Pages 302-337

A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by Victoria County History Oxfordshire. All rights reserved.

In this section

ROTHERFIELD PEPPARD

Until 20th-century reorganization the ancient parish of Rotherfield Peppard stretched for 5½ miles (9 km) across Binfield hundred, from the Chiltern hills in the west to the Thames in the east. (fn. 1) Settlement is scattered, comprising isolated farmsteads and groups of houses set around commons or alongside roads. Formerly supporting a mostly poor farming population, from the 19th century the parish was subject to an ongoing process of gentrification.

Blount's Court, a minor residence of the Stonor family from the 15th to the early 18th century, lies in the far south of the parish, on the north-eastern edge of the 20th-century dormitory town of Sonning Common. (fn. 2) In the east, the southern suburbs of Henley-on-Thames extended into Rotherfield Peppard before the First World War. Nevertheless, although Henley lay only 3 miles (5 km) to the north-east of Peppard church, the town was probably eclipsed as a market centre by Reading, 5 miles (8 km) to the south, with which Peppard was connected by regular carrier and bus services from the 19th century. The suffix 'Peppard', from the chief medieval landowners, was added to the place name from the Middle Ages, distinguishing it from neighbouring Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 3)

Parish Boundaries

As with Greys and Harpsden, Peppard's elongated shape was probably the result of deliberate planning before the Norman Conquest, when an estate here was hived off from Benson. (fn. 4) In the 19th century the parish's (and county's) eastern boundary followed the river Thames for about 400 m., while the long northern boundary with Rotherfield Greys ran along roads and through fields as far as Greatbottom Wood. In the wooded north-west, the boundaries with Mongewell and Ipsden mostly followed paths and woodland boundaries; part of the western boundary with Checkendon followed similar features, but was largely undefined where it approached and looped around the former monastic grange of Wyfold. The boundary was also undefined in the wooded south-west, where the parish bordered Caversham and Sonning for short distances, and where it turned abruptly northwards into Shiplake. However, most of the Shiplake boundary followed the road from Kingwood Common to Blount's Court Farm. The long southern boundary with Harpsden, several sections of which were also undefined, passed mainly through fields on its way to the Thames. (fn. 5)

The antiquity of some of these boundaries is uncertain, particularly in the west where the area around Wyfold and Kingwood was shared in common by the inhabitants of Peppard, Harpsden, and Checkendon in the Middle Ages. (fn. 6) The boundary around Wyfold almost certainly post-dated the foundation of Thame abbey's grange in the 12th century, although it was probably established by 1452 when the rectors of Peppard and Checkendon each claimed the tithes of Wyfold manor. By then Wyfold was said to lie in Checkendon parish. (fn. 7)

In 1879 the ancient parish covered 2,194 acres. (fn. 8) In 1932 Peppard lost 186 a. to Henley parish and borough and 4 a. to Harpsden, but gained 2 a. from Rotherfield Greys, leaving it with 2,007 acres. Changes in 1952, involving Harpsden, Rotherfield Greys, Checkendon, Eye and Dunsden, and Shiplake, left it with 1,764 acres. Further minor changes to the boundaries with Checkendon and Sonning Common left it with 1,759 a. (712 ha.) in 2001. (fn. 9)

Landscape

The parish lies chiefly on chalk overlain by extensive patches of river gravel, except around Bolt's Cross in the north and Kingwood in the west where the high ground is capped by a mantle of clay-with-flints. (fn. 10) Chalk and gravel pits are scattered throughout the parish. (fn. 11) Close to the Thames, the alluvium of the floodplain (at 32 m.) provided a small area of meadow known as Peppard mead, which was developed for housing in the 20th century. (fn. 12) From there the ground rises to 75 m. at Highlands Farm and to 95 m. at Cowfields Farm, the church, and Blount's Court, rising still further to 110 m. at Bolt's Cross, 120 m. at Kingwood Common and Wyfold Grange, and 165 m. in the far north-west of the parish. (fn. 13) As elsewhere in the area the parish's dry valleys provided no water, and inhabitants relied on ponds and wells until the introduction of mains water, which was largely completed by 1926. (fn. 14)

As with Greys, the place name suggests that the extensive commons of the parish were already cleared of trees during the Anglo-Saxon period. (fn. 15) A medieval deer park probably lay between the church and Blount's Court, in the steep-sided valley of Stony Bottom. (fn. 16)

Communications

Roads

Two long-distance roads pass through the parish: the north–south road from Nettlebed to Reading, and an east–west route from Henley to Goring. (fn. 17) On entering the parish at Bolt's Cross, the north–south road (called Peppard Lane) leads southwards to Peppard Common. A pond opposite the Dog Inn was filled in when the road was straightened in the 1950s, and a mound opposite the Red Lion was removed to improve visibility. (fn. 18) The road bends sharply as it descends the hill on the south side of the common; part of an alternative route across the common was removed in the late 20th century. (fn. 19) The east–west road (no longer a major thoroughfare) was a continuation of Pack and Prime Lane (in Rotherfield Greys); the stretch east of Peppard Common was called Dog Lane, and in 2007 was mostly a narrow, unmetalled path. On meeting Peppard Lane, the road continues as Colliers Lane and Wyfold Lane, leaving the ancient parish at Wyfold Grange.

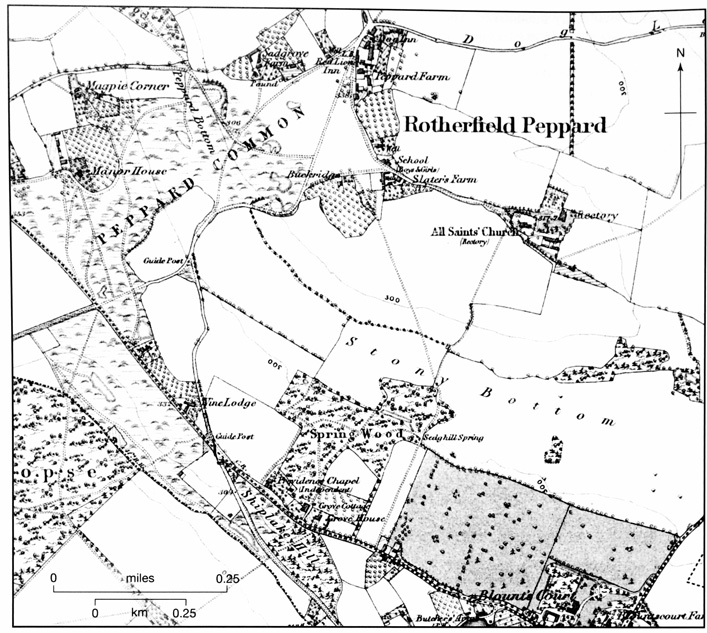

73. Rotherfield Peppard parish c. 1840, showing boundaries, land use and some later features.

Two other roads formed part of the parish's boundaries, suggesting that they were known in the early Middle Ages. The road from Stoke Row to Shiplake enters the parish at its north-western corner, and loosely follows the Checkendon boundary before crossing Kingwood Common. Beyond the common the road formed the ancient boundary with Shiplake as far as Blount's Court Farm. In the east of the parish Dog Lane joins the former Greys–Peppard boundary road to the Thames. Three short north–south roads cross the narrow eastern part of the parish, linking Mill Lane to an east–west road in Harpsden. One provides access to Gillotts, another leads from Henley to Harpsden, while the easternmost forms part of the former turnpike road from Henley to Reading. (fn. 20)

Numerous tracks and paths criss-cross the parish, particularly the two commons. Crosslanes (as its name suggests) lies at the intersection of a path from Peppard to Henley with one from Greysgreen Farm (in Rotherfield Greys) to King's Farm (in Harpsden). (fn. 21) Several paths also meet at Cowfields Farm, while others lead to Sedgehill spring, south of the church, an important source of water in the parish.

Carriers, Post, and Rail

Regular carriers to Reading passed through the parish from the mid 19th century, and in the early 20th two (later three) Peppard-based carriers operated a daily service. A motorised bus service from Stoke Row to Reading, which stopped at Peppard Common, was introduced by British Automobile Traction in 1919, and taken over by the Thames Valley Traction Company in 1920. A daily service was provided by 1924, when only two carriers survived. A single carrier, operating three days a week, was last mentioned in 1931. (fn. 22) In 2007 regular bus services connected Peppard to both Reading and Henley.

A sub-post office was recorded in 1847, run by Lucy Reeves, a baker, probably from a cottage on the corner of Church Lane. (fn. 23) In 1854 the parish clerk, James Crutchfield, took over the service, but it seems to have closed soon after. Until c. 1897 letters were received on foot from Henley, and the only provision within the parish was a wall box, presumably at Peppard Common, and pillar boxes at Kingwood Common and on the Greys–Peppard boundary road. (fn. 24) From c. 1897 a shop and sub-post office at Peppard Hill was run by Maria Bond; it transferred to Ernest Fry's grocer's shop on Stoke Row road (in Shiplake parish) c. 1903, the sub-post office closing in 1996. (fn. 25) A second sub-post office was opened at Kingwood Common c. 1911, near Maitland sanatorium; it transferred to a site near Colmore Farm in the 1950s, but returned to its original location soon afterwards and closed in the mid 1980s. (fn. 26)

The branch railway line from Twyford to Henley, opened in 1857, crossed the narrow eastern part of the parish. A pair of cottages was built next to the line on the southern side of Mill Lane, presumably for signalmen operating the level-crossing. James Drake, a 'gateman' for Great Western Railway, lived there in 1871. (fn. 27) A road bridge over the railway was built in the early 20th century. (fn. 28)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

Human occupation in the parish up to half a million years ago is attested by a large number of Palaeolithic artefacts, recovered from a gravel pit at Highlands Farm close to an ancient side-channel of the Thames. (fn. 29) Palaeolithic hand-axes have also been found elsewhere in the parish, including Kingwood Common, Peppard Common, and Gillotts. (fn. 30) Neolithic occupation is suggested by the discovery of worked tools near Crosslanes, by possible flint-axe production at Peppard Common, and by a chipped flint axe found at Wyfold. (fn. 31) Bronze-Age implements have been discovered close to Blount's Court, and a large barrow of the same era survives near Crosslanes, while a linear ditch has been identified in Spring Wood. (fn. 32) Roman settlement in the parish is not well evidenced beyond finds of coins and pottery scatters, but villas and pottery production sites are known close by. (fn. 33)

No archaeological evidence of Anglo-Saxon settlement has yet been found in the parish, though the creation of a substantial estate before 1066 suggests both an agrarian population and an estate centre, sited possibly near Peppard Common in the likely vicinity of the Peppards' medieval manor house. (fn. 34) Eleventh-century settlement was probably dispersed as later, though perhaps with a concentration of estate workers close to the putative manorial site.

Population from 1086

In 1086 there were 17 tenant households on Rotherfield Peppard manor, headed by 10 villani, 5 lower-status bordars, and 2 slaves; all probably lived within the bounds of the later parish. (fn. 35) Eight landholders were taxed in 1306, 10 in 1316, and 13 in 1327; each presumably represented a household, which may suggest that the parish's population was rising. (fn. 36) The Black Death almost certainly reduced numbers: in 1377 poll tax was paid by only 31 adults over 14, suggesting a total population of around 55–68. (fn. 37) Further depopulation occurred in the 15th century when the number of rent-paying tenants fell from more than 30 in 1401 to 19 in 1470. (fn. 38) Population apparently failed to recover in the early 16th century: only 26 taxpayers were listed in 1523, and 16 in 1543. (fn. 39) However, from the 1570s baptisms consistently outnumbered burials. (fn. 40) Fifty-two men swore the obligatory protestation oath in 1642, implying an adult population of 104; 23 houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662, and 94 adult inhabitants were noted in 1676. (fn. 41)

Average numbers of baptisms increased from the 1720s, but were matched by rising numbers of burials after 1740, and in the 1770s burials briefly exceeded baptisms. (fn. 42) Rectors reported between 35 and 50 houses in the parish during the 18th century, almost certainly an underestimate: in 1801, 70 houses were occupied by 73 families, a total of 317 inhabitants. (fn. 43) The population increased steadily to 439 in 1841, occupying 100 houses, before falling back in subsequent decades. The 19th-century population peaked in 1881 at 484 persons in 93 houses, after which it fell again, presumably as a result of agricultural depression.

In the 20th century, rising prosperity and extensive housing development led to an increase of population from 410 in 1901 to 882 in 1931, occupying 193 houses. Following successive boundary changes, in 1951 there were 1,155 persons in 288 households, increasing to 1,525 persons in 465 households in 1971. Thereafter the number of households continued to rise, reaching 577 in 2001, though the population fell to 1,473. (fn. 44)

Medieval Settlement

Medieval settlement was dispersed, most people living in the western part of the parish in hamlets on the edges of Peppard and Kingwood Commons; there has never been a village of Rotherfield Peppard. (fn. 45) At Peppard Common settlement probably grew up where the north–south road from Nettlebed to Reading crossed the east–west route from Henley to Goring. (fn. 46) The medieval church lay 400 m. east of the common, along a lane which seems not to have been built on until the 20th century. (fn. 47) On the common's south-eastern edge was the medieval park, close to the presumed location of the early manor house. (fn. 48) A late 13th-century charter, which may refer to settlement around the common, describes a group of houses and gardens, one of them beside the street end (le stretende), from which a way ran to the curia (or manorial site) of Rotherfield. (fn. 49) To the south of the park lay Blount's Court, probably built in the early 15th century by a prominent resident freeholder. (fn. 50)

In the west of the parish, the medieval hamlet of Wyfold, which presumably lay close to Wyfold Grange on the Peppard–Checkendon boundary, may have included part of Kingwood Common. Fourteen tenants named in 1279 held extensive common rights in Kingwood, where the lord, Thame abbey, appropriated 200 a. of royal demesne in the 13th century. About the same time one Andrew of Kingwood was recorded as a tenant of Benson manor, of which Wyfold formed part. (fn. 51)

A mill stood on the parish's narrow Thames frontage from the 11th to the 20th century. Further west, farmsteads were established at regular intervals among largely arable fields. Of these, Cowfields farm, recorded as Coufold in 1369, and Highlands farm, named as Hellelane in 1401, were almost certainly of medieval origin. (fn. 52)

Settlement 1600–1900

A settlement called 'the village of Pepper Green' in 1642 was probably the group of houses shown on 18th-century maps, at the crossroads of Peppard Lane and Dog Lane on Peppard Common's north-eastern edge. (fn. 53) Although some 600 m. from the church this was probably also the hamlet called Peppard Green by the rector in 1814, which he described as comprising '12 families contiguous to the church'. (fn. 54) In 1840 the hamlet contained 10 houses on both sides of the apex of the triangular-shaped common; among them were Peppard and Sadgrove Farms and two public houses, the Dog and the Red Lion (known briefly as the Anchor at the end of the 18th century). To the south-east, where Church Lane forked on entering the common, lay four more houses including Slater's Farm, while on the common's north-western edge at Peppard Hill was another group of six houses, including Peppard House and Manor House (formerly a public house called The Blue Monkey), which appear to have encroached on former common land. (fn. 55)

The number of houses and inhabitants in the parish barely changed between 1840 and 1900 and there was little new building around Peppard Common. (fn. 56) Exceptions included the Unicorn public house at a crossroads at Peppard Hill, first recorded in 1853, and the National school, opened in 1871 on former common land at the west end of Church Lane. (fn. 57)

Unlicensed inclosure and building of cottages on the edge of Kingwood Common was reported in 1779 and marked on 18th-century maps. (fn. 58) In 1808 the rector described Kingwood as a hamlet about a mile from the church consisting of 20 houses. (fn. 59) The main focus of settlement was a group of inclosures in the southern part of the common, where 15 houses were recorded in 1840. Seventeen more houses were scattered around the common, including small groups of eight on the common's north-western edge and four (including Colmore Farm) on its south-eastern edge. (fn. 60) Little development occurred before 1900, apart from the temporary appearance of tents (occupied by tinkers and hawkers) in 1871–81. (fn. 61)

74. Rotherfield Peppard and Peppard Common c. 1883. Buildings lie scattered around the common in characteristically dispersed fashion, separated from the parish's principal residence at Blount's Court by the site of a medieval deer park in Stony Bottom and Spring Wood. The so-called Manor House was not of medieval origin.

In 1840 about a dozen houses were scattered at irregular intervals along the Stoke Row to Shiplake road, mostly to the south-east of Peppard Common. Apart from Blount's Court and the neighbouring farmstead, these were probably all of 18th-century origin or later; they included the Nonconformist chapel and manse, and a gentleman's residence called Vine Lodge. (fn. 62) More houses and a mission hall were built along the road on former arable land in the late 19th century. (fn. 63)

Settlement in the 20th Century

Extensive housing development occurred throughout the parish in the 20th century, principally around the commons, along the main roads, and to the south of Henley. A number of commercial premises were also built, as well as schools, farms, and two hospitals. (fn. 64) Nevertheless, in 2007 the parish's settlement pattern remained dispersed, mostly rural, and relatively remote from the area's major roads and urban centres.

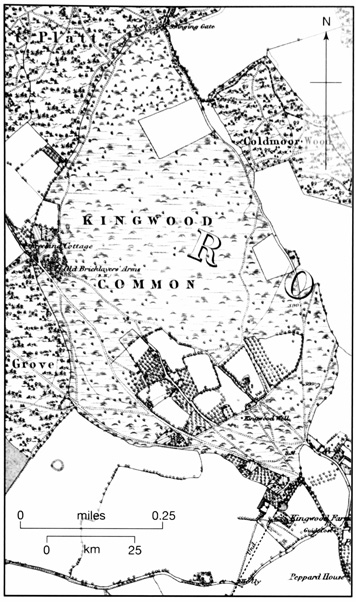

75. Kingwood Common c. 1883, already partly inclosed.

Peppard Common

As the number of wealthy residents increased before the First World War, vacant plots around Peppard Common were infilled and former arable inclosures developed, though the settlement pattern remained characteristically dispersed. (fn. 65) Development was less intense during the inter-war years, being mostly limited to scattered private houses, and a row of six council houses along Church Lane, the focus of post-war building activity. (fn. 66) Plots to the north of Church Lane were offered for sale in 1927 and again in 1938, but were not developed until the 1940s and later, including a further row of six council houses and two culs-de-sac. (fn. 67) Development of greenfield sites and infilling of existing plots continued into the 1970s, and though activity slowed thereafter, one result of the expansion was a new focus of settlement between Peppard Common and the parish church. (fn. 68)

A secondary school was built on Peppard Lane north of the common in 1932, but closed in 1962 and was later converted to a private house. Subsequent development of surrounding land included the creation (on the opposite side of the road) of a trading estate called Manor Farm. Nevertheless, in 2007 much of Peppard Lane between the common and the houses at Bolt's Cross (mostly built before 1800) remained open. (fn. 69) To the south-east of the common, some infilling took place along the Stoke Row to Shiplake road (including a former builders' yard converted to housing in 2002), but most development occurred on the road's opposite side, on land formerly in Shiplake parish but included since 1952 in Rotherfield Peppard. (fn. 70)

Kingwood Common

The early 20th century saw the foundation and rapid expansion of a sanatorium (later the Peppard Chest Hospital) on Kingwood Common's southern edge. (fn. 71) Less intensive development occurred around the same time on the common's eastern side, with the appearance (in former arable inclosures) of several large houses, including Cherry Croft and Great David's (both built 1912). (fn. 72)

During the Second World War a Royal Artillery camp and American military hospital were built in the north-western part of the common, close to the late 19th-century public house the Bricklayers' Arms (converted to a private residence in the early 21st century). In the early 1950s 72 huts at the former camp were used as housing by Henley Rural District Council. A controversial proposal by the council to build a housing estate on the site was defeated in 1956. Some of the buildings were still marked on a map of 1960 but were subsequently demolished. (fn. 73) After the war further housing development took place in the main group of inclosures in the south of the common, provoking local concern, while at the end of the 20th century houses were built on the site of the former sanatorium (closed in 1980). Despite the rise in house numbers, however, in 2007 much of Kingwood Common retained a remote and secluded character. (fn. 74)

The east of the parish

Considerable development occurred to the south of Newtown (in Rotherfield Greys), now part of Henley. The Henley and District War Memorial Hospital opened in 1923 on the corner of Mill Lane and the Henley–Harpsden road. A little earlier, large houses were built in Harpsden Heights along Mill Lane and a new parallel road to the south (Rotherfield Road), while land near the railway, belonging to George Shorland, was developed with houses, a motor garage and filling station. Houses were also built in the early 20th century on former meadow near the Thames. (fn. 75) Redevelopment followed the hospital's closure in 1984, and in the late 20th century some house plots were subdivided. The former Shorland properties were absorbed into an extended Newtown industrial estate. (fn. 76)

The Built Character

Rotherfield Peppard's buildings are similar in character to those of its neighbours. Although individual houses vary greatly in size and style, most are of brick and clay tile, with occasional use of timber-framing, flint, and slate tile. Since the 19th century thatch has rarely been used to roof either houses or outbuildings. (fn. 77)

Except for the parish church and Blount's Court, surviving buildings are all post-medieval. Some of the farmhouses (notably Cowfields and Highlands) may have replaced medieval predecessors, but the present buildings date from the 16th century and later. (fn. 78) The rectory house, too, probably occupies its medieval site, although it was first recorded in 1562 (in a state of dilapidation), and its present exterior is mid 19th-century. (fn. 79) A few 16th or 17th-century cottages survive, among them the Old Cottage on Colmore Lane, which was probably built as a hall house in the early to mid 16th century. The house is timber-framed with plastered wattle-and-daub infill and a plain tile roof, and has two bays and one storey with an attic, with a rear and a side outshut. (fn. 80) Most of the present housing stock, however, is 18th-century and later.

During the 19th century the number of houses rose from 75 to only 100 or so, and as several were often uninhabited demand for housing was presumably low. (fn. 81) There was some speculative building before the First World War, notably along the Stoke Row to Shiplake road, where the builder Charles Butler owned a number of houses. (fn. 82) However, in 1914 the parish council called for more cottages to be built for local labourers and artisans, and in 1919 gave the names of 14 applicants for houses to Henley Rural District Council. That year the council agreed to build 18 houses in the parish, although only six were eventually built, along Church Lane in 1928; (fn. 83) a further six (adjoining the first) were built after the Second World War. More important was 20th-century private development, which was chiefly responsible for the steady increase in the number of dwellings to 633 in 2001. (fn. 84)

Manors and Estates

Rotherfield Peppard was one of several 5-hide estates in the Henley area which were probably detached from the royal manor of Benson before the Norman Conquest. (fn. 85) From the 11th to the 20th century it was held by a series of high-status lords including the Pipards, Butlers, Stonors, and Flemings; the Pipards maintained a manor house and nearby deer park, but they and their successors were mostly non-resident. (fn. 86) From the 16th century to the early 18th some younger members of the Stonor family lived at Blount's Court, a house built probably in the early 15th century by the owner of a short-lived sub-manor. (fn. 87)

Nineteenth-century perambulations imply that the manor originally encompassed the entire parish. The Stonors sold off nearly all of the estate in the 17th century, however, and in 1840 held only 192 a., mostly as a single block in the north-west. The remains were finally sold in 1894. Other large estates in 1840 were also relatively compact, including (in the south-west) 245 a. belonging to the Wyfold estate, in the centre 220 a. held by Charles Elsee of New Mills and 212 a. by Mary Atkyns Wright of Crowsley Park, and in the east 432 a. held by the Hodges family of Bolney and 158 a. by the Halls of Harpsden. These estates were largely broken up during the 19th and 20th centuries. (fn. 88)

Rotherfield Peppard Manor

Descent to 1465

In 1066 Rotherfield Peppard was held freely by Uluric, and in 1086 by Miles Crispin of the king. (fn. 89) The manor formed part of the honor of Wallingford, which escheated to the Crown in 1300 and later became the honor of Ewelme. (fn. 90) Its overlords were therefore the holders of the honor, and men from Rotherfield Peppard attended the honor's frankpledge courts from the Middle Ages to the 19th century. (fn. 91)

Miles Crispin probably granted Rotherfield Peppard to his steward Gilbert Pipard, whom he sent to make a donation of land to the monks of Abingdon in 1107. (fn. 92) Gilbert's successor William Pipard, probably his son or grandson, held six fees of the honor of Wallingford in the mid 12th century, of which Rotherfield Peppard was one. (fn. 93) William was succeeded by his sons Gilbert (d. 1191–2), who died on crusade, and William (d. 1195). (fn. 94) William's successors were probably his sons Walter (d. 1214) and Roger (d. 1225), who inherited lands in Ireland from his uncle. (fn. 95) Roger's son William Pipard died in 1227, leaving his daughter Alice, a minor, as heiress. Alice became the ward of Ralph FitzNicholas, who before 1242 married her to his younger son Ralph. (fn. 96) Their son Ralph Pipard, 1st Lord Pipard, inherited the manor about 1265 and died in 1303. (fn. 97) His successors were his grandson John, a minor, who died in 1306, and his younger son John (d. 1331), who granted the reversion of his English lands after his death to his brother-in-law, Edmund Butler. (fn. 98)

Edmund Butler, twice Justiciar of Ireland, died in 1321, and was succeeded by his son James, the future earl of Ormond, but then a minor. (fn. 99) James (d. 1338) left as heir his second son James (II), aged seven, who received his father's estates in 1347; (fn. 100) meanwhile his mother Eleanor married Thomas de Dagworth, who held the manor in 1346. (fn. 101) James Butler (II) died in 1382 and was succeeded by his son James (III). (fn. 102)

In 1391 James conveyed the manor to John Waryn, Thomas Clobber of Henley, and William Blike, presumably as trustees in connection with his purchase of Kilkenny Castle. (fn. 103) The manor was then briefly divided. One half was held by William Faukener on his death in 1412, and passed to William his son; (fn. 104) the other half was acquired by John Drayton, possibly the man of that name (d. 1417) commemorated in the abbey church at Dorchester. (fn. 105) Both Faukener and Drayton received cash payments from the manor between 1398–9 and 1408–9. (fn. 106)

Descent from 1465

The two parts of the manor, together with the former sub-manor of Kents (below), seem to have been reunited in the possession of Richard Drayton of Dorchester, presumably a descendant of John Drayton. Richard sold the manor to his stepson Thomas Stonor in 1465. (fn. 107) The manor, known thereafter as Rotherfield Peppard or Blount's Court (from the former chief house of Kents manor), descended in the Stonor family until the sale of 1894, although not always in the direct male line. (fn. 108) Thomas Stonor (d. 1474) left the manor in his will to his second son Thomas (d. 1512), whose eldest son Walter (d. 1550) lived at Blount's Court before inheriting Stonor in 1536. (fn. 109) In the 17th century Blount's Court was again occupied by younger members of the family, of whom the last was Henry Stonor (1633–1705). On his death the house and some of its land were sold. (fn. 110)

In 1894 the Stonors sold Rotherfield Peppard, as part of their larger Nettlebed estate, to H.H. Gardiner, a London businessman who was forced to sell following financial losses. (fn. 111) Robert Fleming (1845–1933), a Scottish financier, bought the estate in 1903, (fn. 112) but sold the outlying parts in 1913, when the lordship of Rotherfield Peppard was divided. Manorial rights over Peppard Common became attached to Sadgrove (later called Manor) farm, while those over Kingwood Common were said to go with Colmore farm; (fn. 113) Fleming seems nonetheless to have retained the rights over Kingwood, and was called lord of the manor of Kingwood in 1920–31. The lord of Peppard manor was then Walter Ford of Dunsden, presumably as successor to George Ford, the tenant of Sadgrove farm in 1913. (fn. 114) Fleming was succeeded by his son Philip, who, in the late 1930s, gifted the entire Nettlebed estate (then 2,000 a.) to his nephew (Robert) Peter Fleming (d. 1971), in whose family it remains. Fleming was still called lord of the manor in the 1950s. (fn. 115)

Kents Manor and Blount's Court

A sub-manor called Kents was created in the 13th century. In 1286 Ralph Pipard granted John of Kent and Emma his wife an annual rent of 1 mark which Roger Stormy paid for land called la Selgrave in Rotherfield Peppard. (fn. 116) Three years later Kent was given free pannage in Pipard's wood and free grinding at his mill, and at about the same time Ralph sold him a house and curtilage, possibly near Peppard Common. (fn. 117) In 1319 John's descendant Robert of Kent held a house, (fn. 115) yardlands, 3½ a. of meadow, 10s. rent, pannage in the lord's wood, common in Kingwood, and a way extending from the house to Selegrovelond, all of which he sold to Roger de Shire. (fn. 118) Roger, in turn, sold the property to John de Alveton in 1321, a transaction which Robert of Kent confirmed. (fn. 119)

John de Alveton (d. 1361), the earl of Ormond's attorney-general, acquired other lands in the parish between 1323 and 1340, which on his death passed to his stepson Thomas Blount. (fn. 120) Blount (d. 1407) was first recorded in Rotherfield Peppard in the early 1360s holding his stepfather's estate. (fn. 121) In 1396 he leased to John Chiltern a house called Benschefysplace and land called Seyntfeyslond or Groveslond. (fn. 122) In 1401 Blount held a court and land at Hellelane (an early spelling of Highlands) for a nominal rent of 1d. each; Groveslond was still held by John Chiltern. (fn. 123) Thomas was succeeded by his son John Blount, the last member of the family, who was described as lord of Rotherfield Peppard (presumably meaning Kents) in 1412. (fn. 124) In 1425 the whole manor of Kents, with land in Rotherfield Peppard, Kingwood, and several surrounding parishes, was held by John Chiltern, before its re-absorption into the main Rotherfield Peppard manor before 1465. (fn. 125)

Blount's Court

Blount's Court, which lies on the southern edge of the parish along the Stoke Row to Shiplake road, was built probably by John Blount or his successors in the early 15th century. (fn. 126) The house was acquired with the rest of Kents and Rotherfield Peppard manors by Thomas Stonor in 1465, and became a minor residence of the Stonor family until its sale c. 1705; (fn. 127) Charles Price acquired it c. 1722, (fn. 128) and in 1803 the estate passed to his cousin Thomas Ovey, whose son sold it in 1821 to Charles Elsee of New Mills. Elsee sold it to John Bayley in 1828, repurchased it in 1836, and held 220 a. in the parish in 1840, (fn. 129) before auctioning the estate in 1841. The purchaser was Sir William Thomas Knollys (1797–1883), a descendant of the Knollys family of Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 130) Thereafter the estate was gradually dispersed, culminating in the sale of Blount's Court house in 1933. In 1960 the house was converted into company laboratories and offices. (fn. 131)

The conversion removed or obscured many earlier features, but an internal 15th-century stone doorway and some 16th-century panelling have been identified. (fn. 132) On Henry Stonor's death in 1624 the house included a hall, two parlours, nine chambers, two closets, and a lobby; service areas included a kitchen, two pantries, a larder and milkhouse, a bakehouse, a brewhouse, a stable, and three service chambers, including the maid's chamber. (fn. 133)

Probably in the 18th century the house was refronted in stone by the Price family, and was given a Doric porch and a semicircular bay window (Fig. 76). (fn. 134) The main front (including the porch) faces eastwards across the lawn, while the bay window looks north towards Stony Bottom. A southern wing, facing Blount's Court Road, adjoins the main part of the house at right angles. (fn. 135) When auctioned in 1841 the mansion included a stone hall and staircase, two parlours, a library, a drawing room, a boudoir, 11 bedrooms, two dressing rooms, closets and water closets; the service part included a servants' hall, a butler's pantry, a man's bedroom, bachelors' bedrooms, a housekeeper's room, a kitchen, a larder, and extensive cellars. Outbuildings included an ornamental dairy and scullery, a coach-house, a stable, and three servants' rooms. (fn. 136)

76. Blount's Court c. 1862, from the north-east. The exterior reflects remodelling probably by the Price family in the 18th century, but remains of the late-medieval house have been identified inside.

When the house was sold in 1960 it was described as a 'fine Georgian residence ... solidly built of stone and part in brick with slated roof with four urn vase surmounts', and included a hall, four reception rooms, domestic offices, two suites of bedrooms each with bathroom, five secondary bedrooms with two bathrooms, two servants' bedrooms, three small flats, and an 'old world gardener's cottage'. (fn. 137) In the late 20th century the original house was retained but was greatly extended westwards with offices and laboratories over the former shrubbery. (fn. 138)

A separate farmhouse at Blount's Court was also owned by the Stonors until 1705, and descended thereafter with the main house, whose owners let it to tenant farmers. Brick-built with a plain tile roof, the house has a 16th-century core; its 18th-century front was added probably by the Price family, while 19th-century alterations may have been by Knollys. Outbuildings include an early 18th-century barn. (fn. 139)

Other Estates

Two neighbouring estates contained land in the parish in the Middle Ages. In the west, Thame abbey acquired 200 a. of royal demesne in Kingwood in the 13th century, which became attached to its manor of Wyfold (held of the royal manor of Benson). (fn. 140) In the 19th and 20th centuries the Wyfold estate still extended into Rotherfield Peppard, although most of it lay in the neighbouring parish of Checkendon. (fn. 141) The medieval manor of Harpsden extended into Peppard's east part, where the Hall family of Harpsden Court held 158 a. in 1840. The Halls sold it in 1851. (fn. 142)

Several new estates were created in the late 17th century when the Stonors sold most of the manor, probably to pay recusancy fines. (fn. 143) In 1684, for example, John Stonor sold Highlands farm to Robert Hanson, a maltster of Blewbury near Didcot (formerly Berks.). (fn. 144) Hanson's son John sold the farm in 1719 to Samuel Grice of Henley, whose grandson George Blount sold it in 1754 to Anthony Hodges of Bolney Court in Harpsden. By then the estate included the neighbouring properties of Cowfields farm and Gillotts, which had also formerly belonged to the Stonors. (fn. 145) The Hodges family remained owners of the 432-a. estate in 1840, (fn. 146) and c. 1855 it was evidently sold to Edward Mackenzie of Fawley Court. Most was auctioned by Keith Ronald Mackenzie in 1906 and broken up, and Gillotts was sold c. 1920. (fn. 147)

Samuel Norman, whose family had been tenants of Rotherfield Greys manor, held land close to the Peppard–Greys boundary in the late 18th century. (fn. 148) Mary Atkyns Wright held the 212-a. estate in 1840, adjoining her lands in Rotherfield Greys. Known as Peppard farm, it formed part of the Crowsley Park estate sold to Henry Baskerville in 1844, and was auctioned as part of the Mackenzie estate in 1906. (fn. 149) The farm, with neighbouring Greysgreen farm in Rotherfield Greys, was owned by Mrs Pipe Wolferstan in the 1930s, who by this date was described as the principal landowner in the parish. (fn. 150)

Wallingford priory held lands and rents in Rotherfield Peppard and Newnham Murren, worth £1 10s. in 1291. (fn. 151) Goring priory held land at Colmore of Peppard manor until the Dissolution. (fn. 152) The glebe, about 56 a. from the 17th to early 20th century, lay in the centre of the parish, surrounding the church and rectory. (fn. 153)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century inhabitants depended largely on agriculture, and numerous farms were dispersed throughout the parish's settlements and fields. From the Middle Ages a variety of rural trades and crafts were practised, and in the 19th century there was a significant paper manufactory and flour mill by the Thames. Some long-standing businesses were established at that time, notably the Butler family's building firm, while in the 20th century some specialized employment in medicine and technology was created at Peppard Chest Hospital and Blount's Court. The parish's sub post-offices closed in the late 20th century, but in 2007 a few shops and several business parks continued.

The Agricultural Landscape

Peppard's landscape was similar to that of Rotherfield Greys, and its inhabitants had access to a similar range of agricultural resources. (fn. 154) Domesday Book suggests that the mixed countryside and mixed farming of later periods was well established by the 11th century: in 1086 Miles Crispin's 5-hide manor had land for 7 ploughteams, 9 a. of meadow, and woodland ½ league long and 3 furlongs broad. (fn. 155)

Fields, Crofts, and Arable

In the Middle Ages there were presumably irregular open fields in Rotherfield Peppard as in other parts of the south-west Chilterns, but little is known of their location or extent. (fn. 156) Occasional references to tenants' yardlands between the 14th and 17th centuries suggest that some land was farmed in common, and in the 1660s several copyholders on the Stonor estate held yardlands of 40 acres. But the same sources also reveal numerous crofts inclosed by hedges, while there is no mention of the bylaws and field orders typical of open-field farming. (fn. 157) As early as 1279 tenants' land at Wyfold (on the Peppard–Checkendon boundary) was mostly described in terms of crofts and groves. (fn. 158) Most likely the parish was largely inclosed by the end of the 16th century, (fn. 159) and in the 1620s the Stonors' demesne was divided among numerous closes. A landscape of hedged inclosures was also depicted in the 18th century. (fn. 160)

Arable land was almost certainly scattered throughout the parish from an early date. The tenants at Wyfold presumably grew grain in their crofts in the late 13th century, while in the 1660s arable was recorded near Kingwood Common as well as in the centre and east of the parish. That pattern persisted in 1840, when more than two thirds of the available land was ploughed. (fn. 161)

Woodland, Commons, Parks, and Pasture

From the Middle Ages woodland dominated the north-western parts of the parish. In 1263 an agreement between the monks of Thame and the lords of Rotherfield Peppard and Harpsden allowed common grazing in 300 a. of wood extending from Coldmoor wood on the north-eastern side of Kingwood Common across the boundary into Checkendon. (fn. 162) The extent of tree cover must have varied over time according to levels of grazing, the management of coppices for timber and underwood, and demand for arable. Numerous inclosures were carved out of the wood, including that which Francis Gouldar 'turned into arable by grubbing up bushes, ferns, briers, hazel stubs and such like from the waste' in about 1590. (fn. 163) In the 1670s tenants' right to cut wood for household use in Kingwood was limited to two loads each, while in the 1770s unlicensed cottages and inclosures encroached on the common. (fn. 164) In the late 18th century Kingwood appears to have been an open area of heath and grass, and remained so until the second half of the 20th century when a decline of grazing allowed woodland to regenerate. (fn. 165) Further east, smaller patches of woodland were mapped in the 18th and 19th centuries, again varying in extent over time, but such that in 1840 most of the large landowners held at least some wood. During the 20th century individual woods were grubbed up, but across the parish as a whole the area of woodland increased. (fn. 166)

Ralph Pipard was granted free warren at Rotherfield in 1284 and held an inclosed park on his death in 1303. Probably it lay on the south-eastern side of Peppard Common, where later sources recorded arable closes called 'Great Park' and 'Little Park', and wood called 'Park Wood' (in all about 60 acres). (fn. 167) The park appears to have been maintained throughout the 14th and 15th centuries. In 1355 the park-keeper was given 10s. by the Black Prince, presumably after a successful hunting expedition, while tenants whose animals trespassed in the park were brought before the manorial court in the 1360s. Labourers were hired in 1406–7 to repair the park's boundaries. (fn. 168) In 1517 Thomas Stonor enlarged the park by inclosing 38 a. formerly occupied by tenants; this may have been land surrounding the house at Blount's Court, of which 32 a. was called parkland in 1840. (fn. 169) In the 17th century part of the original park was converted to arable, and the process evidently continued, so that only about 14 a. of 'Park Wood' (later called Spring Wood) survived in 1840. (fn. 170)

Private pasture held by the lord of the manor was broken into in 1351, and arable closes must regularly have been put down to grass to replenish the soil, as on the Blount's Court estate in the 19th century. (fn. 171) Such closes may have been used to supplement the extensive but poor-quality common grazing available in the woods and commons in the west of the parish. An agreement in 1211 between Walter Pipard and Thame abbey allowed the tenants of Rotherfield to pasture their animals and collect wood for fuel and repairs over a wide area around Wyfold Grange, rights which were reinforced in 1263 when pannage was recorded. (fn. 172) Both lord and tenants were concerned to protect the manor's common pasture from outsiders, as in 1456 when a Caversham man was fined for pasturing sheep in the parish. (fn. 173)

The right of common grazing on Peppard Common (54 a. in 1840) and Kingwood Common (140 a.) persisted into the 20th century. In 1906 occupiers of cottages in the parish were entitled to take undergrowth and scrub for fuel and litter, and to graze up to 50 cattle, sheep, and donkeys. When the commons were registered in 1965 no-one came forward to claim common rights, although some inhabitants continued to graze cattle and gather wood. (fn. 174)

Meadows

Lack of water meant that meadow in Rotherfield Peppard was largely confined to the narrow Thames frontage in the extreme east of the parish. Only 9 a. belonged to the manor in 1086 and 4 a. 'that can be mowed' in 1303. (fn. 175) In the early 15th century a watercourse was mended 'from the lord's ditch to the lord's meadow', but this was not necessarily privately inclosed. In the same period the lord regularly leased 6 a. 'lying in the common meadow', together with 1 a. called Shabbydacre which belonged to the mill. (fn. 176) Some medieval tenants held small pieces of meadow, such as Robert Wheeler who occupied a house, ½ yardland, and ½ a. of meadow in 1457. In 1465 a miller was fined for allowing his horses to graze in the lord's meadow. (fn. 177)

Three closes of meadow, called Peppard mead, Mill mead, and Mill close, were recorded in 1840, divided into nine pieces and amounting to about 11 acres. The area was probably larger in the Middle Ages before part of the river-bank was built on, and in the 20th century the whole of the former meadow was developed for housing. (fn. 178)

Medieval Agriculture

Medieval Demesne Farming

Two hides (around 240 a.) of land were in demesne in 1086, worked by two slaves with two ploughteams. By 1303 and 1338 the demesne was only 60 a., perhaps reflecting the Pipards' and Butlers' non-residence and their lengthy absences in Ireland. (fn. 179) The land may have been directly managed c. 1300 when tenant labour-services were available to reap and carry crops, but by 1338 these had been commuted, and by the end of the century the demesne was leased. In 1398–9 John White paid 3s. 4d. for the 'buildings and close of the manor of Rotherfield', while others leased arable fields, the park, meadows, mill, and fishery. However, tenants' rents were collected by a reeve and delivered to the manorial lords, William Faukener and John Drayton, who retained control over the manor's woodland and court, and were responsible for the maintenance of some manorial buildings. Their successors, Thomas Stonor, father and son, appear to have followed the same policy in the late 15th century, leasing the land but collecting the rents. (fn. 180)

Although the Pipards and their successors almost certainly practised mixed farming, little is known about their demesne management. A low valuation of 2d. an acre in 1303 and 3d. in 1338 suggests that the arable was not farmed intensively and may not have been kept in good heart. Presumably any surpluses were sold at Henley, which was also the most likely destination for the manor's woodland produce – the woodland was not leased in the Middle Ages, suggesting that it was regarded as a valuable resource. Pannage (money for grazing pigs in woodland in autumn) was regularly collected in the 14th century. Trespassers in the manor's woods were prosecuted, as when four young oaks were felled without licence in 1366. Other trees felled included beech and ash. In the early 15th century various woodland products were sold or used on the manor, including timber for repair of the mill, loppings, talwood (which may have been shipped to London for use as fuel), and charcoal. The demand for wood tempted a manorial tenant to fell oaks and cart them to Henley, for which he was fined in the manor court in 1461. (fn. 181)

Medieval Tenants and Farming

In 1086 there was land for 7 ploughs, although only 5 ploughteams were recorded: 2 on the demesne and 3 shared by 15 tenants (10 villani and 5 bordars). Nevertheless, the estate's value had increased from £7 in 1066 to £10 in 1086. (fn. 182) There was apparently little growth in the number of customary tenants during the 12th and 13th centuries: their annual rents were worth only £2 7s. 10d. in 1303, while those of the cottars amounted to £1 4d. By contrast, free tenants paid a total of £17 2s. 1d., their appearance perhaps indicating that settlement in the parish was spread by the inclosure and cultivation of common land. (fn. 183)

In 1341 it was claimed that all but three carucates (about 360 a.) lay uncultivated on account of the poverty of the parishioners, which may be reflected in the low tax assessment of 1334 and a decline in free tenants' rents in 1338. Probably that was a result of the early 14th-century agrarian crises, which also affected other parts of the Chilterns. (fn. 184) In the 1350s and 1360s both customary and free tenants occupied a variety of holdings: cottages and crofts, and land measured in acres and yardlands, some for life, others at the lord's will or for a term of years. In the aftermath of the Black Death some holdings remained vacant, and a few buildings fell into ruin, but a number of tenants also took the opportunity to accumulate land. In 1358, for example, John de Alveton held at least five formerly separate holdings, amounting to 4¼ yardlands. (fn. 185)

The number of tenants may have continued to fall during the 15th century. In 1470 only 19 tenants paid rents compared with more than 30 in 1401. Rents were also reduced, indicating a falling demand for land, as allowances to the reeve in the early 15th century make clear. (fn. 186) At courts in the 1450s and 1460s tenants were frequently chastised for not repairing ruined buildings, among them Joan Taylor, whose walls and plasterwork needed attention, while in another house the timber and roof were decayed. But although some holdings lay vacant, and individual buildings were destroyed, free and customary tenants continued to hold land of the manor, and there is little to suggest that the pattern of settlement was radically altered. (fn. 187)

Tenant agriculture probably resembled the mixed farming of the lords. In the mid 14th century tenants grew grain, including dredge and probably barley (which they brewed into ale). Neighbours' animals sometimes strayed into their crops, amongst them horses, oxen, cattle, sheep, and pigs, of which some tenants held large numbers: in 1364 both John Chapman and John Cowherd were fined for allowing flocks of 160 sheep to graze illegally. A few tenants may have supplemented their diet by poaching, especially rabbits in the lord's warren. (fn. 188)

The names of many tenant holdings were recorded in 1401, though most individual farms cannot be identified. A probable exception is Hellelane, an early spelling of Highlands, a farm in the east of the parish. Similarly, lands called Coufold in 1369 almost certainly formed part of the later Cowfields farm. (fn. 189)

Farming From 1500 to 1800

Estate Management

Apart from their enlargement of the deer park in 1517, (fn. 190) little is known about the Stonors' management of the manor in the 16th century. Presumably the estate was leased as in the early 17th century, when the family employed a bailiff, John Benwell, to oversee the leasing of the demesne (then about 300 a.) and to manage the woods. (fn. 191) A survey of the 1660s records the lease of 322 a. of demesne, 68 a. of leasehold land, and 234 a. of copyhold land, although 331 a. of woodland was kept in hand. All those lands extended into the neighbouring parishes of Harpsden and Shiplake; within Peppard itself the demesne extended as far east as Gillotts, but was concentrated in the south of the parish near Blount's Court. The demesne brought in over £109 a year in rents, but the leasehold and copyhold lands less than £10, despite a valuation of £142. (fn. 192)

The survey was made shortly after the Stonors recovered control over the manor in 1660, following an eight-year lease forced upon them by the Cromwellian government's demand for recusancy fines; possibly it was made in preparation for a subsequent lease. (fn. 193) In 1662 the lessees held an estimated 250 a. of arable, 30 a. of meadow, 30 a. of pasture, 200 a. of wood, and 100 a. of furze and heath, together with houses, cottages, gardens, orchards, a dovecot, and three watermills. (fn. 194) In the 1670s Thomas Stonor began to improve the soil around Blount's Court by applying marl; (fn. 195) in the 1680s, however, most of the estate in Peppard was sold, so that in 1725 the Stonors' land was confined to the area between Peppard Lane and Kingwood Common. At that time most of the land was leased to John Clark, although the woodland was still in hand. (fn. 196) An account records the cost of felling different types of wood in the parish, including 'town billet', 'water wood', 'stackwood', and bavins, most of which was probably intended for sale as fuel. (fn. 197)

Tenant Farming

The mixed farming practices of the later Middle Ages continued throughout the period 1500–1800, the chief crops being barley and wheat, with some rye, oats, mixed grains, and legumes. Livestock included horses, oxen, cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry. Stores of grain, cheese, and bacon were frequently kept, in some households alongside other meat such as beef, together with malt and hops for brewing, honey, and fruit. (fn. 198) There is little evidence of specialization for the market, but some farmers evidently engaged in trade: for example, the yeoman Griffin Jemott (d. 1676) held £80-worth of cash and grain at Henley. (fn. 199)

As well as the implements of husbandry, many (but apparently not all) farmers owned tools for felling and working wood. John Benwell (d. 1635) kept bills and axes, which he no doubt used in 6 a. of wood purchased in Rotherfield Greys in 1631, while William Blackall (d. 1694) bequeathed to his wife the right to fell, cut and take firewood for her own use for life. Both families retained woodland in the 18th century (mostly in Peppard), of which some was intended for sale: thus Robert Blackall (d. 1745) specified that his wife could cut and sell wood worth £10 a year in three named coppices. (fn. 200) Many households must have owned gardens and orchards, valued both as a source of produce and pleasure, although they are not well documented. Walter Clark (d. 1675) left his wife a 'garden plot against the hall window next to the lane and so down to the pond's side with the fruit growing on it', while John Blackall (d. 1670) left apples growing worth £2 10s. (fn. 201)

When the Stonor estate was surveyed in the 1660s, the demesne was leased to six different tenants in parcels ranging from 20 a. to 92 a., for terms of 7 or 21 years, and at rents of between 5s. 10d. and 10s. an acre. Eight other leaseholders held a total of 68 a., on terms of 99 years determinable upon lives, for low annual rents amounting to £2 19s. 4d., while 11 copyholders (four of whom were also demesne lessees or leaseholders) held a total of 234 a., mostly for three lives, for rents amounting to £6 8s. 8d. a year. (fn. 202)

By this time a number of the parish's farms can be identified. Henry Round held Gillotts, in the east of parish, while the copyholder John Clark occupied land belonging to Colmore farm (near Kingwood Common). The farms of Cowfields (Cuffalls) and Highlands (Hellons), both Stonor properties, were mentioned in a list of dues collected by Eldridge Jackson (rector 1673–97), alongside other holdings which cannot be located. (fn. 203) Throughout this period, most farms in the parish were leased, either from the Stonors or their successors. Only occasionally were farms owner-occupied: Highlands, for instance, was bought in 1684 by Robert Hanson, who died as a yeoman of the parish in 1711. (fn. 204) Even the eponymous farms owned by the Sadgrove and Slater families were leased to tenants in the late 18th century. (fn. 205)

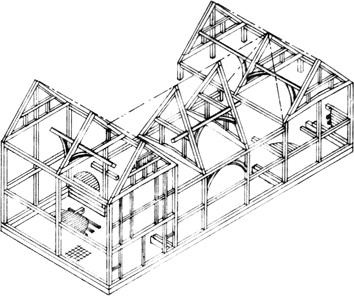

77. Cowfields Farm from the north, with (right) a conjectural reconstruction of its original form, with a central open hall and cross wings. Successive remodellings reflect the prosperity of the house's yeoman occupants.

A number of families lived in the parish for several generations, among them the Benwells, who occupied Cowfields farm from the late 16th century to the early 19th. (fn. 206) William Benwell (d. 1669) was assessed on five hearths in 1662 (one of the highest assessments in the parish) and leased land from the Stonors; (fn. 207) in the 18th century the farm covered 226 a. including wood in Kingwood and meadow in Peppard mead, and was held on 11-year leases at £116 a year. (fn. 208) The farmhouse's irregular four-bay north front (Fig. 77) reflects successive rebuildings by the family and their successors, most of whom appear to have been prosperous. Part of the original open hall survives in the central bays, although limited smoke-blackening suggests that a ceiling, at collar-beam height, was probably inserted in the 17th century. At about the same time the end bays were replaced by two timber-framed and brick wings, of two storeys, with a cellar and attic on the eastern side. The infill of the timber-framed central bays, originally of wattle and daub, has been partly replaced by bricks with added timber studs. In other places, too, the fabric has been repaired, including the four-gabled south front, which was extended in the 20th century. The house lies on the south-eastern side of a large square courtyard bounded by substantial outbuildings, including a six-bay barn of 18th- to 20th-century date. (fn. 209)

Alice Clark of Kingwood (d. 1561), who left bequests of grain and livestock and owned a harrow, is the earliest known member of a family who probably lived at Colmore Farm until the mid 18th century. (fn. 210) The descendants of Griffin Jemott (d. 1676) occupied Peppard farm until the 1780s, while the Sadgrove family owned Sadgrove farm from the late 17th to the early 19th century. (fn. 211) At Sadgrove the surviving 18th-century house forms a long, narrow range of five bays and one-and-a-half storeys; originally timber-framed, it was later rebuilt in red brick with blue burnt headers and stretchers. (fn. 212)

By the end of the 18th century the parish contained eight farms: from east to west, Gillotts (40 a.), Highlands (140 a.), Cowfields (226 a.), Blount's Court (318 a. in Peppard, Harpsden, and Shiplake), Slater's (75 a.), Peppard (205 a.), Sadgrove (34 a.), and Colmore (104 a.). In addition, Kingwood farm (in Shiplake) and Wyfold (in Checkendon) held land in the south-west of the parish, while Harpsden Court farm and Sheephouse farm (both in Harpsden) held land in the far east. There were also a number of smallholdings. (fn. 213)

Farming in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Land Use

When mapped in 1840 the parish's farms were relatively compact. Some (such as Cowfields farm) were confined to the parish, while others included land in neighbouring places. All were predominantly arable: more than 1,500 a. were ploughed in 1840, about 70 per cent of the available land. Permanent pasture (including the commons) amounted to little more than 300 a. (15 per cent), and woodland occupied 275 a. (13 per cent). (fn. 214) As at Greys, the chief crops in the late 19th and early 20th century were wheat, barley, oats, and root crops (especially turnips and swedes). (fn. 215)

The tide of arable farming turned in Rotherfield Peppard at the onset of agricultural depression in the 1870s. By 1879 the arable acreage fell to 1,364 a. (about 62 per cent of the parish), while that of grass and wood increased. (fn. 216) Thereafter, as in other parts of the Oxfordshire Chilterns, livestock (especially dairy) farming increased at the expense of arable husbandry. (fn. 217) As at Greys, cherry orchards flourished, especially around Kingwood Common. Three fruiterers were recorded in 1851 and 1871, while in 1881 Peter Butler was listed as a fruit farmer. (fn. 218) The changes were particularly noticeable on those farms bought by George Shorland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries from the Blount's Court and Mackenzie estates. When offered for auction in 1927, Cowfields farm included 95 a. of arable, 108 a. of grass, and 11 a. of wood, compared with more than 220 a. of arable in 1840. In 1938 the arable acreage was even smaller at 58 a., and there was 145 a. of grass. Shorland's Rectory farm (71 a., made up of former glebe and land belonging to Blount's Court farm) was wholly under grass, and included pigsties, a cowshed, and a stable. (fn. 219)

In the west of the parish, Park farm included 46 a. of pasture in Peppard in the 1930s, which in 1840 had been arable. The tenants were pig farmers engaged in breeding and fattening, and the buildings included a Danish-type pig house. Much of the pasture was 'badly rootled' by pigs, and although by 1940 some land had been ploughed to meet wartime demands, a government inspector thought it would require ample manuring to produce successful crops. (fn. 220) During the Second World War, the amount of arable in the parish undoubtedly increased. Rectory farm, for example, was described as practically all arable in the early 1940s, though it suffered from lack of attention at vital periods. Most farms at this time were mixed, although the emphasis remained on dairying, poultry, and pigs, and some farmers lacked experience of growing crops. At Colmore farm, which sold milk for retail, the farmers had little knowledge of arable management and no arable equipment, though a few acres were under wheat, oats, and other crops. By contrast, at Highlands farm, where the buildings and 12 a. were occupied by a poultry farm in the 1930s, other land (about 58 a.) was ploughed and the crops were described as looking remarkably well. (fn. 221)

Mixed farming continued in Peppard in the second half of the 20th century. At Cowfields farm (250 a.), purchased by R. S. Green in 1956, livestock included cattle, sheep, and poultry, while the arable produced oats, wheat, and barley. (fn. 222) In 1964 Wyfold Grange (254 a. in Peppard and Checkendon) was a highly productive mixed farm, used mainly for barley growing and cattle rearing, and well known for its pedigree herd of Aberdeen Angus cattle. (fn. 223) In 1970 five farms were recorded in the parish; the principal crop was barley, and livestock still included dairy cattle, pigs, poultry, and sheep. Thereafter both arable and livestock farming declined, although an organic farm near Littlebottom Wood was established in the late 20th century. (fn. 224)

Landlords and Tenants

Until the break-up of the large landed estates in the early 20th century most farms in the parish continued as leasehold, either on yearly tenancies or for longer terms not exceeding 21 years. For example, Blount's Court farm (318 a.) was leased to Thomas Stevens in 1837 for 21 years at an annual rent of £465. (fn. 225) Rents fell during the agricultural depression, which may have encouraged landlords to sell. Thus Peppard farm (314 a. in Peppard and Harpsden) was leased by K. R. Mackenzie to Charles Butler for a term of 3 years in 1904 at the 'inadequate' rent of £104 10s. a year. (fn. 226) Not all rents were so low, however: on the Fleming estate, sold in 1913, Colmore farm (75 a.) and Sadgrove farm (111 a.) were held on yearly tenancy agreements for annual rents of £66 10s. and £82 14s. respectively. (fn. 227)

The sale of estates had a number of effects on farming in the parish, including the (re)appearance of owner-occupiers, changes in the size, shape, and number of farms, and the separation of farm buildings from the land. The increase in owner-occupation began before the First World War. Colmore farm and Sadgrove farm were purchased in 1913 by their respective tenants, Thomas Pollock and George Ford, whose families still farmed them in the 1930s. (fn. 228) Other owner-occupiers included H. W. Hooper, who farmed part of the former Mackenzie estate at Highlands (58 a.) and Gillotts (27 a.), and George Shorland, who purchased former glebe, and land belonging to Blount's Court and Sheephouse farms. (fn. 229) Nevertheless some large landowners remained, including Lord Knollys, owner of the Blount's Court estate, and Mrs Pipe Wolferstan, who in the 1940s sold Peppard farm (150 a.) to the tenant, Harold Long. (fn. 230)

The boundaries of the farms mapped in 1840 changed over time as a result of sales and the decisions of landlords. Even farms which retained roughly the same acreage experienced boundary changes, such as Cowfields, which gained land on the east from Highlands farm and lost it on the west to Crosslanes, to create the more compact holding sold in 1938. (fn. 231) The farmhouse at Blount's Court, sold by the Knollys family to the Crowsley Park estate with 103 a. in Harpsden and Shiplake, was wholly divorced from its land in Peppard, part of which was taken into George Shorland's newly-created Rectory farm; the remainder (after its sale to Shorland) was farmed from Kidmore. (fn. 232) The smallest of the late 18th-century farms were amalgamated with their neighbours early on, Highlands farm and Gillotts, for instance, being combined under Daniel Piercy in 1802. (fn. 233)

The creation of larger farms, and changing farming practices, meant that some farm buildings and residences were no longer required and were detached from the land. Before 1851 the house at Gillotts was transformed into a desirable residence by W. D. Mackenzie, with extensive landscape gardens, and later became a school. (fn. 234) Slater's farm (75 a. in 1881) was broken up in the early 20th century and the house became a private residence. (fn. 235) Buildings at Highlands farm were separated from the land when it became a poultry farm after the First World War, (fn. 236) and in the early 21st century the site was occupied by a business park. Colmore farm ceased to be a working farm after the Second World War. (fn. 237)

Despite the trend towards larger farms, some smallholdings survived into the mid 20th century, although many were in a poor state in the 1930s. (fn. 238) City farm, for example, was the rather grand name for 3 a. held by Jesse Butler at Kingwood Common, on which he grew cherries and kept 5 cattle and 28 poultry in the early 1940s. (fn. 239)

Rural Trades and Industry

The usual trades and crafts were practised in Rotherfield Peppard from the Middle Ages, often alongside agriculture. Tenants with surnames such as Carpenter, Cooper, Smith, Tailor, Tanner, Turner, and Wheeler were presented before the manorial court in the 14th and 15th centuries. (fn. 240) In 1295–6 six brewers were fined for breaking the assize, while in 1405–6 a carpenter was paid for repairing the mill. (fn. 241) Blacksmiths were recorded in the parish from the 16th to the 20th century, including the Perrins and later the Pigdens of Crosslanes, who built the surviving house. (fn. 242) The Burgess family of Kingwood were wheelwrights in the 18th and 19th centuries. (fn. 243) William Crutchfield (d. 1758) was a cordwainer, and about the same time Edward Sadgrove was a cooper. (fn. 244)

In 1811–31, 18 or 19 families (about 20 per cent of the total) were employed in trade, manufactures or handicraft, and in the later 19th and 20th centuries a wide range of trades and crafts were recorded, most notably those concerned with the preparation and sale of food and clothes, and others which involved working with wood, stone, and brick. Women worked as dressmakers and seamstresses and in various other capacities, while travellers living in tents on Kingwood Common included a basket-maker. (fn. 245)

A considerable number of bodgers, who made chair legs and spars, and later tent pegs, lived in nearby settlements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Stoke Row, Highmoor, and Witheridge Hill. (fn. 246) Surprisingly, none are known in Peppard, perhaps because the owners of the parish's woods did not permit them to practise their trade there. Certainly some landowners held sporting rights, and employed gamekeepers to protect their woods. (fn. 247)

Small chalk and gravel pits were dug throughout the parish, mostly by local farmers for improving the soil and for mending roads. (fn. 248) From the early 20th century more commercialized gravel extraction also took place, including at Littlebottom Wood, Highlands Farm, and in the far east of the parish. (fn. 249)

Milling and Paper Manufacture

A mill worth 20s. in 1086 stood presumably on the site of its late medieval successor on the Thames. (fn. 250) In 1289 it belonged to Ralph Pipard and was used for grinding grain; called Marsh (Mersche), it lay opposite a mill on the other side of the Thames in Remenham. (fn. 251) The two mills shared a weir called Marsh Lock, where a winch hauled boats travelling upstream from London through the flashlock. In about 1395 William Drayton (presumably a relation of the lord of the manor John Drayton) was alleged to have neglected to carry out repairs at the mill, then called Meadow mill (Meedmelle), with the result that 'the said lock is now stopped up with sand, gravel and the increase of the water, and the winch altogether taken away so that boats and shouts cannot be drawn or navigated there'. (fn. 252) The complaint produced the desired effect: in 1405–6 timber and iron were bought to repair the winch. The carpenter employed to carry out the work, Robert White, leased the mill and fishery from Faukener and Drayton, and thereafter the lock at Rotherfield Peppard was passed without difficulty. (fn. 253)

In 1462 Robert West leased the watermill from Richard Drayton for a term of 10 years at a rent of £2 a year, and agreed to build anew two mills, the weir, waterworks, and bridge, and to repair the mill house. (fn. 254) The mill belonged to Francis Stonor in 1585, (fn. 255) but little is known about its management until the late 17th century, when it was held by Bartholomew Quelch (d. 1679), whose goods included 20 meal sacks. (fn. 256) By that time the mill was known as New Mill, and after expansion as New Mills: in 1705 the Stonors held five water corn mills there. (fn. 257) Thomas Quelch (d. 1716) succeeded to the family milling business, but his sons pursued different careers, and Thomas Harris (d. 1751) took over the lease. (fn. 258)

In 1786 four water corn mills occupied by Messrs Westbrook and Whiting were destroyed in an arson attack, (fn. 259) and when rebuilt shortly afterwards were replaced by a flour and paper mill. Those were burnt down ten years later but evidently replaced, (fn. 260) and in 1798 the timber-built and tiled mills were acquired by John Elsee, a paper manufacturer and miller. (fn. 261) Charles Elsee (d. 1855) took over the business c. 1820, and in 1841 sold the mills to William Thomas Knollys. (fn. 262)

Paper and flour were manufactured at New Mills throughout the 19th century, employing 30–40 people in 1840. (fn. 263) In 1861 the paper manufacturer James Allen employed 11 men and 4 boys, including several paper-makers and engineers who lived in nearby tied cottages. (fn. 264) The two mills straddled a single millrace, one lying on the river-bank, the other on a small island in the Thames. (fn. 265) C. H. Smith and Sons were still paper-makers there in 1903, but the buildings were ruinous in 1915, and by 1925 both mills had been demolished. (fn. 266)

A horse mill was recorded in 1432, when the miller charged excessive tolls; (fn. 267) in 1470 it was held of the Stonors for 6d. rent. (fn. 268) That or another horse mill was among properties in Peppard, Mongewell and Lewknor disputed between Thomas Stonor and William Lendall in 1532. (fn. 269)

Shops

No references to shops in Peppard survive until the 19th century, although presumably goods were sold from houses and workshops or by itinerant salesmen, such as the cheesemonger William Warner (d. 1680). (fn. 270) From the 18th century local publicans also acted as victuallers, and a shopkeeper was recorded in 1847. (fn. 271) After 1860 there were at least two shops: a baker's near Peppard Common, and a grocer's near Kingwood Common. In the early 20th century their role as general stores may have been assumed by the two sub-post offices. (fn. 272) However, as at Greys, most inhabitants probably travelled to Reading or Henley for the bulk of their shopping.

A commercial garage, later called Hillcrest Motors, was established by Albert Butler about 1920 along Blount's Court Road, and remained open in 2007. (fn. 273) A similar business on Reading Road was part of the Shorland estate sold in 1938. (fn. 274) In the 19th century the Butler family also established a building firm in the parish, whose former yard was developed for housing in the early 21st century. (fn. 275) In 2007 business parks were located at Newtown (in Henley), Highlands Farm, and Peppard Lane.

Medicine and Technology

Local innovations in medical care were largely due to Dr Esther Colebrook (1870–1957), who began a general practice in the area, and in 1902 founded a sanatorium (later the Peppard Chest Hospital) for the open-air treatment of tuberculosis. The hospital expanded rapidly in the early 20th century, becoming part of the NHS in 1948. It employed a considerable number of medical and other staff before closing in 1980. (fn. 276)

Technological breakthroughs in the parish followed the conversion of Blount's Court into laboratories in 1960, by its new owners, American Machine Foundry Ltd. In 1964 Brooke Bond Tea Ltd bought the premises, and in 1975 the site was acquired by Johnson Matthey and Co., the owners in 2007. The firm developed the catalytic system to control car exhaust emissions, and later worked on platinum anti-cancer drugs. (fn. 277)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Social Structure and the Life of the Community

From the Middle Ages Rotherfield Peppard remained a predominantly agricultural community. Lords of the manor were intermittently resident until the early 18th century, after which a succession of minor gentry exhibited a limited but philanthropic interest in community life. Most inhabitants, however, were relatively low-status farmers and agricultural workers. The few yeoman farmers enjoying greater wealth played a prominent part in church and parish activities in the 17th and 18th centuries.

From the 19th century the parish attracted a growing number of wealthy residents who built or improved a range of exclusive houses, although until the late 20th century the community remained socially mixed. Several public buildings, including church, school, memorial hall, public houses, and sporting facilities, provided a focus for parish life.

The Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages most inhabitants were tenants of the Pipards and their successors, although the large number of freeholders recorded in the early 14th century, (fn. 278) combined with the lords' frequent absenteeism, suggests that many probably enjoyed considerable independence. Court rolls of the mid 14th and mid 15th century indicate relatively limited seigneurial control, allowing tenants to evade rents and to ignore a variety of injunctions. (fn. 279)

The principal settlements at Peppard Common and Kingwood Common seem not to have been distinguished by function or status, and both probably had a mixed population in terms of landholding, wealth, and occupation. Early 14th-century tax returns do not show a marked polarization of local society. In 1327, apart from John de Alveton (who paid 6s. 8d.), 12 inhabitants contributed between 6d. and 2s., with a median of 15d.–18d. (fn. 280) Most were probably customary tenants holding a yardland or half a yardland, and were the successors of the Domesday villani. Matilda Bolle, for example, who paid 2s. in 1327, may have occupied the half-yardland held later in the 14th century by Gilbert Bolle. The names of several other early 14th-century taxpayers also appear in court rolls of the period 1351–66, indicating a degree of social stability, though by 1456–67 there seems to have been a much greater turnover of tenants. The parish's smallholders, successors to the Domesday bordars and slaves, probably fell below the tax threshold, among them the cottager John Balet (d. 1351). (fn. 281)

The Pipards built a house at Rotherfield Peppard (recorded for the first time in the late 13th century), maintained a deer park, and were occasionally resident. (fn. 282) Nevertheless, Peppard was not their principal seat. The family held lands stretching from Gloucestershire to Suffolk as well as in Ireland, and Ralph Pipard (d. 1303) was particularly attached to the Buckinghamshire manor of Great Linford. (fn. 283) Despite giving their name to the parish the family left no lasting legacy, therefore: the location of their house is unknown, and there are no surviving memorials to them in the parish church. Likewise the Butlers, earls of Ormond, had a limited impact during their lordship (1331–91), living for the most part in Ireland. (fn. 284) Their authority was maintained by an attorney-general, John de Alveton (d. 1361), and by the holding of regular manor courts. (fn. 285) After Alveton's death the most influential landowner in the parish was Thomas Blount (d. 1407), whose son John was wrongly described as lord of the manor in 1412. (fn. 286) Around the same time the Pipards' former manor house was leased, the new joint lords of Peppard manor almost certainly living outside the parish. (fn. 287)

1500–1700

Surviving tax records suggest that the lack of marked social stratification persisted into the 16th and 17th centuries. In 1515 eleven taxpayers were assessed on goods valued between £2 and £10 (with a median of £3), while in 1543 the goods of 16 inhabitants were valued between £1 and £9 (with a median of £2). Excluding Blount's Court and the rectory house, the hearth tax of 1662 was assessed on 21 households each with between one and five hearths; the mean, however, was only 1.6, and in 1665 five out of 16 households were discharged payment through poverty. (fn. 288)

Even so, there were considerable gaps between the most prosperous and the poorest, and occasional hints of social conflict. The value of 17th-century probate inventories ranged from just over £7 (the labourer Robert Rose) to more than £337 (the yeoman Griffin Jemott), with a median of just over £44 and a mean of about £80. (fn. 289) In 1689 'three sturdy vagabond rogues' attacked the yeoman farmer Robert Hanson, and about the same time there was concern to prevent a labourer, Henry Dolton, from settling in the parish because he might claim poor relief. (fn. 290) Augustine Knapp (d. 1602) acknowledged the plight of the 'poor, lame, impotent and needy people' of the parish by establishing a clothing charity, and his example was followed by others. (fn. 291) Other Peppard yeomen and husbandmen made bequests to the church and served as parish officers. (fn. 292)

Evidence of the size and layout of houses at this period is provided by probate inventories, of which 47 survive for Rotherfield Peppard between 1594 and 1735. Most of the larger houses (of four rooms or more) were recorded after 1670; before then smaller houses seem to have been more common, a change presumably reflecting increased prosperity and rising standards of living. Most inventories listed a hall and one or more chambers, while a kitchen was mentioned in ten houses, with less frequent references to a buttery, cellar, and milkhouse. (fn. 293)