Pages 122-174

A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

In this section

DYMOCK

DYMOCK is a large rural parish straddling the river Leadon midway between the market towns of Newent and Ledbury (Herefs.) and 18 km northwest of Gloucester. Its village, standing in an area of Romano-British roadside settlement, was in the late Anglo-Saxon period the centre of a large royal estate, much of it in the hands of a tenantry that included numerous peasant farmers. The village remained primarily an agricultural settlement and in the medieval period the parish was largely populated in scattered farmsteads. One of several small hamlets formed later grew into the village of Bromesberrow Heath in the 19th and 20th centuries. Although the farmers were involved in parish life, after the 16th century Dymock was dominated by the owners of its several estates with the Lygons of Madresfield (Worcs.) being particularly prominent in the half century before the First World War. In the 20th century orcharding, long the main business of many farms, declined but agriculture continued at the heart of Dymock's economy. In the later 20th century the main settlements grew as they became residential areas for retired people and people working elsewhere.

BOUNDARIES AND DIVISIONS

The ancient parish covered 7,009 a. (2,836 ha). (fn. 1) Two thirds of it lay west of the Leadon, which after being augmented by the waters of the Preston and Kempley brooks turns eastwards from its southwards course and at Ketford follows the channel of a former mill leat flowing north of its original twisting course. (fn. 2) The parish extended northwards into the Leadington, to the west of the Leadon, and eastwards to Cut Mill and Lintridge, to the north of the river. Its boundaries, which on the east and on parts of the north and west were those of the county, (fn. 3) mostly followed natural and ancient features, including the Ludstock brook, a tributary of the Preston brook, west of the Leadington. (fn. 4) East of the Leadon the northern boundary closely followed a road that further east once formed the main route linking Ledbury with Gloucester. (fn. 5) The long southern boundary followed a road but in the east took a series of irregular turns (field boundaries) to include a substantial mound known as Castle Tump. Further west it passed a tree called Gospel Oak standing where Dymock met Newent and Oxenhall. (fn. 6) The tree, presumably a place where Bible readings were given on parish perambulations, died some time before its remains were blown down in 1893. (fn. 7) The slightly more irregular western boundary followed a short section of the Kempley brook and further north passed a tree called the Stonehouse Oak in 1796. (fn. 8) In 1935 the parish of Preston, 897 a. to the north-west, was added to Dymock (fn. 9) and in 1992 the village of Bromesberrow Heath in the north-east was transferred to Bromesberrow, the revised boundary following the M50 motorway, and Cut Mill in the east to Redmarley D'Abitot (Glos., formerly Worcs.). (fn. 10) The following account deals with the parish as it was constituted before 1935.

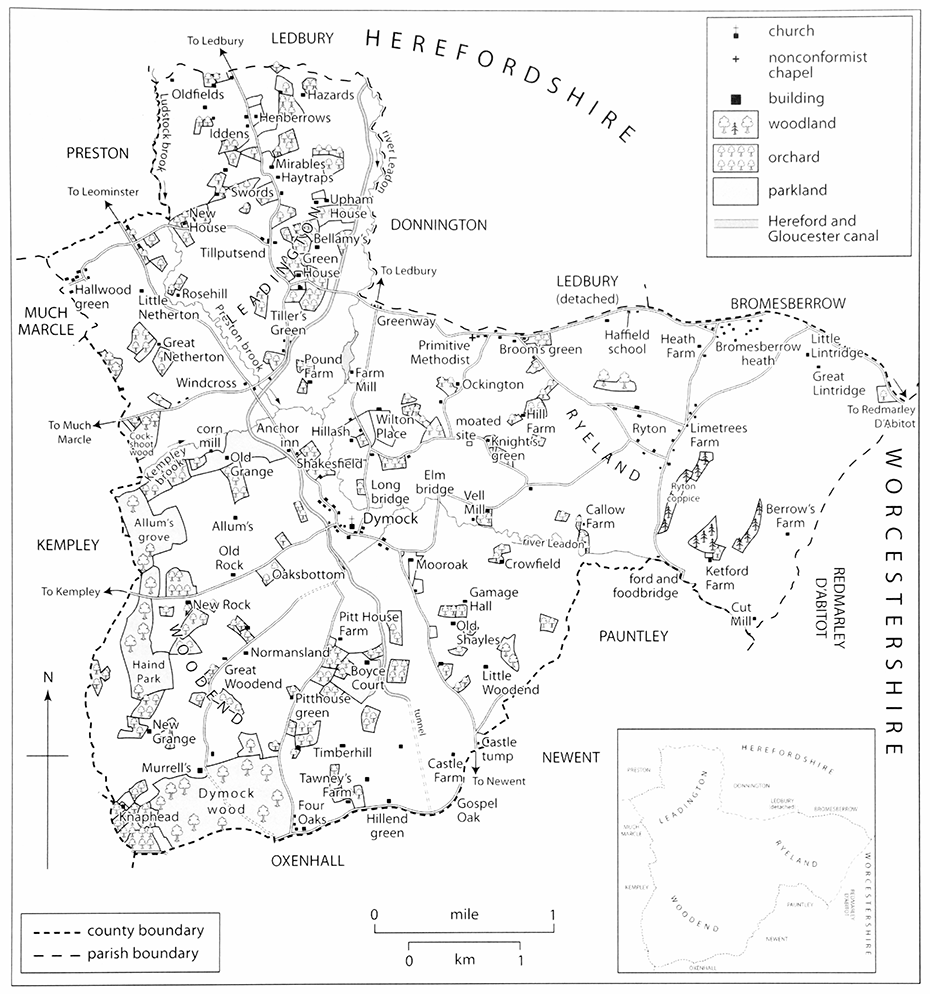

Map 8. Dymock 1880

Dymock, on the eve of the Conquest a royal manor, later contained five tithings with Flaxley in the south-west and Woodend (also known as Gamage Hall) in the south being based on manors created by grants in the 12th century. Leadington was in the north-west, and the land east of the Leadon was divided between Ockington and, to its east, Ryton (sometimes called Ryeland). (fn. 11) By later medieval times the parish also had three divisions or hamlets: Woodend, Leadington, and Ryeland. (fn. 12) The units of civil government in the parish, (fn. 13) they came to a single point in the parish churchyard. (fn. 14) Woodend, which was made up of Gamage Hall and Flaxley tithings, included all of the parish south of the Kempley brook and the river Leadon apart from a bit north of Dymock village street. Leadington, based on the tithing of the same name, extended from the street to take in the area north of the Kempley brook. Ryeland, comprising Ockington and Ryton tithings, covered the area east of the Leadon. (fn. 15)

LANDSCAPE

The Leadon flows through Dymock in a valley at c.30 m. Most of the parish is gently rolling countryside rising to over 60 m in places and reaching 90 m at Gospel Oak on the south boundary, but there is flatter land beside the Preston and Kempley brooks in the north-west and west and steep hills hem in the Leadon near Ketford in the east. The land is drained by small tributary streams, of which the Preston and Kempley brooks meet before flowing into the Leadon north-west of Dymock village near Windcross. The stream flowing north of the village was called Jordan's in the mid 16th century. (fn. 16) Land by the river and its principal tributaries is alluvial. Elsewhere it is mostly formed of sandstone (fn. 17) and the lighter soil on the higher land in the east, part of 'the ryelands', (fn. 18) is especially prone to erosion.

Early dispersed settlement and the abundance of ancient closes point to the emergence of much of the parish from ancient woodland. A wood measuring three leagues by one league was recorded in Dymock in the late 11th century (fn. 19) and the south-western part of the parish once belonged to a great wood called Teds (Tetills) wood that extended across the county boundary. (fn. 20) In the 1840s, when the parish had 457 a. of woodland or plantation, Dymock wood, on the south-western boundary, covered 171 a. and Haind (Hen) Park (75 a.), Allum's (70 a.), and Cockshoot (22 a.) woods formed a wide and almost continuous band of woodland on the west side. (fn. 21) Of those three woods, part of an estate of Flaxley abbey in the Middle Ages, (fn. 22) Haind Park was presumably the park or hay recorded in the 13th century. (fn. 23) The park of Chesterford recorded in 1394 was elsewhere in the parish. (fn. 24) Beginning in the later 19th century a new wood was planted in the east on the hillsides above Ketford, (fn. 25) but the total area of woods and plantations, 326 a. in 1905, (fn. 26) was reduced by the felling of Cockshoot wood in the early 1920s. (fn. 27)

Open fields and common meadows, existing in all parts of the parish save the south-west, were inclosed at an early date (fn. 28) and the former commons of the parish were represented at the time of the Commons Registration Act of 1965 primarily by two small pieces of Hallwood green in the north-west corner on the boundary with Much Marcle (Herefs.). (fn. 29) Orchards, already numerous in the mid 16th century, (fn. 30) were a major feature of the landscape in the later 18th century. (fn. 31) In the 18th and 19th centuries several landowners created small parks next to their houses, one of the first being at Boyce Court in the south of the parish. (fn. 32) The park at the Old Grange, in the west, was made a golf course in the 1990s. (fn. 33)

COMMUNICATIONS

Roads and Bridges

The highway from Newent that entered Dymock beside Castle Tump in the late 13th century (fn. 34) was part of a way from Gloucester into Herefordshire. After passing Portway Top, (fn. 35) presumably on the rise once known as port hill, (fn. 36) it turns west along the village street which also marks closely the line of a Roman route coming from the east, probably from Tewkesbury, and continuing towards Stretton Grandison (Herefs.). (fn. 37) Beyond the village, where Stoneberrow (Stanborough) bridge carried it over Jordan's brook in the late 16th century, (fn. 38) the medieval road continued to Windcross from where it ran north-westwards to Hallwood green, passing by Great and Little Netherton. (fn. 39)

A number of other roads or lanes linked the village with nearby towns in the early 18th century. Counters Lane, the way northwards to Ledbury, (fn. 40) dipped from the eastern end of the village street into the Leadon valley, where it followed a causeway known as Long bridge, and continued northwards up to the Lynch and on past Hillash to Greenway. Earlier occupants of Hillash had made bequests for the causeway's maintenance. (fn. 41) Ways to Ross-on-Wye (Herefs.) and Mitcheldean followed lanes leading westwards and southwards to Kempley and Four Oaks respectively. (fn. 42) The parish had other lanes and also an extensive network of footpaths that, together with the footbridges on them, the Dymock manor court sought to maintain in the 18th century; many of the paths linked outlying farmsteads to the village and several were called church ways. (fn. 43) The path known as Yokeford's Way in the 16th century branched off the Four Oaks lane near Oaksbottom towards Normansland and Dymock wood. (fn. 44) In the south-west, where a woodland path was known as 'Staurnchesway' in the mid 13th century, (fn. 45) a lane running south-westwards through Haind Park wood to Kempley green was closed in 1819. (fn. 46)

The road from Newent to Ledbury by way of Dymock village was turnpiked in 1768 (fn. 47) and was the responsibility of the Newent turnpike trust from 1824. (fn. 48) Tollgates were placed at the east end of the village, including one across the entrance to the main street, and at crossroads at Greenway. (fn. 49) About 1835, on the construction of a new road beyond Windcross to Preston, the village street became part of a route linking Newent and Leominster (Herefs.) (fn. 50) and the road past Little Netherton was abandoned (fn. 51) The new road was a turnpike until 1871. The Newent–Ledbury road remained a turnpike until 1874. (fn. 52)

Long bridge, from which timbers were stolen in 1754, (fn. 53) was improved in 1789 and 1790, when brick culverts were constructed under the causeway. (fn. 54) The county repaired the main span, as well as a small bridge carrying the Newent road over a stream east of the village, in 1847. (fn. 55) Elm bridge downstream on the Ryton road, leading off the Newent road, provided an alternative crossing of the Leadon but in 1790 the road running north-westwards from the bridge towards the Lynch was closed. (fn. 56) The bridge was rebuilt in 1901 (fn. 57) and the junction of the Newent and Ryton roads was widened by removing the parish pound in 1921. (fn. 58) Another way from Newent to Ledbury crossed the Leadon into Dymock downstream at Ketford and ran northwards through Ryton. (fn. 59)

The road crossing the Dymock–Ledbury road at Greenway is part of a route that led westwards across Bromesberrow heath from the Gloucester–Ledbury road. Its crossing of the Leadon, not far from Roman occupation in Donnington (Herefs.), (fn. 60) was known in the late 18th century as Chester's bridge (fn. 61) and is presumably the place called Chester ford in 1394. (fn. 62) West of the river the road forks, one branch leading northwards through the Leadington towards Ledbury and the other leading southwards and then westwards by way of Tiller's green, Windcross, and Kempley to a junction in Much Marcle with the road from Ledbury to Ross-on-Wye. The road to Much Marcle was a turnpike between 1833 and 1871 (fn. 63) and tollgates were sited at the west end of Bromesberrow heath and at Windcross. (fn. 64)

The M50 motorway, opened in 1960, (fn. 65) crosses the parish from the north-east at a point near Bromesberrow Heath to the south at Four Oaks. Of the lanes it severed that at Four Oaks from the village was diverted to a junction with the lane in Dymock wood.

Canal and Railway

The Hereford and Gloucester canal opened across the centre of Dymock in 1798 following the construction of the Oxenhall tunnel. (fn. 66) It emerged from the tunnel in a deep cutting near Boyce Court and its northwards course passed immediately west of Dymock village before curving by the Old Grange and Tiller's green to adopt a route close to the river Leadon. (fn. 67) A tramroad following the line of the lane between the village and Four Oaks in 1807 was possibly laid to carry materials for the canal's construction. No later record of it has been found. (fn. 68) In 1881 the canal was closed between Gloucester and Ledbury to make way for a railway. The line, which opened in 1885, carried passenger traffic until 1959 and closed in 1964. (fn. 69) It took a more westerly route than the canal to enter Dymock at Four Oaks and north of the village it followed a direct route east of Tiller's green to follow the canal's course alongside the Leadon. There was a station next to the village (fn. 70) and, from 1937, a halt by the road west of Greenway. (fn. 71)

Among the remains of the canal, the section in the cutting north of the Oxenhall tunnel has been dammed to form a stretch of water, which in 2002 was overgrown and silted up towards the tunnel entrance.

POPULATION

Sixty-eight tenants, including a priest, lived on Dymock manor in 1066 (fn. 72) and sixty-three parishioners were assessed for tax in 1327. (fn. 73) A muster roll of 1542 named 108 men of the parish, (fn. 74) which was said to have c.440 communicants in 1551, (fn. 75) 106 households in 1563, (fn. 76) 400 communicants in 1603, (fn. 77) and 140 families in 1650. (fn. 78) About 1710 the population was estimated at 1,000 living in 250 houses. (fn. 79) About 1775 it was estimated at 1,116 (fn. 80) and in 1801 it was 1,223. Despite a small drop in the 1840s, the population grew to 1,870 in 1861, after which it fell to 1,149 in 1931. The addition of Preston in 1935 brought only a small increase and Dymock's population, having risen to 1,283 in 1991, was reduced by the loss of the Bromesberrow Heath area in 1992. In 2001 it was 1,141. (fn. 81)

SETTLEMENT

Archaeological investigations reveal that RomanoBritish settlement took place along the ancient road to Stretton Grandison on ground rising above the river Leadon to the north. Part of that settlement lies under the present village of Dymock (fn. 82) and in the 1770s ancient foundations and causeways were reported in fields 'above a quarter of a mile from the church'. (fn. 83) Although the village was the focus of substantial settlement in the late Anglo-Saxon period, the pattern of medieval settlement was largely one of scattered farmsteads. They dotted the surrounding countryside in the 14th century, some houses standing on earth platforms or in or next to moated enclosures. Many farmsteads were later abandoned (fn. 84) while the filling of encroachments on roadside wastes and common land with clusters of cottages from the 17th century led to the formation of several small hamlets. (fn. 85) Building in the 19th and 20th centuries latterly included new houses and bungalows beside several of the remaining farmsteads and many more dwellings in Dymock village and in the newer village of Bromesberrow Heath.

DYMOCK VILLAGE

The village has one main street along the road from Newent to Leominster. The size of its church, at the eastern end, indicates the presence of a large congregation in the late Anglo-Saxon period and the early Middle Ages. Burgage holdings created probably after the justiciar Hubert de Burgh ordered the sheriff to hold a market and a fair on the royal manor in 1222 (fn. 86) were not developed to form a market town but several properties in the village street, including copyhold cottages and a close west of the churchyard, continued to be described as burgages in the 17th and 18th centuries. (fn. 87)

The church, standing west of the Newent–Ledbury road, is set back from the street behind a green. The green, known in 1791 as Wintour's green, (fn. 88) was enlarged in the late 19th century following the demolition of the vicarage house on its west side. (fn. 89) A church house (later the parish workhouse) stood at the south-eastern corner of the churchyard (fn. 90) and until the 1920s there was an old building near by known, like one once occupied by a chantry priest, as the Priest's House. (fn. 91) Of the buildings on the east side of the green the Beauchamp Arms, facing the street next to the entrance to the Ledbury road, was formerly known as the Plough. (fn. 92) The White House, across the street from the green, is a former farmhouse on the rectory estate. (fn. 93) It stands in the place of a house that was the birthplace of John Kyrle (1637–1724), the 'Man of Ross', (fn. 94) and the home of the Winter family in the later 17th and early 18th century. (fn. 95) High House, west of the churchyard, is a tall, mid 18th-century house that was remodelled in 1878 as the vicarage house by the 6th Earl Beauchamp, (fn. 96) who shortly afterwards demolished the old vicarage, incorporating part of its site in the garden of High House and adding the rest to the green. (fn. 97) The parish pound against the churchyard wall was removed about the same time. (fn. 98) The churchyard, which included the sexton's dwelling in the mid 19th century, (fn. 99) was approached from the west by a walk replanted with lime trees in 1874 (fn. 100) and was enlarged to the north in 1911. (fn. 101)

The village straggles along the street and its oldest houses are on the north side towards the west end. Two date possibly from the 15th century, another probably from the 16th century. (fn. 102) New building in the early 19th century, after the construction of the canal near by, included Great Wadley and the former George inn together on the site south of the street of a meeting place called Society Lodge. (fn. 103) To the east the former Ann Cam's school was built in the mid 1820s in place of an earlier school. (fn. 104) In the early 1840s the new Stoneberrow Place, in the centre of the village, was among a group of cottages close to the canal (fn. 105) and a tollhouse stood in the road at the east end of the street. (fn. 106)

In the early 1880s a railway station was built off the street next to the abandoned canal. (fn. 107) A police station (closed in 1971) was erected opposite it on the Kempley lane in 1898 (fn. 108) but little other new building took place in the village before the mid 20th century. (fn. 109) Newent Rural District Council built a pair of houses in the street in 1948 and four pairs on the Kempley lane between 1949 and 1952. (fn. 110) In 1953 a new parsonage was erected north-west of High House. (fn. 111) The latter, which the RDC acquired, was converted as flats in 1957 (fn. 112) and two new bungalows were built in its grounds in 1963. (fn. 113) The village's growth away from the main street continued after the railway's closure in 1964, the site of the station being filled with an old people's home and several houses (fn. 114) and a housing estate being built off the Kempley lane. (fn. 115) Among new developments by the street were a council estate of 21 dwellings on the south side completed in 1966 (fn. 116) and a small estate of detached houses on the north side finished in 2001. (fn. 117)

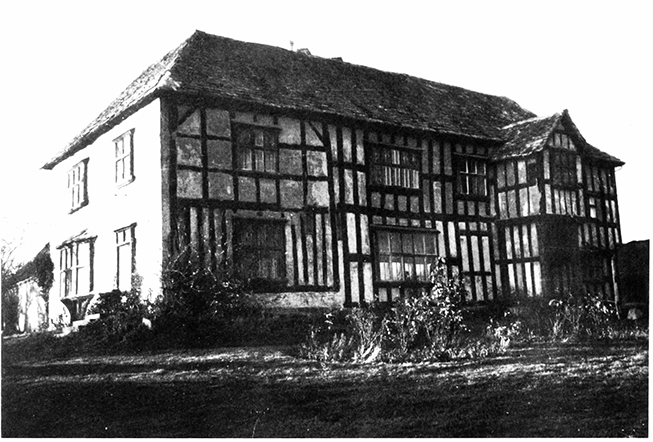

31. The Old Cottage, Dymock, in 1948

New building also took place on the fringes of the village next to long-established dwellings. It began in the mid 1930s when the RDC built five pairs of houses, two north of Long bridge on the Ledbury road, one to the east on the Newent road, and two further east at Batchfields on the Ryton road. (fn. 118) A schoolmaster's house was erected on the Ryton road in 1935 (fn. 119) and another pair of council houses was placed there during the Second World War. (fn. 120) Later private building contributed to the spread of the village. Some of the new houses were to the northwest at Shakesfield where in the 17th century several cottages had stood in the area of Maypole Farm, a farmstead north of a way then known as Butcher's Lane. (fn. 121) Others were to the south, on the line of the former railway, towards Oaksbottom, where in 1811 a new cottage and limekiln had stood. (fn. 122)

OUTLYING SETTLEMENT

Woodend

Boyce Court, south of Dymock village, is of medieval origin and for a time from the later 17th century was the seat of the lords of Dymock manor. (fn. 123) Further south the homestead at Timberhill was the centre of the largest farm on the Boyce Court estate in the mid 19th century. (fn. 124) Of the smaller farmsteads in the area Farr's, part of Little Dymock manor, was presumably inhabited by the de la Lynde family in the mid 13th century for it was known also as Lynde House or Place in the mid 16th. (fn. 125) Moor's Farm in the late 17th century was part of a holding called Hulker's and Bulker's. (fn. 126) Tawney's, close to the south boundary, is named after a local family in the mid 16th century (fn. 127) and contains a small 17th-century house.

On the eastern outskirts of the village a small farmstead at Mooroak, east of the Newent road, was occupied by the Loveridge family in the early 17th century. (fn. 128) In the 20th century several new houses were built to the north, including the council houses at Batchfields mentioned above. In 1962 the county council erected a small farmhouse to the north-east on the lane to Crowfield, (fn. 129) where a homestead is recorded from the mid 17th century. (fn. 130) Further south Gamage Hall is a farmstead on the site of the medieval manor of Little Dymock. (fn. 131) Two farmsteads near by were among copyholds of that manor, (fn. 132) which included a farmstead called 'Crekwardens' in 1515, (fn. 133) and both have been associated by name with the Shayle family. (fn. 134) The house at Old Shayles, so called in 1577, (fn. 135) was replaced in 1909. (fn. 136) Little Woodend, previously known as the Woodend or Shayles, (fn. 137) was the home of Edward Shayle in the early 16th century (fn. 138) and part of the Ricardos' estate in the early 19th. (fn. 139) In the mid 18th century the land farmed from Old Shayles took in the site of a tenement called Chancellors. (fn. 140) Mere Hills Farm, to the east in Welsh House Lane, was established by the county council on land bought in 1919; its house is dated 1921. (fn. 141) In the later 19th century a farmhouse to the west on the Newent road at Beaconshill (formerly Bickenshill) (fn. 142) was rebuilt as a small private house. (fn. 143) A lodge to Boyce Court stands on the opposite side of the road. (fn. 144)

In the west of the parish the Old Grange, so called in 1555, (fn. 145) stands on the site of a grange of Flaxley abbey and until the early 20th century was the centre of a large estate. (fn. 146) The farmstead to the south at Allum's, recorded from 1539, (fn. 147) passed into the estate in the late 17th century. (fn. 148) Further south there are two old farmsteads and a few other, mostly later 20thcentury, dwellings on the Kempley lane. Of the farmsteads the Old Rock, known as the Rock in 1509, (fn. 149) belonged to the Hill family until the early 20th century. (fn. 150) The New Rock, further west, was so called in 1657 (fn. 151) and has a 17th-century house. Clutterbucks, a copyhold tenement on the Old Grange estate (fn. 152) that was destroyed by fire in the 18th century, probably stood to the south-west close to the parish boundary behind Haind Park wood. (fn. 153) There was a keeper's cottage up against the wood until after the First World War. (fn. 154)

Of the farmsteads established in the south-west of the parish that known in 1543 as the New Grange stands on Flaxley abbey's former (Old Grange) estate. (fn. 155) Blacklands and Normansland, on opposite sides of the way to Dymock wood, were copyholds of the estate. (fn. 156) Blacklands has an early house encased in brick (fn. 157) and a timber-framed outbuilding that until 1922 stood near the parish church. (fn. 158) Normansland, so called in 1612, (fn. 159) was known earlier as Yokeford. (fn. 160) It was inherited in 1808 by Joseph Thackwell, (fn. 161) who added the farmstead at Great Woodend, further along the lane, to his estate in 1832. (fn. 162) Among the few houses built on or near the way to the wood in the 20th century were a pair of farm cottages near Normansland (fn. 163) and a house of 1925 east of the New Grange. (fn. 164) Walnut Tree Farm, on the edge of the wood, was occupied in the early 18th century by Thomas Murrell (fn. 165) and was later known as Murrell's or Upper Murrell's. Murrell's Cottage, a small 17th-century house a little to the north, was one of two adjacent cottages in the mid 19th century. (fn. 166) The farmstead at Knaphead, on the side of the valley west of the wood, was inhabited in 1684. (fn. 167)

Pitt House Farm, by the lane to Four Oaks, may be the place inhabited by men surnamed of or at the pit in the 14th century. (fn. 168) Occupied by the Wills family in the mid 16th century, the house was known variously in the mid 18th century as the Pitt House and Edulus Place. (fn. 169) Several houses and cottages once stood further south on the lane at Pitt House green, (fn. 170) one on the west side being called the Heath House in 1680. (fn. 171) A house called Sherlocks that had been pulled down by the early 18th century was near by. (fn. 172) The house at Farmer's, east of the lane, was empty in 1956 and was later demolished. (fn. 173)

The position of the mound at Castle Tump right on the parish's south boundary points to its antiquity and makes it an unlikely candidate for the site of the medieval manor of Dymock. In the later 13th century, when it was known as the castle of Dymock, the site inhabited by men surnamed of the castle may have been off the mound. (fn. 174) At Castle Farm, to the south-west, the timber-framed house standing within a moat was rebuilt and parts of the surrounding ditch were filled in following a fire in the 19th century. (fn. 175) In the mid 20th century a house was built on the drive to the house. (fn. 176) A small group of cottages beside the mound, the oldest of which dates from the 17th century, originated in settlement of waste land by the Newent road. (fn. 177)

Cottages were also erected to the west along the road marking the boundary with Oxenhall. A handful of early cottages stood on the western part of Hillend green, (fn. 178) where encroachment had begun by the mid 18th century. (fn. 179) Two pairs of identical cottages were built there in the early 20th century and the RDC erected two pairs of timber houses further east in 1947. (fn. 180) Among other new houses is a late 20thcentury farmhouse set back from the road. Further west at Four Oaks, where two men were building on encroachments in 1753, (fn. 181) cottages followed the lane northwards into Dymock. (fn. 182) The hamlet, which includes 20th-century council houses within Oxenhall, (fn. 183) has remained small.

Ryeland

The farmhouse at the Lynch, on the Ledbury road north of Dymock village, was a public house in the mid 19th century. (fn. 184) A cottage to the east at Little Lynch, on the lane to Broom's green and Ryton, was later replaced by farm outbuildings. (fn. 185) Hillash, west of the Ledbury road, was owned and occupied by the Hill family in the mid 16th century. (fn. 186) Its 18thcentury farmhouse became a private house in the 1850s. (fn. 187) Wilton Place, a large 18th-century house east of the road, replaced a farmhouse known as the Farm presumably on the spot where the Wilton family lived in the 16th century. (fn. 188) Farm Mill, on the river Leadon to the north-west, has a 17th-century house and remained a working mill until the 20th century. (fn. 189)

Ockington There was settlement to the east at Ockington in the early 13th century. (fn. 190) Its main farmhouse, owned by the Weale family for much of the 18th century, (fn. 191) was rebuilt as a private house in the 1980s. (fn. 192) The house next to it at Burtons, (fn. 193) occupied as two cottages in the mid 19th century, (fn. 194) was replaced by a new farmhouse in the early 20th century. (fn. 195) Hill Farm (formerly the Hill), on a hillside further east, was a copyhold of Dymock manor that belonged to the Hill family in the early 17th century. (fn. 196) Among the property that the Cams acquired from the Holmes family in the early 18th century, (fn. 197) it has late 17th-century outbuildings and an 18th-century house. (fn. 198)

To the south, beside the lane from the Lynch to Ryton, there is a moated site in a field known as Knight's Meadow. (fn. 199) Further along the lane there was encroachment on Knight's green in the mid 18th century (fn. 200) and one of two houses standing there in the mid 19th century (fn. 201) was a copyhold of Dymock manor. (fn. 202) Further east the house at a farmstead called Oysters (Heisters) was demolished before 1775 but its barn remained in use. (fn. 203)

Vell Mill in the fields beside the river Leadon to the south had medieval origins and a mill operated there until the early 18th century. (fn. 204) Its house, which belonged to Oxenhall vicarage from 1818, (fn. 205) was enlarged in the later 20th century. In the late 17th century Edward Puckmore, a wheelwright, built a house to the north-east, on the lane from Dymock village to Ryton; it was also known as Vell Mill, sometimes as Little Vell Mill. (fn. 206) In the late 19th century a pair of estate cottages was built to the west near Elm bridge. (fn. 207) Further east Callow Farm, an ancient farmstead on the far side of a hill next to the Leadon, has a house dating from the late 16th century and was part of the Madresfield estate for much of the 19th. (fn. 208) A homestead called Shayles abandoned after the late 1680s was a copyhold of Dymock manor and stood by the way from the Ketford river crossing to Ryton. (fn. 209) Ryton Ryton from where a local landholder in the mid 13th century took his name, (fn. 210) is made up of a hamlet strung out along a lane leading northwards towards Ledbury from Ketford bridge and more widely scattered cottages lower down to the west in the valley of a tributary of the Leadon followed by the M50 motorway. There are several early dwellings on a lane leading from the southern end of the hamlet towards Broom's green. At least one (no 333) dates from the late 16th or early 17th century. A smaller house (no 331), standing to the north beyond the motorway, is older. (fn. 211)

At the hamlet's south end, high up to the east of the lane from Ketford, a small timber-framed cottage and an adjacent stone building made three cottages known as the Gallows in 1901. (fn. 212) Adapted as a single dwelling in the early 20th century, they fell into ruin and were rebuilt as a house at the end of the century. (fn. 213) To the north used to be a copyhold farmhouse known in 1666 as the Line (fn. 214) and a tiny cottage called the Round House that was removed in the late 19th century from an island at a junction with a lane to Redmarley. (fn. 215) Limetrees Farm (formerly the Line Tree) (fn. 216) became part of the Madresfield estate in 1811 (fn. 217) and was the largest farmstead on the lane in the mid 19th century. (fn. 218) Two pairs of council houses were built at the north end of the hamlet in the mid 1930s (fn. 219) and a few private bungalows have been built elsewhere on the lane. Half way along the lane's west side a cottage formerly attached to a smithy (fn. 220) was rebuilt in 2002.

Ketford The hills of the east end of the parish overlooking the river crossing at Ketford are more sparsely populated than the rest of Dymock. (fn. 221) Walter of Ketford, a tenant of Dymock manor in the early 13th century, (fn. 222) had property in Little Ketford (fn. 223) and Robert Ketford had a house in the parish in 1373. (fn. 224) In the 18th century the two principal farms, centred on Great Ketford and Hill Place, were taken into the Yate family's estate and merged. (fn. 225) Great Ketford (later Ketford Farm), (fn. 226) which has survived, is set back from the Leadon below the crossing and has belonged to the Madresfield estate since 1810. (fn. 227) Upstream of the crossing a mill house was taken into the Madresfield estate in 1866 (fn. 228) and was rebuilt before 1882. (fn. 229)

Of the few dwellings in the side valley to the northeast, only Berrow's Farm, which was taken into the Madresfield estate in 1869, (fn. 230) remained in the late 19th century and it was abandoned in the 20th century. (fn. 231) A cottage further north, in a place known both as Winter's Land and Little Ketford, (fn. 232) was demolished in the mid 19th century. (fn. 233) The farmstead at Cut Mill, at the bottom of the valley near the Leadon, was the site of a medieval mill. (fn. 234)

Lintridge In the far north-east of the parish Lintridge Farm was formerly known as Little Lintridge. (fn. 235) Originally a copyhold of Dymock manor, it was the sole farmstead there from 1858 and belonged to the Madresfield estate from 1868. (fn. 236) Some way to the west is a pair of 20th-century farm cottages. A little to the south-east stands the surviving part of the house of Great Lintridge, (fn. 237) occupied after 1858 as cottages. (fn. 238)

Bromesberrow Heath Much of the nearby village of Bromesberrow Heath stands on the former common of Bromesberrow heath. At least one homestead stood on or by the heath in the early 16th century (fn. 239) and piecemeal encroachment on it increased in the 18th century. (fn. 240) In the mid 19th century some 40 small cottages were scattered randomly on the common. (fn. 241) Most were south of the turnpike road running east–west across the heath but in the west, where the common extended northwards into Bromesberrow, building had spilled over the parish boundary. (fn. 242) Although the common was inclosed in the late 1850s, few new houses were built until the early decades of the 20th century (fn. 243) and there were 50 or so dwellings in 1965. (fn. 244) More houses and bungalows were built in the 1970s, most south of the road, (fn. 245) and new building continued in 2002. A small business park has been created to the south-west between the village and the farmstead of Heath Farm.

Several farmsteads stood by the road leading west from the heath. At Great Heath, part of William Gordon's Haffield estate in the 1820s, (fn. 246) a pair of cottages was built west of the farmstead in 1861 and the farmhouse was later demolished. (fn. 247) In 1862 the estate's owner, W.C. Henry, built a school church nearer the heath opposite the drive to Haffield, in Ledbury (Herefs.). (fn. 248) After the school's closure in 1951 it was used as a piggery before being restored as a house in the 1980s. (fn. 249)

Broom's Green Higher up to the west, Broom's Green is a hamlet strung out along both sides of the road over a former green. Most of its houses and cottages, which numbered just over a score in the mid 19th century, (fn. 250) date from the 18th or 19th century but at its east end Laurel Farm stands on the site west of the Ryton lane of a house known as Hunts in 1411 (fn. 251) and White's Farm, further east, has a 17th- or 18thcentury timber-framed barn. (fn. 252) Towards the west end a timber-framed house probably of the late 17th century is set back north of the road on the edge of the former green. (fn. 253)

Greenway Further west on the road Greenway is a cluster of dwellings around the crossroads on the Dymock–Ledbury road. On the west side the Old Nail Shop, built in the 16th or 17th century, (fn. 254) was occupied by a nailer in the early 19th. (fn. 255) On the east side Stone House (formerly Longtown Hall) has an early 19th-century front and was two dwellings in the mid 19th century. (fn. 256)

Leadington

Pound Farm, standing between the river Leadon and the Preston brook north of Dymock village, was the principal house on the estate of a branch of the Cam family in the late 16th century. (fn. 257) Further north Greenway House, standing north of the road that runs westwards from the river, was formerly known as the Green House and was part of a farmstead long owned by the Hankins family from 1411. (fn. 258) The house at Drew's Farm, immediately to the south across the road, was enlarged in the early 20th century. (fn. 259) Bellamy's Farm, slightly lower down to the north-east, was presumably the centre of George Bellamy's estate in the late 14th century. (fn. 260) Its house, which had a new wing in 1739 and was later rebuilt, (fn. 261) stands inside a moat with an earlier barn among farm buildings outside. (fn. 262) Leadington Farm (also called Leadington Place), owned by the Hodges family in the 18th century, was a farmstead a little to the north-west. (fn. 263)

Tiller's Green To the south the hamlet of Tiller's Green is scattered randomly over a green beside the Much Marcle road. There was a homestead there in the mid 17th century (fn. 264) and squatter cottages were among a dozen dwellings on the green in the mid 19th century. (fn. 265) A small house was built further south on the road soon afterwards. (fn. 266) Several cottages in the hamlet have been enlarged and a bungalow was among a few new dwellings built there in the later 20th century.

At Windcross, where the Much Marcle road crosses the road to Leominster, a 17th-century cottage with a thatch roof stands north-west of the crossroads. (fn. 267) A later timber-framed farmhouse to the south-east below the main road was enlarged in 1962. (fn. 268) Further west on the Much Marcle road Hill Grove was built in the place of a farmstead known alternatively as Lady Grove and the Bush (fn. 269) for James John Wynniatt in the 1860s. (fn. 270) In the later 20th century six houses and bungalows were built next to it.

The Leadington The north end of the parish beyond Greenway House rises on the west side of the river Leadon, besides which Roman remains have been identified, (fn. 271) and contains many medieval homesteads. In 1539 Thomas Wynniatt lived at Upham and his younger namesake at Judgements immediately to the west. (fn. 272) Upham House, to the east, is a villa built in the 1830s by the owner of Upham farm (fn. 273) and let from the early 1860s as a private house. (fn. 274) Near by is a cluster of three early farmsteads east of the Ledbury lane. Haytraps, a copyhold of Dymock manor owned by the Gamond family in the mid 16th century, (fn. 275) was inhabited in 1287, Swords bears a name used locally as a surname at that time, (fn. 276) and Mirabels was presumably the centre of Richard Amyrable's estate in the late 14th century. (fn. 277) In the mid 19th century there were four small cottages to the south at Tillputsend, two on opposite sides of the Ledbury lane and an 18th-century pair on the lane to Hallwood green. (fn. 278) Two new cottages were built there later, the first by Thomas Gambier Parry after 1863, (fn. 279) and one was pulled down before 1963. (fn. 280) Two of the remaining dwellings were enlarged in the early 21st century.

Further north the farmhouse at Henberrows was rebuilt in the 19th century. Little Iddens, west of the Ledbury lane, is a small 17th-century farmhouse and the house at Glyniddens, to its north, was built in 1830. (fn. 281) Some of the scattered cottages or small farmhouses in the Oldfields area to the west and in the fields to the east (fn. 282) have been demolished and others have been modernized and enlarged. (fn. 283) A cottage on the east side at the site of a homestead called Hazards in the mid 17th century (fn. 284) had been abandoned by 1920. (fn. 285) A pair of cottages built on the lane by Gambier Parry (fn. 286) has been converted as a single dwelling.

Among the farmsteads that stood lower down towards the Ludstock and Preston brooks Lower House and several others that were all owned by the Hooper family in the late 17th and 18th century (fn. 287) have been abandoned almost without trace. To the south the homestead at New House, near the Preston brook on the lane to Hallwood green, was established following a small inclosure of open-field land not long before 1739. (fn. 288) Further south the farmstead at Rosehill, on the east bank of the Preston brook, was in the part of the Old Grange estate tenanted by the Wynniatt family in the late 16th century. (fn. 289)

Netherton There were at least two households at Netherton, in the open land west of the Preston brook, in the early 14th century. (fn. 290) The farmstead at Great Netherton, presumably the site of John Wills's house in the mid 16th century, (fn. 291) was the centre of an estate created by Robert Holmes in the mid 17th century. (fn. 292) Little Netherton, to the north-west, has also been known as Lower Netherton. (fn. 293) The farmstead there, perhaps that occupied by John Wynniatt in the early 16th century, (fn. 294) served an estate acquired by the Fawke family in the late 18th century. (fn. 295) In the 1860s a villa was built on the Leominster road to the north and in the following decade a farmhouse (Cropthorne Farm) was built near by, next to the lane from the Leadington to Hallwood green. (fn. 296) A pair of council houses was built near the farmhouse in 1934 (fn. 297) and a bungalow was erected next to them in the 1950s. (fn. 298)

Hallwood Green Hallwood Green is a small hamlet that grew up in the north-west corner of Dymock next to Much Marcle on waste land known sometimes as Hollister's or Hollis's green. (fn. 299) There was settlement there in the 1670s, when the place was known as Hollowshuttes green, (fn. 300) and more building took place in the 18th century as squatters encroached on the green, six encroachments being reported in 1765. (fn. 301) The hamlet was bypassed by a new road into Herefordshire in the 1830s and it contained a score of dwellings (fn. 302) when, in 1848, parts of the green were inclosed. (fn. 303) It remained a backwater mostly of thatched cottages in the early 1940s. (fn. 304) In 1948 three pairs of council houses were built on the lane to the east (fn. 305) and in the later 20th century private bungalows and houses were erected by the green and some older houses were rebuilt.

BUILDINGS

Amongst the farmsteads and cottages which stand along Dymock village street and throughout the parish, building patterns and methods are consistent. Timber framing, often with brick infill in the 17th century, gave way to brick with stone slate or tile for roofing in the 18th. A long phase of rebuilding in the 17th century was followed by another phase between the mid 18th and mid 19th century, when distinctive two-storeyed, three-bayed farmhouses, usually with casement windows under segmental heads, were built and farmhouses were improved by adding extra storeys and service wings, remodelling façades, and building cider houses and other farm buildings. The ebb and flow of building activity is evident particularly among the main houses on Dymock's manors and larger farms. (fn. 306) Several dwellings have evolved into small country houses.

Dymock Village

The village street is lined with buildings from end to end but before the 19th century farmhouses and cottages were scattered along it. None of the farmhouses are now used for that purpose, although the White House, opposite the church, retains some farm buildings.

At the western end the Old Cottage and Wood's Cottage are late medieval cruck-framed houses, the former originally with two rooms. (fn. 307) The box-framed Laburnum Cottage is of similar size and was built probably in the 16th century. (fn. 308) No other early houses survive in the street but some of the fabric of the White House, which in the late 17th century with 9 hearths was the largest establishment in the village, (fn. 309) was incorporated in plain rebuilding of the house in the mid 18th century. In the early 19th century its front wall was raised to allow a storey of windows to light the attic, accommodating a cheese store, a new western wing containing a brewhouse and dairy was added, and a timber-framed outbuilding was rebuilt as stables and a cider house. (fn. 310) A barn burnt down in 1890. (fn. 311)

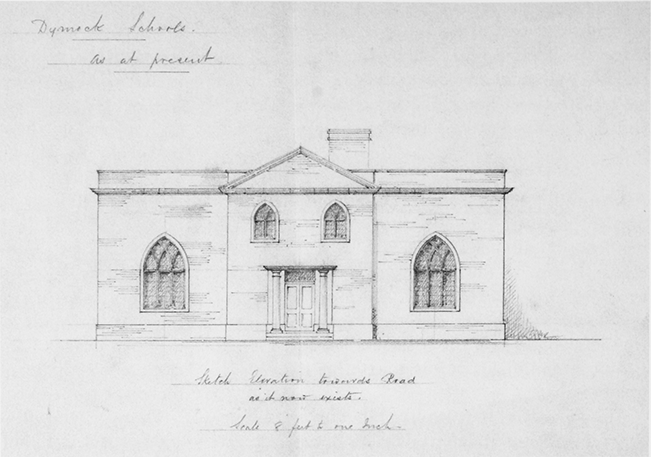

The work at the White House was part of a transformation of the village in the 18th century and the early 19th. Red brick was used both for new work and for remodelling existing property. Building work at the vicarage house (since demolished) included in 1806 a cider house with a granary over it. (fn. 312) Among the more ambitious designs was that by Richard Jones of Ledbury for Ann Cam's school, built in 1825. It combined Gothic and classical elements in a façade that screened the teachers' house and flanking schoolrooms. (fn. 313) High House, the largest and most prominently sited new house, was owned until 1771 by Revd James Brooke of Pirton (Worcs.). (fn. 314) Plain and urban in style with polychrome brickwork seen most clearly on its eastern end, it had five bays, three storeys, and a basement: in the early 19th century the windows on the façade were lengthened and reglazed. The house at Great Wadley was created in chequer brick soon after 1806 in a development that included rebuilding an adjacent structure as the George inn; the datestone on Great Wadley records its purchase in 1884 by the 6th Earl Beauchamp. (fn. 315) Several other buildings had rubbed brick dressings and classical doorcases.

New building in the mid 19th century is represented by Stoneberrow Place, a terrace of three composed c.1840 to look like a single house. (fn. 316) An early 18th-century cottage was refronted to make Stoneberrow House. (fn. 317) A more substantial change took place at High House, which in becoming the vicarage house in 1878 (fn. 318) was doubled in size to the north, the original staircase being incorporated in the new work, and in 1884 Ann Cam's school was extensively remodelled to plans by Waller, Son, & Wood of Gloucester. (fn. 319) The only substantial brand new building late in the century was the police station of 1898 built on the Kempley lane to look like a suburban villa. (fn. 320) During the 20th century building activity was mainly restricted to small houses and bungalows in gaps in the street frontage. Among those designed by Jean Elrington for Newent Rural District Council in the 1960s was an estate of 18 houses and 3 bungalows. (fn. 321) The Rectory, built as the parsonage in 1953, is in a neo-Georgian style. (fn. 322)

32. Greenway House: the south front

Outlying Farms and Cottages

Although many of the farms scattered throughout the parish are on medieval sites, almost none has medieval fabric. At Little Netherton the core of the house, which contained a truncated cruck and perhaps dated from the 15th century or early 16th, (fn. 323) was rebuilt in the 1980s. (fn. 324) A two-bayed medieval hall was part of the house at Berrow's Farm that fell into ruin in the 20th century. (fn. 325) A small farmhouse at Ryton (no 331) has a cruck truss.

Some cottages or small farmhouses, such as the Old Nail Shop at Greenway and no 333 at Ryton, were built in the late 16th or 17th century with 1½ storeys. (fn. 326) One at Castle Tump had an original plan with two rooms and staircase against the central partition in 1989. (fn. 327) During the 17th century much rebuilding with square panelled timber framing was undertaken. At Little Netherton the house was extended by one bay and timber-framed outbuildings were built. Some of the farmhouses of that time, for example Little Iddens and Allum's, seem to have been plain rectangular houses of two or three units and two storeys. Among others with more elaborate plans, New Rock, Swords, and Upham were each built on an L. At Swords a large cruciform chimneystack is at the rear of the hall range, whereas at Upham the hall range is heated from one end and a dog-leg staircase rises in a tower in the angle with the cross wing, which retains wattle and daub infill. A T plan was used for the tall house at Great Woodend (fn. 328) and for the house at Lintridge Farm. (fn. 329) The farmhouse at Ockington, probably one of the largest mid 17th-century houses not associated with one of the manors or principal estates, was built as a substantial gentleman's residence of two storeys and H plan with asymmetrical cross wings and a massive chimneystack at the rear of the hall range. In the late 17th or early 18th century some of it was reclad in brick and a cider house with granary over was built.

Greenway House may have been built in the later 16th century with an L or H plan, of which a twostoreyed hall range and southern cross wing survive. The room above the hall was originally open to the roof which has some windbraces and was heated by one of the four diamond-set brick chimneys on the stack at the rear of the hall range. In the later 17th century or the early 18th the wing was widened, reroofed and faced in brick, the hall range was refaced and partly reroofed, and a detached two-storeyed cider house with brick cellar was built. In 1776 the building of a northern wing, perhaps in place of a service end, made the house a smart home for its owner Thomas Hankins. (fn. 330) Venetian and Diocletian windows in the wing's front elevation lit a reception room and bedrooms above, (fn. 331) and the rest of the wing was filled with a fashionable staircase. In the 19th century the house was enlarged by the addition of a dairy and a later stone extension at right angles to the southern wing. The western end of that wing appears to have been added as a kitchen slightly later and a bell turret was added to the gable, either when the house accommodated a school (fn. 332) or afterwards.

33. Hillash: the east front in 1975

The high quality 18th-century building work at Greenway House included stone dressings, unusual for a farmhouse in an area where dressings were then usually of brick, as for example at the three-storeyed New House, which has segment-headed windows, paired on the ground floor, and band courses. The three-bayed houses at Hill Farm and Ketford Farm, the latter with its original rear outshut, seem to be the result of mid 18th-century rebuilding. At Hill Farm, where in 1648 the house had a chamber over a buttery and a closet called the study over a porch, (fn. 333) a detached timber-framed cider house and barn, the former of two storeys, were built not long before the house was rebuilt. (fn. 334) At Hillash, which was rebuilt as a superior farmhouse in the 18th century with four bays, 2½ storeys, and an elaborate well staircase, the façade was rendered and given a Doric portico in the early 19th century. (fn. 335) Low service ranges were added then (fn. 336) and new building after 1852, when it became the country house of Thomas Holbrook, included an entrance lodge. (fn. 337) The house at Pitt House Farm, made by knocking two dwellings into one by 1736, was known for a time as Edulus Place (fn. 338) and in 1795 its rooms included a hall and several parlours and its farm buildings a dairy house with an upper cheese room, cider houses, two barns, and cow sheds. (fn. 339)

Several houses were completely rebuilt in the first half of the 19th century. At Haytraps, which in 1622 had a hall range with parlour next to it and a cross wing with three rooms and attics, (fn. 340) the 18th-century pattern of a three-bayed front with segmental headed windows was developed. Mirabels followed the same model but has a second, later pile of rooms and large outbuildings. The new house at Crowfield Farm incorporated early fabric. (fn. 341) Glyniddens, built in 1830 for Joseph Davies (fn. 342) in late Georgian style with sash windows, the larger Upham House, built slightly later for William Chichester (fn. 343) with a symmetrical three-bayed front and porch, and Heath Farm, which has a symmetrical five-bayed rendered front and Ionic porch, imitated fashionable villas.

Many small improvements to houses and farm buildings were carried out in the early 19th century. At Allum's, where rebuilding had begun in the 18th century, the house's easternmost room was replaced by a brick range set at right angles to form an L plan with a three-bayed entrance façade facing east, a central staircase, and a rear outshut. An additional wing with outside stairs to a probable cheese room had a cider house and cellar at one end where the ground drops to a farmyard cut out of the slope. A timber-framed barn stands at the upper level and there are animal sheds around the yard. At Little Netherton the house's T plan includes a two-bayed brick-faced block with hipped roof built in 1843 above a stone basement. (fn. 344) Later barns, one large and one small, are dated 1860 and 1861 respectively. Improvements were also carried out at New Rock, where a cider house was added to the rear of the cross wing. Among new buildings provided in the 1860s and 1870s for farms on the Madresfield estate (fn. 345) was an outbuilding at Limetrees Farm in 1877. (fn. 346)

Among the more radical changes in the 20th century, the upper storey and the interior of the house at Ockington were reconstructed and a number of its barns and other outbuildings were removed in the mid and late 1980s. (fn. 347) At Hillash the house was extended as a nursing home in the late 1980s and outbuildings were converted as residential accommodation. (fn. 348)

MANORS AND ESTATES

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Dymock was a major royal estate in which there was a possible intrusion shortly after the Norman Conquest. In the 12th century parts of the manor were granted to Flaxley abbey and William de Gamages to create two new manors, known later as Old Grange (or Dymock) and Little Dymock (or Gamage Hall). The manor of Dymock, occasionally called Great Dymock, (fn. 349) finally passed from royal hands in the later 13th century. The history of the manor of Rye, mistakenly regarded as part of Dymock, (fn. 350) has been given under Tirley, in an earlier volume. (fn. 351)

In the 14th century Dymock contained numerous farms including freehold and copyhold land held under the manors of Dymock and Little Dymock. (fn. 352) Many belonged in the 16th century to yeoman families that retained them for generations. (fn. 353) In the early 17th century the largest estate, based on the Old Grange, passed together with Little Dymock to the Wynniatt family. An estate amassed by a branch of the Cam family was broken up after 1790, part going to the Thackwells, and in the mid 19th century the Wynniatts (1,036 a.) and the Thackwells (657 a. and 417 a.) remained the principal landowners. At that time the rest of the parish was divided between well over forty estates or farms and the Lygons (the Earls Beauchamp) of Madresfield, who first purchased land in Dymock in the early 19th century, were one of four other families with 300 a. or more. The other estates were 13 holdings of between 100 and 200 a., 9 of between 50 and 100 a., 12 of between 20 and 50 a., and numerous smaller holdings. (fn. 354) The larger estates were broken up by sales in the early and mid 20th century. (fn. 355)

DYMOCK (GREAT DYMOCK) MANOR

Four years after the Norman Conquest the estate at Dymock that had belonged to Edward the Confessor, and was assessed at 20 hides, passed to William FitzOsbern, earl of Hereford. William, who possibly acquired the estate without royal consent for the Domesday jurors were ignorant of his title, died in 1071 and was succeeded at Dymock and in the earldom by his son Roger of Breteuil. Roger forfeited his estates by his rebellion against the king in 1075 and the manor remained in royal hands (fn. 356) probably until it was acquired by Miles of Gloucester. Miles, who was created earl of Hereford in 1141, died in 1143 and the manor and the earldom passed to his son Roger, (fn. 357) who gave part of Dymock to his foundation of Flaxley abbey. (fn. 358) The manor was among former royal demesne estates that Henry II confirmed to Earl Roger in 1154 or 1155 (fn. 359) and granted to Roger's brother Walter of Hereford following the earl's rebellion and death in 1155. (fn. 360) On Walter's death c.1160 the manor reverted to the Crown (fn. 361) and in 1200 it was among the estates in which Henry de Bohun, heir to the earls of Hereford, quitclaimed all his rights on becoming earl. (fn. 362) Richard I had granted another part of Dymock to William de Gamages. (fn. 363)

The manor, which Walter de Clifford the younger held by grant from King John in 1216, (fn. 364) was taken in hand for the Crown in 1221 or 1222 (fn. 365) and was granted in 1226 to the leading inhabitants (probi homines) at a fee farm. (fn. 366) They farmed the manor until 1244 or 1245, when it was granted to Morgan of Caerleon, (fn. 367) and Ela Longespée, countess of Warwick, held it under royal grant from 1249. (fn. 368) Ela, who in 1251 was awarded free warren on her demesnes, (fn. 369) married Philip Basset and with him granted the manor in 1257 to Flaxley abbey for her lifetime, the abbey paying an annuity of £50 to her and a stipend to her chaplain serving in the parish church. (fn. 370) Philip, who was justiciar from 1261 to 1263, died in 1271 (fn. 371) and Ela had surrendered the manor to Edward I by 1287, when he granted her a £50 annuity in return (fn. 372) and gave the manor in exchange for two Sussex manors to William de Grandison, his wife Sibyl, and her heirs. (fn. 373) William was dead by 1335 and his son and heir Peter de Grandison (fn. 374) held Dymock manor at his death in 1358. Peter was succeeded by his brother John, bishop of Exeter, (fn. 375) and John (d. 1369) by his nephew Thomas de Grandison. (fn. 376)

At Thomas's death in 1375 the manor was divided between his aunts' descendants with a third going to William de Montagu, earl of Salisbury, another third to John Northwood, and the other third to Roger Beauchamp, Thomas Fauconberge, Alice wife of Thomas Wake, and Catherine widow of Robert Todenham. (fn. 377) Thomas Fauconberge's share, forfeited by his support of the king's enemies in France, was the subject of grants from 1377 until Thomas secured possession in 1406. (fn. 378) Roger Beauchamp's share passed at his death in 1380 to his son or grandson Roger Beauchamp. (fn. 379) Roger Northwood, who succeeded his father John (d. 1379), (fn. 380) and John Todenham, who succeeded his mother Catherine (d. 1383), (fn. 381) sold their shares to Richard Ruyhale and his wife Elizabeth by 1394. (fn. 382) William de Montagu sold his share by 1395 to his nephew Richard de Montagu (fn. 383) (d. 1429), who granted it in 1407 to Richard Ruyhale in return for an annuity. (fn. 384)

Richard Ruyhale died in 1408 holding two thirds of his estate, called the manor of Dymock, jointly with his wife Elizabeth and leaving an infant son Richard as his heir. (fn. 385) The younger Richard died a minor in 1415, (fn. 386) and in 1421 Elizabeth and her then husband Richard Oldcastle obtained a grant of the manor from Edmund Ruyhale, the younger Richard Ruyhale's uncle and heir. (fn. 387) Richard Oldcastle died childless in 1422 (fn. 388) and on Elizabeth's death in 1428 the manor reverted to Edmund Ruyhale's trustees and passed to John Merbury, (fn. 389) a chief justice in south Wales, (fn. 390) who in 1432 acquired the interest in the manor that had descended from Alice Wake to Thomas Wake of Blisworth (Northants.). (fn. 391)

John Merbury died in 1438. His daughter and heir Elizabeth, wife of (Sir) Walter Devereux, (fn. 392) survived in 1453 (fn. 393) and Walter died in 1459, having settled the manor on Anne, the wife of his son Walter, later Lord Ferrers. Following Anne's death in 1469 Walter held the manor by courtesy and after his death at the battle of Bosworth in 1485 his widow Jane (or Joan) took possession of it. She married in turn Thomas Vaughan (fl. 1492), Sir Edmund Blount (d. 1499), and Thomas Poyntz (fn. 394) of Alderley, who held the manor in her right in 1522. (fn. 395) By 1537 the manor had passed to Anne and Walter Devereux's grandson Walter Devereux, Lord Ferrers. (fn. 396) Walter, who was created Viscount Hereford in 1550, died in 1558 and was succeeded by his grandson Walter Devereux, who was created Lord Bourchier in 1571 and earl of Essex in 1572. He left the manor at his death in 1576 to his widow Lettice. (fn. 397) She married in turn Robert Dudley (d. 1588), earl of Leicester, and Sir Christopher Blount (ex. 1601) (fn. 398) and retained the manor in 1604. (fn. 399)

In 1606 the manor was acquired by Giles Forster, (fn. 400) the owner of Boyce Court. (fn. 401) In 1611 Giles conveyed the manor to Sir George Huntley (fn. 402) (d. 1622). His son and heir William Huntley (fn. 403) was lord in 1631 (fn. 404) but the manor court was held in the name of Giles Forster, his relative, in 1633 (fn. 405) and of John Stratford in 1638. (fn. 406) In 1640 the owner was Sir John Winter of Lydney, also a relative of the Huntleys. (fn. 407) Sir John, a prominent royalist, suffered heavy financial penalties after the Civil War (fn. 408) and in 1656 he sold the manor to Evan Seys (fn. 409) of Boverton (Glam.). Evan, who was MP for Gloucester after the Restoration, (fn. 410) sold it in 1680 to Edward Pye of Much Dewchurch (Herefs.). (fn. 411) Edward, a merchant with business in Barbados, died in 1692 having settled the manor in trust for his grandnephew Edward Pye Chamberlayne. Edward, who lived for a time on Barbados, (fn. 412) took possession in 1704 (fn. 413) and gave the estate to his son Edward Pye Chamberlayne in 1717. (fn. 414) The latter died in 1729 and his widow Elizabeth held the estate as guardian of their infant son Edward Pye Chamberlayne until 1740. (fn. 415) The son sold the manor and the rest of the estate in 1769 to Ann Cam of Battersea (Surrey), (fn. 416) heiress to other lands in Dymock. (fn. 417)

Ann Cam died in 1790 (fn. 418) leaving the manor with part of her estate to John Moggridge of Bradford-onAvon (Wilts.), a clothier. (fn. 419) John (d. 1803) was succeeded by his son John Hodder Moggridge (fn. 420) and he sold the manor in 1811 to Samuel Beale. (fn. 421) By 1812 Samuel had sold it to William Lygon, Lord Beauchamp of Powick (Worcs.), (fn. 422) who had already added several farms in Dymock to his estate at Madresfield in Worcestershire. (fn. 423) William, who was created Earl Beauchamp in 1815, died in 1816 (fn. 424) and his successor at Madresfield owned c.550 a. in Dymock in the mid 19th century. (fn. 425) Most of that land was sold c.1919 but William Lygon, the 8th earl, retained the lordship of the manor in the mid 1960s (fn. 426) and the Madresfield estate included a farm at Ketford in 2002.

OLD GRANGE MANOR

Roger (d. 1155), earl of Hereford and lord of Dymock, (fn. 427) included the Dymock demesne and half of the Dymock wood in his endowment of Flaxley abbey. Henry II confirmed the gifts in 1158 (fn. 428) and William de Gamages later granted the abbey other land in Dymock. (fn. 429) The abbey retained its estate based on a grange (later the Old Grange) on the west side of the parish until the Dissolution (fn. 430) when, in 1537, its possessions were acquired by Sir William Kingston. (fn. 431)

Sir William died in 1540 and his son and heir Sir Anthony Kingston (fn. 432) sold his Dymock property to Thomas Wenman in 1544. (fn. 433) Thomas was later knighted and his son Thomas (fn. 434) settled the estate, known as the manor of Dymock or Old Grange, on himself and his wife Jane (or Joan) in 1570. Thomas and Jane later acquired the manor of Little Dymock and after his death in 1582 (fn. 435) she married in turn Thomas Fisher (d. by 1592) of Bampton (Oxon.) and Richard Unett of Woolhope (Herefs.). She died in the early 17th century and her estate passed to her granddaughter Jane, the daughter of Richard Wenman (d. 1598) and wife of John Wynniatt. (fn. 436)

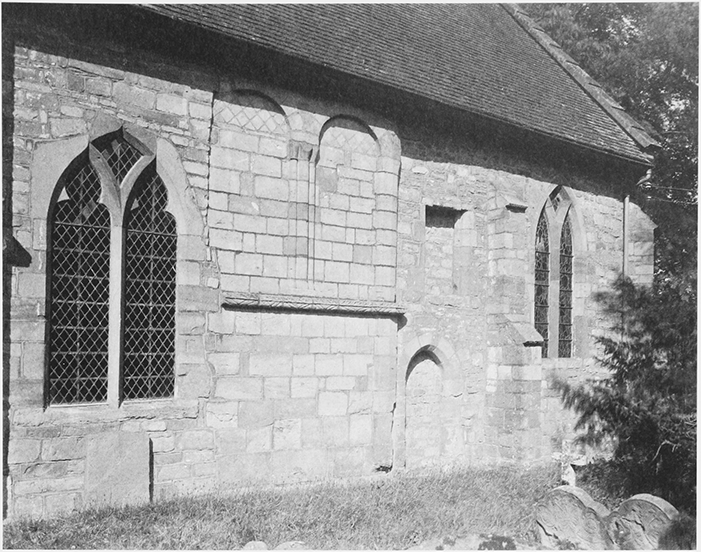

34. The Old Grange from the north-east in 1920, showing the medieval stonework on the east side

Jane Wynniatt died in 1633 and her husband in 1670. Their son Wenman Wynniatt (d. 1676) (fn. 437) was succeeded in the estate by his son Wenman, a minor. (fn. 438) He died in 1731 and after the death of his wife Penelope (fn. 439) in 1732 the Old Grange descended in the direct line to Reginald Wynniatt (d. 1762), (fn. 440) who inherited an estate on the Cotswolds at Stanton, (fn. 441) Revd Reginald Wynniatt (d. 1819), and Thomas Wynniatt (d. 1830). (fn. 442) Thomas left the Old Grange to his nephew Reginald Wynniatt, a minor. (fn. 443) At Reginald's death in 1881 it passed to his brother James John Wynniatt but his right of succession to the estate was quashed and Reginald's widow Caroline took possession. (fn. 444) She married Horace Drummond Deane and on her death in 1919 (fn. 445) the estate passed to Reginald's only child Harriett, who had married Henry Mildmay Husey. Under Harriett (d. 1944) (fn. 446) much of the estate was sold (fn. 447) and the Old Grange and its grounds, which passed to her son Ernest Wynniatt Husey (d. 1958), (fn. 448) had a succession of owners after their sale in 1965. (fn. 449)

The Old Grange stands south of the Kempley brook on the site of Flaxley abbey's grange and within a park created probably in the 19th century. (fn. 450) The core of the house is a late medieval stone dwelling, the home in 1522 of the abbey's servant John Wynniatt, (fn. 451) of which a section of high-quality ashlar has been incorporated in a canted projection on the eastern side. In the 17th century when it was both owned and occupied by the Wynniatts (fn. 452) the house was rebuilt and enlarged in brick with mullioned and transomed windows, the hall being subdivided and the roof raised as shown by the timber-framed north-eastern gable and beams inside. Some fittings of that period survive but not necessarily in situ. A stable court was built close to the southern end of the house. Piecemeal changes to the house in the 18th and early 19th century are difficult to interpret but they included the addition of a porch on the north entrance front and a loggia on the south end, both in Greek revival style, and the washing of the house to make it all look stone-built. (fn. 453) In alterations of 1896 the northern end was rebuilt and extended westwards to make a new entrance façade (fn. 454) and soon afterwards an east lodge was built on the Leominster road and an avenue planted along the drive between it and the house. (fn. 455) Farm buildings west of the house include a large 17th-century barn with a timber frame on a high stone plinth.

LITTLE DYMOCK MANOR

About 1197 Richard I granted part of Dymock manor to William de Gamages. (fn. 456) William's estate, which perhaps remained in his possession in the mid 1230s, (fn. 457) passed to Godfrey de Gamages (d. c.1253) (fn. 458) and was inherited by Godfrey's daughters Elizabeth and Euphemia, minors who married Henry of Pembridge and William of Pembridge repectively. (fn. 459) William and Euphemia held the estate or manor, assessed as ½ knight's fee, in 1285 (fn. 460) and William held it by courtesy after her death. In 1317 it passed to their son William (fn. 461) and in 1342 he granted it to his son Henry and his wife Margaret. (fn. 462) The estate, based on Gamage Hall in the south-east of the parish, passed at Henry's death in 1362 to his son John, a minor, (fn. 463) and was later known as the manor of Little Dymock or Gamage Hall. (fn. 464) John (d. 1376) (fn. 465) was succeeded by his son John, who came of age in 1388. (fn. 466) The manor passed to the younger John's son Thomas and his son John (fn. 467) (d. 1505) was succeeded by his son Walter (fn. 468) and Walter (d. by 1515) by his daughter Elizabeth, who married (Sir) Roland Morton. (fn. 469) Roland survived Elizabeth and at his death in 1554 the manor passed to their son Richard Morton (fn. 470) (d. 1559), who was succeeded by his son Anthony. (fn. 471) After he sold the manor in 1571 to Thomas and Jane Wenman (fn. 472) it descended with the Old Grange, (fn. 473) John and Jane Wynniatt being lord and lady of the manor in 1631. (fn. 474) Revd Reginald Wynniatt reserved the manorial rights on selling Gamage Hall c.1770. (fn. 475) The house, which long had been occupied by tenants (fn. 476) and remained the manor court's meeting place, (fn. 477) is described below. (fn. 478)

OTHER ESTATES

Boyce Court

Boyce Court, formerly known as the Boyce, stands in the south of the parish near Dymock wood and in the 16th century was the principal house on an estate that previously had belonged to the du Boys (Boyce) family. In the late 12th or early 13th century Richard du Boys acquired from Flaxley abbey an assart of 4 a. between its wood and his land (fn. 479) and in the 13th century Walter du Boys held some of his land in Dymock of the fee of William Cauvey. (fn. 480) In 1299, Richard du Boys, a knight, granted two of his Dymock tenants their liberty (fn. 481) and in 1327 Edmund du Boys was assessed for tax in Dymock. (fn. 482) Walter Boyce, a freeholder in Little Dymock manor in 1385, (fn. 483) was possibly the Walter Boyce of Dymock who quitclaimed property in Bodenham (Herefs.) to Edmund Bridges and his wife Ellen in the early 15th century. (fn. 484) The Bridges family (fn. 485) also acquired land in Dymock, some through the marriage by 1457 to Maud, daughter and heiress of Thomas Henbarrow, of Thomas Bridges. (fn. 486) Their son William, who had a residence in Woodend division and was among Dymock's richest landowners, (fn. 487) died in 1523. (fn. 488) His son William lived at Boyce Court in 1530 (fn. 489) and John, another son, owned the estate, sometimes called a manor, in 1558. (fn. 490) John was succeeded by his nephew Humphrey Forster in 1561. (fn. 491) In 1604 Humphrey and his wife Martha gave the estate to their son Giles in return for an annuity (fn. 492) and in 1611 Giles sold it, together with Dymock manor, to Sir George Huntley. (fn. 493) Later in 1611 Sir George sold Boyce Court and its land to William Bourchier (fn. 494) (d. 1623), the lord of Barnsley manor who was succeeded by his son Walter (d. 1648). (fn. 495) Under Walter's will the manor of Boyce was sold in the early 1650s to Evan Seys, (fn. 496) later the owner of Dymock manor, with which Boyce Court passed, (fn. 497) becoming the residence of Edward Pye (d. 1692) and his successors (fn. 498) and descending after Ann Cam's death to John Hodder Moggridge. (fn. 499) John Drummond, who bought Boyce Court shortly before 1814, (fn. 500) died in 1835 (fn. 501) and his son John (fn. 502) inherited an estate that covered 321 a. of Dymock (fn. 503) and passed after his death in 1875 (fn. 504) to his daughter Georgiana Matilda (d. 1904) and her husband George Onslow Deane (d. 1929). Their son Horace Drummond Deane-Drummond (formerly Deane) died in 1930 and his son John Drummond Deane-Drummond (fn. 505) sold Boyce Court in 1935 to G.H. Goulding, a farmer. (fn. 506) The house belonged in 2004 to Goulding's daughter Sylvia. (fn. 507)

35. Boyce Court: the south front in 1975

Although Evan Seys was assessed for tax on 13 hearths in 1672 (fn. 508) the oldest surviving part of Boyce Court is a fragment of a two-storeyed brick house probably built in the early 18th century. That house, which incorporated fabric of the earlier house, (fn. 509) had an H plan with a south front of eight bays (fn. 510) and was probably double-pile. (fn. 511) In granting a lease in 1746 E.P. Chamberlayne reserved several rooms and outbuildings together with a new part of the house and a deep cellar. (fn. 512) In the early 19th century the eastern wing of the H was replaced by a larger neoclassical block and the principal 18th-century room was remodelled to match. The new block, rectangular and double-pile in plan with northerly projections, of which only the north-eastern is original, had a five-bayed stuccoed southern façade of 2½ storeys with a central porch and contained an entrance hall flanked by two large rooms. In the later 1930s it was altered slightly and all but three bays of the earlier house was demolished. (fn. 513)

The house stands close to the home farm in a park made picturesque probably when the house was enlarged in the early 19th century. (fn. 514) In the mid 18th century avenues led northward to the village and south-eastwards to the Newent road (fn. 515) and the grounds included a walled garden and a lower garden. (fn. 516) In the early 19th century wooded walks were laid out east of the house alongside the Hereford and Gloucester canal, cut through the park in the 1790s, (fn. 517) a stream was dammed to form an ornamental fishpond probably controlled to supply power to the farm buildings, and a drive was created running eastwards to a lodge on the Newent road. (fn. 518) Also in the 19th century a stable block was built and most of the farm buildings were replaced, all in brick. One timber-framed barn survives. The east lodge was rebuilt in 1865. (fn. 519)

36. Outbuildings at Callow Farm, showing ranges dated 1861 (right) and 1870

Callow Farm

Callow farm, in the east of the parish, was perhaps represented by the land that William Callow, a chaplain, held from Dymock manor in 1394. (fn. 520) It was occupied by the Shayle family in the early 16th century (fn. 521) and Thomas Shayle (d. 1540) left it to his wife Elizabeth with reversion to his son Thomas. (fn. 522) John Shayle (d. 1685) (fn. 523) of Redmarley was succeeded by his nephew Thomas Shayle, a Gloucester mercer who sold the farm (159 a.) in 1687 to Rice Yate of Bromesberrow. Rice (d. 1690) and his son Walter (d. 1744) acquired other farms in the east of Dymock (fn. 524) and in 1810 W.H. Yate sold them all to William Lygon, Lord Beauchamp, owner of the Madresfield estate. (fn. 525) About 1919 the estate sold Callow farm (248 a.) to its tenant farmer, A.H. Chew. (fn. 526) He died in 1947 (fn. 527) and the farm passed to his son R.S. Chew (fn. 528) (fl. 1964). (fn. 529) The brothers Malcolm and John Stallard bought it in 1978 and they farmed there in 2004. (fn. 530)

The two-storeyed farmhouse was built in the late 16th century on an H plan and has square-panel timber framing with intermediate close studding and, to the west, a high plinth and a cellar where the ground falls away to the north. The northern end of the east wing and the hall block, which has a stone northern stack with two diagonally-set brick shafts, seem to predate the western wing, which contained the parlour. That room has elaborately moulded beams and the wing a large stone stack with a pair of square-set chimneys. In the 19th century additional brick nogging was inserted in the frame and a singlestoreyed addition was built across the northern side of the hall, part of which, together with the end of the west range, was refaced in brick. In the 20th century the southern end of the east wing, which has two large chimneystacks, was replaced; evidence of weathering suggests that it had fallen into disrepair. A staircase was inserted in the hall range and a conservatory added to the front. Later in the century a northern porch was added, the timber-framed north wall of the eastern wing was rebuilt as original, and the windows were returned to their earlier 20th-century pattern. Internal subdivision in the wings created bedrooms, bathrooms, and an entrance passage.

The development of the farmyard to the east follows that of the house. A 17th-century barn on a high stone plinth has a timber frame with a wattle infill that was renewed in the late 20th century. A brick cheese room next to the house was altered in the early 19th century and the adjoining animal shelters and sheds forming a long L were completed by the Madresfield estate in 1861. Stables adjoining the barn were built in 1870. (fn. 531)

Gamage Hall

About 1770 Gamage Hall was detached from Little Dymock manor and bought by Richard Hall. (fn. 532) At his death in 1780 (fn. 533) the house passed with its land to his nephew Revd John Sergeaunt. (fn. 534) From John (d. 1780) it descended with Hart's Barn in Longhope to Richard Hall and in 1861 he sold the house with c.180 a. to Guy Hill, (fn. 535) owner and farmer of the Old Rock. Guy's son Henry (fn. 536) sold Gamage Hall farm to A.H. Chew in 1909 (fn. 537) and the county council bought 260 a. with the house in 1919. (fn. 538) The council remained the owner in 2003. (fn. 539)

The house at Gamage Hall was rebuilt in the mid 17th century as a two-storeyed timber-framed farmhouse with four hearths in 1672. (fn. 540) The squarepanelled frame is exposed inside and at the rear and original timbers have been incorporated in a south porch. In the 18th century the front, south wall of the eastern rooms, including the hall, was rebuilt in brick with segment-headed windows and in the early 19th century the rest of the south front was faced in brick and the house given sash windows front and back. A long partly timber-framed north-eastern wing, added in the late 17th or 18th century, has steps to a first-floor room, probably a cheese room.

Lintridge

In the mid 17th century Thomas Wall owned the estate or farm in the far north-east of the parish that became Great Lintridge. Thomas, the son of William Wall, (fn. 541) died in 1665. His son William, the county sheriff in 1682, (fn. 542) later lived in Ledbury and at his death in 1717 the estate passed to his grandson William Wall. (fn. 543) He sold it in 1727 to John Skipp of Ledbury and it was settled the following year on the marriage of John's daughter Jane and George Pritchard, heir to an estate at Hope End, in Colwall (Herefs.), and from 1749 owner of Dymock rectory. Great Lintridge descended with the rectory to Sir Henry Tempest Bt., (fn. 544) on whose separation from his wife Susan in 1815 it was sold to John Terrett of Hanley Castle (Worcs.). At his death in 1820 the estate (434 a.) passed to his widow Mary, later wife of Joseph Harris of Claines (Worcs.), but in 1824 trustees for John's creditors sold it to Joseph Hill, the owner of Little Lintridge. (fn. 545)

Little Lintridge was an estate centred on a house formerly called Tops Tenement, a copyhold of Dymock manor that had belonged to the Weale family. (fn. 546) The Weales farmed at Lintridge in the mid 17th century (fn. 547) and John Weale sold the estate or farm to Decimus Weale and his wife Rachael (née Benson) in 1721. Their children, Decimus, Elizabeth wife of Robert Symonds, and Rachael wife of Matthew Kidder, sold it in 1746 to Thomas Hill. Thomas, later of Bromesberrow, settled Little Lintridge on his son Joseph in 1769 (fn. 548) and from Joseph (d. 1800) it passed to his son Joseph. Joseph, the purchaser of Great Lintridge in 1824, was succeeded at his death in 1833 by his son Joseph (fn. 549) but in 1837 the representatives of Mary Harris (d. 1830) sold most of Great Lintridge (301 a.) to William Laslett of Worcester. William, who was elected MP for that city in 1852, released his estate to his sister Sophia Laslett in 1841 and she conveyed it back to him in 1851. (fn. 550) In 1858 he purchased Little Lintridge from Joseph Hill (fn. 551) and, having made its house the centre of his enlarged estate or farm, (fn. 552) sold it with 382 a. to Earl Beauchamp, owner of the Madresfield estate, in 1868. (fn. 553) The farm remained part of the Madresfield estate until c.1919 (fn. 554) and was owned by Mr Peter Sargeant in 2004. (fn. 555)