Pages 185-191

Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

CHAPTER VII. New River Estate: Introduction

Cows and wooden water pipes were all that occupied the fields around New River Head at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Fifty years later artists, doctors, lawyers, merchants and watchmakers were prominent among the thousands of residents of what had become a district of middling-sized stock-brick houses, neatly geometrized in a pattern of terraces, squares, and one of the handful of circuses to be laid out in London (Ill. 237). After another half-century the prosperous middle classes had largely moved away. For them the area held no apparent visual attractions, even the better addresses being judged as 'possessing no external beauty'. (fn. 1) Family houses had become sets of lodgings, and there was a large transient population, including on more than one occasion V. I. Lenin. Country Life, on the eve of the Second World War, reclaimed the area's early nineteenth-century town planning as 'delightful'. Despite bomb damage most of this townscape endured, and, in post-war reconstruction, even gained a new geometrical delight in the triaxial form of a major public housing project, Bevin Court. Then, with conservation legislation in place, the social compass swung back; at the beginning of the twenty-first century houses here change hands for more than £1m each.

237. Former New River estate, looking east in 2001. Great Percy Street and Percy Circus at centre and front, Myddelton Square with St Mark's Church at back

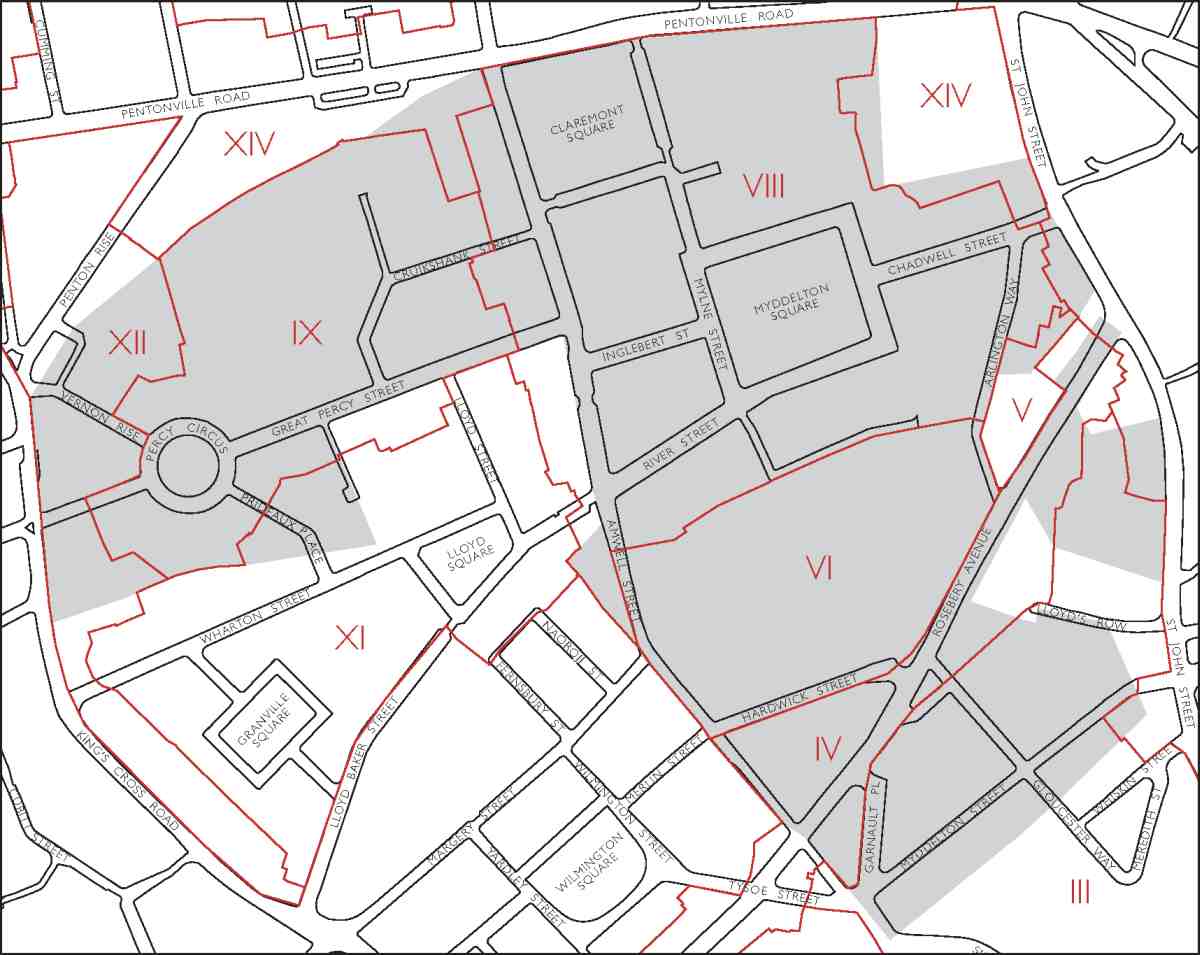

That, in a nutshell, is the story of one of Clerkenwell's largest estates. The New River Company's lands straddled almost the whole northern part of the parish, extending east to west from St John Street to King's Cross Road, and reaching from Pentonville Road in the north as far south as Myddelton Street. The detailed topography of this territory is largely covered in Chapters VIII and IX, small parts falling into other chapters, here and in volume xlvi (Ill. 238). The present chapter deals with the broader history of the New River estate, addressing its formation and, after a brief chronological overview, outlining its development and architectural character.

238. Map showing extent of New River estate (grey) and parts described in individual chapters

At the heart of the estate, both topographically and historically, is New River Head, established here in 1613 to provide London with water. The New River Company took more than a century to gain undisputed control of the fields around its waterworks, and there was no commercial impetus to build houses on them until after 1810. From that time the laying out of streets slowly began. Building became intensive in the 1820s, and again in the 1840s, and by 1853, when the estate was fully developed, about 650 houses had been constructed. Of these, somewhat fewer than half survive. The company's intention was to create an attractive residential district, spaciously laid out, with few small houses, and it worked hard to attract and then to retain respectable, essentially middleclass, tenants. At first it was largely successful, numerous professionals settling here in the 1820s and 30s. The better addresses were in Myddelton Square and Claremont Square, tradespeople being more strongly represented along the side streets, where there were rows of shops, as on Amwell Street and Arlington Way. In 1835 Charles Dickens strolled around the area looking at the new houses and found that 'They are extremely dear, the cheapest I looked at, being £55 a year with taxes. Their situation for business is undeniable certainly, and the houses themselves are very pretty, but this is too much'. (fn. 2) That proved to be the case. There were lodging houses from the outset, and by the 1840s fashion, never very firmly established, had shifted away from this part of London. Multiple occupancy gradually increased, becoming widespread by the end of the century, particularly in the later-built and lower-lying western addresses, in and around Percy Circus and Holford Square, though without, by and large, loss of respectability.

With the removal in 1904 of its primary purpose as a water supplier, the New River Company was re-formed as nothing more than a limited liability property company. Leases began to fall in soon after this, and the company undertook a major overhaul of its property in the years up to 1914, retaining direct management. There was some cautious addition of flats. Maisonette flats in 1909–10, infilling gardens on what is now Cruikshank Street, were followed by small blocks in the 1930s, in redevelopments on Prideaux Place and at Claremont Close. A few existing houses were also converted to flats, others turned over to commercial use. Some light industry had been admitted in the 1920s, behind Pentonville Road and as redevelopment near Rosebery Avenue. The district had become far from desirable residentially, very few houses remaining in single private occupation and some being badly overcrowded. Finsbury Borough Council would have liked to redevelop, and for Christopher Hussey's Country Life readership in 1939 the New River estate was, politely, 'off the beaten track'. (fn. 3)

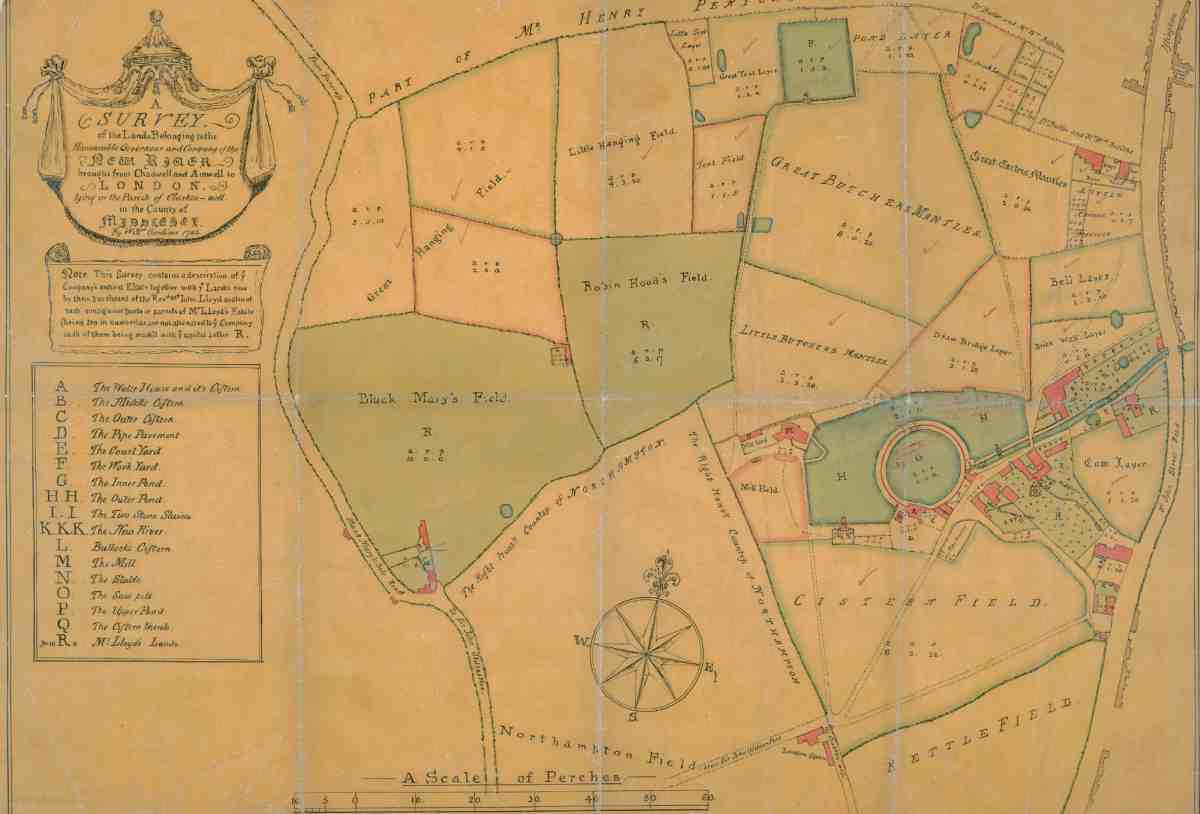

239. Map accompanying purchase agreement between New River Company and the Rev. John Lloyd, 1743

Just as the civilized qualities of the estate's townscape were coming to be appreciated the area suffered significant wartime losses. Some of these were made up by the New River Company, with 'facsimile' and other replacement flats in lieu of houses. Badly damaged, Holford Square was wholly replaced by Finsbury Borough Council's Bevin Court flats, and the company continued to build its own smaller blocks, on Arlington Way and Myddelton Passage. Much of what had survived the war to the east of Amwell Street had been 'listed' as early as 1950. Into the 1960s more houses were converted to flats, and some gardens were given up for rows of garages. In 1964 the New River Company sought permission to redevelop the whole of its estate east of Amwell Street, with proposals that included a 22-storey block on the site of Sadler's Wells. Finsbury Borough Council did not object, but in 1968 its successor the London Borough of Islington designated the New River Conservation Area. When the New River Company Ltd was taken over by Sir Max (later Lord) Rayne's London Merchant Securities in 1974 the borough acquired most of the residential estate for just over £4m. (fn. 4) There were further conversions as Islington Council refurbished more than 600 homes in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a process that considerably reduced densities, despite associated squatting. Since then right-to-buy legislation and the redevelopment of New River Head have facilitated gradual gentrification.

The estate before development

The estate was part of the Commandery Mantells, the extensive landholding which before the dissolution of the monasteries had belonged to the Knights Hospitallers. It was acquired by the New River Company in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries from the Backhouse family and their heirs, the Lloyds. Sir Samuel Backhouse, one of the original New River 'Adventurers', owned the freehold of the property at and around New River Head when the 'river' was built in 1604–13. In the late 1630s disputes arose between the company and Sir Samuel's son, Sir John Backhouse, over the ownership of the ponds and the Water House at New River Head, the company claiming it had bought the freehold but lost the conveyance. Under the eventual settlement, the company bought the site of the Round Pond and the Water House outright, and that of the peripheral Waste Pond for a perpetual annuity.

The terms allowed the company to lay pipes across the surrounding fields, which were generally let for grazing. This it did, liberally. So things stood until the 1730s when the company became embroiled in dispute with the Rev. John Lloyd, heir to the Backhouse lands, who complained about the company's building works and damage to his fields from leaking pipes. Under an agreement of 1742 and a conveyance of 1744, the company undertook to pay Lloyd £525 and a perpetual annuity of £362 10s for over 55 acres, effectively acquiring the freehold (Ill. 239). This included the New Inn on St John Street Road near the Angel, and the Upper Pond built by the company in 1708 at what was later to become Claremont Square. (The New River bed itself was excluded, and continued to be held under a kind of way leave.) (fn. 5)

The New River Company's land, still let for cattle grazing, was managed from a farm at the New Inn. The last agricultural tenant, in the early nineteenth century, was Richard Laycock, a dairy farmer and a substantial entrepreneur who also occupied several hundred acres of grazing in Islington around 1810. In that year consideration was given to using the company's land near the Angel for a large cattle market to replace that at Smithfield. Nothing came of this, but more lucrative use of the land became ever more pressing as the company's commercial position weakened: the formation of four new London water companies since 1805 had brought a sharp reduction in revenues, and the perpetual payment to the Lloyds was an additional burden. Building was the obvious solution. Already the estate was becoming encircled by builtup areas, with the well-established suburb of Pentonville to the north and the streets of the Brewers' Company and Northampton estates to the east. (fn. 6)

Matters were complicated by the lines of pipes radiating across the fields from New River Head. It was a fortunate convergence in its affairs that, prompted by the imperatives of competition, the New River Company had begun to modernize this distribution network, replacing a multitude of elmwood pipes with higher-capacity cast-iron mains. Iron pipes had been tried out as early as 1790. Replacement was gradual until 1810, when expenditure was recognized as an urgent necessity. In full swing by 1813, the network was completed in 1819 as a wholly underground system, rationalized to prepare the way for building development. In anticipation Laycock's new lease of 45 acres in 1811 had included provision for the company to reclaim parts of the land at three months' notice. Having come through this commercially difficult period, the company moved its headquarters to the newly enlarged Water House in 1820. This was also the residence of William Chadwell Mylne, the company's surveyor from 1810 until 1861. From here he oversaw both the pipe-replacement programme and the development of the estate. (fn. 7)

Outline of building development, 1811–53

In the summer of 1811 the first steps were taken towards the building of the eastern part of the estate. Mylne was directed to prepare a plan for first-rate houses there, and he advised the Vestry of the company's intentions to build on its ground near Sadler's Wells. Laycock began using the western part of the estate for making bricks, and in the following year part of the Cistern or Water House Field was taken from him, for the commencement of the south side of Myddelton Street. Two years later a parish watchhouse was built opposite. Although no early plan of the proposed street layout appears to survive, it is clear that by the summer of 1815 the company was committed to the idea of building a large square, the future Myddelton Square. (fn. 8)

In that year a start was made on Myddelton Terrace, later to become the west side of Claremont Square. But the last years of the Napoleonic Wars had been a difficult time for builders and little else was done. By 1816 the company had taken about 15 acres from Laycock for building, but had agreements for only 44 houses, all in these two places. Most of this commitment was by Henry Hammond, a Holborn glass dealer, who was bankrupted in 1817, just as the building cycle was beginning to pick up. On the New Road (Pentonville Road), Claremont Terrace was begun in 1818, and Mylne's plans for the whole area from Amwell Street, an existing path, to St John Street were finally settled in 1819, the streets and squares all being laid out by 1820, ready to take names deriving from New River Company history. To the west, the hillside Hanging Field continued to be let to Laycock, who sublet small plots in the 1820s as allotments and pleasure grounds known as Myddelton Gardens. By 1821 John Scott, a Hoxton brick and tile merchant, had become the principal brickmaker on the company's land. (fn. 9)

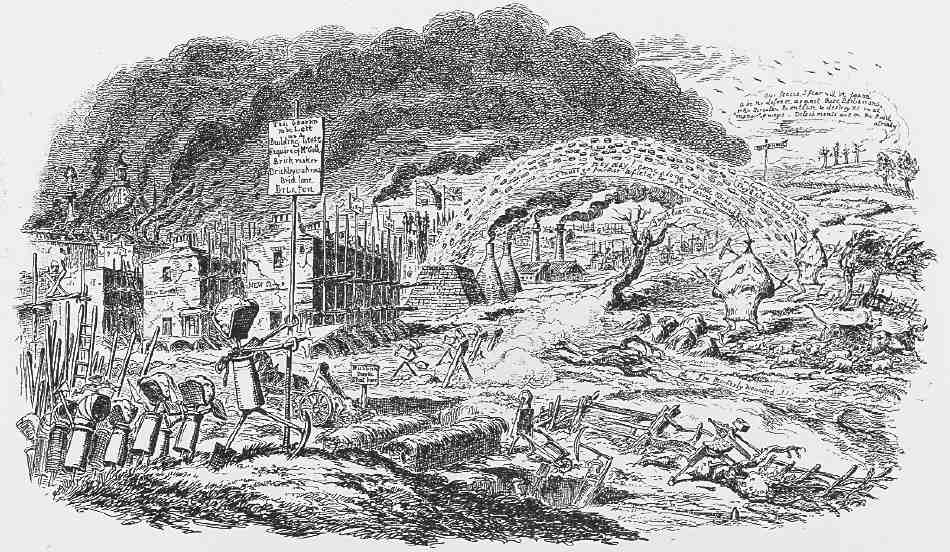

240. 'London Going Out of Town, or, the March of Bricks and Mortar', 1829. Drawn by George Cruikshank during his residence in Amwell Street

The start was slow, only 58 houses having been completed by 1821, but thereafter the pace was frantic, with 387 more houses finished by 1829, when George Cruikshank, a local resident, drew what is perhaps the best known evocation of London's early nineteenth-century expansion. (Ill. 240). The first building agreements for Amwell Street and Myddelton Square were made in 1822, those for the rest of Claremont Square in 1823. Edward Cowper Fyffe, a New Cavendish Street grocer, was one of the biggest entrepreneurs, agreeing to build 50 houses on and behind Amwell Street. He fell bankrupt in 1824, foreshadowing the general downturn a year later. Fyffe's commitment was efficiently taken over by the partnership of Edward Garland and Philip Perkins, who built 36 houses themselves, of which 35 survive. The biggest overall take was by James Stalley, who agreed to build 61 houses on and to the north of Myddelton Street in 1823–7, of which none survive. The completion of Claremont Square in 1828 was largely due to Richard Chapman, who undertook 35 houses on the estate. He had earlier built on the Penton and Northampton estates, and was also active on the Stonefield or Cloudesley estate in Islington. (fn. 10) St Mark's Church was built in the middle of Myddelton Square in 1825–7, but there were difficulties completing the surrounding houses as building activity slowed. The square was finished only in 1836, many builders having been involved; the largest contribution was that of the partnership of Thomas Priddle and William Manser, who built 18 houses. Only 45 houses were completed on the estate between 1830 and 1838, of which 23 were on Myddelton Square.

Faced with the slowdown, development westwards had been suspended. Mylne waited until late in 1836 before deciding that what was to become Great Percy Street should be made up, its line having long since been determined. Building agreements followed from 1838. There was new impetus towards completion of the estate, and plans for Percy Circus were settled in 1841, when Holford Square was also begun. Yet from 1839 to 1845 only 72 houses were built, nothing like the pace of the 1820s, and from 1846 until 1853 just 95 were added. There were further difficulties with bankrupt builders, not obviously the result of over-ambition, but more likely due to the declining marketability of the area. Francis Sandon came close to financial ruin in 1841, and John Lowther and Thomas Gates James were both bankrupted, in 1842 and 1843, respectively. Their commitments, seven to ten houses each, were relatively small. In 1844 Mylne had yet to seal agreements for the last 55 intended houses. The financial crisis of April 1847 evidently accounted for William Watkins, who had built 25 houses on the estate and who was heavily committed at Holford Square. This bankruptcy pushed his backer, James Rhodes, into taking on all 27 outstanding building plots on the estate to protect his investment. Rhodes had strong local roots as the son of Samuel Rhodes, a major Islington and Hackney landowner, brickmaker and developer. He was also building in Islington from the 1830s to the 1850s. (fn. 11) In all Rhodes undertook 55 houses on the New River estate, seeing to the completion of Holford Square in 1848 and Percy Circus in 1853.

Rhodes's work brought to a close the main development of the estate, but further building ground became available in 1857 with the closure of the company's reservoir south of Sadler's Wells. This was built over with houses by 1862, through the developer Henry Rydon.

Building control and the builders

Control of the building process was in the hands of W. C. Mylne for a remarkably long time, a crucial factor in the estate's sustained coherence and stylistic conservatism. As estate surveyor for 50 years he oversaw the terms of building agreements, and the issue of leases was subject to his giving approval (from 1820 he insisted on seeing the district surveyor's certificates before he would do so). Unlike other local landowners, the company was strict about withholding leases until buildings had been completed, though, as in any well-managed development, there were occasional instances of flexibility to help builders through hard times. Mylne dictated architectural form and ensured quality and uniformity, exercising notably tight control, specifying building materials and methods down to the constructional details of guttering and cellar partitions. (fn. 12) Through him the siting of shops and public houses was carefully managed, and he designed the large new church for the estate's biggest square, an essential component of the project.

The initial aspiration towards first-rate houses was unrealistic, but good standards were maintained. The houses were generally specified so as to be at the 'full sized' or upper end of the third rate, which meant frontages of about 17 ft and house depths of about 27 ft. Others, particularly in the squares, were second rate. Mylne kept a steady hand on the tiller through the 1820s, but on Great Percy Street in the early 1840s there was vacillation over what size of house would sell. Fourth-rate houses were avoided except in a few places intended to include shops and to house tradespeople; Arlington Way and Upper Rosoman Street were expressly given 'full sized' fourthrate houses with 15 ft frontages.

The first leases of c. 1815 ran for 90 or 91 years, the terms of later leases gradually diminishing to about 75 years by the 1840s, so as to ensure that all would fall in more or less together. This broke down only in 1847 when James Rhodes was able to secure terms of 85 years.

The speculators and builders with whom Mylne dealt came from a wide range of building-trade and other backgrounds. Many of the early entrepreneurs may have known each other prior to their involvement on the estate, and perhaps worked more collaboratively than documents disclose. Early work on Myddelton Terrace in 1815 was taken on by Thomas Richard Read, a Gray's Inn Road glass merchant, Robert and George Cooke, Fleet Street glaziers and painters, and Henry Hammond, the Holborn window-glass maker and dealer. These and men from other building trades appear to have built Myddelton Terrace through work-for-work or cross-contracting arrangements. Edward Cowper Fyffe, the New Cavendish Street grocer, became heavily involved in 1822. He was the partner of Henry Minter Fyffe, a Holborn grocer and tea dealer, who had been involved in the rebuilding of the Angel Inn. Another Holborn tradesman, William Harris, optician and optical instrument maker, was to take on eighteen houses from 1823. Others who entered the field as speculators included some New River Company employees, most notably Richard Saywell, collector for Covent Garden and Fleet Street, who, over time, built nine houses on the estate.

A number of local men who had been associated with house-building elsewhere in Clerkenwell moved on to speculations here, among them the glass-merchant Read and Richard Carpenter, who teamed up to develop Arlington Way in 1822–4. Carpenter and his brother Thomas were watch-case makers, their father's trade, with premises in Islington Road (now the northern half of St John Street), and were also in business as cattlemen. Thomas Carpenter and Read were both concerned in 1804–10 with some development in and around Northampton Square (see Survey of London, volume xlvi), and Read was in at the start of building on the New River estate, at Myddelton Terrace and Claremont Terrace, where he lived in one of the houses he had built. After developing Arlington Way, Richard Carpenter moved into a new house in Myddelton Square. He went on to develop Lonsdale Square in Islington in 1838–42 with his son, the architect R. C. Carpenter, during which time he also became district surveyor for Clerkenwell, a Clerkenwell Improvement Commissioner and Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex. He was a commissioner of sewers for Holborn and Finsbury from 1811. Carpenter junior contributed significantly to later development on the New River estate, and was himself architect to the Improvement Commission and district surveyor for East Islington from 1853 until his death in 1855. He too was a local commissioner of sewers, from 1834. (fn. 13)

Other important developers on the estate, like Richard Chapman or Thomas Oliver, appear to have been builders and nothing else. Through the whole development 35 different people each agreed to build five or more houses, and many others undertook fewer. The largest take, James Stalley's 61 houses, represents only 9 per cent of all the houses built. There was, therefore, no single dominant developer, at least not before 1847 when responsibility for completion of the estate was handed to Rhodes.

Despite Mylne's rigorous control of the building process, in principle at least, there were numerous difficulties, which forced compromise and some loss of uniformity. His first builder, Abraham Richardson, failed to come up to scratch in 1812–14. Richardson's successor, Hammond, sub-assigned the building of houses, and though these were completed in 1816 he failed to exercise supervision and they were not constructed in accord with the building agreements. As he confessed, once bankrupt in 1817, he had not even visited the estate for a year. William Harris sub-assigned to John Ramsay, a tailor, who was responsible for building twenty-two houses over a lengthy period. In 1825 Ramsay was found to have evaded the signing of agreements, and in 1829 Mylne reported, with obvious exasperation, 'this person has never built a good house on the Estate'. (fn. 14) In what had become a flat market in the early 1830s Mylne had great difficulty pushing various builders to complete Myddelton Square, threatening James Armsby with a law suit in 1831.

One consequence of this fragmentary development by numerous small builder-entrepreneurs was the fact that several of the builders put up houses for themselves, typically ensuring that their own buildings were larger or more lavishly appointed than others. This is the explanation for some of the more visibly egregious departures from Mylne's standards. John Scott, the brickmaker, built himself what is now No. 16 Claremont Square in 1821–3, making it wider and taller than its neighbours. He built elsewhere on the estate up to 1830 and became 'one of the most opulent and respectable men in the parish', (fn. 15) but in 1834 he was on the run having over fourteen years embezzled some £10,000 from parish funds. (fn. 16) In 1823–5 Thomas Oliver, who built eleven houses on the estate, gave himself the tallest house and biggest garden on Amwell Street, at No. 76. He was perhaps related to William Oliver, both men having arrived on the scene in 1822. The latter, a timber merchant who built a showroom-warehouse for mahogany in Sekforde Street in 1828 (see Survey of London, volume xlvi), undertook 32 houses on the estate, including some of the biggest and best finished, taking first No. 65 Claremont Terrace and then the doublefronted No. 42 Claremont Square for himself.

The architecture of the New River estate

The overall appearance and general character of the estate is due above all to Mylne, whose role in the design and planning was primary. Mylne was essentially a water engineer, and his architectural achievements beyond this estate are few. Yet he was the son of a highly competent architect-engineer, and was evidently wholly conversant with the vocabulary of late Georgian estate development in London, as it had become standardized and codified in the decades up to 1810. The blank canvas of the New River Company's fields allowed him to devise an orderly layout with three squares, one of which linked to a circus. The result has long been admired for the clarity, rationality and geometry of its townscape and planning. (fn. 17) Into this framework Mylne introduced a number of prospects: the view up Inglebert Street to St Mark's Church (Ill. 271); the view up Garnault Place to his own home in the Water House at New River Head, conceived as a mirroring of the Tysoe Street view to Wilmington Square from a small 'circus' at the London Spa junction; and the widening of Amwell Street that allows it to be seen to process up to Claremont Square (Ill. 253). The integrity of Amwell Street is one of several instances of close collaboration with the Lloyd Baker estate, another indicator of Mylne's effectiveness as a surveyor.

At the level of individual houses Mylne provided a template for highly standardized surveyor's architecture, appreciated by Christopher Hussey in the 1930s through a repetition of Steen Eiler Rasmussen's evocation of London's Georgian houses as a 'refined industrial product'. Mylne defined the design parameters, and inventions by builders were, for the most part, constrained to keep within the regularity of what amounts to a 'house style'. This is made up of stock forms and details, and has local precedents and parallels, as nearby at Northampton Square or in Islington on the Cloudesley estate of the 1820s.

Adherence to straightforward terrace form seems to have been broken only for a flirtation with semi-detached villas on Hardwick Street in 1822, perhaps inspired by W. J. Booth's inventions on the Lloyd Baker estate. What were already conservative stylistic forms endured well into the 1830s, helping to ensure unity. In Mylne's hands a shift to a more fashionably Italianate approach was tentative, even in the 1840s. However, it should be borne in mind that perceptions of the estate as being 'Georgian' are coloured not just by its conservative architectural character, but also by the fact that of the 95 houses built on it from 1846 to 1853 only thirteen survive, largely an accident of war damage. The still later houses in and around Rydon Crescent have also almost all been destroyed, by bombing or for public housing redevelopment.

Others made scarcely any design contribution in the houses built in the 1820s. Henry Garling, himself an architect, built a house on Claremont Square that shows no outward sign of difference. Taking into account the difficulties that Mylne had to cope with in managing this project, and the fact that he was approaching 60 when development picked up again in 1838, it is perhaps not surprising that, after that point, he appears to have disengaged somewhat. The elevations of Percy Circus and Holford Square were probably not by him, but by other, younger, architects. Richard Cromwell Carpenter had local roots. As a boy he lived at No. 62 Myddelton Square with his father, who had developed Arlington Way (Ills 274, 275), and he began his working life hereabouts with John Blyth in 1826. He emerged as an architect and speculator in his own right on this estate in 1839, when he was responsible for the design of the Percy Arms public house (Ills 287, 288). He was probably also the author of the carefully modulated elevations of Percy Circus, designed in 1841 (Ills 291–4). James Harrison, who took on some small speculations in the early 1840s, may have been involved with the design of Holford Square (Ills 298, 299).

The typical three- or four-storey terrace on the New River estate has first-floor blind arcading, introduced in Myddelton Terrace and consistently redeployed in the developments of the 1820s north of New River Head (Ills 246–8, 250–2, 255, 260–2). Faced with the strong impression of uniformity that the estate generates, it is surprising to realize the degree to which, beyond this, elevational conformity was not attained. The piecemeal nature of the execution goes far beyond the oddities of builders flattering themselves with big houses, and is expressed through almost endless variation in details. It is clear that irregularity vexed Mylne, but it is the variety of detail that is the source of much of the area's enduring charm. This can be seen through the presence or absence of rusticated stucco on the lower storeys; in shifts back and forth between round or square heads to ground-floor windows; in the impost bands of the first-floor arcading, whether present, absent, or embellished; in the entrance surrounds, of which there are many types; or in fanlights, of which a wide range of semi-circular examples survive (Ills 252, 255, 264 and 284). (fn. 18) The arrival of Italianate detail after 1838 was entirely typical, with stucco architraves the usual minimum (Ills 287, 291–4, 298, 299). There was much conservative repair and replacement around 1910, with many door architraves, balconies and sash windows echoing but not quite replicating earlier forms. From then into the 1970s the New River Company kept a uniform and distinctive painted livery, with brown lower storeys and cream mouldings and reveals (Ill. 250).

Behind their fronts New River estate houses almost invariably have the two-room rear-staircase plan that had become the all-but universal standard in London by 1800 (Ills 245, 249, 263, 274, 289 and 295). Most of the few exceptions are end-of-terrace houses that have essentially the same plan, but with side entrances that avoid the wasted space of a long entrance hall. The two groundfloor rooms were generally linked, folding double doors allowing them to be made a single large space. Another general and state-of-the-art feature, unsurprising given the business of the freeholder, was the provision of water closets, often two per house, in small rear service wings. Interior finishes appear to have been highly conformable, with stick-baluster staircases and simple fireplaces, architraves and ceiling cornices typical of the period, though much has been remade.

Most of the new housing on the estate in the twentieth-century, both infill and replacement, was designed for the New River Company under C. S. Sanders, with Lewis Solomon & Son, architects, heavily involved by the 1930s, diversifying from earlier responsibility for commercial premises. A surprisingly suburban note is struck by the Edwardian maisonette flats on Cruikshank Street. The later and larger blocks of flats in neo-Georgian idioms stand out less, except perhaps in the even more suburban grouping of Claremont Close. After the war there were tentative moves towards Scandinavian design models, and then a short-lived shift in another direction on Arlington Way with the adoption of system building in 1958. Limited late twentieth-century rebuilding has been generally conservative in character, following the exigencies of conservation area and listed building legislation. Visual coherence and sober regularity have been sustained in what is now widely recognized as a distinctive and valuable exemplar of early nineteenth-century planning and townscape.