Pages xxxiii-xliv

An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 1, South west. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1931.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

HEREFORDSHIRE Vol. I

Sectional Preface

(i) Earthworks, etc., Pre-Historic and Later.

Herefordshire, as a county, is peculiarly rich in earthworks, for not only is the pre-historic period well represented but the mediæval defensive earthworks are both numerous and important.

The S.W. section of the county, dealt with in the present volume, contains one megalithic monument of first rank, namely Arthur's Stone, in Dorstone parish, which is the chamber and entrance of a barrow, probably a long-barrow, from which the superincumbent earth has been entirely removed, leaving only the smallest traces of the original form of the mound. Again, a mound in St. Weonard's parish, which was opened in 1855, was found to contain two cremationburials.

No recognisable remains have yet been found of any neolithic camp, but of the camps now generally associated with the early Iron Age, there are several important examples. Of these, Eaton Bishop, Walterstone, Aconbury, Dinedor and Little Doward (Ganarew) may be mentioned, the first being a promontory-camp and the others hill-top or contour camps. The defences, except at Little Doward and Walterstone, consist of a single bank only, and the entrances, where they survive in anything like their original form, are all of the turned-in type. Little Doward has remains of a double rampart and a smaller annexe defended only by a nearly perpendicular outcrop of rock, while Walterstone has a triple rampart.

At Longtown is a large rectangular earthwork partly occupied by the mediæval castle. The outline suggests the possibility of a Roman origin, but the imposing scale of the rampart and ditch, indicates that, in their present form, they belong to a later date.

There seems little doubt that the great travelling earthwork, known as Offa's Dyke, and probably constructed by that king against the Welsh, was not continued across the area under review. After striking the Wye at Bridge Sollers, the river itself seems to have formed the boundary through the rest of the county. This would seem to be confirmed by the Welsh names of several villages in the bend of the Wye and by the presence of such names as English and Welsh Newton on opposite sides of the river.

Another possible dyke exists on the S. bank of the river, outside the S.E. limit of the city, consisting of a small segment of land enclosed by a bank, which perhaps was once a bridge-head and is called Row Ditch, while on the opposite bank there is a length of ditch, also called Row Ditch, which extends in a N.E. direction. There is no evidence of the date of either of these works.

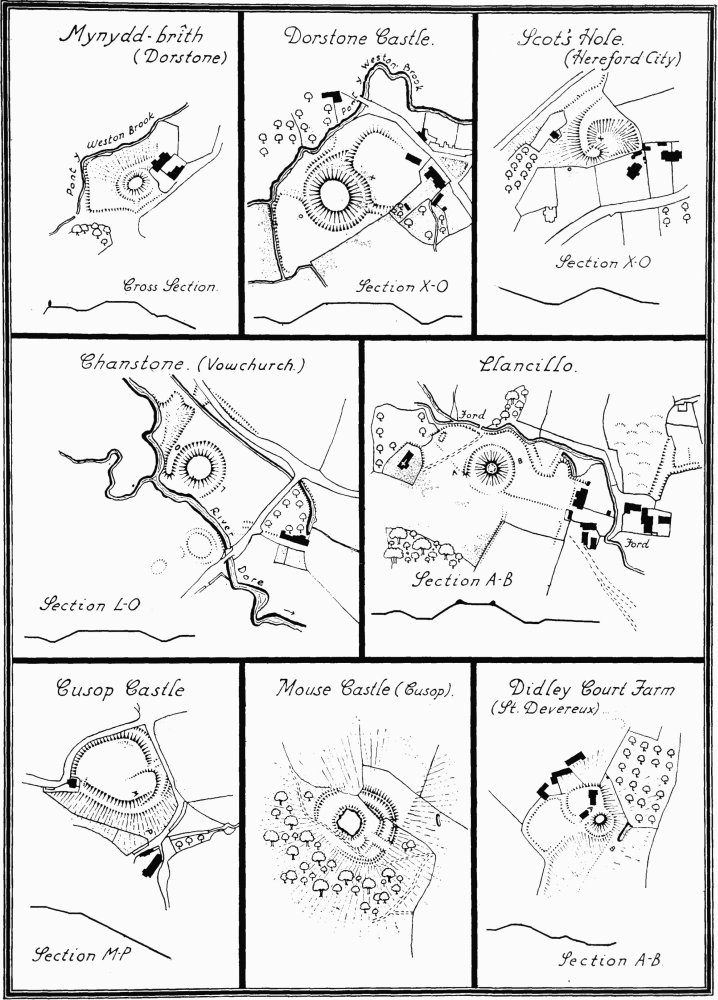

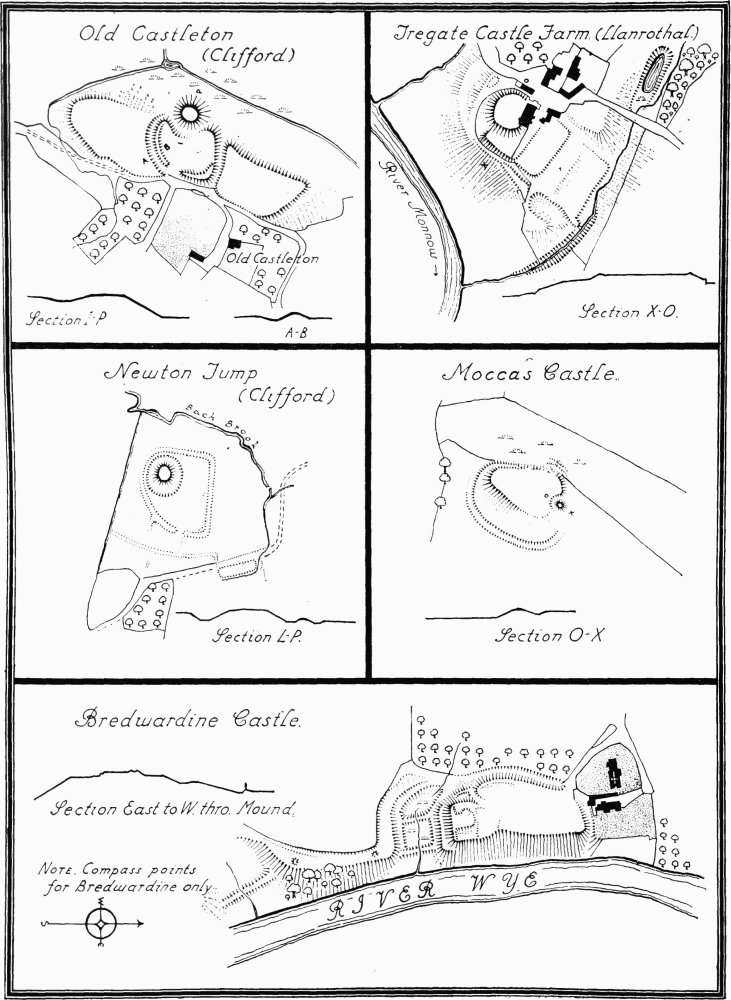

Of the numerous early and later Norman castles, the most important are those at Ewyas Harold and Kilpeck, both of the motte and bailey type and there are smaller, but well preserved examples at Dorstone, Orcop, Ponthendre (Longtown) and Old Castleton (Clifford). Other important castles of a kindred type, such as Clifford and Snodhill, may be of a later date or have been subsequently altered. In addition to these, there are, scattered about the country, numerous mounds of greater or less height, called Tumps. Most of these were, in all probability, smaller strongholds, which sprang up for defensive purposes in the Welsh Marches.

The later castles built of stone are commonly otherwise defended only by a moat or ditch. At Goodrich the great ditch is cut in the rock and the same is partially the case at Pembridge.

Some Mottes & Other Minor Earthworks.

Homestead Moats are almost entirely absent from the district. At Kilpeck, E. of the castle, is an enclosure probably defending the village.

An earthwork, called Scots' Hole, of indefinite form near Hereford is popularly connected with the Civil War, and the Bowling Green at Clehonger may also date from the 17th century.

Early in the 17th century a certain Rowland Vaughan devised and apparently executed a scheme for the scientific irrigation of part of the Golden Valley and published a book (1610) describing his operations. He appears to have lived in the parish of Bacton, but it is now impossible to identify with any certainty the ditches and weirs which date from his time.

(ii) Roman Remains.

The Roman remains are scanty and unimportant. The district was traversed by one certain Roman road, from Abergavenny to Kentchester, represented by the Gobannio—Magnis, M.P. xxii of the 12th Antonine Iter. A section of this road has been uncovered at Abbey Dore railway-station. Evidence of buildings has been noticed at Walterstone, on the same route, and at Whitchurch, near the Wye. An inscribed Roman altar does duty as a stoup at Michaelchurch. Reference has already been made to the possibility that Roman work may have formed the basis of the rectangular earthwork at Longtown. The general consideration of the Roman remains in the county will be reserved for the final volume.

(iii) Ecclesiastical and Secular Architecture. Building Materials: Stone, Brick, Etc.

Almost the whole of the area of the county of Hereford belongs geologically to the Devonian system, here represented by the beds of Old Red Sandstone. This forms the staple building material, though here and there, in the Woolhope district, the Malvern Hills and the N.W. corner of the county, there are outcrops of earlier formations. The Old Red Sandstone, in its upper beds, is of very shaly nature, but the lower deposits are more compact and form a tolerable building stone, which, however, rapidly weathers when used externally; its tint varies from grey to brown and dark red. In addition to this there are, here and there, surface deposits of calcareous tufa, which is sparingly used as building-material, though one church—Moccas—is almost entirely constructed of this substance. The only other local stone which need be mentioned is a type of breccia, found in the Malvern Hills, and used in a number of early fonts.

Brick is but little used, until the 18th century, except as a filling for timber-framing.

Timber, on the other hand, vies with the local stone as the favourite building-material. In the western and more mountainous parts of the county stone predominates, but in the eastern, flatter and more wooded parts there is a preponderance of the use of timber-framing. Stone slabs were commonly used for the roofing of churches and the larger secular buildings, but these in many cases were replaced later by red tiling.

Ecclesiastical Buildings.

Only Kilpeck and Peterstow churches have been noted as retaining structural evidence of pre-Conquest date; this is not surprising in view of the late date of the Saxon conquest of the country W. of the Wye; though it is indeed uncertain if the two examples in question are to be ascribed to Saxon or Celtic builders. Kilpeck retains only one angle of the early structure built with megalithic quoins, and Peterstow only the base of the N. nave wall, also built of large rough blocks of stone. To the end of the 11th century must be assigned the scanty remains of the chapel of the Bishop's palace at Hereford, which may be identified, with some probability, with the church built by Robert de Losinga, on the model of Charlemagne's minster at Aachen. The chapel was, in any case, a two-storeyed building of the type common in the Rhineland and adjoining districts and known as "Doppelkapelle." The greater part of the building at Hereford was destroyed in the 18th century, but drawings made, before this event, show its general form and arrangement.

The Cathedral at Hereford was begun under Bishop Reynelm (1101–1115) and completed in the middle or latter half of the 12th century. It was remarkable for certain unusual features in its design, including the lowness of the arch opening into the main eastern apse and the provision for two towers over the two E. bays of the presbytery-aisles. This last feature is unique in this country, but the surviving architectural evidence of the arrangement is conclusive.

Early Norman work, with herring-bone masonry, occurs at Bredwardine and rather later work at Moccas and Peterchurch. Both these buildings are unusually complete examples of the date, Peterchurch being planned on a fairly large scale.

The most usual 12th-century parish-church plan seems to have consisted of a nave, presbytery and apse, with or without a central tower. The lesser churches, however, consisted only of a rectangular chancel and nave and the cruciform plan was but little used; there are, however, remains of a cruciform church at Madley. Apses survive at Moccas, Peterchurch and Kilpeck. The important and well-known church at Kilpeck is the richest example of a peculiar type of carved ornament, which seems to be largely confined to Herefordshire and has certain features which appear to be of Scandinavian origin or affinity. This carving is elsewhere represented in the district at Rowlstone (chancel-arch and S. doorway) and in certain churches in the eastern and northern parts of the county. The curious carved projections below the gable at Kilpeck seem to be reproductions in stone of the carved ends of timber wall-plates.

The Cistercian Abbey of Dore, in the Golden Valley, founded about 1147, retains its transepts and eastern part of the church built about 1180 and exemplifying the usual Cistercian restraint and sobriety of ornament. The eastern arm was enlarged early in the 13th century by the addition of an ambulatory and chapel-aisle.

Amongst other late 12th-century work may be mentioned the tympanum at St. Giles Hospital, Hereford, the chancel-arch at Garway (part of the round nave of a Templars' church), and the reconstructed chancel-arch at Bridstow.

The 13th century is best represented by the Lady Chapel and other parts of Hereford Cathedral, the eastern parts of Abbey Dore, the arcades and W. end of Madley (a remarkable church with an interesting architectural history), the nuns' church at Aconbury, and the arcade at Kingstone. The late 13th-century N. transept at Hereford Cathedral, with its rather unusual arches, struck from below the springing, was copied, in this particular, in other churches and buildings of the district.

The central tower, aisles, W. porch and N.E. transept of Hereford Cathedral are good examples of early 14th-century work, and the chapter-house, now ruined, was built 1359–70. Other notable work of the period is to be found at Madley (chancel, crypt and S. chapel).

Work of the 15th and early 16th century is poorly represented, save by the outer N. porch and the Audley Chapel at the Cathedral.

There is little post-Reformation ecclesiastical building in the district, but the restoration of Abbey Dore and the addition of the tower date from 1633, and there is a much altered chapel at Rotherwas built probably c. 1589 and a tower at Bacton of c. 1573.

Stone vaulting, save in the Cathedral and Dore Abbey, is unusual, but examples occur at Kilpeck (apse), Madley (crypt), Sellack (N. chapel), and Ballingham (S. porch). Stone spires of simple form are to be found at Hereford All Saints and St. Peter's, Peterchurch, Sellack and Goodrich.

Timber roofs of interest survive at All Saints, Hereford (hammer-beam), the cloister of the Vicar's Choral, Hereford, with rich carving, at Rotherwas chapel, a hammer-beam roof of c. 1589, a series of roofs at Abbey Dore erected in the 17th century, and a remarkable roof at Vowchurch built c. 1613 on posts within the walls.

Monastic and Collegiate Buildings.

The cathedral-church of Hereford was served by a college of secular canons, and of this establishment there remains a cloister, called the Bishop's cloister, the ruined chapter-house, the college of the Vicar's choral, a cloister connecting this building with the church and perhaps some slight remains of other buildings.

There were Benedictine cells at Hereford St. Guthlac, Ewyas Harold and Kilpeck attached to the abbeys of Gloucester and Reading, but there are no recognisable remains of any of these. The Cluniac priory at Clifford has very slight remains, but the Grandmontine Priory of Craswall has preserved the whole lay-out of its church and claustral buildings in a very ruined state; it is in every way typical of the planning and arrangement of this little-known order.

The Cistercian Abbey of Dore retains the whole of the crossing and eastern arm of the church, restored to use in the 17th century, and also some remains of the nave and polygonal chapter-house. The latter closely resembles the chapter-house at Margam, the two being the only examples, so far discovered, of this form of chapter-house in the Cistercian order.

The Canons Regular of St. Augustine were represented only by the small priory at Flanesford (Goodrich) of which one rather puzzling building is still standing. The church of the Augustinian Nuns at Aconbury is now the parish church.

The Templars had a Preceptory at Garway which passed in due course to the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. The parish church formerly belonged to this establishment and the foundations of the round nave have recently been uncovered by excavation; a 14th-century pigeon-house also survives. A second preceptory formerly existed at Harewood, but of this there are no recognisable remains.

The Hospital of St. Giles at Hereford had also a circular church, of which the foundations were discovered when the road was widened in 1927. A late 12th-century carved tympanum also survives.

The Knights of St. John of Jerusalem had a house at Hereford which was subsequently transformed into Coningsby's Hospital, part of which dates from the 13th century.

The preaching cross and the western range of the Black Friars' convent at Hereford are still standing, but the building was much altered in the 16th century and is now a ruin. There are no remains of the Grey Friars' house in the western suburb of the city.

Of the numerous almshouses in Hereford, St. Ethelbert's Hospital has been re-built and St. Giles' and Coningsby's Hospitals have already been referred to.

Aubrey's Almshouses (1630) and Price's Almshouses (c. 1665) still preserve their 17th-century buildings.

Secular Buildings.

Mediæval military architecture is well-represented in the county of Hereford, its position on the marches of Wales having necessitated, down to the 15th century, not only an organised system of defence, but also the fortification of all the larger houses on the W. of the Wye. Hereford city was defended by walls which date from the 13th century or earlier and of which there are still some remains; though practically nothing but earthworks is left of the important castle of Hereford. The most extensive surviving castle is Goodrich on the right bank of the Wye; it has a small square late Norman Keep but otherwise is largely a re-construction of c. 1300. There are remains of an early shell-Keep at Kilpeck and a late Norman cylindrical Keep at Longtown. Buildings of the 13th century remain at Clifford and Snodhill (Peterchurch). All the above are strongly defended by earthworks, the two last being of a type which consisted of a very restricted inner enclosure on a high and largely natural hill or mound with a large outer bailey on one side. This type is best represented by Grosmont castle, just over the county boundary in Monmouthshire. A later type of fortress or fortified house is represented by Wilton, Pembridge and Treago which are defended by ditches, angle-towers and curtains. They date, mostly, from the 13th century. Gillow (Hentland) is a fortified manor-house of the 15th century and Kentchurch Court retains a defensive tower.

The earliest surviving house in the district is the Bishop's Palace at Hereford. This is a highly remarkable timber structure with arcades and aisles, built in the second half of the 12th century. Though much altered and re-built early in the 18th century it is yet one of the most valuable examples of early domestic architecture in the country. The other mediæval timber structures are of two types, the more primitive being distinguished by the use of the crutch-truss, a truss consisting of two curved principals carried down to the ground and supporting a ridge and purlins either resting directly on the principals or built up from them. It is obviously impossible to date exactly any given example of this type as it was in continuous use from the earliest times down to the close of the middle ages, if not beyond, and has no distinctive details. The second and more advanced type is distinguished by the extensive use of a bold cusping between the main timbers of the roof and framing; this form is 14th-century in character but appears to have survived in the county well into the 15th century. There are good examples of the crutch-truss at Oldcourt and Ty Mawr, Longtown, Great Treaddow, Hentland, a cottage at St. Martin's, Hereford, and several barns including that at Daren Farm, Llanveynoe, and of the second type at Wellbrook Manor, Peterchurch, and Old Court, Bredwardine.

This second type is often provided with a special form of truss, called a spere-truss, which was incorporated with the structure of the screen. Its distinctive feature is the carrying down of two posts a short distance away from the side walls.

There are elaborate late mediæval roofs at 29, Castle Street and at Booth Hall, Hereford.

There is a 13th-century vault at 89, Eign Street, Hereford, and 14th or 15th-century stone houses at Old Court and Ty Mawr, Longtown, Olchon Court, Llanveynoe, Court Farm, Rowlstone and Upper Goytre, Walterstone.

The larger type of country-house of the 16th and 17th centuries is best represented at Caradoc Court, Sellack; the Mynde, Much Dewchurch and Pontrilas Court, Kentchurch. Holme Lacy is an example of a large mansion of the end of the period. The most notable of the smaller buildings of the period are the Old House, Butchers' Row, Hereford, built in 1621 and ascribed to John Abel, the New House, Goodrich, built in 1636 by the Rev. Thomas Swift on a symmetrical three-winged plan, Huntsham Court, in the same parish, built c. 1620–30, and Old Court, Whitchurch; Langstone Court, Bernithan Court and Ruxton Court, all in Llangarren, have each features of interest.

The river Wye was crossed, in the middle ages, by two bridges only, within the county, a stone bridge at Hereford, which still exists, and a timber bridge at Ross, which was replaced by the present stone structure in 1595. Wye Bridge at Hereford is now a structure of various dates from the 14th century onwards, but Wilton Bridge at Ross survives much as it was built. Both structures, however, were breached during the civil war and subsequently repaired. The only other bridges included in the volume are those at Treago (Sellack) dated 1712, and at Abbey Dore, but a number of undateable structures elsewhere may well be within the Commission's period, though the evidence for their inclusion is lacking.

Fittings.

Altars: Mediæval stone altar-slabs with consecration-crosses, survive at Abbey Dore, Clehonger, Garway, Llangarren, Peterchurch, Urishay, and Vowchurch, and a doubtful example at Llanrothal.

Bells: There are some twenty-five or more bells of Pre-Reformation date: some of these are inaccessible for close inspection, but one at Dulas and another at Llancillo, seen from below, appear to be of the long waisted 13th-century shape, while that at Hereford St. Peter, also narrow waisted and inscribed "Sancta Maria," is probably of early 14th-century date. Two bells at St. Devereux having wheel-stops on the inscriptions may also be ascribed to the 14th century. There are inaccessible bells at Kilpeck, Moccas and Welsh Bicknor which may also prove to be of the 13th or 14th century when examined more closely. A bell at Hentland has the King and Queen head-stops used by the Worcester Foundry and is probably the work of the end of the 14th or beginning of the 15th century. Twelve others with inscriptions in Lombardic capitals are probably of the 15th century. They are at Ballingham, Bridstow, Little Dewchurch, Dewsall, Dorstone, Hereford Cathedral, Llanwarne and Preston on Wye. That at Kenderchurch (inaccessible) may be as ancient. Of the above, two at the Cathedral are inscribed with the names of their founders, William Warwick and Stephen Banister, but their dates and foundries have yet to be identified. Two bells (at Dewsall and Goodrich) have black-letter inscriptions and are probably late 15th-century. Of the above bells one is dedicated to the Holy Trinity (the Warwick bell at the Cathedral), one to God the Father (Dewsall), five to the Blessed Virgin, five to St. John (including the Hentland bell), one to St. Michael (Bridstow), one to St. Gabriel (Llanwarne) and one to St. Cuthbert (the tenor at the Cathedral). The black-letter inscription at Dewsall is a series of letters without meaning. Of the later bells ten dating from 1627 to 1656 can be identified with John Finch the Hereford founder, one by T.H. dated 1627 is at Hentland, three by I. P. are at Goodrich 1672, Bridstow 1675 (re-cast) and Llanrothal 1681, and some twenty are the work of Abraham Rudhall of Gloucester previous to 1714. There are about ten with 17th or early 18th-century inscribed dates but without the names and marks of the Founders. Eight other bell-cotes are inaccessible and the bells cannot be seen from below; some of these may prove to be of earlier date than 1714.

Brasses: The brasses, of any importance, in the S.W. part of the county, are confined to the Cathedral. Here there is a good series beginning with the single fragment from the brass of St. Thomas Cantilupe, c. 1290, and including the fine memorial of Bishop Trilleck, 1360, with a canopy, Canon Richard de la Barre, 1386, in the head of a cross, Richard Delamare, 1435, and his wife with a canopy, Dean Frowsetoure, 1529, with elaborate canopy, and other members of the cathedral body. In addition to the cathedral brasses mention may be made of the curious memorial to a drowned boy at Llandinabo.

Chairs: First in the interest and perhaps unique is the country in the late 12th or early 13th-century chair in Hereford Cathedral; the shallow-turned posts and rails are of a type which survived until the 16th century, but fortunately the details of the arcading are distinctive of the date here assigned to it. There is a somewhat similar chair, assigned to the same period, at Rusby, Sweden. At Dulas is a remarkable collection of fourteen chairs of the first half of the 17th century. There is a rich example of the same period at Hentland and a good late 17th-century example at Michaelchurch Escley.

Chests: There are 'dug-out' chests at Garway, Kingstone, Llancillo and St. Weonards, which date from the 13th or 14th century. Of late 13th or early 14th-century date are the two fine chests with chip-carving in Hereford Cathedral and All Saints, Hereford. Other chests of interest are to be found at Garway, Sellack and Clodock, the last dated 1691.

Churchyard and Wayside Crosses: Herefordshire has retained an unusually large number of churchyard crosses mostly lacking the head and part or all of the shaft. The base-stone commonly has a shallow niche cut in the W. face, but the purpose to which it was put is uncertain. The churchyard crosses at Hentland, Madley and Tyberton retain their carved heads. Many crossshafts have subsequently been used as supports for sundials. The finest wayside cross is that erected by Bishop Charlton (1361–70) to the W. of Hereford City and called the White Cross. The wayside cross at Madley may also be mentioned. In a class by itself is the preaching cross of the Blackfriars at Hereford. This feature formed a common if not invariable adjunct of the lay cemetery of a Dominican convent, but the example at Hereford appears to be the only one which has survived.

Coffin Lids: These are unusually numerous in Herefordshire, but the great majority are of ordinary type. At Llanveynoe are two very early slabs which will be referred to under monuments. At Hereford Cathedral is a richly ornamented coffin-lid of early 14th-century date and a lid of a rather earlier period, at Kingstone, bears a shield with a coat-of-arms.

Communion Tables: Few of these are of any particular interest, but there is a fine early 17th-century example in All Saints, Hereford, and others of less interest at Holme Lacy and Preston on Wye.

Doors: A door on the N. side of the church at Abbey Dore has interesting ironwork of the 13th century and there are remains of ironwork of the same age at Madley. At Bridstow is a door with 14th-century tracery in the head, and in the Audley Chantry at the Cathedral is a panelled and painted door of the 15th century.

Fireplaces: The earliest fireplace, noted in the inventory, is that in the keep at Kilpeck which maybe of late 12th-century date. There are several examples with stone hoods of c. 1300 in Goodrich Castle and a reconstructed 14th-century fireplace of stone in Wellbrook Manor, Peterchurch, and another fireplace of the same period at Flanesford Priory. Later fireplaces are generally of no particular interest and there are no outstanding examples of Elizabethan or Jacobean overmantels. The overmantels at Cobhall Farm, Allensmore; the Mynde, Much Dewchurch; Dewsall Court; and the Black Lion Hotel and 33, Bridge Street, Hereford, may however be mentioned.

Fonts: The most interesting local type of font is of late 12th or early 13th-century date and consists of a very massive bowl of ovolo section made of a variety of breccia; there are examples at Kilpeck, Madley, Bredwardine and Turnastone. There is a richly carved but restored 12th-century font in Hereford Cathedral; there are other fonts of the same age at Michaelchurch, Much Dewchurch and Vowchurch and a very primitive example at Kingstone. The later fonts are of no great interest, but one at Bolstone, with rose, thistle and fleur-de-lis, is probably of early 17th-century date; a second at Thruxton, and a third with cherub-heads and drapery at Holme Lacy, deserve notice.

Galleries: On the S. side of the presbytery at Hereford Cathedral is an early 14th-century gallery with an arcaded screen towards the aisle; it may once have supported the quire-organ. There are early to mid 17th-century west galleries, more or less enriched, at Abbey Dore, Kilpeck and Sellack and a similar gallery of c. 1700 at Clodock.

Glass: S.W. Herefordshire is fairly rich in examples of ancient painted glass. The earliest and most interesting examples are the early 13th-century medallions with incidents from the life of St. John the Evangelist at Madley. In the Lady Chapel at the Cathedral are two windows of late 13th-century glass, one having panels with figure-subjects from the Passion. There are parts of a 14th-century tree of Jesse in Madley church, but more remarkable is the almost complete E. window in Eaton Bishop church which, from its inscriptions, may be dated about 1330. A fair amount of early 14th-century glass also survives in Hereford Cathedral in a rather fragmentary state, and there are fine examples of tabernacle-work, remaining in situ, in Moccas church. Fragmentary work of the same period may be mentioned at Allensmore and Clehonger. There is some much restored early 16th-century glass at St. Weonards. The E. windows at Abbey Dore are filled with 17th-century glass, with figures of apostles, which is remarkable for its colour and quality; it was no doubt put in by John Lord Scudamore about 1633. Some similar glass, with earlier work, fills the E. window at Sellack and was placed there by Richard Scudamore in 1630. It is remarkable that this window with all its incongruities was copied in 1675 in the E. window of the neighbouring church of Foy; the poor quality of the later work shows the decay in the art during the intervening 45 years. Heraldic glass may be noticed at Moccas, Allensmore, Hereford Cathedral, St. Weonards, Clehonger and elsewhere.

Monuments: The earliest surviving funeral monuments in the district are the two primitive slabs at Llanveynoe, one bearing a crucifix, which date from the 11th century. There is also a coffin-lid at Kenderchurch which dates from the 12th century or earlier. The county is prolific in mediæval recumbent effigies; over 50 have been noted in the district under review. Of these 30 are in the Cathedral at Hereford and include the painted figure of Bishop Aquablanca, 1268, Joan Bohun and Peter Grandison in the Lady Chapel, Sir R. Pembridge in the nave, Bishops Stanbery and Mayhew in the presbytery and Bishop Booth in the N. aisle of the nave. As at Wells, a series of effigies, ten in number, were carved about 1300, to represent some of the earlier bishops of the See who were without memorials. The figures are crudely cut and are of little historical interest. Two 14th-century effigies, ascribed to Dean Aquablanca and a Swinefield, are remarkable for the delicate and distinctive treatment of the drapery. Besides the two military effigies mentioned above there are armed figures at Abbey Dore, Bredwardine and Moccas. Priests are represented at Clifford and there is a diminutive effigy of a bishop at Abbey Dore, perhaps indicating a heart-burial. The lady at Welsh Bicknor is a beautiful example of sculpture. Most of the other effigies are local works, crudely rendered in low relief. The priest at Clifford is executed in oak, and the effigies of Bishop Stanbery and Sir R. Pembridge in the Cathedral and one of the Knights at Bredwardine in alabaster.

There are interesting mediæval monuments without figures at Bridstow and Goodrich, both in the form of shrine-bases; these may be compared with the magnificent base of the Cantilupe shrine in the Cathedral. There are slabs with incised effigies at Allensmore (late 14th-century), Hereford Cathedral (1497) and Turnastone (1522).

The series of Renaissance monuments begins with the fine alabaster altar-tombs with effigies of Alexander Denton (1566) in the Cathedral and of John Scudamore, 1571, at Holme Lacy. A rather later (1574) and much shattered monument at Madley should also be noticed; this tomb bears the name of the maker John Gildo. At Bacton, a crudely executed monument commemorates Blanche Parry, maid of honour to Queen Elizabeth and has a figure of the queen herself. In the Cathedral are the remains of a series of monuments of early 17th-century bishops, broken up by Wyatt and others early in the last century. Other late 16th and 17th-century monuments of interest are to be found at Much Dewchurch and Kentchurch. A local type of wall-monument is best exemplified at Foy (two examples 1673 and 1675) and Turnastone (1685). The finest monuments of this period, however, are the two on the N. side of the chancel at Holme Lacy.

Two floor-slabs at St. Devereux have unusual enrichments.

Paintings: There are comparatively few wall-paintings in the district, but of these the large panel of Christ surrounded by implements of labour, at Michaelchurch Escley, is remarkable. At the Cathedral are some much defaced remains of 14th-century figure-subjects in the N.E. transept and a series of apostles and saints on the screen of the Audley chapel. There are also remains of mediæval painted decoration on the walls of Michaelchurch and traces of a Doom at Madley. At Abbey Dore, the transept and crossing has remains of two schemes of decoration dating from the 17th century and the reign of Queen Anne.

Painted decoration in houses is best represented at Caradoc Court, Sellack, and there are remains of a series of painted busts of the Muses, etc., at 133, St. Owen Street, Hereford.

Plasterwork: The district is comparatively rich in examples of ornamental internal plasterwork of the 16th and 17th centuries. Plaster ceilings are particularly numerous in the city of Hereford where the examples at 23, Church Street and the Conservative Club may be specially noted. In the country-districts the most important examples are at Langstone Court, Llangarren, Grange Farm, Abbey Dore, Michaelchurch Court, Michaelchurch Escley. Late 17th-century plasterwork is well represented by the fine series of ceilings at Holme Lacy.

Plate: The most remarkable piece of plate in the district is the 15th-century chalice and paten at Bacton. There are coffin-chalices at Dorstone and Hereford Cathedral; the two at the latter place are of importance as having been taken from the graves of Chancellor Swinefield, 1297, and Bishop Swinefield, 1316. Of the twelve Elizabethan cups three are of 1571 and six date probably from 1576. Later plate of some interest includes a beaker cup at Allensmore, a cup of 1617 at Goodrich, given by Dean Swift, two porringers of 1682 and 1683 at Newton and Wormbridge, a Commonwealth cup of 1656 at Foy and a cup of 1689 at Welsh Newton engraved with Chinese figures. At the Cathedral are two 17th-century maces and at Vowchurch is a remarkable 17th-century wooden cup with figures of birds on the bowl.

Pulpits: Good Jacobean pulpits with their sounding-boards survive at the Cathedral, All Saints, Hereford, Abbey Dore and Sellack; that at All Saints has rich carved ornament. Other pulpits, of the same period, may be mentioned, at Llancillo, Allensmore and Foy. There is a pulpit and sounding-board of c. 1700 at Clodock.

Screens: St. Margarets retains its late 15th or early 16th-century rood-screen, complete with loft and with richly carved bands of ornament. There is a second screen with a loft of about the same date at Kenderchurch, but this has been much restored. The early 16th-century screen at Llandinabo has interesting early Renaissance carving. There are good early 16th-century parclose-screens at St. Weonards. Welsh Newton has a stone screen, of three moulded arches and of c. 1330. Post-Reformation work of this class is represented by the magnificent screen of c. 1630 at Abbey Dore, and by one dated 1613 at Vowchurch.

Staircases: Apart from those of stone there are few if any staircases of importance in the district, dating from earlier than the 17th century. There is an example with early 17th-century turned balusters at New House, Much Dewchurch and others with flat or pilaster-balusters at Gillow Manor, Hentland, Kilpeck Court, Langstone Court, Llangarren and at White House, St. Margarets. Later 17th-century staircases may be noted at Snodhill, Peterchurch; New Court, Marstow; No. 24, Church Street, and No. 29, Castle Street, Hereford; Langstone Court and Bernithan Court, Llangarren and Holme Lacy House. There are early 18th-century staircases of note at the Mynde, Much Dewchurch, and elsewhere.

Stalls: The 14th-century stalls in the Cathedral, though rearranged and reduced in number, are fine examples of the period, with canopies and carved misericordes; forming part of the S. range is the bishop's throne, of the same date, with a lofty canopy. At All Saints, in the city, are stalls of a similar character, with carved misericordes. St. Peter's, Hereford, has 15th-century stalls with a continuous canopy. There are also some remains of the stalls at Madley and Holme Lacy.

Miscellanea: A few important fittings of unusual character may be collected under this heading. Of these the most important are the remarkable swinging iron screens at Rowlstone. Their position shows that they had some connection with the lenten veil but the cross-bars are provided with pricks and rings for candles. The animal-ornament is peculiar and the whole is a perhaps unique survival in this country. At Kilpeck is a holy-water stoup of the date of the church (12th-century) with a crude carving of a figure clasping the bowl; stoups of this age are extremely rare. Bacton preserves an embroidered altar-frontal of the age of Elizabeth and said to have been worked by Blanche Parry, one of her Maids of honour. In the N. aisle at Madley is a large family pew, made up with earlier screen-work and roofed in.