in the endowments of the Ernest Cook Trust, an educational charity which he established in 1952. In 1977 the trust owned c. 1,320 ha. (c. 3,263 a.) in Fairford and parishes to the north. (fn. 192)

Richard Neville, earl of Warwick (d. 1471), is said to have had a manor-house called Warwick Court north of the church. (fn. 193) John Tame and his son Edmund rebuilt the house, which apparently had ranges west and south-west of the church. (fn. 194) In 1520 Henry VIII visited the house (fn. 195) which was the home of Edmund's wife Elizabeth (d. 1545) (fn. 196) and possibly of Sir Robert Tracy in the 1630s. (fn. 197) It was partly demolished in the later 17th century. (fn. 198) Part called the Old Court, north of the church, included stables in the mid 18th century but was later demolished and the site taken into the churchyard. (fn. 199)

The building of Fairford Park was begun for Andrew Barker in 1661 by Valentine Strong (d. 1662) of Taynton (Oxon.) who was probably also the designer. (fn. 200) The house, 500 m. north of the town and incorporating masonry from the older house, (fn. 201) had main fronts of seven bays to the north and south and was set in extensive formal gardens. (fn. 202) It was altered for James Lambe (fn. 203) and it was probably for him that the gardens to the north were laid out in 'the wilderness way' with canals and serpentine walks adorned with statues, urns, and grottos east of the river. (fn. 204) The gardens were included in William Eames's landscaping of the park in the 1780s and part of the surviving walling is dated 1783. Sir John Soane carried out alterations to the interior of the house in 1789. (fn. 205) Some out-buildings to the west were demolished in the late 18th or early 19th century when the house was joined to a reorganized stable court by a two-storeyed range. The attics of the main block were possibly converted as a full third storey at that time. The house was empty for some time before 1889 (fn. 206) when it was let to tenants and in the early 20th century Col. Albert John Palmer lived there. (fn. 207) It was demolished in 1955, and in 1977 the stable court was used by the estate for offices and labourers' cottages. Of the lodges one at the west end of Park Street dates from the 19th century (fn. 208) but another, by the Quenington road west of the river, has been demolished. (fn. 209)

By 1216 Hugh de Chaworth had granted 1 hide of land in Milton End, held from Fairford manor, to Bradenstoke Priory (Wilts). (fn. 210) The priory's property, which after the Dissolution was called HYDECOURT manor, (fn. 211) was granted in 1545 to John D'Oyley and John Scudamore. (fn. 212) They sold it to Sir Walter Buckler and his wife Catherine in 1548, (fn. 213) after which it passed with Fairford manor. (fn. 214)

By 1506 the Knights Hospitallers held property in Fairford as an adjunct of Quenington Preceptory. (fn. 215) The property of Studley Priory (Oxon.), granted to John Croke in 1540, (fn. 216) has not been identified but it may have been united with Fairford manor in 1590.

By 1291 Tewkesbury Abbey held rents of assize in Fairford, (fn. 217) and land which escheated to the abbey at the death of Sir John Worthe in the early 15th century probably became part of the vicar's glebe. (fn. 218) The abbey's rectory estate, comprising the grain tithes, was leased in 1533 for 21 years to Sir Edmund Tame, his wife Elizabeth, and son Edmund. (fn. 219) In 1541 it was granted to the dean and chapter of Gloucester cathedral (fn. 220) who c. 1550 leased it for 90 years to William Thomas. He granted the lease c. 1558 to Roger Lygon and his wife Catherine, and Roger conveyed it to his nephew George Lygon. After George's death action was taken in 1594 against his brother and executor, Henry, to secure the lease for George's grandson Robert Oldisworth, a minor, (fn. 221) but the estate was being farmed by Richard Lygon in 1603. (fn. 222) William Oldisworth, described in 1660 as the impropriator, (fn. 223) took a lease for 21 years the following year. Thereafter the estate was leased to him and his successors, the lease being renewed every few years. William died in 1680 and James Oldisworth (d. 1722), rector of Kencot (Oxon.), was succeeded by his daughter Muriel Loggan (d. 1754). (fn. 224) The lease was then held by trustees under her will (fn. 225) until 1781 when John Oldisworth came of age. (fn. 226) He sold the lease to John Raymond-Barker in 1794 and it then passed with Fairford manor. (fn. 227) In 1840 the rectorial tithes were commuted for a corn-rent-charge of £513 10s. (fn. 228) and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, who acquired the freehold in 1855, (fn. 229) sold it to the trustees of the Fairford estate in 1858. (fn. 230)

Economic History:

Agriculture

The demesne of Fairford manor, which was given over to corn production in the late 1230s, (fn. 231) included 610 a. of arable, 70 a. of meadow, and 6 several pastures in 1307. (fn. 232) By c. 1327 the arable land in hand had been reduced to 574 a. and there were over 105 a. of meadow in demesne. (fn. 233) The lord's stock in the 1320s included 3 ploughs and 100 qr. of barley, 30 qr. of wheat, 14 qr. of oats, and some hay. He also owned at least 226 sheep there, (fn. 234) and in 1381 several shepherds lived in the town. (fn. 235) In the late 15th century the manorial demesne was farmed by John Tame, who employed at least four shepherds on his estates, (fn. 236) and his son and apparent successor as demesne farmer, Sir Edmund, owned at least 500 sheep at his death in 1534. (fn. 237) Bradenstoke Priory's property, which in 1291 included two plough-lands, (fn. 238) had been leased to the younger Edmund Tame by 1538. (fn. 239)

In 1066 Fairford manor, including part of Eastleach Turville, supported 56 villani and 9 bordars with 30 plough-teams. (fn. 240) About 1100 Robert FitzHamon granted a tenement by the service of supplying fowls. (fn. 241) In 1307 when 2 plough-lands were held by that service there were 30 other free tenants outside the borough holding by cash rent. Three held yardlands and six had small, unspecified holdings; the other tenements varied in size and included a water-mill and a weir. (fn. 242) In the late 15th and early 16th centuries a freehold estate of over 66 a., apparently acquired by John Langley of Siddington in the early 1440s, was held under the manor. (fn. 243) In 1307 there were c. 75 customary tenants including 41 yardlanders, c. 10 half yardlanders, and 11 tenants with 6 a. each. Each yardland owed 4 weekworks, ploughing- and harrowing-services, and 8 bedrepes. There were also 13 cottagers owing cash rent, and the customary tenants paid £8 for tallage, and cash or kind for other customary payments. (fn. 244) By 1314 the yardlander's week-work had been increased to 5 days, excepting feast days and the weeks of the three main festivals. (fn. 245) About 1327, although the demesne arable had been reduced, 42 yardlanders owed week-work but gave cash for their bedrepes. There were also 9 half-yardlanders and 16 cottagers. (fn. 246)

There is evidence in the collection of rents of a general impoverishment among the manor's free and customary tenants before 1482, and the large amount of land apparently occupied by tenants at will in the later 1480s, when they paid £17 5s. 6d., suggests a difficulty in getting long-term customary tenants. The free rents collected outside the borough then comprised 14s. 4d., including 4s. for land in Chedworth. (fn. 247) In the later 16th century Roger Lygon and his wife Catherine created several copyholds and after Roger's death the tenants initiated a Chancery suit to establish their rights. (fn. 248) From 1590 the lords of the manor granted leases, some of large holdings, for terms of up to 2,000 years under which much property in the parish was held, (fn. 249) but some copyholds remained in 1633. (fn. 250)

In 1375 a third of the arable demesne lay fallow, suggesting a three-field system. (fn. 251) By the 17th century there were two open fields each in East End and Milton End tithings which were not, however, completely distinct agrarian units, for Milton End property included common rights in East End. (fn. 252) East End in 1597 had a home and a further field, the latter on the boundary with Hatherop, (fn. 253) and Milton End in 1610 a north field and a field on the boundary with Maiseyhampton, (fn. 254) presumably the south field mentioned later. (fn. 255) Meadow land and pasture lay near the river and more especially towards Long Doles in the south-eastern corner of the parish (fn. 256) where a lot meadow, possibly that recorded in 1597, (fn. 257) lay across the Whelford road at the parish boundary. (fn. 258) Other meadows lay west of the river above the town bridge.

The two principal commons were at opposite ends of the town. (fn. 259) The Moor, recorded in 1610 (fn. 260) and possibly where meadow land had been granted c. 1100, (fn. 261) was bounded by the Coln south-east of the town. (fn. 262) To the east and south-east were commons called the Horse common, the Lower common, and the Cow common. (fn. 263) The Milton End common, parts of which, including the great green, were inclosed by Sir Robert Tracy under an agreement of 1633, (fn. 264) was represented in the mid 18th century by the Cow common, north of the Cirencester road, and a small area of waste land to the west. The latter was divided into small parcels in which some commoners had several rights to wood and furze. Milton End was finally inclosed in 1755 by agreement between James and Esther Lambe, who held 737 a. of openfield land, and their leasehold tenants, who held the remaining 73 a. Under the agreement one tenant was allotted a small piece of the green and 11 others 97 a. in the south field for their open-field and waste land and common rights. (fn. 265) East End was inclosed in 1770 by agreement between Esther Lambe, the vicar, the other landowners, and leaseholders. Under the agreement, which affected 1,657 a., Esther Lambe received 742 a. and the vicar 28 a. for his glebe and common rights. Elizabeth Morgan, Henry Brown, Sarah Brown, and Thomas Cripps received 511 a., 150 a., 75 a., and 59 a. respectively. Twelve others were allotted up to 14 a. each. There were left as commons 12 a. of the Moor, 14 a. of the Cow common, and a ground called the Crofts (fn. 266) which had evidently been inclosed by 1828. (fn. 267)

In 1831 labour was employed by ten of twelve farmers in the parish (fn. 268) where the largest farms had been formed on the Fairford estate. In 1840 when 691 a., including land farmed from Park farm, were in hand there were farms of 1,040 a. (corresponding to those later called Milton and Farhill farms), 555 a. (Manor farm), 383 a. (Leafield farm), 357 a. (Waitenhill farm), 171 a. (Moor farm), and 96 a. based on Waitenhills Barn. (fn. 269) In 1914 there were seven farms on the estate, namely Manor (631 a.), Milton (569 a.), Waitenhill (522 a.), Park (483 a.), Farhill (387 a.), Leafield (376 a.), and Moor (189 a.). (fn. 270) Park and Farhill were farmed together in the early 20th century. (fn. 271) Several of the 29 farmers returned in the parish in 1896 (fn. 272) worked smallholdings and nearly half of the 23 farmers returned in 1926 had less than 20 a. (fn. 273) In 1976 five smallholdings of under 20 ha. (50 a.), worked on a part-time basis, were returned together with seven larger farms of which two had over 300 ha. (741 a.). (fn. 274)

Corn and sheep husbandry were dominant after inclosure. In 1781 cereal crops were grown on 1,052½ a. (fn. 275) and by 1807 the flock of sheep on the home farm of the Fairford estate had been improved by the introduction of the new Leicester breed. (fn. 276) Arable land predominated over grassland in the mid 19th century; in 1866 2,137 a., cropped with cereals, roots, and grass seeds, were returned compared with 495 a. of permanent grassland. (fn. 277) Large flocks, numbering at least 2,727 sheep, were kept then and the rich meadow land made cattle-raising and dairying a significant part of local farming; a total of 357 cattle, including 44 milk cows, was returned. Pig-raising was also important then. (fn. 278) By 1863 allotment gardens had been laid out south of the Lechlade road (fn. 279) and in the later 19th century a market gardener lived in the parish. (fn. 280) In the later 19th century and early 20th the area returned as under cereal crops fell slightly but the area of recorded permanent grassland nearly trebled. The later 19th century saw an expansion in sheep-farming and dairying but in the early 20th more beef, as well as dairy, cattle were introduced; 581, including 151 milk cows, were returned in 1926. (fn. 281) In the mid 1970s four of the main farms were devoted principally to cereal production, chiefly barley and wheat, and two others to dairying. Cattle-raising remained an important part of local farming but sheep-farming and pig-rearing had ceased to be significant. (fn. 282)

Mills

The three mills belonging to Fairford manor in 1066 (fn. 283) presumably occupied the site of the mill in which c. 1100 Robert FitzHamon granted his fowler the same liberty as he enjoyed. (fn. 284) In 1296 the site included a fulling-mill (fn. 285) but in 1307 there were apparently only corn-mills, two in demesne and one, with the suit of Milton End, held at fee farm. (fn. 286) From the late 17th century a mill was recorded where Mill Lane crossed the Coln. (fn. 287) In the mid 19th century it was worked by members of the Tovey family. (fn. 288) It went out of use shortly after 1910 (fn. 289) and was converted to domestic use. The building, which dates from the 17th century, incorporates a wing dated 1827 and alterations made in 1841. (fn. 290)

Trade and industry

By 1135 a market town had been created at Fairford, which thrived later as a centre for retailers and craftsmen. In the 14th century the town, in an important wool-growing region, enjoyed considerable prosperity. In 1307 there were 68 burgages (fn. 291) and about twenty years later the borough rents were worth £5 12s. 2½d.; (fn. 292) in 1334 Fairford had a higher assessment for tax than Lechlade or Tetbury. (fn. 293) The wealthier inhabitants in 1327 included a baker, a chapman, a skinner, a smith, and a wool-monger, while Robert Hitchman and William Sparks, apparently the two wealthiest, were possibly merchants. (fn. 294) Thomas Hitchman and Robert Sparks were among at least four merchants living in the parish in 1381 when there were several butchers, a cobbler, a tailor, a tanner, a tiler, and a smith. The presence then of at least two hostelers is early evidence for the town's role in servicing road traffic. (fn. 295) By the 1480s, when the free borough rents realized only £2 0s. 9d. and the lord of Fairford retained several burgages in hand because of a lack of tenants, the town had suffered a decline, the reversal of which was apparently stimulated by the activities of members of the Tame family, (fn. 296) presumably descendants of that John Tame of Fairford appointed in 1416 to collect a subsidy in the county. (fn. 297) John Tame (d. 1500), the principal inhabitant in the later 15th century, who had inherited several burgages from his father, also John, acquired and rented much property in the town (fn. 298) and surrounding countryside (fn. 299) where he became a sheep-farmer on a considerable scale. Although he had property in Cirencester, he centred his business on Fairford where he rebuilt the church, and his son Edmund, who completed that work, became sheriff for the county three times and was knighted in 1516. (fn. 300)

In the late 13th century Fairford had a woollen textile industry based on one of its mills but cloth manufacture was never of great significance although Daniel Defoe described Fairford as one of the county's principal clothing towns in the early 18th century. (fn. 301) Edward Byget from Picardy, who was living in the town in 1436, may have worked in the cloth industry or wool trade (fn. 302) and later-15th-century inhabitants may have included a fuller and a weaver, (fn. 303) but the cloth industry, represented by two weavers in 1608, was evidently small in scale. (fn. 304) A cloth worker was recorded in 1693 (fn. 305) and weavers were living in the parish in the early 19th century. (fn. 306) In the late 18th and early 19th centuries a few inhabitants following the trade of wool-stapler employed combers and spinners. (fn. 307) A flax-dresser lived in the town in the early 1790s. (fn. 308)

By 1608, when 26 tradesmen were recorded in Fairford compared with 28 men employed in agriculture, the town was primarily a centre for retail and service trades. There were 4 butchers, 4 smiths, 3 tailors, 2 innkeepers, 2 mercers, 2 shoemakers, 2 wheelers, a carpenter, a cutler, a glover and a mason. (fn. 309) In the later 17th century the economic life of the town depended considerably on the servicing of road traffic (fn. 310) which, with the market and fairs, was its chief support in the early 18th century. (fn. 311) The inhabitants included a tobacconist in 1712, (fn. 312) a tallow-chandler in 1721, (fn. 313) a clock-maker in 1754, (fn. 314) a peruke-maker in 1769, (fn. 315) and a hairdresser, an iron-monger, and a stationer in the early 1790s. (fn. 316) The leather trades were well represented in the 18th century (fn. 317) and workers in the clothing trades included a staymaker in 1754. (fn. 318) In 1842 the town's tradesmen included 5 cobblers, 3 dressmakers, 2 straw hat makers, 2 chemists, a basket-maker, a wine and spirit merchant, and a coal merchant. (fn. 319) In the early 20th century several coal-merchants operated from the railway station (fn. 320) on the site of which a member of the Lockwoods Foods Group had a depot in 1977. The craft of blacksmithing survived until c. 1930 and that of wheelwrighting until the Second World War. (fn. 321)

Building trades have employed many people in the town, where there was a lime yard in 1590. (fn. 322) Glaziers, slaters, and masons were mentioned in the 18th century (fn. 323) and building firms from the mid 19th century, including Yells Bros. founded in Milton End by 1914. (fn. 324) Bricks, tiles, and drain pipes were made at Waiten Hills, west of the town, by the mid 1870s (fn. 325) and in 1977 Portcrete Ltd., a member of the Bath and Portland Group, occupied a site near gravel workings by the Whelford road. Agricultural machinery has been made in the parish since at least the early 19th century when John Savory (d. 1826) was described as a threshing machine maker. His son John (fn. 326) and Richard Rose both made machines in Milton End in the middle of the century. (fn. 327) In 1842 one inhabitant was described as a tinman. (fn. 328) In 1977 the inhabitants worked for local building firms or shops, at the Fairford R.A.F. base in Kempsford, or in Cirencester or Swindon.

A physician may have lived in Fairford in 1500, (fn. 329) and in the 18th century the professions were well represented. A Fairford man who took up surgery in 1697 was still in practice in 1735 (fn. 330) and several inhabitants later that century were surgeons and apothecaries. (fn. 331) The residents included an attorney, Alexander Ready (later Colston), in 1734 (fn. 332) and a land-surveyor in 1770. (fn. 333) By 1848 3 surgeons, 3 auctioneers, and a conveyancer were established in the town (fn. 334) and there was a bank by 1844. (fn. 335)

Market and fairs

Robert, earl of Gloucester and lord of Fairford manor, evidently levied tolls and stallage in a market in Fairford before his father Henry I granted their falconer Remphrey a market there on Tuesdays and Fridays. (fn. 336) The town was an established market for corn in the 1260s, (fn. 337) and the lord of the manor was holding the market and a fair there in 1287. (fn. 338) The fair, on the feast of St. James (25 July), was worth 5s. in 1307 when the market tolls were valued at 10s. (fn. 339) Their combined value of £2 6s. 8d. c. 1327 compared with the general prosperity of the town at that time indicates a relatively small volume of trade (fn. 340) but by 1375 another fair was held on Ascension day. (fn. 341)

Leland in the early 1540s described Fairford as a market town (fn. 342) but the market had possibly lapsed by 1672 when Andrew Barker had a grant of a Thursday market and fairs on 3 May, 28 July, and 1 November. (fn. 343) They were important in the town's commercial life at the beginning of the 18th century (fn. 344) but the July fair had been discontinued by 1755. Efforts to revive the market after it had lapsed were twice necessary during that year, providing further evidence of a decline of trade in the mid 18th century. (fn. 345) The market, which was mainly for cheese and corn (fn. 346) but was not much frequented c. 1775, (fn. 347) was held until c. 1860. (fn. 348) After the opening of the railway in 1873 a market for cattle was held every second Tuesday (fn. 349) but, together with the remaining fairs (held following the calendar change on 14 May and 12 November) (fn. 350) was discontinued in the late 1930s. (fn. 351)

Local Government

In 1221 Fairford was denied its wish to answer the eyre separately from the hundred. (fn. 352) The lord of the manor and borough, whose courts in 1246 included some called hundreds (fn. 353) and who in 1255 compelled Tewkesbury Abbey to answer at his Fairford court for matters arising in Rendcomb, Ashton Keynes (Wilts.), and elsewhere, (fn. 354) claimed view of frankpledge and right of gallows, pillory, and tumbril in 1287. (fn. 355) There was a prison at Fairford in 1248. (fn. 356)

In the 14th and 15th centuries the view for the manor and borough was held twice a year in their respective courts. (fn. 357) The borough had its own bailiff, recorded c. 1400, (fn. 358) and the foreign bailiff, mentioned in the later 1480s, possibly administered the rest of the estate, though a single annual account was then rendered for both manor and borough. (fn. 359) The lord of the manor exercised the view over several tithings outside the parish; Arlington and Eastleach Turville attended the Fairford court (fn. 360) but in the later 1480s separate courts were held in Marston Maisey (Wilts.) and Shorncote in Somerford Keynes (Wilts., later Glos.), the latter evidently also for Siddington and Norcott in Preston. (fn. 361) A roll survives for a session in 1633 of a Fairford court in which the view of frankpledge for borough, manor, and 'foreign' (then used to designate the tithings outside the parish), was held with a court baron. The court, which elected a constable and two wardmen for the borough and tithingmen for East End, Milton End, and the other tithings, also appointed a hayward and two surveyors of the fields in Fairford where it dealt with agrarian matters. (fn. 362)

The town was policed by two constables in the early 18th century (fn. 363) but by only one at the end of the century (fn. 364) when it had a crier. (fn. 365) A blind-house, the town lock-up, had been built by 1809 (fn. 366) and in 1838 there were pounds in East End and Milton End. (fn. 367) The churchwardens, recorded from the late 1480s, (fn. 368) numbered one in 1498 (fn. 369) but two by 1566. (fn. 370) From 1774, when their suviving accounts begin, until 1797 their expenses were ordinarily met by the church or parish lands charity; later they were met by the poor-rate until 1836. (fn. 371) The three surveyors of the highways, recorded in 1663, (fn. 372) contracted with a local man in the 1840s to repair the roads for periods of three years. (fn. 373)

Burdocks Barn south-west of the town was bought with charity money in 1757 for a pesthouse. (fn. 374) Let from 1836 when it comprised two cottages, (fn. 375) it had been demolished by 1905. (fn. 376) Three overseers administered poor-relief. Their accounts survive for the period 1774–1809, during which a surgeon and a midwife were retained, although in the early 19th century the former was paid only expenses, which included those of a mass innoculation in 1806. Parishioners were sent to Gloucester Infirmary. (fn. 377) In the late 1770s the church house was used as a poorhouse (fn. 378) but c. 1787 poorhouses, called Tinkers Row and containing six cottages, were built with charity money. From 1836 they were let. (fn. 379) To provide relief the parish purchased and maintained spinning wheels and put men to work digging stones. A salaried overseer was employed from 1788 until 1797 when a parish workhouse was opened in a converted barn south of the Crofts. The house, which had a salaried governor and in which the women spun flax and worsted, (fn. 380) had 23 inmates in 1803 when their work produced the sum of £37. (fn. 381) It was demolished after 1840 (fn. 382) and the stone used in the early 1870s for building the infant school. (fn. 383) In 1776, when 35 people received regular help, (fn. 384) the annual cost of poor-relief stood at £250. It rose to over £1,134 by 1813 but fell to £844 by 1815. In the late 1820s and early 1830s it averaged c. £930. Forty-one people received regular help in 1803, 67 in 1813, and 61 in 1815. (fn. 385) In 1849 the vestry agreed to finance the emigration of poor residents out of the poor-rate. (fn. 386) Fairford, which became part of the Cirencester union in 1836 (fn. 387) and remained in Cirencester rural district, (fn. 388) was included in Cots wold district in 1974.

Church

There was a priest on the manor before 1086 (fn. 389) and Fairford church was given by Robert FitzHamon, apparently before 1100, to the church of Tewkesbury. (fn. 390) Between 1181 and 1185 Tewkesbury Abbey was licensed to appropriate the benefice but it continued to appoint secular clerks. (fn. 391) During a vacancy in the abbey in 1216 the Crown presented to the living. (fn. 392) The abbey's licence was renewed in 1221 and 1230 (fn. 393) but the bishop opposed any appropriation of the living (fn. 394) until 1333 when a vicarage was ordained. (fn. 395) The living has remained a vicarage. (fn. 396)

Tewkesbury Abbey held the rectory and the advowson of the vicarage until the Dissolution, and in 1541 the Crown granted them to the dean and chapter of Gloucester cathedral. (fn. 397) Under a grant by the assignee of the dean and chapter Roger Lygon and his wife Catherine presented in 1559 and Roger alone in 1560. The dean and chapter presented in 1564 but granted away the next turn in 1576. (fn. 398) Roger Lygon was said to be patron in 1584 (fn. 399) but the patronage was in contention the following year when in the confusion Archbishop Whitgift collated to the living, thereby setting aside the presentation by a patron for the turn. George Lygon, one of the claimants, presented in 1586 and Robert Oldisworth in 1617. After the Restoration the dean and chapter exercised their right of patronage, (fn. 400) which they retained in 1977. (fn. 401)

The priest mentioned in 1086 held 1 yardland of the manorial demesne. (fn. 402) The tithes from 1 hide in Milton End, claimed by Gloucester Abbey for Kempsford church, were awarded between 1198 and 1216 to Fairford in return for two gold coins a year. (fn. 403) In 1233 the Crown, which held the manor in ward, granted the mill tithes to Tewkesbury Abbey. (fn. 404) In 1291 the abbey had a portion of £3 13s. 4d. for tithes. The rectory was then worth £20. (fn. 405)

The vicarage ordained in 1333 comprised the rectory house, ¼ yardland, and some tithes, including those of hay, flax, wool, lambs, and milk. (fn. 406) The vicar's glebe, which included 13 a. of arable and 2 a. of meadow in 1535, (fn. 407) lay in East End. In 1678 it comprised 14½ a. of open-field land and 8 a. of meadow, part of which had been granted as compensation for the hay tithes of some lot meadows. For the tithes of a corn-mill he received 4 nobles a year. (fn. 408) When East End was inclosed in 1770 the vicar was allotted 28 a. south-east of the town for his glebe and common rights (fn. 409) save for those in the Crofts, which had been commuted for a small piece of pasture by 1828. By then the glebe had been let out and the lord of the manor was paying the vicar £280 a year for the tithes on his estate. (fn. 410) The vicar's tithes were commuted for a corn-rent-charge of £398 10s. in 1840. (fn. 411) The glebe, on which allotments had been laid out by 1863, (fn. 412) was excavated following the sale of the gravel rights in 1976. (fn. 413)

The vicarage was worth £13 11s. 4d. clear in 1535 (fn. 414) and £50 in 1650. (fn. 415) By 1661 it had been augmented by a stipend of £20 from the rectory estate (fn. 416) and from 1739 the vicar also received £40 for sermons. (fn. 417) The value of the living rose from £120 in 1750 (fn. 418) to £505 by 1856. (fn. 419)

The vicarage house, which was in ruins by 1569 when the incumbent was non-resident, (fn. 420) had 12 bays in 1705. (fn. 421) The 18th-century house, south of London Road, (fn. 422) was occupied by a curate in the early 1820s; (fn. 423) it was rebuilt and enlarged in 1865. (fn. 424) It was sold in 1957 when a new vicarage was built in the Crofts. (fn. 425)

Ralph de Hengham, royal justice and pluralist, had become rector by 1294 (fn. 426) but Tewkesbury Abbey was contesting his incumbency in 1298. (fn. 427) Ralph had resigned by 1304 and his successor, Stephen Malore (fn. 428) (d. by 1323), (fn. 429) was licensed to absent himself in 1319. (fn. 430) The vicar Thomas Green, who in 1402 was dispensed to let the benefice at farm during any absences in the following ten years, was a pluralist, as were many of his successors. (fn. 431) Thomas Taylor, vicar by 1550, (fn. 432) lived in Oxford (fn. 433) and in 1551, when he could neither repeat the Commandments nor prove the Articles, was also rector of North Cerney. (fn. 434) John Strange, who held other livings including Maiseyhampton, became vicar in 1559 but resigned the following year. (fn. 435) Nathaniel Harford, non-resident vicar from 1564, (fn. 436) also held Hatherop until c. 1572 (fn. 437) and then another living. (fn. 438) He had not preached for over a year in 1576 when he was apparently dispossessed. (fn. 439) His successor William Salwey, (fn. 440) a non-graduate, was another pluralist. (fn. 441) In 1585 Henry Dunne became vicar but following confusion over the patronage was made curate later that year. (fn. 442)

Edmund James, who held the living from 1586 until 1589 with Hatherop, (fn. 443) was described as a quarreller in 1593. (fn. 444) Christopher Nicholson, who succeeded him in 1617, (fn. 445) was described as a preacher in 1650. (fn. 446) The preservation of the church windows during the latter part of his incumbency was possibly due to his curate Robert Clark, whose opposition to dissenters is revealed in a tract written in 1660 following an attack on a Fairford meetingplace. (fn. 447) John Shipman, vicar from 1656, was licensed to preach in the church in 1673. Joseph Atwell, vicar 1738–68, employed curates to serve the living, which he held with Oddington from 1739. (fn. 448) In 1778 Edward Sparkes, a pluralist and formerly headmaster of the King's School, Gloucester, for 35 years, became vicar of Fairford (fn. 449) where he lived and had a curate. (fn. 450) He died in 1785 and his successor James Edwards (d. 1804), also a pluralist, (fn. 451) was resident. (fn. 452) John Mitchell, vicar from 1810, lived in Gloucester and appointed curates. (fn. 453) Francis William Rice, his successor from 1828, also employed curates but was usually resident until 1869 when he inherited the barony of Dynevor (Carms.). From then until his death in 1878 estate and parliamentary duties necessitated periods of absence. (fn. 454)

Some of the lights mentioned in the parish church in 1432 (fn. 455) were possibly supported by the guilds of the Virgin Mary and Holy Trinity recorded in the late 1480s and by the fraternity of St. Cross which may have been dissolved by the later date. (fn. 456) John Tame by will dated 1497 assigned £240 to found a chantry in Fairford church but he later used the money to buy land in Castle Eaton (Wilts.) for its endowment. After his death there was a dispute over the land (fn. 457) but the chantry had apparently been established by 1532. (fn. 458) The priest of a free chapel at Kinley in Nympsfield, where the elder Sir Edmund Tame had acquired the manor, was later said to serve it (fn. 459) but in 1547 was refusing the daily service that was required from him. (fn. 460) The second chaplain recorded in 1532 (fn. 461) served a chantry in the church founded by Sir Edmund and on which a Wiltshire manor, worth £7 in 1535, was conferred. (fn. 462) It was presumably the chantry dedicated to St. Edmund which had been despoiled by 1546. (fn. 463)

Elizabeth Farmor's educational bequest to the parish also provided for a salary of up to £40 for a minister, to be chosen by her uncle Samuel Barker and his heirs, preaching in the church on Sunday afternoons. (fn. 464) The sermons were given from 1739 by the vicar who received £40 from land in Chaceley (Worcs., later Glos.). (fn. 465) Later he apparently received a larger part of the income from the land but in 1817 the original provisions of the bequest were implemented. The Mercers' Company of London probably paid the salary from 1890 (fn. 466) but in 1977 there were no Sunday afternoon sermons. (fn. 467)

The churchwardens, who owned property in the town by 1487, (fn. 468) established the church or parish lands charity in 1564 to maintain the church, the highways, and an alms-house. The charity had an income of £2 4s. 10d. in 1601. (fn. 469) In 1648 the feoffees leased a house for 21 years to two glaziers, John Scriven of Burford and his son Edward, by the service of repairing the church masonry, leads, and windows, apart from the chancel, (fn. 470) and John was living there in 1662. (fn. 471) In 1729 a Fairford man contracted with the churchwardens to maintain the tower leads for 40 years, (fn. 472) and between 1774 and 1797 the churchwardens' expenses were met almost wholly by the charity. (fn. 473) In 1754 some property was granted under a long lease to James and Esther Lambe in return for an annuity but that lease was set aside following Chancery proceedings brought against the feoffees in 1857. A Scheme of 1859 appointed new trustees and divided the income equally between the church, the highways, and the poor. (fn. 474) The income for road repairs was spent irregularly, leading to an accumulation of funds, from which the cost of a church restoration was partly defrayed in 1891. (fn. 475) Under a Scheme of 1971 the income of the charity was divided equally between church repairs and the poor, and in 1976 £600 a year was derived from investments and one property. (fn. 476)

The church, dedicated to ST. MARY by 1432, (fn. 477) is built of ashlar and has a chancel with north vestry and north and south chapels, a central tower, and an aisled and clerestoried nave with south porch. Most of the fabric dates from a rebuilding in the late 15th century, at the expense of John Tame and completed by his son Edmund, (fn. 478) but the lower part of the tower and the eastern responds of its arcades survive from the 14th-century building, which was cruciform and had an aisled nave. The respond of the north arcade has a 13th-century base and shaft but the capital and arch date from the early 14th century. The south respond which is also of the early 14th century was presumably reconstructed at that time. At the late-15th-century rebuilding the tower was provided with octagonal angle turrets and a new top stage, some earlier ornaments being reset in the new work. The rest of the church was completely rebuilt in a uniform late-perpendicular style.

The work created large areas of windows which were filled with stained glass representing in the main windows scenes from the Old and New Testaments and in those of the clerestory figures important in the early life of the Church. The designer may have been Barnard Flower, the king's master glass painter. (fn. 479) The survival of the windows was celebrated in poetry by Richard Corbet (d. 1635) (fn. 480) and they later attracted the attention of antiquaries such as Anthony a Wood and Thomas Hearne. (fn. 481) In 1703 two of the western windows were damaged by a storm (fn. 482) and Elizabeth Farmor, by will proved 1706, left £200 for repairs and protective wire frames. (fn. 483) Because of Chancery proceedings the work had not been carried out by 1717 when it was assigned to a London wireworker and a Fairford glazier. (fn. 484) By the mid 19th century the windows had fallen into disrepair and a campaign to preserve them, which had been launched by 1868, (fn. 485) led to a considerable literature. (fn. 486) Queen Victoria headed the list of subscribers to their restoration during 1889 and 1890 (fn. 487) when a Birmingham firm provided a copy of that part of the great west window which had been lost during an attempt at restoration in the middle of the century. (fn. 488) During the Second World War the glass was removed for safe keeping. (fn. 489)

Original fittings which survive include the south door, the rood- and parclose-screens, 14 stalls in the chancel, and the font, the base of which was found in the vicarage garden c. 1920. (fn. 490) An altar dated 1626 was moved from the chancel to the south chapel in 1920. (fn. 491) Under a bequest by Andrew Barker the church was repewed in 1702, (fn. 492) but new seats were installed, probably during restoration work in 1852 when paintings within the tower arches were uncovered. (fn. 493)

The north chapel, which housed the chantry-chapel established under John Tame's will and was dedicated to Our Lady by 1534, (fn. 494) contains monuments to John Tame, his wife, and several descendants. (fn. 495) It was refitted by John Raymond Raymond-Barker before 1862. (fn. 496) During 1912 and 1913 William Lygon, Earl Beauchamp, whose putative ancestor Roger Lygon was lord of Fairford in the mid 16th century, provided a reredos designed by Geoffrey Webb. (fn. 497) John Tame's will dated 1497 included a bequest for a great fourth bell. (fn. 498) The peal, which included bells cast, some by the Rudhall family, in 1678, 1735, 1760, and 1783, numbered six in 1851 when one was replaced by C. & G. Mears of London. Two were added the following year (fn. 499) and the peal was recast by John Taylor of Loughborough (Leics.) in 1927. (fn. 500) The church has a mazer bowl of c. 1485 and the plate includes a chalice and paten made in 1576, possibly from earlier pieces, a flagon given by Andrew Barker's widow Elizabeth (d. 1704), and a paten of 1702 given by his daughter Mary. (fn. 501) The registers survive from 1617. (fn. 502) The churchyard has many tomb-chests, including that with rhyming epitaph of the mason Valentine Strong (d. 1662), (fn. 503) and a war memorial of 1919 designed by Ernest Gimson. (fn. 504)

Nonconformity

The meeting of Baptists recorded in 1653 at Netherton, probably Milton End, was possibly that whose meeting-place was attacked in 1660. (fn. 505) Six protestant nonconformists were recorded in Fairford in 1676 (fn. 506) and the Baptists, who were again recorded in 1685, (fn. 507) opened a new chapel south of Milton Street in 1724. (fn. 508) By 1743 membership of the meeting had risen to 60. (fn. 509) Thomas Davis was minister from 1744 until his death in 1784 (fn. 510) and the merchant and writer, Anthony Robinson (1762–1827), for a few years in the 1780s. (fn. 511) In the late 18th century, when the meeting included members of the Hooke, Thompson, and Wane families, who were important local tradesmen, (fn. 512) the chapel was rebuilt and it retains the gallery and panelling which has been reset. (fn. 513) The manse in East End was replaced after 1840 (fn. 514) by the house west of the chapel left by William Hooke (d. 1834). (fn. 515) In 1851 the chapel attracted congregations of up to 195. (fn. 516) In 1919 the Baptists united with the Congregationalists of the Croft chapel and services were held in the Milton Street chapel which from 1951, when the union was dissolved, was used with the manse by the Congregationalists alone. (fn. 517) The house was sold in the mid 1960s when the chapel closed for a time. In 1977 the meeting had 13 members. (fn. 518)

In 1731 the manor-house was licensed as a meeting-house. (fn. 519) Most of the 10 Presbyterians meeting there in 1735 were members of James Lambe's family (fn. 520) but by the early 1770s the meeting had evidently united with the Croft chapel. (fn. 521) The membership of a meeting of Independents in Fairford rose from 10 in 1735 to 30 by 1743, (fn. 522) and the following year a chapel was built north of the Crofts. (fn. 523) A manse was built east of the old Gloucester road in the early 19th century (fn. 524) and the chapel was enlarged in 1817. (fn. 525) In 1820 the minister was described as Congregational. (fn. 526) The chapel, minister who espoused the tenets of the Particular Baptists, withdrew, apparently in the early 1830s, to form a separate church. (fn. 527) The Croft chapel, which had an average attendance of 60 in 1851, (fn. 528) was rebuilt with a schoolroom and vestry in 1862 when it was described as Congregational. (fn. 529) The chapel, which after the union with the Baptists was used for various secular purposes, was demolished in the mid 1960s. (fn. 530)

The Independents and Baptists who registered a house in the parish in 1834 probably followed the Particular Baptist minister in withdrawing from the Croft chapel. (fn. 531) Ebenezer chapel, which the Particular Baptists had built west of Coronation Street by 1862, (fn. 532) could seat 100 in 1889. (fn. 533) It closed before 1919 (fn. 534) and had been converted as a doctors' surgery by 1953. (fn. 535)

Quakers, one of whom was presented in 1685, built a meeting-place in 1740 (fn. 536) but no other evidence of the meeting has been found. Primitive Methodists, who were possibly meeting in Fairford by 1862, (fn. 537) opened a chapel in converted cottages in Milton Place, west of Coronation Street, in 1867. (fn. 538) The chapel, which closed c. 1925, (fn. 539) was used by a boy scout troop in 1957 (fn. 540) but was disused in 1977. Other houses were registered for nonconformist use in 1820, in 1841 by John William Peters, formerly rector of Quenington, and in 1851. (fn. 541) There was a small group of Roman Catholics at Fairford in the early 18th century. (fn. 542)

Education

There was an unlicensed teacher in Fairford in 1619. (fn. 543) By 1705 a Mr. Smith of London had given a rent-charge of 30s. in Fairford for teaching poor children to read (fn. 544) and a schoolmaster was recorded in 1715. (fn. 545) The rent-charge has not been traced after 1791 (fn. 546) and no evidence has been found of the application of a gift of £1 by a Mrs. Morgan for teaching 4 poor girls. (fn. 547)

The Fairford free school (fn. 548) was founded by Elizabeth Farmor's will, proved 1706, by which she left £1,000 to provide a salary of £10 for a schoolmaster teaching 20 poor children of Fairford; (fn. 549) the bequest was used, following Chancery proceedings, (fn. 550) to buy land in Chaceley in 1718. (fn. 551) The previous year it had been decreed in Chancery that a legacy of £500, left by Mary Barker (d. 1710) for teaching 40 poor children and for religious books, was to benefit Fairford and in 1721 that bequest was used to buy land. (fn. 552) A Chancery decree of 1738 combined the bequests and 60 boys aged between 5 and 12 received free education in the school which was built later that year in High Street on land bought with the proceeds of another of Elizabeth's charitable bequests. Part of the latter had been used with charity money for Cricklade (Wilts.) in 1722 to buy land from which half of the rents were assigned to the Fairford schoolmaster. The master, nominated by the lord of the manor, had an assistant or usher who received £10 a year from the endowments (fn. 553) which the master administered in the mid 18th century. (fn. 554) Elizabeth Farmor's educational bequest also provided for Sunday afternoon sermons in Fairford church and support for widows in Lady Mico's alms-houses in Stepney (Mdx.) but the latter provision was not implemented until 1817. The Mercers' Company of London, which administered the alms-houses, had apparently acquired the Chaceley land by 1890 when it probably became responsible for the payments to the school and preacher. It redeemed the schoolmaster's part on selling the land in 1920. (fn. 555)

In 1817, when the curate Thomas Richards was master, the school, which had been enlarged by John Raymond-Barker, became a National school for the children of the town and neighbourhood. Education for 60 boys and 60 girls from the parish was free and the other children paid pence or fees. The Chancery decree of 1817, which authorized spending up to £30 a year on the girls' school, provided for a salary of at least £60 for the master, (fn. 556) who taught 101 boys in 1818 when a mistress received £25 for teaching 129 girls. The endowments, to which more land had apparently been added, produced £106 5s. (fn. 557) In 1847 the income was made up of £36 2s. from pence and £112 2s. from the endowments (fn. 558) which were augmented in 1877 when a Scheme united Lady Mico's apprenticing charity with the school. (fn. 559) In 1866 Thomas Morton, the curate, taught in place of the master who was dismissed for neglect, (fn. 560) and the school, enlarged in 1873, (fn. 561) had an average attendance of 173 in 1889. (fn. 562) Called Farmor's Endowed school in 1904, (fn. 563) it did not become fully co-educational until 1922 (fn. 564) and in 1927 131 of the 188 children were aged over ten, many coming from outside the town. (fn. 565) New classrooms were opened east of the infant school in London Road in 1955 when both schools were reorganized as a primary school. The building in High Street closed in 1961 and more classrooms were built in London Road between 1966 and 1973. In 1977 Fairford C. of E. Primary school drew 328 children from the town, Horcott, and Fairford R.A.F. base. (fn. 566) The Farmor's Endowed Schools Foundation, established under the Scheme of 1877, (fn. 567) sold its last remaining land in 1970. In 1976 it had an income from investments of c. £1,400 which was used, under a Scheme of 1973, to provide educational grants for three persons aged under 25 and to cover expenses of the primary and comprehensive schools not met by the county council. (fn. 568)

An infant school, begun in 1831, taught 44 children in 1833 when it was supported by fees and subscriptions; (fn. 569) it was possibly that recorded in 1838. (fn. 570) Fairford C. of E. Infant school, established in 1866, was held in a converted barn and had an average attendance of 72 in 1869 when it was supported by voluntary contributions and pence. (fn. 571) In 1873 a new building was opened in London Road. (fn. 572) The average attendance, which in 1889 was 65, had risen, after enlargement of the building, to 85 by 1897 (fn. 573) but fell from 75 in 1910 to 29 by 1936. (fn. 574) In 1955 the school became part of the primary school.

A fee-paying boarding and day-school with 67 children in 1833 (fn. 575) was probably held in Mount Pleasant House, the site of a private school by 1814 and until at least 1863. (fn. 576) A private school for girls in High Street, established by 1842, (fn. 577) was later held in a cottage north of Mount Pleasant House until at least 1876. (fn. 578)

A Sunday school was supported by charity money from the early 1680s. (fn. 579) The church Sunday school, to which John Carter (d. 1811) left £50 stock, (fn. 580) was evidently that attached to the free school which taught 209 children in 1833, (fn. 581) and in 1976 £169 was paid for the use of the Sunday school by his charity. (fn. 582) The Croft chapel ran a day-school by 1856 (fn. 583) but it did not have a schoolroom until 1862 (fn. 584) and has not been traced after 1863. (fn. 585)

In 1891 the county council made a grant to a school of science and art in Fairford but no other record of the school has been found. (fn. 586) Farmor's School, a secondary modern school, opened in 1962 in a new building on the site of Fairford Park. (fn. 587) In 1966 it became a comprehensive school (fn. 588) and had 660 children from the south-eastern part of the county on the roll in 1977. (fn. 589)

Charities for the Poor

The church or parish lands charity established in 1564 maintained an alms-house which had six occupants in 1662, when it stood north of Park Street. (fn. 590) It had been burnt down by c. 1708. (fn. 591) The third of the charity's income designated for the poor by the Scheme of 1859 included a subscription of £2 2s. to Gloucester Infirmary or a similar institution for the treatment of patients; (fn. 592) it was paid to the infirmary between 1861 and 1868 and to the cottage hospital from 1877. The rest was spent on coal and clothing (fn. 593) and in 1970 the charity helped c. 30 people. (fn. 594) That half of the income which from 1971 went to the poor was used in 1976 to provide television sets for the cottage hospital. (fn. 595)

Thomas Morgan by will dated 1632 left £100 for the poor. Though £20 lent out c. 1663 was lost, another part, used with a charitable gift of £5 from Morgan Emmot to buy land for Lady Mico's apprenticing charity (fn. 596) in 1673, had been repaid by 1688. (fn. 597) The funds of the charity, standing at £100, were lent out but in 1757 £30 was spent on the purchase of the pest-house and from that time the overseers distributed £1 10s. a year to the poor. About 1787 the rest of the principal was spent on building Tinkers Row and from then until 1836 the overseers distributed £5 a year to the poor on Good Friday. (fn. 598)

By deed of 1670 Andrew Barker gave Jane Mico, Lady Mico, his sister-in-law, a rent-charge of £5 4s. for a weekly distribution of bread to the poor of Fairford; the charity became known as Lady Mico's bread charity. (fn. 599) William Butcher by will proved 1715 gave £40 for a weekly bread charity, and from 1757, when it was put towards buying the pesthouse, bread worth £2 was provided from the poorrate. (fn. 600) By 1829 the two charities were distributed together every third week (fn. 601) and in 1836 33 people received bread. (fn. 602) The vicar Frampton Huntingdon (d. 1738) left £10 for a bread charity for 20 poor church-goers. (fn. 603) The principal, which was lent to a baker until 1786, was then spent on building Tinkers Row and the overseers distributed 10s. a year in bread on 21 August. (fn. 604) Robert Jenner by will dated 1770 left £10 for a distribution to 5 poor widows on Christmas Eve and Alexander Colston (formerly Ready) (d. 1775) left £105 for a distribution to 4 poor widows at Candlemas. Both charities were spent on building Tinkers Row (fn. 605) and the overseers distributed 10s. and £5 5s. in cash respectively. (fn. 606) Payment for the Jenner charity had stopped by 1829 (fn. 607) but was resumed following the transfer of Tinkers Row and the pest-house to the churchwardens, who managed the property also for the Morgan, Butcher, Huntingdon, and Colston charities. By the 1850s the churchwardens distributed £5 5s. a year for the Jenner and Colston charities combined. (fn. 608)

John Carter (d. 1811) left £300 stock for a distribution to the poor in December (fn. 609) and a bequest by Sarah Luckman (d. 1830) for a distribution of cash in February realized £98 by 1836. (fn. 610) All the above-mentioned charities, except for the church or parish lands charity, were amalgamated in 1869. (fn. 611) John Harvey Ollney by will proved 1836 left £200 to Fairford for a Christmas coal and blanket charity, which was distributed from 1840 (fn. 612) and added to the combined charities in 1972. (fn. 613) In 1976 the income of the combined charities, c. £200, was distributed in vouchers. (fn. 614)

A trust fund of £20 established under the will of Elizabeth Cull (d. 1674) had not been claimed by 1681 when it became payable to the poor. Under the will of her trustee, William Oldisworth (d. 1680), it was used to buy 26s. of bread a year for four poor boys attending a Sunday school, the teacher of which received 4s. William's heir James Oldisworth (d. 1722) also paid 40s. interest on the original grant, evidently believing it separate, but from c. 1725 his daughter Muriel Loggan only paid for the bread and the teacher. (fn. 615) The charity had been lost by 1829. (fn. 616)

Lady Mico by will proved 1671 left £400 for apprenticing four poor boys of the town each year. In 1673 the principal was used with other charity money to buy land, out of the rents of which the borrowed money had been repaid by 1688. (fn. 617) From the later 18th century, although boys were sometimes apprenticed as far afield as Gloucester, Kidderminster, Banbury, and London, the difficulty of finding suitable masters led to an accumulation of funds; £120 was lent between 1798 and 1806 to the workhouse and £200 had been invested in stock by 1829. By then to prevent masters from breaking agreements part of the premium was paid at the end of the period of apprenticeship. (fn. 618) The charity had over £1,114 stock in 1871 when a Scheme authorized spending £630, from funds and sale of stock, on building the infant school and enlarging the free school, with which the charity was united for educational purposes in 1877. (fn. 619)