Pages 89-121

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

BRIGHTWELL BALDWIN

Located on a spring-line at the foot of the Chiltern hills, the small rural parish of Brightwell Baldwin contains Brightwell Baldwin village and the outlying hamlet of Upperton. (fn. 1) A medieval settlement at Cadwell shrank to a single farm during the later Middle Ages. For much of its history the parish had resident lords who, with the rector, dominated its social and religious life, and it remains predominantly agricultural, with little modern development. Brightwell Park, immediately north of Brightwell village, was the site of a medieval manor house remodelled in the late 16th or early 17th century, and set amidst formal gardens. Its Georgian successor was mostly demolished c.1947–9, leaving a converted stable block and the early 19th-century landscaped parkland.

PARISH BOUNDARIES

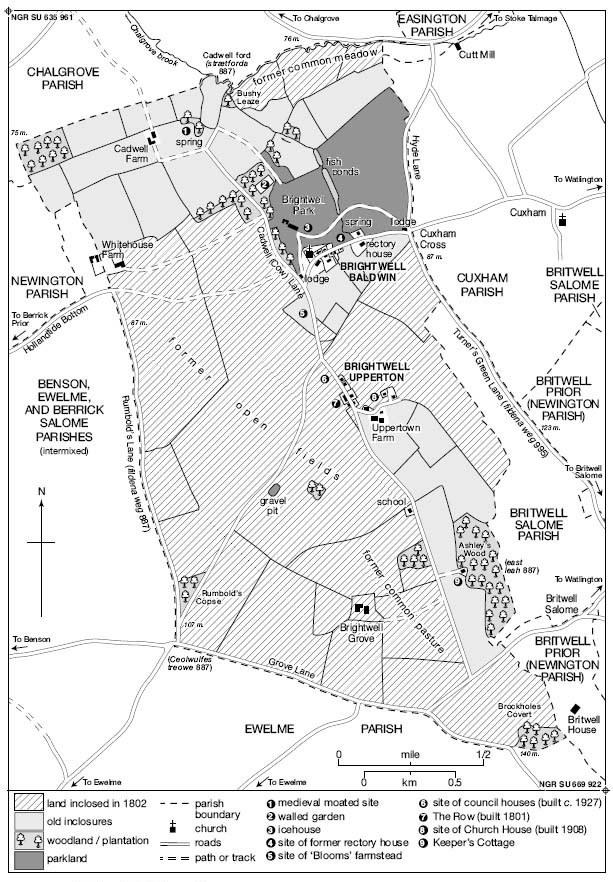

The present-day parish covers 1,612 a. (652 ha.), the same as in 1881. (fn. 2) Its boundaries derive in part from those of an estate described in 887; (fn. 3) that appears, however, to have excluded both Cadwell and an Anglo-Saxon 'hide' farm bordering Cuxham, (fn. 4) and the modern parish may not have finally emerged until after the Norman Conquest. Roads form significant stretches of its eastern, southern, and western boundaries, (fn. 5) whilst the northern boundary follows Chalgrove brook and (from Cadwell ford) an ancient hedgerow north of Cadwell Farm. The outlines of former arable furlongs, visible in the eastern boundary with Cuxham and Britwell Salome, suggest that those stretches post-date the creation of the open fields, and a boundary stone beside the Brightwell-Cuxham road was mentioned in 1797, perhaps replacing a medieval cross. (fn. 6) The 9th-century boundary-markers east leah ('east wood-pasture') and strœtforda ('street ford') referred probably to present-day Ashley's wood (fn. 7) and Cadwell ford, (fn. 8) while detached meadow belonging to the 9th-century estate lay near the strœtforda. Detached woodland at scylfhrycg ('shelf ridge') may have been in Nettlebed, where some woods were said in 1565 to have belonged to Brightwell Baldwin 'time out of mind'. (fn. 9)

LANDSCAPE

The parish is characterized by gently undulating countryside with no dramatic contrasts. Land rises from 75 m. in the north to 140 m. in the south-east corner, with much of the parish lying between 80 and 110 metres. (fn. 10) A hillock west of Brightwell Baldwin village is probably that called cadandune ('Cada's hill') in 887, when the adjacent dry valley called Hollandtide Bottom was known as holandene ('hollow valley'). (fn. 11)

Two of the parish's medieval settlements developed close to springs, recalled in the Anglo-Saxon placenames Brightwell ('bright or clear spring') and Cadwell ('Cada's spring'). (fn. 12) The Brightwell spring feeds a stream flowing northwards to Chalgrove brook through two fishponds, which are perhaps of 13th-century origin and served later as ornamental features in the manorhouse parkland. (fn. 13) Cadwell's spring fed a medieval moat, (fn. 14) and empties directly into Chalgrove brook. Surface water is absent on the higher ground south and west of Upperton.

The parish's varied soils include poorly-drained alluvium and Gault Clay along the streams in the north (traditionally supporting meadow and pasture), and Upper Greensand around Cadwell and Brightwell Park (providing a fertile loam used for arable and pasture). Elsewhere, Lower Chalk with superficial deposits of sand and gravel provided well-drained soils chiefly used for arable. Gravels west of Upperton were being quarried by 1802 if not earlier, and before inclosure the sandy soils around Brightwell Grove in the south-east were covered with scrubby heathland and woods, of which Ashley's wood is probably a remnant. (fn. 15) Stands of trees are also found near Brightwell Park, where some form of parkland may have existed in the medieval period. Formal gardens laid out there in the 17th century were swept away in the early 19th, when the park was redesigned in the English Landscape style. (fn. 16)

Brightwell Baldwin parish c.1880.

COMMUNICATIONS

The main road through Brightwell Baldwin village may have formed part of the Lower Icknield Way, a Romanized prehistoric trackway which probably entered the parish at Hollandtide Bottom in the west and exited at Cuxham Cross in the east, continuing through Cuxham. (fn. 17) Cadwell (or Cow) Lane, branching off it close to Brightwell Park, formerly connected Brightwell Baldwin with Cadwell and Chalgrove to the north, (fn. 18) and may have also been in use in the Roman period, since the point where it crossed Chalgrove brook (known by 1588 as Cadwell Ford) (fn. 19) was in 887 called strœtforda or 'street ford'. (fn. 20) Rumbold's Lane along the western parish boundary (named probably from a 17th-century parishioner) (fn. 21) was called a fildena weg or 'fielden way' in 887, while Turners Green Lane in the east (heading south to Britwell Prior) was similarly named in 995, both routes probably linking the clay vale with the Chiltern uplands. (fn. 22) Grove Lane, on the southern border with Ewelme, forms part of a road from Benson to Watlington. Lanes leading north, south-west, and south-east from Upperton are presumably of medieval or earlier origin, and formed part of a dense network of paths rationalized at inclosure in 1802. (fn. 23)

Brightwell Baldwin lacked its own carrier, and had no public transport until the late 20th century when a weekly Wallingford bus service was established. (fn. 24) Post was delivered through Tetsworth by 1854, (fn. 25) and c.1899 the estate foreman Joseph Selwood and his wife opened a village post office. By 1911 it was a telegraph office, and from the 1920s it included a grocers shop, (fn. 26) but after changing location several times it closed in 1985. (fn. 27)

POPULATION

The recorded population in 1086 (none of it in Cadwell) comprised 20 tenants and two servi, perhaps 100 people in all. (fn. 28) By 1279 Cadwell had seven tenant households besides its resident lord, while Brightwells manors and freehold estates had c.80 named tenants, of whom at least 70 were probably resident. (fn. 29) Between 1306 and 1327 the population may have declined, since the number of taxpayers fell from 29 to 23 in Brightwell and from 6 to 4 in Cadwell, (fn. 30) followed presumably by mortality during the Black Death. Even so the poll tax of 1377 was paid by 104 people in Brightwell, and by 13 in Cadwell. (fn. 31)

Sixteenth-century tax records give little indication of the parish's population, (fn. 32) but 37 households were assessed for a parish rate in 1587, (fn. 33) and 32 for hearth tax in 1662. (fn. 34) In 1676 the adult population was estimated at 207, (fn. 35) and in 1738 there were said to be around 25 families, (fn. 36) although 51 households were reported in 1768. (fn. 37) Numbers rose from 237 in 52 households in 1801 to 332 in 1831, falling gradually to 220 (in 58 households) over the next fifty years. A brief recovery before 1891 was followed by further decline, the population fluctuating in the 100s until a rise to 199 (in 80 households) in 2001, and to 208 in 2011. (fn. 38)

SETTLEMENT

Little evidence of prehistoric occupation is known, save for a Palaeolithic flint hand-axe found at Upperton. (fn. 39) Roman activity is suggested by antiquarian finds of a glass cremation jar and pottery urn at Bushy Leaze east of Cadwell, tiles between Berrick Salome and Brightwell, and a pot containing c.1,500 coins in an open field in Brightwell. (fn. 40) No structural evidence has been found, however, and it is unclear whether 11 coins of late 2nd- to late 4th-century date recovered at Cadwell Farm are casual losses or indicate Roman settlement. (fn. 41)

Early (5th- to 6th-century) Anglo-Saxon burials have been found just beyond the parish's south-west corner, close to the 9th-century boundary marker 'Ceolwulf 's tree', (fn. 42) and it seems likely that in the early or middle Anglo-Saxon period small communities were established near the springs from which Brightwell and Cadwell are named. (fn. 43) 'Hyde' place-names east of Brightwell Park may indicate a lost pre-Conquest farmstead, (fn. 44) and by 1086 Brightwell contained two separate estates, a division perhaps perpetuated in the later settlements of Brightwell Baldwin and Upperton. (fn. 45) The latter was apparently called Upper Brightwell (Brihtewella superior) c.1150, (fn. 46) and the alternative name of Overton is recorded from 1232. (fn. 47) Brightwell Baldwin itself was sometimes known as 'East Brightwell', distinguishing it from Brightwell near Wallingford, (fn. 48) while the affix 'Baldwin recalls its ownership by Sir Baldwin Bereford (c.1356–1405). (fn. 49)

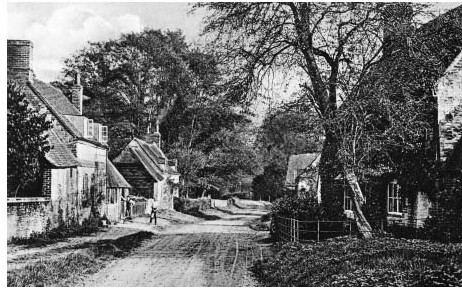

Brightwell Baldwin from the south-west in 1949, showing Brightwell Park (top left), the church, and the main village street.

Settlement remains concentrated on the three medieval sites of Brightwell Baldwin, Upperton, and Cadwell, save for establishment of an outlying house and farm at Brightwell Grove following inclosure in the early 19th century (fn. 50) Brightwell Baldwin is now a linear village on the southern edge of Brightwell Park, its houses arranged in two semi-regular rows north and south of the village street. The north row contains the medieval church and the site of the rectory house, relocated to the streets south side in 1804. (fn. 51) Brightwell Baldwin manor house (established by 1300) stood within the modern parkland, which may be of medieval origin, and a manor house for the separate Parks manor was probably also in the village. (fn. 52) Two lodges serving Brightwell Park were built after 1802, and some buildings were demolished in the following decades, including houses immediately east and west of the church. (fn. 53) In 1891 the estate gave materials from two old cottages to be used in building the parish room. (fn. 54) New estate cottages erected in the late 19th and 20th centuries included a brick semi-detached pair opposite the church (by 1900), and two bungalows on Cadwell Lane (by 1955). (fn. 55) A small 16th-century farmstead on the road towards Upperton may have succeeded a medieval one owned by the Blome family, but was probably removed by William Lowndes Stone c.1820. (fn. 56)

Cadwell from the air in 1943 (north to top right). Earthworks marking the medieval village and moated manor house site are visible east of Cadwell Farm.

Upperton itself, c.750 m. south of Brightwell Baldwin, developed probably as a loose cluster of houses near the junction of lanes leading south to the Grove and south-eastwards to Britwell Salome. An early focus may have been Uppertown Farm, which formerly had a large farmyard and which probably occupies a medieval site. (fn. 57) A 15th-century cottage survives to its north-east, (fn. 58) and others date from the 17th and 18th centuries. (fn. 59) In 1801 the lord William Lowndes Stone built a terrace of six brick cottages for his tenants, (fn. 60) and further expansion followed before 1900, when additional estate cottages were erected. (fn. 61) A house owned by the church was built in 1908, (fn. 62) and in the 1920s three semi-detached pairs of council houses were erected beside the road to Brightwell Baldwin. (fn. 63) In the later 20th century the number of dwellings in Upperton increased substantially, as new bungalows were built and barns belonging to Uppertown Farm were converted for habitation. (fn. 64) Electricity was brought to both places in 1947, and mains water in 1952. (fn. 65)

At Cadwell a small planned village developed probably in the 12th or 13th century, its earthworks still clearly visible east of Cadwell Farm in the 1940s, but subsequently ploughed out. Their outline suggests one or perhaps two rows of tofts and crofts, with a larger, apparently moated enclosure at the east end, almost certainly the site of the medieval Cadwell manor house. (fn. 66) Tax records show that the settlement was still occupied in the late 14th century, (fn. 67) but probably it shrank to a single farmstead by the 16th, when property there was subject to a series of leases. (fn. 68) The surviving Cadwell farmhouse dates mainly from the first half of the 18th century, with barns added over the following decades. (fn. 69)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

For a parish with only 86 dwellings in 2011, (fn. 70) Brightwell Baldwins older buildings display a surprisingly varied range of materials. Limestone ashlar features in the medieval church, and at Brightwell Park and its associated Cedar Lodge. Several red-brick cottages survive from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whilst most older farmhouses and cottages employ a mixture of brick and locally-sourced flint, chalk (Totternhoe Stone), and limestone rubble (coral rag). The oldest vernacular buildings are timber-framed, and several were originally thatched, before roofs of locally-made clay peg-tiles became popular in the 18th and 19th centuries. Welsh-slate roofs survive on the 'polite' classical buildings of Brightwell Park, its two lodges, the Old Rectory, and Brightwell Grove, of which the last two have symmetrical stuccoed façades. (fn. 71)

The only known medieval domestic building is Ivy Cottage in Upperton, a cruck-framed and originally four-bay open-hall house of the 15th century (fn. 72) Timber-framing may have been employed in the medieval Brightwell Baldwin manor house, which, on the basis of excavated evidence, had a tiled roof and chalk rubble walls or dwarf walls. In the 16th or 17th century the remodelled manor house may have had a brick and stone façade, perhaps not dissimilar to the surviving dovecot, which has mullioned windows and a round-arched doorway, both with decorative hoodmoulds. (fn. 73) A building of similar date is Glebe Farm, a square-framed house of three bays with a thatched roof and herringbone brick infill. (fn. 74)

Buildings with 17th-century phases include Rectory Cottages (a former farmhouse with a beam dated 1652), Uppertown Farm, the Tord Nelson pub (Fig. 28), and Shepherds Cottage, a three-bay house which (with Glebe Farm) is one of only two remaining thatched dwellings. All are timber-framed, with the possible exception of the Tord Nelson, which was remodelled in the early 18th century to form a U plan. (fn. 75) Its decorative wooden arcade reputedly re-uses timbers from the manor house burnt down in 1788. (fn. 76) Cadwell farmhouse may have been of similar size and plan to Shepherds Cottage in 1669, when it included a hall, kitchen, and milk house, each with chambers above. (fn. 77) The present farmhouse, of three bays with walls of limestone and brick, dates primarily from the early 18th century, although it may have been rebuilt around an earlier core, perhaps including the central chimneystack. Its range of three barns (which employ cranked inner principals) was probably added towards 1800. (fn. 78) Uppertown and Brightwell Farms were also rebuilt in the 18th century, each being provided with new barns and other outbuildings, (fn. 79) and some cottages were renovated or constructed anew, including the Old Forge. (fn. 80) The major building project of the late 18th century was Brightwell Park, where the new house was completed c.1790. (fn. 81)

The first decade of the 19th century saw the erection of 'polite' houses at the Old Rectory (fn. 82) and Brightwell Grove. (fn. 83) A rear wing of chequered brick was added to Brightwell Farm in 1824, (fn. 84) and the castellated and 'Gothick' Keeper's Cottage near Ashley's wood may be of similar date: clearly it was designed as an eye-catcher to be viewed from Brightwell Grove. (fn. 85) Another 'Gothick' building is the stable and coach house added to the rear of Glebe Farm, probably by the rector Samuel White (1801–41). (fn. 86) Most late 19th-century buildings (including the former school and various estate cottages) are entirely brick-built, and several display decorative diaper work, perhaps suggesting a single architect or builder. The 20th-century council houses and bungalows are unremarkable.

MANORS AND ESTATES

By the late 9th century Brightwell Baldwin belonged to the bishop of Worcester's large Readanora estate (centred on Pyrton), which may have once formed part of Benson's early royal territory (fn. 87) Six hides, representing the greater part of the later parish, were confirmed to the bishop in 887, and in 973 he leased a five-hide estate at Brightwell to a man named Byrhtric for two lives. (fn. 88) The church of Worcester had lost its interest in Brightwell by 1086, however, when the future parish comprised two separate estates at Brightwell and another at Cadwell.

The two Brightwell manors (known later as Parks and Huscarls) were joined in the 13th century by a sub-holding of Parks, which became known as Brightwell Baldwin manor. Huscarls was absorbed into it probably by the resident Cottesmore family during the 15 th century, followed by Parks manor in 1544 and Cadwell from 1627. The resulting 'Brightwell estate' covered virtually the entire parish except for the glebe in the late 18th century, and remained largely intact until 1942. Its chief house was that originally associated with Brightwell Baldwin manor, which was established by 1300 and became the parish's principal residence until its destruction by fire in 1788. Brightwell Park, the Georgian manor house which replaced it, was mostly demolished c. 1947–9, leaving a stable block which was converted into the existing house. (fn. 89)

MANORS TO 1630

Brightwell Parks Manor

In 1086 two hides in Brightwell were held by Hervey (probably Hervey de Campeaux) from Odo, bishop of Bayeux. (fn. 90) Almost certainly this was the later Brightwell Parks manor, (fn. 91) to which the advowson also belonged. (fn. 92) All four of Hervey's Oxfordshire estates (Brightwell, Little Haseley, Warpsgrove, and Thomley) belonged by the early 13th century to the Lacy family's honor of Pontefract, (fn. 93) which in 1311 became merged in the earldom (and later the duchy) of Lancaster. (fn. 94) The duchy's overlordship was still recorded in 1361 and 1401, (fn. 95) but in 1398 and 1425 the earls of March were overlords, holding of Clifford's Castle (Herefs.). (fn. 96) The link presumably arose in 1331, when Henry de Lacy's daughter Alice inherited the barony of Clifford from her mother. (fn. 97) An intermediary lordship belonged in 1206 to William de Bruges in the right of his wife Olive, daughter of Oliver of Skelbrooke, the Skelbrookes being Hervey's successors as lords of Skelbrooke near Pontefract (Yorks. W.R.). (fn. 98) Their right descended thereafter with their manor of Little Haseley, and was still recorded in 1401. (fn. 99)

Tenancy of the manor belonged by 1206 to Richard Park (de Parco), who held ⅓ knight's fee in Brightwell under William de Bruges. (fn. 100) Before 1230 Richard was succeeded by his son Walter, (fn. 101) who was dead by 1244 when his son and heir Richard was a minor in the guardianship of Simon of St Liz, (fn. 102) steward of the bishop of Chichester. (fn. 103) The bishop presented to the rectory the same year. (fn. 104) Richard died before 1264 when Oliver of Skelbrooke presented to the church as guardian of Richard's son Thomas, (fn. 105) who reached his majority by 1274 and was lord in 1279. (fn. 106) He or a namesake was living in 1304 (fn. 107) but was probably dead by 1306, when Richard Park was taxed in Brightwell; (fn. 108) Richard was succeeded between 1347 and 1364 by John Park, (fn. 109) who was resident in 1394. (fn. 110) The manor subsequently passed to Thomas Park and (before 1428) to Thomas Cowley, holding in the right of his wife Joan (formerly Park). (fn. 111)

Joan died before 1456, by which time the manor and advowson had been divided among her daughters Joan (wife of John Soulby), Elizabeth (wife of John Blackhall), and Amice (wife of Robert Barwell). (fn. 112) In 1459 (when Joans husband was Thomas Nowers) she and Elizabeth surrendered their two thirds to Thomas Stonor (d. 1474) of Stonor Park in Pyrton, (fn. 113) whose share passed to his son Sir William (d. 1494) and grandson John, a minor. Following John Stonors death in 1498 the Stonor possessions passed to his sister Anne, wife of Sir Adrian Fortescue, although their right was disputed for more than thirty years. (fn. 114) In 1509 the Fortescues reunited Brightwell Parks manor by purchasing the remaining third from Richard Barwell: (fn. 115) that third had been falsely claimed in 1504 by the lord of Brightwell Baldwin John Cottesmore, (fn. 116) who had earlier tried to present to the rectory (fn. 117) In 1522 Johns grandson John Cottesmore was lessee of all three parts of the manor, known as Uphams, Blackballs, and Barwells. (fn. 118)

Following Anne Fortescues death in 1518 Sir Adrian Fortescue married Anne, daughter of Sir William Rede of Boarstall (Bucks.). (fn. 119) He retained Brightwell Parks under a settlement of 1536, which ended the long-running disputes over the Stonor succession; (fn. 120) following his execution in 1539, however, it passed to his daughter Margaret and her husband Sir Thomas Wentworth, Lord Wentworth. (fn. 121) All or part was subsequently leased to Fortescues widow and her second husband Sir Thomas Parry, who jointly presented to the rectory in 1541. (fn. 122) In 1554 Wentworth sold the advowson and Brightwell Parks (comprising six houses and 250 a.) to the owner of Brightwell Baldwin manor, Anthony Carleton, (fn. 123) and thereafter the two manors descended together. (fn. 124)

Brightwell Huscarls Manor

A separate two-hide estate in Brightwell was held from the king in 1086 by Roger, (fn. 125) almost certainly the Roger FitzSeifrid who held a burgage in Wallingford, where he was probably a royal housecarl. With his brother Ralph, Roger also held lands in Berkshire, which by the mid 12th century (together with the Brightwell estate and holdings in Surrey) formed three knights fees within the honor of Wallingford, all of them held by the Huscarl family (fn. 126)

In 1166 the three fees were held by Gilbert Huscarl, and in 1196 by Roland, the heir of Richard Huscarl, perhaps Gilberts grandson. Roland was succeeded in 1211 or 1212 by his son Thomas, (fn. 127) whose Brightwell estate was granted by the king to Richard Park in 1216; (fn. 128) it was evidently restored to the Huscarls soon afterwards, however, as Agnes the widow of Roger Huscarl of Brightwell surrendered property in Cuxham c.1230. (fn. 129) Rogers son William Huscarl held ¼ knights fee of the honor in 1235, (fn. 130) and in 1279 Thomas Huscarl held the Brightwell manor as ½ knights fee, in which William Huscarls widow Joan retained dower. By then the manor included a ploughland in demesne and a share in a mill, together with numerous villein tenancies. (fn. 131) By 1300 the combined Huscarl fees belonged to Roland Huscarl, (fn. 132) who with his wife Margaret retained Brightwell in 1307. (fn. 133)

Roland's son Thomas came of age in 1313 and was taxed in Brightwell in 1327. Possibly he was the father of Sir Thomas Huscarl, who c.1343 married (as his second wife) Lucy, daughter and heir of Sir Richard Willoughby. (fn. 134) The Brightwell manor was settled on them in 1349 with remainder to their son Thomas, (fn. 135) and Lucy retained it following Sir Thomas's death by 1352. In 1357 she married Nicholas Carew of Beddington (Surrey), twice MP for Surrey and keeper of the privy seal, (fn. 136) to whom the trustees of Sir Thomas and Lucy's son and heir Thomas Huscarl granted the estate in 1369. (fn. 137) Nicholas sold the manor in 1373 to John James of Wallingford, (fn. 138) MP for the borough, who the same year exchanged it with Sir Baldwin Bereford, lord of Brightwell Baldwin, for his manor of Rush in Clapcot (Berks.). (fn. 139)

Sir Baldwin Bereford died in 1405, (fn. 140) when the manor passed to his widow Elizabeth (d. 1423) under an earlier settlement. Thereafter it passed in halves to descendants of Sir Baldwins aunt Agnes: Maud, wife of the Dorset MP Sir Ivo FitzWaryn, and Sir Baldwin St George (d. 1425), MP for Cambridgeshire. The FitzWaryns' share passed to their daughter Eleanor (d. 1433), who settled it on her husband Ralph Bush (d. 1441), MP for Dorset, and their sons William and John. (fn. 141) Sir Baldwin St Georges share probably passed by 1423 to his grandson William. (fn. 142) Nothing further is known of either share, and probably the manor was absorbed into the Brightwell Baldwin estate by John Cottesmore (d. 1439) or one of his successors. (fn. 143)

Cadwell Manor

A small three-yardland estate at Cadwell was held from the king by Brun the priest in 1086. (fn. 144) By the late 12th century it evidently belonged to the d'Oilly family's barony of Hook Norton, (fn. 145) and was subject to complex subinfeudation. An intermediate lordship belonged to the de Whitfield family (lords of Wheatfield), who claimed descent from Peter, a sheriff of Oxfordshire in the 1090s and one of Robert d'Oilly's knights. Henry de Whitfield gained possession of his brother Roberts Cadwell lands in 1196, (fn. 146) and by the 13th century the manor was held under the Whitfelds by the Salveyn family, who in 1279 held it in socage for 405. rent. (fn. 147)

Rival claims by the Foliots led to protracted disputes during the early 13th century, when Richard Foliot alleged that Henry d'Oilly (d. 1196) had granted a hide of land to his father Ralph Foliot, who in turn had leased it to Gilbert Salveyn for life only. Following Gilbert's death Ralph had allegedly been deprived in favour of Salveyn's son William. Foliot won his case in 1205 (fn. 148) and received possession in 1216, (fn. 149) until further challenged by William Salveyn's son William in 1224. (fn. 150) The Salveyns evidently prevailed, (fn. 151) and in 1279 John Salveyn was lord there with ½ hide of demesne and seven tenants. (fn. 152) He or a namesake retained the manor in 1326–27, (fn. 153) later lords including Richard Salveyn (fl. 1357 and 1373), (fn. 154) and probably John Salveyn (fl. 1387). (fn. 155)

Nothing further is known until 1475 when Alice de la Pole, lady of Ewelme and dowager duchess of Suffolk, owned property in Cadwell and Brightwell. (fn. 156) The estate remained attached to Ewelme manor until the latter's sale by the Crown in 1627, (fn. 157) and in the 16th and early 17th centuries it was leased in two portions. One, comprising 130 a. in Cadwell and Brightwell, (fn. 158) was held from 1576 by Joyce Carleton, lady of Brightwell Baldwin manor, (fn. 159) who in 1588 assigned her lease to her son George. (fn. 160) In 1595 he secured the reversion from John Dixon, a London scrivener to whom the Crown had granted it for 31 years beginning in 1619. A separate 21-year lease covering the period 1598–1619 was granted to John Walker in 1583, but was evidently assigned to John Simeon (d. 1618) of Pyrton. (fn. 161) He subsequently acquired all of the Carletons' Brightwell property, including Joyce's Cadwell lease in 1595 and Dixon's in 1596, both from George Carleton. (fn. 162)

The second portion, described as the site of Cadwell manor, was let to Thomas Muskett in 1534 for 41 years. (fn. 163) Thomas sublet it to Thomas Carter of Swyncombe, succeeded in 1551 by his son Brian. (fn. 164) In 1565 the queen granted reversion of Muskett's lease to John Fortescue, master of the wardrobe, for 21 years from 1575, renewing the grant in 1582 for a further 60 years. (fn. 165) In 1583, however, Fortescue assigned his lease to Sir Francis Knollys, treasurer of the royal household, on whose death in 1596 it passed to his son William, a courtier created earl of Banbury in 1626. (fn. 166) William assigned the lease to Thomas Wotton of Warpsgrove in 1627, (fn. 167) when the reversion was granted to John Simeon's son Sir George. (fn. 168)

The reunited Cadwell estate (264 a. in 1638) (fn. 169) descended thereafter with the combined Brightwell manors, (fn. 170) although like the rest of the former Ewelme manor it owed fixed fee farm rents to the Crown. Cadwell's share of £13 a year was paid by successive lords of Brightwell Baldwin throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. (fn. 171)

Brightwell Baldwin Manor

The sub-manor known later as Brightwell Baldwin (fn. 172) existed by 1231, when Robert of Brightwell held half a hide from Walter Park as 1/10 knights fee. (fn. 173) The manor was still reckoned at 1/10 fee in 1326 but at a ½ fee in 1355, when it was still held of the Parks. (fn. 174) By the early 15th century it belonged to the honor of Wallingford, superseded from 1540 by the honor of Ewelme. (fn. 175)

Around 1236 Robert of Brightwell's daughter Maud married Geoffrey Langley, (fn. 176) on whom Robert settled ½ yardlands, 13 a. of meadow, and 9 houses in Brightwell which he had previously given to Maud. (fn. 177) Geoffrey, who held separate land in Brightwell from Dorchester abbey, (fn. 178) was later knighted and held various royal offices. At his death in 1274 his Brightwell lands passed presumably to his son Robert, (fn. 179) whose half-brother Sir Geoffrey Langley, a leading diplomat, (fn. 180) inherited before 1279. (fn. 181) In 1286 he mortgaged the estate (henceforth called a manor) to Sir William Bereford, (fn. 182) chief justice of common pleas, who by 1300 was lord in his own right and maintained a manor house. (fn. 183) William (d. 1326) was succeeded by his widow Margaret and son Edmund, (fn. 184) who in 1335 was granted free warren in Brightwell. (fn. 185) Following Edmunds death in 1354 the manor passed successively to his illegitimate sons Sir John (d. c.1356) and Sir Baldwin, (fn. 186) who added Brightwell Huscarls in 1373. (fn. 187) After his death in 1405 (fn. 188) the manor probably passed with Huscarls to his widow Elizabeth (d. 1423), (fn. 189) and like Huscarls was apparently held in halves by Ralph Bush (in the right of his wife Eleanor) and William St George in 1423, when John Langley lodged a claim. (fn. 190)

The subsequent descent is unclear, but in 1432 Robert FitzRalph and his wife Margaret, a descendant of Edmund Bereford's sister Agnes, surrendered the manor to Sir John (I) Cottesmore and his wife Amice. (fn. 191) Cottesmore, who held land in Brightwell by 1429, (fn. 192) was chief justice of common pleas and lord of neighbouring Britwell Salome, with which Brightwell Baldwin probably passed on his death in 1439 to his widow Amice. She married Matthew Hay, on whose death after 1453 the manor probably descended to John (II) or John (III) Cottesmore, son and grandson of John (I). (fn. 193) John (III), who held it in 1494, (fn. 194) was subsequently knighted and died c.1510, to be succeeded by his son William (d. 1519). (fn. 195) Williams second wife Alice married Thomas Doyley of Hambleden (Bucks.) (fn. 196) and retained a life interest, (fn. 197) leasing the manor to Williams son John (IV) Cottesmore for 70 years in 1520. (fn. 198) In 1539 he conveyed it (apparently illegally) to Sir Michael Dormer, (fn. 199) citizen and alderman of London, who sold it after 1542 to John Carleton of Walton-on-Thames (Surrey). Alice Doyley's life interest was upheld in 1550 when Carleton was forced to become her tenant, (fn. 200) but the following year he died apparently possessed of the freehold. (fn. 201)

Carleton's son Anthony added Brightwell Parks manor in 1554, becoming MP for Westbury (Wilts.) in 1559. (fn. 202) He died in 1576 leaving his Brightwell estates to his widow Joyce for life, with remainder to their son George, a minor. (fn. 203) George was dealing with both manors by 1589, (fn. 204) and c.1596 sold them to John Simeon of Pyrton (d. 1618), (fn. 205) succeeded by his son Sir George, MP for Wallingford. (fn. 206) Sir Georges acquisition of Cadwell in 1627 created a unified Brightwell estate which included most of the parish. (fn. 207)

THE BRIGHTWELL ESTATE FROM 1630

The combined estate was returned to the Carleton family in 1630, when Sir George Simeon sold it to George Carleton's younger brother Sir Dudley Carleton (d. 1632), Viscount Dorchester, who served as principal secretary of state 1628–32. (fn. 208) Dudleys second wife Anne, dowager Viscountess Bayning of Sudbury (Suffolk), retained a life interest and died in 1639; she was succeeded by Sir George Carleton (d. 1650), son of Sir Dudleys nephew and heir Sir John Carleton, Bt, of Cheveley (Cambs.), who had died in 1637. (fn. 209) Sir Georges coheirs were his sisters Anne, wife of George Garth of Morden (Surrey), and Catherine, (fn. 210) who c.1653 married John Stone of Great Stukeley (Hunts.), and with her husband purchased the Garths' share. (fn. 211) Stone later served as MP for Wallingford, (fn. 212) and remained lord following Catherines death in 1668. (fn. 213)

Under a settlement by Act of Parliament in 1702 Stones Brightwell estate passed on his death in 1704 to his son Carleton Stone (d. 1708), and then to Carleton's brother John (d. 1732), (fn. 214) whose widow Mary retained a life interest. The younger John Stones heir was his cousin Francis Lowe of Ridgmont (Beds.), (fn. 215) who inherited on Mary's death in 1739. (fn. 216) On Francis's death in 1754 it passed to his daughter Catherine and her husband William Lowndes, originally of Astwood (Bucks.), who in 1755 both took the additional surname Stone by Act of Parliament as a condition of inheriting the estate. (fn. 217) William (d. 1772) and Catherine (d. 1789) were succeeded by their son William (d. 1830) (fn. 218) and by William's son William Francis Lowndes Stone, (fn. 219) who owned 1,585 a. in the parish c.1850 (fn. 220) and was succeeded by his granddaughter Catherine Charlotte Lowndes Stone, then a minor. Her guardian and uncle by marriage was the rector of Brightwell, George Day, who administered the estate for four years until her majority (fn. 221) In 1862 Catherine married the soldier Robert Thomas Lowndes Norton of Anningsley Park in Chertsey (Surrey), their marriage settlement requiring every family member succeeding to the Brightwell estate to bear the names and arms of Lowndes, Stone, and Norton. The arrangement received royal licence in 1868. On Catherine's death in 1882 the estate passed to her son Roger Fletcher Earle Lowndes-Stone-Norton (d. 1934), (fn. 222) followed by his son Fletcher William Lowndes-Stone-Norton. (fn. 223)

In 1942 the 1,672-a. estate was broken up in a series of sales. (fn. 224) The manor house and 458 a. (including Brightwell farm) was sold to George Coldham Knight, who the same year conveyed the property to Dorothy Anne Mackle. (fn. 225) Around 1946 she sold the greater part to Richard Noel Richmond-Watson, who in 1955 owned 438 a. in the parish. In that year Brightwell farm (260 a.) was purchased by its tenant and the remaining estate was sold to Frank Dudley Wright. On Wright's death in 1994 it passed to his daughters Tessa Mogg and Angela Riley, who in 2011 sold Brightwell Park with 135 a. to the sculptor Anish Kapoor. (fn. 226)

MANOR HOUSES

Brightwell Parks, Brightwell Huscarls, and Cadwell

Brightwell Parks manor presumably had a manor house in 1325, when Richard Park lived in Brightwell. (fn. 227) Its location is unknown, though as the advowson belonged to the manor it may have stood near the church in Brightwell Baldwin village. From the early 15th century the Parks' successors lived elsewhere, and the house was presumably abandoned.

The 'site' of Cadwell manor leased in the 16th century was presumably that marked by remains of a moat c.200 m. east of Cadwell Farm, a view supported by recent archaeology. The Salveyns probably lived there as resident lords, but by the late 15th century it had most likely been abandoned, and in the post-medieval period the principal dwelling at Cadwell was Cadwell Farm. (fn. 228) No record of a house for Brightwell Huscarls manor has been found, the Huscarls themselves being based at Purley (Berks.), and Nicholas Carew at Beddington (Surrey). (fn. 229) Sir Baldwin Bereford probably occupied the Brightwell Baldwin manor house. (fn. 230)

Brightwell Baldwin Manor House (Brightwell Park)

The House to 1788 The Berefords' and Cottesmores' medieval house almost certainly lay in modern parkland c.300 m. north of the parish church, at a site identified by recent archaeology (fn. 231) Its origins may lie in a free tenement and 'new garden held by Geoffrey Langley in 1248, (fn. 232) and a manor house existed by 1300 when a robbery occurred there. (fn. 233) In 1326 the demesne included two gardens and two dovecots. (fn. 234) The lords' status suggests a well-appointed residence which presumably incorporated a great hall, and may have been arranged around a courtyard with a gatehouse. An excavated building with chalkstone walls, detached from the main complex, may be the chapel for which Sir Baldwin Bereford obtained a papal licence in 1397. (fn. 235) The chapels east end was mentioned in 1520, when the house had 'over' and 'nether' chambers suggesting a two-storeyed solar block, while appurtenances included a 'water gate', barns, granary, and guest stable'. (fn. 236)

Brightwell Park: the main south-west front in the 1930S–40S, with the service wing (heightened in 1874) on the left. The main house was mostly demolished c. 1947–9.

Most post-medieval owners continued to live at Brightwell, (fn. 237) and archaeology indicates extensive remodelling for the Carletons or Simeons in the late 16th and early 17th century, creating a grand residence with an ornamental terrace and formal gardens. Building work was perhaps under way in 1632, when Lady Dorchester was forced to live elsewhere. (fn. 238) The surviving two-storey dovecot, built of limestone rubble with ashlar quoins and brick dressings on an elongated Greek cross plan, dates from that period, (fn. 239) and in 1662 John Stone was taxed on 30 hearths. (fn. 240) The name Brightwell House was established by 1730, (fn. 241) and a private chapel (perhaps the medieval one) was noted in 1738. (fn. 242) Later in the 18th century the park gained a brick-built icehouse and a walled kitchen garden, and some of the straight, tree-lined carriage drives running through the park in the 1790s may have also originated in the 17th or early 18th century (fn. 243)

The House since 1788 In March 1788 the house and much of its contents were destroyed by fire, (fn. 244) but within a few years William Lowndes Stone had completed a new house on a site c.200 m. to the west. (fn. 245) Called Brightwell House or Brightwell Park, (fn. 246) it was a square, classically-designed building of three storeys and five bays, faced in limestone ashlar, and featuring a pedimented central bay on its principal façade and a semi-circular central bay to the rear. (fn. 247) Vaulted cellars lay beneath, and a single-storey adjoining service wing contained kitchens and offices. An adjacent surviving stable block is in similar style, built on a U plan. The surrounding parkland was landscaped in the naturalistic style of Humphry Repton, (fn. 248) to include an ornamental bridge known later as the Waterloo bridge, and two sinuous and tree-lined carriage drives, each leading to classical lodges and formal gates. The Cedar drive, lined with cedar trees, leads to the ashlar-faced Cedar lodge, while the Eagle drive leads to the chalk-rubble and brick Eagle lodge, where limestone eagles surmount the gate piers. (fn. 249) Repton's direct involvement remains unproven, although a watercolour by him depicting Brightwell Park was engraved and published in 1797. (fn. 250)

From the mid 19th century the lords of Brightwell Baldwin lived elsewhere, (fn. 251) and in 1862 Brightwell Park was in disrepair. (fn. 252) The house was leased, and during the Second World War accommodated two boys' preparatory schools evacuated from London and Hampshire. (fn. 253) Two storeys were added to the service wing in 1874, (fn. 254) raising it almost to the height of the main block, but the house became increasingly dilapidated and c. 1947–9 was demolished piecemeal, (fn. 255) leaving only the four ground-floor walls and the former front door. Some mahogany doors and oak flooring were reused in the stable block, which was converted into the principal residence. The top two storeys of the service wing, which was re-named Dower House, were converted into flats, but the ground floor became disused and remained so in 2011, when a few original features remained. (fn. 256)

OTHER ESTATES

In the Middle Ages several monastic institutions held small parcels in the parish. Missenden abbey (Bucks.) received a yardland from Peter Boterel (d. 1165), lord of Chalgrove, and in 1230 claimed rents from a mill. (fn. 257) The yardland was let to tenants, (fn. 258) and c.1357 (when occupied by John Bereford) the property included a dovecot. (fn. 259) Dorchester abbey acquired an estate before 1244, including ½ yardland on which Geoffrey Langley obtained permission in 1248 to build a mill and fishponds. (fn. 260) That land was held from the abbey by Langley's son in 1279, when Dorchester's Brightwell estate comprised 2½ yardlands including two held under Brightwell Parks manor. (fn. 261) In 1306 the abbey paid the highest tax in Brightwell, (fn. 262) and at the Dissolution retained 2s. annual rent there. (fn. 263)

Smaller estates included ½ yardland owned by Littlemore priory in 1279, (fn. 264) increased by the 1350s to two yardlands and a chief house leased to John Bereford for 14s.4d. annual rent. (fn. 265) Following the Dissolution, the priory's Brightwell property was sold in 1588 to Edward Wymarke of London. (fn. 266) An estate at Cadwell was owned by the hospital of St John the Baptist in Oxford in 1293, when it had two tenants, (fn. 267) and passed apparently to Magdalen College as the hospital's successor. In 1590 it comprised a parcel at Bushy Leaze in the parish's north-east corner. (fn. 268) An acre of meadow was given to Holy Trinity priory in Wallingford by John son of Aumary of 'East Brightwell' c.1260, (fn. 269) and in 1528 was apparently granted to Cardinal Wolsey in support of Cardinal College, Oxford. (fn. 270)

Other lesser estates were in lay hands. In 1279 Reginald le Bracy held 5½ yardlands from William Barentin of the honor of Wallingford, by serjeanty of providing a horse and arms for 40 days. (fn. 271) The estate is not otherwise recorded, but was probably associated with the Barentins' Chalgrove manor. John Blome of Great Kimble (Bucks.) owned land in all four manors in the parish at his death in 1357, (fn. 272) presumably including the later Blomes or Blooms close. (fn. 273) Later freeholds included three tenements attached to Marsh Baldon manor in the 16th and 17th centuries, (fn. 274) and a farm called Spyers purchased by John Stone before 1697. (fn. 275)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Brightwell Baldwin pursued the arable-based mixed farming typical of the vale. Its open fields were inclosed in 1802, and thereafter the proportion of arable increased yet further, as the former heath (used primarily for sheep grazing) was converted to tillage. Dairying was practised in the north of the parish, where streamside meadows provided hay, and watercress was grown from c.1860, in beds fed with spring water. By 1850 there were six farms, all (except the rector's Glebe farm) belonging to the Brightwell estate. The parish also supported a typical range of rural crafts and trades including a long-lived forge, while gravel was dug near Upperton.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 22)

Indentations in Brightwell's eastern boundary suggest that open fields were established early, probably before the Norman Conquest. (fn. 276) A 'middle field' was mentioned c.1290, (fn. 277) presumably accompanied by the north and Grove (or south) fields mentioned in 1421. (fn. 278) Of those, the north field may have been that occasionally called 'the hide', (fn. 279) suggesting that it began as a discrete Anglo-Saxon farm worked perhaps by a free peasant and his family (fn. 280) In 1423 it contained at least 114 a. in six furlongs. (fn. 281) Cadwell field (south-west of Cadwell Farm) was separately mentioned in 1311. (fn. 282) By 1802 the open fields as a whole covered c.1,036 a., divided amongst Cadwell, Grove, Grove Gravel, Middle, and Ham fields. (fn. 283)

Meadows were largely confined to the wetter lands bordering streams at Cadwell and north of Brightwell Baldwin village. Those mentioned in 887 and 1086 (fn. 284) almost certainly lay in the parish's north-east corner, where common meadow in 1802 comprised 40 a. in two adjacent parcels. (fn. 285) In 1623 some or all was lot meadow (fn. 286) Common grazing was available in the open fields after harvest (fn. 287) and in a 225-a. heath in the south-east, reached by a driftway from Upperton. (fn. 288) Known by the late 13th century as the Grove, (fn. 289) it was used primarily for sheep in the 18th century, when freeholders could cut fern and furze there. (fn. 290)

Some inclosed pasture near the meadows existed by 1248, when Geoffrey Langley was allowed to construct fishponds and a mill at 'Horscroft', (fn. 291) and by the late 16th century pasture closes near Cadwell Farm totalled 104 a., presumably following late medieval depopulation and inclosure. (fn. 292) Inclosed parkland around Brightwell Baldwin manor house in 1628 included c.45 a. in closes called Upper Park, Lower Park, and Ram Acre, (fn. 293) some of them possibly of medieval origin.

The 9th-century Brightwell estate may have had access to woods in the Chilterns, (fn. 294) and 40 a. of wood was recorded in 1086. (fn. 295) Woodland in the parish itself has never been extensive, however. Ashley's wood may be a remnant of the east leah ('east wood-pasture') mentioned in 887, and in the mid 19th century covered 29 acres. (fn. 296) Rumbold's copse (4 a. c.1850) existed by 1797, together with pockets of woodland in the manor-house park, (fn. 297) and in 1801 woods and plantations covered 69 a. in all. (fn. 298) The area increased slightly in the 19th century as coverts were planted for foxes and game. (fn. 299)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

In 1086 the two Brightwell estates had identical agricultural resources, comprising arable for six ploughteams, 6 a. of meadow, and 20 a. of woodland. Arable clearly predominated, although neither estate was worked to its full capacity. Hervey's estate (that later known as Parks) had two ploughteams in demesne, and two more shared by five villani and five bordars; its annual value had risen to 705. from 505. in 1066. Roger's estate (known later as Huscarls) had two ploughteams and two servi on its demesne, whilst eight villani and two bordars shared a further three ploughs. That estate had doubled in value to 1005. a year. The much smaller Cadwell estate (only three yardlands) was farmed directly with one ploughteam but no tenants, its annual value rising from 205. to 30s. (fn. 300)

By 1279 villeins on all three manors typically held a yardland or half yardland for cash rents and labour services, including ploughing, harrowing, sowing, weeding, reaping, haymaking, and carting. Similar services were owed by cottars. The lords usually provided food and drink during boon work, and some tenants received hay or sheaves. Certain villeins on Cadwell manor also had to pull the lord's flax, whilst those on Huscarls manor could pay two quarters of corn to release them from carriage service, and one Parks tenant was obliged to tend the lord's garden. Demesne farms covered a ploughland (c.120 a.) on both Parks and Huscarls manors, and half as much at Cadwell. Complex subletting and leasing of land (sometimes in very small parcels) was common, particularly amongst Brightwell's free tenants. (fn. 301)

Under the Berefords Brightwell Baldwin manor emerged as an independent economic unit, (fn. 302) and by 1326 Sir William Bereford held (amongst other assets) two dovecots worth 65. 8d. a year, 75 a. of arable worth 25s., 16 a. of mowing meadows worth 135. 4d., and £3 rents from free tenants. (fn. 303) Parks manor in 1365 included 200 a. of arable, 4 a. of meadow, 20 a. of pasture, and £2 165. rents. (fn. 304) Little evidence survives for the crops grown, although the 14th-century field names 'Ruylond' and 'Ruycroft' imply that they included rye. (fn. 305)

After the Black Death some inhabitants took on vacant tenements not only in Brightwell but in Cuxham and Chalgrove, (fn. 306) and intercommoning with Cuxham may have taken place in the 14th and 15th centuries. (fn. 307) Several Brightwell people were fined for allowing sheep, horses, and cows to trample crops there, (fn. 308) and the Cuxham bailiff's account for 1358–9 lists payments to mowers in Brightwell meadow (fn. 309) Sheep husbandry may have grown in importance in the later Middle Ages, perhaps partly in new inclosures at Cadwell. (fn. 310) The surname Shepherd appears in the parish at this time, (fn. 311) and a Brightwell man kept at least 40 sheep in 1355. (fn. 312) An Upperton resident was acquitted for theft of a sheep in 1398. (fn. 313)

FARMS AND FARMING I500–1800

Mixed farming continued in the early modern period, with cereals (principally wheat, barley, oats, and rye) featuring prominently in parishioners' wills and inventories alongside legumes such as peas, beans, and vetches. (fn. 314) A husbandman in 1557 left a plough to his son, and 4d. to every Brightwell man without one. (fn. 315) References to the 'wheat field' and 'barley field' suggest a three-course rotation, and by 1647 (and probably long before) the open fields were managed by a homage which met each February, inspecting the boundary marks of every furlong and acre. (fn. 316) Some grain was evidently used for brewing, with several inhabitants owning malt mills, (fn. 317) and at least one maintaining a hop garden. (fn. 318)

Several farmers kept flocks, (fn. 319) and some employed shepherds. (fn. 320) Sheep (stinted at 50 per yardland) were traditionally folded in the open fields after harvest, (fn. 321) and also in the Grove, which by the 18th century contained six allotments or 'slays' each held by a principal tenant for his own flock. (fn. 322) One tenant in 1731 had pasture for 125 sheep. (fn. 323) Cattle were also prominent, and several farms possessed dairies and cheese presses: (fn. 324) John Pamplin (d. 1669) of Cadwell left 200 cheeses worth £2 2s. 6d., and in 1733 the rectory house had a cheese loft, cheese room, and dairy with nine cheese vats. (fn. 325) Prayers for the health of cows and horned cattle were said in church in the 1740s. (fn. 326) Cattle, pigs, and horses were allowed into the common meadow after mowing, policed by two wardens or 'drivers' appointed in the manor court. Pigs were banned from all commons between Michaelmas and All Hallows, however, thus protecting autumn herbage, while beasts of burden were excluded until 11 September. (fn. 327) In 1744 the parish constables paid a man for irrigating the common meadow and catching moles there. (fn. 328)

Four orchards mentioned in 1554 suggest small-scale fruit-growing, (fn. 329) and a great orchard' lay close to Brightwell Baldwin manor house in 1651. (fn. 330) William Spyer, yeoman, had orchard fruit worth 165. 8d. in 1660, and like several other farmers kept bees. (fn. 331) Woodland management is poorly documented, though in the 17th century the squire John Stone enlarged Ashley's wood with land inclosed from an open field in Britwell Salome, (fn. 332) and in 1776 two people were prosecuted for illicit felling in woods belonging to William Lowndes Stone. (fn. 333) Furze and fern were traditionally cut in the Grove, where some freehold tenants claimed furze allotments known as 'platts': in 1756 the platts were managed by three officers appointed in the manor court, and they were reorganized in 1789 when a new 15-a. platt was created for the poor. Only one man per family was allowed to cut fern, and then only after the feast of St Matthew (21 September) each autumn. (fn. 334)

Little is known about the size and tenancy of farms in the period 1500–1800. A few leases include one for a cottage and 23 a. in the open fields, granted for 21 years in 1635 with a covenant to provide one able man for the lord's wheat or barley harvest, or two days' labour in the year. (fn. 335) Cadwell (which lay outside the Brightwell estate until 1627) is marginally better documented: in 1609 the site of the manor was let for £2 115. annual rent and its other lands (130 a.) for £4 35. 4d., (fn. 336) and for much of the late 17th and early 18th centuries Cadwell farm was leased to the Pamplin family (fn. 337) John Pamplin (d. 1669) left goods worth £152, including £57 in crops (wheat, barley, peas, and maslin), and £33 in livestock (cattle, horses, sheep, and pigs). (fn. 338) Comparable farmers included Robert Smith (d. 1631), with crops worth £100, and Edmund Lane (d. 1683), with harvested crops worth £107 and wheat in the fields worth another £100. (fn. 339) By the 18th century the principal holdings on the Brightwell estate were Uppertown, Cadwell, and Brightwell farms, for which Richard Spyer, Mary Bye, and Henry Saunders respectively paid land tax of c.£16, £9, and £7 10s. in 1785. (fn. 340) Between 1700 and 1800 all three farms acquired new or remodelled farmhouses, barns, and other outbuildings. (fn. 341)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

Inclosure of Brightwell's common land (c.1,300 a. of open fields, meadows, and heath) was carried out in 1802, under a private Act promoted by the squire William Lowndes Stone. Stone received all the new inclosures, save for 46 a. of glebe and 1½ a. awarded to two freeholders for lost furze-cutting rights. (fn. 342) Some of the inclosed land was thrown into the new Whitehouse and Grove farms, the former created around a 20-a. property on the Ewelme boundary purchased in 1803, (fn. 343) and the latter established in 1805 when Stone leased 277 a. of arable and heath in the south of the parish to his cousin William Lowndes, who built a grand farmhouse there (Brightwell Grove) and resided as gentleman farmer. (fn. 344) Lowndes made numerous improvements, grubbing up, burning, and ploughing c.100 a. of furze during his first winter on the farm, and converting the rest of the heath to tillage by the third year. He also invested in a threshing machine and established a four-course rotation of turnips, oats or barley, clover and vetches, and wheat, ploughing with oxen rather than horses. Soil fertility was maintained by a flock of 360 Southdown sheep. (fn. 345)

By the mid 19th century Grove farm (428 a.) had a new tenant, and had absorbed additional lands including a former smallholding at Upperton. Whitehouse farm had been enlarged to 173 a., of which all but 35 a. lay in Brightwell. Other estate farms were Brightwell (254 a.), Uppertown (232 a.), and Cadwell (164 a.), while Glebe farm (32 a.) was worked with Grove farm. William Francis Lowndes Stone retained 282 a. in hand, (fn. 346) and on his death in 1858 had £659-worth of farming and outdoor effects including livestock, (fn. 347) his trustees subsequently selling 267 timber trees (140 elm, 79 oak, 32 beech, and 16 ash). (fn. 348) The number and size of farms changed little during the later 19th century, but turnover of tenants was high, with few staying longer than a decade or two. (fn. 349) Lengthier tenancies included those of William Bulford of Grove farm and Thomas Saunders of Brightwell farm, who were the principal agricultural employers in 1851 and 1871: Bulford's workforce rose from 24 to 32, with Saunders' falling very slightly from 17 to 16. Cadwell farm, rented by a Chalgrove farmer in the 1850s, was temporarily downgraded to labourers' accommodation, although in 1871 it and Uppertown farms employed 10 and 11 workers respectively (fn. 350)

A balance of arable, meadow, and pasture was maintained, although from 1866 to 1896 the area under cereals (wheat, barley, oats, and rye) increased from 455 a. to 548 acres. Head of cattle rose from 107 (none in milk) to 215 (including 63 milch cows), and numbers of pigs from 26 to 165, while conversely sheep numbers fell from 1,501 to 471, suggesting that the tradition of folding them on the arable was dying out. (fn. 351) Watercress was grown commercially from c.1860, at first by the Honey family, and later also by the Smiths: (fn. 352) in 1910 the beds in Brightwell Baldwin village and Cadwell covered 1½ a., (fn. 353) and by the 1920s the farmer at Cadwell was also a producer. During the following decade his successor delivered cress to Watlington station for onward transport to London, but the trade declined after the Second World War. (fn. 354)

In 1910 the Brightwell estates tenant farms were Grove (335 a.), Brightwell (321 a.), Uppertown (285 a.), Whitehouse (202 a.), and Cadwell (156 a.), while the rector Hilgrove Coxe farmed the 44-a. Glebe farm directly (fn. 355) From the 1920s it was let as a smallholding. (fn. 356) In 1924 the tenant of Whitehouse farm dealt in corn and manure, (fn. 357) and in 1926 a third of agricultural land (538 a.) was under cereals (wheat, barley, and oats), with a half (783 a.) under grass. Of that, 506 a. was for grazing and 277 a. for mowing. Cattle, sheep, and pig numbers were substantially unaltered from 1896, and poultry numbered 1,179. (fn. 358) Little had changed by 1941, when seven farms employed 26 workers between them. All the farms remained mixed and each had a cattle herd, although sheep were present only on Brightwell and Cadwell farms. Pigs were most numerous on Grove farm (with 58), and there were additionally two small poultry concerns. (fn. 359) Mushrooms were grown commercially on Brightwell farm in 1942. (fn. 360)

The 1940s-5os saw a change in ownership of every farm in the parish, as the Brightwell estate fragmented and the bulk of the glebe was sold. Most farms were purchased by tenants, although the bulk of Uppertown farm (c.280 a.) became attached to a large farming business run from Britwell Prior. A mixed farm at Brightwell Park was run by R.N. Richmond-Watson, who kept a herd of pedigree cattle and worked c.140 a. in and around the parkland. (fn. 361) Whilst the acreage under cereal crops in 1956 remained broadly the same as in 1926, cattle numbers rose to 311 as dairying and stock-herding became more important. (fn. 362) At least two farmers in the 1950s also grew sugar beet, transported from Watlington station. (fn. 363)

Increasingly Brightwell's farmland was worked from farms outside its boundaries, so that whereas in 1956 eight holdings in the parish worked nearly 1,200 a. between them, employing nine people full-time and one part-time, by 1988 only 314 a. was worked from Brightwell's five remaining farms, employing five part-time workers. (fn. 364) Brightwell farm was worked by a resident farmer who in the mid 1980s kept 40–50 beef cattle, but had recently ceased dairy production. (fn. 365) Beef cattle were also reared on Brightwell Park farm from the mid 20th and into the early 21st century, (fn. 366) while Cadwell Farm became the centre of a large-scale arable farm covering 1,200 ha (2,965 a.) in various parishes. (fn. 367)

MILLS, TRADES, AND RETAILING

In 1086 the future Parks manor included a watermill worth 2od. annually (fn. 368) Possibly it stood on the stream running north from Brightwell Baldwin village, where Geoffrey Langley obtained permission from the abbot of Dorchester to build a watermill in 1248. Presumably that was the 'new mill' for which Langley's son Geoffrey owed rent in 1279, (fn. 369) but no further record of a mill has been found, and probably Brightwell's corn was ground at neighbouring sites such as Cuxham's Cutt Mill.

A few tenants brewed beer in 1279, while occupational surnames included tailor, smith, and potter (crok). Walter Smith was a blacksmith, occupying a holding on Huscarls manor by service of shoeing the front hooves of two draught animals and repairing the lord's plough. (fn. 370) Later family members evidently continued the trade, and John Smith held 'le Smythous' (presumably a smithy) in 1371–2, besides acquiring holdings elsewhere. (fn. 371) A Brightwell butcher bought three cows and a heifer in 1309–10. (fn. 372)

Brightwell Baldwin village street c.1900, looking east. The forge (closed in the 1930s) is in the left foreground, with Brightwell Farm opposite.

By the 16th and 17th centuries the Smith family worked as wheelwrights, (fn. 373) and several carpenters were recorded, of whom one helped repair the kings mill at Ewelme in 1548. (fn. 374) Another in 1660 left beech and ash poles worth 145., an oak pole and hop poles worth 175., and a parcel of brush faggots valued at £1. (fn. 375) A tailor died c.1582, (fn. 376) and a mason and shoemaker were named in 1661. (fn. 377) The blacksmith Henry Newell died c.1681 leaving moveables worth £142, including £33-worth of 'iron, coals, tools, and nails' in his shop, and £61 'due upon the shop book. (fn. 378) The family continued as smiths until the 1840s, (fn. 379) perhaps at the Old Forge on the village street, which dates from the mid to late 18th century. (fn. 380) In 1731 a Brightwell man was licensed to practise surgery, (fn. 381) and two dealers were fined in 1757 for forestalling the Oxford market. (fn. 382) A pub (probably the later Lord Nelson) was licensed by 1753. (fn. 383)

In 1831 only 15 out of 95 adult males in Brightwell were employed in retail and crafts, the rest working mostly in agriculture. (fn. 384) Commercial premises in 1833 comprised two public houses, two grocers shops, a forge, and a bakery: (fn. 385) of those one of the grocers shops was in Upperton, which later acquired a boot-and shoemaker. (fn. 386) Members of the Goode and Coles families worked as thatchers in the 1840s, (fn. 387) while the forge passed to William Huggins, a master blacksmith who employed one man and two apprentices in 1851, and in 1854 also worked as a grocer. (fn. 388) Both the forge and Upperton's grocers shop continued into the early 20th century, the former closing in the 1930s, and the latter moving to the former Lord Nelson pub in Brightwell after 1905. (fn. 389) By 1924 the shop also housed the post office, (fn. 390) and in the 1950s both moved to a cottage on the village street, (fn. 391) before closing in 1985. (fn. 392) The Lord Nelson reopened as a pub in 1971. (fn. 393)

Gravel Extraction

A gravel pit mentioned in 1635 was perhaps west of Upperton, where a pit was being worked in 1802. (fn. 394) Some of the parish's poor were set to work there in 1835, and a man was killed in the pit in 1886. (fn. 395) In the 1850s and still in 1942 the owner of the Brightwell estate ran it directly, and in the latter year (when it covered 2 a.) it was said to contain a large quantity of gravel suitable for road- and path-dressing. (fn. 396) By 1960 it was disused, (fn. 397) but commercial extraction recommenced from 1968 until the mid 1970s, when the site was used for landfill. (fn. 398)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages Brightwell formed a typical rural community of free and unfree tenants, occupying varied-sized holdings on its two (and later three) main manors. Cadwell was much smaller, comprising little more than a single dwelling in 1086 and again from the later Middle Ages. Nonetheless it, too, supported a moderately sized community of mostly unfree peasants for much of the 13th and 14th centuries. A few 13th-century surnames suggest small-scale immigration into the parish from sometimes distant places. (fn. 399) Local lords were probably often resident during the earlier Middle Ages, the Salveyns at the moated site in Cadwell, and the Parks in Brightwell village, while the Bereford manor house (within the modern Brightwell Park) may have formed a sizeable complex, which in 1397 included a private chapel. (fn. 400) The Salveyns' long-running disputes with the Foliots over lordship of Cadwell in the 13th century (fn. 401) may have had marked local impact, and highlight the complex subletting and subinfeudation which characterized the whole parish.

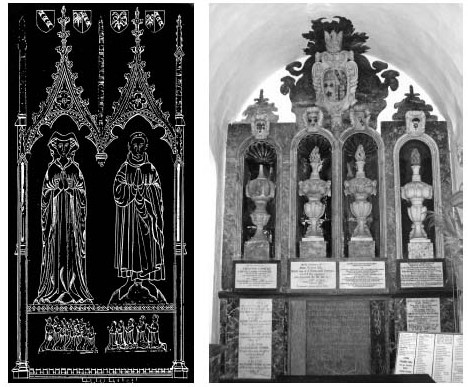

Freeholders, though in the minority, were important in local society: in 1279 Richard Binewale had ten subtenants, while the Langleys' sizeable holding was already emerging as a separate manor. (fn. 402) The wealthiest early 14th-century taxpayers were the lord Thomas Huscarl (paying 8s. 3d.) and the abbot of Dorchester (6s. 4d.), but the second highest in 1306 was the freeholder Geoffrey Blome, whose probable descendant John Blome (of Great Kimble, Bucks.) held over 100 a. in Brightwell, Ewelme, and Benson at his death in 1357. Thomas le Wedue of Cadwell was taxed in 1327 at a higher rate (7s. 2d.) than his lord John Salveyn (4s.), while high taxpayers in Brightwell included Richard Smith (5s. 6d.) and Richard 'atte Churcheye' ('at the churchyard') (4s. 3d.). (fn. 403) Both families were established by 1279 (the former as blacksmiths), (fn. 404) and the Smith family remained prominent beyond the medieval period. John Smith, who in 1371 held lands in Brightwell and Chalgrove, appears to have prospered by buying up vacant tenements after the Black Death, and is remembered in a memorial brass in the church with a rare Middle English inscription. (fn. 405)

Despite changes wrought by 14th-century plagues, most of the leading late-medieval tenantry came from established families including the Smiths, Walkelyns, Haleys, and Brians. (fn. 406) John Smith of Upperton served as a juror in the Oxford session of the peace in 1398, (fn. 407) while John Walkelyn was an Oxfordshire tax collector in 1442. (fn. 408) The only resident 15th-century lords appear to have been the Cottesmores, who played a dominant role, leaving prominent memorials in the church, and in 1502 attempting to seize the advowson. (fn. 409) As prominent gentry they also maintained close links with their peers, Thomas Stonor (of Stonor Park) obtaining wardship in 1470 of John (III) Cottesmore, who later married Stonor's daughter. (fn. 410)

1500–1800

The Cottesmores continued as resident lords into the early 16th century, William Cottesmore (d. 1519) leaving 12d. to every householder 'whether poor or rich'. (fn. 411) Sir Adrian Fortescue, owner of Parks manor, latterly also resided, (fn. 412) perhaps at the Cottesmores' manor house, and in 1538 reportedly brought his first wife's remains from Bisham priory (Berks.) for reburial at Brightwell. (fn. 413) From 1554 the two manors were combined under Anthony Carleton, whose widow Joyce was the parish's wealthiest taxpayer in 1581 with lands worth £10. Next wealthiest was Florence Alnot, a widow with goods worth £9. (fn. 414)

Lords' memorials in Brightwell Baldwin church. Left: brass to Sir John Cottesmore (d. 1439), his wife Amice, and their eighteen children. Right: the Stone family memorial, erected c.1670 by John Stone (d. 1704).

Joyce Carleton again paid the highest amount in a parish rate for communion bread in 1587, closely followed by Ralph Spyer 'of Kents' and Richard Smith 'of the Pond'. (fn. 415) Both came from particularly prolific Brightwell families, where topographical suffixes were commonly used to distinguish similarly named individuals. (fn. 416) The majority of inhabitants remained farmers and agricultural workers of varying wealth. Those with probate inventories valued at more than £200 in the period 1593–1733 included Richard Deane (d. 1661), a yeoman who left a parish charity and was buried in the chancel (£856 3s., including £780 in bonds). The farmers Edmund Lane (d. 1683), Robert Smith (d. 1631), and William Hester (d. 1672) each left personalty of over £360, while Frances Wade (d. 1701), a widow who may have kept an alehouse (below), left £230 including £150 owed her. (fn. 417) Over all, 23 individuals (35 per cent) left goods worth £100-£200, 12 (18 per cent) £50- £100, and 25 (38 per cent) under £50. (fn. 418)

The 17th century brought a mix of resident and non-resident landowners and clergy. Sir Dudley Carleton (d. 1632), viscount Dorchester, spent little time in Brightwell, (fn. 419) although his sister-in-law Mary married the rector William Paul in 1632. (fn. 420) Joseph Blackerby (d. 1672) arrived in 1648 as steward to the absentee lord Sir George Carleton, (fn. 421) and in 1665 was one of three inhabitants with houses taxed on four hearths. Most had only 1–3, save for the rector (14 hearths) and the then-resident squire John Stone (28 hearths). (fn. 422) The musician and composer William Hine (who became organist of Gloucester cathedral) was born in the parish in 1687, (fn. 423) and the following year saw the burial of a parishioner at the reputed age of 105, who had come to Brightwell from Chilton (Bucks.) as a teenager. (fn. 424) The Civil War had little documented impact despite a significant battle at neighbouring Chalgrove, (fn. 425) although in 1644 30 qrs of corn were demanded from Brightwell for the Royalist garrison at Oxford. (fn. 426)

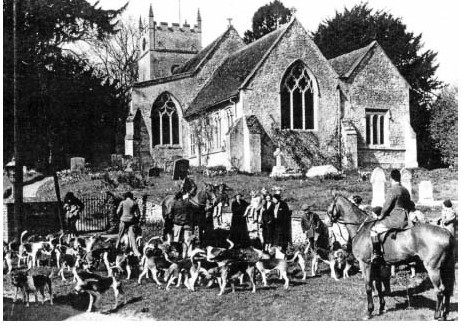

In 1677 the parish had had no alehouse in living memory, (fn. 427) but Frances Wade probably ran one in 1701 when she owned brewing equipment together with barrels, bottles, pewter ware, and plates and trenchers. (fn. 428) A pub licensed by 1753, probably the later Lord Nelson opposite the church, (fn. 429) hosted the manor court in 1756. (fn. 430) Other social activities included cricket (recorded from 1738), (fn. 431) an annual parish feast held on the Monday nearest St Bartholomews day (24 August), (fn. 432) and exclusive events at the manor house, such as Francis Lowe's entertainment for local Tories in 1753. (fn. 433) William Lowndes Stone (d. 1830) enjoyed hunting, and employed a gamekeeper, huntsman, and whipper-in at Brightwell in 1780. (fn. 434) Portraits of him and his wife Elizabeth were painted by Thomas Gainsborough c.1784 and c.1775 respectively. (fn. 435)

Servants and the poor become increasingly visible after 1600. Some 'poor wandering people' sheltered in a barn in 1644, and two gypsy children were buried in 1759, (fn. 436) while in 1741 a Brightwell man sought admission to Ewelme almshouse. (fn. 437) Lack of decent clothing was said a few years later to deter some parishioners from attending church. (fn. 438) Several 18th-century lords made bequests to servants (sometimes as much as £30), (fn. 439) and in 1729 John Stone paid for his servant Margaret Wiles to be buried in the church's north aisle. (fn. 440) A gardener, presumably employed at the manor house, was recorded in 1706, (fn. 441) and successors cultivated the walled garden constructed at Brightwell Park in the mid-to-late 18th century (fn. 442) Catherine Lowndes Stone's servants in 1780 included a butler, footman, coachman, and postilion, whilst her son William employed a butler, footman, gardener, and coachman. (fn. 443)

Following the fire that destroyed the manor house in 1788 three labourers working for William Lowndes Stone were arrested on suspicion of stealing wine from his cellars, (fn. 444) and in 1797 the communion plate was stolen from the church. (fn. 445) Petty criminals were sometimes detained by the parish constables, who throughout the 18th century maintained a set of stocks and made occasional payments for whipping miscreants. (fn. 446)

1800–1900

Throughout the 19th century Brightwell Baldwin remained a 'closed' community, with most land and housing belonging to the Brightwell estate. (fn. 447) William Lowndes Stone built estate cottages at Upperton in 1801, and the following year promoted the parish's inclosure. (fn. 448) His cousin William Lowndes, who built the outlying Brightwell Grove at his own expense, (fn. 449) was chief commissioner of the board of taxes, steward of the honor of Ewelme, and a close friend of William Pitt the younger, besides farming at Brightwell Grove farm. His house was taken over before 1822 by William Francis Lowndes Stone, who moved to Brightwell Park following his father's death in 1830. Thereafter Brightwell Grove was leased. (fn. 450)

The Lowndes Stones remained at Brightwell Park until 1858, employing twelve live-in staff in 1851. (fn. 451) Hunting remained central: William Lowndes Stone maintained stabling and kennels and employed a long-serving gamekeeper and huntsman, William Phelp (d. 1828), whose portrait (depicting him on his pony amongst the hounds) was painted in 1812. (fn. 452) The South Oxfordshire Hunt still met regularly at Brightwell Park in the late 19th and 20th centuries (Fig. 30). (fn. 453) In 1847 the family suffered a double tragedy when scarlet fever killed two generations of male heirs on consecutive days, (fn. 454) and after the estate passed to William Francis Lowndes Stone's granddaughter the family lived elsewhere. A core estate staff was retained, however, (fn. 455) and in 1874 four houses were built in Cuxham to accommodate Brightwell servants. (fn. 456) Nineteenth-century tenants of Brightwell Park included Frederick Austen (c.1858–68) and Albert Sandeman (c.1876–86), (fn. 457) a port and sherry producer who became governor of the Bank of England and served as vice-chairman of the Brightwell School Board. His wife was a frequent school visitor, distributing presents each Easter Monday, and in 1881 donating materials for new sets of clothes. (fn. 458)

The former Lord Nelson pub (then a shop and post office) in 1942. Recorded from the 1750s, it reopened as a pub in 1971.

Most parishioners in the 19th century were employed on the estates tenant farms, whose farmers or bailiffs often employed domestic as well as farm servants. Labourers and craftsmen still came mostly from the parish or nearby, although servants and tenant farmers were often from further afield. (fn. 459) The leading farmers usually served as parish officers, and in 1879 there was a stand-off when William Bulford of Grove Farm and others opposed a rise in church rates by refusing to nominate a peoples churchwarden. (fn. 460) Choice of a peoples warden caused further acrimony in 1900, with heated exchanges at vestry meetings attracting local newspaper coverage, and until 1907 the appointment had to be settled by an annual parish poll. (fn. 461)

Social life in the early 19th century revolved around the pub, called the Admiral (later Lord) Nelson by 1802 when a public inclosure meeting was held there. (fn. 462) The building (which belonged to the Brightwell estate) (fn. 463) was also used for manor court sessions (fn. 464) and for auctions of timber and crops. (fn. 465) A second public house, recorded in 1833, was apparently short-lived. (fn. 466) A parish room was built onto the end of a barn on glebe land fronting the village street in 1891, the £192 cost met in part by the rector, and from a bazaar held at Brightwell Park. It was subsequently used for parish and vestry meetings, and services were held there in 1895 when the church was being restored. (fn. 467) A parish cricket team existed by 1899, (fn. 468) when the schoolmaster taught horticultural classes in the parish room, and cooking demonstrations were given in a cottage under the title cottage cookery'. (fn. 469) Concerts were occasionally given at the school from 1898. (fn. 470) A highlight was the annual 'feast day' held usually in early September, presumably as a successor to the St Bartholomews day festivities. Activities included sports and a harvest tea. (fn. 471)

Since 1900

Few early 20th-century tenants of Brightwell Park stayed for long, exceptions being Edward Lauder-Watson (c.1914–28) and Sir Richard Gull, Bt (1928-38), who served as chairman of the parish meeting for nine years. (fn. 472) During the Second World War the house accommodated two evacuated preparatory schools for boys, one from Kingsbury (Middx) and the other from Lee-on-Solent (Hants), (fn. 473) and following the estates sale in 1942 most later owners of the house resided. Frank and Margaret Wright played leading roles in parish life, and quarter peals were rung in the church following their deaths in 1994 and 2000. (fn. 474) Their son-in-law Brigadier Nigel Mogg of Brightwell Park was deputy lieutenant of Oxfordshire in 1998 and high sheriff in 2002. (fn. 475)

The parish community changed little before the Second World War, comprising tenant farmers, labourers, and servants, with a few craftsmen and shopkeepers. (fn. 476) The rector Hilgrove Coxe (1890–1914) farmed Glebe farm as a hobby, and was a keen huntsman and follower of village cricket. (fn. 477) Six council houses were built in Upperton in the 1920s, however, (fn. 478) and further change followed the break-up of the estate. Fewer servants were retained, shops and workshops closed, and a greater number of incomers moved in, (fn. 479) while the school closed in 1961. (fn. 480) New housing was erected particularly at Upperton, where several bungalows were built in the 1960s, and as farming employment fell more inhabitants travelled outside the parish for work. (fn. 481) In 1980 the interior designer and author David Hicks (d. 1998) moved into the former farmhouse at Brightwell Grove with his wife Lady Pamela, daughter of Earl Mountbatten of Burma, creating a celebrated garden and remodelling the house to include a mural by Rex Whistler. (fn. 482) The Old Forge in Brightwell Baldwin village (converted from a blacksmiths shop before 1939) was bought in 2002 by the duke and duchess of Kent. (fn. 483)

Social life in the early 20th century still focused on Brightwell Park, where fetes and Sunday school treats were regularly held in the grounds. Edward VIIs coronation in 1902 was marked by cricket, sports, tea, and fireworks there. (fn. 484) The Lord Nelson pub closed in 1905 following complaints by the rector and squire about rowdy behaviour, becoming a grocer's shop, post office, and (later) a private dwelling before its reopening as a pub in 1971. (fn. 485) A recreation ground at Upperton was given by Roger Lowndes-Stone-Norton in 1912, (fn. 486) and was equipped with swings in 1954 to mark Elizabeth II's coronation. Allotments were established on part of it in 1985. (fn. 487) The cricket club, which had its pitch in the Brightwell Park parkland, was dissolved in 1962 when its remaining funds were given to the church, (fn. 488) but the parish room continued as a focus for meetings and social events. In 1955 it was bought from the church by the parish meeting for use as a village hall, but was later leased back to the church for a peppercorn rent. A youth club met there in the late 1950s, (fn. 489) other regular users including the Mothers' Union (later the Brightwell Baldwin and Cuxham Women's Fellowship, dissolved in 2007) and the Brightwell and Britwell Women's Institute (established in 1938 and suspended in 1985). (fn. 490) A community history and archaeology project begun in 2006 ran for several years, involving a number of residents. (fn. 491)

EDUCATION