Pages xxxix-lvii

An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 5, Central. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1981.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

Ecclesiastical Architecture

Parish Churches

Before the Reformation there were twenty-three parish churches in the central area of which fourteen survive in whole or in part. Only six of these are now in regular use. Redundancy is not a modern problem: four intramural churches were demolished in the 14th century and a further seven in the 16th century, while St. Andrew's survived only to be converted to secular use. St. George, Fishergate, was ruinous by the 18th century. Holy Trinity, King's Square, survived a threat to its existence in 1824 and, after twice suffering truncation for road widening, was largely rebuilt in 1861 and finally demolished in 1937. In 1885 most of St. Crux was pulled down; it is now represented by a Parish Room incorporating some of the original masonry and containing some original fittings. After the bombing of St. Martin, Coney Street, in 1942, little more than the tower and S. aisle was reinstated as a roofed structure. As this area of York was so well provided with churches none of the three friary churches was adopted for parochial use; the church of St. Leonard's Hospital was demolished and its infirmary chapel left in ruins. Of the chapels connected with the various guilds, only that attached to the Merchant Adventurers' Hall has survived as a chapel.

With the dissolution of chantries, St. Anne's Chapel on Foss Bridge became a store; eventually its stone was used for repairing Ouse Bridge after damage by floods in 1564. The chapels connected with the religious guilds were suppressed: St. Christopher's Chapel, at the entrance to the Guildhall, became the Cross Keys Tavern, and gave way to the Mansion House in 1726. The position of the former chapel in St. William's College is now uncertain. The survival of the Vicars Choral as a collegiate body after 1552 led to the retention of the Bedern Chapel, now a roofless shell.

Very little is known about the early churches in the central area of York. A 10th-century origin has been postulated for the first phase of St. Helen-on-the-Walls, recovered by excavations (P. V. Addyman (ed.), Excavations in York 1973–1974, Second Interim Report (1976), 20–22), and a number of carved stone fragments found in or near St. Denys', All Saints, Pavement, St. Sampson's and St. Crux, and burials at St. Saviour's suggest that there were pre-Conquest churches on these sites. However, the only standing remains certainly of pre-Conquest date are at St. Mary, Castlegate; they are insufficient to give information about the original shape of the church other than the width of the nave. The remarkable dedication stone, preserved in the church, is of the early 11th century but the date is unfortunately missing. Part of the E. wall of St. Cuthbert's may be of the early 11th century. Other pre-Conquest fragments may be associated with the former church of St. Leonard, which later gave its name to St. Leonard's Hospital, and with the former chapel of St. Martin-on-the-Hill; a burial ground in the Parliament Street area may have belonged to a church dedicated to St. Swithin. In addition, Saxon burials in the Petergate area give supporting evidence for a pre-Conquest origin for St. Michael-le-Belfrey.

Evidence for the existence of a number of elaborately-decorated Norman churches is provided by sculptured fragments, mainly in the form of corbels or parts of archways, including two notable reset 12th-century doorways, one at St. Denys' and the other at St. Margaret's, the latter brought from the extramural church of St. Nicholas. Remains of other elaborate 12th-century doorways probably from All Saints, Pavement, and St. Wilfrid's are in the Yorkshire Museum (York IV, Plate 28). One surviving voussoir at St. Martin, Coney Street, carved with a dragon enclosed in a roundel (Plate 28), is similar to others on the archways from All Saints, Pavement, and St. Nicholas'. Standing structural remains of the period are few. Fragmentary remains at St. Martin, Coney Street, indicate a late 11th-century church consisting of a single cell, and early 12th-century churches with this simple plan probably existed at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, and St. Helen, Stonegate. Structural chancels were added to all these churches in the course of the 12th century, and probably also at St. Mary, Castlegate, St. Helen-on-the-Walls (Addyman, op. cit.), St. Mary-ad-Valvas (excavated in 1968) and St. Sampson's (YPSR for 1974, 28). St. Michael, Spurriergate, however, was built in the 12th century with aisles but without a structurally separate chancel, St. Denys' had a central tower between the nave and chancel, and the discovery of the foundations of a 12th-century transept at All Saints, Pavement, must indicate a cruciform church of that date.

Alteration and rebuilding of York churches have been such as to make the architectural development of some of them problematical. Enlargement was usually by the addition of aisles or of side chapels subsequently extended into aisles. These enlargements were probably often undertaken to accommodate chantry foundations, whose existence is well documented. The large N.E. chapel of St. Martin's was early added as a chancel to the 11th-century church, but a similar explanation does not fit St. Denys' where the origin of the large N.E. chapel, apparently rebuilt in the 14th century, remains obscure. Whatever the earlier shape, nearly every church was converted in the late 14th or the 15th century to a plain rectangular plan with no structural division between nave and chancel. It might be aisleless, as at St. Cuthbert's, or with one aisle, as at St. Margaret's, but the most usual plan had N. and S. aisles extending the full length of the church. This last was the plan used when St. Michael-le-Belfrey was completely rebuilt in the 16th century. At St. Denys' there was a central tower, but elsewhere towers were built at the W. end. St. Mary's tower is surmounted by a spire, similar to that at All Saints, North Street (York III, Plate 11); there was formerly a stone spire at St. Denys', taken down in 1798, and a spire of timber covered with lead at Holy Trinity, King's Square. The tower of All Saints, Pavement, is surmounted by a fine octagonal openwork lantern but the smaller octagonal lanterns at St. Helen's and St. Michael-le-Belfrey, not supported by towers, are both of 19th-century design in their present form.

Architecturally the churches are generally rather plain. St. Michael, Spurriergate, has good clustered columns with water-leaf capitals but other churches have plain octagonal piers with simple moulded capitals or with arches dying directly into the piers, a form which is only elaborated by ingenious intersections of arch chamfers with each other and with the octagonal piers below, as in the towers of St. Martin, Coney Street, Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, and All Saints, Pavement. The church of St. Crux, rebuilt in the 15th century, seems to have been more richly treated; the tower of St. Michael, Spurriergate, also of the 15th century, exhibits remarkable water-leaf capitals in imitation of those of the arcades of three centuries earlier; but only in the 15th-century work surviving at St. Martin, Coney Street, and in the 16th-century St. Michael-le-Belfrey is there any real sense of architectural richness surviving. Both these churches exhibit the typically Yorkshire feature of buttresses surmounted by pinnacles joined to the wall by little flying buttresses. The pierced parapets at St. Martin's are a 19th-century reconstruction of a mediaeval feature.

The building of new churches came to an end after the completion of St. Michael-le-Belfrey and in 1548 the abolition of fifteen decayed churches was proposed. St. Helen, Stonegate, was one of these and demolition had already started when a decision was made in 1554 to restore the church. Seventeen decayed parishes were finally united with twelve others in 1586.

The siege of York in 1644 caused less damage to churches in the city than in the suburbs; but the tower and body of St. Denys' and the tower of St. Sampson's were damaged. Later in the 17th century the tower of St. Margaret's collapsed and was rebuilt, and at the end of the century a tower was added to St. Crux in a classical idiom. All Saints, Pavement, lost its chancel and the flanking aisles in 1782 to make more space for the market. In 1797 the W. wall of St. Denys' collapsed and the whole nave was removed. St. Michael, Spurriergate, was curtailed on the S. and E. sides in 1821–2 for street widening. Restoration in the 19th century was drastic and at St. Saviour's and St. Sampson's involved complete rebuilding of all except the W. towers. St. Denys' was remodelled in 1846, when the central tower was pulled down and a new tower built further W. Partial rebuilding of St. Margaret's followed in 1851 and a new chancel was added to St. Helen's in 1857. Other late changes included the rebuilding of the W. end of St. Michael-le-Belfrey in 1867 after adjoining houses had been cleared away, and the rebuilding of the W. end of St. Helen's in 1875–6. Clerestoreys now remain only at All Saints, Pavement, St. Michael-le-Belfrey, and St. Mary, Castlegate, which has a low clerestorey with only two windows each side, but formerly existed also at St. Crux, St. Martin, Coney Street, and St. Michael, Spurriergate.

Almost everywhere the internal arrangement of the churches was drastically altered by the Victorian restorers. In St. Michael-le-Belfrey and St. Michael, Spurriergate, the early 18th-century sanctuary fittings remain more or less in their original condition, but only Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, is relatively undisturbed by 19th-century rearrangements: not only do the early 18th-century altar rails remain with their curved gates, typical of York, but the body of the church still retains its 18th-century box-pews. New pews made for St. Saviour's in 1845 were said to have been modelled on their 17th-century predecessors, but they no longer exist. In some churches the earlier arrangement of the interior can be seen on the large-scale OS map of 1852.

Roofs. The roofs are mostly very low-pitched and none is earlier than the 15th century. The low pitch facilitated an internal treatment of rectangular compartments formed by moulded beams, generally with bosses at the intersections carved, except at St. Michael-le-Belfrey, with heraldic or foliated designs. At Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, only the Chapel of St. James has a low-pitched roof, but the same appearance is preserved in the nave and aisles where flat ceilings supported by moulded beams conceal the high-pitched roofs. An exception to this treatment associated with another high-pitched roof is at St. Cuthbert's, where arch-braces rise to the main members of a pointed wagon roof, with false hammer-beams to alternate trusses.

(I.R.P.)

Friaries

Apart from a house of the Friars of the Sack which had only a brief existence, there were four friaries in York, all founded in the 13th century and situated within the walled city, though the Carmelite Friary was initially outside the walls in the Horsefair (York IV, xxxvii). Each of the houses in the central area had a river frontage. The Augustinian Friary (21), on the S.W. side of Lendal, had a gateway to the street and a frontage to the Ouse. The Carmelite Friary (22), near Fossgate, is known to have had a gateway to that street and had a quay on the River Foss. The Franciscan Friary (23) had a site extending from Castlegate, where there was a gatehouse, to the Ouse, and the boundary on the S.E. extended to the city wall (York II, 158). This friary, standing near the castle, was favoured for use as a residence by Kings Edward I, II and III, when visiting York. The surviving remains of these three friaries consist of little more than a few lengths of precinct wall; the walls facing the Ouse of both the Augustinian and Franciscan friaries have indications of water-gates. The fourth friary, of the Dominicans, was outside the central area on Toft Green, S.W. of the Ouse, on a site now occupied by the old Railway Station (York III, 53). There are no surviving remains.

Though virtually nothing is known of the churches or conventual buildings of the friaries, it may be noted that the parish churches of St. Mary, Castlegate (11), close to the Franciscan house, and All Saints, North Street (York III, (4) 3), in the vicinity of the Dominican Friary, both have spires rising from octagonal drums. This was a feature favoured by the friars, as illustrated by the fine surviving example at the Grey-friars, Coventry; it is possible that these two parish churches reflect such predilection.

(D.W.B.)

Nonconformist Chapels

Many of the Nonconformist buildings in the area have been demolished or converted to other uses; their history appears in the Victoria County History, The City of York, 404–18, and need not be repeated here. The earliest surviving chapel is the unusual cruciform brick building in St. Saviourgate, built in 1692 as a Presbyterian chapel but becoming Unitarian in the 18th century (Plate 66). The only earlier meeting house was an adaptation by the Society of Friends of a house in Friargate, acquired in 1674 and altered four years later.

The Centenary Chapel, designed by James Simpson of Leeds in 1839, is distinguished by its stone Ionic portico (Plate 66). The Salem Chapel of the same date, now demolished, had a lofty columnar porch (Plate 66). It was designed by J. P. Pritchett, who was also responsible for the Lendal Chapel and the Friends' Meeting House.

Roman Catholic Churches

A house in Little Blake Street, now Duncombe Place, probably served as a home for Roman Catholic priests from about 1688, and part of it was opened for public worship in 1760. A new chapel, dedicated to St. Wilfrid, was opened on the opposite side of the street in 1802 and a view in York City Art Gallery shows that it differed little in appearance from contemporary Nonconformist chapels. When Duncombe Place was built in 1864 a new church of St. Wilfrid, designed by George Goldie, was built in French Gothic style. The Roman Catholic church of St. George of 1850, provided for the growing population in the Walmgate area, is English Gothic in style and in marked contrast to the Nonconformist chapels, which continued to be built in a basically classical style. Joseph Hansom, who with his brother Charles designed the church, became an outstanding architect of Roman Catholic churches in the second half of the century.

Churchyards and Burial Grounds

One early mediaeval burial ground (16), now obliterated by later building development, was probably connected with a long-vanished pre-Conquest church the dedication of which is suggested by the former St. Swithin's Lane. All the parish churches probably had adjacent churchyards. Several of these were reduced in area by the erection of buildings, the rents from which supported chantries, notably at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, St. Martin, Coney Street, St. Michael, Spurriergate, and St. Sampson's. The enlargement of the churches further reduced the area available for burials. After the suppression of the chantries, the process of reduction continued, usually in the interests of road widening. At its most extreme, so much ground was lost that detached burial grounds had to be created. St. Michael-le-Belfrey possessed an extramural burial ground outside Monk Bar. Saxon burials found to the S. of the church, under Peter-gate, suggest that the loss of ground to roadworks has a long history. St. Helen's had a new burial ground (20) created in Davygate to compensate for the loss of land to St. Helen's Square. St. Crux, which lost land to Pavement on the S. and more land to properties in the Shambles on the N., acquired a detached burial ground (18) to the S. of St. Saviour's, entered from Hungate. Inscribed stones have survived in two former churchyards after the demolition of their respective churches: in King's Square (17) associated with the church of Holy Trinity, demolished in 1937, and a number of late headstones in the former St. George's churchyard (19).

Church Fittings

Altars. The most impressive survival is a large dark marble slab in the floor of the nave at St. Michael-le-Belfrey, said to have formerly shown consecration crosses. Johnston, writing on 19 March 1669, described it as 'a Marble stone in the middle Isle 5 Yards and 2 Inches long which they say was the Altar stone in the Minster ... [it] was brought hether in anno 1617' (Bodleian, MS. Top. Yorks. C14, f. 174). Only one slab still serves its original purpose: a mediaeval slab with consecration crosses has been reused in the Chapel of St. James at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate. There is another complete slab and a fragment, both with consecration crosses, in the same church.

Bells. The chequered history of York's churches is reflected in the fate of the bells cast for them, mainly by York bell-founders. Many have vanished with their churches, and others have been rehung in other churches in York, or further afield. Industrial pollution and neglect have resulted in corrosion, so that the inscriptions on several of the surviving bells are difficult to decipher even with the aid of transcripts made when deterioration was less advanced. The central area of York still retains a good representative series of bells from different centuries. The history of bell-founding in York was studied by G. Benson (The Bells of the Ancient Churches of York (1885); 'York Bellfounders', YPSR (1898); AASRP, xxvii Pt. 2 (1904)).

The earliest surviving bells in the central area are probably of 15th-century date. One, at St. Michael, Spurriergate, was brought with four other bells from the Minster in 1765. In common with most mediaeval bells there is no date but it may be one of a set of three made in 1466 or four made in 1475. The inscription has each letter made from a separate stamp, with the capitals surmounted by a crown. Three 15th-century bells survived at Holy Trinity, King's Square, until its demolition and are now at Hazlewood Castle, North Yorkshire. The inscriptions were recorded by Benson, who attributed the bells to Henry Jurdan of London. Other late mediaeval bells are at All Saints, Pavement, Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, and at St. Sampson's, where one has the initials RB, possibly for Richard Blakey (free 1501). There was a Flemish bell dated 1523 at St. Crux, now rehung at Bishopthorpe church. One late 16th-century treble bell at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, inscribed 'Repent Least ye Perish', is probably by Robert Quarnbie and Henry Oldfield I, active in Nottingham in 1570–93 and 1539–89 respectively (ex inf. R. W. M. Clouston).

Bell-founding languished after the suppression of many churches in the 16th century, until William Oldfield reintroduced bell-founding to York c. 1620. He was succeeded by Abraham Smith and William Curedon, who cast bells in York until 1663. They ran the joint business of bell-founders and braziers, and cast bells on Toft Green. The Smith dynasty continued with Samuel Smith senior, who worked from 1662 until 1709, and his son Samuel Smith junior, who died in 1731, bequeathing the bell-house on Toft Green to his brother James, who seems to have disposed of the business. This was probably because of competition from the Seller family, with its bell-house in Jubbergate. The founder of the business, William Seller, cast most of his bells for Lincolnshire, and the York market was probably only broken into by his son Edward (Sheriff in 1703–4, died 1724), whose earliest dated York bell is 1718. His son, Edward Seller II (Sheriff in 1731–2) dominated York bell-founding until his death in 1764, when the business was disposed of. This facilitated the rise of a third family with George Dalton, brazier and bell-founder, who moved in 1764 from Stonegate to Lendal where 'he had a commodious foundry and good water carriage'. His sons, Robert and Henry, were also in the business, but bell-founding ceased in York at the beginning of the 19th century.

William Oldfield, whose mark from c. 1614 was a shield charged with a cross between the letters W O and two bells, has several bells attributed to him although the mark is often illegible or missing: one of 1621 at St. Denys', one of 1626 at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, two at St. Helen's, of which one is dated 1628, one of 1633 at All Saints, Pavement, and one of 1635 at St. Michael-le-Belfrey, which was recast in 1883. His favourite inscriptions, noted in York III, again occur: 'Jesvs be ovr Speed' (Holy Trinity, Goodramgate) and 'Soli Deo Gloria' (St. Michael-le-Belfrey). Benson attributed a further bell in St. Denys' to Oldfield in 1898, reading the date as 1631, but reattributed it to William Curedon in 1904 on re-reading the date as 1658. This is probably correct, although the inscription is now even more corroded.

Samuel Smith senior and Samuel Smith junior both used the same mark, SS/Ebor. The inscription 'Gloria in altissimis Deo' was used by Samuel Smith senior in 1673 at St. Cuthbert's, in 1682 at St. Mary, Castlegate, and in 1700 at St. Margaret's. His greatest achievement was four bells cast for the Minster, all of which bear the date 1681 and which are now in St. Michael, Spurriergate. He cast two pairs of bells bearing the same inscription and date: 'Jubilate Domino Psal. lxvi. 1681' occurs both on one of the bells for the Minster and on the treble bell from Holy Trinity, King's Square; 'Te Deum Laudamus 1693' occurs on a second bell from Holy Trinity, King's Square, and at St. Cuthbert's. Other bells by Samuel Smith senior were made for St. Crux in 1673, now at Bishopthorpe, and a second bell in 1700 for St. Margaret's. Samuel Smith junior was less prolific; for his bells see York II, 82, and York III, 15a.

Like the Smiths, both Edward Seller senior and Edward Seller junior used the same mark, E Seller/Ebor. Inscriptions used by the Smiths were also used by the Sellers: the favourite 'Gloria in altissimis Deo' was used in 1718 at St. Denys' and in 1729 at St. Martin, Coney Street, and 'Venite exvltemvs Domino', used by Samuel Smith senior at St. Margaret's in 1700, is used on a bell by Edward Seller senior at St. Maurice's in 1710. As well as casting the bell of 1718 at St. Denys', he recast a bell at St. Mary, Castlegate, in 1718. Edward Seller junior's major work was at St. Martin, Coney Street. Here he cast five of a peal of eight in 1729, and three more in 1730. All of these, except the tenor, were stolen c. 1960.

A sixth bell in St. Michael, Spurriergate, cast in 1765 to complete the peal acquired from the Minster that year, is probably by George Dalton. A plain bell, 12 in. diameter, from the Bedern Chapel, dated 1782, is now in the Minster stonemasons' store.

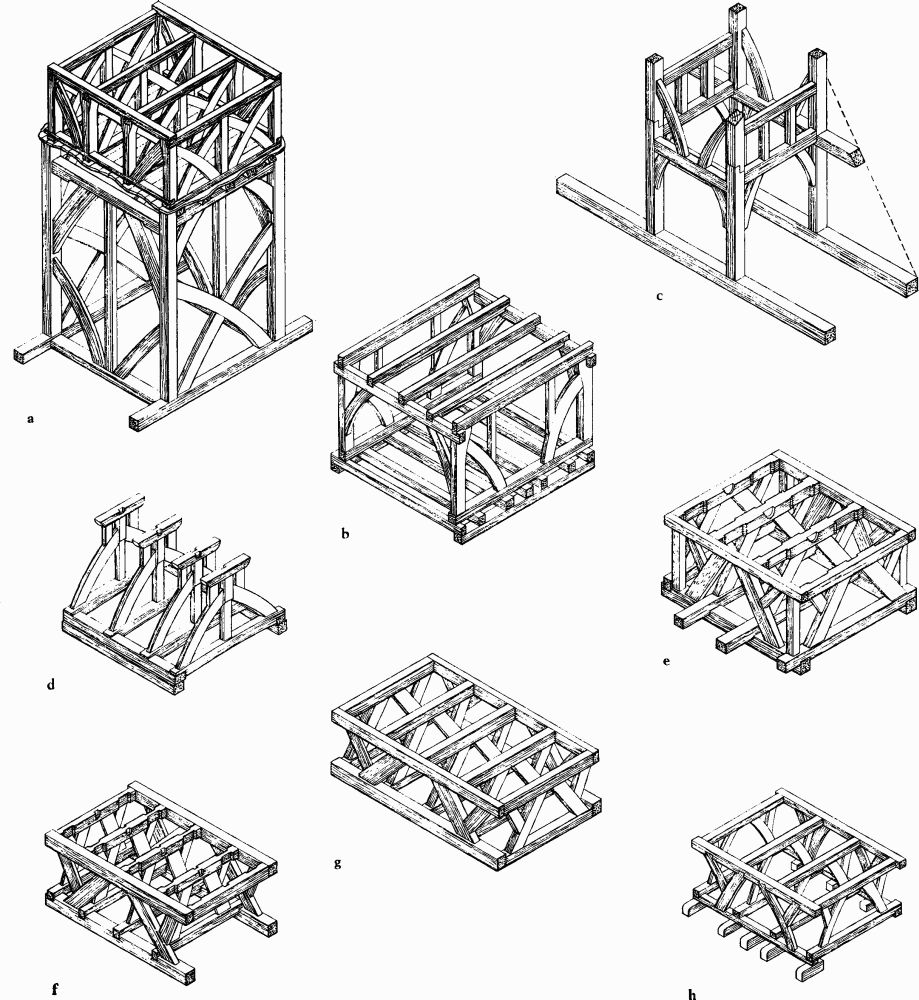

Fig. 1. Bell-frames.

a. (11) St. Mary, Castlegate. 15th-century.

b. (2) Holy Trinity, Goodramgate. Late 15th-century.

c. (3) St. Andrew's Hall. 15th-century.

d. (15) St. Saviour. Probably 16th-century.

e. (1) All Saints, Pavement. 1634.

f. St. John the Evangelist, Micklegate. 1646.

g. St. Martin-cum-Gregory. 1681.

h. (9) St. Margaret. 18th-century.

Bell-frames. Two 15th-century towers retain their original bell-frames, at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, and St. Mary, Castlegate. Both use contemporary timber-framing techniques, in particular, posts with enlarged heads and curved braces (Fig. 1). St. Mary, Castlegate, has the more elaborate frame, with a substantial sub-frame supporting it. An analogous structure is the bell-turret visible at the W. end of the nave in St. Andrew's. The frame at St. Saviour's is unique but may be compared with the framing of the belfry at Deddinghurst, Essex (C. A. Hewett, 'The Timber Belfries of Essex; their Significance in the Development of English Carpentry' in Arch. J., cxix (1962), Plate XXX). The arrangement, with three pits, may have been designed for the three bells acquired from St. William's Chapel in 1583 but never hung. The frame at St. Sampson's, which contains one bell possibly of the early 16th century, has been modified on numerous occasions. There are substantial posts at the mid-point of each principal face, with diagonal braces, which are probably early; subsidiary braces from the main braces to the top rail, for which evidence survives on the S. elevation, and posts inset slightly from each corner mark the transition to the most common 17th-century type. The bell-frame at All Saints, Pavement, was probably made in 1634 for the two existing 15th-century bells and a new bell dated 1633. Special permission was needed for 'strangers workemen', as the carpenters came from outside York. Apart from four posts, slightly inset from the corners, the frame is treated as a triangulated box with diagonal timbers between bottom and top rails supporting subsidiary diagonals to the top rail, and no posts in the plane of any of the four main frames separating the bells. The introduction of wheels to permit the bells to swing a complete circle resulted in the reduction in cross-section of the top rails where the bell rims might strike the frame. This feature was copied a few years later S.W. of the Ouse in the 1646 bell-frame at St. John's. Here all posts have been eliminated, a feature of the ultimate development seen also S.W. of the Ouse at St. Martin-cum-Gregory in 1681 (York III, Plate 21), where the spacing of the bell-pits was increased in order not to weaken the top rails. A late example is in St. Margaret's, where the tower of 1684–5 contains two bells of 1700.

Benefactors' Tables. The simplest type is a rectangular board of planks with a moulded frame. The most elaborate table was at St. Martin, Coney Street, which had enriched mouldings and a scrolled broken pedimental top (Morrell, Woodwork, Fig. 207). Exceptionally, benefactions are commemorated on marble tablets in three churches: in St. Margaret's a monument to Thomas Wilson, 1780, his wife Dorothy, 1786, and Dinah Richardson, 1788, also enumerates Dinah Richardson's benefactions; the monument to Dorothy Wilson, 1717, in St. Denys' is largely concerned with the terms of her will; in St. Sampson's a tablet dated 1818 records benefactions by Alice Green, but it is not a conventional memorial to her.

Relettering makes it difficult to date any specific table which may have later copying of an original list, and it is unwise to base a date purely on dated benefactions.

Brasses and Indents. For a city of the importance of York, the surviving mediaeval brasses are disappointing. Until the recent discovery of large indents at St. Saviour's and St. Mary, Castlegate, the only evidence in York for pre-Reformation figure brasses seemed limited to a small number of indents, none of any great size, examples of which survive in All Saints, Pavement, Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, and St. Sampson's. However, the work of Dodsworth, Johnston and Keep in the 17th century in recording monuments surviving in their time shows that several figure brasses did exist, although the number was probably never very great. Dodsworth records in St. Mary, Castlegate, 'a very fair engraven tomb with the pictures of a man and his wife', with an inscription to William Graa and his wife Johanna (Bodleian, MS. 157, f. 24v; MS. 161, f. 35). Only the tomb-chest now remains. Johnston, on 16 March 1669, recorded an indent in St. Denys' which had 'the portrature of a man and woman under it but now torne of which they say was for an Earle Percy' (Bodleian, MS. Top. Yorks. C14, f. 107). Two figure indents in All Saints, Pavement, retained complete brasses in 1669. The monuments were both to mayors and their wives: that to Thomas Beverley, 1475, and his wife Alice had standing figures, a brass inscription and corner shields, and that to John Gyliot and his wife Joanna had kneeling figures, an inscription and corner shields-of-arms (ibid., f. 110v). Indents for quatrefoils survive at All Saints, Pavement, and St. Denys'. A plate with black-letter inscription to Roger de Moreton, 1382, and his wife Isabella, 1412, is now in All Saints, Pavement, but the original indent, with indents for corner shields, is still at St. Saviour's. In St. Cuthbert's the brass to William Bowes, 1439, and his wife Isabella, 1435, is now covered over: it is recorded as having indents for four corner shields (Mill Stephenson, 'Monumental Brasses in the City of York', YAJ, xviii (1905), 45–6). Several good black-letter inscriptions survive on their own, varying in date from 1458 to 1517.

From the mid 16th to the mid 17th century Latin was abandoned for English, usually in capital letters. An early example recorded by Stephenson was at St. Cuthbert's, to William Holmes, 1558. Two half-length portrait plates, to Christopher Harington, 1614, and Robert Askwith, 1597, are shown in Plate 40. Latin reappeared in the reign of Charles II, but confined to certain monuments where a display of erudition was called for. Lettering, following good classical models, was mainly italic lower case or a mixture of capitals and lower case italic letters. This is exemplified in three signed works by Joshua Mann, of 1680 and 1681. There are several inscriptions on brass showing a tradition of good lettering throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, with a large concentration in the first decade of the 19th century.

Carved Stonework. There are some reset 12th-century corbels at St. Denys', of a type discussed in York iv, xlv; they represent animals' heads, each occupying almost the entire stone. Another type, with a mixture of animal and human heads, is found reset in the tower of St. Saviour's; these must have formed part of a corbel-table.

Later stonework is mostly in the form of label-stops or corbels carved with heads or half-length figures of angels bearing shields. These are mainly 15th-century in date, with examples of the 16th century in St. Helen's and St. Michael-le-Belfrey.

Chests. The earliest surviving chest in the area is one of 13th-century date in the Merchant Adventurers' Hall (Plate 35) which is reinforced by vertical iron bars. Two chests reinforced by a grid of iron bars are probably 16th-century. One is also in the Merchant Adventurers' Hall, the other in St. Denys' (Morrell, Woodwork, Fig. 139).

Coffins and Coffin Lids. As the custom of burial just below ground level, with the coffin lid level with the floor, was superseded from about the middle of the 14th century by deeper burials marked by floor-slabs, there are very few coffin lids still in situ. A major exception is at St. Saviour's, where excavation to an earlier floor level in 1976 exposed various slabs, including undisturbed coffin lids. The best bears a fine Lombardic inscription in Latin on two long sides to Robert Verdenel, dead by 1281, and an incised crescent moon and sunburst at the top. Another coffin lid still in situ is in Holy Trinity, Goodramgate. Like the Verdenel one, it is of yellow stone and tapered but bears a defaced Latin inscription at the top and has an incised stepped cross-base at the bottom. A recently discovered stone in St. Mary, Castlegate, also has the inscription at the top, but in French. Another stone with a similar inscription in French came from St. Helen's and is fully described in the YPS Handbook (1891), 89. There are numerous slabs not in their original positions which may have been coffin lids. A number of cross-slabs intact from cross-head to base appear too small to have been the lids of full-size coffins and may have been either grave markers or the lids of infants' coffins. One lid known to belong to a child's coffin, now in the Yorkshire Museum, was found in Fossgate in 1887, and is only 1 ft. 10¼ in. long. It bears a foliated cross on a calvary base, with a brooch buckle on the shaft. The coffin may have been buried originally in the Carmelite Friary church on the E. side of Fossgate. There are two major cross-slabs bearing symbols. One from St. Denys', now in the Yorkshire Museum, possibly to John de Kirkham, potter and bell-founder, whose widow desired in her will to be buried in the church, shows a bell and a cauldron-shaped brazier or small furnace. A similar object, possibly a cauldron, is associated with a fish at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate. The St. Denys' slab is incomplete, with the base missing. From the length, 3 ft. 8½ in., it could have been a full-length coffin lid originally but the Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, slab is complete, only 3 ft. 0½ in. long, and from the symbols is unlikely to have belonged to a child. Other survivals are mainly fragmentary.

Communion Rails. Of the three sets of early 18th-century rails in the area, the one at St. Michael, Spurrier-gate, enclosing the altar on three sides, is undated. The other two are dated to 1712 at St. Michael-le-Belfrey, by William Etty, and to 1715 at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, by John Headlam, carpenter, and both have the semicircular front gates found slightly later at St. Martin-cum-Gregory, of 1753 (York III, liii). A fourth set, of 1717, at St. Martin, Coney Street, now destroyed, is said to have resembled those of St. Michael-le-Belfrey. Semicircular gates also existed in St. Cuthbert in 1851 and survived at St. Denys' until 1875, St. Helen's until 1858, St. Margaret's until 1852, and St. Sampson's until 1875.

Font-covers. The restored font-cover at St. Martin, Coney Street (Plate 36), belongs to a group of early 18th-century oak font-covers with scrolls surmounted by a dove (York III, liii, Plate 28). It is dated 1717, as is a similar cover to which an extra tier was added in 1794, formerly at St. Saviour's but now in Holy Trinity, Micklegate (York III, 15, Plate 28). A font-cover formerly at the Bedern Chapel (Morrell, Woodwork, 172, Fig. 202) belongs to the same group. Another oak font-cover of the same type, very simplified and of one tier only, survives in a decayed condition in the Minster stonemasons' yard; its provenance is unknown. The font-cover at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, provided in 1787, consists of three moulded tiers with a ball-finial.

Galleries. Four of the mediaeval churches acquired galleries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries but only that at St. Michael-le-Belfrey, built at the W. end of the church in 1785, survives.

(I.R.P.)

Glass. The mediaeval glass is to be found principally in six churches - All Saints, Pavement (1), Holy Trinity, Goodramgate (2), St. Denys' (6), St. Martin, Coney Street (10), and the two churches dedicated to St. Michael (12, 13); small amounts remain in St. Mary, Castlegate (11) and St. Helen's (8); in St. Cuthbert's (5) only fragments survive.

Chronological Summary

In St. Denys' is reused glass from a lancet, the only 13th-century glass to survive, and valuable for both its design and its iconography. The 14th-century glass is very good, the best examples from the first half of the century being in the N. chapel and N. aisle of St. Denys' and, reset, in the E. window of St. Michael-le-Belfrey. A few figures and some canopy-work survive in St. Mary's and St. Martin's, and some good heraldry in Holy Trinity. From the second half of the century there remains the glass formerly in the E. window of St. Saviour's (15), now transferred to the W. window of All Saints'. This includes a remarkable series of panels illustrating the Life and Passion of Our Lord, and showing the softer modelling in the drawing typical of the late 14th century, but at the same time very individualistic and unlike any other surviving glass in York (Plate 50), except some in St. Martin-cum-Gregory (York III, 24b). The 15th century is even richer in stained glass, the earliest being the Jesse window in St. Michael, Spurriergate, followed by that in the S. chapel of St. Denys'; although sadly mutilated and jumbled, this latter clearly represents windows of a high quality. To the second quarter of the century belong the fine series in the S. aisle of St. Michael, Spurriergate - apart from the Jesse mentioned above - and the W. window of St. Martin's, which is closely dated to shortly after 1440, though now reset in a new position. Later in the century come some figures at St. Helen's and the surviving panels from the E. window of St. Martin's. The excellent but rather battered E. window of St. Denys' can be dated to between 1452 and 1455; unfortunately the state of the stonework has prevented the replacement of the glass since the last war, and it still remains in store. Perhaps the most outstanding of the late mediaeval glass is in the E. window of Holy Trinity, dated by its inscription to 1471. Its remarkably fine quality refutes theories about the decline of the art in the late 15th century. The mediaeval sequence is rounded off by the glass in the N. and S. aisles of St. Michael-le-Belfrey provided by various donors between 1525 and 1540 at the rebuilding of the church.

The post-Reformation glass is, as might be expected, mostly secular in character. In the second half of the 17th century the Gyles family kept the craft alive. Most of the surviving panels are probably by Henry Gyles (1645–1709) who signed his work at the Merchant Taylors' Hall (38) (Plates 186, 187). Other works by him are in St. Helen's church, Gray's Court (35), No. 35 Stonegate (488) and the Castle Museum; a flower-panel in No. 9 New Street (287) (Plate 187) may also be by him. Some panels in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Plate 187), although undoubtedly by Henry Gyles, can no longer be accepted as the surviving parts of the W. window of the Guildhall, removed in 1862 (York Educational Settlement, York History No. 3 (n.d.), 109–117, where it is erroneously described as the S. window). With the death of Henry Gyles the continuity of glass-painting in the city was interrupted for nearly half a century. The glaziers working in the first half of the 18th century were for the most part little more than jobbing plumbers, employed on repairing damage, putting in plain glass and releading. The churchwardens' accounts, for example, of Holy Trinity for the 17th and 18th centuries are full of entries illustrative of such operations. It has already been noted (York III, lii) that the period after 1730 saw the greatest damage done to the mediaeval glass, and this was no doubt largely due to lack of practising glass-painters. Towards the middle of the century Jeoffrey Linton, who was free as a plumber and glazier in 1733, carried out repairs at St. Michael-le-Belfrey for which he was paid £6. 17s. in 1749 (YML, E4a). A roundel with his name and the date 1746 survives in the tracery of St. Michael's E. window, and in the same church, in window sV, is a winged heart with the same date, painted very crudely in yellow stain, possibly by the same artist. From the second half of the 18th century several works survive by William Peckitt (1731–95), including a panel of 1765 replacing one which he painted in 1754 to obtain his freedom (J. Br. Soc. M. G-P., xv (1974–5), 17–22), and which until the last war was in the Guildhall (York IV, Plate opp. p. xlix). This and a large floral and geometrical panel from the hall window of No. 35 Stonegate (Plate 186) are now in the City Art Gallery. Another panel, almost certainly by Peckitt, illustrating his engraving technique, remains in No. 9 New Street (Plate 187). A possible associate or apprentice of Peckitt, Thomas Hodgson, painted a royal arms and a city arms in 1801 in No. 25 High Petergate (335). Other work by this firm formerly existed in the now-demolished church of Christ Church, King's Square. Later in the century John Joseph Barnett provided an extensive series of flashed and engraved roundels of great charm for St. Michael, Spurriergate, one of them signed and dated 1821.

Critical Survey

The early 13th-century light in St. Denys' shows a pattern of glazing not otherwise found in York except in the more elaborate late 13th-century windows of the chapter house in the Minster; it comprises small coloured medallions containing figure-subjects set at regular spacing within a monochrome field of naturalistic grisaille. The two very decayed roundels here have been identified as scenes from the story of Theophilus (Arch. J., ciii (1947), 133), the only survival of this subject in York glass (Plate 55). Among the 14th-century glass of St. Denys' is what must originally have been a very fine Jesse window, now appallingly mutilated, filling the E. window of the N. chapel. The windows in the N. wall of the same church include a donor offering his window, and two John the Baptist scenes (Plate 60), one of them painted from the same cartoon as the similar scene in St. John, Micklegate (York III, Plate 31), now in the Minster. The assembled glass of much the same date in the E. window of St. Michael-le-Belfrey contains, inter alia, some panels with scenes from the life of Our Lord (Plate 49). Border details here suggest that some of the glass came from a window given by Richard Tunnoc, the wealthy bell-founder, who also gave a window in the N. aisle of the Minster. This glass in St. Michael-le-Belfrey and St. Denys', together with glass in the Minster and elsewhere in the city (York III, liii), illustrates the remarkably capable and productive work of the York glaziers in the second quarter of the 14th century. Here also the change from the entirely pot-metal work of the St. Denys' roundels to the combination of pot metal enhanced with extensive use of yellow stain shows clearly the revolution this new technique helped to effect in the production of stained-glass windows. The paucity of glass from the second half of the 14th century is probably due to the mortality from the Black Death among patrons and glass-painters alike. The recovery from this, near the end of the century, is illustrated by the series of Passion scenes now in All Saints' (Plate 50), which shows a new vitality and provides many interesting iconographical details (Plate 48). The emphasis on the Passion rather than the early life of Our Lord is possibly due to the Black Death and a reminder that the plague was still appearing spasmodically in the city. The Passion shield also in this window may point the same moral (Plate 55).

The earliest 15th-century glass is the Jesse window in St. Michael, Spurriergate (Plate 52). Badly jumbled over the centuries, its restoration has revealed painting of excellent quality. Although the late J. A. Knowles tried to link this glass in date with the late 15th-century glass in the S. nave clerestorey of Great Malvern Priory (Ant. J., xxxix (1959), 279–81), its affinities seem to lie much more closely with the glass produced by the Oxford school under Thomas of Oxford for the chapel at Winchester College in the last decade of the 14th century. The similarities may merely reflect the general influence of the international Gothic style at this period, but they tend to put the date of the York glass back to the early years of the 15th century where it overlapped and blended with the softer style associated with the school of John Thornton. The links with this latter style include the decoration of capital letters with faces (Plate 53), an idiosyncrasy occurring three times in this window (including one misplaced in the adjoining window) and found elsewhere in York only in Thornton's E. window at York Minster (1405–8). The St. Michael's window is surprisingly the only successor in York to the two 14th-century Jesse windows, namely those in the S. nave aisle of the Minster and the N. chapel of St. Denys'. Two windows in the S. chapel at St. Denys', dating from c. 1425, are of more orthodox York style. The E. window is now fragmented and jumbled with pieces from more than one window, but some details belong to a St. Catherine cycle, to whom the chapel was dedicated (Plate 47). The S. window contains in the tracery the reset remains of a finely-painted angelic orchestra (Plate 55), and in the central light is an interesting portrayal of the Virgin in a rayed mandorla wearing a triple crown. This same detail appears a few years later in the glass at St. Helen's where the patron saint of the church is also shown. The remainder of the glazing in St. Michael, Spurrier-gate, from the second quarter of the century, and now assembled in windows of the S. aisle, is of a high quality. The E. window of this aisle illustrates the technique, rare in York, of fluxing coloured pieces on white glass (Frontispiece).

In the S. wall of St. Michael's, window sIII contains eight panels depicting a fine Nine Orders of Angels (Plate 52). That this was a popular theme in York is shown by its appearance here and at All Saints, North Street (York III, Plate 101), occupying in both places the main lights of windows. In addition it appears in its more usual position in the tracery lights both in the E. window of the Minster and in the W. window of St. Martin's (Plate 54), expanded to ten orders in both so as to suit the symmetry of the stonework. The varying treatments of the theme are interesting. In both tracery examples, the angels appear as single figures; in the All Saints' version a representative of each Order heads a procession with a textual description of its function in the hierarchy, whereas in St. Michael's the identifying names alone are given, but each Order is represented by three figures, thus emphasising the mystical division into three hierarchies of three orders each. Further evidence of the flourishing local schools is given by the W. window of St. Martin's, where the glass, once again in honour of the patron saint, was given by the vicar, Robert Semer, just before his death in 1443. Here is depicted the patron saint himself surrounded by a number of haphazardly-arranged scenes from his life (Plates 54, 56, 61). Although the colouring and overall effect are good, the draughtsmanship shows a distinct deterioration from previous standards. J. A. Knowles has suggested that it was the work of the glass-painter responsible for the St. Cuthbert window in the Minster, possibly John Chambers junior (YAJ, xxxviii (1955), 183–4). The same workshop, perhaps under a new master-painter, may also have produced the E. window of St. Martin's, some panels from which survive in the S. transept of York Minster (sXXVII and sXXVIII); it is slightly later in date than the W. window, probably belonging to the decade 1450–60. With its great series of thirty panels, each portraying God the Father in majesty in a scene illustrating a verse from the Te Deum, it must have been one of the finest and most impressive windows in the city.

The second half of the 15th century provides two other notable windows. The E. window of St. Denys', now stored with the York Glaziers Trust, contains a central Crucifixion flanked by the Virgin (Plate 47) and St. John, and outside them the patron saints both of the church, St. Denys', and of the impropriating monastery, St. Leonard's. At the bottom of the window, now lost but recorded and drawn by Dugdale (College of Arms, MS. Yorkshire Arms, f. 127), was the donor, Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland, with his wife and family. Its date must lie between 1452 when one of the sons, William Percy, became Bishop of Carlisle, and 1455 when the earl was killed at the battle of St. Albans. The central figures in the main lights show some similarities with the Crucifixion figures in the E. window of St. Stephen's chapel in the Minster (window nII), where the glass, although very much a hotch-potch, may in part be associated with a chantry established there in 1459. The iconography of the Crucifixion scene is of interest in the portrayal of the Virgin turning away from the scene and in the drooping pose of the Crucified (see G. McN. Rushforth, Medieval Christian Imagery (1936), 193).

The last of this great series of 15th-century windows is the E. window of Holy Trinity (Plate 45). The glass was given by the rector, John Walker, in 1471, and exhibits painting of excellent quality. In its highly interesting iconography it celebrates the Corpus Christi (Plate 46) (a repetition of the scene in St. Martin's (Plate 46)), SS. George and Christopher (Plate 57), and the Virgin Mary. The Corpus Christi Guild and the Guild of SS. Christopher and George were the two most important guilds in York, and the donor was an important official in them. There is also an interesting Coronation of the Virgin (Plate 58) with the three persons of the Trinity portrayed as similar figures wearing imperial arched crowns (see Rushforth, op. cit., 390, 404–6). The window has been reduced in size since the 17th century when Johnston drew it with two additional rows of panels at the bottom. One of these rows contained five representations of the Virgin in a rayed mandorla, each with its own title - Domina Mundi, Regina Celi, Mater Christi (carrying the infant Jesus), Mater Ecclesie and Imperatrix Inferni. When the window was altered in the 18th or 19th century some of these figures were moved to the E. window of the N. aisle (Plate 55). A good deal of confusion, however, still remains as to the original arrangement of the glass at the E. end of the church. In Johnston's main drawing (f. 133) he shows in the bottom row only a figure of St. Paulinus, now in the E. window of the S. chapel. In a different entry (f. 173v), however, he records along the bottom row donor figures kneeling in each light before a seated bishop. The kneeling donor in the central light is himself depicted as a bishop, and is identified by Dodsworth (Bodleian, MS. 161, f. 40v) as William de Egremond. This must be the suffragan bishop of Dromore who died in 1502 (YASRS, cxxix for 1966 (1967), 64). A figure of St. William, probably from this row, is in the E. window of the N. aisle. There must have been other figures elsewhere belonging to a similar glazing scheme as there is a scroll, shaped exactly as the other surviving ones, and inscribed 'Sancta Maria', now placed over the 'Mater Christi' figure. The deep veneration of the Virgin in York is remarkable, going back to the early 13th-century glass at St. Denys', and is particularly apposite for Holy Trinity where the establishment of a chantry to the Virgin in 1316 led to the building of the first of several rows of houses to provide funds for such chantries. Possibly as a corollary to the popularity of the Virgin is the occurrence in Holy Trinity of groups of Holy Families (Plates 51, 59), following the example set by the Minster and by one group in St. Martin's (Plate 51). The window as it now stands was studied in some detail by J. A. Knowles (YAJ, xxviii (1926), 1–24).

The last examples of mediaeval glass are to be found in St. Michael-le-Belfrey, dating from between 1525, when the church was rebuilt, and c. 1540. The glass has been largely reassembled from its jumbled pre-war state, and the names of various donors added from Dodsworth's transcripts. The large single figures, strong in colour but weak in draughtsmanship, are more interesting historically than artistically (Plates 49, 63). The small panels of the Thomas Becket series (Plate 63), more of which are to be found in the Minster, are a noteworthy addition to the iconography of that saint (see P. Newton, 'Thomas Becket', Actes du Colloque International de Sédières (August 1973), 258–9). The late Dean Milner-White commented on similarities between the St. Michael's glass and that at Fairford, of c. 1500 (Sixteenth Century Glass in York Minster and in the Church of St. Michael-le-Belfry, St. Anthony's Press, York (1960)), and suggested that the York glazier John Almayn may have been concerned with both churches. J. A. Knowles, however, ascribed the Belfrey glass to the York glazier William Thompson, who is known to have given one of the windows (Ant. J., xxxix (1959), 282).

After the Reformation the craft found few customers and dwindled accordingly. Henry Gyles kept up an acceptably high standard, and his glass in the Merchant Taylors' Hall deserves commendation for good colouring and draughtsmanship (Plates 186, 187). William Peckitt is better known, and stands perhaps as the foremost glass-painter of the 18th century. He supplied glass to many other places besides York, as far afield as Oxford and Exeter. His draughtsmanship, especially of faces, was very weak but his feeling for design and, in particular, abstract patterns was consistently good. One of his principal contributions was his revival of the use of pot metals and the consequent reintroduction of flashing for ruby glass, a practice continued and elaborated with other colours by Barnett in the 19th century. From then on, the techniques of flashing and engraving rapidly found their way into the rectangular fanlights used in most of the small Regency houses and terraces in York.

Finally some miscellaneous comments may be made. The danger of dating by a superficial use of stylistic criteria is emphasised by the frequent re-use of cartoons at known different dates. This custom has been frequently commented on in the writings of J. A. Knowles (see especially J. Br. Soc.M.G-P., October 1925). The St. Denys' example is noted above. At St. Martin's are two versions of the Trinity, of which one (in sIV) is repeated in Holy Trinity (1), and the other twice in St. Martin's glass, respectively in the tracery of sIV and the former E. window, now in the Minster (sXXVII).

The frequency with which donors appear in the windows would perhaps be less noticeable had not so much of English stained glass been destroyed. They survive in St. Denys', twice (Plate 50), in St. Michael-le-Belfrey in the E. window and in five of the 16th-century windows, in St. Helen's W. window, in St. Martin's W. window (Plate 54) and in Holy Trinity's E. window (Plate 46). They are also known to have existed in the E. windows of the chancel and S. chapel of St. Denys', in the E. window of St. Margaret, Walmgate, and perhaps at Holy Trinity in the E. window of the S. chapel. Heraldic evidence for donors is not to be seen at all, though a certain amount formerly existed. But the evidence suggests that most of the donors were local merchants and parochial clergy rather than the nobility.

The survival in York of so much stained glass, and in particular of representations of God, has often been the subject of comment, and has usually been ascribed to the firm control exercised by Lord Fairfax in 1644. Raine (Painted Glass, 2) writes of a tradition that Fairfax took out the windows. This may be an exaggeration of the clauses in the surrender articles which forbade damage to property, but the point should also be made that the glass had already survived the potentially equally destructive era of the Reformation in the previous century. It is, however, possible that Raine's tradition reflects an element of truth, as some of the glass does seem to have been removed during the Civil War period, and some of it may not have been replaced until many years later. This is suggested by the inconsistencies to be found in the accounts by the various late 17th-century antiquaries.

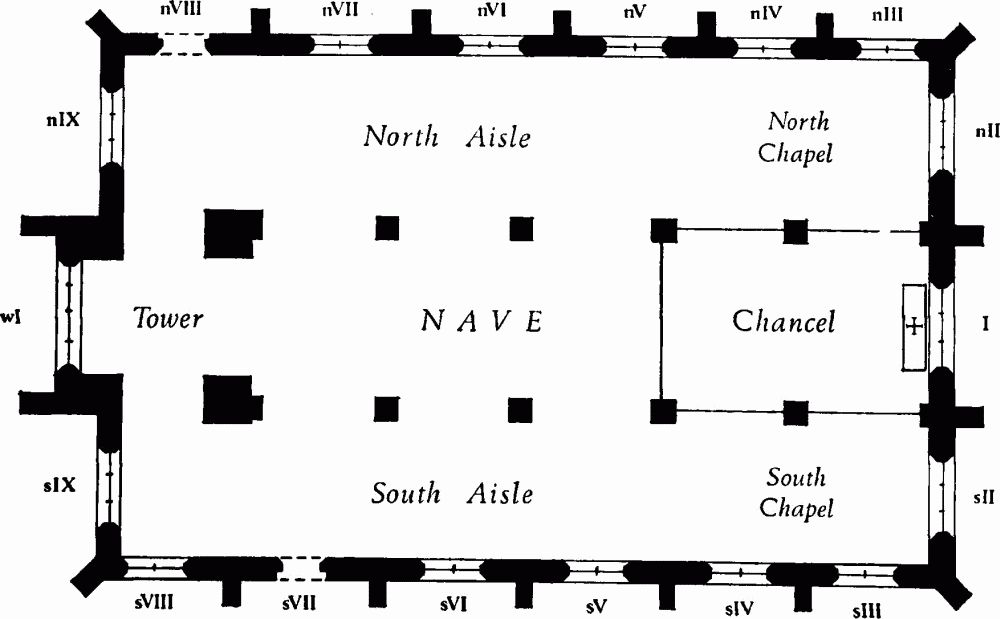

Identification System

The system employed in this volume to identify windows as well as individual panels and tracery openings within each window differs from that used in previous Commission Inventories. The new system is that recommended and used by the international Corpus Vitrearum committee for their publications, and is summarised as follows:

1. Numbering of windows.

(a) Numbering in any building begins with the eastern window on the main axis, and then proceeds in a westerly direction on both north and south sides. Every window is given a number.

(b) The east window on the main axis is numbered 'I'. The adjacent windows on the east wall to north and south, that is to say the east windows of the north and south chapels or aisles, are numbered nII and sII. The numbering then proceeds from east to west along the north and south walls - nIII, nIV, sIII, sIV etc., to include the west windows of the aisles. The west window on the main axis is number 'wI'. Upper or clerestorey windows are differentiated by a capital letter - NII etc.

The plans of those churches which contain substantial amounts of stained glass have been given this new numbering. See diagram below:

2. Numbering within each window.

(a) The main lights are divided up into their constituent panels.

(b) The panels are numbered as horizontal rows, beginning at 'i' for the bottom row. Each light is given a lower-case letter starting with 'a' on the left facing the window. Thus the lowest left-hand panel is numbered 1a, the panel above it 2a; the panel to the right of 2a is 2b.

(c) The tracery openings are treated in a similar manner, being divided as far as possible into horizontal rows which are denoted by capital letters, with the openings numbered across each row; thus the bottom line starts on the left with A1, and the row above with B1.

The diagram opposite shows this system applied to the east window (I) of St. Michael-le-Belfrey.

(T.W.F.)

Fig. 2. (12) St. Michael-le-Belfrey. Window I. To illustrate method of numbering panels.

Lord Mayors' Tables. These are wooden boards, usually of 18th or 19th-century date, painted with chronological lists of lord mayors who lived in the parish.

Mace-rest. One, bearing the dates 1707 and 1801, is in the chapel of the Merchant Adventurers.

Monuments and Floor-slabs. Most surviving mediaeval monuments are limited to floor-slabs with a simple marginal inscription, as with that of 1405 to Robert Ward in St. Denys', or sometimes slightly more elaborate in the style of contemporary brasses with corner medallions showing the Evangelists' symbols, as on a slab in St. Michael, Spurriergate, identifiable (Bodleian, MS. Dodsworth 161, f. 36v) as that of Alan Hamerton, 1405, and his wife Isabella. One unusual slab in St. Saviour's bears no name, but on all four edges is the exhortation 'Orate pro me'.

There is a small group of later monumental effigies. The Watter monument in St. Crux Parish Room (Plate 41) and the monument to Dorothy Hughes in St. Denys' (Plate 42) are good examples of early 17th-century design, combining large-scale effigies with smaller allegorical carving. The slightly later Sheffield monument in St. Martin, Coney Street, combines allegorical figures with portrait busts (Plate 41). In contrast with the recumbent figures on the Watter monument are the self-assured standing figures of Robert and Priscilla Squire at St. Michael-le-Belfrey (Plate 44) on an early 18th-century monument attributed to John Nost and Andrew Carpenter. Later monuments abandon large representations of the deceased, as in the monument to Sir Tancred Robinson, 1754, in St. Crux Parish Room, by Robert Ayray, which adopts the popular form of the pyramidal background but incorporates a roundel containing a portrait bust (Plate 43).

As in S.W. York, there is a large group of cartouches. The earliest, to Anne Walker, 1687, in St. Michael-le-Belfrey, which is similar to one to Judith Frewen, 1666, in the Minster Lady Chapel (Morrell, Monuments, Plate XL), concentrates on scrolls mixed with foliage, as does that to John White, 1716, in the same church. The rest mostly incorporate cherubs' heads as in St. Michael-le-Belfrey to Mary Woodyeare, 1728 (Plate 42), and to Thomas James, 1732; in St. Michael, Spurriergate, to John Harrison, 1729; and in St. Cuthbert's to Charles Mitley, 1758 (Plate 42), possibly carved by Mitley himself, with the inscription added after his death. The Woodyeare cartouche is the most elaborate, incorporating a shield-of-arms, a foliage garland and a skull. The garland had been previously used on the Perrott monument, 1721, in St. Martin-cum-Gregory, and the skull on the Etty and Carter monuments, both of 1708, in All Saints, North Street, and St. Martin-cum-Gregory, respectively (York III, Plate 32). The Sowray cartouche at St. Mary, Castlegate, also of 1708, is a variant of the same type, with a grotesque mask instead of a skull. Smaller cartouches, framing shields-of-arms, are used on wall-monuments, usually within an architectural framework.

Monuments with an architectural framework of columns or pilasters supporting a cornice or pediment were popular during the first half of the 18th century. Often the flanking elements were reduced to simple recessed strips either side of the inscription. An early variant of this type is at St. Crux Parish Room to Roger Belwood, 1694 (Plate 43), which emphasises the comment 'He was a learned man' by forming the 'pilasters' of piled-up books, a conceit first used in York on the tomb of Archbishop Frewen, 1664, in the Minster Lady Chapel (Morrell, Monuments, Plate XXIII), and previously on Bodley's monument at Merton College, Oxford, in 1612 (RCHM, City of Oxford, Plate 143).

Monuments incorporating a pyramidal background achieved great popularity during the second quarter of the 18th century, and influenced later developments. The earliest example of this type to use large-scale figures in York is the Thomas Watson Wentworth tomb, 1723, by Guelfi of Bologna, in the Minster (Morrell, Monuments, 41), but the pyramidal slab used for an inscription appears two years earlier, in the monument to Lady Frances Graham, 1721, in Holy Trinity, Goodramgate. Urns and sarcophagi appear with increasing frequency throughout the second half of the 18th century as symbols of mortality, and become standard elements in the 19th century. The draped urn on the monument to Thomas Payler, 1795, in St. Helen's, is a rare example in York of Coade stone.

From c. 1770 onwards monumental sculpture in York is dominated by the Fisher family. Their best work is before the 19th century, notably in the monuments to William Hutchinson, 1772 (Plate 43), and Henry Waite, 1780 (Plate 43). The monuments to Rachel Sandercock, 1790, in the Unitarian Chapel, St. Saviourgate, and to Robert Welborn Hotham, 1806, in St. Denys', hark back to the Robinson monument in St. Crux Parish Room, each with a pyramidal background, and a sorrowing woman instead of a cherub standing by an urn. The suspended sword of the Hotham monument is in a long tradition of military or naval trophies. The monument in the Minster to Vice-Admiral Henry Medley, 1747, attributed to William Tyler (Morrell, Monuments, Plate XXXVIII), was probably the inspiration for the Robinson monument of 1754 (Plate 43).

Two interesting minor monuments are both to Atkinsons. That to Thomas Atkinson, 1798, in St. Saviour's, is a free version by John Atkinson of the monument to Elizabeth Scarisbrick in Holy Trinity, Micklegate, 1797 (York III, Plate 34). That to James and Ann Atkinson, 1839 and 1840, in St. Helen's, is an elaborate Gothic monument complete with cusps, crockets and pinnacles. Epitaphs throw interesting sidelights on British military, colonial and social history: for example those to Henry Richards, 1783, who fought at Dettingen, Fontenoy, and Culloden (All Saints, Pavement); Elizabeth Bath, 1736, whose husband, Captain Lieutenant Bath, died in Minorca in 1718 (St. Michael, Spurriergate); Lieutenant Theophilus Garencieres of HMS 'The Queen', who died of yellow fever at St. Domingo, 1797 (St. Helen's); George Stevens Fryer, who died at Calcutta, 1844 (Holy Trinity, Goodramgate); and Tate Wilkinson, the original patentee and manager of the Theatre Royal, York, 1803 (All Saints, Pavement).

Paintings. Mediaeval wall-paintings are known to have existed at St. Saviour's but are now gone. There are two painted panels with arched heads at St. Cuthbert's depicting standing figures; these are hardly visible but may be 18th-century representations of Moses and Aaron. Reports of two inscriptions with figures painted on the walls in the same church, with 'old English text' and the figure of a cherub, suggest a 16th or 17th-century date (YG, 28 Jan. 1843, 6).

Plate. Only a few pieces dating from before the Civil War survive. The earliest and most interesting cup, with cover, in St. Michael-le-Belfrey, is Elizabethan, made in London in 1558–9 and richly ornamented ('An Elizabethan Communion Cup', Country Life, 5 Dec. 1947). The typical 18th-century communion cup is best represented by two London-made cups of 1757–8 in St. Martin, Coney Street. The examples of goldsmiths' and silversmiths' work belonging to the York churches are complemented by an important collection of civic plate in the Mansion House belonging to York Corporation, and lesser collections in the possession of the Merchant Adventurers and the Merchant Taylors.

Base-metal plate is well represented. There is a good group of pewter flagons and a pewter alms-dish of 1675, presented to St. Martin, Coney Street, now in the Yorkshire Museum. Two brass alms-dishes are worthy of note: one at St. Michael, Spurriergate, with a perforated pattern, and another at St. Helen's with the figures of Adam and Eve. Both of these dishes are probably Augsburg work of the 16th century.

Pulpits. There are similar hexagonal pulpits with enriched arches on each face at St. Cuthbert's and St. Denys'. Similar carving on a pew inscribed 'Done at the expense of the Parish, 1636' is recorded by Morrell (Woodwork, 165) as formerly at St. Cuthbert's, and this may provide an approximate date for both pulpits. A more elaborate version, with an inscribed band, was made in 1634 by Nicholas Hall for All Saints, Pavement. It is similar to one in St. Martin-cum-Gregory made in 1636 by John Harland (York III, Plate 38). All Saints, Pavement, retains its sounding-board; that at St. Denys' is recorded by Morrell (Woodwork, 161). The shaped panels used on the sides of the 1675 pulpit at All Saints, North Street (York III, Plate 38) are repeated in the pulpit of the Merchant Adventurers' chapel (Morrell, Woodwork, Fig. 180), which was used by the Huguenots in York after 1687. The early 18th-century pulpit, now in Halifax, from which John Wesley preached in St. Mary, Castlegate, in 1768, has fielded-panel sides, and a sounding-board with pedimented sides decorated with foliage and a cherub's head.

Reredoses. There are three 18th-century reredoses, those of St. Michael-le-Belfrey, made by William Etty in 1712, and St. Michael, Spurriergate, being of high quality (Plate 37).

Seating. Pews were introduced into parish churches in the 17th century. Holy Trinity, Goodramgate, retains a notable series of box-pews of the 18th century preserving the 18th-century liturgical arrangement; they incorporate earlier panelling, presumably from 17th-century pews. The Merchant Adventurers' chapel is fitted with panelled seating of the late 17th century, arranged in the manner of a college chapel.

(I.R.P.)

Mediaeval Hospitals

York is unique in England for the large number of substantial communal buildings which survive. They provide an interesting illustration of religious, social and commercial life of the Middle Ages. The principal mediaeval hospital in York and one of the greatest in England was St. Leonard's, which occupied a site in the W. corner of the Roman fortress, and therefore immediately inside the city wall where it was protected externally by St. Mary's Abbey (York IV, 3–24). It was established on this site by William II in the late 11th century and was originally known as St. Peter's. Little is known of the buildings of the hospital; the existing remains all lie near or against the boundaries of the large site. It is probable that the ruined early 13th-century building in Museum Street, near the public library, represents a first-floor infirmary hall with a chapel projecting at right angles to the main axis, rather similar to St. John's Hospital at Canterbury (W. H. Godfrey, The English Almshouse, Fig. 15).

The other hospitals in the central area were associated with guilds. At the Merchant Adventurers' Hall there was a hospital, usually known as Trinity Hospital, in the undercroft below the great hall. The precise arrangement is not known, but the building as it survives consists of a large room divided centrally by a row of posts, with a chapel projecting at the S.E. end, not axially but offset to one side. At St. Anthony's in Peasholme Green there was a similar arrangement of a hospital occupying the ground floor below a first-floor hall, but the position of the chapel cannot be positively identified; it may have been at the S.W. end, and aligned at right angles to the hospital. At the Merchant Taylors' Hall, a maison dieu was referred to in the 15th century. By the early 18th century it had been demolished, but it is said to have stood near the church of St. Helen-on-the-Wall. It was probably a detached building in much the same position as the almshouse built in 1730.

Priests' Colleges and Houses

The Bedern (33) and St. William's College (34) both served similar functions in providing residential accommodation, the former for Vicars Choral of the Minster, the latter for the Minster chantry priests. The architectural forms taken by the two establishments were quite different. The Bedern, founded in the 13th century, occupied a large site and had apparently a fairly dispersed layout with a number of buildings, of which two survive in poor or ruinous condition, namely the hall and the chapel, both built in the mid 14th century. The hall is a unique example in York of a stone-built open hall with an outstanding, though mutilated, roof incorporating scissor-braced rafters. The service end has gone completely but there is an indication of a former canopy over the dais at the upper end, a feature not recorded elsewhere in the city. The chapel was about the same size as the hall and also had a scissor-braced roof, now dismantled. There is some evidence that the vicars had individual houses, reminiscent of, though not necessarily similar to, the well-known examples surviving at Wells.

St. William's College is of later date. Founded in the mid 15th century, it is on a more limited site and consists of a single building, started in c. 1465, with all the accommodation compactly arranged on two storeys around a small enclosed courtyard. The original internal planning is not entirely clear because of later division into tenements followed by extensive restoration early in the 20th century. The series of doorways around the courtyard suggests lodgings with separate entrances. The ground floor has stone walls but the upper storey is entirely timber-framed. It must be one of the largest framed buildings in the country and has architectural detail superior to any other in York.

A number of small establishments for the accommodation of chantry priests existed in the city. These included the Holy Priests' House, Peasholme Green, of which there are no remains, and Church Cottages, Nos. 31 North Street and 1, 2 All Saints' Lane (York III, (104) 98b), which provided chambers for five priests and a small common hall. Bowes Morrell House, No. 111 Walmgate (537), has the same form as the latter and may also be interpreted as a priests' house. Jacob's Well, Trinity Lane (York III, (125) 109), accommodated at least two priests.