Pages 405-438

Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

CHAPTER XVI. West of Penton Street

Nowhere in the old parish of Clerkenwell is a sense of the original building pattern having been swept away stronger than on the western slopes of Pentonville. A stroll downhill from Penton Street along Donegal Street and Collier Street, which together constitute an east-west spine for this area, unfolds a miscellany of housing estates, schools and other large buildings that turn their backs on the frontage of the streets that cut between them. Here, until the urban density of King's Cross looms close, architectural value is primarily attached to the blocks and the spaces within them, in a classic inversion of what cartographers call the figure-ground relationship.

Only in Northdown Street, the most westerly and the latest portion of this district to be completed in the 1830s and 40s, are any remnants of first development to be found. Elsewhere no trace survives of what was once a populous suburb and at first passed for a prosperous one. Yet here was once the core of Pentonville, which from the 1770s crept westwards from Penton Street and northwards from the New (now Pentonville) Road along a neat grid of streets. In some cases not even the streets survive, while most that do have changed their names. Nevertheless the regular, stolid impress of the original grid can still be felt. Along Pentonville Road, from Cynthia to Rodney Street is much the same distance at around 275 ft as from Rodney to Cumming Street, or again from Calshot Street to Killick Street or from there to Northdown Street.

526. Calshot Street looking south in 2007. On right, The Wintons

Buildings built since the Second World War dominate the district today, a high proportion of them housing estates. The outstanding and challenging example is Lubetkin and Tecton's Priory Green, first planned in 1937 but not in the event built until 1948–58. Priory Green is a monument not only to the utopian ambitions of housing architecture in its day, but to the culmination of efforts dating back to the 1860s to rid Pentonville of a legacy of banal and decrepit housing. The post-war purgation that swept away many minor Georgian terraces removed also most of the copious Victorian attempts to improve the area. A complete new street of that period, Affleck Street, has left only a tiny stub, while once again it is only in Northdown Street that blocks of model dwellings survive.

In its early prime, western Pentonville was not without appeal, grace or famous residents. Here John Stuart Mill was born, here Mary Wollstonecraft and Thomas Carlyle both briefly lodged. Writing in Southampton (now Calshot) Street in the autumn of 1824, Carlyle found his rooms 'about the neatest I ever inhabited; papered and cleaned like bandboxes, and quieter than I supposed any were in this monstrous place [London]. The people go to bed early; after half past ten, there is scarce a murmur to be heard till towards seven in the morning; and throughout all the day there is nothing that even approaches to noise'. (fn. 1)

That elusive and short-lived tranquillity can only be recaptured today in a handful of engravings and documents. The main flavour of the environment today is of a backwater where railed-off housing estates and schools have emptied the public realm of meaningful life, and where the intermittent traffic is perilous enough to make the ear- and eyesore of speed-bumps omnipresent (Ill. 526, 527). Much effort has been spent on this area over the years and there is remarkable architecture to be found. But it has to be admitted that western Pentonville is hard work.

527. Donegal Street looking west in 2007

The western and northern boundary followed here is one of convenience, and conforms neither to the old parish boundary (Ill. 426) nor its line as simplified under the London Boroughs Act of 1900, when the civil parishes were redefined as boroughs.

First Development

An outline history of Pentonville is given in Chapter XIII. In broad terms, Henry Penton's new suburb progressed northwards from Pentonville Road and eastwards and westwards from Penton Street. In the district covered by this chapter, the earliest building began in the 1770s, between Penton and Rodney Streets. By 1790 that first sector had been quite tightly filled in up to the parish's northern boundary with Islington, at which point all the north—south streets of Pentonville stopped abruptly, with fields beyond. The main subsidiary streets within this quadrilateral were John Street, now represented by the stub of Risinghill Street, and Henry Street, now Donegal Street. There were also two minor north—south streets running north out of Pentonville Road: Hermes Street, which once extended up to John Street but has since been obliterated except for its southern extremity, next to Pentonville Road; and Ann Street, now Cynthia Street, which ran only as far as Henry Street (Ill. 528).

West of Rodney Street, building agreements were made in 1786–9 with separate individuals for three large, parallel blocks stretching back to the parish boundary and to be divided by roads leading out of Pentonville Road. The watchmaking brothers Alexander and John Cumming took on the blocks between Rodney Street and Cumming Street and between Cumming Street and Southampton (now Calshot) Street respectively, while between Southampton Street and Winchester (now Killick) Street the undertaker was the bricklayer Joshua Hodgkinson. All three blocks got quickly under way. By the time of Horwood's map of 1799, development had taken place all along the Pentonville Road front and up each of the new streets leading out of it as far north as Collier Street. North of that line, Horwood shows houses only in Winchester Street. Collier Street, the sole cross street in this quarter of Pentonville, appears on his map only as a stub starting from Rodney Street, but had probably progressed further. A fifth and final parallel street to the west, North (now Northdown) Street, had not then got far out of Pentonville Road.

By 1808 Collier Street had been completed, and is indeed shown on Hornor's map of that date as extending briefly beyond North Street to the western parish boundary, covering sites later built over. But there was still only intermittent development along North Street and north of Collier Street—a token of the slow-down in building during the Napoleonic Wars. Writing in about 1803, J. P. Malcolm remarked of this part of Pentonville: 'The streets are broad, and their descent keeps them always clean; it is no wonder that the houses produce good rents. Whenever the blessings of Peace are restored, this place will again increase in a very rapid manner'. (fn. 2) The only fresh street laid out after that was Wellington (later Busaco) Street, an afterthought in the form of a long cul-de-sac tucked in from about 1810 between the backs of houses in Cumming and Southampton Streets north of Collier Street.

528. The Penton estate west of Penton Street, from Horwood's map of 1799, showing development of streets north of the New (Pentonville) Road. Collier Street, shown as a stub running west out of Rodney Street, may have advanced further than indicated. The development extended north of Henry Street beyond the border of the map

The westernmost portion of this district had a different history. In that direction Henry Penton III's landholdings extended north and west beyond the Clerkenwell boundary, to include a substantial tract in Islington parish. For his land in both parishes west of Winchester (now Killick) Street, Penton in 1802 drew up an agreement with the builder William Horsfall, and then in 1806–7 sold him the freehold of the whole. The west side of Winchester Street and both sides of North (Northdown) Street, though begun under Penton, were therefore built up in a separate manner and took until the 1840s to complete. Here courts behind the street fronts were commoner than further east as far as Penton Street. The character of this area was doubtless influenced by the proximity of the Regent's Canal, on which Horsfall developed what is now Battlebridge Basin (1825); by the creation of Caledonian Road; and eventually by the coming of the Great Northern Railway to King's Cross in 1850, a turning point in Pentonville's fortunes.

529. Hermes Hill area from Hornor's map of Clerkenwell, 1808–9. Hermes Hill House and its garden are shown north of John Street, with the north and south pavilions to their west

The layout of western Pentonville broadly continues the grid of streets set out to the east of Penton Street, but west of Rodney Street there is a single east—west street, Collier Street, instead of two. This may have all been set out in the 'plan for building' produced by James Carr in 1781, though minor modifications are likely to have been made, for instance in the formation of Ann (Cynthia) Street on the block of ground taken by the merchant Robert Harrop in 1769. Carr was still involved with work on the estate many years later, for instance in connection with Alexander Cumming's ground on the south side of Pentonville Road in 1791, and the Penton Estate accounts record a payment to him in 1805. (fn. 3) The main executive agent was Thomas Collier, Henry Penton III's steward, whose task of making clear agreements and promoting the estate's progress must have been facilitated by the simplicity of the conception. Variations, such as the independent houses built by Dr De Valangin on Hermes Hill, and by John Cumming facing Pentonville Road, as well as the Pentonville Chapel, did not affect the general look of the development.

The following short sections outline the early developments block by block. In view of the drastic redevelopment since then, the street names current at the time are generally used.

Penton Street to Rodney Street

Development in this rectangle was distinguished at its outset in the early 1770s by one remarkable house, Hermes Hill House, built next to the fields looking out towards Islington. On the less eligible ground to its south a grid of smaller streets was subsequently laid out and built up.

Hermes Hill House stood a little north—west of the present St Silas's, Penton Street, on the site now occupied by Chalbury Walk on the Wynford Estate (Ill. 529). It was built in 1772–4 for Francis De Valangin, a Swiss-born physician who practised in Fore Street, Cripplegate, and earlier in Soho Square. De Valangin took a lease of the site from Henry Penton in September 1772, undertaking to build a house costing at least £500. (fn. 4) Large and detached, the house stood in comparative isolation, set back from John Street with a landscaped garden to its west. The site was on the highest part of the estate, backing on to White Conduit Fields and commanding views of London and the Middlesex and Surrey hills. The name was chosen by De Valangin, a mason, in commemoration of the legendary alchemist Hermes Trismegistus. (fn. 5)

Cromwell records that the house was designed by the doctor himself, 'on a plan more fanciful than convenient'. If a professional designer was involved, however, it might have been the Essex architect William Hillyer (d. 1782), for De Valangin's second wife, an Essex woman whom he married in 'about 1782', was the widow of a 'Mr Hillier', variously described as 'an architect' and 'an eminent surveyor and builder', and probably identifiable as Hillyer. (fn. 6)

In its original form, the house consisted of 'a rather singular looking brick tower, with wings descending, as it were, by steps on either side'. (fn. 7) Only the most distant of pictorial representations seems to exist (Ill. 422). Sales particulars drawn up after De Valangin's death describe it simply as a 'uniform brick residence with extensive front'. It faced west towards the garden, and comprised two principal floors, with servants' apartments and a belvedere or 'prospect gallery' above, together with two small apartments 'on the leads'. There were five bedrooms (with two dressing-rooms), three on the first floor and two downstairs, where the dining-parlour and a study or breakfast parlour were also situated. The drawing-room was on the first floor, approached by main and service staircases, and there was a spacious entrance hall. (fn. 8)

De Valangin had a valuable library and a collection of pictures by 'esteemed masters'; the drawing-room was ornamented with a painting in the ceiling, 'representing the sleep of Endymion on Mount Latmos, as caused by Cynthia, who rests on a cloud regarding him'. (fn. 9)

The garden was laid out with walks and planted with fruit trees and flowering shrubs. Its main feature was a large fishpond, and it also included the tomb of De Valangin's daughter, who died in childhood in the 1780s. Cromwell records that the house was initially supplied with water from the White Conduit built to serve the Charterhouse. (fn. 10)

In 1776 De Valangin leased a large plot adjoining his house to the west, bounded by Rodney and John (later Risinghill) Streets. This was developed from the late 1770s to the 1790s. The houses here included several on the east side of Rodney Street and a pair of villas, North and South Pavilions, which stood at the west end of the Hermes Hill garden (Ill. 529). These villas were square on plan and seem to have been of one storey only; they each contained two bedrooms (besides servants' apartments), with a drawing-room, dining-room, and breakfast parlour. (fn. 11) The doctor also leased some other building plots near by.

When De Valangin's estate was sold after his death in 1805, Hermes Hill House became the residence of a timber merchant, Joseph Aldridge, who took down the observation tower and regularized the garden front of the house, and also built a house adjoining, 'at the rear'— presumably, to the north. Aldridge was a disciple of the evangelist William Huntington, SS ('Sinner Saved'), who in 1811 took the house over as his home, residing there until his death in 1813. (fn. 12) In Victorian times the house seems to have remained a private residence for some years but part of the grounds were given over to commercial uses, principally brewing and laundering, from the 1840s.

For years the name Hermes Hill was used to refer rather vaguely to the whole north side of John Street, which was more or less a De Valangin enclave. The painter Thomas Uwins is said to have been born at Hermes Hill in 1782, precisely where is unclear. (fn. 13) (His father, also Thomas Uwins, appears fleetingly in the ratebooks for 1776 at No. 6 Penton Street near by.) (fn. 14) The name was officially abolished in 1880 when John Street became Risinghill Street. It lived on, however, as the name of a cul-de-sac or yard opening off the street and surrounded by commercial and industrial premises, of which Hermes Hill House had become part. Among the activities carried on here were laundering, woodworking, lens-making, bookbinding, printing and publishing. (fn. 15) The Georgian house may have survived in disfigured shape into the twentieth century.

John Street. The early history of the north side of John Street, since 1880 Risinghill Street, is essentially covered by that of Hermes Hill House. The roadway itself must have been partly set out in the 1770s from the Penton Street end as a means of access to Hermes Hill House and the pavilions beyond. But the name of John Street, probably so called after Henry Penton III's grandfather John Penton, is not recorded before 1787, when development had just begun on the south side. Here mainly terracehouses were built between about 1786 and 1790 under the aegis of Penton's steward, Thomas Collier, though there were one or two larger plots near the corner with Hermes Street. (fn. 16) As completed, John Street ran right through from Penton Street to Rodney Street. An engraving of 1818 from Pugin and Brayley's views of Islington and Pentonville, taken from the Rodney Street junction, emphasizes the street's width, with houses stepping up the hill (Ill. 421). It was curtailed to something like its original brevity of the early 1770s when the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (formerly Risinghill) School obliterated the western half of Risinghill Street in the 1950s.

Hermes Street originally ran down from John Street to Pentonville Road, bisected by Henry Street. Taking its name from Hermes Hill House, it was in development between about 1779 and 1788. (fn. 17) It had row houses on its east side and a medley of buildings opposite, including the small charity school connected with Pentonville Chapel, first established in 1788 for twelve boys and twelve girls. The boys transferred to Collier Street in 1811, leaving the girls and infants in Hermes Street till 1871. (fn. 18) The first lessee of a clutch of smaller houses at the south end of this street, along with other such houses in Ann Street adjoining, was Aaron Hurst, the designer of Pentonville Chapel. (fn. 19)

In 1864 James O'Brien (Bronterre O'Brien), the Chartist and political thinker, died after some years bedridden and in poverty, at his house, No. 20 Hermes Street. In 1984 a commemorative plaque was mounted on the wall alongside what is now Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School, unveiled by the historian A. J. P. Taylor. (fn. 20)

Ann Street, now Cynthia Street, stretching only between Pentonville Road and Henry Street, was in development with modest terraces on either side, mostly built between about 1786 and 1790. (fn. 21) Its name no doubt honoured Henry Penton III's first wife; the present name refers to the subject of the painted ceiling in Hermes Hill House. Ann Street was apparently intended originally to connect with John Street, for in his lease to Dr De Valangin of the Hermes Hill House site in 1772, Henry Penton covenanted to leave space for a road through what was then Preston's brickfield, between the Happy Man public house in the New Road and De Valangin's ground. (fn. 22) De Valangin took further ground on the west side of the new street, and later the architect Aaron Hurst was involved in speculation here, leasing a house on the east side to a City merchant, Samuel Walker of Mark Lane, who was involved in other houses in this street. (fn. 23)

Henry Street, renamed Donegal Street in 1906 after the home county of Captain F. T. Penton's wife, was slightly narrower in original width than John Street to its north. But it had a larger number of middling-sized houses. The south side was built up between about 1779 and 1788. East of Hermes Street a narrow alley called Prospect Row had come into existence by 1776. (fn. 24) On this side of Henry Street, the shortish frontage between Ann Street and Hermes Street was leased by Penton to his steward, Thomas Collier, in 1779. (fn. 25) A photograph of 1959, when the buildings here were on their last legs, shows small houses, some two and some three storeys above ground (Ill. 530). Opposite, on the north side west of Hermes Street, a larger take was devolved to Collier and developed by the latter in the late 1780s in partnership with Joshua Hodgkinson, prolific as a developer elsewhere on the Penton estate. (fn. 26) One of the houses built here, No. 27, was the home of the young architect E. B. Lamb, living with his mother there in 1829. (fn. 27)

Rodney Street to Southampton Street

Here four sizeable urban blocks were projected, built up from 1786 onwards. They were centred upon Cumming Street, bounded on the east by Rodney Street and on the west by Southampton (now Calshot) Street, and bisected by Collier Street.

The head developers for these houses were the Scottish brothers Alexander and John Cumming. Alexander was a watchmaker and inventor of high public repute who had been in London since the early 1760s and enjoyed royal and aristocratic patronage; and appears also to have been a shrewd businessman. He was first involved on the Penton estate in development south of the New Road in Penton Place (now Penton Rise), where he built a number of houses under an agreement of 1779, including a villa for his own occupation (see page 301). (fn. 28)

North of the New Road Alexander Cumming divided a larger speculation with his brother and regular collaborator John (Ill. 425). Alexander took the Rodney Street to Cumming Street blocks by an agreement with Henry Penton of January 1786. (fn. 29) John followed on with the Cumming Street to Southampton Street blocks in November 1789.

530. Donegal Street looking east towards Penton Street in 1959, with Risinghill School nearing completion in foreground. White Lion Street School in left background. All houses in Donegal Street demolished

Alexander Cumming's take between Rodney Street and Cumming Street seems to have been quite quickly built up, with a flurry of leases dated 1788–9, though the Cumming Street side may have taken longer to complete. (fn. 30) It was perhaps the best in the whole of Pentonville, forming a kind of centrepiece to the development (Ill. 531). Here stood wide-fronted terrace houses with spacious gardens set back behind Pentonville Chapel (1787–8), of which Cumming was the chief promoter, since its site formed part of his ground (see page 355). The original concept of two large houses flanking the chapel and facing the Pentonville Road came to nothing, but those who chose houses on the back part of this block south of Collier Street had the spatial amenity of the chapel's burial ground behind their gardens.

Starting a little later, John Cumming elected to treat his two blocks between Cumming Street and Southampton Street a little differently from his brother. In 1788–9 he built himself a substantial detached house, Cumming House, facing the New Road, flanked left and right by the short terraces of Cumming Place (see page 354). The frontages behind on the west side of Cumming Street and east side of Southampton Street were then partially developed with terraces of the early 1790s in the regular way. (fn. 31) But a generous open space was left between their back gardens, no doubt to leave an unimpeded view northwards to the country from the back windows of Cumming House.

The death of John Cumming in 1796 and the deceleration of building from about that time compromised this vision. In 1802 his heir James Oswald Cumming assigned part or all of the undeveloped ground back to Alexander Cumming, and there is some evidence for renewed building thereafter. (fn. 32) Nevertheless by the time Hornor drew his parish map in 1808, the block north of Collier Street was less than half built up, and the London Female Penitentiary, whose inmates were scarcely to be flattered with prospects, had taken over Cumming House. That opened the way for an extra narrow street to be driven northwards out of Collier Street midway between Southampton and Cumming Streets. This cul-de-sac, at first called Wellington Street, later became the notorious Busaco Street, the worst of Pentonville's slums. Unlike its fellow north—south streets, it never became connected with the Thornhill estate to its north.

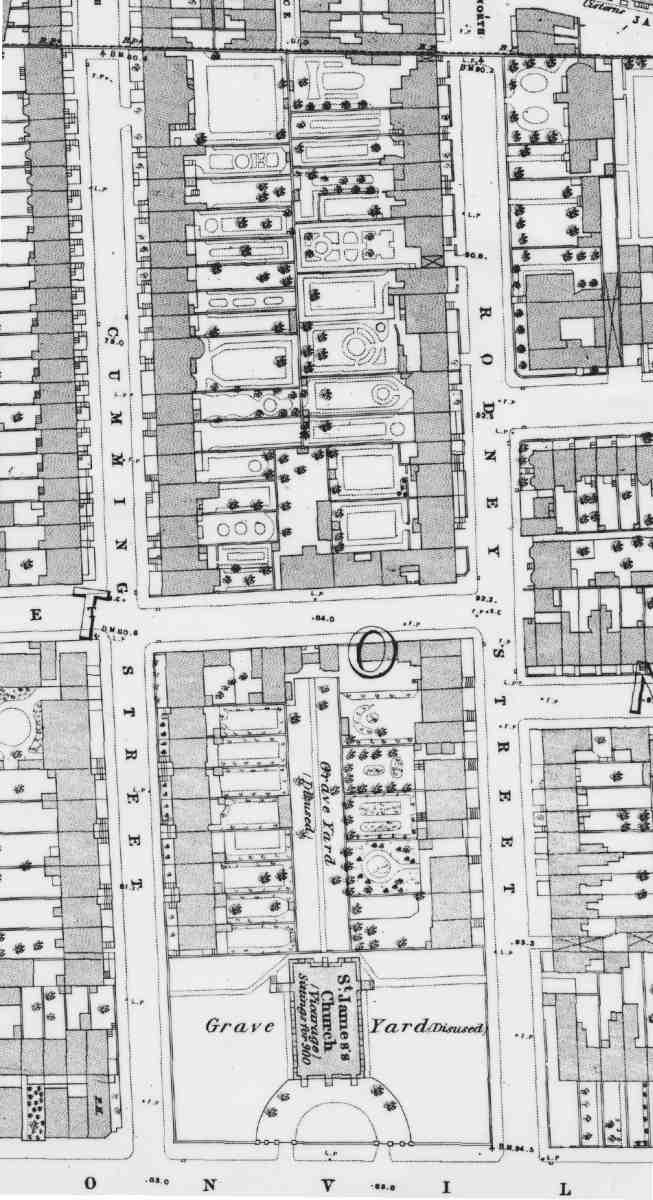

531. Block between Cumming Street and Rodney Street taken by Alexander Cumming in 1786, with Pentonville Chapel (St James's Church) and burial ground. From Ordnance Survey of 1871–4

An intriguing aspect of the Cummings' Pentonville activities is their musical connections—specifically, their passion for organ-building. Alexander Cumming first came to fame for an organ he and his brother assembled at Inverary Castle for the Duke of Argyll. Later he built a machine organ for the Earl of Bute, which he bought after Bute's death in 1792 and installed at his home in Penton Place (see page 301), where he was rated for an 'organ shop'. (fn. 33) Cumming is known to organ-building scholars primarily as the inventor of the double-rise reservoir bellows. Three of his 1780s leases in Pentonville were to organ-builders: to John Wright of Clerkenwell, John King of St Pancras and Joseph Beloudy or Bellondie of Clerkenwell. (fn. 34) Both Beloudy and King feature in lists of British organ-builders, King having his address in Collier Street as late as the 1820s. (fn. 35) Another possible connection comes through Francis Linley, a young blind composer of some note who was organist at the Pentonville Chapel. (fn. 36)

Rodney Street. The name of Rodney Street, honouring the victorious Admiral Lord Rodney, had been chosen by 1787. Here Alexander Cumming took some additional ground at the top on the east side, where the street ended abruptly in a high brick wall. It was agreed with Penton that the northernmost piece of ground towards the fields would not be built on but 'Paled in with an open pailing and Kept as a Garden by way of Ornament'. (fn. 37) Set back behind this was Rodney House, seemingly an afterthought of around 1800 and described in auction particulars of 1837 as 'a capital abode, suited to a merchant of the first respectability'. The resident at that time, John Stephen Barandon or Barrandon, was indeed probably a merchant of Austin Friars. There were 'views of Hampstead and Highgate from the Observatory at its summit', 'a handsome uniform Front, enclosed with a Parterre and Gravel Walk', and ample gardens. (fn. 38)

The average Rodney Street house was humbler but not insubstantial. Such was the birthplace in May 1806 of John Stuart Mill, No. 12 Rodney Terrace (later No. 13 and ultimately No. 39 Rodney Street), one of what was probably a semi-detached pair with three full storeys and basement on the west side near the top of the street (Ill. 532). His father, James Mill, had abandoned the ministry in Scotland and come to London in 1802 to make his career in journalism. In 1805 he married Harriet Burrow, the daughter of a widow who owned a lunatic asylum in Hoxton. The couple rented the Rodney Street house from Mrs Burrow for £50 per annum. Here James Mill's History of India was begun, but the marriage was not happy. The family moved away in 1810. An LCC commemorative plaque, coloured green and naming both Mills, was erected in 1907, but smashed when the house was demolished for the Priory Green estate in about 1948. (fn. 39) A later resident in the street was the chemist John Stenhouse, who died at his home, No. 17 Rodney Street, in 1880. (fn. 40)

Cumming Street is now half its original length, as the Priory Green estate obliterated its existence north of Collier Street. It has left few visual records. A Victorian or Edwardian postcard view suggests a wide street with plain brick-fronted houses, rising mostly three storeys above ground: Pevsner in 1952 noted one with 'pretty Coade stone decoration'. (fn. 41) In one such house, unidentifiable but most likely south of Collier Street, Mary Wollstonecraft lodged briefly with her daughter Fanny and French maid Marguerite in the spring of 1796. It was not many months before she became entangled with William Godwin and moved west to new lodgings in Judd Place West in order to be closer to him in Somers Town. (fn. 42) Another resident was the marine painter Alfred Gomersal Vickers, who died at his home, No. 20 Cumming Street (north of Collier Street), at the early age of 26 in 1837. (fn. 43) Numbering in this street changed in 1891.

Southampton Street. For a short initial period Southampton Street was called Grace Street, after Great Grace Field, to which the ground here had belonged. (fn. 44) The new name reflects the Pentons' Hampshire background. It was renumbered in 1889 and in 1938 renamed Calshot Street, after a village near Southampton on the Solent. This was the first of Pentonville's north—south streets to be connected with the Thornhill estate in Islington to its north when that district began to be developed in the 1820s.

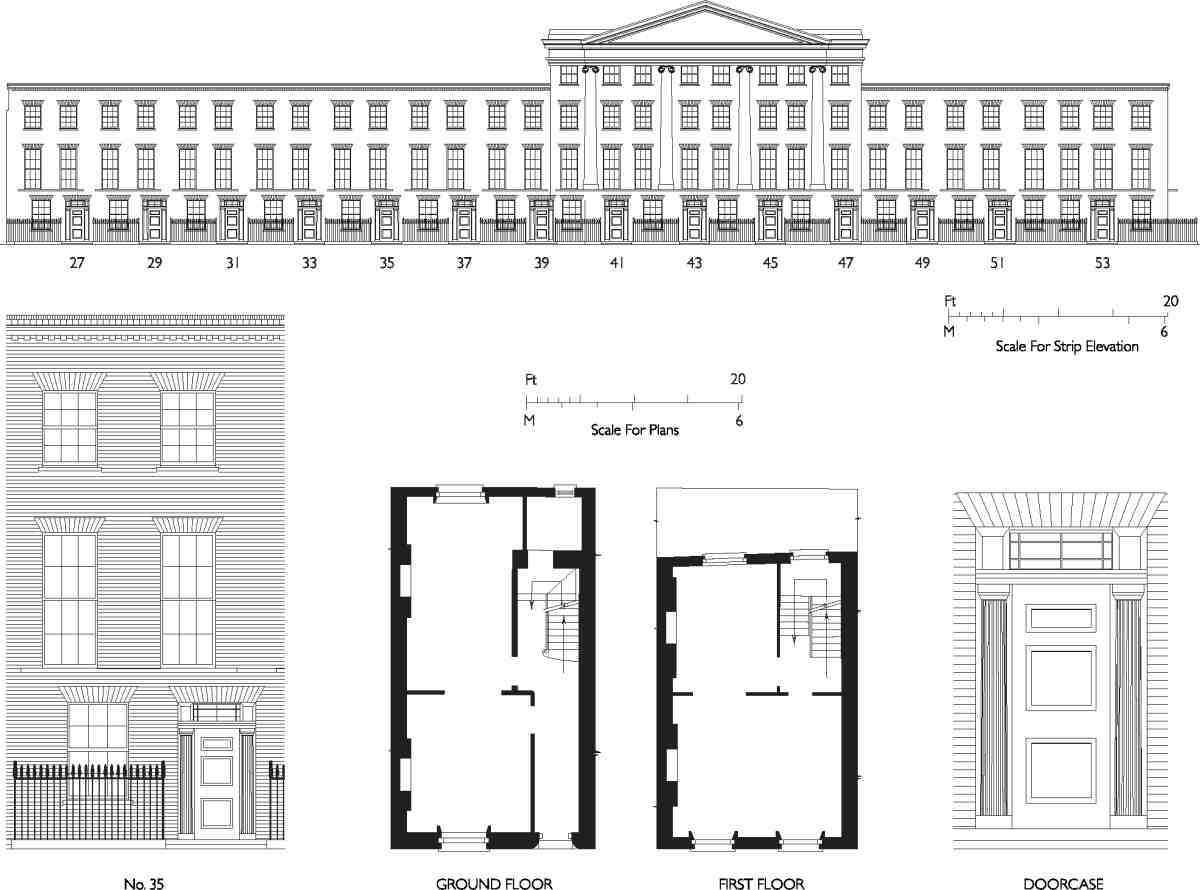

Southampton Street's houses are better recorded than others in this lost portion of Pentonville. In the stretch between Collier Street and Pentonville Road, photographs of the east side in the 1950s show regular threestorey houses with one near the south end, No. 14 Calshot Street, equipped with a handsome Doric doorcase (Ills 533, 535).

Two houses in this row could briefly boast famous residents. It was to the then No. 23 Southampton Street, later

No. 35 and finally No. 18 Calshot Street, that Thomas

Carlyle moved from his friend Edward Irving's house in

Amwell Street in November 1824 during his first extended

visit to London, in order to see his life of Schiller through

the press. 'Ere long I landed in Southampton-street, a fine

clean quiet spot', he told his mother,

and found a landlady and a couple of rooms almost exactly

such as I was wanting. The rent 16/- per week, which is even

cheap for London, was a less matter with me than the comforts of the place, which were certainly such as I never hope

to realize in London. The landlady is a middle-aged cleanly,

substantial, most discreet looking person; she has a tidy girl

for a servant, and one old asthmatical damsel who lodges with

her on the ground floor, for her sole inmates. I occupy the

whole second floor, with my bedroom and parlour, and above

me, there is nothing but two empty rooms, neither of which

is likely in my time to be occupied … The room which is of

moderately large dimensions with two windows looks out

upon a little empty space, neatly paved with clean tiles, the[n]

a green wooden railing, then the flag-stones, then a new smart

street, travelled by few itself, but communicating at the distance of a few yards with the New Road, one of the great thoroughfares in London. The bedroom looks out upon green

plots (one of which belongs to the house), then a field cut with

walks, and beyond this a neat building which I believe is some

public charity [the London Female Penitentiary], and beside

it among other houses the chapel of St James' Clerkenwell,

which affords me the service of a town-clock. (fn. 45)

Carlyle kept the lodgings till February 1825, shortly before

he returned to Edinburgh.

532. No. 39 Rodney Street in 1945, with commemorative plaque to James and John Stuart Mill. Nos 41–45 to right. All demolished

Two doors further up the street, No. 22 Calshot Street, formerly No. 33 Southampton Street, was in 1835–7 the last residence of the clown Joseph Grimaldi (Ill. 534). By then a cripple, he was regularly taken to the Marquis of Cornwallis, a pub at the corner of Southampton Street and Collier Street, on its landlord's back, and died in the night after one such evening, 'by the visitation of God'. (fn. 46) A commemorative plaque was put on the house by the London County Council in 1938, but taken down early in 1960 when the terrace was scheduled for demolition. (fn. 47)

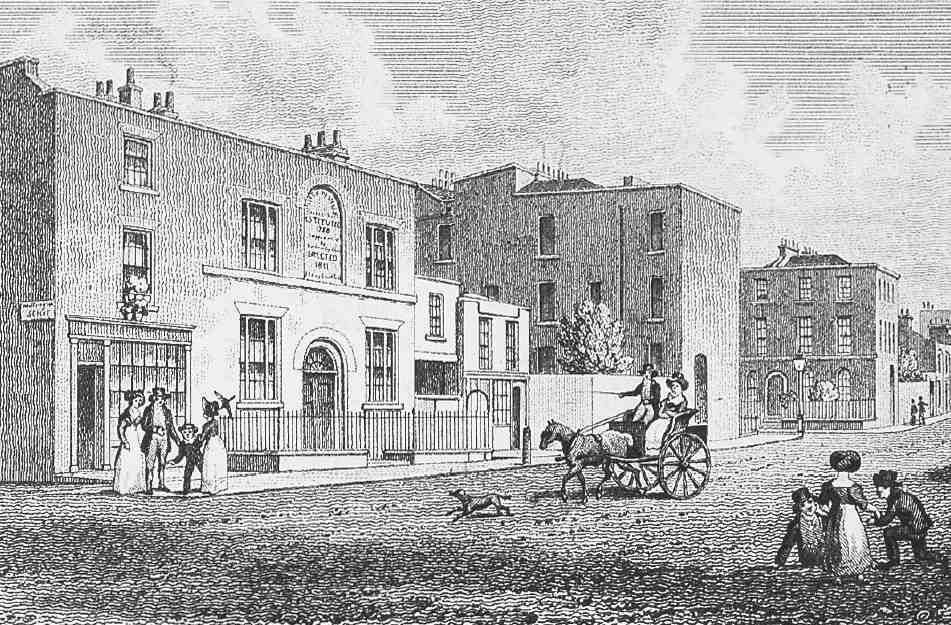

Collier Street. The line and full east—west extent of Collier Street, named after Henry Penton's man of business, Thomas Collier, had been fixed by 1787, even if its layout had not then begun. (fn. 48) It acted as an east-west crossroute and was not regarded as a focus for development, though it certainly had houses. Two early engravings (Ills 422, 536) convey its desultory character, with the corners given over to the flanks of buildings facing the north—south streets or in some cases shops or pubs. One early building of interest was the expanding Pentonville Charity School, transferred hither from Hermes Street in 1811 into purpose-built premises, with a schoolmaster's house adjacent. It stood on the north side of the street just east of the corner with the new Wellington Street. (fn. 49)

Wellington Street. No visual record appears to survive of this long cul-de-sac, renamed Busaco Street (after one of Wellington's Peninsular War triumphs) in 1890, nor are details of its construction readily available. It was cut through in about 1810–12 on part of the land assigned in 1789 to John Cumming, and packed with thirty houses (later increased to forty-four). (fn. 50) These houses were small and probably always mean. At the north end on the west side the pattern was broken by a short run of broader–fronted buildings, perhaps early tenements, with further cottages crammed in courts behind, named Wellington's Cottages or Wellington Place and Prince's Cottages or Prime's Buildings. These unusual dwellings had been replaced with more conventional terrace-houses by the 1890s. Busaco Street developed into a notorious slum whose clearance became a clarion call for Finsbury Council's inter-war rehousing policies and furnished the original name to Tecton's housing scheme of 1937. It had been totally demolished by 1940.

Calshot Street

533. East side (Nos 12–34, right to left) in 1953. All demolished

534 (left). East side looking towards Pentonville Road in 1959. Marquis of Cornwallis on corner of Collier Street at extreme left; Nos 10–34 (right to left) in centre; Pentonville Road in background. All demolished

535 (above). No. 22, last home of Joseph Grimaldi, in about 1937. Demolished

Southampton Street to North Street

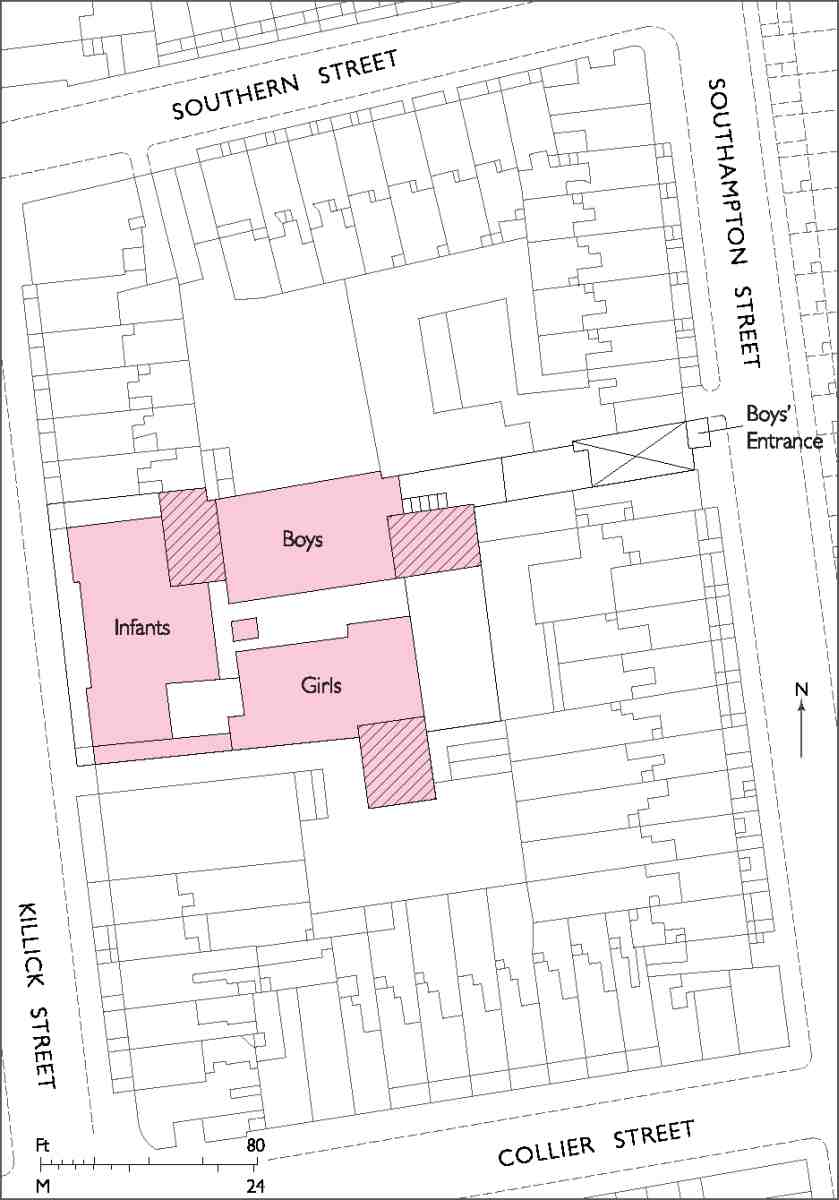

The original taker in January 1786 of the block of Penton land from Southampton Street to Winchester (now Killick) Street, the next new north—south street westwards out of the New Road, was Joshua Hodgkinson. This bricklayer-builder, sometimes described as of St Pancras and sometimes of Lewisham, was a developer of some substance, active around this time in Somers Town, and elsewhere in Clerkenwell, on the Penton estate and at Hamilton Row, Bagnigge Wells Road. Here, leases of 1786–8 suggest that Hodgkinson got on expeditiously below Collier Street. (fn. 51) In addition to houses on the streets, a small internal court was tucked within the block, named Winchester Cottages on Hornor's map of 1808 and accessible via Winchester Court, an alley off Winchester Street. This site provided the nucleus for the future Winton School. Hodgkinson or his nominees probably also built the further houses on the east side of Winchester Street north of Collier Street that appear on Horwood's map of 1799 (Ill. 528), but by then his efforts appear to have subsided, and in the next century development here took a different course.

The original arrangements for developing the Penton land west of Winchester Street to the parish boundary are obscure. It seems likely that the plan was for Hodgkinson to tackle it along with the victualler Samuel Coney, the partnership which in the 1780s built Pleasant Row fronting Pentonville Road at this point (see page 361). There is a lease of 1784 to Coney for some ground on the east side of North (now Northdown) Street. (fn. 52) But progress was slow, with only about fifteen dwellings in the street completed by the end of the century, probably including the carcase of the present No. 16, formerly the Prince of Wales pub. (fn. 53)

In 1802 Henry Penton III drew up an agreement with William Horsfall, then described as a builder of St Marylebone, but perhaps identifiable as the William Horsfall, surveyor, employed in 1778 by the Middlesex justices to survey Hicks' Hall in St John Street, alongside the county surveyor Thomas Rogers. (fn. 54) The agreement concerned the whole western corner of Penton's estate, including the block between Southampton Street and Winchester Street leased to Hodgkinson, the area between Winchester Street and the parish boundary including North Street; and in addition the far larger Penton freeholds in Islington to the west and north of this boundary, most of which was then brickfields. The whole amounted to over twenty acres and under the agreement could be developed under 99-year leases. In 1806–7 Horsfall was able to acquire the freehold (Ill. 425). (fn. 55) Why Penton should have alienated this section of his property is unknown, but the times were not favourable and his resources may have been stretched.

536. Collier Street, north side c. 1828, looking towards Cumming Street. On left, Pentonville Charity School and shop on corner of Wellington (later Busaco) Street. All demolished

Horsfall probably focused his attention on the Islington portion of his acquisition. There the advent of the Regent's Canal in 1820 allowed him to construct a large goods basin, the Horsfall (now Battlebridge) Basin, whose opening in 1825 attracted warehouses, depots and businesses and helped to commercialize the area. (fn. 56) On the Clerkenwell side his activities were very modest. In North Street only a few premises seem to have been added in the first decade of the nineteenth century. The erection before 1813 of a large brickworks for John Weston just behind Pentonville Road west of North Street may have dinted any ambitions for polite houses in the vicinity. (fn. 57)

Horsfall having died by 1825, his estate was inherited in equal portions by his daughters, Elizabeth and Charlotte. It was under Charlotte's husband, Robert McWilliam, an architect and surveyor of Furnivals Inn, that the development of North Street was pursued. (fn. 58) Little is known of the Scottish-born McWilliam. No buildings have hitherto been ascribed to him, but he was a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy, and published in 1818 a significant treatise on dry rot, dedicated to the 4th Duke of Gordon and subscribed for widely among members of the architectural profession. He became a Justice of the Peace for Middlesex towards the end of his life.

The handsome classically detailed terrace that is now Nos 27–53 Northdown Street was built in 1839 by McWilliam, who had plans in place for developing the entire estate by the time of his death in December 1842. (fn. 59) His will provided that his executors should sell the estate to provide legacies and annuities for his brother and sister in Banffshire and their offspring. (fn. 60) The Battle Bridge estate was duly sold by auction in two parts, in 1843 and 1844. (fn. 61) At that time portions of North Street and the land behind had still to be built up. The present Nos 32–46 Northdown Street date from the period after the sale. Smaller dwellings built behind the frontage around this date, notably the insalubrious North Avenue between North Street and Winchester Street, soon degenerated into slums.

537. Looking north-east into Islington from first phase of Priory Green Estate, c. 1952. In centre foreground, remains of Penton estate wall, still blocking pavement in Cumming Street (left). On extreme right, Redington House, Priory Green. Mostly demolished

Early occupants of the better houses in North Street were mostly families with one or two servants. But within ten years the census reveals a downturn in the street's social status, with many of the houses in multi-occupancy, and few servants. (fn. 62)

Victorian Reconstruction

Pentonville's social decline and creeping industrialization were palpable by the 1850s. But little could be done to address the changed conditions until the original long leases fell in from the 1870s onwards. The Victorian history of the area west of Penton Street is therefore broadly one of stagnation up to about 1870, followed by a cluster of initiatives motivated by a combination of economic advantage and social purpose.

A symbol of the changing character of the area west of Penton Street was a high wall along part of the northern boundary of the Penton estate. This is likely to have been built when the area to the north was first built up in the 1820s, with what were then no doubt less select streets than those of Pentonville. Penton Street had probably always been sealed off at its north end with a fence and gate, and in 1828 the Penton Estate receiver, William Vokes, recorded trouble with trespassers passing through a gap there, and an incident in which the fence was broken down to let the fire-engine get to a chimney-fire. (fn. 63) The wall extended from at least as far east as the site of Hermes Hill House to the western edge of the estate at Southampton Street, cutting off the north ends of Rodney and Cumming Streets from Rodney Street North and Cumming Street North. (fn. 64) In 1881 Captain Penton's agent, James Gibson, reported that the boundary wall in Cumming Street, repaired some ten or twelve years earlier under J. B. Watson's supervision, had been damaged by a gale and needed repairs, 'as the children are making their way through, and the wire work has completely disappeared'. (fn. 65)

By this date the wall must have represented a futile rearguard action against the social changes affecting the estate and the depreciation of property there. Ten years later, probably as a result of objections by the new London County Council, which secured an Act of Parliament for the removal of gates and bars in various London streets in 1890, (fn. 66) the roadways of Cumming and Rodney Streets were opened up to their northern continuations. However, reluctance to demolish the wall is evident, as part of it still blocked the pavement in Cumming Street until the wholesale redevelopments after the Second World War (Ill. 537).

As most of the buildings mentioned in this section have been destroyed, it is organized thematically. Fuller accounts of the few buildings that survive appear in the final section of the chapter.

Housing

Significant housing redevelopment took place in the 1870s and 80s, as leases expired, in the form of traditional houses and tenements alike. Only one scheme affected the street layout. This was Affleck Street (1884–5), an addition to the Pentonville grid sandwiched between Calshot Street and Cumming Street on the site of the London Female Penitentiary, and consisting mainly of flats or tenements. Since the few remains of Affleck Street face Pentonville Road, the reader is referred to the account of that road for further details (page 360).

Pentonville's earliest purpose-built tenements, like those in Affleck Street, were all private speculations. The first appeared during the 1870s in the Hermes Hill—John Street area, and are described in further detail below (Hermes Street dwellings; Penton and Rodney Residences). In addition, John Street (Risinghill Street from 1880) and Rodney Street acquired further new dwellings. On the south side, four new houses were built west of Hermes Street (Benjamin Carpenter, builder, 1871); five houses known as Royal Terrace east of Hermes Street (William Royal, 1879); and three small tenements west of Carpenter's houses (William Walton, undertaker, 1879). (fn. 67) Five further new houses designed in 1879 by the Penton estate surveyor, T. H. Watson, were probably on the north side, where Risinghill Street School was also built soon afterwards. (fn. 68) In Rodney Street, piecemeal rebuildings took place between about 1880 and 1886 under the auspices of the builder A. G. Allard with help from the architect J. Laws. Some of this involved reconditioning old houses, but much was new work. It included the rebuilding of the Rodney's Head pub at the corner with Henry (Donegal) Street, and what seems to have been a substantial five-storey block with bay windows running south from the corner with Collier Street, very likely occupied as tenements. (fn. 69)

The efforts of the major philanthropic dwelling companies in building model dwellings in Pentonville were confined to a pair of blocks erected further west in 1894–5, Winton Houses in Killick (Winchester) Street and the surviving Pollard Houses in Northdown (North) Street, also separately discussed below.

All the buildings in the vicinity of Risinghill Street mentioned above and below were either badly damaged in the Second World War or in an area already then scheduled for clearance. Their sites are now covered by the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School.

Model dwellings, Hermes Street. This small speculative venture was initiated by Thomas Flight, perhaps Victorian London's most notorious 'slumlord', who was said at one time to control as many as 18,000 houses. (fn. 70) It shows that Flight sometimes built new tenements as well as taking over existing houses.

In 1868 Flight obtained a lease of two substantial properties on the west side of Hermes Street, one of which was still then in use as part of the Pentonville charity school (page 408), as well as an adjacent row on the north side of Henry Street. A first plan to demolish the Hermes Street houses and replace them with two semi-detached pairs, with further pairs of houses behind, was rejected by the Metropolitan Board of Works. (fn. 71)

Flight therefore decided instead to replace the two houses with two blocks of model dwellings. The new scheme, as presumably also the original one, was designed by Banister Fletcher, Flight's house-surveyor, and illustrated in his Model Homes for the Industrial Classes (1871). The first block was erected in 1870, and in his book Fletcher speaks of these dwellings as having 'answered extremely well, no difficulty having been experienced in letting every set of apartments on remunerative terms'. (fn. 72) The second, adjacent block seems to have been built in 1880–1, after Flight's death. (fn. 73) The deep-plan tenements appeared from the road like a pair of plain, two-storey, double-fronted houses (Ill. 538). Each flat consisted of a living-room, scullery, two bedrooms and a WC. A feature of the planning was that the second bedroom was only accessible from a rather poorly lit common hallway (shared by the occupants of four flats). This was done on the assumption that it was likely to be occupied by a lodger. On the ground floor the WCs were out in a yard, but those upstairs opened off the scullery.

Penton and Rodney Residences. These contiguous tenement blocks occupied the site of the houses and gardens at the top end of Rodney Street on the east side. They were built in 1878–9 for the Sanitary Dwellings Co. Ltd, which had been set up by Banister Fletcher and others in 1876 and for which he acted as architect and surveyor. They resembled Fletcher's earlier Hermes Street dwellings begun for Thomas Flight, being mostly of similar footprint to those buildings, but of four storeys. The apartments at Rodney Residences included a washroom, but at Penton Residences timber wash-houses were provided on the roof. (fn. 74)

Rodney Residences made up a row of three blocks with their entrances facing Rodney Street: back to back with these stood three of the Penton Residences blocks, which were reached from a passage on the north side of John (Risinghill) Street. Four more blocks, of slightly variant shape and size, occupied two sides of a courtyard east of these. (fn. 75)

If the aspiring name 'Residences' was chosen to match the character of the intended tenants it does not seem to have been successful in the long term. By 1894 the owner was recorded as W. Prichard, a solicitor in Bedford Row, though he may only have been acting as agent for new owners. At all events, it was Prichard's firm which complained to the Penton Estate in 1909 that there had been 'considerable difficulty' in letting flats there, 'and in fact respectable people cannot be got to take the rooms'. This was blamed on the dilapidated state of neighbouring houses, and more particularly on the use by prostitutes of houses immediately opposite, on the south side of Risinghill Street. (fn. 76)

538. Model dwellings, Hermes Street, street elevation and plans. Banister Fletcher, architect. Left half built in 1870, right half probably in 1880–1. Demolished

539. Winton Houses, Winchester (now Killick) Street, in 1898. Davis & Emmanuel, architects, for the East End Dwellings Co., 1894–5. Demolished

Winton Houses and Pollard Houses. These two blocks, standing almost but not quite back to back on Killick Street and Northdown Street, were erected simultaneously in 1894–5 by the East End Dwellings Co., to the designs of their regular architects, Davis & Emmanuel, with S. J. Jerrard as builder. (fn. 77) Large-scale walk-up flats on five storeys, they represented a swansong for the model dwellings movement at a time when flatted housing was changing under the auspices of the London County Council. In appearance they mitigated the austerity of the older blocks with a lively roofline sporting turrets and occasional gables. On Pollard Houses, the standard stock bricks were relieved by friendlier red dressings. Winton Houses, now demolished, seems to have been a touch plainer (Ill. 539).

Winton Houses occupied the larger and more open of the two sites, where Stuart Mill House now stands. Its outline plan was U-shaped, with slightly projecting open staircases in the centres of each of the three sides of the court. Pollard Houses consisted of two parallel blocks, one facing North (now Northdown) Street, the other in a court behind. Both buildings were badly damaged by bombing in 1944, after which Winton Houses was demolished but Pollard Houses was deemed in good enough condition to be repaired.

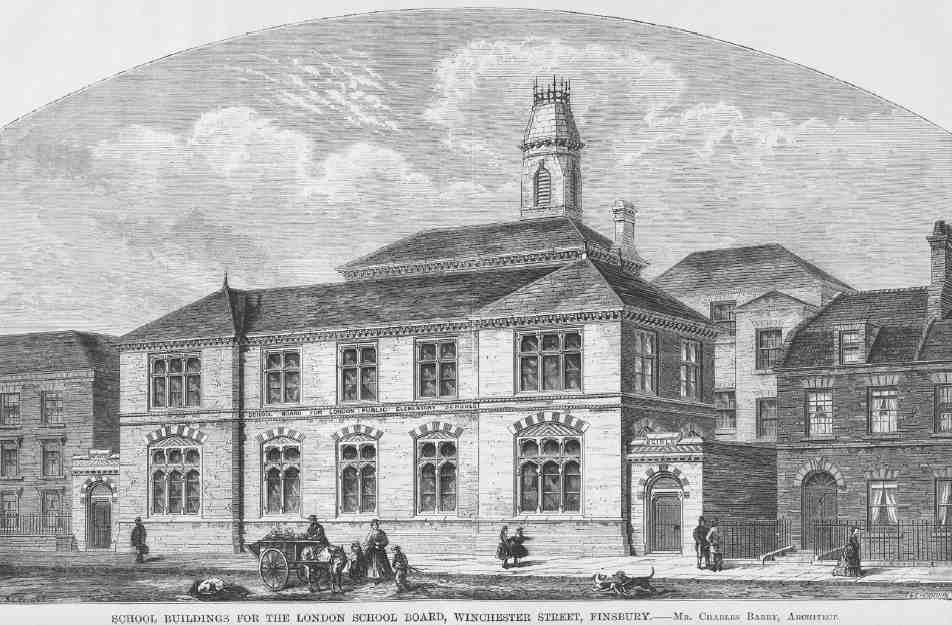

Schools, chapels and social institutions

Pentonville's two existing schools date back to the era of Victorian improvement. Originally board schools, Winchester Street School (1872–3) and Risinghill Street School (1884) have both expanded to envelop the urban block in whose midst they were at first tightly implanted. Winchester Street School is now Winton School, Killick Street, while Risinghill Street School has become the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School, a comprehensive that today hogs two whole former Penton estate gridrectangles. As major presences in the area today, they are dealt with in detail below (pages 419–21, 432–5).

Various more ephemeral schools and clubs also sprang up in this period, a minority in purpose-built premises. The main church school was the Pentonville Charity School, sometimes later known as St James's Pentonville Schools. The boys' school on the north side of Collier Street was reported in 1871 as 'in a most deplorable condition', with a shortage of books for the younger pupils. The girls' and infants' department, in which instruction was also condemned as 'far from efficient', was just then being rebuilt on the opposite side of Collier Street at the back of the long strip of graveyard behind Pentonville Chapel. The new building, designed by Habershon & Brock and built by C. Wood of Highgate, was in a stripy brick Gothic style, with two floors of schoolrooms over a covered playground. (fn. 78) In 1887 the boys' school was augmented by a mission hall, the Stubbs Memorial Hall, said to have been converted from a factory. (fn. 79)

Among the slew of foundations trying to lift Pentonville from its slough between 1880 and 1914 were the North London Working Men's Club in Rodney Street; the 'entirely unsectarian' (fn. 80) Red White and Blue Christian Institute for Lads in Cumming Street, which besides its other efforts sent women, girls and boys ('of the very poor and rough class') on seaside holidays; a Christian Israelites meeting-house in Hermes Street; and the Howard Institute for Women in Cynthia Street. (fn. 81) The London Female Penitentiary in Pentonville Road was a major institutional presence from the early nineteenth century until its departure to Stoke Newington in the 1880s.

In general, the main nonconformist churches were poorly represented in Pentonville, in part perhaps because of opposition from the Penton Estate. A Methodist chapel built on the east side of Winchester (Killick) Street after 1875 (not on Penton ground) was short-lived, succumbing to the expansion of the Winchester Street School around 1910.

Public houses were naturally concentrated along Pentonville Road, but even in the streets to the north the effects of the late Victorian pub-building boom were felt. The Rodney's Head at the north corner of Rodney Street and Henry Street was rebuilt in 1885–6 (J. Laws, architect), (fn. 82) and, to judge from its appearance, the Marquis of Cornwallis at the south-east corner of Southampton Street and Collier Street was also rebuilt (Ill. 535).

Industry

As elsewhere in Clerkenwell, this part of Pentonville never lacked house-based craft industries. In Hermes Street, one of the minor and probably poorer streets, the following trades are represented in the directories for the 1880s: bricklayer, builder, camera maker, carpenter, copperplate maker, cowkeeper, endorsing press maker, painter, tailor, telegraph instrument maker, timber merchant and waterproof maker. Most of these probably operated from home or from their yards behind. (fn. 83)

A shift toward larger, purpose-built premises can be seen after 1870. At first most of the larger works were on or immediately behind Pentonville Road, with a few exceptions like a large 'wheel and axle works' on the north side of John (Risinghill) Street, installed or enlarged in 1862. (fn. 84) But by 1894 there were substantial works behind both sides of Risinghill Street and off Rodney Street, Cumming Street and Southampton (Calshot) Street. By 1938 the biggest of the Pentonville Road enterprises, Lilley & Skinner's boot and shoe warehouse, had reached right back to Collier Street, south of which much of the old housing was given over to commercial uses of one kind or another. (fn. 85)

A few remnants of old industrial premises survive, largely in Pentonville's westernmost streets. They include the large factory-warehouse at Nos 61–71 Collier Street, built in 1905 for blacking manufacturers. (fn. 86)

Existing Buildings

Up until the Second World War the pattern of wide streets lined by low, drab and ageing buildings still obtained for most of the area. Nevertheless between Pentonville Road and the line of Collier Street and Donegal Street, industry was the strongest force. North of that line there still stood mostly decrepit housing in multi-occupation, but much-longed-for municipal activity in slum clearance had begun. It was a decade before Grimaldi House (1926–7), its harbinger at the top of Calshot Street, was joined by the London County Council's Bonington House on the North Avenue slum site. But from 1937 Finsbury Council had been nurturing grand plans, having called in Tecton to clear Busaco Street and everything around it and substitute an exemplary display of high modern flats for a resurgent Pentonville working class. When war was declared, almost the whole block bounded by Calshot, Collier, Cumming and Grimaldi Streets had been flattened (Ill. 545). The Council was gearing up to tackle also a second large clearance area south of Wynford Road, on either side of Rodney Street.

Western Pentonville is a textbook example of an area where wartime bombing facilitated the kind of comprehensive redevelopment that architect-planners had dreamt of but could hardly have hoped to realize on such a scale. Even though the bombing hit the district harder than some others, particularly around Risinghill Street and the south end of Killick Street, much of the damage consisted simply in rendering outworn properties frailer and more expendable.

With the Penton Estate itself in its last throes as a body, imposing a new shape upon this unloved area fell to Finsbury Council, seconded (though sometimes checked) by the LCC. Priory Green (1948–58), as the reconfigured and expanded Tecton design for Busaco Street became after the war, announced the vision for the new Pentonville, turning away from the street in all its arrogant magnificence to invoke, so it was hoped, a fresh local pattern of community, pride and culture. But the underlying problems of the area could not be solved by building alone, and the estate was not a social success. The LCC's Risinghill School (1957–60), also inward-looking and occupying two whole former blocks, encountered similar problems more dramatically. By the time of its embarrassing closure in 1965, the years of post-war idealism were on the wane. When Islington came to build housing in succession to Finsbury, it was more cautious, though on the Priors Estate of 1970–4 it had not yet abandoned the ideal of self-containment and inwardness. While solving urgent problems of security, the railing-in and privatization of the main estates since the 1990s has done nothing to dispel the image of turning away from the street.

So far has the tide of municipal power now ebbed that Islington Council has today ceased not only to build but even to manage the huge portfolio of housing it once held in this area, though it runs a neighbourhood office in Calshot Street. Some new homes have been added by housing associations and the like, especially in the western sector. But the main impetus in the past thirty years has come from commercial interests which have replaced the old sites of productive industry north of Pentonville Road with a series of, on the whole, fairly colourless office and studio buildings. Only on the Pentonville Road—Killick Street—Collier Street—Calshot Street block has commerce tried to impose the kind of full-block redevelopment which the municipal planners once favoured, with the Chapman Taylor development for Sterling Properties begun in 1973 (see page 364); it has proved no more successful. Most architecture since that period, aesthetically ambitious or not, has confined itself to small-scale initiatives, insignificant compared to the infrastructural and social upheavals of 1945–75.

The following account of the buildings proceeds roughly from east to west, in three main sections divided by the lines of Rodney Street and Calshot Street. Joseph Grimaldi Park is dealt with in the context of the demolished church of St James, Pentonville, in Chapter XIV.

Risinghill, Donegal and Cynthia Streets Area

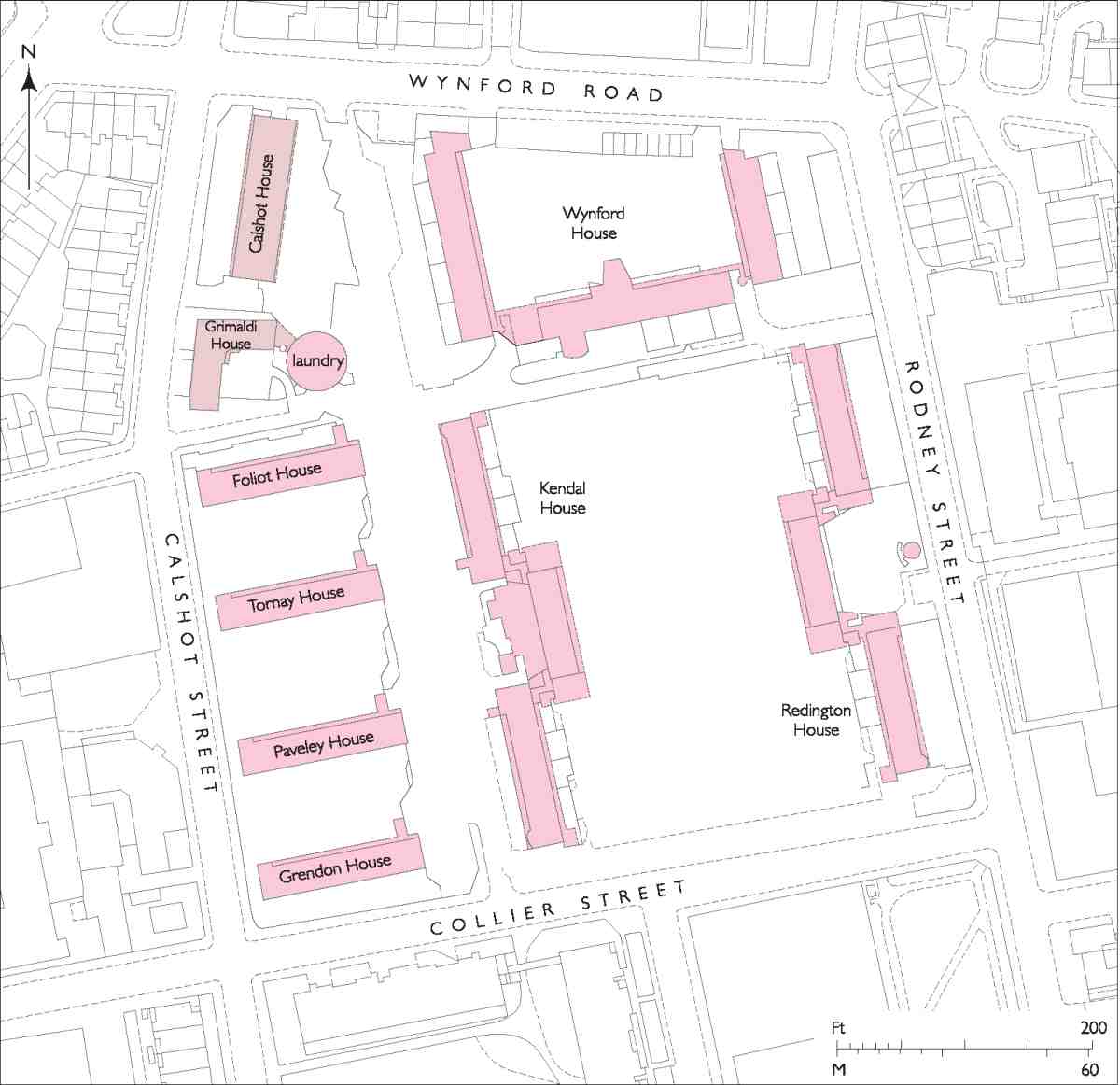

Wynford Estate

This small housing estate occupies a tight site wedged between the back of St Silas's Church and the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School, running up to Wynford Road on the north. It was built to the designs of Westwood, Piet, Poole & Smart for the Greater London Council about 1973–5, and comprises three brick blocks of flats and maisonettes varying in height from three to five storeys. The blocks are aligned east—west, in approximate parallel. The northernmost and longest, sited at the eastern end of Wynford Road, has balcony-access flats numbered 94–164 in that road. Vehicular access through a tunnel in its centre leads to the blocks behind, Nos 1–12 and 14–27 Chalbury Walk. These are sited away from street frontages and accessible also from a secondary pedestrian entrance from Risinghill Street.

The original accommodation consisted of two-person units with five- and six-person maisonettes above. In reviewing the estate, the Architects' Journal criticized the quality of the brickwork, the use of tile-hanging, and the proportions and detailing of the windows, blaming these defects largely on the 'incompatibility of brief, site conditions and restrictions of the cost yardstick'. (fn. 87) The Wynford Estate passed from the GLC to Islington Council, and in 2000 was one of the estates taken over from Islington by the Peabody Trust under the King's Cross Ten scheme.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School (formerly Risinghill School)

In educational history Risinghill is synonymous with a crisis in secondary teaching styles that erupted here in 1965, leading to the closure of the school of that name. Since then this diffusely planned school has twice changed its title. Most of its blocks were designed by the Architects' Co-Partnership and date from 1957–60. But among them remains the old Risinghill Street board school, built between 1884 and 1899 (Ill. 540).

As now, that original school occupied a boxed-in site away from the street frontage, where a wheel and axle works had stood. First planned in 1882–3 to the designs of the School Board for London's architect E. R. Robson, (fn. 88) it had the three storeys typical for its date, with classrooms ranged around assembly halls on each of the floors. The first portion, erected by the builder S. J. Jerrard in 1884–5, catered for 1,200 pupils and could be reached only from a gap between houses on the north side of the street. (fn. 89) In 1898–9 the south end of the building was completed by G. S. S. Williams & Son with classrooms for some 300 further pupils, opening up the access but entailing the demolition of several houses. (fn. 90) To judge from inspectors' reports, the school in its elementary years grappled manfully with Pentonville's endemic poverty and overcrowding. (fn. 91)

Risinghill Street was gravely damaged by Second World War bombing, though the school was less affected than the surrounding houses and kept in use. The drab render which covers its brickwork and the shearing-off of the building's north end may both date back to that period. A small concrete Orlit house for the schoolkeeper was built next to its south end in 1949, and survives. (fn. 92)

In 1947 the London County Council earmarked the area for one of the large new mixed secondary comprehensive schools proposed under its London School Plan. When the project came forward in 1955, it was agreed to plan for 1,700 places on the difficult sloping site instead of the 2,000 then thought ideal for comprehensives, and to buy only part of the land, building for 1,250 in the first instance. (fn. 93) Nevertheless the plan entailed the clearing of almost two complete urban blocks down to the north side of Donegal Street and the east side of Rodney Street, and thus the obliteration of the western two-thirds of Risinghill Street and the northern end of Hermes Street.

The school's design was assigned to the Architects' CoPartnership, a firm with ample experience of post-war school building (partner in charge, Kenneth Capon); (fn. 94) Ove Arup & Partners were their consulting engineers. At that date the LCC was experimenting with various arrangements for the novel type of the comprehensive school, some by their own architects, others farmed out to private firms. At Risinghill the advice of the Ministry of Education (which the LCC did not always heed) was followed. The plan was broken down into discrete elements and a house-system instigated, whereby pupils throughout the age-range shared social space in groupings of moderate size. Most of the 'houserooms' were consigned to the old building, which was replanned for the purpose. The rest of the accommodation was split between three larger blocks nearer Donegal Street, for teaching, assembly and gymnasia, and four smaller ones to the north-west for science and crafts.

Advantage was taken of the sloping site in grouping the elements, and playpitches were interspersed between them. In the architects' minds, the larger blocks were reminiscent of Islington squares. (fn. 95) The new buildings, erected in 1957–60 with J. M. Hills & Sons as general contractors, rose to no more than three storeys. The teaching block is a concrete-framed structure with generous corridors and stairs round an open court; the assembly block, visible from the surviving stub of Risinghill Street, is steelframed; while the three gymnasia at the corner of Donegal and Rodney Streets are fronted in handsome brickwork (Ill. 541). (fn. 96)

Amalgamating four previous secondary schools, Risinghill opened in May 1960 with 1,200 children under the headmastership of Michael Duane (Ill. 542). (fn. 97) Practical subjects were emphasized in the curriculum, including courses in engineering, instrument-making, dressmaking and commerce. 'We shall watch with interest as these plans unfold and children receive the benefit their parents never dreamed of when they were at school', remarked the parish priest of neighbouring St Silas's. (fn. 98) In the event the rebuilt school underwent a turbulent early history. Duane proved a charismatic head, but his liberal attitude to discipline (in an area described by one journalist as having 'some of the worst slums, brothels, and clubs in North London') led to rifts with his staff, falling rolls and official concern. (fn. 99) By January 1965 the school was 'bordering on social collapse', with many children on probation or in juvenile courts, numerous incidents of vandalism, violence and petty arson and one attempt at a mass break-out. According to one of the teachers, Terence Constable, 'Duane's publicity work, in an attempt to get support from outside, seemed a major cause of the continuing excitement among the children'. (fn. 100)

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School, Risinghill Street

540. Looking east from Rodney Street in 2006. In background, former Risinghill Street Board School

541. Gymnasia at corner of Rodney and Donegal Streets in 2007

542. Headmaster Michael Duane welcomes pupils to the new Risinghill School, 4 March 1960. Houses on the south side of Donegal Street behind (demolished)

The LCC therefore decided to shut Risinghill and redeploy Duane, under the guise of rearranging school accommodation in the area. National publicity ensued, while schoolchildren marched through the streets demanding Duane's reinstatement. That did not take place: instead, the school was reinvented as Starcross School for Girls and opened under new management in September 1965. (fn. 101) The controversy was rekindled three years later when Leila Berg published her Risinghill: Death of a Comprehensive School. The book depicted Duane as a hero grappling with social and psychological deprivation, and placed part of the blame on the 'graceless and stark' buildings. Among others, Constable disputed this reading: 'The building was good enough, anyway, to win an architectural award'. (fn. 102) Even if the loose, liberal planning abetted Risinghill's woes, more important was the abrupt amalgamation of four schools into one, which helped to create a gang culture. (fn. 103)

In 1985 Starcross School was merged with Barnsbury School to form Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School for Girls, named after the women's rights campaigner and first female member of the School Board for London. (fn. 104) The one significant addition to the 1950s buildings has been 'Platform 1', a concrete block part-clad in slate-coloured fibre-cement board, inserted east of the teaching block facing Donegal Street, designed by Gollifer Langston Architects and opened in 2003. A detached nursery with curving geometries and polycarbonate facings stands in front. The brief allowed for community access under a 'city learning centre programme', with linguistic skills in mind both for children and adults, since 'more than 57 languages are spoken within the school'. (fn. 105) In 2006 the adult facility closed and its space was subsumed into school accommodation. A press article in that year depicted a school struggling valiantly against a poor image in the local community, not unlike its predecessors. (fn. 106)

Prospect, Rodney and Penton Houses

These three blocks of council flats, of disparate size, were built for Finsbury Borough Council in 1962–5 by Pitchers Ltd, to the designs of Emberton, Franck & Tardrew. They make up what was known until recently as the O. M. Richards Estate, after Owen Richards, a Finsbury councillor.

Plans for clearing and redeveloping the tired and wardamaged district south of Donegal Street came forward in 1957. Finsbury's first thought had been to tackle a small patch next to Cynthia Street, but in that year its Housing Committee's appetite expanded to an area bounded on the west by Rodney Street and including most of Cynthia Street and Hermes Street, with southern and eastern boundaries largely defined by the backs of properties in Pentonville Road and Penton Street. The implications were to abolish all but the southernmost part of Hermes Street, already curtailed by the Risinghill School project to the north. In July 1960 Finsbury finally obtained a compulsory purchase order. Negotiations over detail ensued with the Cockington Trust, freeholders of most of the property in succession to the Penton Estate. (fn. 107)

543. Rodney House (foreground) and Prospect House (rear), O. M. Richards Estate, Donegal Street, in 2006. Emberton, Franck & Tardrew, architects, 1962–5

Emberton, Franck & Tardrew, already engaged on other work for Finsbury, had meanwhile been confirmed as architects. (fn. 108) In March 1961 they produced plans for two blocks: one of three storeys running along Donegal Street (Rodney House), and one of eight or nine higher up the hill (Prospect House). After an attempt to spatchcock two extra small blocks on the eastern part of the site, it was decided to add only a single, two-storey block of balconyaccess flats (Penton House), set back south of Prospect House. As built, Prospect House rose to ten storeys, Rodney House to four (Ill. 543). (fn. 109)

With C. L. Franck's drive and the help of Felix J. Samuely & Partners, the architects' usual consulting engineers, for the foundations and concrete frames, the estate seems to have been efficiently worked out and built in 1962–5, despite early delays from severe weather. The ceremonial opening of Prospect House in January 1965 was Finsbury Council's final public act before its absorption into Islington. (fn. 110) The first intended name was the Donegal Estate; that of O. M. Richards was substituted just before the opening. (fn. 111)

Alone among Emberton, Franck & Tardrew's undertakings for Finsbury, this estate was not published. Some of its detailing, though not its planning, followed their larger King Square Estate in Finsbury, started shortly before. The fronts are clad in precast concrete panels and grey bricks, not improved by later over-painting and changes to the windows. Rodney House is marked by hefty refuse-chutes that rise up to the roof through the three external balconies facing Donegal Street. Prospect House, the squarish point block near the top of the hill, originally had an open base, and still retains the curved roof over the drying area on top—a reminder of the earlier Tecton housing in Finsbury on which Franck had worked. Its ground floor was enclosed when entryphones and other security features were installed on the estate by Hutchinson & Partners in 1984. The fencing round the blocks dates from about 1993. (fn. 112)

Other buildings

Until about 1930 the firm of Dunn & Hewett had an extensive cocoa and chocolate factory between Cynthia Street and Rodney Street, which grew from the firm's original premises at Nos 130–134 Pentonville Road (see page 354). Two buildings surviving from the works are Nos 4–10 Rodney Street and 6–9 Cynthia Street.

The Rodney Street building is a plain five-storey warehouse, set back from the street and abutting on to the back of Nos 136–150 Pentonville Road. It is dated 1915. Now in studio-office use, it has a chic extension of c. 1997 at the north end, clad in aluminium and glass. (fn. 113)

Nos 6–9 Cynthia Street represent an extension of the 1880s and 90s, eight and a half bays wide with a goods entrance near the north end. In 1985 this building was made into four self-contained light-industrial units by CZWG Architects for SG Consulting Ltd, with Hayden Blake as builders. More recently, it has been converted to media-related uses as part of a 'Centre for Media Excellence'. (fn. 114) On the front of the building is a probably re-used stone tablet inscribed with a tag from Psalms, except the lord keep the city the watchman waketh but in vain.

Adjoining, Nos 3–5 Cynthia Street is a three-storey building with a ground-floor workshop and a maisonette flat above set back behind a garden-terrace. It was built in 1994–5 as the Flower House, to the designs of Peter Romaniuk, architect, for his wife, Paula Pryke, florist to celebrities. (fn. 115) The workshop is steel-framed, with sliding glass-block screens across the whole front.

544. Grimaldi House, Calshot Street, in 2006. E. C. P. Monson, architect, for Finsbury Borough Council, 1926–7

545. Busaco Street clearance area, c. 1939. In background, west side of Calshot Street (demolished) and Grimaldi House (right)

546. Priory Green Estate looking north from Collier Street in 2007

Between Rodney and Calshot Streets

Grimaldi House, Calshot Street

The origins of the clearance and reconstruction project that led to the rebuilding of the whole quadrilateral bounded by Collier Street, Calshot Street, Wynford Road and Rodney Street, the disappearance of Busaco Street and Grimaldi Street, and the removal of the northern half of Cumming Street, go back to October 1924. Just then Finsbury Borough Council was actively looking for sites to build its own housing for the first time, when its attention was drawn to slum properties at Nos 88–94 Southampton Street and No. 1a Grimaldi Street—on ground (belonging to the Thornhill Estate) north of the old parish boundary, which had been designated part of Finsbury on the creation of the Metropolitan Boroughs in 1900. The council's Medical Officer of Health duly declared the properties unfit, prompting a closing order, and in February 1926 the council agreed to buy them. (fn. 116)

Grimaldi House, the modest block of municipal tenements built on these sites, represented Finsbury's pioneering effort in municipal housing. A larger scheme at Mandeville Houses, Mantell Street, was projected a fraction earlier but completed later (page 403). The rebuilding was entrusted to the architect E. C. P. Monson, whose plans were promptly carried out in 1926–7 by Canonbury Construction Ltd. Dwarfed today by its neighbour, Priory Green, the block is five storeys in height and L-shaped in plan. Its main external fronts are of plain red brick with neo-Georgian sash windows (Ills 544, 545). Access to the upper flats is by an internal stair at the rear of the building and by external balconies. The accommodation was generous for its day, with a separate scullery, bathroom and toilet for each of the original fifteen flats. (fn. 117)

Grimaldi House was less than a decade old when Lubetkin and Tecton first planned their adjacent Busaco Street housing scheme. In some early designs for this project it abutted directly against the new blocks, to which it offered a strange contrast. Doubtless the Tecton architects would have preferred to remove it, but it was too useful and recent for that. A real threat of demolition first arose in the late 1970s. The block was refurbished to provide flats for single people but not finally reprieved until 1986. (fn. 118) Grimaldi House is now owned and managed by the Peabody Trust together with the Priory Green Estate.

Priory Green Estate

Priory Green is the most grandly conceived of the three arresting housing estates designed under Berthold Lubetkin for Finsbury (Ill. 546). Its genesis was long and tortuous. Clearance of slums at the core of the site had been anticipated well before Tecton were appointed architects in 1937. Even so, building started only in 1948, after many modifications and a major enlargement that shifted the estate's centre of gravity, and did not finish until 1958. Its subsequent history has not been easy.

The Grimaldi House project drew Finsbury Council's attention to the wider urgency of improving housing in this part of Pentonville. Broader horizons seemed to dawn when the Housing Act of 1930 offered incentives for slum clearance. The Labour administration, then in its first term of power on the Council (1928–31), identified six areas for action. One was Busaco Street, the deep and fetid cul-de-sac running north off Collier Street which gave this housing scheme its original name. In effect it was a shorthand for a complete urban block packed with almost a thousand people, bounded by Grimaldi Street to the north, Southampton Street to the west and Cumming Street to the east. A study of Busaco Street was commissioned from the Medical Officer of Health, and the Penton Estate agreed to sell the property. But the financial stringency of these years dashed hopes of progress. (fn. 119)

In 1935 a fresh Housing Act directed authorities to survey and tackle overcrowding. Coinciding with the advent of Finsbury's second Labour administration under Harold Riley's leadership, this breathed fresh life into the scheme. Finsbury's survey identified Pentonville as the borough's worst district for overcrowding and refocused attention on Busaco Street. (fn. 120) Meanwhile Riley's chief ally of the time, Dr Katial, then vice-chairman of the Housing Committee, had commissioned Lubetkin and Tecton to design the Finsbury Health Centre. The two were soon discussing the possibilities for collaborating on housing (page 16). Brief notes of October 1936 moot Tecton's involvement in a proposed housing site at Southampton Street. (fn. 121) They were formally involved at Busaco Street by the following spring, producing their first designs soon after. (fn. 122)

For Lubetkin and his firm, Busaco Street offered the chance to test and advance a design methodology they had propounded in 1935, when they won a competition for working men's flats promoted by the Cement Marketing Co. (fn. 123) Tecton's proposal was for slabs aligned in strict parallel, following the so-called Zeilenbau site-layout prevalent in Weimar Germany and lately publicized in Britain. The design championed generous flats off staircases instead of access galleries, and fuller services than such dwellings usually enjoyed. It also drew on Tecton's experience at their Highpoint One flats in Highgate (1933–5) by advocating a concrete structure with solid external walls raised with sliding shuttering, developed by Ove Arup. This, they argued, would save enough to allow better accommodation and services.

The 1935 competition had asked only for five-storey flats without lifts. Since Finsbury was obliged to rehouse all those it displaced and had few alternative sites at its disposal, it followed that Busaco Street needed to be denser, calling for higher flats with lifts. Despite modernist clamour, few working-class flats in high slabs served by lifts had as yet been built. The chief precedent was a single nine-storey slab with balcony access on the Bergpolder development, Rotterdam (1933–4). The more monumental of the urban working-class estates built in 1920s Vienna like the Karl Marx-Hof, rising in parts to seven storeys, also had a few lifts.

From start to finish, Tecton's plans for the estate maintained the parti of two grand parallel blocks running north-south, facing on to an ample central garden open towards Collier Street at the south end, with a separate block commanding the north end of the site. It was the architects' evident original intention to create the image of a working-class stronghold. As first designed, the main blocks would have been over 400 ft long—not quite unprecedented, as the Karl Marx-Hof and its London derivative, Levita House of 1930–1 on the London County Council's Ossulston Estate in Somers Town, had been longer.