Pages 239-263

Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying and sponsored by English Heritage. All rights reserved.

In this section

CHAPTER X. Wilmington Square Area

The area described in this chapter, centred on Wilmington Square, lies between Amwell Street and Farringdon Road to the east and west, and Lloyd Baker Street and Rosebery Avenue to the north and south (Ill. 315). It covers the greater part of Spa Field, more commonly Spa Fields, which gained fame shortly after the Napoleonic Wars as the site of great assemblies in support of universal suffrage. That was on the eve of its development. In modern terms, the rallying-ground of 1816 was the area north of Exmouth Market, but the term Spa Fields also applied to the area between there and Bowling Green Lane, which had been extensively built up many years earlier and included the London Spaw or Spa from which the name derived. The whole of the ground comprised the western of the two Clerkenwell estates owned by the Earls, later Marquesses, of Northampton between the seventeenth century and the mid-twentieth century. (The other, Woods Close, is described in volume xlvi of the Survey of London.) Rosebery Avenue, which cut through the estate in the 1890s, is taken as the southern boundary here. The southern part of Spa Fields, including Exmouth Market, is dealt with in Chapter II.

The northern portion, something above sixteen acres in extent, was bisected diagonally by footpaths and also crossed by water pipes from New River Head. It was systematically built on from 1817 into the 1830s, the better houses around Wilmington Square giving way to lesser buildings in small streets and courts on the peripheries (Ill. 316). By mid-century much of the square was given over to manufacturing and the streets had become slums. The Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes intervened in the 1880s, and in the 1890s Rosebery Avenue cut a swathe through some of this impoverished neighbourhood. To the south-west and north there was redevelopment in the 1920s and early 1930s: by the Northampton Estate for industry and commerce, especially on Easton Street; by Finsbury Council for public housing (the Margery Street Estate) and baths; and by the Metropolitan Police, for married-quarters (Charles Rowan House). Some of this has been replaced again since 1990. Wilmington Square has remained intact apart from some conservative rebuilding.

Discussion of aspects of the area's early history and a chronological outline of development and redevelopment are followed by accounts of individual streets and buildings. Wilmington Square and its environs south of Margery Street are dealt with first, followed by the comprehensively rebuilt area to the north.

314. Spa Fields in the 1790s: a recreation of 1857 by Charles Matthews, looking east from Bagnigge Wells Road to Merlin's Cave at the top of the hill. To the left, the Spa Fields Cake House

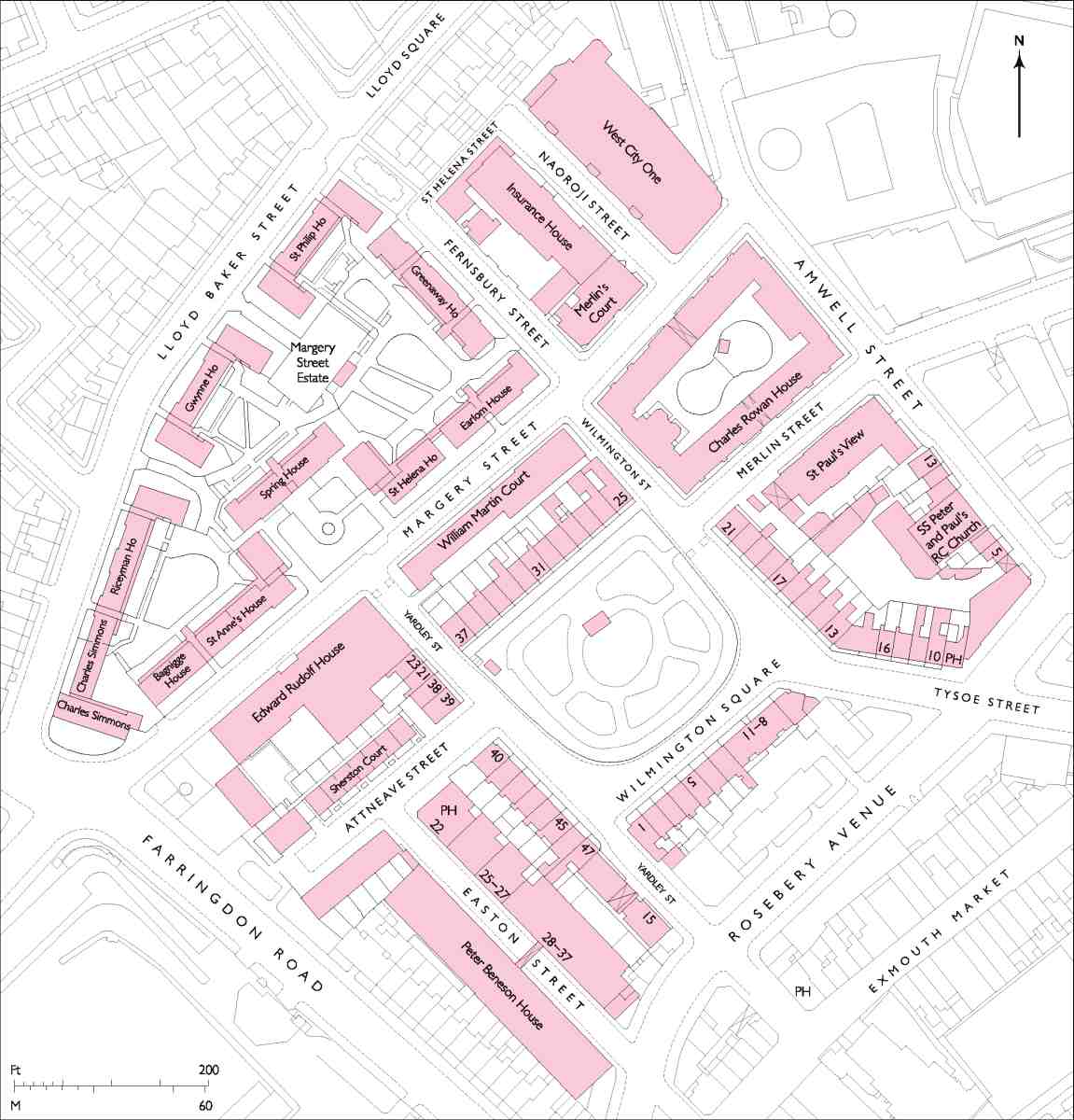

315. Wilmington Square area

Merlin's Cave

Around 1700 an isolated group of humble cottages went up on the knoll between one of the paths and the eastern boundary of Spa Fields, on land now occupied by Merlin Street and Charles Rowan House. One of these cottages, designated 'the Hutt', functioned as a tavern, also known as Merlin's Cave by 1720. The wider area had scattered small resorts, but Merlin's Cave, let to Joseph Cooke, rag merchant and carpenter, was seemingly no more than a tiny pub with views across the fields back to London. It appears to have been rebuilt in 1737 by Joseph Hooke, an erstwhile doctor who in 1735 had established the New Wells theatre nearby to the south (see Chapter III). Hooke's tavern was neither hut- nor cave-like (Ill. 314). It was, rather, a three-bay brick building of two storeys, with cellars and garrets, and contained a 'long room' with a marble chimneypiece. The skittle ground in the gardens was to become celebrated. (fn. 1) (fn. b)

Between the late 1760s and 1790s the other cottages were replaced by a row of about ten houses alongside the tavern, known as Merlin's Place and facing west towards the footpath. The gardens towards what is now Amwell Street were later built over, but these eighteenth-century buildings of brick and timber largely endured throughout the nineteenth century. (fn. 3) The tavern itself was succeeded c. 1833 by the New Merlin's Cave public house at No. 131 Rosoman Street, slightly to the north at the apex of the triangular plot (see Ill. 316). (fn. 4) It moved again in 1921–2 (see New Merlin's Cave, below).

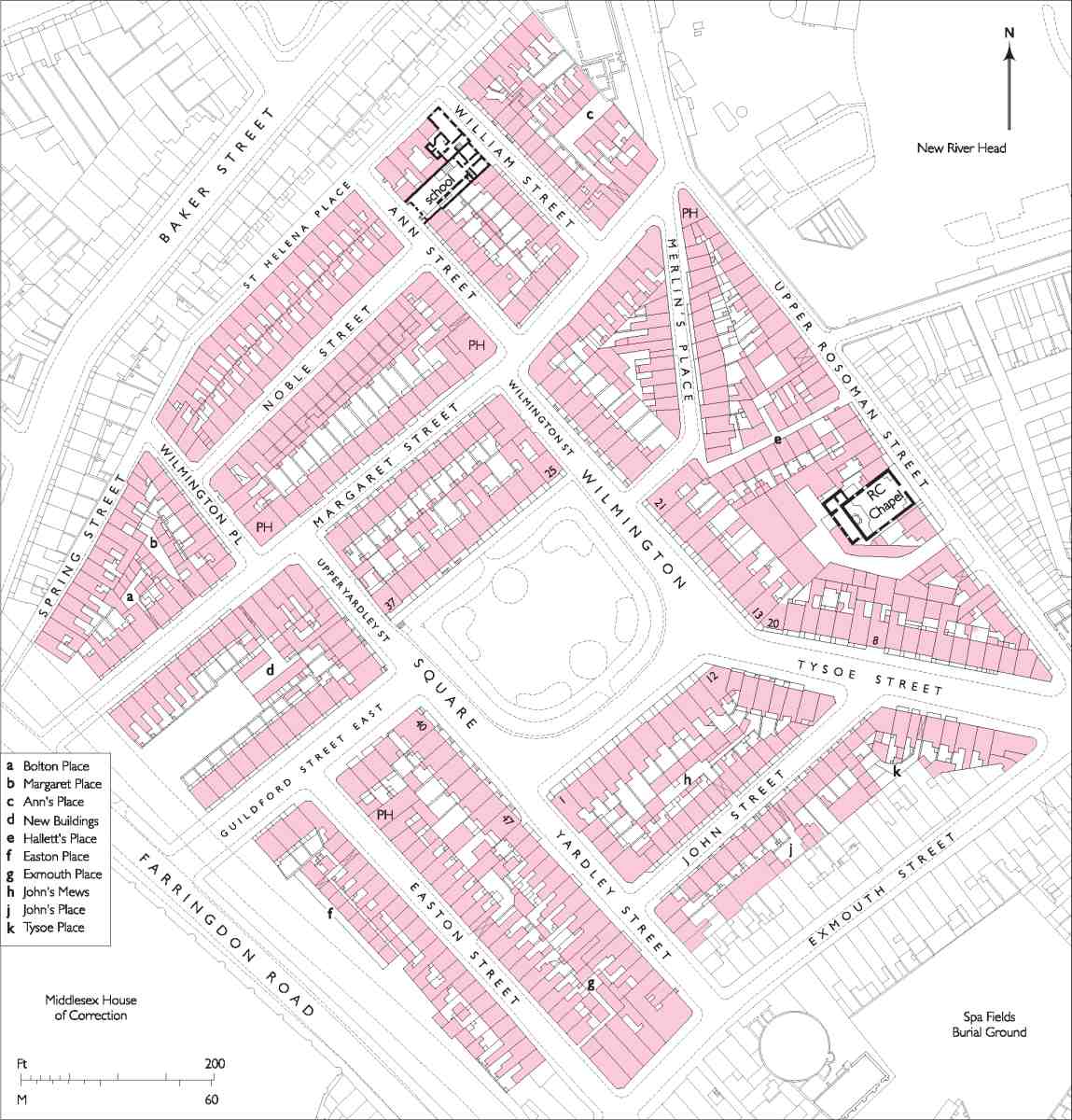

316. Wilmington Square area, c. 1874

317. The third Spa Fields meeting of 10 February 1817, showing Henry Hunt addressing the crowd from Merlin's Cave

The Spa Fields Meetings

The three Spa Fields meetings of 15 November 1816, 2 December 1816 and 10 February 1817—often misleadingly described as riots, following tendentious press reports of the time—were mass assemblies of great moment in the history of English popular radicalism. On each occasion Merlin's Cave, on the field's high ground, was used as the platform from which Henry 'Orator' Hunt addressed the crowd, leaning out of a first-floor window (Ill. 317).

The ultra-radical Society of Spencean Philanthropists organised the first meeting of 'Distressed Manufacturers, Mariners, Artisans, and others', aiming to push for the common ownership of land and hoping to incite insurrection. Following an invitation from the secretary, Thomas Preston, Hunt agreed to address the meeting, but only if it stayed 'constitutional' and focused on parliamentary reform and the widening of the franchise. His purpose at the first meeting of about 20–40,000 people was to rally support for a petition to the Prince Regent, calling for the relief of suffering and the re-convening of Parliament. A second meeting was planned to consider the response. The petition gained 24,479 signatures, yet Sir Francis Burdett declined to present it; the Prince offered a donation of £4,000 to the Spitalfields Soup Committee. On 2 December, before Hunt arrived to address an unprecedented crowd of 50–100,000, a group of insurrectionists, led by Preston, Arthur Thistlewood and James Watson from the original organising committee, waylaid a section of the crowd near the Spa Fields Cake (or Pie) House (Ill. 314). A few hundred headed off to the City where, from Smithfield round to Aldgate, there was violence and looting. In the meantime, and again in February, following a further mass petition, Hunt spoke to orderly crowds on Spa Fields. (fn. 5)

By May 1817 there were buildings opposite Merlin's

Cave, so that 'the tribune window, so recently attractive to

the populace, is now completely enveloped'. (fn. 6) Indeed,

when another meeting was planned for Spa Fields in May

1818 there were notices forbidding trespass, and it was

found that

almost every vacant spot on which a building has not already

been commenced, is either covered with heaps of brick earth,

excavated for laying foundations, or occupied by immense

heaps of bricks, manufactured or preparing for the kiln.

Upwards of one hundred brick makers are engaged upon the

spot. (fn. 7)

Development of Spa Fields, 1816–1830

The Northampton Estate's plans for building on Spa Fields were already in train at the time of the meetings. They followed on from the Estate's development of Woods Close in eastern Clerkenwell, where planning through the 1790s had led in the following decade to the erection of houses on new streets around the central Northampton Square (see Survey of London, volume xlvi). By 1812 this project was almost complete. It had been seen through by Samuel Pepys Cockerell, the Estate's surveyor, working closely with Edward Boodle, agent or steward under Charles Compton, 9th Earl and 1st Marquess of Northampton.

The New River Company had been a tenant of Spa Fields, with seventeen pipes running across it in 1798. These were thereafter re-routed to run to the north and south of the field, opening the way for development. (fn. 8) In 1809–10 there had been discussion about moving the livestock market at Smithfield to the west part of Spa Fields, but this came to nothing. (fn. 9) The New River Company had begun to build on its own fields, laying out Myddelton Street in 1811, but at the end of the war years all of north Clerkenwell west of St John Street and south of Pentonville remained open. While the development of Spa Fields was an obvious next step for the Northampton Estate, it was held up until the post-war upturn in the building cycle. The project was then prosecuted with more alacrity than contemporary development plans in many other places.

On 7 September 1816 Boodle visited Cockerell's office on the corner of Savile Row and Burlington Street and there received an explanation of the surveyor's plan for the development of Spa Fields. The pair agreed a strategy and gained the Marquess's approval to proceed. (fn. 10) Unlike Woods Close the project was successfully assigned to a single contractor, the value of such co-ordination having been made evident to Cockerell through his work with James Burton on the Foundling Hospital estate. (fn. 11) Their man was John Wilson (born c. 1780), a Gray's Inn Lane plumber and glazier who had become a builder and, possibly following on from a father of the same name, been active as a developer around 1808 on Doughty Street, adjoining the Foundling Hospital estate. He had at that time styled himself 'architect'. From 1815 Wilson was acting as a contractor for work at Burlington House in a partnership of 'surveyors' with the young architect George Woolcot, whose timber-merchant father had been one of the main developers at Woods Close. (fn. 12)

Negotiations with Wilson began late in 1816 and he was in possession of Spa Fields and digging by February 1817. Three months later Boodle and Cockerell concluded the deal with Wilson, and the scheme for about 400 new houses was made public. The agreements that Wilson was to enter into were drawn up by Boodle, the land was parcelled off, and by October sewers were being laid and the north side of Exmouth Street had been started (see Chapter III). Building in Wilmington Square was under way in early 1818. (fn. 13)

Cockerell followed the same principles he had adopted for Woods Close, and before that in Bloomsbury, providing a framework for development with various classes of houses. These were to be respectable throughout, but duly separated and diverse enough to attract investors. The focus was to be a large rectangular square at the centre of the field, with its longer sides to the east and west. This was to have roads running diagonally (along the old paths) from the southern corners, and another running from the middle of the west side to Coppice Row. This would have been an important opening to and from the south and west; there was as yet no Farringdon Road or Rosebery Avenue. (fn. 14) Merlin's Place already lay, a bit awkwardly, to the east, but it was incorporated into the layout; other surrounding development was anyway to be allowed to fade to humbler housing at the margins. Save for the southwestern diagonal, abandoned in 1817, this layout was followed, though in due course the square had to be reduced in size. The west approach, called Guilford (or Guildford) Street East and now Attneave Street, was intended to be a 60ft-wide continuation of Guilford Street on the Foundling Hospital estate. This anticipated a straight link over the Fleet across land belonging to the Middlesex Justices, immediately north of the County House of Correction at Coldbath Fields. Despite seeming three-way agreement about this in 1816 between the Northampton and Calthorpe Estates and the Justices, and petitions from Wilson and some of the first householders on his development in 1820, the link-road scheme ran into the sands after protracted discussions in 1821–3. In 1824–5 the prison was enlarged, and the Guilford Street extension was pushed northwards as Calthorpe Street. (fn. 15)

By 1819 the north side of Exmouth Street was largely complete, with rows of houses running back on Yardley Street and Easton Street, as well as along John Street. The first group of six houses on Wilmington Square was up (on the east side), as was No. 8 Tysoe Street. Building on Margaret Street had begun at either end, and a row of cottages opposite the earlier row completed Merlin's Place. (fn. 16) By 1824 the rest of the grid had been filled in, save for the west sides of Wilmington Square and Upper Rosoman Street, where a dairy yard was not enclosed until the late 1830s. (fn. 17)

The principal streets were named after Northampton connections. The Earls of Northampton had an estate at Wilmington, Sussex, and also carried the title Baron Wilmington. Tysoe is a village near the family's house at Compton Wynyates in Warwickshire, and Yardley Hastings and Easton Maudit are villages near their seat at Castle Ashby in Northamptonshire. Margaret probably refers to Margaret MacLean Clephane, who in 1816 married Spencer, Lord Compton, who was to become 2nd Marquess of Northampton in 1828. Their second son, William, 4th Marquess, was born in 1818. (fn. 18) The names John and Ann may relate to Wilson and his family.

Wilmington Square was originally to have extended north to Margaret Street, making it about as big as Myddelton Square. In 1825 Wilson sought to reduce its size, and the rate of buildings intended there, because, he avowed, 'the neighbourhood was not adapted to the occupation of houses of so good a description as those he had begun to build in it'. (fn. 19) He had failed to get his western link road, and the market, which was slumping sharply anyway, would have been suffering from over-supply as a result of the initiatives of neighbouring estates. In 1823 the New River Company had settled building agreements for the development of Myddelton Square, and by 1825 work was under way on substantial houses on the more elevated ground there, as well as on adjoining parts of the New River estate and parts of the Lloyd Baker estate to the north. At first the Northampton Estate (supported by at least one early tenant of the square) would not accede to Wilson's request. (fn. 20)

Acceptance of a reduction in the size of Wilmington Square may have come as early as December 1826, when C. R. Cockerell, with his assistant James Noble, was taking over his father's responsibilities as estate surveyor, and writing to Boodle with advice on the 'disposition' of the buildings in the square. S. P. Cockerell died in 1827, and Charles Compton and Edward Boodle both died in 1828. Only then, it appears, was reconfiguration of the square finally agreed by the estate's wholly new management. (fn. 21)

The elder Cockerell had controlled architectural design in so far as he had provided the overall layout plan and typical elevations. In principle, and through Wilson, he also certified that houses were built according to agreement. Printed building agreements specified 'conformity on the Front Elevation', and were drafted to allow variable specifications as to the construction and materials for third- or fourth-rate houses. (fn. 22) The set-piece square and the wide adjuncts of Tysoe Street and Guilford Street East had some ambition in scale, but there were no great pretensions—even in Wilmington Square second-rate houses were not specified. The bigger houses were outwardly quite flat and plain, only the pedimented palace front on the south side of the square evincing any architectural ambition. There was none of the taut vivacity that Cockerell had given Northampton Square. The fourthrate fringes were more modest, but scarcely different in their architectural vocabulary.

Cockerell also devised the lease covenants, as he had done on Woods Close, but through Wilson there was greater consistency in the leasing, with longer terms. The printed building agreements, as drafted by Boodle and devolved by Wilson, offered 99-year terms running from 1816. They were subject in principle to buildings being completed to Wilson's satisfaction. It was expressly stated that no other buildings, outhouses excepted, should be built behind those fronting the streets. However, as at Woods Close, leases were in fact frequently given in advance of completion, or even commencement, of building. Again, as at Woods Close, this slackness was a primary cause of later problems as it gave builders the opportunity to fit in small houses in courts. There was greater vigilance against this on the neighbouring New River Estate. Following Wilson's head lease there were standard prohibitions against noxious trades, not just in the square, but beyond, and trades or businesses of any kind were prohibited from the front parts of the houses on the square. This was policed more carefully at first, and it was only with the express consent of Lord Northampton in 1824 that one of Wilson's assignees away from the square was permitted to trade as a farrier. (fn. 23)

Wilson sub-assigned to numerous builders. He supplied bricks and probably saw houses through to completion when others ran into difficulties. The main builders on the square, sometimes operating through developer nominees, were James Taylor, Charles Wilmot, Houstoun Rigg Brown and Zachariah Skyring. The latter had worked with Cockerell in Soho in 1801–3 and on St John Street (Islington Road) in 1811. (fn. 24) On the surrounding streets Thomas Wilson, probably John Wilson's brother, built at least thirty-eight houses. William Wilson and Uriah Wilson, a plumber-glazier of Brunswick Square, very likely relatives too, were also involved. (fn. 25) Another of John Wilson's sub-lessees was John Davis, a plasterer, who in 1822 lived on Easton Street and then, later in the year, on Ann Street, when he was building on the corner with Noble Street. Wilson agreed work-for-work or cross-contracting arrangements with Davis, a late instance of a once common practice. But there were problems getting Davis to finish plastering on Tysoe Street in 1823. (fn. 26)

By 1830 infill or back building filled the smallest of gaps 'with streets of a most mean and narrow character'. (fn. 27) Courts of small houses, sometimes in twos and threes (Easton, Exmouth, John's, Tysoe, Hallett's, Ann's, Bolton and Margaret Places), left the area very densely packed, excepting the oasis of Wilmington Square (Ill. 316). Between Noble Street and St Helena Place wash-house wings abutted back-to-back between tiny yards. Such lowgrade density worried the adjacent Lloyd Baker Estate, which would not allow any linking roads between the two estates, for fear of contamination. Demand had disappointed the expectations of the speculators, so supply was modified via infilling. Court development was widespread in early nineteenth-century London, but it was avoidable: the Northampton Estate failed to impose its own covenants to preserve a higher standard. In the 1880s Henry Trelawny Boodle claimed, disingenuously, that these courts had 'been crammed by speculative builders into spots never contemplated by the freeholders for human dwellings'. (fn. 28)

In the early 1890s Rosebery Avenue obliterated some of the area's lesser housing, displacing the south side of John Street and cutting across Easton Street, Yardley Street and Tysoe Street. Guilford Street East became Attneave Street in 1895, probably after Alfred Attneave, a Clerkenwell vestryman. (fn. 29)

Redevelopment since 1920

The early nineteenth-century leases had been co-ordinated to fall in together in 1915. Before his death in 1913 the 5th Marquess of Northampton planned to redevelop Margaret Street with maisonette flats, but this was found to be too expensive after the war, when the estate began to look at the possibility of block dwellings. In the meantime Finsbury Council and the 6th Marquess, with P. F. Storey as his agent and surveyor, advanced a street improvement scheme in 1915. This proposed the removal of Merlin's Place and Hallett's Place and the formation of Merlin Street, along with a recasting of the roads immediately north of Margaret Street, which was to be extended eastwards through the New River Head site where the Metropolitan Water Board was then building its new headquarters. The Estate offered some sites to the council in 1919–20, but neither could yet afford to build. A third party, in the shape of the Post Office, stepped in, and by 1921 had cleared large areas around and north of Margaret Street, eradicating many courts, for an office-building scheme that ultimately came to nought. (fn. 30)

Redevelopment did follow slowly through the 1920s and into the 1930s. The first new buildings in the early 20s were private ventures: two garages and the New Merlin's Cave public house, all on Margaret Street. By the late 1920s the estate had been discouraged from building housing, the view from the Ministry of Health being that 'Finsbury was really wanted for commercial purposes'. (fn. 31) Decisive action towards recasting part of the area for industry was taken on Easton Street, which was all but entirely redeveloped with factories in the late 1920s and 30s. The formation of Merlin Street remained pending until 1928, after which the municipal authorities took control of the Margaret Street area, shifting the focus from commercial to public provision. On the north side of Merlin Street the Metropolitan Police built Charles Rowan House, a large block of married-quarters for policemen, in 1928–30, and on the south side Finsbury Council erected public baths in 1931–3. Meanwhile the council carried through its first major housing scheme, at Margaret Street in 1930–3, nine generously specified blocks of flats and maisonettes, accounting for most of the Northampton estate between that street and Lloyd Baker Street.

On Wilmington Square and Tysoe Street the Northampton Estate undertook the conversion of some houses into flats, from 1920 into the 1930s. After the Second World War, in a climate that prioritised compulsory purchase by local authorities for new housing, it was Finsbury Council that undertook the rebuilding of a bomb-damaged section of the square as flats. In 1951 the Board of Trade would allow no more industries in Finsbury save in exceptional circumstances. The estate itself was sold off in pieces in the 1940s and 1950s. (fn. 32)

In the late 1960s and 1970s most of the south side of Margery Street round to Attneave Street was redeveloped by Islington Council, which also undertook some early conservation-minded rebuilding on Yardley Street during this period. In the 1980s some redundant industrial buildings became offices, notably for Amnesty International on Easton Street. Finally, some plots on or near Amwell Street have gained their third generation of buildings, with private developments that include St Paul's View of 1995–7 and WestCityOne of 2001–5, the latter incorporating a nursery school and a health centre, as well as private flats.

South of Margery Street

South of Margery Street the street pattern remains largely unchanged since its original development, with the exception of Merlin Street. Wilmington Square also maintains its early nineteenth-century appearance, but this constancy of streetscape extends little further than to one side of Tysoe Street and beyond to a short stretch at the bottom of Amwell Street. Detailed discussion of the buildings starts with the square and proceeds to these other sections of early fabric, before looking at the area's social and business character, and then considering the piece-by-piece redevelopment of other southerly parts.

Wilmington Square, Tysoe Street and Yardley Street

Following Cockerell and Boodle's first plans of 1816 the layout and name of Wilmington Square were settled during 1817. By the end of that year the first building agreements under John Wilson were ready to be signed. Arrangements for making the square itself were agreed in 1819, when work began on the railings. (fn. 33)

As to the square's houses, the sequence of development was essentially clockwise, from east to north. Most of the east side (Nos 15–21) came first, in 1818–21, with responsibility delegated to several sub-lessees. James Taylor, builder, took on Nos 19–21, and may have been responsible for building the larger group under other nominees (Ill. 320). Wilson was himself living in No. 16 by late 1819. (fn. 34) George Goodwin Esq., of Chapel Street, Grosvenor Place, took on the whole south side (Nos 1–12), and the adjoining seven houses along the south-west side of Tysoe Street in 1821–5, with Charles Wilmot. A builder, who also styled himself 'architect and surveyor', Wilmot was also active in these years on the New River estate, building on Myddelton Street, where he lived, and Garnault Place. (fn. 35) Wilson moved into the big corner house at No. 12 when it was complete in 1825. The eight houses at Nos 40–47 were built in 1826–30, probably through a sub-lease to Houstoun Rigg Brown. (fn. 36) Along with No. 12 Wilson also appears to have retained No. 44 from the early 1830s. His barrister son William lived there, in later years with his elderly father, described in the 1851 Census as a 'proprietor of houses'. (fn. 37)

Disappointed expectations led Wilson in 1825 to request the change of plan that reduced the size of the square, infilling its northern section in a compromise settled in 1828 (see above). As Cromwell put it, the square was 'completed in a form more circumscribed than was at first determined on, and with houses of a less lofty character'. (fn. 38) Placed in what was to have been part of the square garden, the houses of the north side, completed in 1830, ended up behind a high pedestrian walk rather than a road (Ills 318, 321). In 1828 Zachariah Skyring, a builder and surveyor, applied to connect the drains at No. 25, and the first resident of No. 33 was William Henry Skyring, surveyor, probably Zachariah's son. It seems likely that the Skyrings were responsible for building the whole terrace. (fn. 39) The square was not complete until 1840–1 when Wilson built Nos 38 and 39 at the north end of the west side.

318. Nos 25–37 Wilmington Square (north side) in 1945

319. Nos 1–12 Wilmington Square (south side) in 1945

320. Nos 16–21 Wilmington Square (east side) in 2006

321. Nos 25–37 Wilmington Square (north side) in 2006

Wilmington Square

322. Wilmington Square, south side, elevation to square in 2007

Built over basements with areas, the houses rise to three storeys on the north side, and four on the others, providing eight or ten rooms in each. The fronts are 18ft wide and have rusticated stucco on the ground floors. The plans are of standard rear-staircase type; interconnecting rooms were probably general on the lower storeys. Some houses had first-floor 'statuary' chimneypieces and waterclosets. (fn. 40) The south side (Nos 1–12) has a rather ponderously grand 26-bay palace front, with crossed laurel branches in a central pediment (Ills 319, 322). The gablet (remade c. 1989) over No. 12, the easternmost house, may have been an early alteration; the answering pediment at the west end over No. 1 is a post-war addition. The humbler north side of the square has a faint echo of this treatment, with similar emphasis on the centre and ends, through shallow projections and first-floor round heads and relieving arches. There are round heads on all the ground-floor openings, but not the continuous first-floor arcading that was used at Northampton Square. The east and west sides lack equivalent regularity, unavoidably because of the square's shrinkage, which left the side streets awkwardly off centre. Even so, the early buildings at Nos 13–21 have shallow breaks grouping the houses into threes, and giving slight emphasis to the ends and centre. Taylor's earliest group at Nos 19–21 has guilloche panels under the first-floor windows. On the west side, built after the change of plan, only the outer of the eight houses break forward, with first-floor round heads alone on No. 40 to the north, where the top storey is another late twentieth-century addition. Around the square as a whole there are many early four-panel doors, often with central roundels, fluted pilaster doorcases, and umbrella fanlights. There are also first-floor cast-iron balconies and window guards, with stock lattice, fret, anthemion and Gothic patterns.

The square's end-terrace houses have side-porch entrances. No. 12 was John Wilson's own, a bigger house incorporating an additional full-height bay in the canted return to Tysoe Street. This bay contains an open-well staircase that has survived workshop or factory use and sub-division into flats (Ill. 324). No. 1 always included a three-storey rear wing (now No. 1A) to Yardley Street that was long part of a doctor's surgery. No. 21 had its own chaise-house and stable to the rear. The houses on the south side of the square had some stabling in John's Mews. (fn. 41)

Some sense of the smaller scale of the rest of the area's original houses survives at Nos 21 and 23 Yardley Street, a three-storey pair of 1835–6, built by Wilson with 16ft fronts. Stucco architraves and square-headed openings betray its late date. (fn. 42)

Among few significant early alterations to the houses in the square, a mansard attic was added to No. 35 in 1880 (rebuilt c. 1980), by and for William Randall, a painter and builder, who also rebuilt parts of the front walls of Nos 26–28 in 1883, the back walls of Nos 40–45 in 1890, and the front and flank walls of No. 1 in 1894. An attic was added to No. 25 in the early twentieth century. (fn. 43)

During the twentieth century many of the square's houses were converted, and sometimes rebuilt, following on from less formal subdivision. The Northampton Estate carried through an early lateral conversion in 1920 at Nos 18–21, making ten flats of the four houses. Further conversions by the Estate followed, in 1934–6 at Nos 12–14, along with extensive rebuilding at Nos 18 and 20 Tysoe Street, and in 1937 at No. 6. (fn. 44) Nos 18–21 were acquired by Finsbury Council in 1961, and further substantial rebuilding was needed in 1980–1. (fn. 45)

Nos 8–11 suffered serious bomb damage during World War Two (Ill. 319). Following compulsory purchase by Finsbury Council these houses were rebuilt in 1950–1 by Henry Kent Ltd, to designs by George Hebson, the borough engineer. This was an early post-war facsimile restoration that provided eight three-bedroom flats with a single front entrance and balcony access to the rear. (fn. 46)

Nos 38 and 39 were wholly rebuilt in 1968–9 by Islington Council as eight flats behind one street entrance. Alfred Head, borough architect, gained praise for what was considered a conservation project, as he did for similar redevelopment at No. 15 Yardley Street (Ill. 323). Built in 1969–71 by A. T. Rowley (London) Ltd to replace seven houses of 1817–19, this block of fourteen old people's one-bedroom flats was given what was termed a 'Victorian style façade'. In fact it follows its Regency forerunners with stock brick above ground-floor stucco, and railings cast from a recovered mould. Yet it has an irregular bay rhythm, only one entrance and a flat-headed carriageway through to the rear where there are access balconies. Head said 'What we have put back is meant to have a matching effect with the square, not to match it in every detail'. (fn. 47) Since 1970 there has been much further piecemeal conversion and rehabilitation work in Wilmington Square.

323. No. 15 Yardley Street in 2007

The following table summarizes development in and around Wilmington Square in 1815–41 and principal later changes. (fn. 48)

South side

Nos 1–12 (with Nos 9–21 Tysoe Street, demolished). John Wilson, with George Goodwin, sub-lessee, and Charles Wilmot, builder, 1821–5. Nos 8–11 rebuilt 1950–1

East side

Nos 13 and 14 (with Nos 14–20 Tysoe Street). John Wilson, with John Cantellow, plasterer, 1821–5

Nos 15–21. John Wilson, 1818–21, with sub-lessees James Taylor, builder (Nos 19–21); William Cornelius Swift, pewterer (No. 17); John Monkhouse (No. 18)

Nos 22 and 23. John Wilson, with Francis Child, sub-lessee, 1821. Demolished

No. 24 (with Nos 1–6 Wilmington Street, demolished). John Wilson, 1827–9

North side Nos 25–37. John Wilson, with Zachariah and William Henry Skyring, builders, 1828–30; No. 31 sub-let to John Walter Cropley

West side

Nos 38 and 39. John Wilson, 1840–1. Rebuilt 1968–9

Nos 40–47. John Wilson, with Houstoun Rigg Brown, sublessee, 1826–30

324. No. 12 Wilmington Square, reconstruction of original plan

Tysoe Street

No. 8. John Wilson, for William Hallett, cow-keeper, 1818. Later Three Crowns public house

Nos 10 and 12. Francis Child, sub-lessee, 1821–5. No. 10 refronted 1932

Nos 14–20. John Wilson, with John Cantellow, plasterer, 1821–5 (with Nos 13 and 14 Wilmington Square). Nos 18 and 20 part rebuilt 1934–6

Yardley Street

No. 14, with adjoining houses to south and Wilmington Arms public house. Isaac Woodroffe, sub-lessee, 1818–19, rebuilt and enlarged 1927–8. Shopfront of 1932; Wilmington Arms rebuilt and enlarged 1927–8

Nos 11–17. Thomas Gooch, watchcase maker, sub-lessee, 1817–19. Rebuilt 1969–71 as No. 15

Nos 21 and 23. John Wilson, 1835–6

Social and commercial character

The first residents of Wilmington Square, in the late 1820s and 1830s, included Thomas Starling, map engraver, at No. 1; the Rev. William John Hall, compiler of a popular collection of psalms and hymns, at No. 10; and Samuel King, attorney, at No. 46. Golding Bird, a 'brilliant' young physician, (fn. 49) lived with his parents at No. 22 for a few years before moving to Myddelton Square in 1842. By this time surgeons occupied Nos 1 and 1A, where a medical presence was maintained up to the 1940s; the adjoining shop at No. 14 Yardley Street was formed in 1932 for a hairdresser, but it soon after became Finsbury Dental Laboratories. In the 1840s solicitors occupied Nos 16 and 17, and there were Customs and Excise officers at Nos 4 and 23. At No. 33 Skyring was followed around 1850 by Robert James Brede, a young architect and surveyor, and thereafter Thomas Aspray and James Ellis, surgeons, were at Nos 12 and 39. Father John Kyne, the Irish Catholic priest of SS Peter and Paul's Church, Amwell Street, lived at No. 11, and William Lewis & Sons, solicitors, were at No. 7 from c. 1860 up to at least 1938. (fn. 50)

As elsewhere in north Clerkenwell there was an artistic element. George Almar the playwright, who was active at Sadler's Wells, lived at No. 43 Wilmington Square in the early 1830s. (fn. 51) At Wilmington House, on the south side of John Street, T. G. Flower's Dramatic Institution was a small theatre that lasted only until 1834. Here Louisa Cranstoun Nisbett, later Lady Boothby and a famously spirited actress, performed as a girl with her father Frederick Hayes Macnamara, who had short careers as a soldier and a West India merchant before he tried the stage. (fn. 52) Joseph Stirling Coyne, the Irish dramatist and journalist, lived at No. 2 Wilmington Square in the 1850s, during which decade another dramatist, E. L. Blanchard, also gave Wilmington Square as his address. Through the later decades of the nineteenth century the square was home to Henry Fletcher Reason, engraver, at No. 23 in 1860–90; Richard Sparks, engraver, at No. 37 in 1870; Robert Cain, lithographer, at No. 24 in 1880; and Otto Richmer, chromo-lithograph artist, at No. 39 in 1880–1900. The adolescent Aubrey Beardsley worked at No. 3 in 1889, as a clerk in the office of Ernest Carritt, the District Surveyor. (fn. 53)

Merchants and trades became increasingly represented in the social make-up of Wilmington Square. In the 1830s Thomas Paris, brewer and coal merchant, was the first occupant of No. 47, and Richard Simonds, grocer, tea dealer and coal merchant, had No. 7. These were their homes, not shops, but other houses were probably in business use. In the early 1830s Thomas Massey, watchmaker, was the first resident of No. 32, and Samuel Cuendet, a Swiss gold-watchcase maker, had No. 9 from the 1830s to the 1850s. In the early 1840s there were more watchmakers—Richard Frederick Wilmot above the doctor's premises at No. 1/1A, and Thomas Corbett at No. 46, with his wife, seven children, four apprentices and single servant. A decade later, there were yet more watchmakers, as well as some jewellers, and Jules Wauthier, a French barometer maker, at No. 45. In 1853 Robert Barnby, mathematical-instrument maker, built a workshop at the back of the garden of No. 35. Barnett Weigel, who was Austrian, or George Evans, both jewellers, built a workshop behind No. 27 in the late 1870s or 1880s. In the later decades of the nineteenth century watchmaking, jewellery and related trades were present in around a third of the houses in the square, concentrated in the smaller houses on the north side, with a number of French immigrants and, by contrast, Horatio W. Nelson, a gold-chain maker, who had been born in Southwark c. 1820, at No. 17. (fn. 54)

By the 1850s the square had also become a centre for the making of artificial flowers, again by French and German immigrants. No. 46 was now divided into two households, headed by two Frenchmen, Isaac Samuel, an 'artificial florist', and Lambert Samuel, a commercial traveller, whose German wife, Leopoldine, was another flower maker. Next door, No. 47 was also divided, with one household headed by Jules Lamy, a Parisian of the same trade, who accommodated five unmarried female flower makers in their 20s, and two younger female English apprentices. More of this craft was represented at No. 30, where John Ebertsheuser, a Prussian, lived with five female apprentices and, in 1852, built an office building at the back of the garden; and at No. 32, which was divided into four households—headed by four Frenchmen, two married, one a flower maker, the other three lithographers. Trimming manufacture, related to flower making, was carried on at Nos 13 and 18 in 1860. Ebertsheuser moved to part of the bigger house at No. 21 by 1870, and artificial-flower making continued in the square well into the twentieth century. Italian immigrants, Antonio and Pietro Benzoni, flower makers, were at No. 14 from before 1860 for at least half a century, and at No. 46 Mrs Elizabeth Usher ran an artificial-flower business from c. 1880 to the 1920s, using a workhouse built in 1872 for a printer's joiner. (fn. 55)

There was much residential and commercial sub-division of the houses. In a sign of things to come, No. 39 was a boarding house by 1860. Ten years later No. 3 was a young ladies' school, No. 7 had been partially adapted as offices for the Association for the Protection of Workers and Dealers in Precious Metals, which insured tradesmen against loss through theft, and the Standard Loan Office was at No. 38. (fn. 56) After another decade No. 21 had become a mission-house for the future Holy Redeemer Church, with the Rev. Edward V. Eyre resident; the mission later moved to No. 16. In the 1880s more than half of the square's houses were in divided occupation, and many of the others had boarders. No. 40 had four households and twenty-four people resident, and house farmers were said to be active in the square as well as in the side streets. There was a continuing professional presence, including clergymen, doctors and architects (Ernest Carritt and Bertram Parkin Haigh). Despite office use the square had become considerably more crowded, those recorded as resident in censuses rising from 318 in 1851 to 501 in 1901, when No. 37 had five households and No. 42 six. (fn. 57)

Around 1900 the watch and jewellery trades began to move away, though there were some new arrivals, includ ing Mrs Emilie Hamburger, a French diamond merchant, in No. 6 and Leendert De Koningh, a Dutch jeweller, in No. 11. Other craftsmen arrived, Luigi Carini, mosaic worker, at No. 9, and Thomas William Nott, wood-carver, at No. 42. Such metal trades as did remain were concentrated on the north side of the square, using rear workshops into the 1930s; silversmithing continuing at No. 37 throughout the 1950s. (fn. 58)

After the First World War No. 9 became the Finsbury Discharged & Demobilised Sailors' and Soldiers' Working Men's Club & Institute, and was later used by the British Legion and the Finsbury United Services Club Ltd, which moved to No. 16 in the 1940s, displacing the Holy Redeemer mission. The east side had been otherwise largely municipalized, with council flats at Nos 18–21, and other premises let to the Metropolitan Water Board and the Metropolitan District Nursing Association. Most of the houses on the north and south sides were divided into flats, some through formal conversions, with Nos 36 and then 35 becoming homes to the Pallottine Missionary Sisters, a Roman Catholic foundation. (fn. 59)

Nos 45 and 46 were guest-houses by the 1950s, becoming the Wilmington House Hotel, which was in use into the 1990s for bed-and-breakfast accommodation. As Lintons House, No. 7 is another hotel. Gentrification was another factor in the late twentieth-century decline of the square's residential population, through the re-conversion of flats to houses, especially on the north side. Between 1966 and 1985 the number of registered electors halved. In recent years the square has attracted fashionable and well-known figures, notably the politician Peter Mandelson and the ceramic artist Grayson Perry. (fn. 60)

Wilmington Square garden

Wilmington Square's garden was at first reserved for the private benefit of the square's lessees. It is laid out as a D, its flat side to the north (where the square was truncated in 1828), its southern corners rounded, seemingly a reconfiguration of an early two-part arrangement as an ellipse below a rectangle. (fn. 61) The cast-iron railings that were going up by 1819 appear to survive, with a blocked gate at the centre of the south side. They have reeded square-section standards and pine-cone or pineapple finials, some presumably moved in the late 1820s.

The possibility of building the church which was to become Holy Redeemer, Exmouth Market, in the square was considered in 1883 but, in the wake of the investigations of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes, the garden was given to the public, along with that in Northampton Square, at the suggestion of a Captain Thompson. It opened in 1885 with a new layout, designed by the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association's landscape gardener, Miss F. Wilkinson. The improvements, which included a fountain, a drinking fountain and iron flower urns, were paid for by Charles Clement Walker, a Clerkenwell-born Shropshire JP. Management was transferred from the MPGA to the Vestry in 1887. (fn. 62)

325. Wilmington Square garden, shortly after construction of shelter in 1931

Children were not at first admitted unless accompanied

by an adult. Popular today, the garden cannot have been

busier than when the architect G. L. Morris described it

in the 1920s:

On Saturdays the broad asphalt paths teem with children from

the dwellings of the surrounding neighbourhood, boys and

girls of all sorts, sizes, and conditions, barefooted and booted,

and sometimes spurred, careering up and down in their primitive carriages drawn by spotted horses on wheels. Scooters of

strange form and many another weird contraption pass swiftly

to and fro to the delight of the genial and elderly men sitting

on the seats basking in the sunshine and living their youth

over again in the scene before them. With some degree of

truth this garden might be described as the Rotten Row of

Clerkenwell. (fn. 63)

In 1931 the fountain was replaced by a public shelter, erected by Finsbury Council to designs by the borough engineer, A. V. Cole (Ill. 325). Glazed screens on the north side have been removed. An office-cum-store building was built in the north-west corner in 1933, and the original drinking fountain, which survives, was supplemented by another, erected by the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association. There were some large trees in the square until after the Second World War, but these have gone, save for one plane towards the north side. (fn. 64)

Buildings in Amwell Street

This section discusses buildings on the west side of Amwell Street between Rosebery Avenue and Merlin Street. The east side of this part of the street is described in Chapter IV, and the northern parts, including the west side of Claremont Square, in Chapter VIII; St Paul's View is dealt with below under Merlin Street. The southern stretch of Amwell Street was called Upper Rosoman Street from its first development until 1877, when it was renumbered as part of Rosoman Street. In 1936 it was made part of Amwell Street and again renumbered.

326. Amwell Street, west side in 2006, Left to right: Nos 3–13; SS Peter and Paul's Roman Catholic Church, centre (John Blyth, architect, 1835–8)

Facing New River Head and a field to its south, Upper Rosoman Street's west frontage was one of the last parts of Spa Fields to be developed. The New River Company formed the street and developed the east side with a long row of modest houses in 1819–22, but the west side continued to face yards: to the north that behind Merlin's Cave (see above), to the south that of William Hallett, a cow-keeper who lived at No. 8 Tysoe Street from when it was built in 1818 until the 1840s. The link between this house and the land behind appears to have been severed in 1848 when a shop front was installed. Initially occupied by a milliner, the shop soon became a beer-house. Its front was remade in 1883, by which time the building had become the Three Crowns public house. (fn. 65)

John Wilson took a lease of the whole Hallett's Yard site in 1826, undertaking to build ten fourth-rate houses along Upper Rosoman Street, in a row to the north of the dairy–yard entrance, with three more facing Hallett's Place, a narrow alley on the yard's north side. Only one of the latter had been built by 1830, so Wilson was granted five more years to complete the development. But by 1835 he had overseen no more than the addition of a chapel, now a Roman Catholic church, on three of the Upper Rosoman Street plots. The house to the north (No. 9) was up and occupied by 1837, and two to the south and four more to the north followed by 1838. Hallett's Place was given eight small houses, where three larger ones had been intended. On Amwell Street all but the northernmost pair of the seven late-1830s houses survive, looking old-fashioned for their date (Ill. 326). Buildings to the rear in Hallett's dairyyard were replaced in 1849–52 by Thomas Jelley of Bloomsbury, who still had cowhouses there in 1880. The southernmost house (No. 3) extends across the yard entrance and so has a non-standard plan. It has latterly been joined with No. 5 to serve as presbytery to the adjoining church. No. 5 has lower-level stucco and a passage alongside the church that gave access to a school at the rear. No. 13 always incorporated a shop, and had a foundry to the rear by 1874. This was long occupied by Frederick Bowman, brass-founder, and his successors. The shopfront is perhaps partly datable to 1912. (fn. 66)

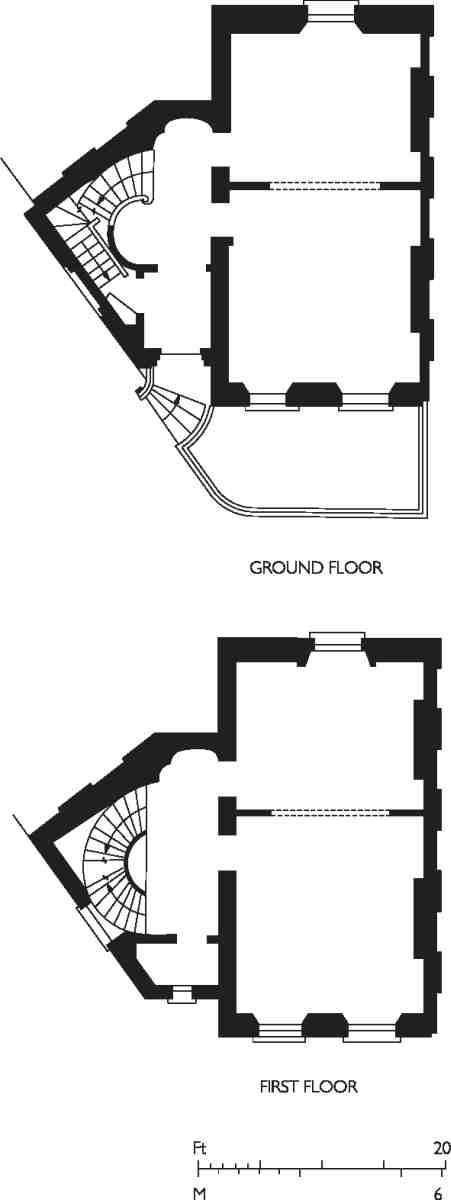

SS Peter and Paul's Roman Catholic Church and School

This was built in 1835 as Northampton Tabernacle, for members of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion who had broken away from Spa Fields Chapel (see Chapter III). The architect was the local surveyor John Blyth. This congregation did not last long, and in 1847 the building was bought at auction by a Roman Catholic mission that had been founded by Father John Mearn in 1842 and set up in Saffron Hill with two Spanish priests. Bishop Thomas Griffiths, Vicar Apostolic of the London District, provided half the money, and the first priests at Rosoman Street were Irish. This was an early instance, possibly the first, of the conversion of an English Protestant church for Roman Catholic usage. (fn. 67)

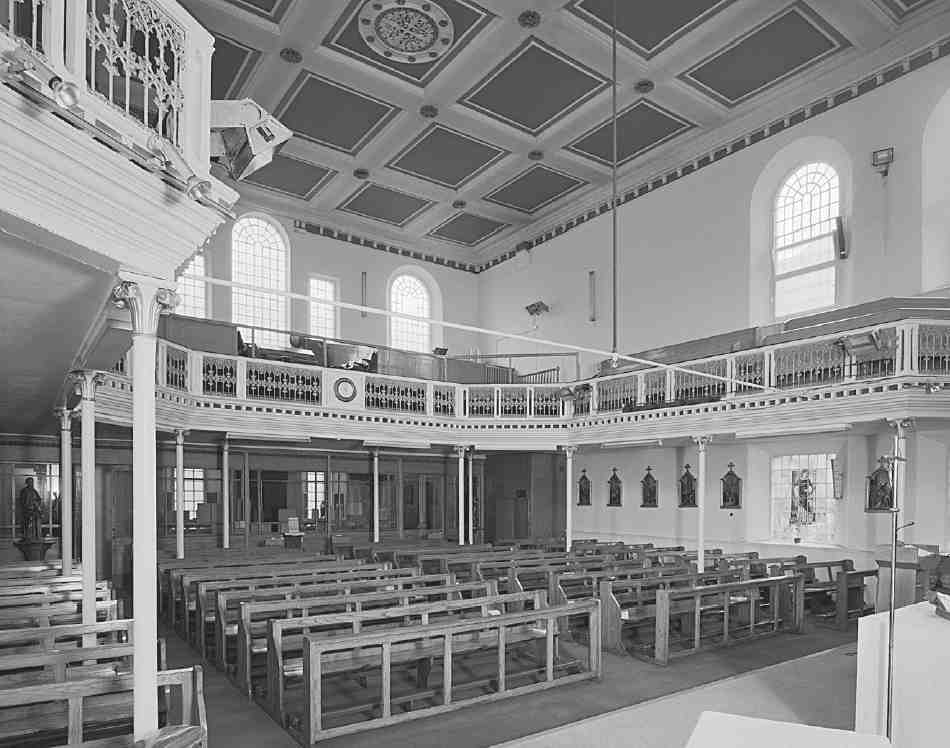

327. SS Peter and Paul's Roman Catholic Church, interior looking towards entrance in 1990

The church is a simple rectangular box under a hipped roof. It has a symmetrical Classical façade with stucco dressings and entrances in each of its three bays (Ill. 326). The slightly projecting central bay carries an engaged tetrastyle Ionic frontispiece below a balustraded Venetian window. The outer entrances lead to staircases that rise to an original three-sided gallery standing on cast-iron columns with loosely Corinthian capitals (Ill. 327). This was re-fronted with Gothic-traceried openwork cast-iron panels as part of a Gothic improvement scheme of 1856 that included an altar and altar rails. The flat ceiling is coffered with three ornamental cast-iron vents. The sanctuary wall, to the west, reflecting the building's Protestant origins, has full-height blind arcading on Corinthian pilasters. (fn. 68)

Since 1952 the church has been a centre of the Pallottine Fathers. Ambitious plans for redevelopment of the whole site in 1959–62 came to nothing. Instead the church has been reordered, with a glazed partition of 1972 to the vestibule, and a set of carved-relief oak liturgical furnishings of 1984–5 made by Ormsby of Scarisbrick Ltd to designs by J. J. Ormsby, showing the supper at Emmaeus on the altar. The oil-on-canvas Stations of the Cross have been attributed to Mayer as Victorian studio work. There is a crucifix of the type made by Ars Sacra, and cast statues of SS Peter and Paul are signed 'Hall, Paris'. Four stainedglass windows depict SS Anthony of Padua, Vincent Pallotti ('CE fecit'), Thérèse of Lisieux (in memory of John Wilson and members of the Wilson and Caffrey families) and Martin de Porres. A nineteenth-century 'west end' window depicting SS Peter and Paul has been lost, perhaps when the adjoining school was enlarged. (fn. 69)

Soon after 1847 a school was established behind the church, alongside the dairy buildings of Hallett's Yard. It appears to have begun as one long classroom, rebuilt as a larger two-storey block in 1877, with M. G. Leggett as builder. This placed infants below older boys and girls in four classrooms, but the school remained crammed in alongside the cows. Criticised as cramped and inconvenient, the Rosoman Street Catholic Schools, as they became known, were the subject of plans for further alterations and additions from 1887, when there were 323 children attending. But it was only in 1907–8, with the threat of closure and the imposition of a maximum roll of 215 children, that another two-storey classroom block was added to the south, to designs by Robert L. Curtis, with Alfred E. Symes as builder. The former dairy yard was cleared in 1915 to provide a playground, enlarged in 1923–5. Around 1930 an open-air class was introduced, and in 1955–6 an assembly hall was built on the north side of the playground. The school moved to Compton Street in 1978 (see Survey of London, volume xlvi), since when the yard has been used for private car parking. Upperstorey rooms in the former school are let to the Latin American Bureau as charity offices, and the ground-floor classrooms are still used for church teaching. Victorian glazed partitions survive. (fn. 70)

Merlin Street

Charles Rowan House

To the north of the newly formed Merlin Street, and across the site of Merlin's Place, Charles Rowan House was built in 1928–30 as flats for married policemen and their families. It was generally acknowledged that housing policemen in large barracks away from the rest of the population was undesirable, but in 1903 the Metropolitan Police began to provide purpose-built married-quarters in central districts where decent affordable housing was scarce, making it difficult to call on men at short notice.

328. Charles Rowan House. Wilmington Street front from the south-west in 2006

But by 1916 accommodation for only 122 men had been provided, and in 1920 it was recommended that 800 new flats should be built. Progress with this programme continued to be slow, but in the late 1920s two big projects were realized, with ninety-six flats each: Edward Henry Buildings in Cornwall Road, Lambeth, completed 1928, and Charles Rowan House. These were the largest concentrations of policemen in London. (fn. 71)

Gilbert Mackenzie Trench, architect and surveyor to the Metropolitan Police, designed both blocks, the Finsbury building in 1927. Its builders were T. H. Adamson & Sons, and it was named after Sir Charles Rowan, the army officer appointed by Robert Peel in 1829 as one of two commissioners to organize London's new police force. Of five storeys, with plain stock-brick internal elevations under flat roofs, the block provided sixtyeight three-bedroom and twenty-eight two-bedroom flats. Each had its own scullery, integral bathroom and WC, designated uniform cupboard and small internal balcony. There were also twenty-four pram shelters and a basement playground (Ills 328–30).

A massive and austere presence on a sloping enclosed

site, the distinctiveness of Charles Rowan House lies in its

style. The power of compressed rhythmic verticality, with

patterned brickwork and chimneystacks that rise as battlements, shows awareness of recent German and Dutch

architecture. Mackenzie Trench (with Charles A. Battie)

had used the same idiom in the six-storey Edward Henry

Buildings, of which it was said:

That the police should inspire in us the proper awe is eminently desirable, and there is something to be said for giving

to a police-station a rather forbidding appearance. It is,

however, carrying architectural symbolism a little too far that

even the wives and families of policemen should be housed in

a building of such astonishing severity. (fn. 72)

329. North and south elevations, 1927

330. Second-floor plan, 1927

Charles Rowan House, Merlin and Margey Streets. G. Mackenzie Trench, architect, 1928–30

Charles Rowan House was transferred to Islington Council in 1974 to become council housing. Deterioration led to proposals to redevelop, and continuing decline left many flats empty. Squatters moved in, the Charles Rowan Housing Cooperative was set up, and there was much discord about tenure. The block was listed in 1994 and its rehabilitation has included a re-landscaping of the courtyard in 2001–2, to designs by landscape architects Farrer Huxley. (fn. 73)

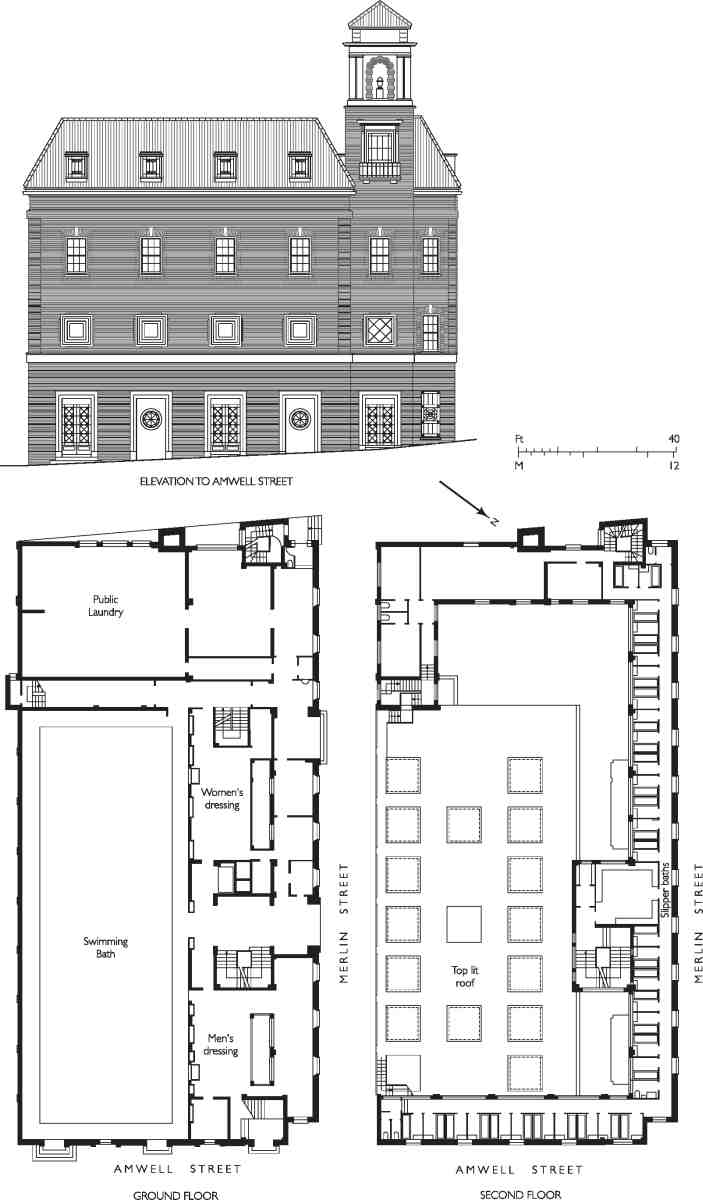

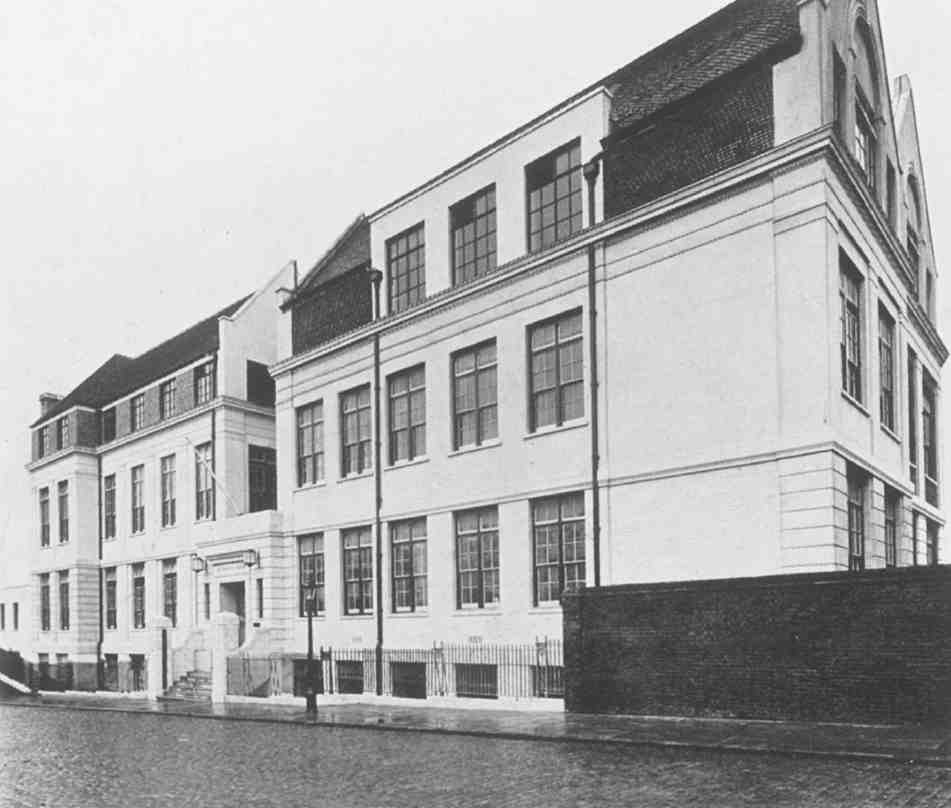

Public baths (demolished)

Development on the south side of Merlin Street followed Charles Rowan House with the erection in 1931–3 of Finsbury Borough Council's public baths and wash–houses. The Vestry had not, despite discussions at various dates, built baths. (fn. 74) Various private facilities and, from 1896, those of the Northampton Institute had to suffice. It was not till the late 1920s that the council acted to provide public baths, at Ironmonger Row in south Finsbury. The architects of these and the Merlin Street building were A. W. S. and K. M. B. Cross, bathhouse specialists, designs for the latter probably being prepared by the son, Kenneth Cross, who had published Swimming Baths in 1928. At Merlin Street the builders were Bovis Ltd. The discovery of water close to the surface and other poor ground called for reinforced-concrete piling and retaining walls for the foundations of the steel-framed structure. (fn. 75)

The dignified handling of its corner site gave the building considerable townscape value, classical equilibrium contrasting markedly with the dynamism of Charles Rowan House (Ills 331, 332). Its façades were of polychromatic brick with Portland-stone dressings and dark-red Italianate tiled roofs. Campaniles that lacked any functional justification were set back at either end, framing the symmetrical 11-bay elevation to Merlin Street. Inside, innovative radiant panels let into the walls and ceilings heated the standardsize pool of 100ft by 35ft, under a skylit segmental-arched vault (Ill. 333). The space was designed with the possibility of conversion to a public hall or entertainment venue during the winter. Ninety slipper baths with terrazzo partitions lined the north and east sides of the building on its upper storeys. The public laundry had both washing troughs and washing machines, and rooms for mangling and ironing. (fn. 76) In 1962 modernizing alterations designed by Herbert Wright & Tidmarsh turned the laundry into a fully automated self-service facility. (fn. 77)

331. Public Baths, Merlin Street, elevation and plans as designed. A. W. S. and K. M. B. Cross, architects, 1931–3. Demolished

332, 333. Public Baths, Merlin Street. View from north-east and swimming pool in 1933

Declining use and the rising value of the site led to closure of the baths in 1988, despite opposition. Plans for a mixed-use redevelopment that prioritised public leisure facilities were superseded by a speculative residential scheme. Islington Council refused permission for the demolition of the unlisted baths, but the planning case went to appeal and in 1994 rebuilding was permitted. The result was St Paul's View of 1995–7, developed by Goldcrest Homes and designed by CHBC Architects, with Peter Steadman as job architect. Building was interrupted by a sensational fire in May 1996. This block comprises thirty-one flats in four storeys, with elevations that have been characterized as 'illiterate neo-Georgian'. (fn. 78)

Easton Street

Easton Street was first built up in 1818–20. From the first the east side was occupied by a number of commercial premises. At the south end No. 38 is the last survivor of a row of fourteen 15ft-front houses of 1818–19 built under a lease to George Goodwin. (fn. 79) It incorporates a late nineteenth-century iron shopfront made to a patent design by F. J. Chambers (see page 123).

By the 1860s a public house called the Queen's Head stood near the north end at No. 23. In 1925–6, with rebuilding along the rest of the street pending, the brewers Mann, Crossman & Paulin built a new and larger Queen's Head to the north, on the corner of Attneave Street, now No. 22, The Easton. This was designed by William Stewart, the Whitechapel-based architect who acted for these brewers elsewhere, and built by A. E. Symes. With its distinctive corner oriel window, it survives little-altered (Ill. 335). (fn. 80)

At Nos 23 and 24 is a plain four-storey building of 1929, built for and by Philip Class of the Pentonville builder-developers A. Class & Son, to designs by Herbert A. Wright, architect. It was long occupied by tailors and children's clothing manufacturers. (fn. 81)

334. Nos 1–7 Easton Street (now Peter Benenson House) in 2006. Culpin & Son, architects, 1937–8

Nos 25–27 were rebuilt in 1923 as a two-storey metalspinning factory for Thomas Warwick & Son, with S. B. Caulfield as architect. It was raised in height in 1939, again by Caulfield for Warwicks. The building has been converted for occupation by Amnesty International. (fn. 82)

The long, three-storey range at Nos 28–37 was built in 1925–6 as a garage and engineering workshops for Babcock & Wilcox Ltd, boiler makers, with Victor Wilkins as architect and Killby & Gayford Ltd as builders. It has a reinforced-concrete frame. By 1934 the upper storeys had been let to a firm of razor-blade manufacturers. The building was taken over by Coates Brothers & Co. of Nos 1–7 opposite in the 1950s, and in 1966 a top-storey footbridge was built across the street to link to their main building. In 1982–3, after the departure of Coates Bros, the bridge was taken down as part of a conversion to office use, only to be replaced in 1987–8 when Amnesty International moved in, reunifying the two buildings. This one has since been refenestrated. (fn. 83)

No. 1, Peter Benenson House

Following redevelopment of the east side of Easton Street in the 1920s nearly all that remained opposite, Nos 4–21 as well as Easton Place, was replaced in 1937–8 in a speculation by John Laing & Son Ltd, acting as both developers and builders, with designs by Clifford Culpin of Culpin & Son, architects, and steelwork made and erected by Dorman Long & Co. Ltd. Laing and Culpin were also working together elsewhere on the Northampton Estate in 1937, on Agdon Street. Occupation by Coates Brothers as a printing-ink factory and company headquarters was agreed before the three-storey building was complete. Coates Brothers supplied ink to the Temple Press near by, and the two firms' interdependent buildings both stopped production in 1981–2.

335. The Easton, No. 22 Easton Street, in 2006

336. Cottages of c. 1830 in St Helena Place (on the Lloyd Baker estate, behind the houses in Lloyd Square), 1912. Demolished

337. Nos 1–7 William Street, of c. 1820 (now east side of Naoroji Street). Demolished

On Easton Street, continuous windows give the building clean horizontality, punctuated by vertical openings for entrances and staircases in the central and end bays (Ill. 334). Culpin had been particularly attracted, like others at this time, to the Dutch Modernism of Willem Dudok, whose Hilversum Town Hall he had visited before designing Greenwich Town Hall in 1935. The dark tiling of the lowest storey has recently been painted, but the entrances retain attractive Art Deco detail. The plans provided for a fourth storey, added in 1951–3, again under Culpin. (fn. 84)

The building was converted in 1982–3, by Kasabov Associates, architects, as offices for Amnesty International's International Secretariat. It has been renamed Peter Benenson House in honour of the humanrights organization's founder. (fn. 85)

Attneave Street

Most of Attneave Street is lined with public housing of the 1970s. Nos 16–23 and 4–15, on either side of the road, and Nos 1–27 Sherston Court to the north-west, together comprise a phased Islington Council development, completed with the southern block in 1975–7. The buildings were designed by Andrews Sherlock & Partners, and built by E. J. Lacy & Co. Ltd. These four-storey blocks, one of flats and two of maisonettes, are faced in stock brick with the upper floors in slated mansard attics. There are balconies at the rear. The west end of the road was closed with landscaping of the area between the blocks nearest Farringdon Road. (fn. 86)

Margery Street, South side

The section of Margaret Street immediately north of Wilmington Square, originally to have been part of the square itself, was not built up until 1828–30. The fifteen houses here (Nos 54–68) were the last early nineteenth-century terrace to survive in the street. Following plans for Finsbury Council, prepared by George Hebson in 1963, the site was redeveloped in 1967–8 by Islington Council as No. 65, William Martin Court. This was to provide a home for elderly people with thirty-two bedsitting rooms above common spaces. The long and plain three-storey brick range is named after Alderman Martin, a central figure in the building of the Margery Street Estate across the road (see below). (fn. 87)

Houses of around 1820 along the south side of Margaret Street at its west end were replaced in 1922 by the West Central Garage, a two-storey motor garage and filling station, designed by Boreham & Gladding, architects. By the 1960s this had come to be used as offices, and in 1972–3 it was substantially rebuilt as such for Silverstone Land Holdings, with Raymond J. Cecil & Partners as architects, and J. Jarvis & Sons Ltd as builders. The partly tile-faced block at Nos 69–84 was initially occupied by Islington Council's Architect's Department and called Gloucester House. In 1985 it became the headquarters of the Children's Society, and has been renamed Edward Rudolf House, after the Society's founder. (fn. 88)

North of Margery Street

The area immediately north of Margery Street was densely built up in the early 1820s under John Wilson as part of his commitment to the development of Spa Fields for the Northampton Estate. The estate's northern boundary ran along St Helena Place and Spring Street, a line now largely effaced within the Margery Street Estate. South of this were laid out Wilmington Place and Noble Street, which have disappeared, and Ann and William Streets, which survive as Fernsbury and Naoroji Streets. Early development along the north side of St Helena Place and facing (Lloyd) Baker Street was undertaken by the Lloyd Baker Estate around 1830 (see Chapter XI). The houses here, all now demolished, were of two storeys and generally small. Although closely packed, many were not of the meanest types, some having basements, and others double fronts (Ills 336, 337). Artisan occupancy was usual, with a great mix of trades, including diverse and specialized domestic working and some stretches of shops. The smaller houses in the courts probably housed poorer tradespeople and labourers, and they were soon subdivided. Already in 1864 there were concerns about sanitation in some of the smaller streets. New and poorer residents arrived, in large measure those displaced by clearances and road improvements elsewhere. (fn. 89)

Classic slum conditions developed, a family to a room being common, as at No. 1 Wilmington Place, where in the early 1880s there were seven families in seven rooms, and No. 15 St Helena Place, where twenty-one people in six families occupied six rooms. Some of the worst conditions were in the courts where each cottage comprised two rooms of only 9ft by 8ft, as at Bolton and Margaret Courts (formerly Places); Bolton Court's five two-room properties housed 34 people. (fn. 90) In The Nether World (1889) George Gissing placed Bob Hewett, a coin counterfeiter, in one of the small houses of Merlin's Place where, in 1891, the real No. 2 had eighteen people in three households. Booth's investigators recorded in 1898 that St Helena Place was populated by 'rough women wearing sack cloth instead of stuff skirts', and that Wilmington Place was 'noted for pistol gangs'. (fn. 91)

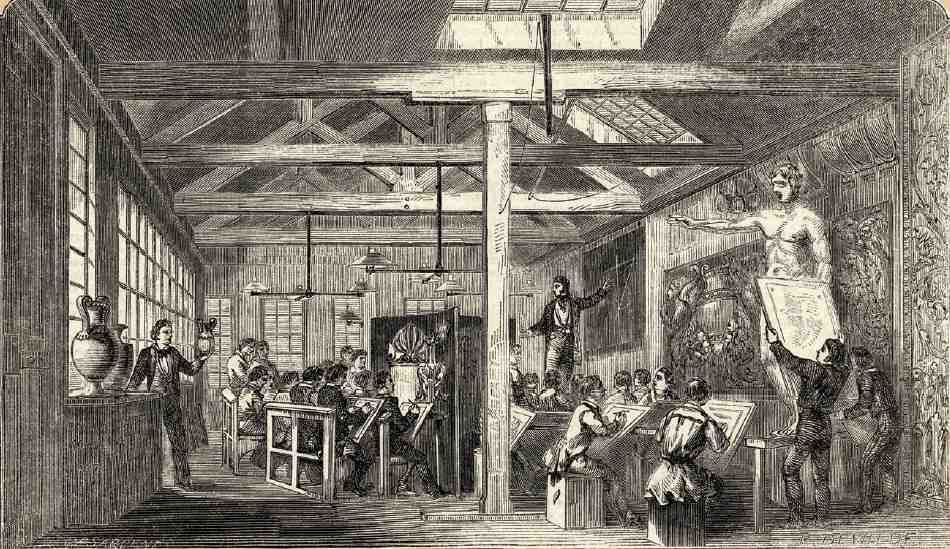

338. The Finsbury School of Art, c. 1850. Demolished

Not all was grim. In the 1850s and 60s neighbouring buildings in William (now Naoroji) Street housed a private school of art and a church school. The status and operating period of the school of art, always small, are obscure. Occupying the width of two houses and probably reaching through to Ann Street behind, it seems to have started out as the 'Wilmington Square Schools of Design' (Ill. 338), but by 1860 was known as the Finsbury School of Art. Probably it originated in the movement at this time for schools of design connected with trades. In the late 1850s Frederick Goulding, the printer of etchings, was a student, and Kate Greenaway took her first lessons in drawing here, aged about eleven. The Finsbury School of Art seems not to be identifiable with the school at Canonbury House, Islington, at which Kate Greenaway took later lessons. It was hoping for purpose-built premises in 1862, but disappeared from William Street about 1865. (fn. 92) Immediately north of the school of art, St Mark's Church Sunday School occupied a building at the corner with St Helena Place until about 1862, when St Philip's National School took it over. When the school of art left or closed, St Philip's seems to have annexed its premises for its infant department. The school's quarters were regarded as temporary in 1871, and in 1876 it moved to a permanent new building in Gwynne Place (see page 314). (fn. 93) The William Street buildings were replaced in the 1880s by the extension of the School Board's Ann Street School to the south (see No. 1 Naoroji Street below). Most of the rest of the area was transformed as the Margaret Street Estate following clearance in the 1920s; Margaret Street became Margery Street in 1937.

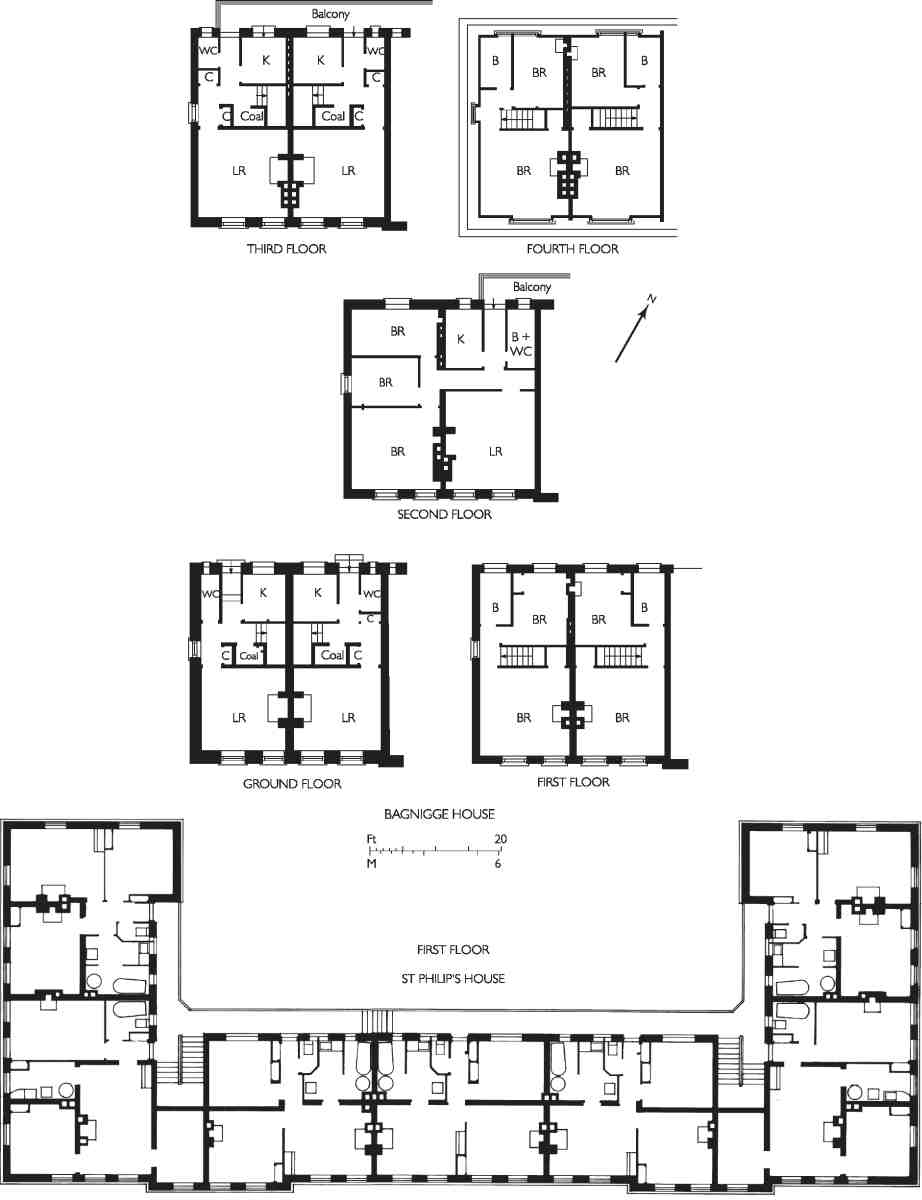

Margery Street Estate

The Margery Street Estate, built in two phases between 1930 and 1933, was the most ambitious housing scheme undertaken by Finsbury Borough Council before the war (Ills 339–43). Originally comprising 250 flats and maisonettes in nine blocks, it was intended as a showpiece by Finsbury's first Labour Council, elected in 1928, and herald of great things to come. That was not to be, though in 1947 Harold Clunn judged these to be 'very superior blocks of workers' flats, with spacious courtyards at the back … some of the finest of their kind in London'. (fn. 94)

The three-acre site, bounded by Margaret Street, Fernsbury Street and Lloyd Baker Street, had been acquired by the Post Office in 1921 for the building of staff offices, and largely cleared. In the late 1920s there remained only about sixty houses and shops on Margaret and Lloyd Baker Streets. With such relatively minor rehousing implications the Medical Officer of Health, A. E. Thomas, in a comprehensive report of 1929 on Finsbury's 'housing question', recommended the site for new housing and after protracted negotiations it was acquired in July 1930. (fn. 95)

E. C. P. Monson, the architect of two earlier and smaller developments for the council in Pentonville (Grimaldi House and Mandeville Houses), had already prepared plans, applying substantially higher space allowances than in those buildings or in his previous work for Islington Council. His scheme for nine blocks of six storeys to provide 74 flats and 197 maisonettes was unusual in having such a high proportion of maisonettes. The term had only recently been applied to two-storey flats in blocks as opposed to flats in divided terrace houses, with the London County Council's provision in the early 1920s of 'twostorey lettings' or 'maisonettes' at the top of tenement blocks, dormered attics providing a bedroom storey. Most such blocks were not in areas as densely populated as Finsbury, and blocks of more than three storeys with lower-storey maisonettes were rare. The height of these buildings allowed for three-quarters of the site to be used as gardens, playgrounds and drying areas, while permitting the overall density to remain high, at 85 dwellings an acre. (fn. 96)

339. Spring House, Margery Street Estate, during construction. E. C. P. Monson, architect, for Finsbury Borough Council, 1930–2

340. Greenaway House, Margery Street Estate, following completion in 1932

Following representations from the Ministry of Health, a revised scheme at reduced density but still providing maisonettes, gardens and drying areas, was approved by the Housing Committee in February 1930. Construction was phased to allow displaced private tenants to be rehoused at once. It began in November 1930 and the foundation stone was laid by William Martin, mayor of Finsbury and chairman of the Special Housing Committee. The first six blocks, Bagnigge, St Ann's, Spring, St Helena, Earlom and Greenaway Houses were completed in 1931 and 1932, providing 46 flats and 87 maisonettes (Ills 339–40, 342–3). (fn. 97) They were built by direct labour (despite opposition from Tory councillors), and it was boasted that Finsbury men had been employed in all trades; one of Labour's electoral pledges had been 'Work for Finsbury men'. (fn. 98) The names derived from local streets, landmarks, and people associated with the area: Kate Greenaway, the children's book illustrator, had attended the Finsbury School of Art in what is now Fernsbury Street, and Richard Earlom, the mezzotint engraver, had lived nearby.

Along Margery Street the central block, Spring House, is set back on an axis that gives a palatial prospect down Yardley Street, with a grandly architectural entrance behind a landscaped rose-garden forecourt. It is flanked by four blocks, St Ann's House and Bagnigge House to the west, and St Helena House and Earlom House to the east. Greenaway House faces Fernsbury Street.

The blocks are of five and six storeys, with flats sandwiched between tiers of maisonettes. They have internal staircases and open balconies, but no lifts. Red brick and sash windows were used for the street frontages with plain stock brick and steel casements for the more utilitarian balconied rear elevations. Classical and Egyptianizing artificial-stone dressings enliven otherwise undemonstrative neo-Georgian exteriors: the idealism was to do with housing provision, not architectural style. (fn. 99)

The internal layout of the flats provided for separate bathrooms and scullery-kitchens, which were supplied with gas, electricity and hot water (Ill. 342). An obvious advantage of the lower-level maisonettes was privacy, as it was not necessary to place bedrooms and bathrooms on the same floor as access balconies. (fn. 100) The rents, set at about 4s per room, were high, almost double those for rooms in private multi-occupied houses, but the council hoped to encourage large families to move in through the introduction of a children's allowance of 6d per week. (fn. 101)

341. Riceyman House, Margery Street Estate, in 2006

342. Bagnigge House, Margery Street Estate (top). Plans of all floors at one end of the block as designed in 1931, with three-bedroom flats between two tiers of two-bedroom maisonettes. St Philip House, Margery Street Estate (below). First-floor plan as designed in 1932

343. Earlom House, Margery Street Estate, in 2006

Finsbury's project failed to qualify for the hoped-for slum-clearance subsidies, and about £30,000 was spent in excess of loan sanction, which did not escape the notice of the District Auditor. When the northern part of the development was begun in 1932, under a new Conservative administration, it was impossible to carry on such high standards. Monson, in collaboration with the borough engineer, A. V. Cole (who had been brought in to reduce costs), and after some upset, proposed three blocks containing 115 mostly two-bedroom flats. This went ahead following uproar in the council chamber and despite an attempted rearguard action by the Lloyd Baker Estate, belatedly concerned 'to preserve the architectural unity of Lloyd Square'. Gee, Walker & Slater Ltd, the lowest tenderers, were taken on as builders for this more economic scheme, which was completed in 1933. (fn. 102)

The three blocks, Riceyman, St Philip and Gwynne Houses, are named after more local landmarks and associations: Arnold Bennett's Clerkenwell novel of a few years before, Riceyman Steps; St Philip's Church in Granville Square; and Nell Gwynne, who may have lived nearby at Bagnigge House in St Pancras. They are of five and six storeys and, as built, comprised 28 three-bedroom and 91 two-bedroom flats. The architectural treatment is similar to the earlier blocks, but simpler and cheaper (Ill. 341). Externally, dressings are no more than 'snowcrete'-rendered concrete bands and cornices. Internally, flats were fitted with a gas copper but no gas cooker, a coal fire in the living room and a gas fire in one bedroom. The sunken St Helena Garden, to the east of St Philip House, was a late addition, in place of an intended extension of Fernsbury Street through to Lloyd Baker Street. (fn. 103)

At the west end of the estate is Charles Simmons House, designed in 1963 by the borough engineer, George Hebson, and named after a prominent member of the Housing Committee. It is a low-rise four-storey block of sixteen one-bedroom balcony-access flats, built of reinforced concrete faced in stock brick. To its rear along Lloyd Baker Street there is a community hall, formed in 1982–3 from what had been garages and children's play space. (fn. 104)

No. 1 Naoroji Street

This much-remodelled building is a peculiarity, an early conversion of a board school to office use. It originated as Ann Street School, and was built in two phases (Ill. 344). The first, in 1876–7, comprised the southern half of the building and was designed by the London School Board's architect, E. R. Robson, to provide for 572 pupils. The contractor was B. E. Nightingale, who subsequently added the school-keeper's house to the north on Ann Street. (fn. 105) Robson's successor, T. J. Bailey, extended the school in 1884–5 for another 585 children, over the site of the former School of Art that had been adapted for St Philip's National School (see above). John Grover was the contractor. (fn. 106) It became Fernsbury Street School following the renaming of Ann Street in 1912, the new name being an archaic spelling of Finsbury.

Following the school's closure in 1915 the building was promptly taken over for the administration of the recently instituted national insurance scheme, as the offices of the Insurance Committee for the County of London. William Street alongside was renamed Insurance Street in 1916. Insurance House, as it became, was completely remodelled to provide better office accommodation in 1938–9, with George Leonard Russell as architect, and Holland, Hannen & Cubitts as contractors. The School Board's characteristic gables were removed or cut down, and the building was clad in faience and rendered on the Insurance Street front, which had been the back of the school (Ill. 345). Some windows were enlarged, and the interior was substantially reconstructed. (fn. 107)

344. Fernsbury Street School (now No. 1 Naoroji Street) in 1938, showing block of 1876–7 to left (E. R. Robson, architect) beyond extension of 1884–5 (T. J. Bailey, architect)

345. Insurance House (now No. 1 Naoroji Street) in 1939, showing the refacing of 1938–9

After the war, when a two-storey reinforced-concrete wing was added to the south-west, the building was occupied by the London Executive Council of the new National Health Service. It remained in public-sector occupation until 1999, latterly as the offices of the Camden and Islington Community Health Services Trust. It was then sold off, and since 2001 has been occupied by Oyster Partners Ltd, internet and media consultancy. (fn. 108) Insurance Street became Naoroji Street in 1992, after Dadabhai Naoroji, who became Britain's first Indian Member of Parliament (for Finsbury) in 1892. (fn. 109)

Other Buildings

New Merlin's Cave (demolished)

The New Merlin's Cave public house of 1921–2 was the

successor to two earlier Merlin's Caves (see above), but on

a new site, previously occupied by 1820s houses, at Nos

34–39 Margaret Street. The move was occasioned by plans

for the obliteration of Merlin's Place. The new pub, with

a recreation or public room at the back, was built for

Barclay Perkins & Co., to designs by that firm's architect,

F. G. Newnham. The contractors were Thomas & Edge of

Woolwich. Another room, for dance or concert use, was

added to the rear in 1924–5. The public house was run as

a family café, one of two built by Barclays as an experiment. A response to the influence of temperance campaigners and perceived social changes, these were

cafés of the Continental kind, without bars or obscured

windows. They serve lunch, tea, dinner, and supper in the

restaurant, and drinks in the buffet; and another department