Pages xxi-xxxiv

An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, Volume 1, North West. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1916.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

NORTH-WEST ESSEX.

Sectional Preface.

(i.) Earthworks, etc., Prehistoric and later.

North-west Essex is not rich in prehistoric earthworks. Such as there were, the plough has long destroyed. Only two hill-forts survive, one on Ring Hill, in Littlebury parish (see Plan, p. 193), the other on a hill near Saffron Walden. The work on Ring Hill is large (16½ acres), and although the defences are in places denuded, the complete outline remains. The work near Saffron Walden, which is not shown on the Ordnance Survey maps, is in a fragmentary condition.

Earthworks of the historic period, to be mentioned below in their proper places, are more common. There are six castle sites. The most noteworthy is at Clavering, which there is some reason to connect with a pre-Conquest castle (see Plan, p. 67). The earthworks at Castle Hedingham (see Plan, p. 48) and Stansted Mountfitchet (see Plan, p. 275) are well preserved and noteworthy; of those at Great Easton, Rickling and Saffron Walden little remains. Fortified mounts occur at Berden, Chrishall, Elmdon and Stebbing, and some of them, at one time, may have had one or more attached courts, which have since been totally destroyed. Many farmhouses are moated; many mill-mounds and dams are scattered about the district. At Saffron Walden there survives the western part of a large oblong enclosure, Repell or Battle Ditches, defended by a rampart and ditch. Its origin and use are uncertain; a Saxon cemetery and traces of prehistoric occupation were found on the site (see Plan, p. 259). Saffron Walden, too, possesses a maze, cut in the turf on the Common; it has been re-cut on several occasions and dates back at least to the 17th century (see Plan, p. 260).

(ii.) Roman Remains.

The north-west corner of Essex, like the adjacent parts of Cambridgeshire and Suffolk, was fairly populous in Roman times. All three districts contain, indeed, much excellent cornland; it is easily credible that they provided a share of the grain which Britain is known to have exported in the fourth century to the opposite mainland, and, in especial, to the Roman armies guarding the lower Rhine.

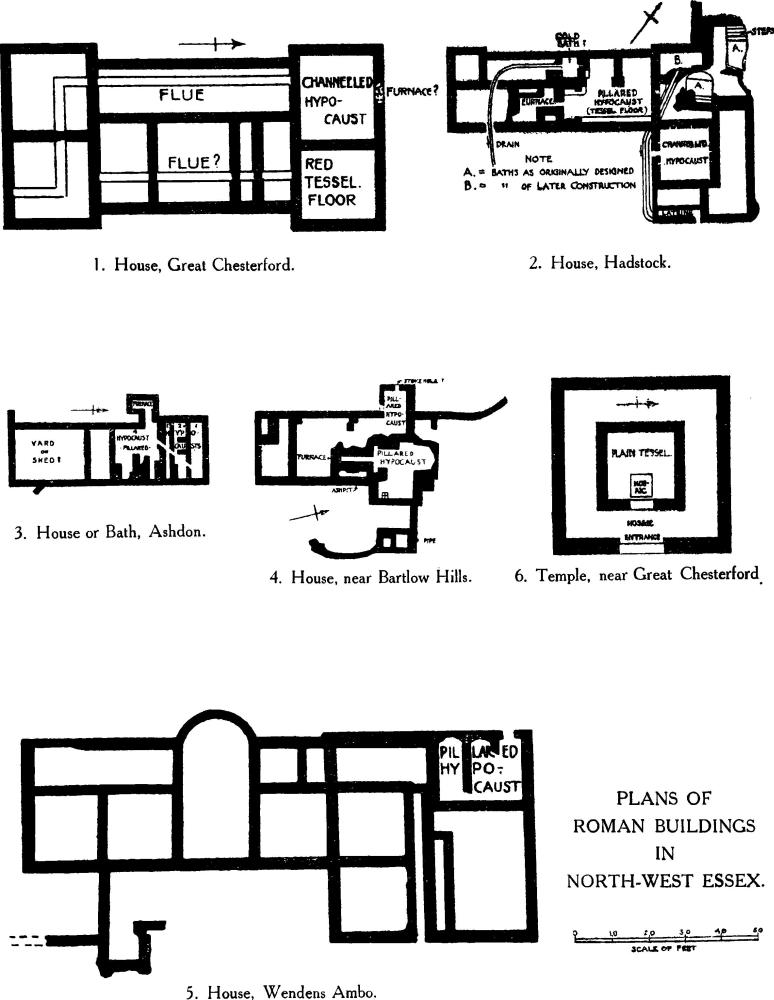

Plans of Roman Buildings in North-West Essex.

The Roman structural remains in north-west Essex, which indicate civilized habitation, consist of a small town or village at Great Chesterford, a country-house or farm of considerable size at Ridgewell, and smaller rural dwellings, doubtless farms, in the parishes of Ashdon, Hadstock, Stansted Mountfitchet, Thaxted and Wendens Ambo. The Bartlow Hills are remarkable burial-mounds (see Plan, p. 4), with a small dwelling-house close to them (across the Cambridgeshire border); Ashdon parish has also yielded a well-built tile-kiln. In addition to the certain sites, there are somewhat unsatisfactory records of discoveries at Steeple Bumpstead and Littlebury, while tiles, plainly taken from Roman structures not very far away, have been noted at Little Dunmow, and in the walls of churches at Broxted, Bulmer, Great Easton, Gestingthorpe, Takeley, and possibly at Elsenham and elsewhere. (fn. n1) On the other hand no traces exist of military occupation. Roman north-west Essex may then be thought of as a peaceful, well-populated, corn-growing district, and the inhabitants as sufficiently Romanized for the more or less prosperous among them to dwell in houses built and furnished in Roman fashion. It may be worth while to add the details of the occupation.

Town or village:—The fields on the north-west side of Great Chesterford village, towards the river Granta, have yielded numerous traces of Romano-British town or village life. There seems to have been a roughly oblong enclosure of perhaps 35 acres, surrounded by a strong wall. The wall is recorded to have been 12 feet thick and constructed of stone, rubble and cement, and bonded with courses of tiles; it was destroyed in the course of the 18th century for road-metal, and its course was not at all certain by about 1775; nothing now survives of it above ground. Within the northern part of the enclosure a dwelling-house was noted in 1719 by Stukeley (who miscalled it a temple); it was excavated in 1848 by the Hon. R. C. Neville, afterwards fourth Lord Braybrooke. It was a small 'corridor-house' (49 feet by 102 feet) with corridor and three rooms in the middle and two rooms in each wing; in the north-west wing one of the rooms had a tessellated floor, and the other was fitted with a hypocaust, but the exact system of heating does not seem to have been made out (see Plan, 1). Painted stucco from the walls of the rooms and a dwarf pillar, probably from the corridor, were proofs of decoration; doubtless the whole formed a fairly comfortable dwelling-house. After the excavation, the foundations were removed, and even the site is not exactly known. (fn. n2) The only other remains of building definitely recorded on the site is a tessellated pavement, noticed near the mill, that is, in the south end of the walled area or even outside it; besides, an amphitheatre has been conjectured, a little rashly, from foundation marks in the fields near the river, and remains, apparently of a lime-kiln, were encountered in 1880. On the other hand, small finds have been many. A large part of the site was used as a parish gravel pit from about 1750 until a few years ago, and many pits, wells, and the like have been cleared out; the pottery, metal objects, coins, etc., preserved by Lord Braybrooke at Audley End, indicate a long occupation and a Romanized population. The Roman name of the place is unknown; Iciani, suggested by Horsley in 1725, and still admitted to some maps, is almost certainly wrong.

With this site may be connected (a) a neighbouring 'villa,' dug out by the Hon. R. C. Neville in Ickleton parish, Cambridgeshire, on the west bank of the Granta, and, (b) a mile E. of Chesterford, a small temple of the 'Celtic' type, which was laid bare by the same antiquary in 1847, and was miscalled by him a dwelling-house (see Plan, 6). (Neville, Sepulchra Exposita. Saffron Waldon, 1848, p. 89).

Farms and country-houses.—At Ridgewell, on a hillside sloping to the Colne, part of a 'courtyard-house' was uncovered in 1794. The plan then made shows a fairly extensive building round a courtyard, (120 feet by 200 feet); it had hypocausts, an elaborate mosaic floor, and several tessellated floors, painted wall-plaster, window-glass, etc. Other foundations not explored may belong to outbuildings. In the next field to the west, a pavement of stone flags has been noticed, and there is a good spring of water. An old road, thought to be Roman, can be traced running E. and W. between the house and the river (Archæologia xiv. 61–74). Plainly there stood, on the site indicated, a fairly large and comfortable dwelling; coins show that it was occupied during most of the Roman period down to its end. Nothing is now visible, but the site is locally known, and is marked (as it seems, correctly) on the Ordnance Survey maps.

Four small houses have been dug up and planned in the parishes of Ashdon, Hadstock, Wendens Ambo, and near the Bartlow Hills. Three of them contain little beyond apartments for heating or bathing. Similar small houses have been found elsewhere in southern Britain; it is conceivable that they originally included rooms built in wood or clay, which have now vanished, besides the stone-built rooms intended for fires and heating, which have alone survived.

The house at Great Bowser's Farm, in Ashdon parish, excavated in 1852, was a small block (17 feet by 52 feet), of which the northern half (see Plan, 3) was heated from a furnace, while two southern rooms were outbuildings or yards; trenching showed no traces of stone foundations round it (Archæological Journal, x, 1853, pp. 14–17). The Bartlow house, excavated—perhaps not fully— in 1853, was similar. The block (43 feet by 48 feet) contained in the northern half two heated rooms and their furnaces; the southern half was rougher and less habitable (see Plan, 4). The floors of the rooms were simple, and the walls were adorned with the usual stucco. An adjacent structure contained two small tanks, possibly for drinking purposes, for washing wool or the like. Coins found in what seemed to be the ash-pit indicated a long occupation, ending about A.D. 350 (Archæological Journal, x, 17). The dwelling house in Sunken Church Field, close to the Granta, in the north part of Hadstock parish, was a block of 60 feet by 85 feet, and contained hypocausts with bathrooms at the north end and less substantial structures, or yards, at the south end; three bathrooms were traceable, but one of them had been built in place of another (see Plan, 2). The small finds comprised pottery of late 2nd-century date and coins of A.D. 250–370 (see Archæological Journal, viii, pp. 27–35). The fourth of the planned houses, at Wendens Ambo, uncovered in 1853, was larger than the others (60 feet by 135 feet) (see Plan, 5); unfortunately the records are not altogether clear; it had apparently only one hypocaust (see Archæological Journal, xi, 77).

Burials:—The large tumuli called the Bartlow Hills are perhaps the best examples in Britain of a mode of mound-burial which seems to have obtained among the native population on both sides of the sea, in East Anglia and in Belgium, and to have lasted on into Roman days. According to this method, the burnt bones of the dead were placed with costly grave-furniture in a small stone-built chamber or cist, and covered with a mound of earth, many feet high and broad. The 'Hills' at Bartlow were opened in 1832–40 and yielded fine pieces of Roman bronze, glass and enamel, and one coin, of Hadrian. These objects were mostly preserved at Easton Lodge, and destroyed in a fire there in 1847, but they are known from careful drawings and illustrations. They seem to date from the end of the first and the beginning of the second centuries, and the graves may be assigned to wealthy Romanized British chiefs or landowners of the neighbourhood. (fn. n3)

Roads:—The Roman roads of north-west Essex are as yet imperfectly understood, and can hardly be treated except in connection with those of the whole county. It may suffice to indicate the main outlines:—(1) A road, of which traces can be seen in old lanes near Strethall and Morley Green, ran north-east from Braughing in Herts to Great Chesterford and beyond; the northern part is preserved in the high road which still runs north-east from Stump Cross, just outside Great Chesterford. (2) Another road, almost wholly preserved in modern highways, ran east from Braughing through Bishop's Stortford to Great Dunmow, Braintree, Coggeshall, and finally Colchester; it was called Stane Street as early as 1277. In its western section, with which alone this volume is concerned, it passes through a country curiously empty of recorded Roman sites. (3) The Roman road from Colchester to Cambridge must have crossed north-west Essex. Its line, however, is so little known that no remark can be made on it at present; a fragment of ancient road noted near the Roman house at Ridgewell has been conjecturally connected with it (Arch. xiv, 68).

(4) It remains to notice two puzzling roads, seven miles apart, which run today north-eastwards across the area with which this volume is concerned. They are remarkable for their straightness, and still more remarkable because they run precisely parallel in a direction 25°–26° E. of N. One road, sometimes called Suffolk Way, runs straight for four miles from the district called the Rodings towards Great Dunmow; the long village of High Roding has plainly grown up on each side of it. It seems to continue, though less clearly and directly, through Great Bardfield and Finchingfield towards Clare in Suffolk. The other road begins at Little Waltham, north of Chelmsford, and runs straight for twelve miles through Braintree towards Gosfield, where (as a straight road) it vanishes. Some explanation is required both of the straightness and of the parallelism of these roads. They do not begin or end at places connected (so far as is known) with Roman inhabited sites or with other Roman roads. They do not pass through any important Roman sites. They are, however, old roads. Both appear with their present courses on the map of Essex drawn by Hans Woutneel in 1602 and on other maps of the next 100 years, and that alone suffices to show that they are not attempts of the late seventeenth or eighteenth century to straighten important coach-routes. It is possible that they are a piece of Roman 'centuriation' or land-surveying, applied by the government to the province of Britain or at least to the 'territorium' of the neighbouring municipality of Colchester. Such territories normally belonged to Roman municipalities, whether in Italy or the provinces, and many examples of them could be quoted. In Britain no vestige—or at least nothing that can be called a really probable vestige—has yet been noted elsewhere, and further proof is desirable in this case. But the theory would explain the absence of Roman sites along the roads, and deserves to be borne in mind, as a possibility.

(F. Haverfield.)

(iii.) Ecclesiastical and Secular Architecture.

Building materials; stone, flint, brick, etc.

Most of the ecclesiastical buildings in north-west Essex are constructed of flint or pebble rubble with much mortar. The late 11th and early 12th-century rubble is commonly more or less evenly coursed, and in several churches of the same date, such as those at Wendens Ambo, Stambourne and Birdbrook, Roman bricks are sparingly used as dressings or are laid herring-bone-wise in the walls. The external stone dressings are of limestone in the earlier work; in the later work, both for internal and external purposes, clunch is almost exclusively used. The extensive use of brickwork began late in the 15th century; several churches have towers entirely built of that material, and there is a brick chancel at Langley church. Timber-framing was little used in churches, but a good example of a timber-framed porch occurs at Radwinter. Towers were sometimes relieved by internal timber-framing from the ground floor to the bell-chamber, as at Wethersfield.

Domestic buildings differ widely. Among those of pre-Reformation date, only two have any part built of stone. They are the Kitchen wing at Little Chesterford Manor-house, and the main block at Prior's Hall, Widdington. Otherwise, the universal material is timber-framing, filled, and generally covered wholly, with plaster, but a small proportion of buildings still have the timber exposed. A few early 16th-century houses, such as Rickling Hall, Rickling, and part of St. Aylotts, Saffron Walden, are built of brick. The early brick buildings generally have dressings of the same material, often plastered in imitation of masonry. The later 16th-century and the 17th-century houses are mostly timber-framed, with brick chimneystacks; many of the more important buildings, such as Moyns Park, Steeple Bumpstead, Spains Hall, Finchingfield, Berden Hall, Berden, and Clock House, Great Dunmow, are mainly or entirely of brick. At Audley End, Saffron Walden, the whole house is faced with ashlar.

Such methods of construction are common to all north-west Essex. The only feature peculiar to any one part of it is the brick church-tower, which is (with the exception of Ugley Church) only to be found in the eastern half of the district.

Of the surviving military buildings, the ruins of the castles of Stansted Mountfitchet and Saffron Walden are of flint rubble, while the great keep at Castle Hedingham is faced with Barnack-stone ashlar.

Ecclesiastical Buildings.

Only three churches in north-west Essex, those at Thaxted (Plates, pp. 302, 305), Saffron Walden (Plates, pp. 229, 231) and Castle Hedingham (Plates, pp. 47, 49), exhibit great architectural excellence.

1. If the churches are examined chronologically, it will be found that the proportion of early work is unusually large. Four churches, those at Chickney, Hadstock, Little Bardfield (Plate, p. 171) and Strethall (Plates, pp. 295, 296), contain work which may be definitely dated as belonging to the earlier half of the 11th century, that is, before the Conquest, and the same is probably true of Sturmer (Plate, p. xxviii) and Wethersfield. At Chickney, the Saxon nave and chancel are both standing. Hadstock has the remains of a remarkable cruciform church, which may possibly be the 'minster' erected in 1020 by Canute to commemorate his victory over Edmund Ironside at Ashendon; the detail of the N. doorway and transeptarches is perhaps unique (Plates, pp. xxviii, 144). At Little Bardfield the church has a massive W. tower of pre-Conquest date (Plate, p. 171). Strethall church shews a well preserved chancel-arch and a S. doorway, both of early 11th-century date (Plates, pp. 295, 296).

Of early post-Conquest work, the towers at Stambourne (Plate, p. 272) and Steeple Bumpstead are both probably of the 11th century. Castle Hedingham provides a fairly complete example of a late 12th-century parish church on an ambitious scale (Plates, pp. xxviii, 47, 49); Elsenham and Great Easton churches, and the desecrated chapel at Wicken Bonhunt (Plate, p. 342) are more or less complete but smaller buildings of the same century. Other good examples of 12th-century work are the N. and S. doorways and chancel-arch at Stansted Mountfitchet (Plate, p. xxviii), the W. doorway at Birchanger, the S. doorways at Belchamp Otton and Littlebury (Plate, p. 191), the towers at Finchingfield (Plate, p. 89) and Wethersfield, and the remaining arcade at Little Dunmow Priory church (Plate, p. 177).

The 13th century is poorly represented. The chancel at Birdbrook is perhaps the best example of that date; the nave at Tilty is plain but interesting, and there is good detail at Berden and Widdington. The late 13th-century crypt at Saffron Walden is the only example of stone vaulting of that period.

Stebbing, Shalford and Bardfield Saling have fairly complete churches of the 14th century; the Lady Chapel (now the parish church) at Little Dunmow, and the chancel at Tilty are rich examples of monastic work. Good detail of the same period also occurs at Great Sampford (Plate, p. 136), and the nave-arcades at Thaxted (Plate, p. 305), the N. arcade at Henham (Plate, p. xxxii), and the arcade (re-cut) at Little Maplestead are worthy of note.

The churches of Saffron Walden (Plate, p. 229), Thaxted (Plate, p. 302), Bocking and Clavering are almost entirely of the 15th or early 16th century; the first two are unusually handsome examples of the East Anglian type of the large town church. The towers of Great Dunmow and Great Yeldham are also effective works of the same period. The north-eastern part of the district under review contains four early 16th-century brick towers—at Gestingthorpe (Plate, p. 99), Liston, Tilbury-juxta-Clare and Wickham St. Paul—all of the same character; a fifth, more ornate, occurs at Rayne (Plate, p. 218) and Ugley, in the western part of the district, adds an isolated sixth example. At Castle Hedingham is a brick tower, dated 1616, and those at Stansted Mountfitchet and Toppesfield are dated respectively 1692 and 1699.

2. Apsidal E. ends appear in three churches, at Great Maplestead and Pentlow (Plate, p. 208), of the 12th century, and at Little Maplestead of the 14th century. Evidence has also been found of a now vanished apsidal chancel, of early 12th-century date, at Castle Hedingham.

At Pentlow and Bardfield Saling round towers are still standing; at Arkesden and Birchanger similar towers are said to have been destroyed during the 18th century. The 'round' nave at Little Maplestead (Plate, p. 184) is one of the five of that type which still stand in England. None of the churches has a central tower, but there is architectural or documentary evidence of two, now vanished, at Debden and Great Easton, and others may also have stood at Hadstock, Saffron Walden and Thaxted.

Fourteen churches have 'low-side' windows; not one of them retains the original shutter.

The roofs of the S. chapel at Ashdon, and the S. transept at Thaxted are good examples of 14th-century work; the roof of the S. porch at Debden, of the same period, is elaborately moulded. The best examples of 15th and early 16th-century roofs are those of the chancel at Bulmer and of the naves at Langley, Newport and Saffron Walden, and the greater part of the church at Thaxted (Plate, p. 305). The early 16th-century roofs of the naves at Castle Hedingham (Plate, p. 49) and Gestingthorpe (Plate, p. 100) and the roof of the S. aisle at Steeple Bumpstead are very ornate and are all probably due to the same carpenter, Thomas Loveday, of Castle Hedingham. whose will was dated 1535. His name appears on one of the timbers at Gestingthorpe, and the roof of the N. aisle at Wimbish bears the date 1534 (Plate, p. 349).

Monastic and Collegiate Buildings.

The most important survival of monastic work is the Lady Chapel of the Augustinian Church at Little Dunmow (now the parish church). The main dimensions of the original church have recently been recovered by excavation (see Plan, p. 176). Of the Cistercian Abbey at Tilty the present parish church was probably the capella extra portas; otherwise, the only remains consist of one wall of the cellarer's range. Earthworks alone mark the sites of Thremhall (Stansted Mountfitchet) and Takeley Priories, and a few worked stones those of Berden Priory and Newport Hospital. A fragment of walling is the only trace above ground of the Benedictine Nunnery of Castle Hedingham. Little Maplestead Church was the chapel of a Commandery of the Knights of St. John, but no remains of the domestic buildings have survived.

The Abbey Farm and Almshouse at Audley End form a good example of a large almshouse of early 17th-century date (Plates, pp. xxxiv, 239).

Secular Buildings.

More than two hundred houses of pre-Reformation origin are scheduled in the Inventory; of these, 28 are in Saffron Walden, and 21 in Thaxted. Manor House Farm, at Little Chesterford (see Plan, p. 174) is definitely of the 13th century; Prior's Hall at Widdington may possibly be of equal age. Tiptofts at Wimbish (Plate, p. 351), Great Codham Hall at Wethersfield, and a house (92) in Church Street, Saffron Walden (Plates, pp. 252, 254), retain representative 14th-century work. There are many 15th-century houses, parts of Horham Hall, and the Recorder's House at Thaxted (Plate, p. 313), some houses in Bridge Street (Plate, p. 37) and King's Street (Plate, p. 254), Saffron Walden, a house S. of the church at Clavering (Plate, p. xxvi), Monk's Barn at Newport (Plate, p. 204), are the best instances. The Manor House Farm at Little Chesterford, and Tiptofts, Wimbish (Plate, p. 351), are the only two aisled Halls in the district. The greater part of Horham Hall, Thaxted (Plate, p. 308), is an important building of early 16th-century date, Moyns Park (Plates, pp. 291, 292) at Steeple Bumpstead, Spains Hall (Plate, p. 91) at Finchingfield, Gosfield Hall (Plate, p. 104) at Gosfield, Broadoaks (Plate, p. 353) at Wimbish, Stansted Hall (Plate, p. xxiv) at Halstead, and Doreward's Hall (Plate, p. 34) at Bocking, are all handsome examples of late 16th-century work. Though much restored and also reduced in size, Audley End (Plates, pp. 234, 238, etc,) is still among the finest early 17th-century mansions in the country; and domestic work of the same period on a smaller scale is well exemplified by the Abbey Farm and Almshouses at Audley End (Plate, p. 239), the Clock House at Great Dunmow (Plate, p. 133), Panfield Hall with its tower (Plate, p. 207), the Brick House at Wicken Bonhunt (Plate, p. xxiv), and the Stables of the destroyed Great Lodge at Great Barfield (Plate, p. xxiv). Noteworthy houses of late 17th or early 18th-century date are Quendon Hall at Quendon (Plate, p. xxiv), Saling Hall at Great Saling (1699) (Plate, p. 133), Chrishall Grange at Chrishall, and Shortgrove House at Newport. Good pargetting is rare, but Crown House (1692) at Newport (Plate, p. 203), and the 17th-century plasterwork on a house in Church Street (Plate, p. 254) at Saffron Walden are exceptionally elaborate examples.

The cottage plan is generally of the central chimney type; a considerable number are of the 16th century. The smaller houses of 15th and early 16th-century date are all of the usual mediæval plan, with a central Hall, in many cases originally open to the roof, and Solar and Buttery wings at each end. The Hall has almost invariably been divided into two storeys during the 16th or 17th century.

At Thaxted (Plate, p. 310) and Ashdon are good guild or moot halls of the 15th or early 16th century. The only example of a school building is the so-called moot hall at Steeple Bumpstead (Plate, p. 310); the foundation-charter is dated 1592.

The remains of military architecture are few, but the keep of Castle Hedingham (Frontispiece) is among the most complete structures of its class in England. The shell of another 12th-century keep still stands at Saffron Walden (see Plan, p. 234) and there are fragments of masonry at Stansted Mountfitchet Castle (see Plan, p. 277).

Only two bridges have come within the survey of the Commission—the unusually fine, late 15th or early 16th-century brick bridge over the moat of Hedingham Castle (Plate, p. 57), and the bridge, also of brick, over the moat of Latchleys (Plate, p. 207) at Steeple Bumpstead.

Many of the pre-Reformation houses retain more or less considerable remains of the original roof construction, which is usually of the king-post type and is sometimes—as in the houses specially mentioned above—enriched with mouldings. At a house, formerly a chantry-house, in Halstead, and at Panfield Hall, are remains of hammer-beam roofs of the 15th and 16th centuries, and the roof of that type in the former chapel of the almshouses at Audley End (Plate, p. xxxiv) is a curious example of early 17th-century date.

Fittings.

Altars:—The existing altar-slab at Chickney appears to be the only surviving example, but a slab outside the chancel at Birdbrook may have served that purpose.

Bells:—Thirty-nine bells are of pre-Reformation date. Six of them are of the 14th century; the first, at Strethall, is the work of William Revel (1350–60); the third, at Ridgwell, is by Robert Rider (1357–86); and the bell at Little Sampford bears the name of William Rofford (late 14th century); the remaining three—at Debden, Strethall and Ridgewell—are either uninscribed or of uncertain origin. Of the post-Reformation bells, a large proportion are from the Miles Graye foundry.

Brasses:—Only four brasses are of the 14th century. The earliest and finest is that of Sir John de Wautone, 1347, and his wife, at Wimbish; the two figures are in the head of a cross. Brasses of ecclesiastics are not very numerous, though there are priests in academic dress at Thaxted, (c. 1450), and at Strethall (c. 1480), and at Saffron Walden is a good brass of a priest in mass vestments. Perhaps the most interesting of the class is the brass, at Wenden Lofts, of William Lucas (c. 1460) with his wife and children, amongst whom is John, Abbot of Waltham, in mass vestments. The brass of Sir John de la Pole (c. 1370), at Chrishall, is the finest military figure in the district; the knight and his wife are under a handsome triple canopy. Other good military brasses are those of Bartholomew, Lord Bourchier (1409) with his two wives, at Halstead, and of Henry Bourchier, K.G., and Earl of Essex (1483) with his wife, at Little Easton; the second brass is one of the few showing the full insignia of the Garter, and has remains of enamel. The figures of civilians have no special interest, except that at Gosfield, of Thomas Rolf (1440) in the robes of a Sergeant-at-Law.

Five slabs have indents of early 14th-century crosses and inscriptions, and at Belchamp Walter are two indents of handsome canopied brasses.

Chairs:—Many churches contain 17th-century chairs, often richly carved. Those at Bocking, Great Chesterford, Great Dunmow, Great Yeldham, Radwinter and Stambourne are among the noteworthy examples. At Little Dunmow is the well-known 'Flitch' chair (Plate, p. 307), which appears to be made up of several pieces of 13th-century woodwork.

Chests:—The finest chest in the district under review is the handsome piece of late 13th-century furniture at Newport (Plate, p. 199), with painted figures on the under side of the lid. There are four examples of the 'dug-out' type, all probably of pre-Reformation date. Debden, Rickling and Tilbury-juxta-Clare have fine iron-bound chests, and the two chests at Thaxted, one with cusped and one with linenfold panels, are good examples of the 15th and early 16th century respectively. Jacobean chests are numerous, those at Great Dunmow and Radwinter are the most ornate.

Consecration Crosses:—Consecration Crosses occur externally at Great Sampford, Helion Bumpstead, and possibly also at Great Dunmow, and internally at Bulmer and Toppesfield.

Cupboards:—The cupboard at Great Sampford is a good example of 16th-century joinery.

Doors:—The N. door at Hadstock is possibly contemporary with the doorway (Plate, p. xxviii), a pre-Conquest work of the 11th century; it is quite plain, and traces of human skin have been found on it. The doors at Castle Hedingham are of late 12th-century date, and have original ironwork; they are also remarkable as they are formed of joggled battens. At Bocking the S. door is covered with scrolled ironwork of c. 1260 (Plate, p. 32). There are three 14th-century doors with elaborate traceried panelling, at Finchingfield (Plate, p. 32), Great Bardfield and Shalford. Of later doors the best examples are at Gosfield, Saffron Walden and Thaxted.

Fireplaces:—Fireplaces are generally of 16th-century or later date, but the 12th-century examples at Hedingham Castle are amongst the finest of that period in the country. The fireplace in the chancel of the parish church at Birdbrook is remarkable for its character and position. At Bower Hall, Steeple Bumpstead, is a richly carved fireplace of the 17th century; elaborately enriched overmantels of the same century occur at Audley End (Plate, p. xxxv), in a house in the High Street, Saffron Walden (Plate, p. xxxiv), and at Doreward's Hall, Bocking. An example, probably of slightly earlier date, is at Loft's Hall, Wenden Lofts.

Fonts:—The oldest font in North-west Essex is the rudely ornamented bowl at Little Maplestead, which is probably of the 11th century. At Pentlow (Plate, p. xxx) and Belchamp Walter (Plate, p. xxix) are 12th-century fonts, that at Pentlow being richly but crudely carved. Arkesden (Plate, p. xxix), Chrishall (Plate, p. xxix), and Clavering have undistinguished examples of the 13th century. At Great Sampford (Plate, p. xxix), Little Dunmow and Newport are good 14th-century fonts. Fonts of the 15th century form a relatively large class; that at Chickney (Plate, p. xxix), is richly carved, and those at Bulmer (Plate, p. xxix), Halstead (Plate, p. xxix), and Gestingthorpe (Plate, p. xxix) are the best. At Littlebury (Plate, p. 193) and Thaxted (Plate, p. 304) the fonts are enclosed in rich cases of panelling, which terminate in gabled and pinnacled spires of early 16th-century date. Spire-form covers of tabernacle work also occur at Pentlow (Plate, p. 193) and Takeley ; at Takeley the former font-case now serves as a cupboard.

Gallery:—The late 15th-century gallery in the S. aisle at Great Dunmow (Plate, p. 119), which is connected with the parvise of the S. porch, is curious.

Glass:—The largest survivals of pre-Reformation glass occur in the churches of Clavering, Thaxted and Stambourne, but numerous other churches have examples in smaller quantity. At Lindsell and Newport are 13th-century panels with figures of saints, but the glass at Newport was brought from elsewhere. Good 14th-century figures remain at Thaxted and Great Bardfield, and there is fine heraldic glass of the same period at Shalford, Wimbish, Great Bardfield and Arkesden. Much 15th-century glass, in a somewhat shattered condition, survives at Thaxted and Clavering. In Thaxted church one window represents the story of Adam and Eve and is of unusual type ; at Clavering a window shows the legend of St. Katherine. The upper part of the E. window at Stambourne is filled with early 16th-century heraldic glass, including figures and design of unusual excellence. A panel of late 17th-century glass at Clavering serves as a funeral monument.

Lecterns:—An unusually complete lectern of the 15th century survives at Newport (Plate, p. 199); two others of the same period are at Littlebury and Ridgewell, and the base of a third supports a palpit of later date at Clavering (Plate, p. xxxi). The lectern at Hadstock is a curious example of early 16th-century date.

Monuments:—An early 13th-century effigy carved in low relief, said to exist at Toppesfield, is now covered by the organ. Three military effigies of a later date in the same century occur at Little Easton (Plate, p. xxx), Clavering and Stansted Mountfitchet. At Halstead are two 14th-century monuments (Plate, p. 150), each with effigies of a knight and lady, and a much restored figure of a lady at Chrishall is of late 14th-century date. Of the 15th century, the finest effigies are those of the last Lord Fitzwalter and his wife at Little Dunmow (Plate, p. 178). At the same place is the effigy of a lady, of a somewhat earlier date in the century; at Wethersfield are effigies of a knight and lady of c. 1480 (Plate, p. 333), and the figure of a priest, of the same century (Plate, p. xxx), at Arkesden, is the only ecclesiastical effigy in the district. The finest piece of monumental art in north-west Essex is the 14th-century archway to a tomb-recess or chantry chapel (Plate, p. 20), at Belchamp Walter. Other good examples of pre-Reformation memorials are at Shalford (Plate, p. 262), Little Easton (Plate, p. xxx), Gosfield, and Rickling.

The monument of John de Vere, Earl of Oxford (Plate, p. 50), at Castle Hedingham, and that of Thomas, Lord Audley, at Saffron Walden, are exceptionally rich examples of 16th-century carving ; both have slabs of 'touch,' and are probably of foreign workmanship.

Many Elizabethan and Jacobean monuments occur in the district ; the finest are possibly those at Arkesden, Borley, Great Maplestead (Plates, pp. xxxiv, 130), Little Easton (Plate, p. 182), Pentlow (Plate, p. 210) and Stansted Mountfitchet. The figure of Sir Thomas Middleton, at Stansted, wears the Mayoral chain of the City of London. Clavering and Little Sampford (Plate, p. 187) have good late 17th and early 18th-century memorials.

Stone coffin-lids, mostly of the 13th century, are fairly common. The marble coped slab at Little Dunmow and the 12th-century diapered coffin-lid built in above the doorway at Elsenham are worthy of special note.

Paintings:—Ecclesiastical painting is poorly represented in the district, but traces of figure-subjects remain at Belchamp Walter, little Easton and Tillbury-juxta-Clare, all in a very bad state of preservation. At Tilty are remains of 13th-century painted masonry-lines, and at Belchamp Walter are fragmentary designs of different dates and faint traces of a Wheel of Fortune.

More important are various examples of secular wall-painting of late 16th or early 17th-century date. They represent a class of work possibly more common in Essex than elsewhere. Perhaps the finest instance is the elaborately decorated room at Campions, Sewers End, Saffron Walden; the Rose and Crown Inn at Ashdon has a notable painted room (Plate, p. 8), of simpler character. Traces of painting also occur at Horham Hall, Thaxted, Bradfield's Farm, Toppesfield, and Latchleys, Steeple Bumpstead. The walls of the late 17th or early 18th-century staircase in a house (10) at Clavering are painted with contemporary versions of Scriptural subjects.

Panelling:—The early 16th-century panelling at Gosfield church is of considerable excellence, and many secular buildings contain examples of the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries. The most noticeable are those at Gosfield Hall and Pentlow Hall.

Piscinae:—No piscina is of particular excellence. The 13th-century examples at Chickney, Elsenham and Tilty are worthy of note, and fairly good 14th-century examples exist at Bulmer, Clavering, Great Dunmow, Great Sampford, Little Dunmow, Tilty and Wethersfield. The piscina at Little Dunmow, once richly carved, is now much defaced.

Plate:—The one surviving piece of pre-Reformation plate is the stem and base of a 15th-century chalice at Radwinter. Most of the plate is of the 17th century, but Great Saling has a cup and paten of 1559 ; Hempstead, Strethall and Wethersfield have cups of 1561, seven other churches of 1562, one of 1563, one of 1564, and five others of later dates in the 16th century. At Berden and Gosfield are rich secular Jacobean cups ; the former is pear-shaped. At Great Sampford and Hempstead are repousse dishes of 1630, which are probably also of secular origin. All the marked plate is from the London Assay office.

Pulpits:—Four churches, Henham (Plate, p. xxxi), Rickling (Plate, p. xxxi), Takeley and Wendens Ambo, have panelled pulpits of the 15th century ; that at Takeley retains the 'trumpet' stem. Elizabethan and Jacobean pulpits are common, but few can be called excellent. Those at Bardfield Saling, Broxted (Plate, p. xxxi), Clavering (Plate, p. xxxi) and Great Yeldham, all of early 17th-century date, may be mentioned as worthy of note. At Thaxted is a good late 17th-century pulpit and sounding-board (Plate, p. 307).

Reredos:—Thaxted and Little Dunmow both contain rich examples of the tabernacled reredos, though all the images have been lost. Stebbing has traces of similar work, with remains of colour, but now wholly defaced.

Screens:—The most remarkable screens are the late 14th-century examples in stone incorporated in the chancel-arches of Great Bardfield (Plate, p. 106) and Stebbing; they are designed on the same lines, but the screen at Stebbing has been much restored. Many oak rood-screens survive from pre-Reformation days, but they are not of particular merit, and in no case has the loft survived; the best are at Wimbish (Plate, p. 349), Finchingfield (Plate, p. 87) and Rickling (Plate, p. 222), of the 14th century, and at Manuden (Plate, p. 195), Finchingfield (Plate, p. 87) and Henham, of the 15th century. The screens at Foxearth, Clavering, Great Yeldham and Stambourne have painted figures of saints on the lower panels—restored at Foxearth and much defaced in two of the other examples. The rich fragment at Ridgewell (Plate, p. xxxiii) is also decorated with colour. At Bardfield Saling a good 14th-century screen is now used as a reredos.

Sedilia:—In many churches the sedilia have been obtained by cutting down the recess of a window to form a seat. Bulmer, Great Dunmow, Great Sampford (Plate, p. 136), Shalford and Tilty have arcaded sedilia of the 14th century, which in most cases range with the piscina.

Staircases:—Good late 16th or early 17th-century wooden staircases survive at Berden Hall, Little Sampford Hall (Plate, p. 188), Audley End, Saffron Walden (Plates, pp. xxxiv, 236), Warren's Farm, Great Easton, and Little Bardfield Hall. The late 16th-century staircase-tower at Horham Hall, Thaxted, is unusual. A house (10) at Clavering has a complete late 17th-century staircase, with painted walls and ceiling.

Stalls and Seating:—The finest stalls are the range of five at Castle Hedingham, with their carved baberies (Plate, p. xxxiii); good standards with carved popeys occur at Shalford, Gosfield and Belchamp St. Pauls (Plate, p. xxxiii). At Wendens Ambo is a pew-front with a carved 'tiger and mirror' (fig., p. 357). The set of 17th-century panelled and carved bench-ends at Thaxted are probably of foreign workmanship.

Stoups:—Such stoups as survive are mostly plain recesses. At Castle Hedingham there is a sculptured bowl of the 12th century (Plate, p. xxxii), and at Wendens Ambo and Great Dunmow are enriched stoups, of the 14th and 15th century respectively.

Miscellanea:—At Ridgwell (Plate, p. xxxiii) and Great Sampford are wooden Biers of the 15th and 17th century respectively. The 'Ringers' Jug,' dated 1658, at Halstead, an early 18th-century Organ with a carved case, attributed to Renatus Harris, at Little Bardfield, and a small fragment of an alabaster 'Table,' preserved at Saffron Walden, may also be noted. At Halstead is a late 13th or early 14th-century wooden Shield carved with the Bourchier arms (Plate, p. xxxiii); it probably formed part of a funeral monument.

Condition.

1. Prehistoric and Roman:—The only prehistoric camp in the district—that at Littlebury—retains the whole outline of its defences, though much denuded. Of the Bartlow Hills, the most important tumuli in the county, the four largest are well preserved, and excellent care is now taken of them.

2. Mediæval Churches, etc.:—Of the eighty-two churches described in the Inventory, two have been entirely rebuilt, while two others have been rebuilt except the tower; of those remaining, seventy-eight are old, more than half have been much restored, and in some cases partly rebuilt. Nineteen are in fairly good condition. It is noted that Manuden has a much decayed N. transept, Wimbish suffers from damp, and some of the arches at Debden are distorted by unequal settlement. Six other churches are in poor condition or have cracks in the walls, notably Borley, Bulmer, and Wethersfield. The growth of ivy on the walls is only serious in about five instances. At Hempstead and Wimbish the towers have fallen, and have not been rebuilt, and at Bardfield Saling part of the chancel has been pulled down.

Two desecrated chapels are included in the Inventory; that near Codham Hall, Wethersfield, now forms two cottages, and that at Bonhunt Farm, Wicken Bonhunt, is used for farm purposes; the structural condition of both chapels is now fairly good.

About eight per cent. of the secular buildings are in a poor or bad condition; most of them, however, are small cottages. Little Sampford Hall is in a much neglected state, and one wall at Broadoaks, Wimbish, is cracked. The more important houses are in good condition generally, but many have suffered from over restoration; this is particularly the case with Audley End House, Saffron Walden. Decayed plaster work is commonly the only defect in timber-framed houses, but many thatched roofs need renewal. The stone keep at Castle Hedingham is in a splendid state of preservation, and is well cared for. The mount and bailey there are complete, except the outer bailey on the E. side. There appears to be little advance in the decay of the rubble ruins of Saffron Walden and Stansted Mountfitchet Castles and Tilty Abbey. At Clavering and Stansted Mountfitchet the earthworks of the castles survive in a fairly complete condition.