Pages 69-88

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

BERRICK SALOME

The small and relatively scattered village of Berrick Salome occupies gently rising ground a mile or so north of Benson, its clunch-rubble and timber-framed buildings strung loosely along the Newington road and a few intersecting lanes amidst some small-scale modern infill. The place name (Anglo-Saxon berewic) reflects its origins as an outlier of the Anglo-Saxon royal estate centre at Benson, although ecclesiastically it became a chapelry of Chalgrove, reflecting manorial links established in the 11th century. For most civil purposes it was fully independent by the 17th century, and from the 19th it was counted a civil parish. (fn. 1)

The villages northern end merges with the hamlet of Berrick Prior, historically part of Newington parish. That and the hamlets of Roke and Rokemarsh, to the south, were absorbed into Berrick parish in 1992, the last two having been previously divided amongst Berrick Salome, Benson, and Ewelme. (fn. 2) Socially and economically they had close ties with Berrick considerably earlier. The suffix 'Salome', recorded from the 1520s, (fn. 3) imitated the similar pairing of nearby Britwell Salome and Britwell Prior, the medieval Sulham family (which gave Britwell Salome its name) (fn. 4) having no connections with Berrick. Occasionally the village was also called Nether or Lower Berrick, and in 1360 Berrick by Dorchester. (fn. 5)

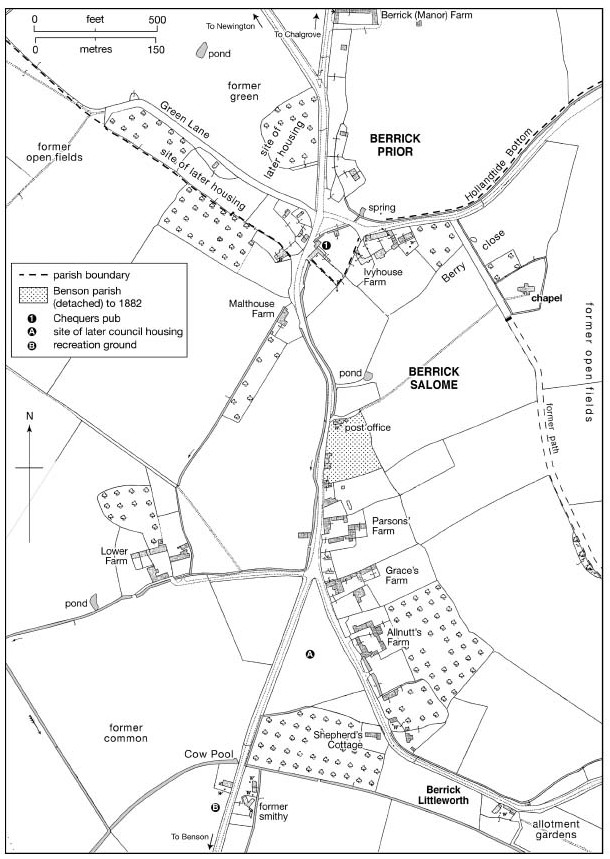

PARISH BOUNDARIES AND LANDSCAPE

Berrick's Anglo-Saxon connections with Benson were reflected in their shared open fields, which survived until inclosure in 1863. (fn. 6) Consequently there was no linear boundary between the two, the open-field strips which paid tithe to Berrick lying scattered as far south as Goulds Heath, though with a marked concentration in the Berrick area (Fig. 4 and Table 3). (fn. 7) The parish's more clearly defined western boundary with Warborough and its eastern one with Brightwell Baldwin both followed ancient routes, (fn. 8) while the northern boundary with Newington followed field divisions, a lane along the shallow valley of Hollandtide Bottom, and (within the village) property boundaries between Berrick Salome and Berrick Prior, which left the Chequers pub and some other buildings just outside the parish. (fn. 9) That last boundary was established when the settlements northern half was granted to Canterbury cathedral priory in the early 11th century, becoming (as Berrick Prior) part of Canterbury's Newington estate, and consequently part of Newington parish. (fn. 10) Roke's division between Berrick, Benson, and Ewelme parishes followed similar manorial divisions, bringing the hamlets western half (including Roke Farm) into Berrick, while three cottages fronting Berrick Salome village street remained part of Benson parish until 1882. In 1839 the parish was reckoned at 678 a., including (as with several neighbouring parishes) small areas of detached meadow in Drayton St Leonard. (fn. 11)

The boundaries with Benson and Ewelme were redrawn at inclosure, creating a parish of 600 a. which, reflecting earlier complexities, included seven small detached areas intermingled with parts of the other parishes. Rationalization in 1882 and 1932 reduced it to 557 a., (fn. 12) expanded to 729 a. (295 ha) by the absorption of Berrick Prior, Roke, and Rokemarsh in 1992. (fn. 13)

The village (at c.54–57 m.) and the parish's western part rest chiefly on low-lying floodplain alluvium, (fn. 14) which until inclosure provided a large tract of common pasture around which Berrick, Roke, and Rokemarsh developed. North-west and east of the village, areas of Gault Clay, Upper Greensand, and gravel underlie the former open fields, those on the east (where the ground rises to over 80 m.) formerly characterized by 'Hill' names. Local springs feed the small streams (most of them straightened and diverted at inclosure) which flow towards the Thames through the former commons, those through Berrick village and Roke flanking the main village streets. (fn. 15)

Looking north along Berrick Salome's main street, with Parsons' Farm and its barns on the right and Plough Cottage further along.

COMMUNICATIONS

Berrick lies along a now minor north-south road from Newington, (fn. 16) which in the Anglo-Saxon and medieval periods was probably more significant. To the south (beyond Roke) it meets the Watlington-Benson road at or near the probable hundredal meeting place, (fn. 17) and formerly it continued southwards along Tidmarsh Lane between Ewelme and Fifield. A branch leading south-westwards to Benson (formerly crossing the commons and fields) was mapped in 1638, and is presumably also ancient, although the stretch beyond Rokemarsh is now only a footpath. The villages northern end (adjoining Berrick Prior) lies near the Newington road's intersection both with the main Chalgrove road, and with the probable line of the Romanized Lower Icknield Way along Hollandtide Bottom and through to Warborough. (fn. 18) That latter route formed much of the northern parish boundary and, though only a minor lane in the 19th century, was still used by local farmers, despite the winter flooding and mud which sometimes affected Berrick's other roads as well. (fn. 19) East of the village street, a north-south lane skirting the open fields connected the church with the villages southern end, but like several other lanes across the fields was suppressed at inclosure. (fn. 20) On topographical grounds it may have once continued northwards to meet the Newington road, forming part of a continuous route southwards to Tidmarsh Lane and beyond.

Carriers based at Roke and elsewhere served the village intermittently from the mid 19th century to mid 20th, but by the 1960s (as in 2015) there was no public transport. Post was delivered through Wallingford by the 1850s, and a sub-post office in a Berrick cottage opened in the 1890s, continuing until the postmistress's death in 1949. Benson remained the site of the nearest money order and telegraph office. (fn. 21) A post office in the Chequers (still technically in Berrick Prior) operated in the 1960s–80s, (fn. 22) followed by a short-lived service in Berrick village hall. (fn. 23)

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

Prehistoric to Anglo-Saxon Settlement

An area of multi-phase occupation spanning the Neolithic to Roman periods has been excavated on the Berrick-Warborough boundary west of Berrick Salome village, adjoining a likely Roman road which the boundary follows. Activity there intensified during the late Bronze and early Iron Ages, but a subsequent rural Roman settlement was apparently abandoned after the Roman withdrawal, and the site absorbed into the later open fields. (fn. 24)

Archaeological evidence of Anglo-Saxon activity within the modern parish is so far lacking, but the place name Berrick (Anglo-Saxon berewic), recorded in 1086, suggests a dependent settlement or farm within the Benson royal estate, (fn. 25) to which the area certainly belonged. Presumably it was well established by the early 11th century, when its northern part (later Berrick Prior) was granted to Canterbury cathedral priory. (fn. 26) A separate land grant in 996, possibly relating to an area in the ancient parish's north-eastern corner, (fn. 27) suggests a tightly organized surrounding landscape, named features including 'headlands' as far as 'chalk-pit way', 'Bryda's tumulus', 'woad valley', a worth (or small settlement), named streams, and hedgerows. A 'fielden wood way' was probably Rumbold's Lane, marking the ancient parish's eastern boundary, and forming part of a route linking the vale with the Chiltern uplands. (fn. 28) The settlement's location was presumably influenced by the presence of the nearby springs, which emerge close to the junction of the gault and greensand, and which provided the village's water into modern times. (fn. 29)

Population from 1086

Twenty tenants (including 4 servi) were recorded at Berrick Salome in 1086, and 21 in 1279, (fn. 30) suggesting a population approaching 100. For the period the figures imply unusually small population growth, although some tenants may have been omitted from the 1279 survey. (fn. 31) In 1377, after the Black Death, poll tax was paid by 59 inhabitants over the age of 14, (fn. 32) still implying a population of at least 100, and in 1462–3 (despite some amalgamation of holdings) 18 customary tenants in Berrick and Roke were listed on just one half of the manor, alongside a few possibly resident freeholders. (fn. 33) In 1523–4, when c.10 inhabitants paid tax, Berrick remained amongst the hundreds smaller settlements. (fn. 34) Hearth tax was paid in 1662 on 16 houses, probably excluding the few dwellings at Roke included in Berrick Salome parish, and possibly omitting a few others, since an adult population of at least 80 was estimated in 1676. (fn. 35) In 1738 the vicar reckoned that there were c.20 houses, (fn. 36) and in 1801 (following further population growth) there were 30 occupied by 37 families (143 people). That and later census figures included 4–5 houses at Roke, but omitted the similar number in Berrick Salome village which still belonged to Benson parish. (fn. 37)

By 1821 the population had risen to 174 in 30 houses, falling to 134 over the next ten years but recovering to 167 (in 37 houses) by 1841. Thereafter it fell gradually to 86 in 1891, and for the most part fluctuated around 100 until the 1970s, when new house-building raised it to 152 in 52 households by 1981. The subsequent incorporation of Berrick Prior, Rokemarsh, and Roke brought the parish population to 325 (in 125 households) by 2001, which was little altered ten years later. (fn. 38)

Village Development (fn. 39)

The shape and extent of the late Anglo-Saxon settlement is unknown, and was probably altered by 11th-century and later reorganizations. (fn. 40) Some houses, however, may have already lain along the modern street, fringing the large area of common pasture to the west, (fn. 41) with houses at what became Berrick Prior possibly clustered (as later) around a large green. (fn. 42) An early focus within Berrick Salome itself was presumably the chapel, founded probably in the 11th or early 12th century after Berrick Salome became a small independent manor. (fn. 43) By the 18th century it stood separate from the bulk of the village on the edge of the open fields, presumably reflecting settlement shrinkage. The lane running past it may have once formed part of a longer route, (fn. 44) and land adjoining was called Bury closes, perhaps recalling a nearby 11th-century manorial centre abandoned after Berrick was subsumed into Chalgrove manor. (fn. 45)

Berrick Salome and the southern part of Berrick Prior in 1919. (For fields see Fig. 4.)

The retention within Benson manor (and later parish) of a separate block of house plots on Berrick street may indicate that their site had some special early importance, although later they apparently comprised only ordinary tenant holdings. (fn. 46)

The location of known manorial copyholds, some of which can be traced from the 16th century, (fn. 47) suggests that medieval settlement spread along the whole length of the village on both sides of the street, from near Malt House in the north down to Shepherds Cottage near Berrick Littleworth - a name attached by 1861 to the villages southern edge near Roke. (fn. 48) Almost certainly such settlement was always loosely scattered, and probably it became sparser during the later Middle Ages. (fn. 49) Predecessors of Ivyhouse Farm and Ivyhouse Cottage, on the lane to the chapel, were possibly mentioned in 1382, (fn. 50) the latter remaining a manorial copyhold and the former a freehold. (fn. 51) Lower Berrick Farm, on the northern edge of the large former common just west of the street, is also associated with a late medieval freehold, and in its present form originated c.1550. (fn. 52) A cottage at Cow Pool on the Benson road, adjoining a stream on the commons edge, existed by the 17th century, (fn. 53) and in the 19th there was a nearby smithy and wheelwright's. (fn. 54)

The villages shape was little altered thereafter, although two farmhouses on the streets west side were demolished during the 19th century, followed by several cottages. (fn. 55) Piecemeal infilling began c.1949 with six council houses at Weller Close (between the Benson and Ewelme roads), (fn. 56) and from the 1960S-70S other houses were built to their north, on the Benson and Ewelme roads, on Berrick streets east side, and along the parish's northern edge on Green Lane (formerly in Berrick Prior). Some replaced earlier caravans. Modern farm buildings opposite Parsons' or Parsonage Farm were erected from the 1960s, and a children's playground was opened at the Benson road recreation ground (at Cow Pool) in 1966, followed in 1980 by an adjacent village hall. (fn. 57) Electricity was available by 1937 (fn. 58) and a small sewage works was built c.1950, (fn. 59) although water supply was still from wells and springs in the 1940s. (fn. 60) The outlying Hare Hall (formerly Brookslade Farm) was built in former open fields to the east of the village in the 1880S–90s. (fn. 61)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Berrick's older domestic buildings comprise cottages and modestly sized former farmhouses of mostly 16th-to 18th-century date, built chiefly of local clunch rubble, but with a handful of timber-framed dwellings which were probably once more numerous. (fn. 62) Roofs are thatched or tiled, although much thatch was lost during the 20th century (fn. 63) Brick is mostly confined to chimney stacks and occasional dressings and quoining; exceptions (besides the 18th-century Chequers pub in Berrick Prior) include the main range of Ivyhouse Farm, fronted in Flemish-bond brick with flared headers, and bearing the scratched date 1781, when it was a tenanted farmhouse. Like most buildings it retains casement windows, and its through-passage plan suggests earlier origins. (fn. 64)

The highest-quality farmhouse is Lower Berrick Farm (Fig. 20), whose western part incorporates a timber-framed house built c.1550 probably for the Hambledens, Berrick's wealthiest yeoman farmers. The hall had a chimney from the outset, and a clunch-built rear stair tower may be contemporary. A storeyed parlour range was added on the east c.1613, and the remainder was encased in clunch with brick dressings, acquiring a semi-symmetrical row of four gabled dormers. (fn. 65) In 1662 it was the parish's largest house, taxed on six hearths. (fn. 66) Other former farmhouses (all 17th-century or earlier) include Parsons', Grace's, Allnutt's, and Malt House, former copyholds named mostly from 18th- or 19th-century tenants. (fn. 67) Parsons' (now misnamed Parsonage Farm), aligned along the southern edge of its former farmyard, comprises a single clunch and flint range of one storey with attics, formerly thatched, and extended lengthways in the 17th or 18th century (fn. 68) Allnutt's, rubble-walled and two-storeyed with attics, has a three-unit lobby-entry plan, while nearby Graces has a two-unit plan with a double rear wing, and an added 19th-century block with a canted bay window. Its interior retains five brick fireplaces including three with Tudor arches, an open-well stair with knob finials and a roll-moulded handrail, 17th-century panelled doors (one dated 1655), and two corbels dated 1663. (fn. 69) Sizeable farmyards formerly adjoined most farmhouses, sometimes on a courtyard plan: surviving structures include a timber-framed granary at Ivyhouse and a similar granary and cowhouse at Lower Farm, (fn. 70) which in 1754 had two barns, two stables, a pigeon house, and a wood-house. (fn. 71) Farm buildings generally were still predominantly thatched in 1910, although corrugated iron was already appearing. (fn. 72)

Lower Berrick Farm from the south, showing the remodelled, formerly timber-framed 16th-century range on the left (between the chimney stacks), and the addition of c.1613 to the right.

Smaller houses include the three-bayed Old Post Office and Little Frogs, both timber-framed and single-storeyed with attics. (fn. 73) Several houses of similar or smaller size (some flimsily constructed) were demolished in the 19th or early 20th centuries, (fn. 74) and were presumably common in the 1660s when 37 per cent of houses were taxed on only one or two hearths, and 81 per cent on fewer than four. (fn. 75)

New 20th-century houses, some plain and others incorporating vaguely 'vernacular' features, display a variety of materials including brick, render, stone, and timber-cladding, while in the 1980S-90S several redundant farm buildings were rebuilt or converted to domestic use, notably at Parsons' and Grace's Farms. The village became a conservation area in 1984. (fn. 76)

MANORS AND ESTATES

Though Berrick Salome formed an independent estate by 1066 it was subsequently absorbed into Chalgrove manor, with which much of it passed in the late 15th and early 16th centuries to Magdalen and Lincoln Colleges, Oxford. Both retained their Berrick property until the 20th century. Lords of neighbouring Ewelme and Fifield owed quitrents for lands in Berrick in the 15 th century, (fn. 77) and numerous freeholds included one occasionally called a 'manor', while tithes and some small parcels of glebe belonged from the Middle Ages to the rector (and later vicar) of Chalgrove. Around half the parish's land was still under non-collegiate ownership in the 1830s. (fn. 78)

EARLY ESTATES AND CHALGROVE MANOR

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Berrick belonged to the royal estate of Benson. (fn. 79) Two hides granted in 996 to the brothers Eadric, Eadwig, and Ealdred, described as 'king's men', may have lain in the ancient parish's north-eastern corner, (fn. 80) but if so they apparently reverted to royal ownership. (fn. 81) The settlements northern part, however, was granted to Canterbury cathedral priory with Newington in the early 11th century, and (as Berrick Prior) remained in separate ownership thereafter. (fn. 82)

By 1066 the rest of Berrick, rated at 4 hides, was held of the king by Ordgar, who had succeeded his father and uncle. The estate was held with Gangsdown in Nuffield, making a standard 5-hide unit. By 1086 Ordgar held under the prominent Norman baron Miles Crispin, and Berrick (along with Gangsdown and attached holdings in Roke) was subsequently absorbed into Miles's manor of Chalgrove. (fn. 83) At Chalgrove's division in 1233 and 1356 the Berrick and Roke holdings were apportioned amongst Chalgrove's various lords, with a few properties held in common. (fn. 84)

In 1485–7 the Barentin and Argentein shares of Chalgrove manor were acquired by Magdalen College, Oxford, and in 1507–8 the smaller St Clare's share passed to Lincoln College. (fn. 85) Both acquisitions included holdings in Berrick Salome and Roke, (fn. 86) which were formally partitioned amongst the colleges and George Pudsey (as owner of Chalgrove manor's remaining part) in 1570. (fn. 87) Magdalen's holdings were increased by piecemeal purchases in the 1520s–30s and 1569–70, (fn. 88) and by 1833 it owned 193 a. in Berrick Salome parish compared with Lincoln's 65 a., all of it let to tenants. (fn. 89) Pudsey's share passed with his Chalgrove manor to the Winchcombe and Hall families, but by the 1780s had apparently been broken up. (fn. 90) At inclosure in 1863 Magdalen received 270 a. for its combined estates in Berrick, Roke, and Benson, (fn. 91) and following purchases in 1884–5 and 1900–1 it held over 700 a. in the three places. (fn. 92) Its Berrick estate (latterly 596 a.) was sold to the tenant A.M. Hoddinott in 1970, and Roke farm (192 a.) in 1986, (fn. 93) while Lincoln College's Parsons' farm (then 75 a.) was sold to the tenant in 1943. (fn. 94)

Lordship was still shared between the colleges in 1863, (fn. 95) though from the 1850s local directories named the Blounts of Mapledurham as lord, presumably as owners of the former Pudsey estate in Chalgrove. (fn. 96) In 1995 the sale of Magdalen's Chalgrove lordship to the Jacqueses of Chalgrove Manor was deemed to include that of Berrick Salome, though with no exercisable rights. (fn. 97) A few small quitrents to Benson manor remained payable in the late 18th century, while a perambulation in 1826 still included Berrick within the alleged bounds of Benson manor. (fn. 98)

FREEHOLDS AND 'BERRICK MANOR'

Freeholds accounted for at least half the manorial land by 1279, when the largest (2 yardlands) was held by Walter of Roke (del Ok'). (fn. 99) The only traceable estate, however, is an accumulation focused probably by the 16th century on Lower Berrick Farm, which seems to have derived in part from a substantial freehold in Chalgrove, Berrick, Roke, and elsewhere owned in 1314 by John Marshall of Bovingdon Green (Bucks.) and his brother Thomas. (fn. 100) In 1336 they held a house and 62 a. in Berrick partly by military tenure, (fn. 101) but by 1343 they were in debt, and in 1361 the holding was confirmed to Sir Hugh of Berrick (d. 1403), passing through marriage (with Hugh's Buckinghamshire lands) to the Butler or Botiler family of Badminton (Glos.). (fn. 102) In 1422 and 1477 it was called Berrick manor, (fn. 103) and in 1542 John Butler esq. sold it as such to Laurence Hanford of Beaconsfield (Bucks.), with a nominal 200 a. of arable, 160 a. of meadow, pasture, and heath, and 6s. 8d. rent in Berrick and Warborough. (fn. 104) Quitrent payments suggest that the tenancy (and eventually the ownership) remained with prominent Berrick yeomen, including (by 1503) John Smith, by 1550 the Hambledens, and in 1672 the Barretts, (fn. 105) who in 1731 sold to the Blackalls of Wallingford and Berrick. They expanded the estate (still occasionally called a manor), which in the late 18th century passed through marriage to the Musgraves of Barnsley Park (Glos.). (fn. 106) In 1834 it was sold to the London lawyer John Smart, who in 1839 owned Lower Berrick Farm with c.94 a. and a cottage, and a similar acreage in Berrick Prior, all let to tenants. (fn. 107)

By then non-college lands in Berrick covered 232 a. (50 per cent of occupied land), the other chief owners being the Powells and Hutchinses of Benson (42 a. and 30 a. respectively), and the prominent Roke farmer Thomas Weller (30 a.). Powell's holding included Ivyhouse farm. Around 25 owners were recorded in all, many with only a few odd acres, while the largest holdings were all let to tenants. (fn. 108)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until inclosure in 1863 Berrick shared an open-field system with Benson and Ewelme (Fig. 4), including access to grazing and meadow (fn. 109) In 1839 surrounding land was 'of very strong quality' with 'a good depth of soil over a very stiff clay', yielding good grain crops 'to those who go to the expense and trouble of working them well'. (fn. 110) Like most neighbouring places the village generally pursued arable-based mixed farming, supporting sheep, cattle, and dairying as well as wheat and barley production. Farming benefited from accessible markets, and remained dominant until the 20th century: traditional trades and crafts were recorded only sporadically, although a malthouse operated by the 1760s, and in the 19th century there were generally a couple of small shops.

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

Berrick's name suggests a specialized outlying farm within Benson's large late Anglo-Saxon estate, (fn. 111) but by 1086 it formed an independent 4-hide manor with a conventional agricultural community. Ten villani and 6 bordars had 3 ploughteams between them, and another two teams (worked partly by 4 slaves or servi) were employed on the lord's demesne. Since the manor reportedly had land for only four teams it may have been over-cultivated, although its annual value had risen from £3 to £4 since 1066. Additional resources (probably in demesne) included 4 a. of meadow, 2 a. of pasture, and woodland measuring 2 furlongs by 1 furlong. (fn. 112) The latter was perhaps recalled in the later field-name Woodlands (east of Berrick village), (fn. 113) or may have lain outside the parish on the Chiltern uplands.

By 1279, when Berrick formed part of Chalgrove manor, the demesne had been reduced to 6 yardlands (c.120–150 a.) and was let to tenants. Just over half was held in common by nine resident villeins for 1105. 3d. a year, local freeholders occupying the rest in parcels of ½ or ¾ yardlands. The villeins' share included demesne farm-stock comprising 6 oxen, 2 draught animals, 200 sheep, a hayrick, and 27½ a. of sown land, together with tenants' brewing tolls and pannage payments. Clearly the arrangement was of long standing, since the king ordered an incoming lord to respect it in 1228. In addition, a total of 15 villeins (including the demesne lessees) occupied more conventional customary holdings ranging from ¼ yardlands (effectively cottage holdings) to whole yardlands: most occupied ½ yardlands (c.10–12½ a.) for 35. rent, supplemented by light harvest, hoeing, and wood-carrying services on the lords' Chalgrove demesnes. A few held additional land, and five freeholders occupied 1–2 yardlands each for varying rents. (fn. 114) In all the 1279 description accounted for 18 yardlands, but was apparently incomplete. A survey of one half of Chalgrove manor in the 1460s listed 20½ Berrick yardlands held by 18 customary tenants, excluding some sizeable freeholds. (fn. 115)

By 1336 some villein rents on the Plessis manor were substantially heavier than those reported earlier, although most Berrick villeins still occupied only ½ yardlands, and a few cottagers paid 1s.–2s. each. Villein labour services (valued at 145. 10¾d. a year) were apparently still exacted, and the manors combined income from Berrick totalled c.£6.15s., chiefly in customary rents. Two tenants each held c.9–12 a. of demesne for additional rent, and small demesne meadows at Drayton and Shillingford were similarly leased; otherwise the former Berrick demesne was no longer discernible. (fn. 116) A separate freehold known sometimes as 'Berrick manor', containing at least 4 yardlands, was let to Richard Wiggin for 7 years in 1422, at 46s. 8d. a year. (fn. 117)

Late medieval depopulation at Berrick seems to have been relatively limited, (fn. 118) and unusually rental income during the late 14th and 15th century held fairly steady and possibly even increased. (fn. 119) Nevertheless the village saw the accumulation of holdings typical of the period. Three customary tenants in 1462–3 held at least two yardlands (40–50 a.), and one (Robert Digweed) held four, while the double-yardlander Thomas Vynt was sufficiently prosperous in 1476 to co-rent part of the Chalgrove tithes for 53s. 4d. a year. (fn. 120) Freeholds were possibly also combined: holdings of up to 21 a. changed hands in the early 16th century, while the reputed 'Berrick manor' (still leased to tenants) remained much larger. (fn. 121) Labour services were presumably long commuted by the 1460s, when the Chalgrove demesnes were leased. Nonetheless five Berrick tenants still owed nominal harvest works valued at 6s. in all in 1462–3. (fn. 122)

Throughout, tenants' open-field cereal production was presumably combined with pastoral farming, including sheep-rearing as in the Berrick demesne lease. John Cotterell's sheepfold needed repair in 1497, and in 1486 John Benet of Roke (who held land from Benson's Fifield manor) was fined for over-burdening Berrick's pastures with 400 sheep. (fn. 123) Tenants' cows and pigs were mentioned occasionally, (fn. 124) and some rents were paid partly in poultry (fn. 125)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

The sale of much of Chalgrove manor to Magdalen and Lincoln Colleges had little impact on Berrick's tenancies or farming, both institutions taking over existing manor courts and granting copyholds for two or more lives. (fn. 126) In 1508 their combined Berrick and Roke estates totalled 19 yardlands with a few additional parcels and cottages, divided amongst c.14 leading tenants. John Cotterell held 4¼ yardlands partly in Roke, while other large tenants included William Cooper and members of the Wise and More families. (fn. 127) Freeholders included Henry Spindler (at Roke) and John Smith (d. 1534), who held the 'Berrick manor' freehold and in 1523–4 was Berrick's wealthiest taxpayer, paying 405. William Spindler paid 7s., and the Wises, Viccarys, Mores and Cot3terells between 1s. 6d. and 3s. each. (fn. 128) A few small freeholds (including some Spindler land) were subsequently sold to Magdalen, (fn. 129) but otherwise the pattern was little altered in the 1580s when the wealthiest taxpayer was Smith's successor William Hambleden (assessed on goods worth £10), followed by Thomas Spindler (£5) and the Viccarys, Wises, Talbots, and Mores. (fn. 130)

Contemporary wills suggest the mixed farming typical of the area, focused on wheat, barley, and pulses, with some dairying and sheep-rearing on a moderate scale. Cows, pigs, poultry, and bees were mentioned frequently, some hemp was grown, and most larger farmers were well equipped with ploughs, carts, and horse-teams. (fn. 131) Scarcity of wood may have prompted four leading tenants to cut down trees without permission in 1504, although timber for repairs was allowed by manorial custom. (fn. 132)

The 17th and 18th centuries saw little major change, with relatively modest increases in most farm sizes and continuation of both copyhold tenure and open-field farming. The Hambledens (probably of Lower Berrick Farm) remained by far the wealthiest farmers in the mid 17th century, when John Hambleden (d. 1672) left goods worth over £1,100 including 137 sheep, 22 cattle, 14 pigs, 911 cheeses, large quantities of wheat and barley, some maslin, pulses, and oats, and £350 cash. (fn. 133) His freeholds passed to the Berrick yeoman John Barrett (a relative), who combined them with the copyhold Roke farm (later 68 a.). (fn. 134) Most yeomen left more modest sums of c.£50– £260, (fn. 135) and apparently retained more modest farms: in 1678 Magdalen had nine copyholders still including the Mores and Wises, with some of its largest holdings probably focused (as later) on Grace's and Allnutt's Farms, Ivyhouse Cottage, and a later demolished farmhouse west of the village street. (fn. 136) Lincoln College's four copyholds (focused on the later Parsons' and Malt House Farms, Shepherds Cottage, and a house opposite Parsons') remained between 5 a. and 25 a. (¼–1¼ yardlands) c.1771, (fn. 137) although most (like some Magdalen farms) were sublet or occupied with other land. Parsons' in particular was held by James Kemp (d. 1782) of Benson and Roke, a large-scale farmer involved with Benson inns and coaching, (fn. 138) while Lower Berrick Farm was successively leased to the Ansells, Jacobs, and Coopers. (fn. 139) Seventeenth- and 18th-century prosperity was reflected in rebuilding of houses and farm buildings, (fn. 140) although some smallholders and cottagers remained. (fn. 141)

During the 1760s–80s both colleges converted some farms to leasehold, but still granted long tenancies for small rents and large entry fines. (fn. 142) Farming changed little, with wheat and barley still dominant and some sheep flocks of over 100 recorded into the 18th century. (fn. 143) Markets included Henley, (fn. 144) with whose malting industry some Berrick farmers had links. (fn. 145) Other produce was sold to buyers at Wallingford, Benson, Shillingford, North Stoke, and Milton. (fn. 146)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

A tithe commissioner commented in 1838 that while most lands at Berrick were in 'good cultivation there was 'no particular instance of High Farming', (fn. 147) and given the initial continuance of open-field agriculture the over-all pattern changed only gradually. The two largest farmers in the 1830s–50s (both predominantly tenants) were Thomas Weller of Roke Farm and Edward Belcher of Lower Berrick Farm, each with over 200 acres. Weller's holdings included Allnutt's farm in Berrick, let separately until not long before. Smaller tenant farmers c.1840 included Thomas Spyer (c.68 a.) at Malt House Farm, the Bonners (c.60 a.) at Ivyhouse Farm, and a few smallholders, while outside farmers included Harriet Parsons of Benson, Lincoln College's tenant at Parsons' Farm. Amalgamation continued, and by 1861 Weller and the Belchers farmed a combined total of 800 a. from Roke, Lower, and Ivyhouse Farms, employing 46 labourers. The parish's only other remaining farmer was a Lincoln College tenant with 18 a., the rest of the population comprising chiefly labourers' families and a few shepherds or craftsmen. (fn. 148)

Controversial attempts at inclosure in the 1820s–30s were opposed by Weller and some other Berrick farmers, despite a partisan assertion in 1837 that 'most of Berrick' was in favour. (fn. 149) Inclosure finally came in 1863, creating more compact farms and ending common grazing. Even so much of the former common remained grassland, and no new Berrick farms were created. (fn. 150) Successive members of the Weller and Belcher families continued to dominate Berrick's farming until the end of the century: in 1881 Sophia Weller farmed 300 a. from Roke and Benjamin Belcher 90 a. from Ivyhouse, while Jonathan Weller ran 270 a. from the combined Parsons', Allnutts' and Grace's Farms, held under Lincoln and Magdalen Colleges on conventional short-term leases. Jonathan drained some of the wetter land on his Lincoln holding, but faced difficulties during the agricultural depression, which the college blamed on his alleged poor farming and insufficient capital. His rent was reduced to 235. an acre, and following his premature death his widow continued into the 1890s. (fn. 151) Probably in response to the depression the parish's over-all proportion of arable (excluding fodder crops) fell from 52 per cent in 1866 to 47 per cent in 1889 and 49 per cent in 1902, when wheat covered 138 a., barley 67 a., oats 35 a., and beans or peas 47 acres. Cattle numbers rose from 31 to 64, although sheep (typically for the area) fell from 970 to 419, and pigs from 76 to 29. (fn. 152) Several smallholders remained, one of whom carted his produce to Chiswick (near London) every week, while portable steam power (hired from firms in Wallingford and Cowley) was in regular use on Berrick's larger farms by c.1900. (fn. 153)

The early 20th century saw several new tenancies, with Lower farm briefly run by bailiffs for the prominent Newington farmer John Deane. G.A. Weller continued as Magdalen's tenant in the 1940s, however, when he farmed 455 a. comprising Grace's, Allnutt's, and Ivyhouse farms. Lower farm (185 a.) was then run by W.F. Surman, and Parsons' farm (76 a.) by the Edwards family (tenants since 1901), who combined it with Home farm in Crowmarsh Gifford and bought the freehold in 1943. (fn. 154) Pasture accounted throughout that period for over half Berrick's farmland, supporting (c.1941) 248 cattle, 57 pigs, and 95 sheep; the latter (on Parsons' farm) were a recent reintroduction, sheep-farming having otherwise disappeared from Berrick by 1930. Wheat, oats, and barley remained the chief crops, with a few potatoes, mangolds, and turnips or swedes, while over 450 poultry were kept on the main farms and three smallholdings. All the farms were well run, and Lower Farm had a tractor, (fn. 155) although Lincoln Colleges land was suitable only for summer pasture. (fn. 156)

In 1960 there were still three farms over 100 a. and one over 500 a., alongside several smallholdings. Arable had increased to 65 per cent (with more barley grown than wheat), and there was some large-scale pig and poultry rearing. By 1988 arable was back down to 31 per cent, with pastoral farming marked by continued cattle rearing and by resurgent sheep-farming. (fn. 157) During the 1970S-80S, however, Berrick's farmland was almost entirely sold to outsiders and its farmhouses to private owners, leaving only Berrick Prior's Manor Farm still functioning (as a small sheep farm) in 1999. (fn. 158) Stonehaven Nurseries, a fruit and market gardening centre established in 1962, closed c.1991. (fn. 159)

TRADES, CRAFTS, AND RETAILING

Small-scale brewing was common in medieval Berrick, half a dozen tenants being fined in 1462–3 for breaching the assize of ale. (fn. 160) A medieval seal inscribed with the name of John le Tanner of Berrick was found in the late 19th century, (fn. 161) but generally traditional rural crafts were mentioned only sporadically, suggesting reliance on neighbouring places. (fn. 162) A weaver, cordwainer, carpenter, and blacksmith were briefly mentioned in the 1720s– 30s, (fn. 163) and the farmer Richard Wise (d. 1778) ran a shop selling groceries and chandlery. (fn. 164) Even so in 1811 only three families were supported by trades or crafts, compared with thirty by agriculture. (fn. 165) Small-scale malting may have begun c.1678 when a Henley maltster took up a Berrick Salome copyhold, (fn. 166) and by 1762 there was a malthouse at Lincoln Colleges Malt House Farm. In the early 19th century it was run by the prosperous maltster Thomas Weller (d. 1817), (fn. 167) but apparently ceased operating soon after.

Craftsmen in 1841 (some probably based in the Berrick part of Roke) included a thatcher, hurdlemaker, wheelwright, shoemaker, tinman, and blacksmith. (fn. 168) The Gale family's carpentry and wheelwrights' business at Cow Pool in Berrick continued until the First World War, (fn. 169) and a nearby smithy into the 1870s, the village relying thereafter on two Benson blacksmiths who visited with a portable forge. (fn. 170) Two small shops in 1851 included James Jacobs' grocery, which sold beer and continued in the 1880s, (fn. 171) while other beer shops or off-licences included the Plough and Harrow (now Plough Cottage) on Berrick street. (fn. 172) More unusual late 19th-century tradesmen included a 'canine merchant', a coal and corn dealer, bricklayers, a house decorator, a plumber, and a chimney sweep, while a few women worked as dressmakers, laundresses, or charwomen. A veterinary surgeon was mentioned in 1871, and an insurance agent in 1901. (fn. 173) By 1939 traditional crafts were apparently confined to Roke and Rokemarsh, and though Berrick inhabitants included a decorator, insurance agent, and the postmistress-cum-shopkeeper, employment thereafter became increasingly focused outside the village. (fn. 174)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

As an outlier within the Benson royal estate, (fn. 175) mid 10th-century Berrick was most likely inhabited by demesne workers or farm bailiffs. Subsequent reorganizations must, however, have profoundly altered its social character. The possible creation of an estate for three royal servants in 996 was followed by the transfer of Berrick's northern part to Canterbury cathedral in the early 11th century, and by the granting of the remainder to a minor local thegn whose nephew (Ordgar) retained it in 1066. The family almost certainly resided and may have founded the chapel, running a home farm partly with tied estate workers or servi, and leasing remaining land to tenant villani and bordarii. At the Norman Conquest Ordgar was one of only a few English landholders to retain his estate, with the powerful Norman baron Miles Crispin intruded as his overlord. Berrick's subsequent absorption into Miles's manor of Chalgrove left the village with a standard medieval community of small peasant farmers, but no resident lord. (fn. 176)

By the 1270s the village community comprised a mixture of free tenants and unfree villeins or cottagers. The villeins (then in the majority) attended Chalgrove's regular manor courts, paying cash fines for marriage, transfer of property, or bastardy, and performing occasional labour services on the lords' Chalgrove demesne farms. If required they were to serve as rent collector for Berrick and as reeve for Chalgrove. (fn. 177) Holdings were probably granted for two or more generations as later, with widows holding in their own right, (fn. 178) and although some villeins apparently farmed little above subsistence level, early 14th-century tax returns imply considerable variance in individual prosperity. A few shared in former demesne land ready-stocked by the lord, suggesting communal cooperation and a marked social hierarchy. The five free tenants recorded in 1279 had slightly larger holdings, and generally owed only cash rents and attendance at court. Possibly they included some former villeins granted free tenure by the lord, since several occupied former villein or demesne land. (fn. 179) Lessees of the reputed 'Berrick manor' freehold are not recorded before the early 15th century, but may already have been a significant local presence. (fn. 180)

Distinctions probably blurred in the later Middle Ages, as customary tenants accumulated larger holdings and manorial authority weakened. (fn. 181) Orders to repair superfluous buildings on amalgamated farms often went unheeded, (fn. 182) and in 1469 a holding was forfeited because its tenant was living in Newington without the lord's licence. (fn. 183) The late 14th and early 15th centuries also saw increased immigration, with long-established tenants such as the Brictweys, Kemps, and Runcivals replaced by families such as the Pipers, Cotterells, Wises, and Mores, (fn. 184) some of which remained for several centuries. (fn. 185) Berrick lacked any higher-status inhabitants, although the non-resident freeholder Sir John Butler (d. 1477) married the widow of one of Chalgroves lords. (fn. 186)

Close relations with Chalgrove were ensured through ecclesiastical as well as manorial ties: Berrick Salome chapel was served from Chalgrove, and its parishioners were possibly buried there. (fn. 187) In the early 14th century the two places were generally taxed together, and Berrick possibly also looked to Chalgrove (as well as to Warborough, Benson, or Dorchester) for goods and services. (fn. 188) Operation of the shared open fields required regular contact with Benson and Ewelme tenants or their lords, while close ties existed with Roke (which remained partly in common lordship with Berrick), (fn. 189) and presumably with Berrick Prior, the two Berricks being occasionally still called a single vill. (fn. 190) Some community cohesion was presumably provided by Berrick Salome chapel which, despite its dependency, had its own chapel-wardens by 1424, and saw considerable local investment. (fn. 191) Recorded conflict was generally confined to minor agricultural disputes, (fn. 192) although a Berrick tenant was murdered by five Dorchester men in Chalgrove c.1285. (fn. 193)

1500–1800

Berrick remained dominated by emerging yeoman families until the 18th century, most of them farming a mixture of copyhold and freehold land. Changes of lordship had little impact: copyholds were still granted at the Chalgrove manor courts, which appointed tenants to oversee field regulation and other affairs, while Berrick's vestry became increasingly important for parish government, particularly poor relief. Late medieval families such as the Wises, Cotterells, Mores, and Viccarys remained prominent into the 17th century or later, alongside relative newcomers such as the Spindlers and Barretts, of whom the latter were still resident in the 1740s. (fn. 194)

The most notable families included the Smiths, Hambledens, and Barretts, successive holders of the 'Berrick manor' freehold. (fn. 195) John Smith (d. 1534), the wealthiest taxpayer in 1524, had property in several parishes and endowed a chaplain for Berrick chapel, besides acting as Magdalen Colleges bailiff. (fn. 196) William Hambleden (d. 1550) owned property in Berrick Prior, Warborough, Watlington, and possibly Wallingford (where he asked to be buried), and left money for Wallingford bridge and for Berrick's chapel and roads. (fn. 197) His descendant John Hambleden (d. 1672), Berrick's wealthiest recorded farmer, occupied the villages largest house (almost certainly Lower Berrick Farm), which was taxed on six hearths. At his death it included a hall, two parlours (one decorated with wall hangings), and at least six chambers, while his poultry included 11 peacocks and peahens and a 'flight of pigeons'. (fn. 198) Hambleden's sister married into the Barrett family, (fn. 199) already well established in Benson, Roke, Berrick, and Stadhampton, and whose members sometimes called themselves gentlemen'. (fn. 200) Most other leading yeomen were not quite so wealthy, though several left substantial farm stock and, like their contemporaries elsewhere, lived in increasing domestic comfort, occasional luxuries including glassware, books, and clocks. (fn. 201) Together they formed a tight-knit group which dominated village affairs, while maintaining extensive links elsewhere. Many daughters married outside the parish, while places mentioned in wills included Wallingford, Benson, Watlington, Henley, Cholsey, Goring, and London, alongside villages nearby and in Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, and west Oxfordshire. (fn. 202)

Such families employed local servants and farm workers, (fn. 203) not all of whom were especially impoverished. A landless shepherd in 1641 occupied a sparsely furnished two-room house, but one labourer in 1714 had a best and two other chambers, while another had 10 a. of land and made elaborate family bequests. (fn. 204) Most, however, were probably much poorer. Cottagers with under ¼ yardland (5–6 a.) lacked even common rights for cows, (fn. 205) and in 1759 the vicar commented that offertory donations in Berrick were so small that he passed them straight to poor communicants and the sick. (fn. 206) Village conflict seems to have been mostly confined to standard disputes over tithes, (fn. 207) commons, rights of way, petty theft, and bastardy cases (usually involving women outside the parish), (fn. 208) although the village suffered disruption during the Civil War, (fn. 209) and in the early 18th century groups of local people were twice accused of riotously attacking neighbours' houses. (fn. 210) Social life is poorly recorded, but by the 1750s probably largely focused on the Chequers pub, technically in Berrick Prior. (fn. 211) An alehouse called the Compasses (formerly the Lamb) was mentioned in 1780. (fn. 212)

Since 1800

By the early 19th century some larger farms were emerging, and though families such as the Allnutts, Ansells, Coopers, Jacobs, Spyers, and Tanners remained prominent in village society, the Wellers and Belchers (of Roke and Lower Farms) became increasingly the largest employers of labour, (fn. 213) apparently using their influence to encourage church attendance. (fn. 214) Other better-off inhabitants included four women from local farming families living off rents or investments, who like the chief farmers generally had a live-in domestic servant. Most local girls apparently entered service elsewhere, however, since only one servant in 1851 was Berrick-born. The largest proportion of the working population (nearly 60 per cent in 1851) comprised agricultural labourers with little or no land, (fn. 215) widespread poverty being reflected in occasional thefts of crops or wood. (fn. 216) In 1830 Berrick was reportedly also caught up in local Swing Riots, although those involved were apparently outsiders. (fn. 217) Around half the population in 1851 remained native to Berrick Salome or Roke, with 74 per cent born in Berrick or contiguous parishes. (fn. 218) The closest social ties were with Berrick Prior, Roke or Rokemarsh, and Benson: interaction with Chalgrove was said to be minimal, despite continued ecclesiastical connections. (fn. 219)

Daily social life still focused on the Chequers and other pubs, (fn. 220) while a 3½-a. recreation ground was created at inclosure in 1863, and village cricket and (to a lesser extent) football were well established by the 1880s. Other communal activities c.1900 included the Roke band (established in 1882), bell-ringing, and watching local gatherings of the South Oxfordshire Hunt, (fn. 221) while in 1909 there was a popular Mothers' Union and Guild of Church Workers, balanced by Nonconformist social events at Roke. (fn. 222) Berrick Feast, on the Monday before 29 September, was held near the Chequers just over the parish boundary, and was apparently combined with Berrick Priors; it reportedly included 'the throwing about and eating of crab apples', and continued into the 1920s. (fn. 223) Coal and clothing clubs existed by the 1880s, (fn. 224) and a nursing association (shared with Benson and Ewelme) was mentioned in the 1920s. (fn. 225) Occasional misdemeanours were of the usual trivial kind, although c.1900 two villagers were subjected to 'rough musicking' by their neighbours. (fn. 226) The limited means of even the leading local farmers was reflected in fundraising for church restoration in 1889–90, which relied overwhelmingly on outside aid. (fn. 227)

Following the First World War falling agricultural employment began to alter Berrick's character, and by the 1930s semi-derelict cottages were attracting outsiders (including some from London) seeking a weekend retreat. (fn. 228) Local farms employed only 11 workers c.1941, (fn. 229) and change accelerated after the Second World War, bringing in commuters and professionals particularly from the 1970S-80S as remaining farmhouses and cottages were sold. By 1999 scarcely any farming-related families remained, although the extended parish (encompassing Roke, Rokemarsh, and Berrick Prior) developed a strong community identity. A village hall (transported from Green College in Oxford) was erected c.1980 through community effort, and Roke band continued, while annual events included rounders and cricket matches, the church fete (alternating with a Berrick and Roke village show), and a popular Christmas Eve church service. Activities partly reflected the presence of numerous families with children, contrasting with the ageing population reported in the late 1940s. (fn. 230)

EDUCATION, CHARITIES, AND POOR RELIEF

Mary White (by will dated 1729) left a 305. annual rent charge for teaching poor children to read, with a similar sum allocated to Berrick Prior. In 1823 the payment (less 35. land tax) went to a Berrick Salome schoolmistress who taught two children free, (fn. 231) and another schoolmistress was resident in 1851. (fn. 232) Even so the village was consistently said to have no school of its own, (fn. 233) and by the later 19th century most children attended Benson schools or (in the 1860s-70s) an Anglican infant school at Roke. (fn. 234) From 1884 the White bequest was accordingly diverted to school prizes. (fn. 235) A private nursery school was briefly accommodated in Berrick village hall in the late 20th century. (fn. 236)

Occasional one-off bequests to the poor were made from the 16th century, the most substantial (£10) by a vicar of Chalgrove in 1609. (fn. 237) Berrick also shared in endowed charities established by the Chalgrove vicar John Wall (d. 1666) and by Alice Markham (d. 1679), widow of Wall's successor, receiving respectively two fifths and one third of the income. In 1759 the charities were 'misapplied', but in 1823 yielded £4 14s. 11d. for Berrick; the sum was distributed in cash on St Thomas's Day (21 December) along with 6 bu. wheat, a gift whose origins were unknown. (fn. 238) An additional £5 bread charity (distributed from the chapel gallery) was established by the London coachmaker Thomas Smith (d. 1812), one of a local family who retained property in the parish. (fn. 239) As elsewhere, most poor-relief costs were by then met from parish rates. Expenditure of c.£35 in 1785 (including £2 10s. on pauper accommodation) rose to £127 by 1803 and to £268 in 1813, when 11 people received permanent and 36 people occasional relief. Later expenditure ranged from c.£130 to £231, the slightly below-average per capita costs presumably reflecting local farm employment. (fn. 240) Responsibility passed in 1835 to Wallingford Poor Law Union, (fn. 241) although the parish still appointed overseers, a poor-law guardian, and (occasionally) an assistant overseer. (fn. 242) Allotment gardens for the 'labouring poor' were laid out at Berrick Littleworth at inclosure in 1863. (fn. 243)

In 1977 the Mary White educational charity was merged with the three eleemosynary charities to create the Berrick Salome Relief in Need Charity, which in 2012–13 distributed over £1,400. (fn. 244) The Berrick Salome Quarry Charity, benefiting a variety of local organizations, was established in 1990, administering income from a small former gravel quarry allocated to the parish for road repair at inclosure. (fn. 245)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

CHAPEL ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

Berrick chapel existed by the late 11th or early 12th century, having probably been founded fairly recently by a lord of the four-hide estate recorded in Domesday Book. (fn. 246) A chaplain was mentioned in the early 13th century, and the building itself in 1258. (fn. 247) At first it was possibly subject to Benson church, but by the 13th century, following Berrick's absorption into Chalgrove manor, it had become a dependency of Chalgrove, whose incumbents served it directly or through hired priests. (fn. 248) In 2015 the two still formed a joint benefice in the gift of Christ Church, Oxford. (fn. 249) The chapel's dedication to St Helen is not recorded before the 19th century, (fn. 250) and was presumably copied from that of Benson. In 1554 the dedication was to St Peter. (fn. 251)

Berrick's tithes passed first to the rector of Chalgrove and in 1319, with Chalgrove's rectory estate, to Thame abbey. Inhabitants' offerings were apportioned to the newly-appointed vicar of Chalgrove, and from 1392 or 1471 his successors received the Berrick tithes as well, (fn. 252) explaining their later title of vicar of Chalgrove and rector of Berrick. (fn. 253) An annual 'Berrick pension paid by the vicar to Thame abbey (and after the Dissolution to Christ Church) was probably in recompense for the tithes, and in the 1520s–40s totalled 36s.–40s. In 1837 the vicar owed £10 19s. as an accumulated sum, (fn. 254) and the pension remained due in the 1890s after Christ Church refused to waive it. (fn. 255) Berrick's tithes themselves were collected in cash by the 1830s, and were formally commuted to a £200 rent charge in 1839. (fn. 256)

Small parcels of glebe in Berrick belonged to Chalgrove rectory by the 1270s, (fn. 257) and like the tithes were transferred to the vicar probably in the later Middle Ages. In 1787 they were reckoned at 12 a., and in 1839 at 6 a. including a garden and two closes. (fn. 258) One of the latter, near Lower Berrick Farm, contained a barn, succeeding a 'parsonage house' (possibly only farm buildings) mentioned 1579. (fn. 259) Some of that glebe may have formed part of Berrick chapel's original endowment, although in the 16th century some open-field land was thought to represent more recent gifts by an unnamed lord. (fn. 260) The vicar retained the Berrick glebe (7½ a. after inclosure) in 1939. (fn. 261)

The chapel probably had baptismal rights from its foundation, and from 1609 (when Berrick's registers begin) baptisms, marriages, and burials were systematically recorded. (fn. 262) Whether burial at Berrick was yet fully established is unclear, however: no surviving 16th- or 17th-century wills requested burial there, several testators specifying Chalgrove and (occasionally) other local churches, (fn. 263) while some at least of the burials noted in the earliest Berrick registers were apparently actually at Chalgrove. (fn. 264) A bier dated 1637 nevertheless survives in Berrick chapel, (fn. 265) and tomb chests from the late 17th or early 18th century, (fn. 266) while in 1717 a parishioner expressly requested burial at Berrick. (fn. 267) By 1424 the chapel also had its own wardens, (fn. 268) and although its subservient status was never in doubt it was occasionally called a church. (fn. 269)

A small estate for the chapel's upkeep (comprising a cottage and 6¾ a. in the open fields) was vested in feoffees in 1618, having presumably been given by one or more benefactors at an unknown date. Income was paid to Berrick's churchwardens, its application overseen by the Berrick vestry meeting and the vicar of Chalgrove. (fn. 270) In 1884 the estate (c.10 a. after inclosure) was vested in the Official Trustee of Charitable Lands, (fn. 271) and in the 1970s part of the accumulated income (£143 in 1975) was put towards repairs, building inspections, and PCC costs. (fn. 272) The cottage had gone by 1823, leaving only a garden. (fn. 273)

PASTORAL CARE AND RELIGIOUS LIFE

Little is known of how Berrick was served during the Middle Ages. Ralph the chaplain of Berrick witnessed a Chalgrove land grant c.1210–20, (fn. 274) and some other clerks or chaplains mentioned in local transactions may have assisted, amongst them (c.1375) the future vicar of Chalgrove John Bonere. (fn. 275) From 1319 Chalgrove's vicars were legally required to provide a chaplain and probably books for Berrick, their later receipt of Berrick's tithes perhaps reinforcing the obligation. (fn. 276) Medieval remodelling of the chapel (including addition of a timber-framed tower c.1429) suggests lay and probably communal investment, (fn. 277) and by the Reformation its possessions (besides the chapel estate) included a silver chalice and an acre given to maintain a light. (fn. 278) A curate mentioned in 1526, though not necessarily resident, received a stipend of 535. 4d., (fn. 279) and in 1534 the leading Berrick yeoman John Smith left £5 6s. 8d. for a priest to celebrate mass in Berrick three times a week for a year (including Sundays and holidays), and once a week at Chalgrove. (fn. 280)

The Reformation seems (as at Chalgrove) to have been outwardly accepted, (fn. 281) and in the later 16th century a few inhabitants made modest bequests to the chapel. (fn. 282) Vicars and other clergy occasionally witnessed Berrick wills, those named including Henry Parsons (1580) and Arthur Laurence (1584), probably both curates, and the Chalgrove vicar William Huske (1558). (fn. 283) A curate serving Berrick and Benson in 1586 was reportedly 'of mean ability', (fn. 284) but a fellow of Jesus College, Oxford, was licensed as curate in 1633, (fn. 285) and in 1651, during the Interregnum, James Cowes of Christ Church was briefly appointed 'minister' of Berrick. (fn. 286) Substantial refitting of the chapel during the 17th century points to large-scale investment by parishioners, (fn. 287) and following the Restoration the vicar Francis Markham's widow Alice (d. 1679) donated a silver paten, and remembered Berrick's poor in her will. A surviving silver chalice is hallmarked 1657. (fn. 288)

Despite such developments small-scale Protestant Dissent emerged from the 1660s, perhaps encouraged by the absence of resident clergy, the parish's scattered settlement, and the church's relative remoteness. (fn. 289) Eight Nonconformists (compared with 80 Anglicans) were reported in 1676, (fn. 290) and in 1682 the vicar listed a Quaker, an Independent, and a Baptist Sabbatarian. The Quaker was probably associated with the Warborough meeting, which enjoyed particular support at Roke, while the Independent (John Low), also of Roke, was associated with another Warborough group. The Sabbatarian (the farmer Joseph Wise) was a member of Edward Stennett's conventicle in Wallingford, and in 1700 his house at Berrick was licensed for worship. (fn. 291) Adherents from neighbouring parishes still met there in the 1730s, (fn. 292) but thereafter no Nonconformity was reported in the chapelry before the 19th century, despite establishment of a Baptist chapel in the Benson part of Roke in 1739. (fn. 293)

By 1738 the Anglican chapel had only an afternoon Sunday service conducted by the vicar's curate, who lived in Chalgrove. A similar pattern continued into the early 19th century, with services (incorporating a sermon) held in the afternoon or morning, and communion administered four times a year as at Chalgrove. Up to 40 Berrick communicants were noted in 1802, but only 8 in 1811 and 10–20 in 1817, when a few parishioners were habitually absent from 'ignorance', 'want of religion', or unknown motives. Catechizing took place at Berrick in the 1730s-50s, but sometimes no children attended and by 1802 it had ceased. (fn. 294) Conflict erupted in the 1750s following a vicar's intervention over parish charities, although relations seem to have recovered. (fn. 295)

During the 1830s–50s Chalgrove's long-serving vicar Robert French Laurence (1832–85) introduced monthly communion at Berrick, but proved unable to sustain a second Sunday service. (fn. 296) Thereafter he campaigned for several decades for Berrick to be made a separate parish, to incorporate Berrick Prior (whose inhabitants habitually attended Berrick chapel), Roke, and Rokemarsh. Christ Church refused to cooperate, (fn. 297) and although a resident curate for Roke and Berrick Salome was briefly appointed c.1861–4, funded jointly by the vicar (£20), the incumbent of Benson (£20), and the Diocesan Spiritual Help Society (£40), (fn. 298) earlier arrangements largely continued. In 1869 attendance at Berrick's Sunday service averaged 40–60 out of a population of c.145, a higher proportion than at Chalgrove 'as the [Berrick] farmers set a better example and are more attached to the Church'. (fn. 299) A small west-gallery band (including a fiddle-player) accompanied services, (fn. 300) and regular communicants, including outsiders presumably from Berrick Prior, numbered 5–9. (fn. 301) Even so Laurence feared that lack of a resident minister encouraged Dissent, (fn. 302) and in 1878 surmised that perhaps a quarter of inhabitants (probably chiefly in Roke) attended nearby Nonconformist chapels. (fn. 303) In 1855 Berrick was one of several parishes whose candidates for confirmation were considered ill-prepared by the bishop. (fn. 304)

A curate briefly drafted in after Laurence's departure won the inhabitants' warm approbation for instating two Berrick services, but under George Blamire Brown (vicar 1885–1902) the earlier pattern resumed. (fn. 305) Brown restored the chapel (in 'tolerable' repair under Laurence), (fn. 306) and in 1909 the Berrick Mothers' Union, Guild of Church Workers, and Sunday school (run by a parishioner) each had 20-odd members, with 32 communicants out of a population of 87. A surpliced choir established before 1890 (when the chapel acquired a harmonium) continued until the First World War. (fn. 307) Otherwise there was little change until 1938–49, when the rector of Newington served as priest-in-charge of both Berrick and Chalgrove. (fn. 308) In 2013 (when Berrick was again served from Chalgrove) there was a weekly Sunday service, a monthly family service, regular communion, and a popular candlelit Christmas Eve service, while varied fundraising events helped maintain the church as a community focus even for non-churchgoers. (fn. 309) Ecclesiastical boundaries were adjusted in 1985, bringing them in line with the civil boundaries. (fn. 310)

CHURCH ARCHITECTURE

Berrick's small medieval chapel, substantially altered in the 17th century and again in 1890, is notable for its timber-framed west tower of c.1429, a feature unique within Oxfordshire, and uncommon nationally (fn. 311) The rest of the building - nave and chancel (with no chancel arch), south porch and south transept chapel, and added north vestry - is predominantly rubble-built and rendered, with some 17th-century brick mullions, and restored timber-framing in the porch. Decorative barge-boarding was added in 1890, when the tower was clad in striking red and grey bands of fish-scale tiles and wooden shingles. (fn. 312)

The earliest dateable feature is the plain round-headed south doorway, probably late 11th- or early 12th-century. A small Norman-style window to its east was constructed in 1890 from fragments found in the north and south door jambs during restoration. (fn. 313) The 11th- or 12th-century font, with its interlaced beaded circles, is of high status and may have been imported from elsewhere (possibly Chalgrove), although it was certainly in the church by 1822. (fn. 314) Thirteenth-century remodelling is reflected in the Early English north doorway and in a lancet window (possibly reset) in the transept's east wall: the transept itself was probably added around the same time, presumably as a side- or chantry chapel, and retains a timber roof of probably 15th-century date. The chancel was rebuilt in the 14th century, equipped with piscina and aumbry and lit by trefoiled lancets and a tall east window with intersecting tracery. (fn. 315) The structurally independent tower has been tree-ring dated to 1428–9, probably replacing a bellcote, and in 1553 housed two bells; (fn. 316) possibly a timber-framed structure was all the community could afford. Inlaid medieval floor tiles, a fragment of stained glass, and 'bright-coloured' scroll-pattern wall paintings were discovered in 1890, when the glass and tiles were reset. (fn. 317)

Berrick Salome chapel from the south-west, showing the tower's distinctive cladding added in 1890.

The chapel was substantially remodelled during the 17th century, beginning with construction of a fine oak roof to the nave in 1615 and associated rebuilding of the upper walls. Brick-mullioned windows in the nave and transept may be of similar date. Box pews were provided in 1636, a parish chest in 1638, and a timber west gallery in 1676, lit by surviving dormers, while further 17th-century refurbishments included wooden altar rails and a new communion table. (fn. 318) The bells were expanded to a ring of five, two of them (by Henry Knight) dated 1621, and three others 1692. (fn. 319) Thereafter only running repairs were recorded, the fabric becoming increasingly dilapidated during the 18th and 19th centuries. Problems in 1759 included cracks in the chancel walls and wear to roofs, buttressing, and paving, (fn. 320) while churchwardens' neglect of the churchyard mounds prompted a threat of excommunication in 1792. (fn. 321) Pews and flooring were repaired in 1840, (fn. 322) and a sixth bell (funded by subscription) was added in 1836. (fn. 323)

By the 1880s the walls were unstable, tiling dilapidated, and the interior disfigured by mildew. Restoration by Alfred Mardon Mowbray of Oxford followed in 1890 through the efforts of the vicar George Blamire Brown, the £699 cost met chiefly from external subscriptions, a mortgage on the chapel estate, and a loan from Queen Anne's Bounty. Walls, windows, and roofs were repaired, the nave's Jacobean roof having been re-discovered behind arched plaster ceilings. The gallery was moved a few feet westwards and placed on carved stone corbels with biblical inscriptions; a new vestry was added on the north, entered through the nave's reopened north door; and the east window was replaced by a near-copy of its predecessor. Externally the tower was transformed by its tile and shingle cladding (replacing dilapidated weather-boarding), while decorated barge-boards were added to the dormers and reconstructed timber-framed porch. Internally a new oak altar, choir stalls, lectern, and pulpit were installed (the chancel and altar being both slightly raised), the box pews were lowered and rearranged, and the font reset. (fn. 324) Mowbray's external application of 'the trappings of fashionable late 19th-century domestic architecture' has attracted harsh modern criticism, but contemporary reactions were more favourable, and much of the building's historic fabric was preserved. (fn. 325) A new wrought-iron bell frame was installed in 1908 and electric lighting in 1938, most later work being purely restorative. The pulpit (suffering from dry rot) and choir stalls were removed in 1982, and the harmonium replaced by an electric organ in 2003. (fn. 326)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

MANOR COURTS AND OFFICERS

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century Berrick's inhabitants attended Chalgrove's manor courts, held from the 16th century by Magdalen and Lincoln Colleges, Oxford. (fn. 327) The courts granted copyholds, collected manorial fines, laid down manorial custom, and heard jurors' presentments regarding over-grazing, blocked lanes and ditches, or similar disputes. (fn. 328) An ale taster (presenting brewing offences) was mentioned in 1462–3. (fn. 329) Inhabitants were also represented at the honor of Wallingford's annual view of frankpledge at Chalgrove, which by the 16th century appointed a constable and a tithingman for Berrick, and sometimes also ruled over grazing or blocked ditches. (fn. 330) In the early 19th century it also appointed a hayward. (fn. 331) Magdalen's courts dealt with Berrick business until inclosure in 1863, and continued until 1891, Lincoln's having apparently lapsed slightly earlier. (fn. 332) The annual views ended in 1847. (fn. 333)

PARISH GOVERNMENT AND OFFICERS

Berrick had two chapel- or churchwardens (procuratores) by 1424, when a parishioner granted them a toft on Berrick street. (fn. 334) By the 1460s they held an acre in the open fields for 5d. quitrent, (fn. 335) and by the 17th century they administered income from the 6¾a. church estate, given at an unknown date. (fn. 336) Overseers of the poor were appointed probably from the 16th century and certainly by 1679, (fn. 337) and in the late 18th century a field keeper (with counterparts in Benson and Ewelme) oversaw open-field intercommoning after harvest. (fn. 338) All were elected presumably by the Berrick vestry mentioned from 1618, (fn. 339) which may have had medieval antecedents. As elsewhere, offices were held by leading farmers, sometimes for several years. (fn. 340) At inclosure the churchwardens received 9¾ a. for the church estate and their earlier acre, and with the overseers were given oversight of the new recreation ground and labourers' allotments. The surveyor of highways received 2 a. for use as a gravel quarry. (fn. 341)

Vestry meetings in the 1880s–90s were held usually in the chapel or Chequers inn around Easter, attended by the vicar and a few prominent farmers or tradesmen who elected the churchwardens, allotment wardens, and a way warden, nominated overseers, and audited accounts. The churchwardens (with the vicar) also administered the parochial charities, while a salaried assistant overseer was appointed in 1891 following a controversial parish vote. (fn. 342) The vestry's remaining civil responsibilities passed under the 1894 Local Government Act to a new parish meeting which, following the parish's expansion in 1992, continued as a parish council of five with a parish clerk. (fn. 343) Two churchwardens were still elected, although in 2013–14 one post was vacant. (fn. 344) The parish was transferred in 1894 from Wallingford Poor Taw Union and Rural Sanitary District to Crowmarsh Rural District, and in 1932 to Bullingdon Rural District, passing in 1974 to South Oxfordshire District. (fn. 345)