Pages 254-281

A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

In this section

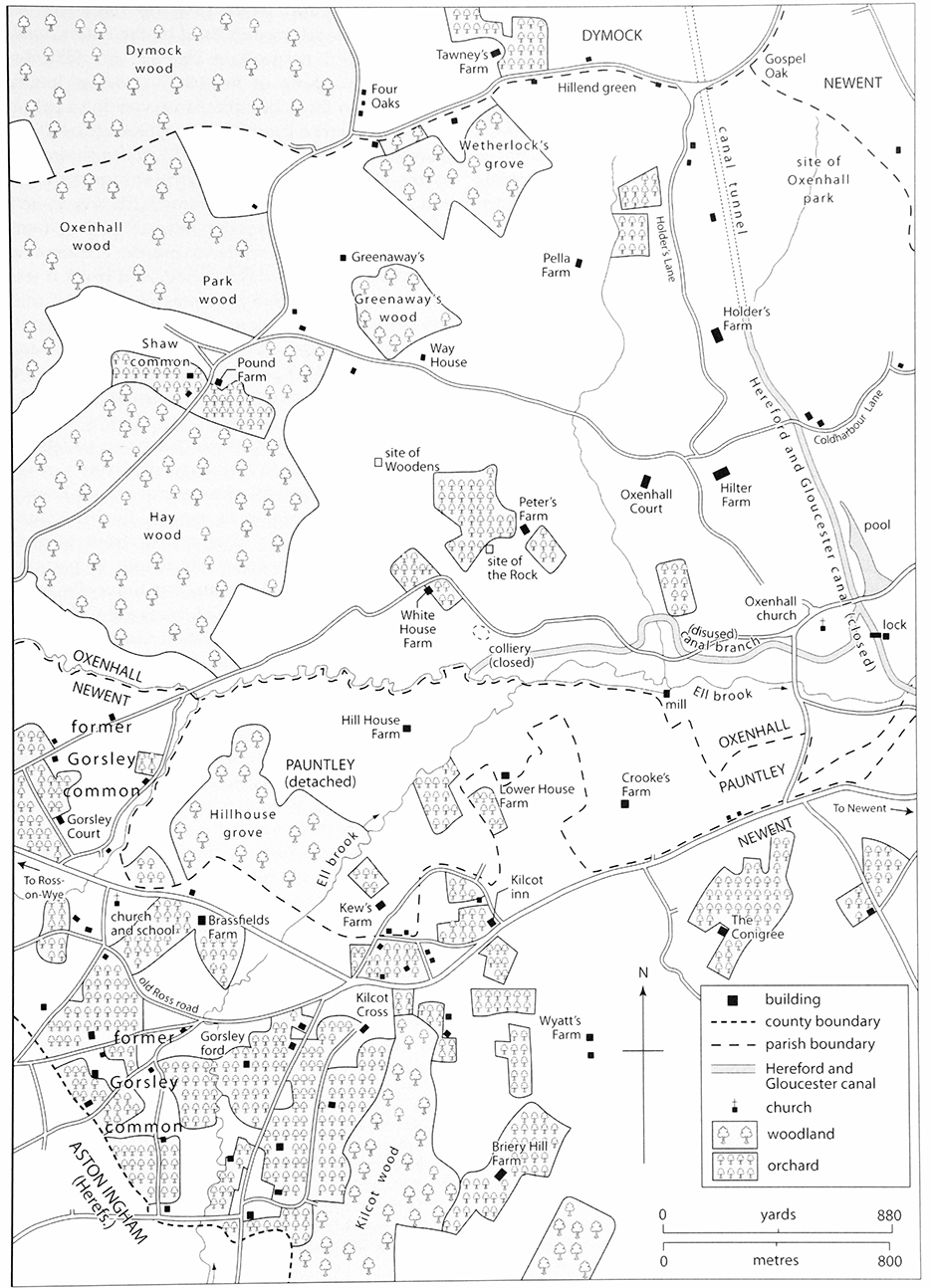

OXENHALL

OXENHALL, a small parish of scattered farmsteads, lies on the north-west boundary of Gloucestershire, its south side adjoining Newent town. The ancient parish covered 1,909 a. (fn. 1) (772 ha). Part of its west boundary and a longer part of its south boundary followed a stream which skirted the wood called Hay wood and joined Ell brook at about the mid point of the south boundary. (fn. 2) From that confluence the boundary followed the leat of Crooke's Mill, diverged southwards to take in a tract of land formerly known as the Hides, and rejoined Ell brook near Newent town at a bridge called Ell bridge. From near the bridge the east boundary followed a lane leading from Newent towards Botloe's green and then a track that joined the Newent–Dymock road near a place called Three Ashes. Leaving that road, it ran north-westwards across an area where in the early Middle Ages the lords of the manor formed a park incorporating land in both Oxenhall and Newent manors. (fn. 3) At Gospel Oak, named from a tree that stood there until 1893, (fn. 4) the boundary turned westwards to follow a lane along a ridge in the area known as Hillend and then a track running through woodland towards Kempley.

In 1883 Oxenhall parish was enlarged to include a detached part of Pauntley parish comprising 341 a. (138 ha) (fn. 5) between the Ell brook and its tributary and the Newent hamlets of Kilcot and Gorsley to the south. (fn. 6) This account includes the history of that part of Pauntley.

LANDSCAPE

Oxenhall parish (as enlarged in 1883) occupies rolling countryside rising generally to around 60–70 m but forming a more pronounced ridge, reaching almost 100 m, at Hillend in its north-east corner. The northwestern part of the parish is formed of the Old Red Sandstone and the south-eastern of the newer Triassic sandstone, which is visible in the sides of some of the lanes. Between the two formations occur thin coal seams, which were worked with no great success in the late 18th and the 19th century. (fn. 7) The soil is mainly a sandy loam of the type known as 'the ryelands' from the principal cereal crop once raised on it, but there are also areas of heavy clay. (fn. 8) The drainage system centres on the Ell brook into which fall some minor streams rising in the north of the parish. Field names suggest that the stream flowing down the centre of the parish and parting the lands of the farms called Oxenhall Court and Peter's Farm was once called Ash brook and that another further east, forming a valley that was used in the late 18th century as the course of the Hereford and Gloucester canal, was called Hub (or Up) brook. (fn. 9) On the latter stream a long pond, just above the road leading from Oxenhall church to the Newent–Dymock road, is a remnant of a system of ponds and watercourses that once powered Ellbridge (or Elmbridge) iron furnace, in the southeast corner of the parish. (fn. 10) Beside the Ell brook to the south of the parish church Gloucester corporation built a waterworks in 1896, pumping water from a borehole to a reservoir at Madam's wood in Newent parish, near Upleadon. Under the agreement for the purchase of the site from the Oxenhall manor estate the main tenant farms were provided with a free supply. (fn. 11)

Map 12. Oxenhall, Kilcot, and part of Gorsley, 1882

Over a quarter of the ancient parish comprises woodland, which was predominantly oak before the introduction of conifer plantations by the Forestry Commission in the mid 20th century. The western side of the parish is part of an extensive tract of woodland that straddles the county boundary. Within Oxenhall the main components were Hay wood in the south, covering 194 a. in 1775, and Brandhill, Oxenhall, and Park woods further north, together covering 176 a. in 1775. (fn. 12) In 1615 the bulk of Brandhill wood and a part of Hay wood near the parish boundary were on lease from the lord of the manor to individual tenants, (fn. 13) and further leases which included permission to fell the timber and convert the land to farmland were granted in the 1650s, mainly to a branch of the Hill family. By 1659 Park wood (50 a.) was on lease to Richard Messenger, (fn. 14) from whom it took its later name of Messenger's park. After 1659 the bulk of the woodland was retained in hand by the Foleys, lords of the manor, to produce charcoal for Ellbridge furnace, (fn. 15) but parts of Brandhill remained under cultivation in the hands of tenants, creating a belt of closes extending diagonally through the centre of the woodland (on the line taken in the mid 20th century by the M50 motorway). (fn. 16) An area at the north-east end of those closes, called in 1615 Little wood (fn. 17) and later Shaw common, was the only part of the woods where tenants were permitted to exercise commoning rights in the post-medieval period. As a result it was encroached and settled by cottagers from the mid 17th century. In 1775 24 a. remained common land, but by the mid 19th century most of that had been absorbed by further encroachment. (fn. 18)

Smaller woods, outliers of the main tract, included Cumming's grove (later Betty Daw's wood), Colonel's grove, and Wetherlock's grove, which lay together near the north boundary, and Rayer's grove, Coather's wood, and Wayhouse grove (later known collectively as Greenaway's wood), further south. Most of those woods were named from tenants who had held them under the manor as parts of copyhold and leasehold farms, but Colonel's grove was probably named from Col. Maynard Colchester (d. 1715) who owned it as part of the Oxenhall rectory estate. (fn. 19) In the detached part of Pauntley Hillhouse grove, covering 53 a. in 1775, (fn. 20) belonged to the lords of Newent and was kept in hand by the Foleys after they acquired that manor in 1659. (fn. 21) In the mid 20th century it was felled except for a small clump of trees and the land turned over to agriculture. (fn. 22)

Park wood in the main tract of woodland was called the new park in 1659, (fn. 23) evidently to distinguish it from a park enclosed by the lords of Oxenhall in the north-east of the parish. That park straddled the boundary with Newent and in the mid 13th century William of Evreux, lord of Oxenhall, gave Cormeilles abbey, lord of Newent, 4 a. of land to compensate for 2½ a. of the abbey's land enclosed within it. (fn. 24) In 1335, when it was grazed by the lord's deer, it was described as small (fn. 25) and in 1435 it was extended at 40 a., (fn. 26) but later evidence shows it was larger, incorporating a substantial tract extending as far as the Newent– Dymock road. It was leased in two halves by 1527, (fn. 27) and in 1659 six tenants held portions totalling over 150 a. (fn. 28) By the late 18th century it comprised arable and pasture closes indistinguishable from other farmland in the parish. (fn. 29) Further south on the same side of the parish, a small farm called Marshall's was converted as a golf course at the end of the 20th century, and a field near by, adjoining the lane from Oxenhall church to the Newent–Dymock road, was used by the Newent cricket club.

COMMUNICATIONS

Roads

Of the roads crossing the parish only that on the east side, leading from Newent town through Dymock to Ledbury, was used by other than very local traffic. It was a turnpike from 1769 until 1874. (fn. 30) The southern part, running past Lambsbarn, was apparently improved substantially by the trust c.1832. (fn. 31) Ell bridge, on the Ell brook where the road enters the parish, was repaired jointly by Oxenhall and Newent parishes. (fn. 32) It and another bridge further upstream, evidently at the crossing known as Ellford (or Ollifordes) south of Oxenhall church, (fn. 33) were both recorded in 1282 as landmarks on what was then the northern boundary of the Forest of Dean. (fn. 34) Various lanes running westwards from the Newent–Dymock road were used mainly for access to the parish's scattered farmsteads, though they also continued through the wooded area into adjoining parishes. A continuation of Furnace Lane, running from the site of the Ellbridge ironworks northwards to Winter's Farm, (fn. 35) is among minor lanes to be abandoned in the late 18th or early 19th century, most becoming disused with the disappearance of the farmsteads they served. The M50 motorway, opened in 1960 between the M5 and Ross-on-Wye (Herefs.), (fn. 36) crosses the north-west part of Oxenhall, but, screened by woodland and with no direct access from the parish, has had little impact on its landscape or settlement pattern.

Canal and Railway

The Hereford and Gloucester canal, begun in 1793 and opened between Gloucester and Ledbury in 1798, traversed the parish, with a tunnel, 2 km long, taking it under the high land at Hillend. A branch was constructed running west from the main line near Oxenhall church to serve small collieries near Hill House Farm in the detached part of Pauntley, but the lack of success of those workings led to the early abandonment of the branch. (fn. 37) Some time before 1812 a horse tramroad was laid through the west part of the parish across Shaw common and towards Gorsley common, probably following the lane through Hay wood. (fn. 38) It was probably built specifically to carry materials from quarries in the Linton (Herefs.) part of Gorsley for the building of the canal and its tunnel, and no later record of it has been found. The canal was closed and replaced in 1885 by the Gloucester and Ledbury railway, which was built on the line of the canal where it entered the parish at Ellbridge but then diverged on a more westerly course up the valley of the Ash brook. Oxenhall was served by Newent station just over the parish boundary near Ellbridge, and a halt was opened in 1937 at Four Oaks where the railway left the parish on the north. Passenger services ceased in 1959 and the railway was closed in 1964. (fn. 39) Among surviving remains on the line of the canal are a lock and its keeper's brick cottage of 1838 east of Oxenhall church. (fn. 40)

POPULATION

Eight agricultural tenants were recorded on Oxenhall manor in 1086 (fn. 41) and 23 people were assessed for the subsidy in Oxenhall in 1327. (fn. 42) A figure of 24 households given in 1563 (fn. 43) seems a considerable underestimate given the number of small farmhouses that existed at that date. Population estimates of 50 families in 1650 (fn. 44) and around 200 inhabitants c.1710 (fn. 45) seem to accord more accurately with the evidence of the settlement pattern at those later dates. About 1775 a figure of 202 people in 46 families was given, apparently by an exact local enumeration. (fn. 46) During the next 35 years there appears to have been proportionately a rapid growth, with the declining number of small farmhouses more than offset by the building of new cottages in outlying parts of the parish: 313 people were returned in 1801 and 347 in 1811. The population then began a steady fall, reaching 218 in 1891 (the boundary change of 1883 having added only 28 people on the few farms of the detached lands of Pauntley). During most of the next century it diverged little from that figure, 223 people being enumerated in the parish in 1991, but by 2001 it had fallen to 185. (fn. 47)

58. Lock Cottage

SETTLEMENT

Oxenhall has no village and is unlikely ever to have had one. The ancient pattern of settlement was scattered small farmsteads. In 1659 a manorial survey (fn. 48) enumerated 21 dwellings on the small copyhold farms that formed the core of the tenantry, but several of the copyholds, though having only one house, were described, following an ancient description, as comprising two or three messuages. Altogether the survey suggests that the copyholds had at one time included 31 houses, the number being reduced by a process of amalgamation of farms into larger units begun in the late Middle Ages. That process continued during the next two centuries and by 1841 the sites of only about a third of the copyhold houses recorded in 1659 were still occupied. The total of dwellings listed in 1659, including the houses of some freehold farms and various leasehold cottages, mainly on the fringes of Hay wood, was 45, and c.1710 the parish was said to contain 40 houses. (fn. 49) Later, although the number of farmhouses was reduced, new cottages were built on the edge of woodland and elsewhere in the parish, so that Oxenhall had 63 inhabited dwellings in 1831. (fn. 50)

ANCIENT SETTLEMENT

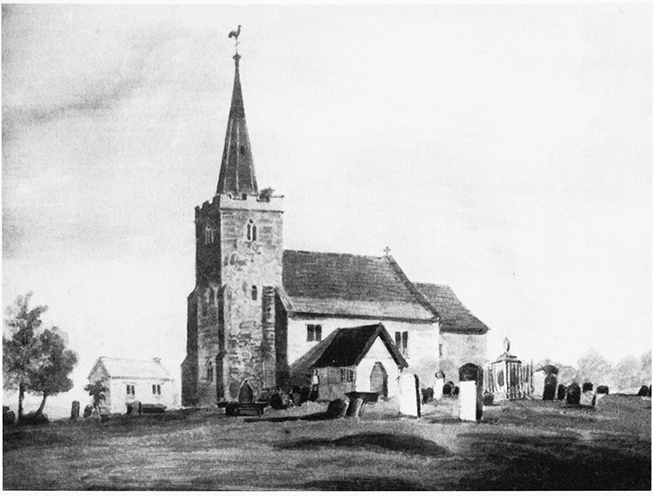

Oxenhall's parish church occupies an isolated site in the south of the parish on a small, well-defined hill above the valley of the Ell brook. A church house standing at the edge of the churchyard, (fn. 51) built probably in the late 1550s when a legacy was left for that purpose, (fn. 52) was pulled down in 1841 (fn. 53) when a small school building was built across the lane from the church. (fn. 54) On higher ground further north, near the junction of a number of lanes including Coldharbour Lane leading from the Newent–Dymock road in the east and Holder's Lane leading from Hillend on the north boundary, are two ancient sites: Hilter Farm (formerly Yeldhall) was possibly the site of an early medieval manor house and Oxenhall Court was the farmhouse of the rectory estate. (fn. 55)

59. Oxenhall church from the south with the church house in the background c. 1840

The main spread of ancient farmhouses lay in the west of the parish in the area traversed by lanes leading from the parish church towards Gorsley and from near Hilter Farm to Shaw common. That area once had a more complex pattern of closes, interspersed by coppices, orchards, and minor tracks to the farmhouses. Among the few surviving houses, White House Farm on the lane to Gorsley was recorded from 1443 (fn. 56) and was in 1659 the centre of the largest copyhold farm on the manor. On higher ground north of that lane stands a farmhouse once called Briary House but later known as Peter's Farm from the surname of the family that occupied it in 1549 and until 1688 or later. (fn. 57) South-west of Peter's Farm, on a small hill where the underlying sandstone outcrops, stood a farmhouse called the Rock (later Hilltop), (fn. 58) and near the head of a small stream c.500 m north-west of White House was another called Goodwins (later Woodens); (fn. 59) both those houses survived as the centres of small farms in 1775 (fn. 60) but were demolished before 1841. Another small farmstead called Carter's, occupied by a branch of the Hill family in 1549 and until the late 17th century, (fn. 61) stood south-east of White House beside the lane leading from the parish church. (fn. 62) It survived until the mid 19th century and was probably removed in the 1870s when a coal mine (Newent colliery) was established close to its site. (fn. 63)

Field names in the south-west of the parish recall and probably mark the sites of other copyhold farmhouses recorded in the mid 16th century by the names 'Smith's', 'Loveridge's', 'Yardsley's', and 'Woodnutt's (later Ashbrook)'. (fn. 64) Way (or Wain) House, on the north side of the lane to Shaw common, was recorded from 1509 as the centre of a small freehold but was acquired c.1607 by the manor estate, (fn. 65) on which it remained a smallholding. (fn. 66) In 2006 the cottage at the site had a small commercial vineyard attached. Two copyhold farmhouses in the area to the north of the same lane were both known as Thraper's in the 17th century. One was in decay by 1713 but the other, then known as Greenaway's (fn. 67) from an earlier tenant, remained the centre of a small farm in 1775; there was still a cottage on the site in 2006. On the north boundary of the parish a dwelling called the Shaw was the centre of a copyhold that included Betty Daw's wood (formerly Cumming's grove); the Cummings (Comin) family were its tenants in 1602 (fn. 68) and until the late 18th century.

On the generally higher and more open land in the north of the parish the surviving farmsteads include Holder's Farm, standing on the east side of Holder's Lane, and Pella Farm, west of Holder's Lane. Both were recorded from the 1440s (assuming Pella to be the house then called Pilleysplace), (fn. 69) and in 1659 each farm comprised the land of three former tenant houses but only one farmhouse remained on each. One of the sites absorbed into Holder's farm was probably at a place called Sandfords (fn. 70) (later Sandford Orchard) near Hillend green, and one of those absorbed by Pella at a field called Woodhall (fn. 71) on the parish boundary north of Pella farmhouse. The houses of three of the smaller copyholds of the 16th (fn. 72) and 17th centuries — Backs, held for many years by a branch of the Wood family, (fn. 73) Cook's Place (later Wilses), and Boar's Place (fn. 74) — stood further south in the upland fields bounded on the west by Ash brook and on the east and south-east by Holder's Lane. By 1775 all three had been absorbed into Hilter farm and only a house called Little Pella (Pellow) survived in that area; it too had been demolished by 1841. In the mid 17th century several of the tenants farming parts of the lord of the manor's park had dwellings in the north-east of the parish. One, held by Henry Wetherlock, (fn. 75) was probably the farmhouse later called Waterdynes or Waterlocks, north of Holder's Farm. (fn. 76) In 1775 there was also a small farmhouse in the former parkland east of Waterdynes, close to the parish boundary. It was demolished before 1882, by which time the owners of the manor had built a larger house called the Parks near by, within Newent. (fn. 77)

In the 17th century a few houses stood east of Hilter Farm where Coldharbour Lane crossed the stream in the valley later used as the course of the canal. On the east bank of the stream, in an area then known as Overbrooks or Upbrooks End, a branch of the Wood family had a copyhold farmhouse called More's Place; (fn. 78) it was possibly the house that in 1775 stood at the end of the pool that the stream forms south of Coldharbour Lane. Dwellings called in 1659 Hathaway's and Overbrooks are evidently represented by the two 17th-century houses (Brook Cottage and its neighbour) which stand by the crossing on the north side of the lane. They were among the few small independent freeholds in the parish and remained so until the 1820s when bought by Samuel Beale, owner of Oxenhall Court farm; his successors sold them with the farm to the lord of the manor in 1859. (fn. 79)

In the south-east part of the parish there were relatively few dwellings. Most of the land there belonged in the late Middle Ages to a large freehold called Marshall's, based on a house near Ellbridge. In the early 17th century, when the lord of the manor built an ironworks at Ellbridge, the farm was broken up, the name Marshall's passing to a farmhouse established at the north end of its land, on Coldharbour Lane. Adjoining the remains of the ironworks at Ellbridge is a substantial house once called the Furnace (later Oakdale House) occupied by members of the Onslow family, owners of the manor in the 19th century and the early 20th. Winter's Farm, on the lane leading from the Newent–Dymock road towards Oxenhall church, was another site occupied by the late Middle Ages. (fn. 80) Lambsbarn, on the east side of the Newent–Dymock road, was so called by 1693, (fn. 81) taking its name from a former owner of the adjoining group of fields. A small farmhouse was added beside the barn before 1841.

The detached part of Pauntley added to Oxenhall in 1883 has a number of ancient farmsteads. (fn. 82) Hill House Farm, on a low hill overlooking the confluence of the Ell brook with the tributary that marked the old parish boundary, is on a site apparently occupied from the 13th century. Its late medieval tenants, the Hills, probably took their name from the location and may have been the ancestors of the many branches of the family who later farmed in the Oxenhall area. Kew's Farm, on the boundary with Newent close to Kilcot, and Crooke's Farm, further east, were both recorded from the early 15th century, and Lower House, across Ell brook from Hill House Farm, had been established by the 17th century. A few other dwellings were recorded in the mid 17th century: they included two cottages in a close called Peppercorn, between Hillhouse grove and the brook that formed the west boundary of the detached lands of Pauntley, and a house called Spillman's, on the east side of the grove. (fn. 83) All had been demolished by 1775. (fn. 84)

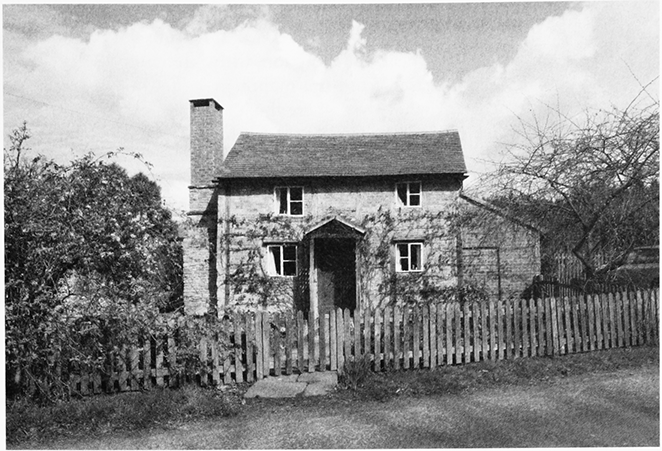

60. Quince Cottage near Shaw common

SETTLEMENT IN MODERN TIMES

The building of cottages in outlying parts of Oxenhall, mainly on the fringes of its western woodlands, was a feature of its early modern history, though in no part did it create a hamlet of any size or compactness. By 1615 seven cottages were spaced out around the southern edge of Hay wood in closes of land varying from 3 to 8 acres. (fn. 85) Held from the manor by leasehold rather than copyhold, they were presumably of fairly recent origin. The encroachment of Shaw common, north-east of Hay wood, had begun by the 1640s, when two cottages there were leased under the manor, (fn. 86) and in 1659 there were at least two more further north, adjoining Oxenhall wood. In the course of the next century almost all of the cottages along the south side of Hay wood vanished. Presumably their abandonment was not the result of policy by the landlords, the Foleys, who permitted cottage development in other parts of their estate and perhaps actively encouraged it to provide a labour force for cording and charcoaling their coppices. The Foleys granted leases of cottages on encroachments on Shaw common in the early and mid 18th century, (fn. 87) and in 1775 there were seven dwellings there and another three further east on waste beside the lane leading back towards the centre of the parish. (fn. 88) Others were added later, and by 1851 there were 10 households living around Shaw common and another 12 in the area, then distinguished as Shaw green, around the lane further east; (fn. 89) presumably some of the cottages were then in more than one occupation.

One cottage at Shaw common in 1775 was rebuilt on a larger scale as the centre of Pound farm, one of the main farms of the manor estate in the 19th century. It was named from the pound established near by for livestock found straying in the woods; (fn. 90) the original cottage at the site was possibly that occupied by the lord of the manor's woodward in the 17th century. (fn. 91) Most of the dwellings in the area were abandoned and demolished in the later 19th century and the 20th, and in 2006 the only survivors on the former common were Pound Farm and a cottage near by, once the centre of a smallholding called Little Pound farm, and four cottages further east, around the entrance of the lane leading towards the centre of the parish. One of the latter, adjoining the east side of a grove called Haine's Oak wood, was occupied by the manor estate's head gamekeeper in the 19th century. (fn. 92) It became known as Crown Lodge after the Oxenhall woods passed to Crown estate in 1914 (fn. 93) and as Old Crown Lodge after the mid 20th century, when a new lodge and small forestry depot were established to the north of Pound Farm.

A few cottages were built, widely spaced out, on the Oxenhall side of the lane that marks the north boundary of the parish. By 1775 there were two at Hillend green, where one near the junction with Holder's Lane had been leased from the manor in 1749, (fn. 94) and another three further west where the lane adjoined Wetherlock's grove. A small and more concentrated group of cottages was established on freehold land near the road junction at Three Ashes on the east boundary. One was built shortly before 1733, and Richard Peters, a wheelwright, added four others on an adjoining plot that he bought in 1815. (fn. 95) There were six households at Three Ashes in 1851. (fn. 96) In 1856 a larger house was built as a vicarage near by, on the Newent–Dymock road. (fn. 97)

The 20th century made little impact on the settlement pattern of Oxenhall. Six council houses were built adjoining Four Oaks, a hamlet on the north boundary mainly within Dymock, during 1953 and 1954. (fn. 98) Later in the century a few private houses were added in various parts of the parish, and some of the farms were given modern dwellings after old farmhouses were sold away from the land.

BUILDINGS

Most of the sites of the farmhouses in Oxenhall and the adjoining part of Pauntley can, as described above, be traced from the 17th century and several from the 15th, though the present appearance of most of the houses is the result of remodelling or rebuilding in brick in the late 18th century and the early 19th. For the majority, the farmhouses on the Oxenhall manor estate, a fairly standard pattern was used, but Crooke's Farm, the principal freehold, was transformed at that period into a small country house.

Crooke's Farm stands on a site that slopes steeply up from almost west to east and the house platform has been terraced, perhaps in the 17th century when the house was enlarged to accommodate parallel northern and southern ranges at different levels. Its northern range incorporates at its western end the cross wing of a substantial medieval house, which may have had an H plan. Built probably in the first quarter of the 15th century, the two-storeyed wing is of high quality with part of its western wall and large western chimneystack built of stone and the gable end timber-framed, partly close-studded. The northern end was probably the principal chamber, comprising four narrow bays open to a roof which has cusped windbraces; at the apex the principals are cusped and together with curved struts springing from the collar form a trefoil. The southern end has remains of slightly simpler trusses, of which one at each end and some re-used rafters are smokeblackened, perhaps the result of an 18th-century fire. (fn. 99) There is another late medieval farmhouse at Furnace Farm, apparently the house of the substantial freehold called Marshall's. (fn. 100) Originally on an L plan, (fn. 101) it may have been built in the late 15th century, and has a two-bayed hall with arch-braced trusses and cusped windbraces.

Rebuilding in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

In the mid 17th century, probably before 1672 when it was assessed on 8 hearths, (fn. 102) Crooke's Farm was enlarged. An east–west range was built at the northeastern end of the cross wing, perhaps replacing or incorporating the medieval hall range, and a large stack with six diamond shafts was inserted within its eastern end. The eastern wing was probably rebuilt or remodelled then. (fn. 103) A parallel two-storeyed, twobayed range with western chimneystack and staircase was added at a right angle to the other, south-eastern end of the cross wing, almost detached from it. The gap between the two east–west ranges and the difference in floor levels were reconciled by inserting a broad dog-leg staircase with turned balusters and ball finials between them. In the farmyard to the north-east a barn was built. At Furnace Farm at the same period the medieval hall was floored and a large stack built at the western end.

Other farmhouses were built anew with timber frames in the 17th century, including Winter's, Lower House, Kew's, White House, and Oxenhall Court (the rectory farmhouse). Winter's Farm is an L-plan, two-storeyed house with a tall, stone-built cellar under the cross wing to take advantage of the site's fall. Lower House is on a similar plan but of 1½ storeys. Two of its three rooms are divided by a stack, and the beam over one fireplace has a rough inscription of 1619. Kew's Farm, (fn. 104) of three bays and two storeys, was probably built in the mid to late 17th century and has brick infilling. Contemporary farm buildings include an attached cider house and a barn which encloses a farmyard on a south-eastern terrace. White House Farm was built on a similar plan but had one storey with additional rooms within the roof. Sandstone was used, perhaps later, for the eastern gable wall which may have curtailed the house that in 1672 was assessed on 5 hearths. (fn. 105) Some of the hearths may have been in detached buildings, for in 1659 White House was described as a house of four bays, with an old two-bay kitchen, a two-bayed (cider)-mill house, and a four-bayed barn; (fn. 106) one of those outbuildings may have been the single-storeyed southern wing which was later joined to the house. Oxenhall Court seems to have been built with some stone outer walls and mullioned windows as an L-plan house, its main southern range being of three bays and two storeys and attic. Brook Cottage and the adjoining cottage, standing in Coldharbour Lane by the bridge over the disused canal, both timber-framed with large end chimneys, are surviving examples of smaller dwellings of the period.

61. Kew's Farm, near Kilcot

Rebuilding after 1750

White House Farm was subjected to extensive work in the mid 18th century, at least some of it in 1752 and 1761 when much building material, including brick and tile from Gorsley, was supplied by the Foley estate. (fn. 107) The timber frame was faced with brick, the high end of the house raised to two storeys, and the roof hung with clay tiles. Much of the fabric of the outbuildings may be of similar date. Marshall's Farm, on Coldharbour Lane, combines brick and stone in a shallow-roofed building that could be of the 18th or early 19th century. Elsewhere 18th-century work seems to have been confined to outbuildings, and to building by squatters of cottages with light timber frames, such as at Quince Cottage, near Shaw common, (fn. 108) and the former Way House (in 2006 St Anne's Vineyard), or of brick alone, as at Little Pound Farm at Shaw common.

The farmhouses at Holder's and at Hilter were completely rebuilt in brick c.1800. At Holder's the work was probably in two stages close in date, for the front range, which has a plain two-storeyed, threebayed façade with segmental-headed casement windows and end stacks, appears to have been raised slightly when a back range was added. (fn. 109) The L plan was infilled later by a lean-to dairy. At Hilter Farm the old farmhouse was replaced by a house similar in plan and elevation to that at Holder's, but larger and with an extra storey. It was remodelled later in the 19th century when it was given a roof with overhanging eaves and a front porch. Blue brick diapering on the western gable wall was repeated in a cider house to the east. Pound Farm at Shaw common was rebuilt in the late 19th century, probably in the 1870s when it was occupied by William Onslow, a younger son of the lord of the manor, (fn. 110) and is a late version of the same pattern as Holder's.

62. Holder's Farm from the south

Crooke's Farm was made to resemble a small country house in the late 1820s or 1830s; it had for some time been leased as a farmhouse, as it was again for many years afterwards, but possibly the owner, Benjamin Hooke, intended at that time to use it as a residence. (fn. 111) The northern façade was rendered and given sashes and a Doric portico, and much of the roof was reconstructed. The main rooms were fashionably decorated and given chimneypieces and doorcases with reeded architraves and lions' head paterae, as on the portico. The lowest flight of the staircase, which had apparently already been replaced after a fire in the early 18th century, (fn. 112) was remade as a plain swept flight.

Alterations to other farmhouses were minor. Winter's was reroofed (one rafter has a date 1860), a gable wall and large chimneystack were rebuilt, and a veneer of Victorian style was applied. Kew's was doubled in size by the addition to the north of two plain brick piles of rooms, and Lower House was cased in brick in the late 19th century when one bay was extended and barn and stables of Gorsley stone provided. The northern front of Oxenhall Court was refaced in brick and the angle of its two ranges filled with service rooms. At Furnace Farm, where the back range was removed before 1841 and the house became two cottages, (fn. 113) the high end of the surviving range was rebuilt in brick.

Most farms were provided with brick outbuildings in the early and mid 19th century. Some timberframed buildings were retained or improved, for example a barn at Pound Farm, and at Holder's a 17th-century bull house (attached to a brick barn which before rebuilding was possibly the five-bayed barn mentioned there in 1659) and a long, low timber-framed range. (fn. 114) New work at Hilter Farm included a courtyard of brick buildings close to the house, and a six-bayed barn which stood until the mid 20th century. (fn. 115) At Oxenhall Court a long range was built to incorporate a pigsty, stable and hayloft, cider-mill house, five-bayed threshing barn, and cart shed: a cider mill on site is dated 1838. Part of that range of building was converted to residential use in the late 20th century. The houses most extensively altered in the late 20th century were White House and Winter's Farm after their farmland was sold.

MANOR AND ESTATES

Oxenhall formed a separate manor from before the Norman Conquest, and for most of its history the manor estate included the bulk of the ancient parish. Some independent freeholds (fn. 116) emerged by the late Middle Ages, including a block of land on the east side of the parish owned by the Porter family. Most of those lands were, however, bought in later by the Foley family of Stoke Edith (Herefs.), which acquired Oxenhall manor in 1658. During the 18th and 19th centuries the only farm of any size in the ancient parish outside the manor estate was the rectorial glebe based on the farmhouse called Oxenhall Court. The pattern of landholding changed radically with the sale of the manor estate in 1913 when most of the farms were bought by the tenants. In the detached portion of Pauntley added to Oxenhall in 1883 the most significant farm was Crooke's, which belonged to the Hooke family by 1435 and remained in its possession in the early 21st century.

OXENHALL MANOR

In 1066 Oxenhall manor was held from Earl (i.e. King) Harold by Thorkell. In 1086 it was part of the extensive Gloucestershire estates of Roger de Lacy, (fn. 117) having presumably belonged to his father Walter (d. 1085). After Roger's rebellion and banishment in 1096 his lands were forfeited and granted to his brother Hugh de Lacy. (fn. 118) Oxenhall had apparently been subinfeudated by 1202 when the tenants of Walter de Lacy's honor included the 'lady of Oxenhall', (fn. 119) and in 1236 the widow of Stephen of Evreux held it from Walter. (fn. 120) The overlordship has not been found recorded again until 1335 when the manor was held from the heirs of Geoffrey de Genevyle. (fn. 121) By 1358 Roger Mortimer, earl of March, was overlord, and his right descended with his earldom (fn. 122) to be assumed by the Crown on the accession of his descendant as Edward IV. (fn. 123)

By 1251 Oxenhall manor had passed to William of Evreux. (fn. 124) After his death at the battle of Evesham in 1265 it was granted for life to his widow Maud, (fn. 125) who in 1292 approved a grant by a younger William of Evreux of his reversionary right to William de Grandison and his wife Sibyl. (fn. 126) William de Grandison was in possession of the manor in 1316 (fn. 127) and died c.1335 to be succeeded by his son Peter. (fn. 128) Peter (d. 1358) (fn. 129) settled the manor on his nephew Thomas de Grandison (d. 1375) with remainder to Elizabeth le Despenser, whose son Guy de Brian succeeded at Thomas's death. (fn. 130) After Guy's death in 1386 his widow Alice retained Oxenhall manor (fn. 131) until her death in 1435, when the heir was Elizabeth Lovell. (fn. 132) Elizabeth died in 1437, leaving as heir to Oxenhall her grandson Humphrey FitzAlan, earl of Arundel, (fn. 133) who died a minor in 1438. In 1445 Oxenhall was settled on James Butler and his wife Amice, evidently in her right. She died in 1457 (fn. 134) and James, who had been created earl of Wiltshire in 1449, retained the manor until his execution and attainder after the battle of Towton in 1461. The following year it was included in an extensive grant of forfeited Lancastrian lands to Walter Devereux, created Lord Ferrers, who may have retained it until his death at Bosworth in 1485. (fn. 135) The manor passed to Henry Percy (d. 1489), earl of Northumberland, perhaps by virtue of his marriage to Devereux's niece Maud Herbert. (fn. 136) In 1492 it was in the hands of the Crown during the minority of the earl's son and heir Henry, (fn. 137) who came of age in 1499. That Earl Henry (d. 1527) was succeeded by his son Henry, who sold Oxenhall to the Crown with other Gloucestershire possessions in 1535. (fn. 138)

In 1544 the Crown mortgaged Oxenhall to a group of London merchant tailors, of whom Thomas Broke (fn. 139) owned it at his death in 1546. He left it to Richard Tonge but his will was voided and it was given to his sister Joan Arrowsmith. (fn. 140) She conveyed Oxenhall in 1547 to William Grey, Lord Grey of Wilton, (fn. 141) and he conveyed it in 1551, with his manor of Kempley, to William Pigott (d. 1553). His widow Margery (fn. 142) retained it in 1579, (fn. 143) when his son Leonard settled the reversion on the marriage of his daughter Anne to Samuel Danvers (fn. 144) of Culworth (Northants). The couple had apparently succeeded to Oxenhall by 1586 (fn. 145) and Anne and her second husband Henry Finch, of Little Horwood (Bucks.) and later of Kempley, were dealing with the manor in 1600. (fn. 146) Two years later Finch bought out the reversionary right of Samuel Danvers, Anne's son by her first marriage, (fn. 147) and at his death in 1631 he was succeeded by his son Francis Finch, (fn. 148) later of Rushock (Worcs.), who in the late 1640s and early 1650s held manor courts for Oxenhall and granted leases jointly with John Blurton of Redditch (Worcs.), perhaps a mortgagee. (fn. 149) Francis, who set up ironworks at Ellbridge, incurred large business debts and in 1658 he sold the manor to the ironmaster Thomas Foley. (fn. 150)

Thomas Foley shortly afterwards bought the adjoining manor of Newent, with which Oxenhall descended in the Foleys and their successors, the Onslows, for the next two and a half centuries. (fn. 151) In 1775 the Oxenhall estate comprised 1,668 a., (fn. 152) and in the mid 19th century there were eight principal farms totalling 972 a., various smallholdings, and 480 a. of woodland. (fn. 153) The estate was put up for sale by Andrew Richard Onslow in 1913 and most of the farms, including Holder's, Winter's, Peter's, Pella, White House, and Waterdynes, were bought by the sitting tenants. (fn. 154) In 1914 639 a. of woodland in Oxenhall and Dymock was sold, with Little Pound farm, to Archibald Weller of Malvern; he sold the woods in the same year to the Crown (fn. 155) and they were subsequently managed as part of the large tract known later as Dymock Woods. (fn. 156) A.R. Onslow (d. 1950) retained the manorial rights of Oxenhall. (fn. 157)

As suggested below, the original manor house of Oxenhall may have been at Hilter Farm. A capital messuage recorded on the manor in 1358 (fn. 158) and worth nothing in 1435, when it was waste, (fn. 159) was more likely in Oxenhall park in the north-east corner of the parish. There it was said c.1700 that a house had once been a residence of the Grandisons. (fn. 160) A field called Moat field, north-east of Waterdynes Farm, may have been its site. (fn. 161)

OTHER ESTATES IN OXENHALL

Hilter Farm

A man called Roger of the Guildhall (de la Ghildhalle) witnessed Oxenhall deeds in 1316 (fn. 162) and in 1327 Roger 'atte Yeldhalle' and two others similarly surnamed were assessed for tax in the parish. (fn. 163) Those men evidently occupied a building or buildings at the prominent site near the centre of the parish where in the 17th century stood the farmhouse called Yeldhall; the name later mutated to Illto or Ilthall and finally, by the early 19th century, to Hilter (or Hilters) Farm. (fn. 164) If the name Guildhall was being used in its original sense — as a building where payments or dues were rendered (fn. 165) — it seems likely that Hilter was the site of the original manor house, perhaps alienated or leased away by the lords before the early 14th century. The existence of a dovehouse among the buildings at the site in the 17th century and a coney warren in one of its fields (fn. 166) further supports the suggestion of former manorial status.

Yeldhall (later Hilter) Farm passed to John Hill, who sold it in 1596, together with his Hill House estate in Pauntley, to Sir Edward Winter, owner of Newent manor. (fn. 167) In 1657 the Winters sold Yeldhall, with 25 a. of land adjoining, to Thomas Rogers and in 1668 he sold that estate with other lands to the lord of Oxenhall manor, Thomas Foley, who as part of the transaction granted it back on a lease for lives. Rogers died in 1671 and his son William surrendered his life interest to Paul Foley in 1680. (fn. 168) The house, which was assessed for tax on six hearths in 1672, (fn. 169) was apparently then the largest in the parish. It remained the centre of one of the principal farms on the manor estate until the sale of 1913, (fn. 170) but ceased to be a farmhouse in the 1970s when the farmland was sold to a fruit farmer, who built a new house near by. (fn. 171)

Marshall's and Winter's Farms

An estate called Marshall's farm, based on a house near Ellbridge, may have derived from an early medieval subinfeudation: at the death of its owner in 1612 it was said to be held from the lord of Oxenhall manor by fealty and suit of court but a second inquisition revised that finding to tenure by knight service from the Crown as overlord of the manor. (fn. 172) Roger the marshal (mareschal) who was assessed for tax at a high rate at Oxenhall in 1327 (fn. 173) was presumably an early occupant, but the estate has not been found recorded before 1525, when with Winter's farm it belonged to Arthur Porter. (fn. 174) Possibly the two farms had been acquired by his father Roger Porter (d. 1523) of Newent, who was steward of Oxenhall manor for the earl of Northumberland. (fn. 175) Both farms descended, presumably with Arthur's extensive estate in Newent, to his grandson Sir Arthur Porter. (fn. 176) In 1604 Sir Arthur with others, presumably trustees or mortgagees, sold Marshall's farm (110 a.) to Christopher Hooke, its tenant since 1586. (fn. 177) Christopher died in 1612 and, subject to his widow Anne's third share in dower, the farm passed to his son Thomas. (fn. 178) Thomas sold it in 1634 to Edward Clarke of Newent, a haberdasher; it then included Ellbridge mill which later, under a lease by Clarke, Francis Finch converted to form part of his ironworks. In 1647 Clarke settled the farm on the marriage of his son Edward with Mary Chinn. (fn. 179)

By 1659 the farm had been dispersed among several owners, and the farmhouse, then styled Marshall's or Ellbridge, was said to belong to William Chinn. (fn. 180) In 1672, however, the younger Edward Clarke confirmed to Paul Foley a grant he had formerly made of the house and Ellbridge mill to Paul's father Thomas. (fn. 181) The house was evidently the remodelled 15th-century farmhouse (fn. 182) that was known later as Furnace Farm from the nearby ironworks, though it stands some way north of that site on the west side of Furnace Lane. Furnace Farm remained part of the manor estate after the mid 17th century. It was attached to Winter's farm in 1775 (fn. 183) and later, reduced in size, it was occupied as farm cottages. (fn. 184) In 1913 the house with a farm of 105 a. was bought by the widow of the former tenant James Lodge, (fn. 185) and in 2006 it was owned and farmed by Mr R.G. Heath. Another former part of Marshall's farm passed to a branch of the Hill family, which sold it to the Foleys in 1758, (fn. 186) and another former part, adjoining Coldharbour Lane west of the Dymock road, acquired its own small farmhouse, which assumed the name Marshall's Farm. The latter was owned by members of the Clarke family in the mid 19th century (fn. 187) but was added to the Oxenhall manor estate in 1890. (fn. 188)

Winter's farm, based on a farmhouse on the lane running between Oxenhall church and the Newent–Dymock road and originally including a second farmhouse called Gillhouse, was sold by Sir Arthur Porter in 1604 to Roger Hill. It passed to Roger's son Arthur Hill of Highnam, who settled the 70-a. farm in 1635 on the marriage of his daughter Martha and Henry Stranke of Highnam. (fn. 189) In 1659 Winter's was held by a lawyer William Sheppard (fn. 190) and in 1677 and 1688 by Joseph Morwent of Ledbury. (fn. 191) Nevertheless, it descended to the Strankes' grandson, John Rawlinson of Dartmouth (Devon), who sold the farm in 1718 to Thomas Foley, the lord of the manor. (fn. 192) From that time until the sale of 1913 it remained one of the principal farms of the manor estate. (fn. 193)

Oxenhall Rectory and Oxenhall Court

In the mid 12th century the tithes of Oxenhall belonged, probably by gift of one of the Lacy family, to St Guthlac's priory, Hereford, which had confirmation of its right from the bishop of Hereford. (fn. 194) By 1291, however, Oxenhall church, apparently with all its tithes and profits, belonged to the Knights Hospitaller, (fn. 195) who attached it to their preceptory of Dinmore (Herefs.). In 1338 the church, including four 'bovates' of glebe land, was let at farm under the preceptory for £10 a year. (fn. 196) Following the Dissolution the rectory estate was held by the Crown before being granted in 1548 to Robert Curzon, one of the Barons of the Exchequer. (fn. 197) He conveyed it the same year to John Bridges (d. 1561), with whose Boyce Court estate, in Dymock, it passed to his nephew Humphrey Forster and then to Humphrey's son Giles. (fn. 198) Giles incurred debts in his post of royal receiver for several Midland counties, leading to the Crown taking possession of the rectory estate (fn. 199) and conveying it in 1610 to feoffees to use the profits for repayment. Nevertheless the same year Giles made a conveyance of the estate to William Burrows, who in 1612, together with Sir Clement Throckmorton, assignee of the Crown's feoffees, sold it to Sir Robert Baugh (also known, apparently, by the surname Banister), John Worsley, and Launcelot Salfield. Those parties sold it in 1625 to Nicholas Roberts, (fn. 200) from whom it descended until 1801 with an estate in Westbury-on-Severn in the Roberts and Colchester families. (fn. 201)

The rectory included all the tithes of the parish with a glebe farm, described in 1613 as comprising a parsonage house (that later called Oxenhall Court), a tithe barn, three orchards, seven inclosed fields, and a meadow; there were also some outlying parcels of land and woodland leased separately, (fn. 202) as was the case later. The whole rectory was valued at £30 in 1600, (fn. 203) and in 1629 Nicholas Roberts granted a lease to John Beale at the rent of £70. In 1708 the rectory was leased to John Dobbins, who then also tenanted the adjoining Hilter farm on Oxenhall manor. (fn. 204) In 1738, when Oxenhall Court farm comprised 74½ a., it was leased to Arthur Clarke, whose family remained lessees until the mid or later 19th century. (fn. 205)

In 1801 the trustees of John Colchester sold the rectory estate to Samuel Beale, an attorney of Upton upon Severn (Worcs.). (fn. 206) Beale died in 1840, having entailed it on his daughter Mary Symonds and her descendants, (fn. 207) and in 1841 she was awarded a corn rent charge of £440 a year in place of the tithes. (fn. 208) In 1857 Mary with other family members and Samuel's trustees sold Oxenhall Court and the rectory lands to R.F. Onslow, heir to the Oxenhall manor estate. (fn. 209) At the sale of that estate in 1913 Oxenhall Court farm was bought by George Gurney, (fn. 210) who still owned and farmed it in 1931. By 1939 the farmer was John Cummins, (fn. 211) and the Cummins family sold it in 1982 to Dr and Mrs P.H. Wright, the owners in 2006. (fn. 212) The tithe rent charge was retained by Mary Symonds (d. 1859) and passed to her daughter Mary Tennant (d. 1903) and grandson Edmund William Tennant (d. 1923), whose trustees held it until tithe redemption in the 1930s. (fn. 213)

ESTATES IN THE DETACHED PART OF PAUNTLEY

In 1086 Ansfrid of Cormeilles, lord of Pauntley, held a manor called Kilcot, extended at 1 hide. (fn. 214) Later evidence suggests that it included the whole of what became the detached part of Pauntley parish, lying south of Oxenhall, together with adjoining lands in Gorsley that belonged to Newent parish, though the evidence is rendered difficult to interpret by the overlapping, and probably changing, application of the place names Kilcot and Gorsley. In the late 12th century William de Solers, probably then lord of Pauntley manor, (fn. 215) made a grant of ½ yardland and 10 a. in Kilcot, which a later owner gave to Cormeilles abbey, lord of Newent. (fn. 216) In the mid 13th century Roger de Solers granted to Cormeilles all the rents and services owed by four tenants 'in Kilcot in the parish of Pauntley' as well as remitting to the abbey the rent from the estate alienated by William. Later, Richard, son of Walter de Solers of Pauntley, remitted all right in the lands Cormeilles held from him, except for royal service and a rent of 8s. (fn. 217) Those lands presumably comprised the ⅓ knight's fee 'in Gorsley' that in 1398 the prior of Newent, administrator of Cormeilles' Newent manor, was said to have held from the earl of March, the overlord of the de Solers family in Pauntley. (fn. 218) By that time the 8s. rent reserved to the lords of Pauntley under Richard's grant was paid from land on Newent manor known as the 'court of Gorsley', which adjoined and was sometimes itself regarded as lying within the detached part of Pauntley. (fn. 219) It is clear, however, that the rights that the abbey had acquired from the de Solers family extended also over the whole western part of the detached lands of Pauntley, for in 1419 farms there called Hill's Place (later Hill House) and Kew's, together with land called 'freres', were held from Newent manor as free tenancies by a family surnamed Hill. (fn. 220) Their estate presumably included holdings once of John 'de Monte' and Roger 'le Frere', two of the four tenants mentioned in Roger de Solers's grant. The eastern part of the detached lands of Pauntley, forming Crooke's farm, was probably not included in the de Solers' grants to Cormeilles, for the farm's owners held it directly from the lords of Pauntley.

Crooke's Farm

Crooke's farm, which was held from the lords of Pauntley by fealty and a small chief rent, (fn. 221) was recorded from the early 15th century. A tradition, recorded in the early 18th century, stated that the farm was given, together with a sword and the right to a coat of arms, to a member of the Hooke family who served in Henry VIII's French campaign and helped rescue the king after he was surrounded by the enemy. (fn. 222) A version of the tradition current by the mid 20th century maintained, however, that those events featured a Hooke who served with and aided Henry V at Agincourt. (fn. 223) An ancient sword which remains in possession of the family is thought to date from the early 16th century (fn. 224) but, as the Hookes held Crooke's by 1435, the second version seems more likely to contain an element of truth.

In 1435 Thomas Hooke and his trustees settled Crooke's farm, together with the site of a house called Callowhill (in Compton, Newent), on his son Thomas and his wife Margaret. The deed was witnessed by his overlord, Guy Whittington of Pauntley, (fn. 225) said to be the father of Margaret in family pedigrees, which trace a descent in direct line to Guy Hooke (fl. 1470) and Richard Hooke. (fn. 226) Richard Hooke was a large taxpayer in Pauntley parish in 1522, (fn. 227) and Christopher Hooke of Crooke's died c.1579, leaving his lands to his son Thomas. (fn. 228) The son was apparently the Thomas who had three servants in Pauntley at the muster of 1608 (fn. 229) and died in 1628, holding Crooke's and 60 a. in Pauntley parish and another 193 a. in adjoining parishes, including Callowhill and land at Mantley and Picklenash in Newent. He was succeeded by his son Edward (fn. 230) (d. 1651) and Edward by his son John (fn. 231) (d. 1705), who devised Crooke's to his grandson Philip Fincher and his heirs on condition they adopted the surname Hooke. (fn. 232) John's widow Anne may have retained the farm until her death in 1722, (fn. 233) and Philip was in possession in 1734. (fn. 234) It apparently passed later to Edward Hooke (d. 1762), who was succeeded by his brother Benjamin Hooke of Worcester, and from that period Crooke's farm was leased while its owners lived in Worcester or on their estate at Norton, near that city. From Benjamin (d. 1771) Crooke's passed in succession to his sons John (d. 1795) and Benjamin (d. 1796). John, son of the last Benjamin, succeeded but in 1826 he sold the farm to his younger brother Benjamin, (fn. 235) who also acquired lands near by in Newent, including Briery Hill farm, (fn. 236) a gift from his mother Elizabeth Hooke (d. 1823). (fn. 237) Benjamin (d. 1848) left his Gloucestershire estates to his second son John Brewer Hooke, but they passed later to his eldest son Thomas T.B. Hooke (d. 1898). Crooke's then passed in direct line to Thomas C.B. Hooke (d. 1942), Douglas T.H. Hooke (d. c.1971), Michael R.D.H. Hooke (d. 2004), and Mr Richard Hooke. The family returned to live at Crooke's Farm in the 1970s, but in 2006 the farmland, comprising c.100 a., remained on lease. (fn. 238)

Hill House farm

Hill House farm, in the west of the Pauntley lands, was owned by Walter Hill (d. c.1419). Kew's farm, lying further south, was then in the same ownership, (fn. 239) but in later centuries usually followed a different descent. James Hill owned Hill House in 1539 (fn. 240) and, although John Hill sold it in 1596 to Edward Winter, lord of Newent manor, (fn. 241) members of the Hill family occupied it as lessees until 1640 or later. (fn. 242) The Winters sold Hill House, probably in the late 1650s, to John Brock, a carpenter. Brock died in 1668 leaving it to his wife Margery and then to his two daughters, (fn. 243) of whom Margery, wife of John Hill (d. 1687), later succeeded. Margery and her son Thomas Hill both died in 1712, leaving apparently as heir to the farm Margery's grandson John Warr. John came of age c.1717 and he settled Hill House, with the farm adjoining called Lower House, in 1731 on his marriage with his wife Anne. (fn. 244) He died in 1734 and she in 1765, when the property was evidently divided among the families of John's sisters, Mary Mayo, Margery Wood, and Margaret Phillips. (fn. 245) In 1780 Mary Mayo and her son Thomas sold a third share to Thomas Wood, (fn. 246) presumably Margery's heir, and in 1795 parts were owned by Thomas Wood and John Phillips, Margaret's heir. (fn. 247) Later Hill House farm in its entirety was acquired, together with Kew's farm, by Samuel Beale (d. 1840), owner of the Oxenhall rectory estate, and in 1857 Beale's family sold Hill House and 82 a. (including some fields of Kew's farm) to R.F. Onslow, heir to the Oxenhall manor estate. (fn. 248) At the sale of that estate in 1913 Hill House farm was bought by S. Goulding, (fn. 249) whose family remained owners in 2006.

ECONOMIC HISTORY

While it remained overwhelmingly an agricultural parish with a significant woodland economy, Oxenhall for a period contained ironworks. Later, canal construction was associated with the mining of coal locally. (fn. 250)

AGRICULTURE

To the Late Seventeenth Century

In 1086 the manor of Oxenhall had two ploughs and two slaves on its demesne, and the tenants were five villans and three bordars with five ploughs between them. Three burgesses in Gloucester were attached to the manor. (fn. 251) In 1335 the demesne comprised one ploughland and 3 a. of meadow. By 1386 the demesne ploughland had reduced in value, from 20s. to 16s., but the meadow, extended then at 6½ a., had increased in value, from 14d. to c.20d. per acre. (fn. 252) In 1435 the demesne arable comprised two ploughlands and was valued at the same total sum as in 1386, (fn. 253) presumably reflecting the falling in of tenant land to the lord and the decline in corn prices. According to the 14th-century extents the third part of the demesne arable that was left fallow each year, and the whole of it after the harvest, lay in common, suggesting that the demesne formed part of a fairly extensive tract of open fields. By the mid 17th century, however, the manor owned only a group of inclosed fields, lying in the southern part of the parish, bordered on the north by the lands of the rectory farm (Oxenhall Court) and the freehold called Hilter and on the east by the lands of the freehold called Winter's. That area contained fragments of open fields in the early modern period and may have been the location of larger open fields, perhaps inclosed in the late Middle Ages by a collaboration of the lords of the manor and the owners of those three other estates. In 1659 the manor closes in that area — the Woolastons lying between Oxenhall Court farm and the road from the parish church to Gorsley, Dropping Orchard south of that road, fields known later as Church fields adjoining the church, Hornifords meadow and Broad meadow on the north side of Ell brook, and lands called the Hides south of the brook — were on lease among manor tenants and other landowners. (fn. 254) In the 14th-century extents the demesne meadowland also was said to lie in common after the hay harvest, so part at least of the meadows bordering Ell brook was presumably once farmed in common.

In 1335 there were free tenants on the manor owing rents of 60s. a year and customary tenants owing rents of 13s. 4d. (fn. 255) By 1358 the figures were 100s. and 42s. 6d., (fn. 256) the latter increase presumably the result of the commutation of unwanted labour services. A process of amalgamation of customary tenancies under way in the late Middle Ages is reflected in the copyholds that formed the main class of manor tenancies in the 16th and early 17th century: the descriptions given to them indicate that most then incorporated the lands once attached to two or three separate holdings. In 1659 the manor contained a total of 24 copyhold farms. The largest, based on White House Farm, comprised 66 a., four others, including those based on Holder's and Pella Farms, had between 50 and 56 a., another based on Briary House (later Peter's Farm) had 32 a., and the remainder were under 30 a. There were also leaseholds, most of them small and based on cottages adjoining Hay wood but including some larger ones comprising parkland, woodland, and former demesne lands. (fn. 257) Under the Foleys in the later 17th century copyhold tenure was phased out, but in most cases it was replaced by leasehold for 99 years or three named lives with heriots payable, so the change for the tenants was probably not that significant. (fn. 258)

Only fragments of open-field land survived into the early modern period. In 1635 Winter's farm included five 'doles' of arable in Pool field, which probably adjoined the east side of Oxenhall pool, (fn. 259) and at the same period a small open field called Six Acres lay in the valley of Ash brook south-west of the lands of Oxenhall Court farm. (fn. 260) It is that area of the parish, extending from Six Acres on the west to the land of Winter's farm on the east, that seems the most likely site of the larger system of fields that apparently existed in the 14th century. Six Acres remained uninclosed in 1775 when five tenants owned land there. By then known simply as 'the common field', (fn. 261) it was presumably the last uninclosed arable to survive in Oxenhall. The meadowland along the Ell brook was all inclosed by the mid 17th century, the manorial demesne having a large part and most of the copyholders small closes. (fn. 262) The woodland in the west of the parish was subject to common rights of the tenants in the 14th century, (fn. 263) but by the 17th century all but the area that later formed Shaw common was several to the lord of the manor. (fn. 264)

The sandy soil of much of Oxenhall favoured the growing of rye, rather than wheat, as the winter corn crop. (fn. 265) In parishioners' wills of the 16th and 17th centuries rye featured regularly in the form of gifts to family members and charitable bequests, (fn. 266) and rye, barley or other spring crops, and a fallow were the usual courses of the three-year rotation that continued as the practice in the early modern period. (fn. 267) Some wheat was grown, however, where the soil was suitable: (fn. 268) Woodens farm in the south-west part of the parish and Holder's farm in the northeast both had closes named Wheat field in the 1670s. (fn. 269) All or most Oxenhall farmers kept sheep in the 16th and 17th centuries, (fn. 270) though the lack of common pasture or large open fields must have restricted the flocks to modest proportions. A sheephouse was among new buildings put up at Oxenhall Court in 1630s by its tenant John Beale, (fn. 271) and in 1659 the outbuildings on four of the copyhold farms included sheephouses. (fn. 272) Cider was another staple product, with cider mills (must mills), presses, and casks (hogsheads and pipes) among items passed down in the farming families. (fn. 273) Most leases of farms in the late 17th and early 18th century provided for the planting of apple and pear stocks in each year of the term. (fn. 274) A writer at the start of the 18th century identified rye, wool, and cider as the main products of the parish. (fn. 275)

From c.1700

Under the Foley family the amalgamation of the tenant farms of the manor continued, though the groupings of lands sometimes changed over the years and the new farms were not all ring-fenced, suggesting that the process resulted more from the ambition of particular tenants rather than a policy of reorganization on the part of the landlords. (fn. 276) Two new farms were formed on the estate after the purchase of the freehold of Hilter and Winter's farms. In 1775 Hilter, comprising the former freehold with some manorial demesne lands and the land of several of the smaller copyholds, had 156 a. and Winter's, with most of the land in the south-east corner of the parish, had 155 a. Another five farms — White House, Peter's, Pella, Holder's, and Waterdynes — then had between 80 and 102 a., another six had between 39 and 51 a., and there were a few smaller holdings. (fn. 277) Oxenhall Court farm with c.75 a., tenanted under the lay rectors, was the only substantial farm in the parish remaining outside the manor estate. In the adjoining detached part of Pauntley most of the land had long been divided between three farms, Crooke's, which was tenanted under its owners by the late 18th century, Hill House, and Kew's. (fn. 278) Further modifications in the pattern of farms on the manor occurred later, probably during the prosperous period for farming during the Napoleonic Wars when several of the Oxenhall farmhouses were rebuilt. William Deykes, the Foleys' land agent, who lived in the parish during those years, (fn. 279) presumably directed those changes. The long leases were probably phased out and replaced by annual tenancies at that period. By 1841 Hilter farm had been enlarged to 215 a. by the inclusion of Pella farm, Holder's to 152 a., and White House to 130 a., and Pound farm, based on a house at Shaw common and formed from a number of smaller holdings adjoining the woodlands in the western part of the parish, had 117 a. Winter's then had 96 a., the rest of its land being farmed from a small house near the remains of Ellbridge furnace, and the other main farms on the estate were Peter's (103 a.) and Waterdynes (71 a.). (fn. 280) The Onslows, the Foleys' successors, continued the policy of buying in freehold land when it became available, adding to the estate Oxenhall Court and Hill House farms in 1857, Lambsbarn farm before 1864, and Marshall's farm in 1890. (fn. 281)

As with much of western Gloucestershire, adoption of the new agricultural techniques of the 18th century was slow. The main change in practice was the replacement of the rye crop by wheat, made possible by the use of lime and other forms of manuring; (fn. 282) only 3 a. of land was returned as under rye in 1801. The crops returned then — 289 a. of wheat, 195 a. of barley, and 65 a. of other crops (including less than 5 a. of turnips and no clover or grass seeds) (fn. 283) — suggest that the traditional rotation of two crops and a fallow still obtained. By 1866 a more sophisticated rotation had been introduced, with the land mainly under wheat, barley, root crops, peas, and beans, and with vetches, clover, and grass-seeds also playing a part. The total land under crops returned in 1866 was 816 a. compared with 249 a. of permanent grass. The later years of the 19th century saw the usual decline in arable, mainly accounted for by a fall in the amount of wheat grown: by 1896 in the parish (as enlarged by the detached land of Pauntley in 1883) 620 a. was returned as under crops and 580 a. as permanent grassland. The number of cattle kept rose during that period, from 47 in 1866 to 116 in 1896, and sheep, with total flocks of 575 returned in 1896, remained a significant part of the local farming enterprise. (fn. 284)

In the parish (as enlarged) the pattern of c.15 principal farms of between 50 and 150 a. established by the mid 19th century continued during the 20th. At the sale of the manor estate in 1913 a number of the farms were bought by their tenants, (fn. 285) and in 1926 of the larger farms (over 50 a.) eight were owneroccupied and seven were tenanted; there were then nine smaller units. The farmers of the parish then employed a total of 39 workers full-time and another 24 on a casual basis. (fn. 286) There was little change in the pattern later in the century, apart from a rise in the amount of owner-occupied land and a trend for some of the smaller holdings to be worked on a parttime basis: in 1986 there were 13 farms of over 20 ha (c.50 a.) and eight smaller units and 46 people (including the farmers and their families) were employed on the land full-time and another 10 on a seasonal or casual basis. (fn. 287)

There was the usual recovery in the amount of arable in the mid and later years of the 20th century with 875 a. returned as under crops compared to 930 a. of permanent grassland in 1956, by which time sugar beet (83 a.) had become a significant cash crop. Livestock farming, particularly dairying, was, however, the dominant enterprise. In 1956 907 cattle were returned, including 215 cows described as in milk or calf for the dairy herds and 68 in milk or calf for the beef herds. In 1986, when 1,132 cattle were returned, the equivalent figures were 495 and 175; of the 15 main farms four then specialized in dairying, three were mainly engaged in dairying, and one reared beef cattle. Sheep raising was an expanding enterprise, with 238 breeding ewes returned in 1926, 473 in 1956, and 506 in 1986. Fruit growing also continued: 20 a. of orchard was returned in 1926 when the parish had at least one specialist fruit grower, and in 1986 26.6 ha (66 a.) of orchard produced cider and dessert apples and pears. Oxenhall shared with adjoining parts of Herefordshire and Gloucestershire in the expansion of the horticultural sector of farming during the 20th century. Soft fruit was grown commercially by the 1920s, and in 1986 29.1 ha (72 a.) was returned as under small fruit, vegetables, and nursery stock: two occupiers then specialized in fruit, one in vegetables, and one in general horticulture. (fn. 288) In the last years of the 20th century and the first of the 21st the dairy herds of the parish were given up. In 2006 most of the farms raised beef cattle and sheep and one farm supported a large flock of goats. (fn. 289) The parish then had several fruit farms, a nursery for young trees, and a small vineyard which had begun production in 1984. (fn. 290)

WOODLAND MANAGEMENT AND WOODLAND CRAFTS

All of Oxenhall's woodland was apparently open to rights of common by the tenants in the 14th century (fn. 291) but by the 17th all but a small part, the later Shaw common, was reserved in severalty to the lord of the manor. As mentioned above, parts were leased to tenants in the early 17th century, leading to the felling and clearing of some areas. (fn. 292) After the establishment of the furnace at Ellbridge, however, the bulk was used for coppicing for charcoal production, (fn. 293) a practice probably already followed in some parts of the woodland by 1608 when two 'colliers' lived in the parish. (fn. 294) Francis Finch, who by 1634 employed a woodward to preserve the woods on his manor from depredation by local cottagers and their animals, (fn. 295) cut and charcoaled large quantities of cordwood in Hay wood in the late 1630s. (fn. 296) In 1659 in the manor coppices, then extended at 240 a., the practice was to fell 20 a. at 12 years' growth each year, (fn. 297) and intensive use of the woods for charcoal continued under the Foleys during the late 17th and early 18th century. At the turn of the century the Oxenhall woods, with those belonging to the estate in Newent and Longhope, were managed on a perpetual cycle of cutting at 14 years' growth. (fn. 298) Some of the smaller groves attached to tenant farms were also used for the same purpose, and leases granted by the manor usually reserved all timber on the farms except for that traditionally allowed as 'bote' for the upkeep of buildings and hedgerows. (fn. 299) In 1670 Thomas Foley while on a visit to the manor encouraged his tenants to plant acorns on their lands. (fn. 300)

The large quantities of oak bark produced by Francis Finch's cording operations in the 1630s were sold to Gloucester city tanners, (fn. 301) and in the early 18th century the estate produced bark for tanneries in Newent and elsewhere, as well as wood for making hoops (for barrels), laths, and broomsticks. (fn. 302) A cooper occupied one of the cottages adjoining the woods in 1773, (fn. 303) and most of the cottagers living around Shaw common were probably supported in part by woodland crafts. Among them during the 19th century were woodcutters, lath makers, wood turners, hoop makers, a chair maker, and a hurdle maker. (fn. 304) The canal, which had a timber yard on its bank near Oxenhall pool in 1841, (fn. 305) aided the distribution of woodland products. In the late 19th century annual sales of timber and coppice wood were held by a local firm of auctioneers, and in 1913 most of the woodland was still managed as coppice, cut at 16 years' growth. (fn. 306) The sporting rights in the woods were exploited in the late 19th century under the Onslows, who employed several gamekeepers. (fn. 307) Those rights were valued at £100 a year in 1902, (fn. 308) and at the sale of the estate the woods were offered in a single lot as a sporting and agricultural estate; (fn. 309) but in the event the purchaser in 1914 sold them a few months later to the Crown, and in 1924 with the adjoining woodland (the whole known collectively as Dymock Woods) they were transferred to the Forestry Commission for commercial management. (fn. 310)

COAL MINING

The coal seams that underlie Oxenhall and the former detached land of Pauntley in a thin band running between Hillend, on the Dymock boundary on the north-east, and Kilcot, on the south-west, were worked sporadically during the 18th and 19th centuries. A field adjoining Peter's Farm, where old shafts were visible in the 1880s, (fn. 311) was known as Mine Pit field by 1729. (fn. 312) The main attempts to develop the coal deposits were associated with the building of the Hereford and Gloucester canal in the 1790s. During 1794 and 1795 the canal company sank shafts on the lands of Lower and Hill House farms in Pauntley, (fn. 313) and in 1796 it built a branch of the canal through Oxenhall to serve those mines. The company transferred its lease of the mining rights on the two farms to Richard Perkins, who formed a partnership with John Moggridge of Boyce Court, in Dymock. Perkins set up a steam engine and sank further shafts in 1796 and two years later purchased four of the canal company's barges, but the company became increasingly impatient with his slowness in supplying the coal they needed to burn bricks and lime for the work then continuing on the main line of the canal and Oxenhall tunnel. In 1799 it also complained that some of the coal he raised was being taken out by wagon and not by the canal. Perkins's mining operations came to an end soon after 1800. (fn. 314) The canal branch leading to the works was disused and leased in sections to adjoining farmers before 1841, (fn. 315) but the pits on Lower and Hill House farms were being worked again that year when the census recorded two miners occupying a cabin in the area and a coal merchant living in a cottage. (fn. 316)

A more substantial project was begun in the neighbouring part of Oxenhall in 1875, when the lord of the manor R.F. Onslow granted a lease of mining rights to William Aston. The following year Aston and investors from the industrial Midlands formed the Newent Colliery Co. and secured a wider lease covering a large part of Onslow's estate. The company opened a mine (Newent colliery) beside the lane south-east of White House Farm; in 1879 it was employing 60 workmen but the venture was unsuccessful and the company was wound up in 1880. (fn. 317) No serious attempts to exploit the coal in Oxenhall are recorded later, although a firm of investment brokers issued an optimistic prospectus soon after the sale of the Onslow estate in 1913. (fn. 318) In 2006 the overgrown shafts and waste tip of the 1870s colliery provided the main reminders of mining operations in Oxenhall.

MILLS

A corn mill belonging to Hill House farm stood on the brook below and just to the north of the farmhouse. (fn. 319) It was sold with the farm in 1596 to Sir Edward Winter (fn. 320) and was leased in 1609 to Thomas Hill. In 1639 Sir John Winter leased the watercourse running to the mill to Francis Finch, (fn. 321) evidently to facilitate water supply to the latter's Ellbridge furnace. The next owner of Hill House, John Brock, conveyed the mill in 1660 to John Spicer, (fn. 322) the manager of the furnace under Thomas Foley, and the following year he and Spicer renewed the lease of the watercourse to Foley. (fn. 323) Probably from that date the mill ceased working; it had been demolished by 1731. (fn. 324)

Further east, a mill on the Ell brook belonged to Crooke's farm. In 1645 the farm's owner, Edward Hooke, leased its leat to Francis Finch, with an undertaking that water from the brook would only be directed down it to the mill at times when Ellbridge furnace was not in blast. (fn. 325) Edward's son John renewed the lease to the Foleys on the same terms later in the century. (fn. 326) Crooke's Mill was recorded as a working corn mill in 1882 (fn. 327) and is thought to have ceased operation when Gloucester corporation built its waterworks a short way downstream in the 1890s. (fn. 328)

A mill called Ellbridge Mill, standing just upstream of the bridge of that name, was recorded from 1444. (fn. 329) In the early 17th century it formed part of Marshall's farm and in 1638 Edward Clarke leased it to Francis Finch, who converted it as part of his ironworks. In 1659, under Thomas Foley, the mill was used as a steelworks in connexion with the furnace. (fn. 330) It remained in use for that purpose in 1670, when there was a suggestion that it should be turned back to corn milling to make up a shortage of capacity in the area, (fn. 331) to which the abandonment (or partial abandonment) of the Hill House and Crooke's mills had evidently contributed.

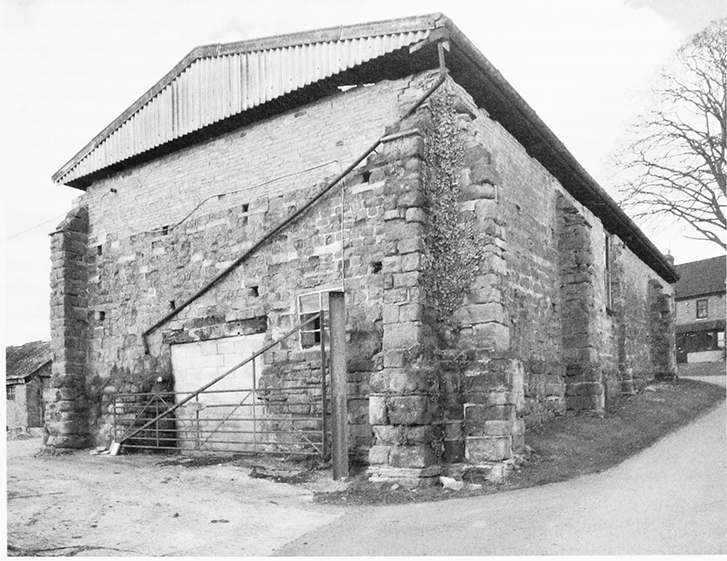

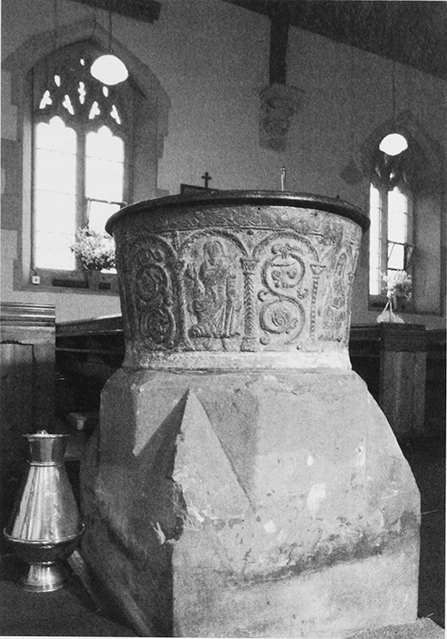

ELLBRIDGE FURNACE

The iron-smelting furnace at Ellbridge (often called Elmbridge furnace) was established by the lord of the manor Francis Finch before 1638. It was built on waste land between the Ell brook and the lane that became known as Furnace Lane, and, as mentioned above, the works incorporated the nearby Ellbridge mill. (fn. 332) In the late 1630s Finch bought cinders (the residue of ancient iron workings) from local landowners (fn. 333) and took leases to secure his supplies of water to power the bellows. (fn. 334) By 1655, partly by the purchase of coppice wood, he had incurred debts of £4,000 and in an attempt to recover his position he made an agreement with the Midland ironmaster Thomas Foley under which, in return for Foley standing security for his debts, he mortgaged the furnace and its sources of supply of cinders and charcoal to Thomas Lowbridge of Wilden (Worcs.), Foley's agent or partner. Finch was to continue to work the furnace but supply Lowbridge with pigiron to the value of the debts, the iron to be delivered to Ashleworth on the river Severn for shipping upstream to ironworks of Foley and his partners at Wilden and the adjoining Stour valley. Most of Finch's debts remained outstanding in October 1658 when the same three parties made a further agreement on similar lines, (fn. 335) but a few months later Finch sold Oxenhall manor with his residual rights in the furnace to Foley. (fn. 336)

Under Foley and his descendants the furnace was worked on an extensive scale, and the operation of powering and charging it employed resources from an area extending well beyond their manors of Oxenhall and Newent. The use of water from the Ell brook and its tributaries was secured by a series of leases and agreements with other landowners and Foley tenants holding lands bordering the streams. (fn. 337) Part of the supply came from a 5-a. pool in the valley east of the parish church. It was apparently constructed or enlarged by Francis Finch, (fn. 338) and he, or possibly Foley, built a long leat to bring water to the pool from Ell brook near Hill House Farm; the leat followed a course north of the brook similar to that taken later by the colliery branch of the Hereford and Gloucester canal. In addition the Foleys built three storage ponds on feeder streams of the Ell brook about 4 km distant from the furnace, on Gorsley common at the boundary of Newent and adjoining parishes. (fn. 339)

63. Building at the former Ellbridge ironworks