Pages 5-21

Whitehall: Historical and Architectural Notes. Originally published by Seely, London, 1895.

This free content was digitised by double-rekeying and sponsored by donations to BHO's digitisation fund. Public Domain.

CHAPTER I

Site of Whitehall in the Twelfth Century—Part of Westminster—Hubert de Burgh—|York House—Wolsey—Hentzner—Henry VIII.—His Honour of Westminster—Holbein's Gate—Anne of Cleves—Funeral of Henry VIII.

When Abbot Laurence, of Westminster, looked out to the northward or north-eastward, he could see no land—as far as the wall of London—which did not belong to him and his house. This was the Abbot who first had leave to assume the mitre, and in 1163 he obtained from Pope Alexander II. the canonisation of Edward the Confessor. When worshippers wished to kneel at the new saint's shrine they had to reach Westminster as best they could. Some, especially those who lived at Charing, or further up the hill, in what was afterwards Hedge Lane, would make their way to the Thames, the best highway in those days. In some seasons, perhaps, the water-courses, which had their origin in the Tyburn, might be dry enough to let them pass, but there were as yet no regular roads and no bridges. One of these water-courses supplied the Abbey, and one ran out where Richmond Terrace is now. We have two documents from which to draw a picture of the ground which was not yet Whitehall. First, we have the evidence afforded by the geographical features of the locality; and, secondly, we have the report of a trial which took place some sixty years ago, when, no doubt, all possible charters and grants and leases and demises were cited. The trial was between the people of Westminster and the people who lived in Richmond Terrace. Westminster claimed that the Terrace was within the boundaries of St. Margaret. The Terrace claimed that it was extra-parochial, as being on part of the site of the palace of Whitehall. The counsel for Westminster was able to show that Whitehall had been private property before the reign of Henry VIII., and that neither he nor any one else had made it extra-parochial. The verdict, therefore, was in favour of the parishioners of St. Margaret.

We may return to this interesting and instructive report, with its wealth of ancient evidence, and interrogate that much more ancient document, the face of the country. Strange to say, a great deal of that country remains as it was in, say, the reign of Henry III. The green fields and the water-courses are there, though the Abbot in 1250 could no longer look across his own land all the way from Westminster. The divided Tyburn wandered over the green expanse, untroubled with bridges. Two or three small brooks formed here a kind of delta. On the south, one of them ran through Westminster Abbey and divided Thorney Island from Tot Hill. Another ran through the district we call Whitehall. The land between was low and marshy, and even at the present day, when there has been so much levelling up, the statue of Charles I. is upon ground ten feet higher than Parliament Street. If, standing on the future site of Whitehall we looked to the westward, we saw nothing but a vast tract of low green meadow-land. If we looked to the south, we might have seen the new buildings of Westminster Abbey, unless when the Danes had been on the warpath. If we looked to the eastward, we found that the Thames washed up close to our feet.

At this early period, and down to the reign of King Edward I., there were no houses in sight, except those which clustered about the Abbey, those which constituted the village of Charing, and in the far distance the grim walls, the red-tiled roofs, and the church towers of the City. London was more plainly visible than it is now, and on account of a curious bend in the course of the Thames, was nearly as visible from Westminster. By the thirteenth century a great change had come over all the district. The Thames was better confined within its proper limits; some measure of embanking had been carried out, and a great many alterations in City life, in Church arrangements, and in the King's policy have been detailed in the histories of London. We need not go far into them here. Before 1200, all the land between the Abbot and London belonged to him. By 1222 all was changed, or about to be changed, and the Abbot owned nothing except the advowson of the far-off St. Bride's. St. Bride's belongs to Westminster even now. The King laid claim to certain foreshores on the banks of the Thames. Undoubtedly, they belonged by an ancient grant to the Abbot, but we must take into consideration that what had been only occasionally dry land in the eleventh century was permanently dry in the thirteenth; and the King had conferred, and was conferring, too many benefits on the Abbot and his monks and their church to permit them to dispute his royal, if illegal, pleasure. The Bishop of Exeter formed a little estate of the Outer Temple. From his precincts westward the constant embanking, and especially the formation of the roadway of the Strand, left a wide strip now permanently dry. This strip the King erected into a manor, and bestowed upon his wife's uncle, Count Peter. Peter became Count of Savoy in 1263, and the manor has ever since been called after him. The next of these reclamations was Whitehall. In the lawsuit already mentioned, a document was produced which threw great light on the early history of the district. It relates to the sale by Roger de Ware and Maud, his mother, to Hubert de Burgh, of their land here. Another document was a similar sale by Odo, the King's goldsmith, of an adjoining plot, identified as stretching from the highway to the Thames.

Hubert's choice of a residence was determined, no doubt, because it placed him within easy reach of the city on one side, and of the King's palace on the other. He probably seldom used the road through the newly-constructed King Street, or the other road through the Strand—a road famous for ruts and mud. He went either to Westminster or to London by water, as did his great neighbours in the Savoy, and the bishops who had palaces outside the Bar of the Temple. We often wonder why our ancestors preferred these low-lying places for their houses. The answer is the difficulty they experienced in locomotion by land. The "silent highway" of the Thames was such a convenience that all who could possibly afford it preferred to be within easy reach of water.

Hubert had no easy part to play. From 1227 he had to do daily battle with the young King, who already, though still a boy, showed signs of the combined obstinacy and incompetence which characterised him through life. Hubert saw the impolicy of yielding to the papal claims. He followed, as Bishop Stubbs remarks, in the footsteps of William Marshall, taking a middle path between the feudal designs of the great nobles and the despotic theories of the late King. In both these particulars he was in opposition to Henry, who was bound to the Pope by his education, and to the retrograde party by his personal prejudices. Hubert served the King too well to please the people, and spared the people too much to satisfy Henry. In 1232 he was dismissed, and his ungrateful master, not content with his dismissal, trumped up a series of charges against him, just as Henry's descendant, Henry VIII., did with regard to Cardinal Wolsey. Hubert had been made Earl of Kent in 1227, and Constable of the Tower of London just before his disgrace—in fact, only a few days before—and during the same month was himself lodged in the Tower as a prisoner. Eventually his lands were restored, but he was not allowed to leave his castle at Devizes; he survived till 1243, when he died, as Matthew Paris relates, "full of days." He had been five times married, and reckoned among his wives the widow of King John, and the sister of Alexander III., king of Scotland; but he left only two children, John, his son, and Margaret, his daughter. The subsequent history of the land now called Whitehall, so far as Hubert was interested in it, may be briefly detailed. Hubert had made a vow to go to the Holy Land and fight the infidel, being himself, as Roger of Wendover says, Miles strenuus; but not being able to fulfil his vow, he gave his land at Whitehall, which he describes as being in the parish of St. Margaret's, into the hands of trustees to be sold in aid of an expedition to the Holy Land. The trustees promptly sold it to Walter Grey, archbishop of York, who annexed it to his See. Walter died in 1255, and was succeeded by Sewall Bovill, who had been Dean of York. Thirty archbishops in all held this house, beginning with Walter Grey and ending with Thomas Wolsey. It is curious to remark that no trace now exists of their occasional residence. It was uniformly called York House, and we may be sure that Wolsey improved it, and built a hall and a chapel similar to those at Hampton Court. One or two old views show us stately and lofty buildings in the half-Gothic, half-Italian style, which is so familiar at Christ Church at Oxford, and at King's College at Cambridge. A large hall was in King Street; that is, outside Holbein's Gate. We see it beyond the gate in Silvestre's view; and it stands up dark and heavy, with its strong buttresses on the left hand, in T. Sandby's view. In the last century, when it had been part of the Treasury buildings for generations, it was newly fronted in stone, and the buttresses turned into pilasters. Since then it has been refronted twice—by Soane in 1824, and by Barry in 1846. Barry greatly increased the length. It would be interesting, but almost impossible, to ascertain if any of the masonry of Wolsey's building still remains within the new walls.

This is, of course, a digression. No part of the Treasury is in Whitehall; but the reason for mentioning it is that its inclusion in the two engravings I have named shows us what, in all probability, Wolsey's other buildings were like. Paul Hentzner, writing in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, says that they were "truly royal." Very little building of any importance went on under Henry VIII. or his three immediate successors, so that Hentzner's allusion must be to what Wolsey left. It is true, as we shall see, that Henry proposed to improve and extend it; but we may rest certain that he added nothing to its magnificence, if we except the gates; as the anonymous author of Dodsley remarks, he had a greater taste for pleasure than for elegance of building, and immediately on entering upon possession he ordered a tennis court, a cockpit, and a series of bowling-greens.

But we are going too fast. In the beginning of 1530 Cardinal Wolsey was still in possession, and there are various accounts of how he transferred the palace of his predecessors to the King. Henry was not very scrupulous in matters of this kind. He was much given to breaking the tenth commandment, and especially to coveting his neighbour's house. He had already helped himself to Hampton Court, and a curious anecdote will be found in Thorne's Environs. Lord Windsor was much attached to his place at Stanwell, which had descended to him from a long line of ancestors. The house, no doubt, was in what agents nowadays call ornamental repair. He entertained the King royally, and Henry, with the kind of gratitude peculiar to him, promptly commanded him to hand it over. He gave in exchange the Manor of Bordesley and the Abbey, which Henry had taken from the monks. Windsor had just laid in a stock of provisions for his Christmas festivities, but he refused to remove them, saying that the King should not find it bare Stanwell when he came to take possession. The curious part of the story is that Henry does not seem ever to have visited it again, and we know that he soon afterwards leased it away. At the time of Wolsey's fall, Henry had been for several years almost without a home in London; his apartments at Westminster were burnt in 1512, and after twenty years, in 1532, he bought the hospital of St. James's-in-the-Fields. Between these dates he would have been without a London palace, except the Tower or Bridewell, but on the fall of Cardinal Wolsey certain illegal formalities were complied with, and Henry became possessed of Whitehall. The gates north and south of the royal precincts were needful on account of the old right of way between Charing—now become Charing Cross— and Westminster; and in 1535 Henry built the church of St. Martin, near to where the royal mews had been from time immemorial, with a view to prevent the constant passage of funerals from the northern to the southern part of St. Margaret's.

In addition, Henry acquired all the land between Charing Cross and an outlying suburb of Westminster known as Little Cales, or Calais. More than this, he annexed all the green to the westward, which I have already mentioned. Abbot Islip had, in fact, nothing left of the great manor which after the Conquest had belonged to Westminster Abbey. The City of London had acquired the great ward of Farringdon Without. The lawyers had the Inner and Middle Temples. The King had inherited from the wife of John of Gaunt all the manor of the Savoy. And now Henry VIII. helped himself to the remainder.

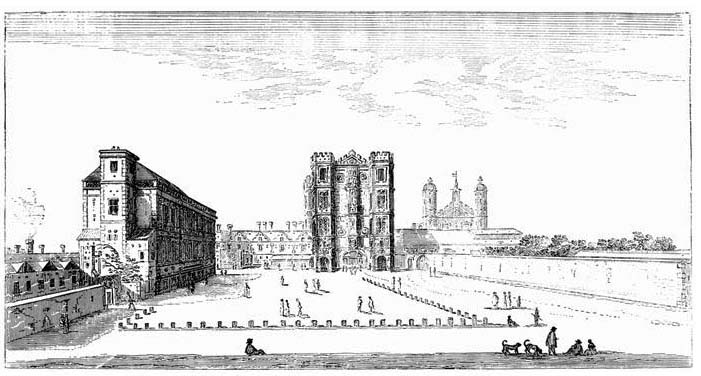

Banqueting Hall, Holbein's Gate, and Treasury. From the Engraving by J. Silvestre, 1640.

It will be interesting to see the document by which the Abbot conveyed the inheritance of his house to the King. I am tempted to quote it nearly whole, but recommend the reader who is not interested in such things to skip on. No more quotations of the kind occur in this little book, but some readers may find the numerous landmarks enumerated worth making a note of, as most of them have long been obliterated:—

"To all Christ's faithful people to whom this present writing indented shall come: John Aslyp, abbot of the monastery of St. Peter, Westminster, and the Prior and Convent of the same monastery, Greeting in the Lord everlasting: Know ye that we, the aforesaid Abbot, Prior, and Convent, with the unanimous assent, consent, and will of our whole Chapter, in our full Chapter assembled, have given, granted, and by this our present charter indented, confirmed to Sir Robert Norwich, Knight, our Lord the King's Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Sir Richard Lyster, Knight, Chief Baron of the Exchequer, Sir William Pawlett, Knight, Thomas Audeley, serjeant-at-law of the Lord the King, and Baldwin Malet, solicitor of the Lord the King: a certain great messuage or tenement commonly called Pety Caley's, and all messuages, houses, barns, stables, dove-houses, orchards, gardens, ponds, fisheries, waters, ditches, lands, meadows, and pastures, with all and singular their appurtenances in any manner belonging to the said great messuage or tenement called Pety Calais, or to the same messuage adjoining, or with the same messuage heretofore to farm, let, or occupied; situate, lying, and being within the said town of Westminster, in the county of Middlesex. And also all those messuages, cottages, tenements, and gardens situate, lying, and being on the east side of the street, commonly called the Kynge's Strete, within the said town of Westminster, in the aforesaid county of Middlesex, extending from a certain alley or lane, there called Lamb Alley, otherwise called Lamb Lane, unto the bars situate in the aforesaid Kings Street, near the manor of the Lord the King there, called York Place. And also all other messuages, cottages, tenements, gardens, lands, and water, late in the tenure of John Henburye, situate, lying, and being on the said east side of the highway aforesaid, leading from a certain croft or piece of land commonly called Scotlande, to the Chapel of St. Mary de Rouncedevall, near the cross called Charyng Crosse. And also all those messuages, cottages, tenements, gardens, lands, and wastes, lying and being on the west side of the aforesaid street, called the Kynges Strete, extending from a certain great messuage or brewhouse, commonly called the Axe, along the aforesaid west side, unto and beyond the said cross called Charyng Crosse. And also all other lands, tenements, and wastes, lying on the south side of the highway leading from the aforesaid cross called Charyng Crosse, unto the hospital of St. James in the Field. And also all those other lands and meadows lying near and between lands lately belonging to the aforesaid hospital of St. James on the south side of the said hospital, and so from the aforesaid hospital on the south side of the highway extending towards the west unto the cross called Cycrosse, and turning from the same cross extending towards the south by the highway leading towards the town of Westminster, unto the stone bridge called Eybridge, and from thence along the aforesaid highway leading towards and to the aforesaid town of Westminster, unto the south side of the land there called Rosamundis, and so from thence along the aforesaid south part of the aforesaid land called Rosamundis, towards the east, directly unto the land, late parcel of the aforesaid great messuage or tenement called Pety Calais, and to the same great messuage or tenement belonging, containing in the whole by estimation, eighty acres of land more or less, and one close late in the tenure of John Pomfrett, now deceased, containing by estimation twenty-two acres of land, lying in the parish of St. Margaret's, Westminster, in the aforesaid county of Middlesex, except always and so as the aforesaid Abbot, Prior, and Convent, our successors and assigns, wholly reserved as well as the aqueduct coming and running to our aforesaid monastery."

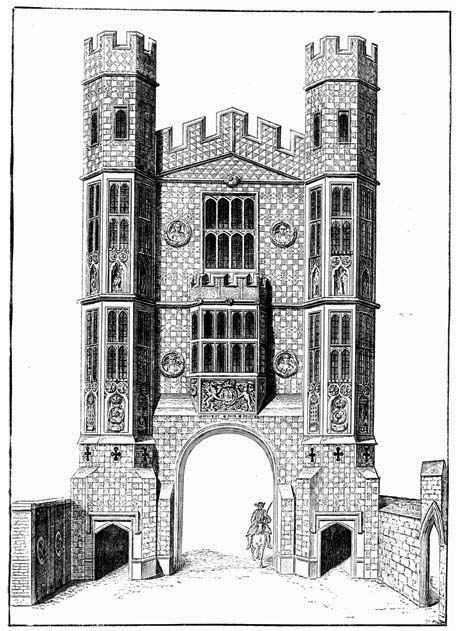

Holbein's Gate. From the Engraving by G. Vertue, 1725.

Had Henry foreseen the course which his policy of confiscation would lead him into, he might have waited till 1539, when all the monastic estates became his. However, there is much to interest us is this strange document. We see that when Henry had annexed Whitehall to Westminster in such a way as to call the two by the same name—that is, "our palace of Westminster;" and when he had annexed the whole expanse of St. James's Park to both, and had made of St. James's a kind of lodge to Whitehall—when from St. James's he could look up the green hills towards Hyde Park, which he had also taken from the Abbot of Westminster, and beyond that again towards Hampstead Hill—the intervening country being all open and void—he took special leave from a subservient Parliament to make the whole into "an honour." "Forasmuch as the King's most royal Majesty is most desirous to have the games of hare, partridge, pheasant, and heron preserved in and about his honour at his palace of Westminster, for his own disport and pastime to St. Giles's in the Fields, to our Lady of the Oak, to Highgate; to Hornsey Park; to Hampstead Heath; and from thence to his said palace of Westminster, to be preserved and kept for his own disport, pleasure and recreation; his highness therefore straightly chargeth and commandeth all and singular his subjects, of what estate, degree or condition soever they be, that they, nor any of them, do presume or attempt to hunt, or to hawk, or in any means to take, or kill, any of the said games, within the precincts aforsaid, as they tender his favour and will eschew the imprisonment of their bodies, and further punishment, at his Majesties will and pleasure."

Henry spent considerable sums of money in making an orchard, probably where the so-called Whitehall Gardens are now. Two thousand five hundred loads of stone were used in this work and in enclosing St. James's Park. But the only additions to Wolsey's building seem to have been a long gallery which ran northward towards Charing Cross; there was also a passage, but of what kind we do not know, "through a certain ground named Scotland."

There are numerous engravings extant of the northern gateway. It was in the most florid taste of the day. Perhaps we can best realise its appearance by a visit to Hampton Court. The great gate there is made of ornamental brickwork and decorated with terracotta statues or busts. Thomas Sandby's drawing shows the view from King Street very well. On our left are the buildings of the Treasury. To the right beyond the gate is the Banqueting House. Apparently when this view was taken the gate had become wholly detached from what remained of the palace after the fire of 1697. Wilkinson's view (I. 143), from a drawing by Hollar, taken in the early part of the reign of Charles I., shows a line of four gables connecting the gate and the Banqueting House, and we know that a gallery or passage led from the park, through the first floor of the gate to the palace. By this circuitous route it was that Charles reached the place of his death. In Hollar's view the arch of the gate contains a flat ceiling and a window, which greatly spoils its appearance. At the park end of the passage there was a staircase. Adjoining this end of the passage, and very near where Downing Street stands now, was a tilt-yard, and close to it a small barrack for the Foot Guards. Beyond it, further to the north, was the yard of the Horse Guards, very much as it is still. Behind the spot where James I. built the Banqueting House, to the eastward, was the court, a very irregular space, divided by a passage passing over an archway. This passage led to the great hall and the chapel, which last was close to the river's bank. The King's lodgings also looked on the Thames, but between them and the chapel there was a labyrinth of small chambers and sets of chambers. To the westward of these small and inconvenient apartments, some of which were appropriated for the Queen and her maids of honour, was the great Stone Gallery, which looked on the garden and the bowling-green. How far these arrangements were due to Cardinal Wolsey and how far to Henry VIII. we cannot say. Undoubtedly, the whole palace was most inconvenient, even at that day, when men's ideas of comfort were so different from ours. There was not, if we except the so-called Great Hall, a very small building compared with that of Hampton Court, a single large or handsome chamber in the whole place. Room was, however, found for a library, and Paul Hentzner mentions it with praise. In it he saw a book in French written by the Princess, afterwards Queen, Elizabeth, with her own hand, and inscribed to her father: Elizabeth sa très humble fille rend salut et obédience. "All these books," continues Hentzner, "are bound in velvet of different colours, though chiefly red, with clasps of gold and silver; some have pearls and precious stones set in their bindings." There are probably a few representatives of this library among the books which belonged to Henry VIII., and have his name or arms, in the British Museum. Hentzner also notices the furniture of inlaid woods, some stained glass representing the Passion, and a gallery of portraits and other pictures. He visited Whitehall in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, when the place must have been very much as it was left by Henry VIII. He mentions, among other things, the Queen's bed, "ingeniously composed of woods of different colours, with quilts of silk, velvet, gold, silver, and embroidery." Among the portraits is one, the description of which puzzles me: "A picture of King Edward VI., representing at first sight something quite deformed, till by looking through a small hole in the cover, which is put over it, you see it in its true proportions." Can this have been a device of the same sort as the distorted skull in Holbein's picture of "The Ambassadors" in the National Gallery?

Whitehall, from King Street. From a Drawing by T. Sandby, R.A. Engraved by R, Godfrey, 1775.

Henry VIII. continued to date documents of all kinds at "Westminster," meaning Whitehall. It is possible that St. James's was similarly included in Westminster. In or about 1537 the King's house there was greatly improved and beautified, it is said by Cromwell, in anticipation of Henry's marriage with Anne of Cleves. The initials "H. A." on some of the fireplaces and ceilings were probably put up in allusion to the same marriage, and have nothing to do with Anne Boleyn. It was intended that Henry and Anne (of Cleves) should pass their honeymoon at this remote corner of the park as it was then, there being no buildings whatever visible from the gate. The result we all know; and Henry, long before the honeymoon had waned, was back at "Westminster." Events travelled rapidly in those days. Anne Boleyn was beheaded in May, 1536. In the same month Henry was married to Jane Seymour. She died in October, 1537. In January, 1539, Henry married Anne of Cleves, and divorced her in July. In April following Cromwell became Earl of Essex, and was beheaded in July of the same year. No doubt Whitehall was the principal scene of the long tragedy indicated by this dry list of dates. At "Westminster" Henry conferred a peerage on Cromwell's son, Gregory; and there, too, he issued letters of naturalisation to the Lady Anne of Cleves, and gave her several manors. One more tragedy and we have done with Henry VIII. On a day unknown, in January, 1547, the King lay dying at Whitehall. So weak had he become that he was obliged to leave it to others to execute his cruel and relentless orders. He died at Whitehall on the 28th, the last act of his life having been to send the poet Surrey to the scaffold, and to prepare a similar fate for Surrey's father, the Duke of Norfolk. The Duke being a peer, the process for obtaining an act of attainder was slower. A commission had been issued by the tyrant to Wriothesley, St. John, Russell, and Hertford to give the King's consent to the Bill. But death stepped in and the Duke's life was saved.

Whitehall. From an Engraving after a Drawing by Hollar in the Pepysian Library, Cambridge.

Sandford gives a very circumstantial account of the funeral ceremonies at the burial of Henry VIII. It is chiefly interesting because he names several apartments of Whitehall Palace. At first the body lay in the King's private chamber, and there received some embalming treatment, and was wrapped in lead. The chapel, the cloister, the hall, and the King's chamber were all hung with black. On the 2nd of February the coffin was taken into the chapel. We read of cloth of gold and a pall of tissue. The altar was covered with velvet, adorned with scutcheons of the Royal arms. Twelve lords, mourners, sat or knelt within the rail. Watchers likewise took turns of duty, and, as the people passed by, a herald cried to them, saying, "You shall of your charity pray for the soul of the most famous prince, King Henry VIII., our late most gracious king and master." The body was not to lie in the sumptuous but despoiled chapel Henry had raised for his father and mother. On the 14th of February the wax effigy was ready, and a procession, which Sandford says was four miles long, started for Windsor. Henry had desired to be buried beside Jane Seymour. Syon was reached the first night, and the journey was ended at one o'clock the next day.

There is nothing to connect Edward VI. with Whitehall during his short reign. But Mary, his successor, was constantly there. She is said to have preferred St. James's, and the first separate mention we have of it in a State paper is in December, 1556. She died there in November, 1558.

Elizabeth made much use of Whitehall, but her buildings and improvements at Windsor must have proved a powerful attraction. She went about a good deal, and her State papers are signed in a great variety of places. She left no mark on Whitehall, although, at the very end of her reign, instead of Henry the Eighth's "palace of Westminster," we have "Whitehall," pure and simple, one or twice. We have seen how York Place became the Palace of Westminster. How it again changed its name, and became Whitehall, we do not know. The change seems to have been made by Elizabeth shortly before her death, and the name may have already been in popular use. After her death, at Richmond, in March, 1603, her body lay in state at Whitehall, and was buried in the Chapel of Henry VII.

With the Stuarts we have a new epoch in the history of Whitehall.